I wasn’t much of a reader as a kid, but I carried books around with me so people would think I was one. It was a good look. I surrounded myself with books I didn’t read, something I do to this day: why do I have two copies of War and Peace if I’ve never even read it once? At twelve, I asked my mother for a complete set of Shakespeare’s plays, Signet edition. A twelve-year-old who’s into Shakespeare the way I was into Shakespeare—the way I appeared to be into Shakespeare—is a rare thing, and I was celebrated for it. The collection of his plays fit perfectly on a small shelf in my bedroom, each in its own thin volume. My older sister Holly would bring her friends into my room and point at the Shakespeare shelf. “My little brother is a genius,” she would say, and I did not correct her.

The Signet Shakespeares were beautiful, pristine volumes, and in that condition they remained. I didn’t crack a spine. Months after her original purchase my mother could have returned them to the bookstore and gotten a full refund. Forensics wouldn’t have been able to detect a fingerprint.

A year or so later I did start reading a few books. Kurt Vonnegut, Richard Brautigan, The Metamorphosis, H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds, Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, Poe, Jack London, Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbinders in Suspense and Tales of Terror. These books filled my early teen years. It’s an eclectic collection but taken together, dropped into a vat of boiling water, and left to simmer for fifteen years, they became the starter potion for what would become my books, decades down the line. Throw in a dash of Faulkner, O’Connor, and Percy and I become really delicious.

This brings me to my father. My father was a businessman. He’d built his company from scratch, an import-export firm specializing in dishes and flatware made in Korea and Japan. He named it Wallace International. The company established “continuity programs” for supermarkets: customers could buy a dinner plate one week, salad plate the next, then a coffee cup, saucer, et cetera, until they collected a whole set of dishes. This kept the supermarket patrons, who are historically fickle, coming back to the same Piggly Wiggly, say, every week. He was the King of Continuity for decades, and he made a lot of money, which everyone in the family appreciated but never thanked him for; I know I didn’t. Big houses, ritzy vacations, and a new pair of Converse whenever I wanted them (in every color of the rainbow)—that was the life of privilege he made possible for me.

