I.

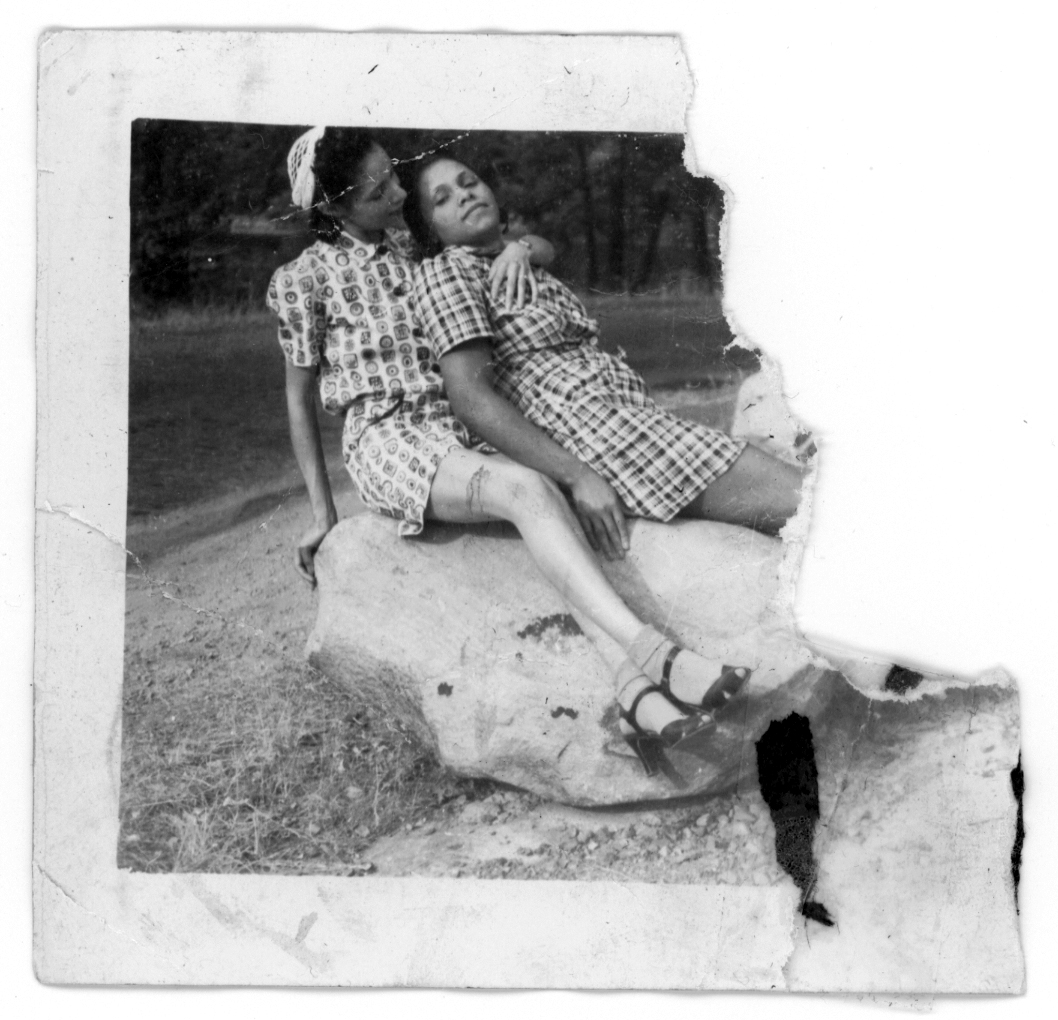

I have carried a photograph on my person for the past year now. Like my debit card, lip balm, or driver’s license, this photograph has become part of my daily essentials kit. In the black-and-white image, two women clad in patterned and madras print dresses and low kitten heels sit on a rock and embrace casually yet lovingly. One woman rests against the chest of the other, wrapped in the arms of her companion. The woman who is held gazes directly and assuredly at the camera. The other woman looks softly at her companion. It is as if they have been preparing for this moment of capture. Here is the sun, they might have said. It’s best for us to sit this way. You are almost there. A friend, a loved one, a sister, or an aunt steadying their hands on the camera.

The two women wear the expressions of people who know one another well. They hold one another’s secrets. They have been lost in winding conversation on a leisurely afternoon. They have just finished a walk through the park. They have joined friends for a gathering or celebration. They have come to this afternoon prepared to immortalize their intimacy. This photograph is not dated nor is there any indication of location or who these women might be. Behind them, an expanse of land. Perhaps a path or a picnic area. I cling to this photograph.

