Telling one’s own story is a way of asserting identity. It is simultaneously a fundamental responsibility and an inherent gift for each human being—and is often one of the first casualties of colonialism and oppression. Indigenous storytellers, knowledge holders, and practitioners who tell their own stories have long been viewed as superstitious or primitive by colonial institutions—universities, government agencies, professional associations, and so on. By stories, we mean the complex and deeply contextual oralvtraditions and narratives that involve Indigenous peoples and our place in the world. These kinds of stories embody scholarly rigor, political resistance, and moral authority. Even today, Indigenous scholars who are highly credentialed by colonial institutions are sometimes viewed as too subjective or too biased when speaking on behalf of their own people. We are two Lumbee scholars working in academia and in tribal government, and like many Lumbees, we know what it is like to have our community’s expertise dismissed and diminished on matters related to our own identity.1

Lumbees are Indigenous people of the southeastern United States whose ancestors survived the first waves of European colonization centuries ago. Our collective identity as American Indians was affirmed by the state of North Carolina in 1885, and by the United States Congress in 1956. The 1956 Lumbee Act, however, limited the formal government-to-government relationship between the United States and the tribe. Lumbee people are still working to remove the limiting language of the 1956 Act in order to achieve full federal recognition. Not only does this language impede access to certain legal, political, and cultural resources, but it also has cast a continual shadow on Lumbee identity in the eyes of individuals and groups who know nothing about us beyond the mixed message of the 1956 law.

It should go without saying, but Lumbees are experts on their own identity. Our families, elders, and tribal institutions hold much of our knowledge and expertise about who we are and where we come from. Lumbees have also participated in the creation of an extensive record of research within colonial institutions. We exert sovereignty, in part, by maintaining the integrity of oral traditions and other forms of knowledge about ourselves.

But despite being the foremost experts on our own history and culture, Lumbee perspectives often take a back seat to outsider views in academic and bureaucratic settings. Outsider views include efforts by researchers to describe, catalogue, and define us as a people—work that often ignores or misuses Lumbee knowledge about ourselves. These efforts often bend our oral traditions, documentary records, and other forms of knowledge to support racist, colonial narratives that go something like this: Indigenous peoples probably never lived in this particular place; if they did, then they left long ago; if they stayed behind, then they must have assimilated into mainstream society. The cascade of assumptions springs from the doctrine of Manifest Destiny and from other cultural beliefs that are passed from generation to generation through school curricula, holiday traditions, media, and other avenues that perpetuate racist stereotypes about who Indigenous people are, how we live (that we even live), what we ought to look like, and more. These ideas are so deeply ingrained in the public imagination that most people are unaware of the assumptions, beliefs, and stereotypes that inform their views of American Indians and our identities.2

Researchers unconsciously incorporate these racial and cultural biases into their work, leading them, for example, to be dismissive of oral tradition and traditional knowledge. In the case of Lumbees, such biases prevent a full understanding and appreciation of the fact that Lumbee People already have a well-developed body of knowledge about their identity that combines centuries of traditional knowledge with decades of work by scholars who collaborate with us. Research that is not consciously aware of its prejudices can fuel a vicious cycle of harm that elevates colonial myths and diminishes the perspectives and voices of Indigenous peoples, an approach that has come to be known as “extractive research.”

As environmental researchers Dominique David-Chavez and Michael Gavin describe, extractive research is a framework in which “outside researchers use Indigenous knowledge systems with minimal participation or decision-making authority from communities who hold them.” Such research raises ethical issues because researchers and their institutions tend to reap disproportionate benefits from work that is built on community knowledge, labor, and trust.3

Extractive research raises additional concerns for Indigenous peoples when researchers use our knowledge and expertise to advance colonial narratives that erase us or undermine our ability to care for our human and nonhuman relatives. Geneticist and bioethicist Krystal Tsosie and colleagues highlight some of these concerns, including the potential for extractive research to undermine tribal self-determination when Indigenous peoples are only invited to participate in biomedical projects “after the terms of participation have been predetermined by research institutions or funding authorities.” Tsosie and colleagues link the situation to a vicious cycle of “victim blaming and coercion” that exacerbates power imbalances between colonial institutions and Indigenous peoples.4

The stakes are too high for Indigenous peoples to simply shrug off these practices as irrelevant. For Lumbees in particular, political opposition to amending the 1956 Lumbee Act, which would extend full federal recognition to the Lumbee Tribe, relies on narratives that are supported almost entirely by extractive research.

Storytelling holds us accountable to the larger communities to which we—and our narratives—belong.

Here, we include two stories—one from each of us—that converge around our shared experience with extractive research involving Lumbee identity. The experiences prompted us to reflect on broader contexts and legacies of harm to Lumbee people. In particular, the experiences helped us to see certain research practices as not only harmful, but as the exact opposite of the gifted responsibility that comes with storytelling. As with Indigenous peoples everywhere, Lumbees rely on stories as an important way to communicate information about who we were, who we are, and who we will be. Storytelling holds us accountable to the larger communities to which we—and our narratives—belong. These are the stories we tell.

Ryan

My elders taught me that my last name, Emanuel, originated with an ancestor of ours, an Indigenous man who was born around the turn of the eighteenth century. The ancestor took a settler’s first name and used it for his own last name. As my elders shared, this name-taking happened somewhere along the lower reaches of the Roanoke River—an area that is in or near present-day Bertie County, North Carolina.

The story that my elders taught me has been transmitted orally for approximately three hundred years. Abbreviated versions have been written down from time to time, but the full story exists in the oral tradition of Lumbee and Coharie people—two American Indian tribes with whom my family name is associated. The story preserves a few additional details associated with my family’s name-taking, but the details are not especially remarkable. There is no intrigue, war, calamity, or scandal. The truly remarkable thing about the story is that it is one of the only accounts about the creation of a family name among Lumbee or Coharie people. It is one vibrant strand in a larger oral tradition that roots both tribes to the Coastal Plain of present-day North Carolina.5

The oldest person that I remember sharing this story was my great-great-aunt Lottie. Aunt Lottie was born around the turn of the twentieth century. From my childhood, I recall her as a softspoken widow in her eighties, a meticulous gardener who lived down a sandy track in the heart of Saddletree, one of several core Lumbee communities in Robeson County. My aunt lived to be more than one hundred years old, and as an adult I realized that beneath her quiet demeanor lay a deep well of lived experience. She spent her youth in a community of Lumbee turpentine laborers who sojourned in Georgia during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. She taught school and survived the 1918 influenza pandemic in that community before returning to North Carolina with the remaining sojourners. Seventy years later, she guided a busload of Lumbees back to the exact site of the abandonded settlement to pay respects to ancestors who were buried there. Aunt Lottie was a living link between the nineteenth century, when her parents were born, and the twenty-first century, when my children (some of her third great nieces and nephews) were born.