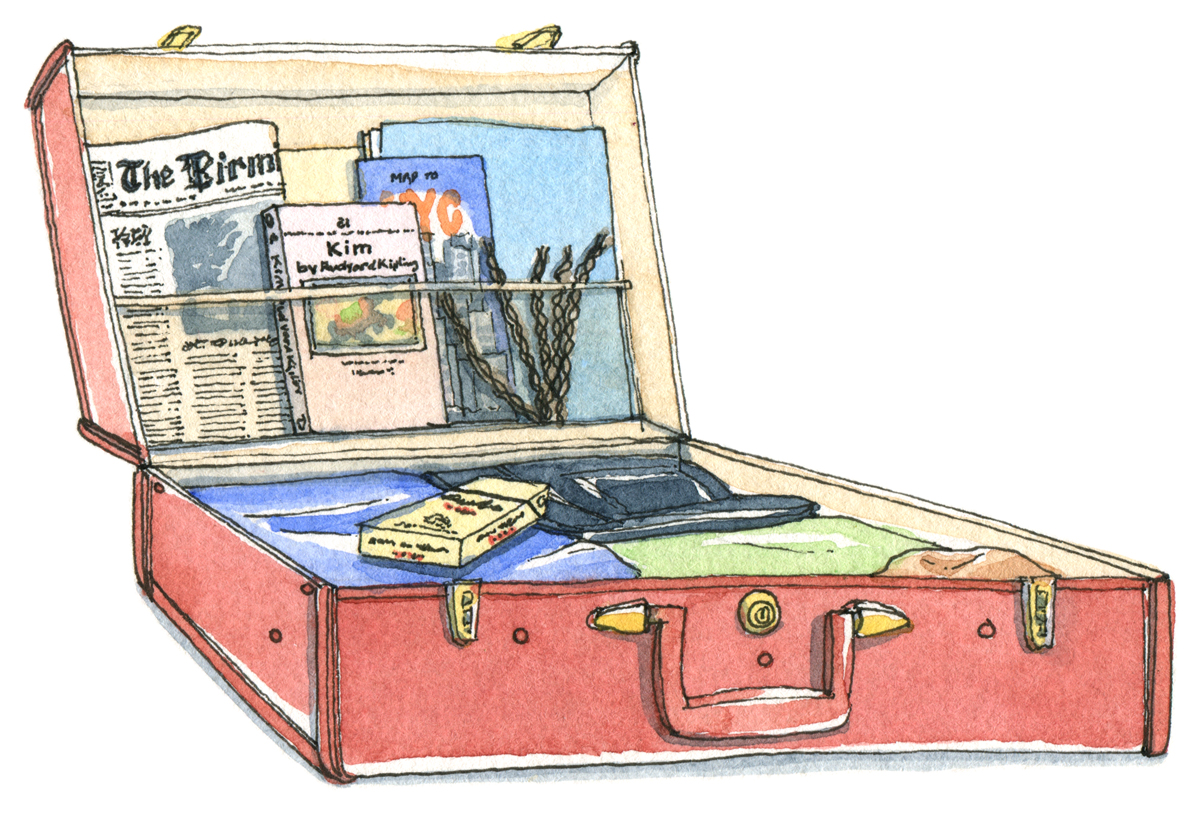

He was gone quite a bit, supporting his family and feeding his own inexhaustible ambitions. We lived in Birmingham, Alabama, but home offices of the bigger grocery chains were out west, or up east, like Safeway, Publix, or Kroger. He also traveled to Japan, where the dishes were made. For almost three weeks out of a month he was gone, and so for almost three weeks a month our family consisted of my mother, me, my two sisters (my third sister had already left home), and Velma, our house cleaner and second-string mother who was there every day, Monday through Friday, and had been since before I was born. There was usually a dog or a cat, too. In his absence we established our routines and relationships, our customs, revised our personalities and hairstyles. When he returned it was like putting up a boarder who also just happened to be your father. His presence changed everything. What was acceptable while he was gone—leaving my shoes in the living room—became unacceptable when he was here. We had to establish a new rhythm, and he had to learn who his children were, because when you’re a kid a lot can happen in a month that, for better or worse, could change you, your whole life. Hearts were broken and healed in his absence, I grew, a dog died. Just as it was for him in Japan or Korea, we spoke a different language, and a good deal of it he couldn’t understand. He was not an outcast so much as he was a stranger. He couldn’t wait to leave his beautiful home and get back on the road. People out there listened to him, appreciated him, respected him. He was an expert packer of suitcases.

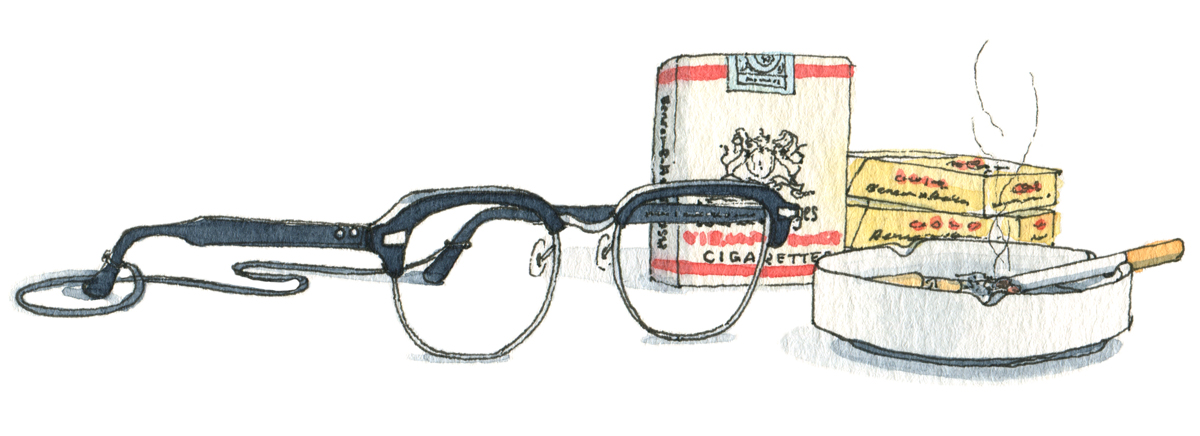

After returning from one trip to Detroit or Trenton or Nagoya or wherever, he noticed me recumbent on the overstuffed couch in the living room, in a kind of peel-me-a-grape posture. I had a book with me; I would wager I was even reading it. In the morning before work he walked around the house in his undershirt and pale blue boxers, small pieces of tissue scattered across his chin soaking up the blood from errant scrapes of the razor, smoking. Cigarettes were his only accessory.