One year ago, in New Orleans, this photograph, whose subjects I do not know, found me. The Material Life store is a New Orleans staple and a Seventh Ward gem. When the brick-and-mortar was still on Bayou Road (it has relocated temporarily to the Contemporary Arts Center of New Orleans), a back wall of the store was covered in Black vintage pinup magazines from the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s. I have found old copies of Jet magazine, a German children’s book about Josephine Baker, and an “I Love Dykes” pin I gifted to a person I once loved. You would enter the front door, and, more often than not, be greeted by Carla Williams herself, acclaimed photographer, art historian, and owner of the shop. Carla is an archivist of Black life and culture, and her store contains some of the most delightful, interesting, and unique ephemera that you never knew you needed. When I was last in the store, I happened upon Carla as she was cataloging a newly arrived batch of found photographs.

On top of a pile of what might have been hundreds of images was the photograph of the two young women. Carla sold it to me for ten dollars and I knew then that I would never spend a better ten dollars. I found this photograph during a period of reckoning as I embarked on a journey to parts of Europe and North Africa and throughout the United States for the better part of eighteen months, trying to figure out how to return home, how to return South. For a while, I carried the photograph in my passport holder, almost as if to say to any official reviewing my documents: This image speaks to a part of who I am. How I have found myself in the world these days. How I want to show up consistently as I move across bodies of water and swaths of land. I held onto the photograph because, deep down, it reminded me of the touch and gaze and comfort I was missing so far away from my own lover.

One afternoon, months after my departure from New Orleans, I was at the public library in Hampton, Virginia, writing. As I packed up my belongings for the day, I opened the small clutch where I kept the photograph only to find that it was not there. In some absent-minded flurry I must have dropped it inside my backpack, I told myself. I emptied my bag onto the desk and out tumbled pencils, three different books, a water bottle, hand lotion, a camera, everything but the photograph. I recounted my steps: grandma’s house, mechanic’s shop, grocery store, back to grandma’s, the library. It would be inaccurate to describe my feelings as panic. Instead, I felt a kind of sad, gaping hole beginning to emerge inside me, like the kind that would form whenever I lost a cherished toy as a little girl, one that had become a kind of appendage. The image had become data, a vernacular photograph that visibly marked intimacies between Black women. I looked at and listened to this image, to borrow loosely from the thesis of scholar Tina Campt’s text Listening to Images, as I navigated my own Black southern politic. How could it disappear before I had completed my reckoning?1

I sat down at my workstation and cautiously leafed through my books. There, squeezed between two pages of Joanne Braxton’s Black Women Writing Autobiography, was the photograph. How interesting, I said aloud to no one. (Months later, a loved one’s dog would chew the photograph in half.) Of course, I don’t remember placing it there, and yet perhaps I was using it as a bookmark to remind myself of my own folds and crevices, of the things I have known about myself even when I did not have a language for them, of how to name myself. Indeed, isn’t one task of autobiography the task of naming ourselves?

“Then you must tell ’em dat love ain’t somethin’ lak uh grindstone dat’s de same thing everywhere and do de same thing tuh everything it touch,” Janie begins to tell her best friend Pheoby at the end of Zora Neale Hurston’s pioneering novel Their Eyes Were Watching God. She continues, “Love is lak da sea. It’s uh moving thing, but still and all, it takes shape from de shore it meets, and it’s different with every shore.” This declaration looms over me.2

As part of my journey, I am reading closely about the lives of Black southern women who love women in order to think through the myriad of ways love manifests itself in my life. More than this, though, I am learning how to name my own discomforts, pleasures, and desires in an effort to fully see myself: Black, Southern, Queer.

I carried the photograph in my passport holder, almost as if to say to any official reviewing my documents: This image speaks to a part of who I am.

II.

Within the papers of the late artist and architect Amaza Lee Meredith is a series of photographs that unveil more of who she was to me each time I encounter them. This word has stuck in my chest: unveil. To unveil something is to imply that it has been covered. To unveil is to make known. We can only know ancestors but so well, I suppose. This is to say, I think they have left for us what they desired we would find and, maybe, if we pay close enough attention, this is all the material we need to imagine them fully.

From 1935 to 1958, Meredith served as founding director of the art department at Virginia State University (VSU) in Petersburg, Virginia. I am struck by the meticulousness with which she kept her personal records, no doubt the result of her fastidiousness as an educator responsible for a college department and students. Her archives are full of photographs from family vacations, award nominations, travel brochures, correspondences with colleagues and other academicians, church bulletins, fliers, and advertisements for local community programs.