I also heard the story of our name-taking from my father, from various aunts and uncles, and from other Lumbee and Coharie people. The story is not ubiquitous among Lumbees and Coharies, but many people in these communities know the general outline. Details, including the names of other family members and the names of settlers who were involved, make it possible to distinguish my ancestor from similarly named individuals who appear in colonial records from that period.

Colonial records are sparse from this time and place, and my ancestor probably had little reason to appear in them anyway. He apparently paid no taxes or rent, and probably spent much of his life beyond the jurisdiction of colonial authorities. It is also unclear what the settler was doing on the lower Roanoke River at the turn of the eighteenth century or why my ancestor took this name. Perhaps he was related to the settler by blood or adoption. Or perhaps my ancestor simply liked the settler’s name and took it for his own. The story is silent on these details, but had the story not survived for three centuries, my family would have no direct knowledge whatsoever about the origin of our name.6

Our story has been transmitted orally for three centuries despite disruptions to our ancestral languages and enormous pressure to assimilate into the South’s historical racial binary. Critically, the story does not exist in a vacuum; it includes metadata—an accompanying explanation of how the story passes from generation to generation. For example, my great-great-aunt explained that she learned the story from her grandfather, who learned the story from his grandfather, who was the grandson of the ancestor who first took our name along the Roanoke River. The narrative is incomplete without this chain of custody that gives an account of its transmission from generation to generation. In a way, this accounting resembles present-day blockchain technology—a method used to maintain the integrity of digital currency through a publicly accessible ledger of transactions. For Lumbee and Coharie people, the record of who told the story to whom is a form of authentication that serves a similar purpose. Ours is a much more ancient method that allows us to recall our histories and to account for how we know them to be true.7

In the early 1990s, years before the rise of genealogy websites and Internet forums, my family reconnected with distant relatives whose ancestors had left the Southeast sometime between the War of 1812 and the Civil War. My branch of the Emanuel family, which stayed close to our ancestral territory, remembered the departure of their ancestors, but the family branches had lost contact generations ago. When the long-estranged relatives visited North Carolina, one of the first things they shared with us was the story of our name-taking on the lower Roanoke River. It was the same story that we carried; only the chain of custody differed.

These distant relatives went by the eighteenth-century version of our surname, Manuel. It is likely that few of my ancestors could read or write in English before the late nineteenth century, and historical documents refer to us as both Manuel and Emanuel during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. I like to think that our speech patterns included extra syllables that made it difficult for scribes to discern between Manuel and Emanuel, but no one knows for sure. In any case, one of our stories credits the recent spelling to Enoch Emanuel, a relative who promoted education and English literacy among Coharie people around the turn of the twentieth century. Just as mutations in strands of DNA pinpoint branches in the tree of life, two different spellings of our name help us to understand relationships between branches in our family tree.8

The story of my last name illustrates various ways in which oral traditions carry information. The story itself gives details about the time and place of my name’s origin. Metadata tracks the transmission of the story from generation to generation. Other information (e.g., the story of Uncle Enoch) helps explain kinship between various groups, such as the Manuels, who left the region, and the Emanuels, who mainly stayed. The story also explains why Coharie and Lumbee families named Manuel or Emanuel are not related (or at least not closely related) to most other people in the world with these names. On this point, the oral tradition suggests that the names are false cognates—they look the same, but they originated in different times and places.

The name-taking account matters to other Coharies and Lumbees who are not Emanuels because it is part of a larger oral tradition that traces our ancestors’ migrations across the Coastal Plain and even across the North American continent. The Coastal Plain has been our home longer than our stories recall—since time immemorial. My family’s name-taking story also helps to trace kinship between Lumbees and Coharies, who are not only neighboring tribes but also close relatives.

Occasionally, the story of my last name draws attention from outsiders. In the 1930s, a team of anthropologists conducted research on Lumbee people during one of several investigations by the federal government to determine if we possessed sufficient “Indian blood” to become recognized under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. The anthropologists conducted pseudoscientific studies on dozens of Lumbees, classifying them as Native or non-Native people by measuring their heads and recording characteristics of their hair, skin, eyes, and fingernails. Researchers also interviewed test subjects and members of their families. During an interview with one of my relatives, an anthropologist mentioned a version of the Emanuel origin story penned by Uncle Enoch twenty years prior. When the interviewer asked if my relative had learned our family’s origin story by reading Enoch Emanuel’s publication, my relative replied, “No. I remembered what my grand uncle told us when we were children.”9

Anthropologists in the 1930s largely dismissed testimony by my relative and other Lumbees whom they interviewed. Instead, they relied almost exclusively on racialized—and now discredited—stereotypes about Native peoples’ physical appearance to conclude that most of the subjects were ineligible for federal recognition. My relative who was interviewed about Enoch Emanuel’s publication was not a research subject himself but testified on behalf of his nephew, who was. Researchers closed the case on his nephew by declaring that the man’s eye color, hair texture, and skull shape made him “of predominantly white stock” and gave him insufficient “Indian blood” for federal recognition under the Indian Reorganization Act. Later generations of scholars acknowledged that these methods were both pseudoscientific and also rooted in racist stereotypes. But Lumbee people still live with the nearly century-old decision by anthropologists to elevate pseudoscience over oral tradition and other lines of evidence about our history and identity.

Still, today, the Emanuel surname confuses people who are not familiar with Lumbee or Coharie oral traditions. I receive political mail and advertisements in Spanish and have been greeted in Spanish because of my last name. Jewish synagogues send outreach materials to my home, presumably because my last name is also a Hebrew phrase that means “God with us.” These cases of mistaken identity do not offend me. I assume that they are well-intentioned, honest errors based on assumptions that my name implies cultural or genetic connections to Spanish-speaking or Jewish peoples. I do not expect outsiders to Coharie and Lumbee culture to know that my name sprang from an eighteenth-century encounter on the lower Roanoke River.