He stopped short when he saw me. “What’s that?”

“What’s what?”

“That.”

“A book?” I said, in the way a fourteen-year-old can supercharge a question mark to irritate his father. My father commanded a far-flung empire of worker bees at his office down the road and across the world, but at home he was treated like a serf, this in the house he had paid for with his own hard-earned money. He gave me his slit-eyed death stare.

“Who’s it by, jerk?”

I held it up so he could see it through the cloud of cigarette smoke gathering around his head. “Kurt Vonnegut?” he said. “Slaughterhouse-Five? Lemme take a look at it.”

He held out his hand for the book. I dog-eared the page I was on before giving it to him. His glasses were suspended halfway down his chest hanging by a black cord, like a necklace in a country where they wore eyeglasses for necklaces. He put them on and read a little bit, and I took this moment to assess him. He was tall, over six feet, with an impossibly big nose and ears at right angles to his head. When he was a kid, boys called him Dumbo and he would beat them up for it. His folks moved around a lot so it became a routine, beating up kids who called him Dumbo. Other than that he was a peaceful child. His eyes were Sinatra blue and when he smiled his mouth took up a lot of real estate on his face. Women seemed to think he was handsome. He had black hair that was parted on the left, a clear part like a furrow front to back, the hair on top brushed across his forehead like an overhang. Almost everybody who had hair and worked in business seemed to wear their hair this way. His arms and legs looked as if it were possible that they had once been muscular. They weren’t flabby, really, just soft, without definition. He had a paunch. He didn’t look pregnant—nothing like that—but it did look like he could have hidden an entire roast chicken in his stomach. I think of me looking at him then, the alien that he was to me, this strange aged life-form, ancient as a fossil. But he was only forty-three years old at the time.

He flipped through a couple of pages looking for a word or two that would be worth reading. He settled on a passage and read it aloud.

“‘When a Tralfamadorian sees a corpse . . .” He trailed off. The rest he read to himself, increasingly bewildered, as if reading badly written directions for building a periscope.

He shook his head, took off his glasses, and tossed the book gently back to me, like a frisbee. “Seriously? What’s great about that?”

I shrugged. I didn’t know or couldn’t answer or didn’t care. Maybe it wasn’t great. But I loved reading Vonnegut and his playful, witty snark, his fearless simplicity.

“The real world,” he went on. “I like to read about the real world. It’s so typical of this generation—”

He stopped himself before the coming diatribe, the one he used with my sisters but hardly ever with me. My two sisters—eighteen and twenty-one at the time—were authentic hippies, the kind you see in grainy footage now, dancing in the rain and mud listening to their crazy kid music on psychedelic drugs. They wore bell-bottoms and tie-dyed T-shirts, and all of their boyfriends had long hair and no ambition whatsoever to be or do anything. My father and sisters found their way into the generational arguments common in those days, about Vietnam and imperialism and drugs and women’s rights. Shouting ensued. My father and I didn’t tangle much because I didn’t express a point of view; I don’t think I had one. Could this frivolous sentence in Slaughterhouse-Five be the perfect opportunity for an early-morning fight? Perhaps, but he let it slide. He had bigger fish to fry.

“You know what?” he said. “I’ve got a book for you. I read it when I was about your age and I loved it. It’s actually one of my favorite books.”

“Really?”

Not what I expected. I was surprised at the offer and even interested. Though my father and I weren’t always on the same wavelength and his long absences and brief appearances at home turned him into something like an odd recurring character on a sitcom, I missed him in a way that felt preprogrammed, genetic. I did want to have a relationship with him, if at all possible, I was just never sure how to go about getting it. This felt like an opportunity to do that.

“What is it?”

“It’s called Kim. It’s by Rudyard Kipling.”

“By what?”

“You’ve never heard of Rudyard Kipling?”

“No,” I said. “Is that even a real name?”