Meredith avidly researched her paternal lineage. Notes from her archives reveal details about her Scottish heritage and the Meredith family coat of arms. There are also delicately preserved photographs of Meredith and her siblings as young children. In one, the entire family is gathered in the backyard. At the far right of the image is Meredith’s mother, Emma P. Kenny-Meredith, a strikingly beautiful Black woman whose poise radiates. On the far left stands Samuel P. Meredith, Meredith’s white father. Here, an interracial family in the early twentieth century posing to concretize themselves amid a legal framework that did not offer them a language to do so. Many of Meredith’s images are labeled in her own handwriting: date, location, persons present. The images she has saved for those of us who encounter them after her death speak volumes. This is what it means to self-fashion, to refuse an erasure that threatens the abundant, complex visualization of Black southern women.3

Meredith’s archive is filled with letters. There are letters written to her students; those written to other artists and educators; exchanges from friends who requested her design and architectural expertise; and a large portion addressed to family members, especially her sister, Maude K. Terry, in New York. In almost all the letters, especially those written by loved ones, the signatory closed their note with a cheerful greeting to Meredith and Dr. Colson, or “Dr. C,” or, simply, “Edna.” Dr. Edna Meade Colson is the person with whom Meredith spent her adult life.

This word has stuck in my chest: unveil. To unveil something is to imply that it has been covered. To unveil is to make known.

Meredith was born in Lynchburg, Virginia, in 1895, the youngest of Emma and Samuel’s four children. Before her professorial tenure at Virginia Normal and Industrial Institute (now VSU), Meredith was first a student at the university. In 1926, she would go on to earn a bachelor’s degree in fine arts from Teacher’s College at Columbia University, followed by a master’s degree in art education in 1934. But it was while enrolled at Virginia Normal and Industrial pursuing a teaching certificate (awarded in 1922) that she met Colson, who was seven years Meredith’s senior. A fellow Lynchburg native, born in 1888, Colson would become a prominent supporter of access to higher education for Black students in Virginia as well as voter enfranchisement movements in the state. Architectural historian Jacqueline Taylor posits that Meredith’s and Colson’s relationship may have begun as early as 1915, situating their friendship and partnership within a context of changing public notions of womanhood in the twentieth century. According to Taylor, both women “developed a new sense of self as they spent increasing amounts of time testing their independence and self-reliance while traveling away from the comfort of familiar expectations and surroundings.” Highly educated and upwardly mobile, Meredith and Colson were part of the emergent Black middle class as they traveled, taught, wrote, and organized politically. In Meredith’s work as an artist and architect (although she was never formally trained as the latter), and in Colson’s role as an educator and political organizer, the two women could be aptly labeled “race women.” They were women of a relatively privileged milieu who, Taylor asserts, refused certain conscriptions into the normative roles assigned to them as Black women.4

As I search for further imprints of Colson on Meredith’s papers, I come to a folder that contains a photograph of the two women, later in life, set against a backdrop of trees, greenery, and their carport. Colson is eighty-five, seated in a wheelchair with her clasped hands resting in her lap. A white jacket is draped over her shoulders. Her expression is stately. Standing to her left is Meredith at seventy-eight. She wears an almost startled look, although the photograph appears to be posed rather than candid. Meredith’s left hand grips the left armrest of the wheelchair as her right hand holds onto the back handle. Though they don’t smile, they are alert and attentive. A comfort lingers between the two women.5

The folder containing this photograph is dated 1973, twelve and eleven years before Colson’s and Meredith’s deaths, respectively. Ms. Meredith, Dr. Colson, let’s just get one before I leave, I won’t be back in town for a few months, I imagine a companion saying while holding the camera. It’s a plea that mimics the way I plead with the elders in my life to take photographs with me when they would prefer not to be bothered.

Meredith and Colson do not touch in the image. Perhaps they are tired or uninterested at the end of a long afternoon of hosting, which they were known to do quite often. Meredith, especially, actively kept in touch with her former art students who loved keeping her abreast of their travels, families, and thoughts about contemporaneous Black life at home and abroad. Perhaps this photograph has caught the two elders right before their evening rituals. It might not be an intrusion but rather a punctuation to a day that has been so full for two retired octogenarians.

How many photographs does one amass in the course of a life that spans almost ninety years? What intimacies have been captured between these two women who have carried one another for almost fifty of those years? What did it mean for these two Black women to choose a queer life beyond the legible frameworks for Black mobility, safety, and romantic love? What were the terms under which they named themselves?