But recently I encountered a different case of mistaken identity. It involved an academic study that drew inferences about Lumbee origins based on commercial ancestry DNA tests, last names, and additional information. In the study, researchers speculated that Croatians and Sephardic Jews settled in present-day North Carolina during the sixteenth century and were among the ancestors of present-day Lumbee people. At face value, the researchers’ assertion is trivial—Lumbee ancestors, like many other groups of Indigenous people in the Southeast, brought diverse outsiders into their families and communities. Lumbees have no oral traditions or written records about Croatian or Jewish ancestors, but there would be nothing unusual about diverse genetic ancestry among our people. But something else struck me as unusual.10

The study claimed that the researchers’ DNA data, which came from more than two thousand individuals, were collected exclusively from “registered” members of the Lumbee Tribe, and that the tribe had been involved for several years in a commercial ancestry DNA testing program. In particular, the study asserted that “the Lumbee began their program of DNA testing in 2004″ and that “all DNA test results given in the Project are for registered tribal members.” Simply put, these assertions implied that the research subjects were enrolled tribal members who participated in a tribally sanctioned program.11

As both a Lumbee person and a scholar, these methodological details stuck out to me. Not only was I unaware of any involvement by the Lumbee Tribe in ancestry DNA testing, but I also knew that despite prolific marketing by testing companies, these products and the data they provide are uninformative for purposes of tribal identity and enrollment. The study also included a table described as “Lumbee Names of Sephardic Jewish Origin” that listed dozens of last names found among Lumbee people, including mine. The researchers did not mention Lumbee and Coharie oral traditions about my name’s origin, nor did they acknowledge that some names in their table have only become associated with the tribe in recent decades; they were not part of our historic community. Family names can be unreliable markers of ethnicity, nationality, or tribal membership, particularly when they are not interpreted through a lens that acknowledges the complexity of stories that they represent. Any list of “Lumbee names” should be interpreted through this lens, together with a clear understanding of Lumbee history and culture and a general understanding of the symbolic and malleable nature of names. I supposed that tribal enrollment records might serve as a starting point for researchers to create such a list, but I was unsure about the Lumbee Tribe’s policies for sharing this kind of information. I reached out to Karen Bird, a colleague who works for the Lumbee Tribe, for clarification about the genetic study and list of names.12

Karen

When Ryan contacted me at the Lumbee Tribal office in 2021 to share claims about Lumbee genetic data and a tribally run DNA testing program, I was ambivalent but intrigued. Outside opinions on Lumbee identity are not new to me; I have encountered a multitude of narratives that purport to tell me who I am. I was in my twenties when I began to encounter narratives that were either extremely hostile or condescendingly dismissive of the stories and oral histories that shape my identity as a Lumbee person. These stories are part of me. They tell me who I am. My family—and by extension, my People—know these stories and share them with me. And because of this dynamic connection and interaction, I belong.

These stories are part of me. They tell me who I am.

In the oral tradition, stories are able to convey truths in a way that static records cannot begin to approach—truths of identity, truths of ontology that have belonged to a People since time immemorial. Renowned author, activist, and advocate for Indian People Vine Deloria Jr. compellingly asserts in much of his writing that stories in the oral tradition are important, valid, and significant to defining identity. Deloria succinctly notes, “Traditional Indian knowledge is at least as accurate and complete as what orthodox science has put together.” Researchers and commentators that belittle these truths and openly disregard oral traditions and the stories of a person, or a People, do much damage. They steal gifts and seek to take away inherent responsibilities.13

Since those first encounters with dubious reports and extractive research related to my People, I have grown even more appreciative of sound, scholarly studies. I am also more aware of the pitfalls and landmines in this area, so the research that Ryan shared gave me pause. I had never heard of the Lumbee Tribe operating a DNA ancestry program, as the research article claimed, and subsequent conversations with our enrollment department director and interim tribal administrator both confirmed that we do not operate, nor have we ever operated, a DNA ancestry program.

After delving further into the article’s claims, Ryan and I were able to pinpoint an affinity group on an ancestry DNA website that roughly matched the description of the DNA project described in the journal article. The affinity group had no connection to the Lumbee Tribe, and group membership was open to anyone who believed they may share ancestry with Lumbees or other American Indians from southeastern North Carolina. The group provided people with an avenue to share the results of their commercial DNA ancestry tests with one another.14

Ryan’s eventual correspondence with the group administrator revealed that non-Native people with no connection to the Tribe created the group, which at one time had the word “Lumbee” in its name. Group administrators changed the name after reaching out to the Lumbee Tribal government and finding that the government had no wish to be involved with the project. Indeed, the Lumbee Tribal government does not use DNA ancestry tests to determine tribal enrollment, and only uses DNA tests when necessary to determine paternity. DNA testing for purposes of tribal enrollment and/or determining Native American identity is problematic on many fronts. Involvement in such a project would have provided little value for the Lumbee Tribe, and could have created unnecessary confusion about our enrollment criteria.15

Instead, the Lumbee Tribe uses two specific criteria for enrollment. First, enrollees must biologically descend from one or more individuals listed on our base rolls. These rolls, mostly from the late 1800s and early 1900s, include membership lists from Indian churches and schools created by our ancestors and located in our tribal communities. Second, enrollees must prove contact with core Lumbee communities in our present-day territory, which comprises Robeson County and adjacent counties in North Carolina. Contact may be historical or present-day, and the Lumbee Tribal government creates policies to define how contact can be determined in the twenty-first century.

Like most other tribes in the United States, our tribal government rejects DNA tests for enrollment purposes (other than for establishing paternity). According to scholars Kim TallBear and Deborah Bolnick, DNA ancestry tests “can fail to detect Native American ancestry in individuals with Native American ancestors, and incorrectly identify it in others who do not have such ancestors.” Additionally, there are multiple factors that establish who is or is not enrolled in a tribe. Each sovereign tribe establishes these factors or criteria. It is their responsibility to do so. The Lumbee values of kinship and connection to place, as well as ancestry, determine ours—criteria that DNA ancestry tests cannot replace or reflect.16

Clearly, the article that Ryan shared misstated the tribe’s involvement in the DNA testing program. The article’s claim that all two thousand or so research subjects were enrolled tribal members also seemed suspect. Our Tribal Enrollment Department confirmed that they had not interacted with the affinity group or with the researchers who conducted the study to verify tribal enrollment of the indicated research subjects. Of course, study participants could voluntarily disclose their enrollment status, but there was no indication that the researchers had requested this information.