He was still smoking that cigarette. Maybe it was his second cigarette. In my memory, when I conjure his face, it’s always filtered through a smoky ether, like the movie version of a dream.

“Yes, it’s a real name,” he said.

I gave him an opportunity to pitch me. “What’s it about?”

He thought about it. “Well, it’s about a boy, right around your age, I think. In India. It’s got character and history and spying and he’s—well—I don’t want to spoil it. I gave a copy to your sisters a few years ago, but I think it’s more of a guy story. I’ll pick up a new copy on the way home. Read it, and then we can talk about it. What do you say?”

He smiled a real smile (something we didn’t see that often) and I could tell that this was something he really wanted me to do. I said that sounded like a good idea.

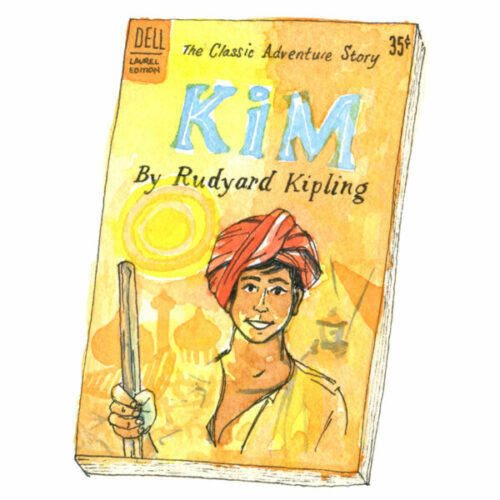

After everything that happens in this story (and everything that doesn’t happen), I wish I could blame him for offering up this dud—Kim, by Rudyard Kipling. But my father was not alone in loving this book. Lots of boys grew up reading it, and perhaps still do. On Amazon, you can choose from twenty-five different editions of Kim. A movie was made from it starring Errol Flynn. In 1998, the Modern Library ranked Kim number seventy-eight on its list of the one hundred best English-language novels of the twentieth century, right between Finnegans Wake and A Room With a View. And according to Charles McGrath in his review of If: The Untold Story of Kipling’s American Years by Christopher Benfey, it was “practically a handbook for CIA agents in Southeast Asia in the nineteen-fifties and sixties. Allen Dulles, the head of the agency, kept a copy at his bedside, and Edward Lansdale, the chief architect of the early American strategy in Vietnam, urged all his operatives to read it and pay special attention to Kim’s ‘counterintelligence training in awareness of illusions.’”

To be fair to me, however, the synopsis on the back cover does not make it sound quite that swashbuckling. “Kipling’s last major work about India, a farewell look brimming with all the color and sound, squalor and splendor of that exotic land. Kim, the orphaned son of an Irish soldier, is a mischievous worldly imp growing up in the walled city of Lahore . . .”

It goes on to say that the story is set after the Second Afghan War, which ended in 1881, but before the Third, probably in the period 1893 to 1898.

Between the Second and the Third? Say no more, I’m hooked! What fourteen-year-old boy in Alabama wouldn’t be?

Which is to say I approached the book warily. I do think books can be judged in part by their covers, and that’s why authors and publishers try to pick just the right one. The edition of Kim my father gave me that evening had the drawing of a boy with a winning smile in traditional turban headdress holding a stick. It was hard to tell whether the boy was meant to be white or brown, or if Kim was, in fact, a boy at all. He was definitely a mischievous imp!

Now, take the cover of Slaughterhouse-Five: it was bright and fun and modern, and all the words on it were printed in rare fonts that had only recently been invented. Kim, by contrast, looked like it had been made from secondhand public domain materials from somewhere between the Second and Third Afghan Wars. Didn’t book designers at Dell know it was almost 1975? Or was this the best you could get for thirty-five cents?

That was, admittedly, a superficial take. I needed to get into the meat of the book itself before making any judgments. Begin at the beginning. The very first lines of a book are so important. They’re an invitation into an imaginary world where for hours, days, maybe even weeks you are being asked to live.

