“Sojourning is a daring act of freedom-making and . . . an acknowledgment of reclamation of spaces where Black women and femme folks were historically excluded.”

I’m in Edenton, North Carolina. I’m here to do some sacred work. I slowly turn the bowl of white rose petals in my hands. They are moist from freshly fallen tears after hearing Lois Deloatch sing “It Is Well with My Soul.” That was my Nana’s favorite song, and it still broke me to hear it. It was approaching the two-year anniversary of Nana’s death and her entering the ancestral realm. I turn the bowl again and look out at the water next to Molly Horniblow’s resting place. Horniblow hid her granddaughter Harriet Jacobs in her attic for nearly seven years to protect her from the oppressions of slavery. Harriet Ann Jacobs was a freedom fighter, writer, and businesswoman and the author of the exceptional and heart-wrenching autobiography Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861). There’s something special about a grandmother’s love and protection. Hot tears fell as our grandmothers’ loves overlapped.

It is well with their souls, and mine is working on it. I throw petals into the water. Prayers, blessings, tears. Prayers, blessings, release. A hand gently supports my lower back. I breathe out and let go of the rest of my flower petals. A duck swims by, head high, slowing down enough to watch our ritual of love and attention to the ancestors and grandmothers. She wades through the flowers like they belong to her.

Asé.

I stood in front of a True Value hardware store. The two-story brick building sported a sign and an unremarkable concrete parking lot with an equally unremarkable wooden fence. Or so I thought.

The site was where Molly Horniblow’s house once stood. “Had the least suspicion rested on my grandmother’s house, it would have burned to the ground,” Jacobs wrote. “But it was the last place they thought of. Yet there was no place where slavery existed that could have afforded me so good a place of concealment.” I just couldn’t imagine how Jacobs endured such a daunting space. The stifling lack of movement of her body and the air, the vermin that crawled on and around her, and the rigidity of the wooden garret that refused to bow to the world rotating around it had to be a Herculean task. Her concealment was life and death. Her grandmother’s and her family’s love also hid her and sustained her through the ordeal.1

Now, there was no concealment, just tar, brick, and memory. “Chiiiiiile …” I sighed. How could such a spectacular act of resistance be physically erased?

Michelle Lanier, director of the North Carolina Division of State Historic Sites, called for my touring group’s attention as she stood by the wooden fence in a hand-dyed indigo dress. Lanier’s presence is commanding but not daunting. She got a calling on her. Lanier nimbly addressed our disappointment that Jacobs’s hiding place no longer existed in the physical realm. She smiled and urged us closer to her and into her world-making, pointing to a small hole in the fence. She challenged us to think of the hole in the fence as similar to the gimlet-drilled holes Jacobs made herself in the same spot where the fence stood. Each hole represented a possibility of promise for Jacobs to see the world and, perhaps most longingly, her children. Each drilled hole was an adamant and intentional choice to fight back against her oppression, a chance to claim her autonomy.

The overlap of worlds, both spiritual and physical, past and present, was a powerful excursion of imagination and will. Lanier’s encouragement to reimagine the hole in the fence was an exercise in what she coined “womanist cartography,” the “recenter[ing] of Black women and femmes by rendering our narratives visible, audible, legible, and autonomous.” Through Lanier’s guidance, I recognized the fence hole as a reincarnation of Jacobs’s “Loophole of Retreat.” This act of ancestral restoration will sit in my spirit for years to come. As Koritha Mitchell writes about a similar experience with the True Value fence, “Engaging landscapes while telling Black women’s stories inevitably shifts one’s encounters with a location. This practice of restoring memories honors those whose humanity is denied whenever their experiences are disregarded … when we use our own storytelling capacity to engage those usually erased, our humanity is restored along with theirs.”2