If researchers had conducted a study on the DNA of a group made up exclusively of tribal members, their work would likely have required approval and monitoring by the Lumbee Tribal Council and the Health Committee that currently acts as our Tribal Institutional Review Board. There is no record of such a study or an approval. So if the study had focused exclusively on tribal members’ DNA, as claimed, it would have been unauthorized. More likely, the research subjects were not all members of the Lumbee Tribe, as claimed, and it is possible that few, if any, of the research subjects were enrolled tribal members.

In email correspondence with Ryan, one of the affinity group’s administrators confirmed—in no uncertain terms—that the group made no claims whatsoever about tribal enrollment or identity of group members. The administrator explained that group members may or may not identify as American Indian, and that some people join the group simply to find out if they share ancestry with other group members. Thus, it was impossible to determine how many, if any, of the participants in the study were enrolled tribal members. It was also impossible to tell how many participants were non-Native individuals who were simply curious about their deep ancestry. Intentionally or not, it seemed that the article had misstated the involvement of enrolled tribal members in the study and mischaracterized an online affinity group as a tribally sanctioned entity.

The study’s assumption that all of the project participants were members of the Lumbee Tribe was probably untrue and certainly unverified. The authors specifically stated that “central to this paper’s thesis is that DNA testing of the 2,724 Lumbee tribal members will indicate the presence of 1) Sephardic Jewish male haplotypes, 2) Sephardic Jewish female haplotypes, and 3) male Croatian haplotypes.” Whether or not Lumbee people have genetic links to sixteenth-century Jewish and Croatian settlers, the fact that the key conclusions of this research were based on unfounded assumptions about tribal membership and identity casts doubt on the rigor of the study. Additionally, the study may have received an undeserved aura of authenticity because of its claims about the tribe’s involvement in the project. Ironically, if the researchers had contacted the Lumbee Tribe at any time during their work, tribal staff could have clarified information about Lumbee surnames and warned about ethical concerns over DNA ancestry testing and research on any actual tribal members.17

Reckoning with Extractive Research

Our intersecting stories highlight a need to reckon with research that claims to have authoritative information about Lumbee identity while ignoring what we have to say about ourselves. “Talking over” Indigenous people is a hallmark of extractive research. While researchers in many disciplines are slowly becoming self-aware, if not self-critical, of extractive practices, there are still quarters of academia and government where it is deemed acceptable—even desirable—to take knowledge or physical material from a community without meaningful involvement or accountability. One of the most prominent examples in recent decades involves genetic research conducted on Havasupai people in Arizona who agreed to participate in a diabetes-related study but learned, much later, that their genetic material had been shared with other researchers and used for other projects without their knowledge or consent.18

Lumbee people have been subjects of extractive research for a century—even longer if one includes historians and naturalists who preceded the coming of university-based researchers to our communities in the early 1900s. Much of this research fixates on (or even fetishizes) the origins and collective identity of Lumbee people. Some of the work ignores or is unaware of what Lumbee people have to say about their own identity, or it devalues Lumbee perspectives in favor of outside voices, including the voices of other extractive researchers.19

Researcher Paul Heinegg’s work provides an example. As Heinegg stated in 2006 to a Capitol Hill reporter, he believed that Lumbees were not American Indians but “part of a group of light-skinned African Americans who owned land during the Colonial period.” Heinegg’s work involved scouring seventeenth- and eighteenth-century wills and other records to find Lumbee surnames among people who were enslaved or indentured in Virginia and who were described as Negro or Mulatto. He believed that these individuals migrated to areas around present-day Robeson County and later invented an American Indian identity to avoid treatment as African Americans during Jim Crow Segregation.20

To support this idea, Heinegg constructed genealogies that linked enslaved or indentured individuals in Virginia to more than a dozen Lumbee families in North Carolina. In most cases, however, Heinegg found no evidence to support links between individuals in the two colonies. In the absence of evidence, he simply assumed that the individuals were related because their surnames were the same or very similar to one another’s. Heinegg’s genealogies use words like “probably” and “perhaps” to downplay the lack of documented connections between individuals in Virginia and North Carolina. But subsequent researchers—and Heinegg himself—came to treat his speculation as evidence that Lumbees are not actually American Indians.21

Heinegg’s work typifies extractive research partly because it amplifies and reinforces other extractive research. The cycle reawakens old ethical issues and raises new concerns around informed consent, respect for Indigenous knowledges, and the potential for group harm. Moreover, Lumbee people were not involved in Heinegg’s project, and his work never engages with Lumbee stories, with our traditional knowledge, or with academic work on American Indians (or American Indian slavery) in the colonial South. Lacking these essential connections, his work fails to add to or acknowledge the rich story of Indigenous identity in the South. Instead, it mainly circulates among those who find it uncomfortable or inconvenient that American Indians survived three centuries of colonialism and racial oppression in eastern North Carolina.22

The 2019 DNA study and the anthropological study from the 1930s were not just extractive. They also highlight ways that researchers use the trappings of science to advance their preconceived ideas about Indigenous identity. Regardless of researchers’ intentions, these ideas prop up colonial myths that Native peoples died, moved away, or otherwise disappeared so that settlers might guiltlessly inherit the land. These particular studies cause harm by failing to take Lumbee Indigeneity seriously; by failing to understand that blood is only one contributing factor to Indian identity; and by failing to realize that Indigenous identity is not theirs to dictate. More generally, this vein of extractive research reinforces concepts such as blood quantum—the controversial idea that American Indian identity can be measured and managed as a fraction of one’s ancestry—and other convenient beliefs that ultimately erase Indigenous peoples from public consciousness. Researchers may be oblivious to the ways in which their studies invoke these concepts, but their ignorance does not reduce the potential for harm to Indigenous peoples.23

Studies that fail to engage with oral traditions and other forms of knowledge that exist within Indigenous communities are guilty of “talking over” Indigenous peoples in ways that are not only disrespectful, but also lead to weak or flawed scholarship. These weaknesses can take the form of blind spots that could be readily addressed by Indigenous insight. Sometimes, blind spots can be addressed by simple, clarifying questions that do not even involve oral traditions or closely held knowledge. In the case of the 2019 DNA study, a phone call to the tribal offices or a review of the tribal website might have cleared up confusion about tribal enrollment protocols. Even a close reading of the affinity group’s website could have signaled to researchers that their subjects were not, in fact, a group of enrolled tribal members but a collection of individuals whose connections to the tribe were entirely unknown. Instead, the 2019 study adds to the long list of studies that purport to solve some mystery or another involving Lumbee identity.24