This is not the first but the first half-sentence of Kim: “He sat, in defiance of municipal orders, astride the gun Zam-Zammah on her brick platform opposite the old Ajaib-Gher—” Okay. I have to admit it: I was lost. I have to say that even now, as I read and transcribe it for this story, I am still lost, hopelessly, in a world of Zam-Zammahs and Ajaib-Ghers. What kind of crazy town was I being asked by my father to enter? I read the rest of the first paragraph and it could not have been more off-putting had it been formulated in a laboratory for expressly that purpose. I thumbed ahead and page by page there was more of the same for the next 250 pages, tense, turgid, buttoned-up English prose about a boy, a time, and a place I did not and could not be made to care about at all.

Here are the very first lines of Slaughterhouse-Five (number eighteen on the Modern Library list, by the way!): “All this happened, more or less. The war parts are pretty much true. One guy I really knew was shot in Dresden for taking a teapot that wasn’t his. Another guy I knew really did threaten to have his personal enemies killed by hired gunmen after the war. And so on. I’ve changed all the names.” Oh, Mr. Vonnegut! You want me to go to Dresden with you while it’s being bombed to bits during World War II, and there witness terrible pointless death and destruction? Of course I will. Of course.

I did go to Dresden with him: he took me there with his book. I went other places with Kurt Vonnegut as well in his other books, even Tralfamadore. But I never made it far into India with Mr. Kipling. Maybe four pages? Every few weeks on his return from the real world my father would ask me how the book was coming along and I would I tell him, “I’m just getting into it,” and then, “It’s a little hard to get into,” and then “I can’t get into it, Dad. I’m sorry.”

He gave me his disappointed hang-dog death stare (he had variations and gradations on the death stare) and shook his head. He knew I would not read Kim that summer. I knew it, too. But I kept it on the bookshelf anyway, not far from Shakespeare.

Time passed. My father came and went, appearing and disappearing. California, New York, Paris, Nagoya. He always brought back a little trinket, something to prove he had been somewhere and that he had thought of us while he was.

Finally, Christmas came. Wonderful Christmas. Surely this was the best day of the year. Christmas morning our living room was overflowing with gifts, full of everything we’d asked for, mentioned, pointed at or dreamed of wanting through the course of the year. I think my mother kept a list, which she began on December 26 and kept with her, like a dogged reporter on the heels of a story. It was ridiculous and obscene, the number of presents we received, but not in a way any of us objected to. My sisters and I left the room loaded down with marvelous things, but now, forty-something years later, I don’t remember any of them.

Except for one.

Almost lost beneath the wreckage of wrapping paper was the last present with my name on it—a book, I could tell just by looking. I opened it.

It was another copy of Kim.

Surely you have read this by now, my father had inscribed it. Merry Xmas, I love you, Daddy.

We both got a good laugh out of that. That was the mystery of my father: his searing disappointment often flowered into a playful wackiness. The problem was you would never know which one you were getting until you got it.