My pilgrimage to Edenton was due to my participation in The Harriet Jacobs Project’s inaugural Harriet Jacobs excursion, spearheaded by Michelle Lanier and Johnica Rivers. I was part of a dazzling cohort of seventy Black women who are the spiritual descendants of Jacobs and countless other ancestral Black women known and unknown. As we gathered in the beautiful Umstead Hotel the night before our Edenton visit, we embraced the idea that we were ancestral seeds of hope and promise, Jacobs’s wildest dreams realized. We were a temporary community of Black women bound together by the permanent practice of imagination and reclamation of Black women’s stories and spaces. In describing Rivers’s curatorial debut of Letitia Huckaby’s breathtaking photo installation “Memorable Proof,” Lanier stated, “Black South women’s stories held by and centered in Black South women is a powerful thing.” An homage to the Fannie A. Parker Woman’s Club in Edenton, “Memorable Proof” is currently installed in the historic Chowan County Courthouse where Molly Horniblow organized her emittance from slavery. As Huckaby states in her conversation with Jessica Lynne in this issue, “I really am a bit of a storyteller, but just instead of writing it all down, I use images. … I’m invested in lacing Black history into a contemporary experience.”

The South, a region often overshadowed by its past, is also a space where storytelling and place run in tandem with history. During my time with my fellow sojourners, I thought extensively and deeply about southern Black storytelling, history, and archive, the oral tradition often being the sole space where certain people and memories can exist and even thrive. Jacobs’s storytelling sustained her—and it sustains us, her cultural progeny, and encourages us to continue to tell her stories and the stories of countless other ancestors, to create new southern worlds and resurrect and reclaim others.

What I take away from my trip to Edenton and this issue of Southern Cultures is sojourning as an act of radical (re)imagination of oneself and the space the self takes up in the world. We are indebted not only to Harriet Jacobs’s vision for a future of her own making but also to the incredible work of our guest editors Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Michelle Lanier, and Johnica Rivers for calling attention to and paying homage to Jacobs’s truth and our own. Sojourning is a daring act of freedom-making and, if we lean into Lanier’s theorization of “womanist cartography,” an acknowledgment of reclamation of spaces where Black women and femme folks were historically excluded. Harriet Jacobs’s time in her grandmother’s attic gave her space to radically imagine herself free. Jacobs’s imagining and writing left an indelible mark on generations of sojourners, myself included.

Regina N. Bradley is a writer and researcher of contemporary black life and culture in the American South. She is the author of Boondock Kollage: Stories from the Hip Hop South. She is an alumna Nasir Jones HipHop Fellow at Harvard University and an Assistant Professor of English and African Diaspora Studies at Kennesaw State University. She can be reached at redclayscholar.com.