Lumbees might be inclined to chuckle at the naïveté of the researchers, but extractive studies come back to haunt us. The findings of the 1930s study—that only twenty-two of 209 research subjects had sufficient “Indian blood” to be recognized under the Indian Reorganization Act—appeared decades later in lobbying efforts against complete recognition for the Lumbee Tribe. Perhaps the most egregious misuses of the study came from Howard Tommie, president of an advocacy group for several federally recognized tribes in the Southeast. Tommie cited the study while lobbying against an early effort to amend the 1956 Lumbee Act. In a 1974 letter to all federally recognized tribes and tribal organizations, Tommie wondered how twenty-two people in the 1930s could possibly multiply into a tribe of fifty thousand by the 1970s—a disingenuous interpretation of research findings that by that time had been dismissed as racist pseudoscience. The 1974 lobbying effort and others up to the present have leaned heavily on these findings and on other extractive studies.25

Consider an additional example of extractive scholarship with long-term negative repercussions for efforts to amend the 1956 Lumbee Act and fully acknowledge the sovereignty of the Lumbee Tribe. William S. Pollitzer, a medical anthropologist and professor at UNC-Chapel Hill during the twentieth century, collected blood samples from more than one thousand Lumbee schoolchildren and college students in 1958. He collected the samples under the auspices of studying differences in blood types and the prevalence of blood disorders (e.g., sickle cell disease) among various groups of people in the Southeast, including Lumbee, Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, and other tribes of present-day North and South Carolina.

Pollitzer and his team published the study and also shared test results with the families of the Lumbee youth whose blood they sampled. But the team also did much more in ways that resemble the Havasupai case and other extractive incidents. Without informing the families or the Lumbee community, Pollitzer used data from the Lumbee blood tests in later research that aimed to advance emerging ideas about genetics and race. For that study, he fed information about Lumbee blood characteristics (frequencies of blood types and certain blood proteins) into newly developed mathematical models designed to determine the composition of so-called “hybrid human” populations.26

Pollitzer assumed Lumbees descended from American Indians, Europeans, and Africans, and he instructed the models to treat Lumbee blood as a mixture of three contemporaneous sources for which he also had blood data: Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians from the Qualla Boundary in western North Carolina; African Americans, whom he identified as Gullah Geechee people from Charleston, South Carolina; and a group of post–World War II hospital patients in London, England. Notably, Pollitzer and the models wrongly assumed that all four 1950s study groups represented completely endogamous populations whose gene pools had been sealed off, for centuries, from the outside world.27

Pollitzer’s outrageous exercise is a striking example of confirmation bias. He assumed that Lumbee blood characteristics represented an unknown mixture of three specific groups of people—groups for whom he conveniently had data on hand. The limited models performed exactly as their flawed design allowed, by indicating that Lumbee blood was, indeed, a mixture of the predetermined groups. Not only that, but Pollitzer used the model results to authoritatively report mid-twentieth-century Lumbee blood samples as a mix of contemporary Cherokee, Gullah Geechee, and English blood—down to a fraction of a percent for each group.

The exercise gave an air of scientific precision to what was an absurd idea: that three groups chosen for Pollitzer’s convenience were the exact and only genetic ancestors of Lumbees, and that the genetic characteristics of all four populations (Lumbees and the three other groups) had been frozen in time for centuries. Pollitzer buried a few qualifying statements on these topics in the methodological details of his study, but he chose to highlight conclusions that erroneously reduced Lumbee identity to a recipe of blood characteristics from other groups of people.

Pollitzer did not appear to have any special interest in Lumbee history, culture, or identity beyond a desire to put the mathematical models through their paces. There is no indication that he considered or respected Lumbee knowledge and ways of being; he simply used Lumbee blood samples—without consent—to further his interests and ideas about identity, race, and genetics. Pollitzer certainly did not acknowledge Lumbee identity in terms of kinship, place, or shared experiences—concepts that are extremely important to Lumbee ways of knowing and being. Instead, he described Lumbee identity solely in terms of a biological hybrid—a mixture of three “racial groups” whose relative proportions purportedly could be disentangled using mathematical models. Pollitzer’s ideas are not that far removed from those of researchers who studied Lumbee people during the 1930s. Both groups construed Indigenous identity as primarily racial, and both asserted that race could be measured—either through outwardly visible characteristics or through genetic information held in blood samples.28

The human hybrid model results featured prominently in Pollitzer’s later work on race and genetics. He went on to a distinguished career in anthropology and human biology, editing a major academic journal, presiding over two professional societies, and receiving awards for his scholarly work. Meanwhile, Lumbee people were left to deal with the fallout of his research, including the weaponization of his work in lobbying efforts against amendments to the 1956 Lumbee Act. In the 1990s, one of the tribes involved in the advocacy group that lobbied against Lumbee recognition submitted a report to Congress that aimed to discredit Lumbee Indigeneity by citing Pollitzer’s blood research. Prominent non-Lumbee scholars, including some who had worked closely with Lumbee people, sent scathing criticisms of the report to Congress. William Starna, a professor and ethnologist of eastern woodland tribes, called the report “grossly inept,” “deceptive,” and “little more than a racist tract,” before dismissing it as “written for the sole purpose of discrediting and ridiculing the Lumbee Indians.”29

Pollitzer reached out to the Lumbee community only after backlash to reporting on his study—nine years after it was published in the academic literature and fifteen years after collecting blood samples from Lumbee youth. In a letter to the editor of a local newspaper read by many Lumbees, Pollitzer admitted that many of the model requirements had not been met, and that he had made “hypothetical approximations” about Lumbee ancestry in order to successfully execute the models.