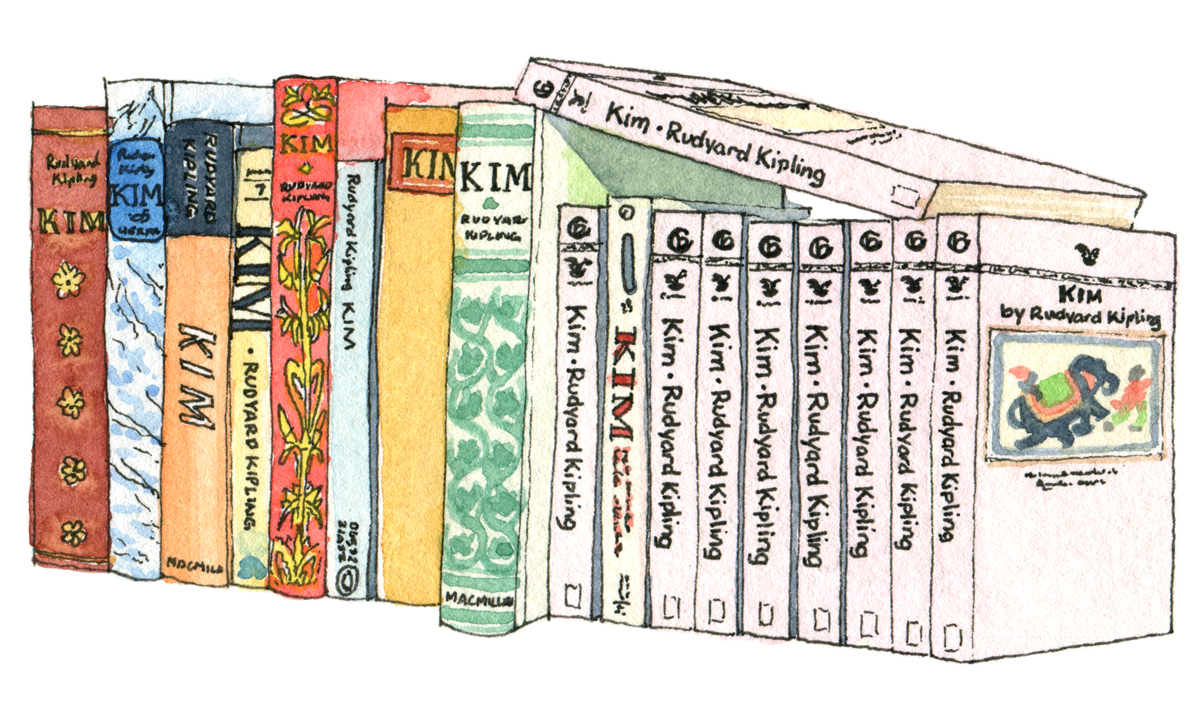

And this is how the deluge of Kim began. From Christmas 1973 on, until his next to last Christmas in 1995, my father gave me a copy of Kim. Each had its own clever inscription: Don’t read this, buy the CliffsNotes. And, Dear Daniel, Do you think this book will ever catch on? All of them playful, without a touch of malice. I don’t have every Kim he gave me; over the years I’ve had to let many of them go. Today I only have nine out of the twenty-one he must have given me, once a year, year after year after year.

But I wouldn’t read it no matter how many copies he gave me, because it just wasn’t my style. Or maybe I wouldn’t read it because he was so relentless. Reading the book would have undermined the tradition of not reading it. It would destroy these annual opportunities we had to celebrate his hopes for me and my determined efforts not to fulfill them, as would happen so often through the rest of our lives together. The book was an encapsulation of our relationship, in paperback. The joke was such a hit with me that he started giving extra copies to my sisters as well. He slipped hundred-dollar bills into every copy, often three or four. When my son Henry was born, in 1993, he gave one to him. This is the first of many, he wrote. True to his word, Henry got another one the next year—Your second Christmas, your second copy of Kim. Treasure it, lad—treasure it. And for his third Christmas, in 1995: Dear Henry, Someday you will thank me for this abundant literary gift. I love you, Grandad.

Henry never thanked him. He hasn’t read the book and doesn’t even know he ever got one, much less three of them, unless somehow by accident he reads this essay; like me, not a big reader. My older sister Rangeley’s first child, Dan, also got three or four, which he never read either.

During his lifetime, my father must have purchased over a hundred copies of Kim.

I don’t believe my father realized how important these books would become in his mythology. I’m sure he thought of them as a recurring joke stuffed with cash and not much more than that. And that would have been enough.

But then came the braids.

The interior of cigarette packs are lined with a thin layer of aluminum foil to protect the contents from moisture and as a membrane to keep the cigarettes fresh. During the heady days and nights when you could smoke anywhere and everywhere, my father was never without a cigarette—at home, in the car, at the office, by the pool, on the beach. This was a lot of cigarettes, sometimes three packs a day. When he came to the end of a pack he would remove the inner foil from it and while he was on the telephone (which he was on for hours every day) he’d tear the foil into strips, twist them, and braid the strips together into something resembling a silver macramé belt perfect for a squirrel wearing cargo pants. He made hundreds of these braids a year and many of them found their way into the pages of Kim.

Now, in addition to the Ben Franklins secreted like luxurious bookmarks scattered throughout Kim’s impish adventure, we’d have these tinfoil braids. Four or five in each book. When his production output doubled and then tripled, far beyond the capacity a paperback book could handle, the kids would get paper lunch bags full of them, under the tree with the rest of our presents. (He never gave my mother a bag of his braids, and he never gave her a copy of Kim, and they were divorced in 1982.) It’s impossible to say how many braids like this I received over the years, but I would guess at least five hundred, maybe more, my sisters the same. I know he gave them as presents to other people, too. My father did not draw or paint or write or build treehouses, make ships in a bottle, or collect Lincoln pennies. Other than a sprawling international import-export business, the only objet d’art he ever made were these braids. “This is my art,” he said, somehow joking around but being entirely serious at the same time.