Among the ideological scripts that Meredith and Colson tossed in pursuit of self-actualization was that of a respectable public marriage to a “good Black man.” In an outline she wrote of her life in the fall of 1980, Meredith recalled that she was once engaged to a man named Clarence. Colson, Taylor notes, was also once engaged. It is a comment that seems almost a footnote, given the depth of Meredith’s and Colson’s relationship, and yet perhaps it is something that needed to be acknowledged, as if to say: This was an expectation that did not fit me. These were not my terms.6

There is one box included in the Meredith papers that is not publicly available, although it seems this material was once made available to researchers. Taylor cites several letters between Meredith and Colson that are sourced to this no-longer-public box. In a short excerpt from a letter written by Meredith, then enrolled at Teacher’s College, to Colson back in Virginia, the artist shares updates about her coursework and sweetly offers to recreate masterpieces to be hung in Colson’s dormitory. I am curious about the current obscurity of these exchanges and will continue to ask more questions about their present-day locations and the institutional decisions that prevent me from accessing them. As a researcher, I cannot think of Meredith’s archive as complete but rather as one in an elastic state. Who has said “no” and “not anymore”?7

This was an expectation that did not fit me. These were not my terms.

As a writer, I am asking these questions from a practical standpoint. What does it mean to responsibly and imaginatively write about, in response to, or alongside the legacies of individuals who have died? In my return south, I ask these questions because what Colson and Meredith embody is an act of radical self-fashioning toward which I am compelled. In love, I spend an excessive amount of time trying to image my lover so I can return to them when they are gone, when I have lost them, when I need to remind myself that I once knew the shape of their body. How many photographs have I lost, misplaced? And when and if I find them, what do these images prove to me?

Of all the images included in Meredith’s tightly organized archive, this particular image of her and Dr. Colson, well into age, together, feels most weighted to me. It is an image of two elders who were responsible for quietly shaping an institution of higher education. It is an image of two Black women who took great measures to commit to the US South and contend with the complex sociopolitical dynamics of the place that birthed them in and throughout the first half (and then some) of the twentieth century. It is an image of two women who have spent their entire lives together and now, perhaps, are at peace with the tenure of their intimacy. I have wondered if it is appropriate to also say that this is an image of two people in love. I am hesitant because I have seen very few images of (southern) queer, gay, and lesbian elders in love. There is a magnitude that I am daring to wrap my arms around, and I am fearful because if I say that this is an image of two people in love it implies the possibility of a future for my own self with which I am not yet ready to contend, where I too could find a profound love.

Among grand notions about what romantic love must look like, almost all of it heteronormative, I stare at Meredith and Colson in awe that I have found another example of that which we are still learning to name. Maybe it is enough to know that these two Black southern women have chosen to save and protect this photograph, such that it remained in the record, such that one day I would find it. Or that one day it would find me, like the photograph of the two unnamed women that came to me in New Orleans. If I look at each photograph and listen closely, it is possible to imagine each pair as a version of the other with time marvelously compressed and then decompressed. Maybe this, then, is part of that which is Black and Queer and Southern. To be in and out of time. To be illegible to most. Our lives, captured, become their own texts, an insistent language that only becomes legible if we truly know how to see.

This essay is from the Art & Vision Issue (vol. 26, no. 2: Summer 2020).

Jessica Lynne is a writer and art critic. She is a founding editor of ARTS.BLACK, an online journal of art criticism from black perspectives. Her writing has been featured in publications such as Art in America, The Believer, BOMB Magazine, and The Nation. She is currently at work on a collection of essays about love, faith, and the American South. Jessica lives and works in coastal Virginia.NOTES

- Tina M. Campt, Listening to Images (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 26. Campt engages with a series of “quiet images,” offering a new grammar for imagining Black futurities throughout the African Diaspora. I seek to further name that which lives beyond sight and in the “sonic frequencies” of these images.

- Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God (New York: Harper Perennial Classics, 1998), 191.

- Meredith family, Amaza Lee Meredith Papers, Virginia State University, Petersburg, Virginia.

- Jacqueline Taylor, “Designing Progress: Race, Gender, and Modernism in Early Twentieth-Century America,” introduction (PhD diss., University of Virginia, 2014), 11.

- Edna Meade Colson and Amaza Lee Meredith, 1973, box 16, envelope 251, Meredith Papers.

- Letter to Dr. Myla Lyle Smith Kearse, November 1980, box 8, folder 109a, Meredith Papers; Taylor, “Designing Progress,” 27 (chap. 1).

- Taylor, “Designing Progress,” 12 (chap. 4).