Research by Pollitzer on Lumbees and other marginalized groups bolstered decades of extractive research on minoritized peoples. One idea that lingers in this vein of work is that blood—and, now, DNA—is essential for answering questions about collective identity and, especially, about the collective identities of Indigenous peoples. The same idea underpins the concept of blood quantum and other tenets of colonialism and imperialism that survive to this day in the largely unstated assumptions and preconceptions of many researchers.30

Biological ancestry is an important element in the formation of identity, but it is by no means the only element, especially for Indigenous peoples. It exists alongside the lived experiences of generations and the oral traditions and stories of a People that hold definitive knowledge. Kiowa poet and Pulitzer Prize–winning novelist N. Scott Momaday invoked the importance of lived experience in a conversation about a character from his novel House Made of Dawn. Momaday writes, “Of course he is an Indian man, which is to say that he thinks of himself as an Indian man, according to his experience.” He does not diminish biological ancestry, but focuses attention on lived experience as another crucial hallmark of indigeneity. Knowingly or not, researchers who elevate measurements of body, blood, or DNA above Indigenous accounts of our own identities are guilty of talking over us in ways that undermine centuries of Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination. Such work promotes colonization by seeking to control our stories, and, ultimately, to control our lives.31

We recognize that our biological ancestry shapes our identity as Indigenous people, and we emphatically affirm the other shapers of our identity, including our kinship ties; our connections to place—especially the landscapes and waterways that are integral to our ways of being; our oral tradition and lived experiences as tribal people; and our political status as tribal citizens. Regardless of the intentions, extractive research destroys or diminishes the ability of a People to tell their own stories. It also burdens our freedom to define ourselves in ways that honor our lived experiences and traditions.

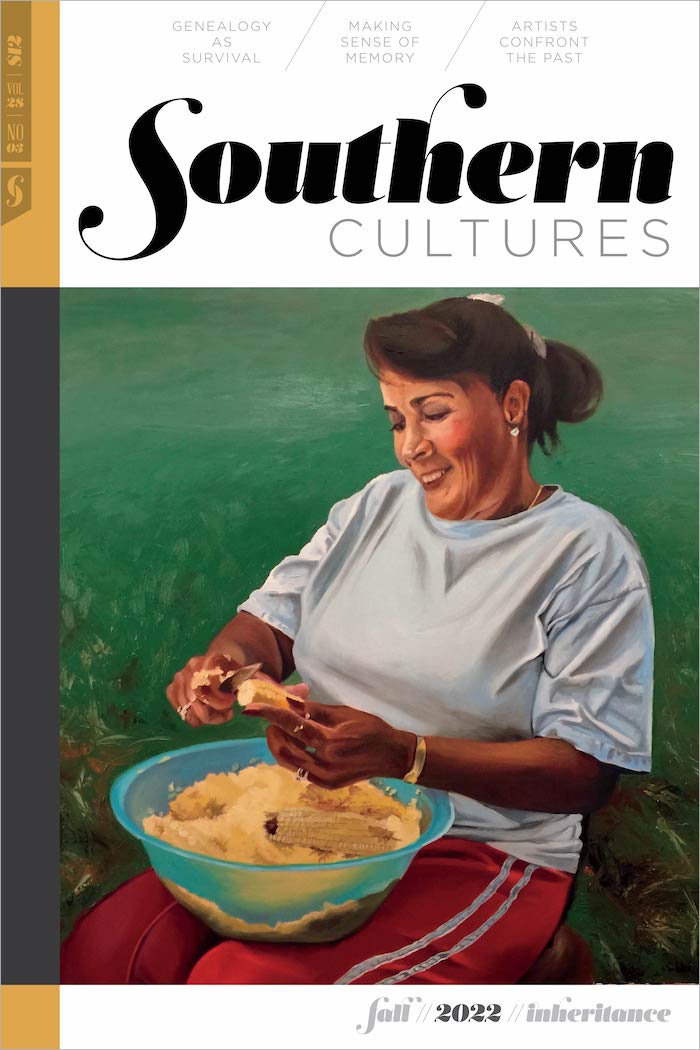

This essay was first published in the Inheritance Issue (Fall 2022).

Ryan E. Emanuel is associate professor of hydrology at Duke University and an enrolled member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. Based in the Nicholas School of the Environment, he studies water and ecosystems in his ancestral homelands and beyond. Emanuel also studies barriers to Indigenous participation in environmental decision-making.

Karen Dial Bird is an enrolled member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina and serves as the Tribal Grants and Planning Manager. She delights in both the written language and the oral tradition, and in delving deeply into the history and culture of her People.

- For detailed discussions of stories as scholarship, see Bryan McKinley Jones Brayboy, “Toward a Tribal Critical Race Theory in Education,” Urban Review 37, no. 5 (2005): 425–446; and Aman Sium and Eric Ritskes, “Speaking Truth to Power: Indigenous Storytelling as an Act of Living Resistance,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 2, no. 1 (2013).

- See the “origin myth” discussed in Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States (Boston: Beacon Press, 2014), 46. See also the criticism of land as pristine wilderness in William Cronon, “The Trouble with Wilderness: Or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature,” Environmental History 1, no. 1 (1996): 7–28. In the monumental work Custer Died for Your Sins, Vine Deloria Jr. condemns assumptions and stereotypes about Indigenous peoples as “(m)ythical generalities of what built this country and made it great.” Vine Deloria, Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1988), 52. Brittany Hunt and colleagues demonstrated recently that harmful stereotypes surrounding Indigenous peoples are alive and well in the United States through a study of American Indian student experiences in large urban school systems. Brittany D. Hunt, Leslie Locklear, Concetta Bullard, and Christina Pacheco, “‘Do You Live in a Teepee? Do You Have Running Water?’ The Harrowing Experiences of American Indians in North Carolina’s Urban K-12 Schools,” Urban Review 52, no. 4 (November 2020): 759–777.

- Dominique M. David-Chavez and Michael C. Gavin, “A Global Assessment of Indigenous Community Engagement in Climate Research,” Environmental Research Letters 13, no. 12 (2018).

- Krystal S. Tsosie, Joseph M. Yracheta, Jessica A. Kolopenuk, and Janis Geary, “We Have ‘Gifted’ Enough: Indigenous Genomic Data Sovereignty in Precision Medicine,” American Journal of Bioethics 21, no. 4 (April 2021): 72–75.

- Ryan’s family name also belongs to relatives who reject both Lumbee and Coharie political identity and instead identify as Tuscarora. The topic of Tuscarora political identity in twenty-first-century North Carolina is beyond the scope of our essay.