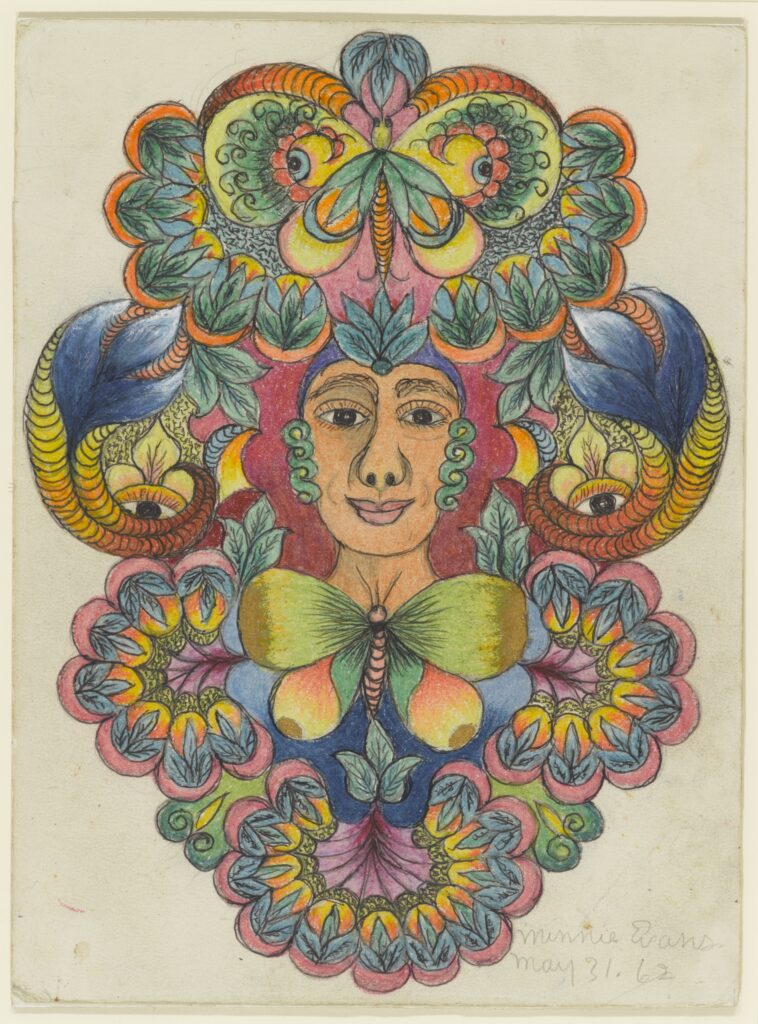

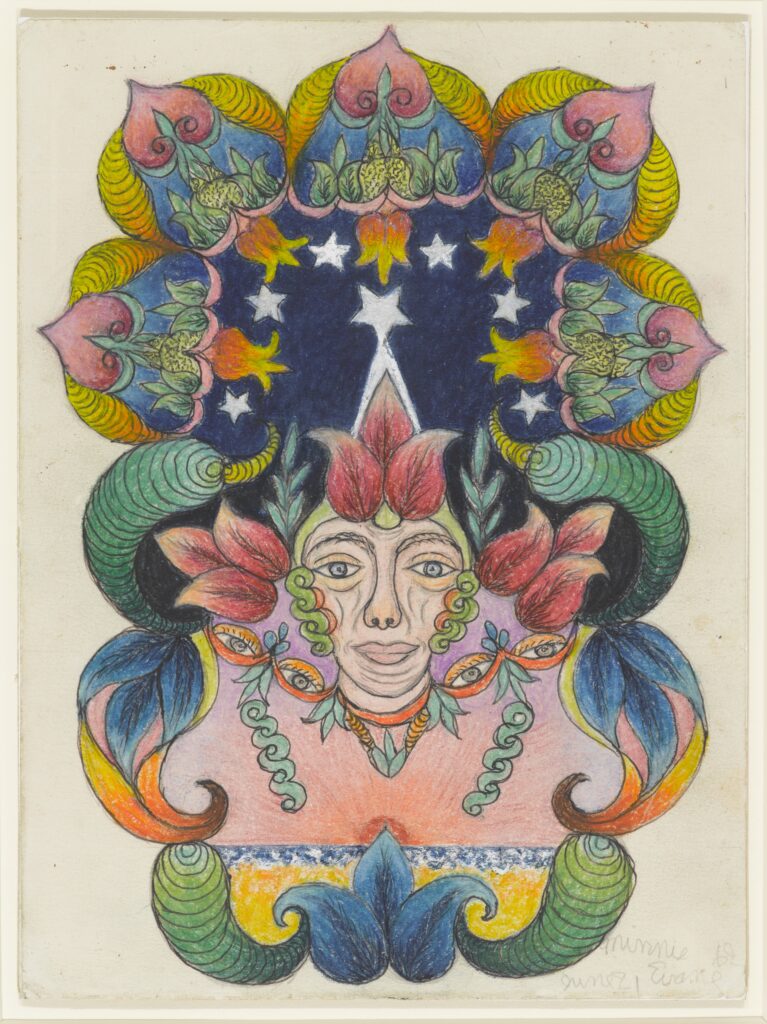

Header image: Untitled, by Minnie Evans, 1960. Colored pencil on paper, 11 3/4 × 8 3/4 in. North Carolina Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. D. H. McCollough and the North Carolina State Art Society (Robert F. P. Phifer Bequest, 87.2).

NOTES

- Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861), ed. Koritha Mitchell (Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press, 2023), 179.

- Michelle Lanier, “Rooted: Black Women, Southern Memory, and Womanist Cartographies,” Southern Cultures 26, no. 2 (Summer 2020): 20; Koritha Mitchell, “I Was Determined to Remember: Harriet Jacobs and the Corporeality of Slavery’s Legacies,” Los Angeles Review of Books, May 30, 2023, https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/i-was-determined-to-remember-harriet-jacobs-and-the-corporeality-of-slaverys-legacies/.