Reading books—or, really, not reading them—was the slender thread that attached us to each other, and books are what finally cut it. After college I worked with him for a few years, but when he wanted me to throw my hand in with him for the long haul I declined. I told him I wanted to write instead. “That’s rich,” he said. “Whoever told you you could write?” Then, trying to soften the stab, “If you want to write, write invoices!”

But I had tried writing invoices and wasn’t very good at it. I moved to Chapel Hill, North Carolina. I saw my father infrequently after that, maybe once or twice a year. Occasionally he would call with book recommendations for his writer son: Shogun, The Godfather, Lonesome Dove. I loved Lonesome Dove.

I wrote a book of my own and sent it to him. I’m not sure which one it was. I wrote so many books so quickly when I was young, and so poorly. All remain blessedly unpublished.

I waited, but I didn’t hear from him.

Then in 1984 I was in New York City, and my father came through town. I was twenty-five. We went out to dinner—sushi, sake, lots of both—and then to his hotel room at the Sherry-Netherland for a nightcap. It had been, so far, a lovely evening, but when he got back to his room his eyes narrowed into a variation of the stare. It was time to for him to make his judgment.

“So,” he said. “You’re not exactly setting the world on fire.”

He meant that in the years since I’d stopped working for him, I hadn’t published even a tiny morsel of my writing. I shrugged. I wasn’t setting the world on fire. If the world was on fire, it wasn’t my fault.

“I read your book,” he said, lugubriously.

This shocked me. He hadn’t mentioned it all through dinner. “You did?”

“Well, I read into it,” he said. “Enough to get the idea.”

I nodded. “I see.”

He lit up—what was he smoking then? Mores? Benson & Hedges?—and shook his head. There were little silver tinfoil braids all over the hotel room. “Why don’t you write a bestseller?”

“What?”

He was a little drunk, so he paused to find the right words. “You write—you write well, you really do. But it’s a little too . . . flowery, I think. It’s hard to really get into. If you wrote more simply, I think, more directly, had more action in it, you might write something someone would want to buy.”

He laughed, I laughed. He was trying to be encouraging.

“That would be nice,” I said.

“I mean . . .” He looked around the room for something and found it. “Like this.”

He handed it to me. It was a book called The Aquitaine Progression by Robert Ludlum. I had heard of Robert Ludlum. He’d written the Bourne series and a billion other megasellers.

“Do you know how many books this guy sells? Huge numbers. He writes one a year and they’re pretty good. I mean, don’t get me wrong: he’s not Shakespeare. But he writes stories people want to read, and that’s the idea, isn’t it? To write a book someone wants to read, the more readers the better?”

“Yes.” That was the idea, actually.

“So?”

Had I not also been a little drunk I wouldn’t have gone for the bait he dangled, tantalizing as it was. What a master fisherman he was!

“Dad,” I said, “if I could write that book, a book like that, I would. I’d love to write a bestseller. But I can’t write that kind of book. I couldn’t even if I tried. For better or worse, I’m stuck writing the kind of stuff I write. My flowery, hard-to-get-into stuff.”

I laughed a little but he didn’t. The atmosphere in the room had suddenly changed, the air thinner, harder to breathe. His eyes narrowed: it was the mother of all death stares.

“You think you’re better than he is, don’t you?”

I didn’t answer, and I didn’t answer for a beat too long.

“No,” I said. “I don’t think I’m better. I don’t think it’s a question of that. I’m just different. We just write differently, and maybe we’re drawn to dissimilar . . . ideas. And styles.”

But he wasn’t having any of it. He had my number.

“You do think you’re better,” he said.

I shook my head and insisted that I thought no such thing. But the truth is, I did think I was better. I thought I would jump off a cliff if the only book I could write was The Aquitaine Progression. I’d rather be writing invoices. That I would have the temerity to think I was a better writer than Robert Ludlum, after not having published a single word—and honestly, not having read a single word of Robert Ludlum either—it was too much for him, as well it might have been.