- Indigenous people living in the British colonies of Virginia and North Carolina around the turn of the eighteenth century sometimes adopted European first names, last names, or both. For examples relevant to Lumbee ancestors, see J. Cedric Woods, “Lumbee Origins: The Weyanoke-Kearsey Connection,” Southern Anthropologist 30, no. 2 (2004): 20–36.

- There are at least two instances in which parts of the Emanuel family’s oral tradition were recorded or published. A few details were printed in a 1916 pamphlet that described the Indigenous people of Sampson County, North Carolina (ancestors of present-day Coharie people). George Edwin Butler, “The Croatan Indians of Sampson County, North Carolina. Their Origin and Racial Status. A Plea for Separate Schools” (Durham, NC: Seeman Printery, 1916), https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/butler/frontis.html. Lumbee historian Adolph Dial made passing reference to the Emanuel story in a 1972 oral history interview for the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program at the University of Florida. See “Interview with Adolph Dial August 25 1972,” George A. Smathers Libraries Digital Collections, University of Florida, https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00007010/00001. Technologists have recently proposed the application of blockchain or “distributed ledger” concepts to genealogical research. This idea parallels what we describe here—metadata attached to oral traditions. Michael Meth, “Chapter 2: Blockchain Primer,” Library Technology Reports 55, no. 8 (2019): 7–12. Scholars indirectly reference the practice of explaining how a story was passed along in discussions about unique aspects of Lumbee speech. In particular, Dial and Eliades comment on preambles given by Lumbee storytellers to explain the genealogical provenance of a story. Adolph L. Dial and David K. Eliades, The Only Land I Know: A History of the Lumbee Indians (San Francisco: Indian Historian Press, 1975), 11. Lumbee people (and other Indigenous peoples) assume their ancestors transmitted oral traditions accurately and in good faith, the same assumptions that historians and scholars often apply to other record-keepers.

- Ryan’s Uncle Enoch was a contemporary of George Edwin Butler and is featured prominently in his 1916 pamphlet advocating for resources to support schools for Native Americans in Sampson County; see notes 7 and 9.

- The interviewer referenced the published account mentioned in notes 7 and 8. Quote from “Testimony of Edward Emanuel” in McNickle, D’Arcy, Edward McMahon, and Carl Seltzer, “Report on Application for Registration as an Indian: Case No. 25, Sylvester Emanuel,” Washington, DC, June 10, 1936.

- Elizabeth Hirschman, James Vance, and Jesse Harris, “DNA Evidence of a Croatian and Sephardic Jewish Settlement on the North Carolina Coast Dating from the Mid to Late 1500s,” International Social Science Review 95, no. 2 (2019).

- Hirschman, Vance, and Harris, “DNA Evidence,” 11.

- Kim TallBear examines the tendency to conflate Indigenous identity with the results of commercial genetic tests in Native American DNA: Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

- Deloria Vine, “History in the First Person: Always Valued in the Native world, Oral History Gains Respect among Western Scholars,” Tribal College: Journal of American Indian Higher Education 6, no. 4 (Spring 1995). Deloria challenges the dominant view that “information possessed by non-Western peoples … becomes valid only when offered by a white scholar recognized by the academic establishment” (33). Deloria notes that “the non-Western, tribal equivalent of science is the oral tradition, the teachings that have been passed down from one generation to the next over uncounted centuries.” These teachings were often conveyed in stories. They carried knowledge about origin and migration, as well as “precise knowledge of birds, animals, plants, geologic features, and religious experiences of a particular group of people” (36). Vine Deloria Jr., Red Earth, White Lies: Native Americans and the Myth of Scientific Fact (Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing, 1995). Deloria demonstrates the validity of oral tradition and the depth of insight available within the teachings throughout this work.

- According to an archived version of the website from 2017 (two years before the research in question was published), the website was “open to anyone who believes they are descendants of a LUMBEE Native American” (emphasis in the original). At that time, the website was called the “Lumbee Tribe Regional DNA Project” despite no formal Lumbee involvement. Around 2018, the website was renamed the “Robeson County NC American Indian Regional DNA Project” and the description was revised to note that the site was “open to anyone who believes they are (or could be) descendants of an American Indian, and who desire to determine and/or prove their American Indian heritage when their ancestors are believed to originally be from the Robeson Co., North Carolina vicinity.” See archived versions at Robert B. Noles, “About Us,” LumbeeTribe, Family Tree DNA, accessed July 18, 2022, https://web.archive.org/web/20170302093222/https://www.familytreedna.com/groups/lumbee-tribe/about; and Robert B. Noles, “About Us,” Robeson Co. NC American Indian, Family Tree DNA, accessed July 18, 2022, https://web.archive.org/web/20180523105609/https://www.familytreedna.com/groups/robesonconcamericanindian/about. Most recent version available at: Robert B. Noles, “About Us,” Robeson Co. NC American Indian, Family Tree DNA, accessed January 2022, https://www.familytreedna.com/groups/robesonconcamericanindian/about.

- K. TallBear and D. A. Bolnick, “‘Native American DNA’ Tests: What Are the Risks to Tribes? Native Voice (2004), D2.

- TallBear and Bolnik, “‘Native American DNA’ Tests,” 4.

- Hirschman, Vance, and Harris, “DNA Evidence,” 11.

- LorrieAnn Santos, “Genetic Research in Native Communities,” Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action 2, no. 4 (2008): 321–327; Adam J. P. Gaudry, “Insurgent Research,” Wicazo Sa Review 26, no. 1 (2011): 113–136.

- Two such figures are Mary C. Norment and Hamilton McMillian, prominent non-Indigenous residents of Robeson County during the nineteenth century who wrote about Lumbee ancestors. Mary C. Norment, The Lowrie History, as Acted in Part by Henry Berry Lowrie, the Great North Carolina Bandit. With Biographical Sketches of His Associates. Being a Complete History of the Modern Robber Band in the County of Robeson and State of North Carolina (Wilmington, NC: Daily Journal Printer, 1875); and Hamilton McMillan, “The Croatans,” North Carolina Booklet 10, no. 3 (1911): 115–121.

- Dan Rasmussen, “The Lumbees’ Long and Winding Road,” Roll Call, Washington, DC, July 17, 2006. Also note that Heinegg’s assumption that Lumbee ancestors were African Americans who sought a better situation for themselves in the racial hierarchy of Jim Crow relates to the notion of racial “passing”—an idea that Brewton Berry popularized in the 1960s to explain the preponderance of unrecognized Indigenous groups in the eastern United States. According to Berry (and others who espouse this racist idea), the groups invented tribal identities to improve their social status. Brewton Berry, Almost White (New York: Macmillan, 1963). The flip side of Berry’s argument is that the groups really are who they claim to be—tribal nations that have existed since historic times. In fact, several groups discussed in Berry’s work have been recognized by the federal government in recent years as American Indian tribes, each providing detailed evidence to support their claims. Susan Greenbaum explains how the racist ideas embodied in the work of Berry and others have created major challenges for unrecognized tribes in the southeastern United States. Susan Greenbaum, “What’s in a Label? Identity Problems of Southern Indian Tribes,” Journal of Ethnic Studies 19, no. 2 (1991): 107.

- Heinegg’s work includes genealogies for at least eighteen Lumbee families. Of these, Heinegg found evidence that individuals from six families migrated from Virginia to North Carolina. For all of the other family trees that Heinegg created, he used various phrases like “may have been the ancestor” or “probable descendants” to denote a lack of evidence that genealogists typically use to establish relationships between individuals. For more details on standards of evidence typically used in genealogical research, see Elizabeth S. Mills, “Working with Historical Evidence: Genealogical Principles and Standards,” National Genealogical Society Quarterly 87, no. 3 (1999): 165–184. Heinegg’s work is viewable online at http://www.freeafricanamericans.com.

- Some ethical issues are summarized in Santos, “Genetic Research in Native Communities,” and David-Chavez and Gavin, “A Global Assessment of Indigenous Community Engagement.” Santos, in particular, highlights ethical concerns associated with the use of blood and genetic information using the high-profile example of the Havasupai Nation and academic researchers.

- See note 2. Deloria notes that “tribal peoples were placed at the very the bottom of the imaginary cultural evolutionary scale.” This allowed colonizers to imagine us as animal-like with only “marginal status as human beings.” Deloria, Red Earth, White Lies, 65. For more on blood quantum, see Paul Spruhan, “A Legal History of Blood Quantum in Federal Indian Law to 1935,” South Dakota Law Review 51, no. 1 (2006): 1–50. Quinn Smith Jr. provides a less flattering (but no less accurate) description of blood quantum as a tool used by the federal government to “breed Indians out” of the United States. Quinn Smith Jr., “Real Indians and Fake Indians,” Wellian Magazine, Duke University, January 20, 2021.

- Two recent examples of how Indigenous knowledge systems are becoming more widely recognized and appreciated include fire management in California and water management in New Zealand. William Nikolakis and Emma Roberts, “Indigenous Fire Management: A Conceptual Model from Literature,” Ecology and Society 25, no. 4 (2020); and Gary Brierley et al., “A Geomorphic Perspective on the Rights of the River in Aotearoa New Zealand,” River Research and Applications 35, no. 10 (2019): 1640–1651.

- Letter from Howard Tommie to Regional Indian Liaison, Department of Labor, dated October 17, 1974, Vine Deloria Papers, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

- William S. Pollitzer, Amoz I. Chernoff, L. L. Horton, and M. Froehlich, “Hemoglobin Patterns in American Indians,” Science 129, no. 3343 (1959): 216. Pollitzer adapted the mathematical models that purported to explain the origins of “hybrid” populations from research studies of castes in India. L. D. Sanghvi and V. R. Khanolkar, “Data Relating to Seven Genetical Characters in Six Endogamous Groups in Bombay,” Annals of Eugenics 15 (1950): 52–76.

- William S. Pollitzer, “Analysis of a Tri-Racial Isolate,” Human Biology 36, no. 4 (1964): 362–373. Blood characteristics from hospital patients in London were published in a popular medical text from this period: Robert Russell Race and Ruth Sanger, Blood Groups in Man(Oxford: Blackwell Scientific, 1950). Some present-day anthropologists point out that mid-twentieth century genetic researchers worked under an implicit assumption that they were studying populations that had been genetically isolated for hundreds or thousands of years. Veronika Lipphardt, “‘Geographical Distribution Patterns of Various Genes’: Genetic Studies of Human Variation after 1945,” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 47 (2014): 50–61.

- In addition to Lumbee, Eastern Cherokee, and Gullah Geechee people, Pollitzer conducted research on genetics, race, and identity using blood samples collected from Catawba, Haliwa-Saponi, Seminole, and other American Indian communities and from other marginalized peoples throughout the southeastern United States. Pollitzer published case studies individually and summarized many of them in William S. Pollitzer, “The Physical Anthropology and Genetics of Marginal People of the Southeastern United States,” American Anthropologist 74, no. 3 (1972): 719–734; and Pollitzer, “Analysis of a Tri-Racial Isolate,” 366. See Karen Norrgard, “Human Testing, the Eugenics Movement, and IRBs,” Nature Education 1, no. 1 (2008): 170. Note also that Susan Greenbaum and Veronika Lipphardt are among the social scientists who question the veracity of anthropological research on mixed-race communities in the South and highlight links to discredited ideas from eugenics and race science. Lipphardt, “Geographical Distribution Patterns,” 50–61; and Greenbaum, “What’s in a Label,” 107.

- Pollitzer, “Physical Anthropology and Genetics of Marginal People.” The report to Congress was prepared by a researcher employed by the tribe engaged in lobbying against Lumbee recognition. Ironically, the researcher’s report cited figures from a study that Pollitzer had conducted not on the Lumbee Tribe but on a different tribe. Although Pollitzer substituted terms such as “hybrid” and “isolate” for the names of the tribes that he studied (a halfhearted attempt at anonymizing his research subjects), he included numerous identifying details that would make either tribe instantly recognizable to anyone familiar with them. Thus, the report to Congress is yet another warning about the intellectual hazards of conducting research on a community that one knows nothing about. Kenneth H. Carleton, “Comments on the Lumbee of North Carolina,” Vine Deloria Papers, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University; Letter to Editor, Robesonian, June 6, 1973.

- Susan Greenbaum discusses Pollitzer’s links to Beale, an earlier eugenicist who popularized the study of minoritized groups in the Southeast by anthropologists. Greenbaum, “What’s in a Label?,” 113. However, TallBear and Bolnick speak against this notion of identity in TallBear and Bolnik, “‘Native American DNA’ Tests,” and TallBear, Native American DNA.

- N. S. Momaday, Conversations with N. Scott Momaday (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1997), 152.