“Okay, big shot,” he said. “If he’s so bad, name two books that are better. Name two books that are better than the books he writes.”

I didn’t have to think very long.

“Off the top of my head?” I said. “The Bible and the telephone book.” This was the first time in my life, and possibly my last, when on the spur of the moment I produced the perfect riposte.

He exploded.

“Get out! Get the hell out.”

I’d heard him yell like this at my sisters in the living room after a long night of drinking and politics, but I was unseen then, at the top of the stairs, listening. He had never raised his voice like this to me. His cheeks blazed red but the death stare was gone. Now he looked sad and scared, as if I were the one attacking him.

“Look, Dad—”

“No, you look. Go. Just go. Now.”

He stood up and so did I. I walked toward the door and he was right behind me all the way. I slowed down a bit and waited on a hug, a head rub, an air kiss—anything vaguely conciliatory. But nothing came. He was serious: he wanted me gone, out of his sight. All because of Robert Ludlum? Well, no. Because he hadn’t really heard me saying I was better than Robert Ludlum. He heard me saying I was better than him, too.

I opened the door and as soon as my body had passed through the frame he closed it, and that was the last time we spoke for quite a while.

The last copy of Kim I ever got from my father was in 1995. This one read, Having created a classic supply and demand situation, this copy of Kim is now worth 700 zillion dollars. Merry Xmas, I love you.

The next Christmas was his last; he would die in March 1997 of heart arrythmia after quadruple bypass surgery. Maybe he sent one to me in 1996 and I lost it, or gave it away, or took it to the thrift shop, or sold it for a quarter in a yard sale. I prefer to believe he never sent one, that the clogged arteries that ultimately killed him had thrown him off his axis, and the smaller things—Kim and his seemingly infinite supply of tinfoil braids—dimmed in importance.

After the night in the Sherry-Netherland, I kept writing. Over the next twelve years I wrote three, four, five novels, and then a collection of short stories, none of which I sent to him. Good thing, too: they were awful. I worked in bookstores, had other part-time jobs, was just getting by, but he sent me money if I asked for it. He admired my work ethic, if not my work, even though it seemed odd to him—as it did to me, in fact—that I would fail at one thing for such a long time and not turn my attentions elsewhere. When he died I was finishing what would turn out to be my first published novel, about a father whose son is trying to get to know him before he dies. He never had a chance to read a word of it, but without his help—his financial help, of course, but more crucially providing the subject matter that would consume me for years—I never would have written it at all.

My father wasn’t much on things. He had some lovely homes, but not much inside of them was truly his; they were decorated by tasteful designers. Even the bulk of his library was a selection of books amassed by a decorator because they looked good on a shelf. He didn’t care. That sort of thing didn’t matter to him. He was always working, always scheming. His homes were merely comfortable places to work and think and eat and drink and laugh and argue with people and listen to Sinatra, Count Basie, Tony Bennett. When he died his houses were swallowed up in secret business dealings and a second marriage. No pocket watch, no family heirloom to hand down to me. All I have of him now are these books, and the gold and silver cigarette braids—his art. Hundreds of them. As I’m writing this, he’s been dead for twenty-five years. I don’t miss him anymore, but the mystery of his absence persists. I’m just a few years from equaling his short life now. I can see the nine of copies of Kim on the bookshelf from the chair where I’m writing. Sometimes I think that if he had hung around a little bit longer, and his heart had softened with age instead of been blown to smithereens, all the Sturm und Drang of our past mere bygones and a true friendship between us flowered—if he had been able to give me just a few more years of his life—maybe I would have gotten around to reading Kim. But I know that’s not true. He would have been so pleased, though, had I made it through the Zam-Zammahs and Ajaib-Ghers to the heart of the story, whatever the heart of it is. But I never wanted to please him: I wanted him to be pleased by me.

Daniel Wallace is author of six novels, including Big Fish (1998), Ray in Reverse (2000), The Watermelon King (2003), Mr. Sebastian and the Negro Magician (2007), The Kings and Queens of Roam (2013), and Extraordinary Adventures (May 2017). His first book of nonfiction, This Isn’t Going to End Well, is out April 2023.