“The current iteration of voter suppression that has swept across the South has been met by renewed organizing efforts that remain determined to fully restore the Voting Rights Act and secure the promise of democracy.”

The South has often served as the crucible for democracy, and in recent years, the COVID pandemic, new voting restrictions, rampant disinformation, threats to voters and election officials, and even violent attempts to overturn election results by far-right extremists have caused people across the South and the country to view the state of our democracy with fear and alarm. More than ten years after the 2013 Supreme Court decision in Shelby County v. Holder that eviscerated federal voting rights protections, the South and the country as a whole are engaged in the most important struggle for democracy since the Civil Rights Era.

In the wake of the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches and the brutal attack on protesters that came to be known as “Bloody Sunday,” President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) into law. Ratified by Congress on August 6, 1965, the VRA was one of the hallmark achievements of the Civil Rights Movement. It built on the Fifteenth Amendment, which gave Black Americans the right to vote by creating a preclearance system, mandating that states with records of discriminatory voting policies receive federal approval before implementing new election laws. “Today is a triumph for freedom as huge as any victory that has ever been won on any battlefield,” Johnson said when signing the legislation into law.1

Originally passed by Congress with overwhelming support, the VRA eliminated many of the state and local legal barriers implemented during the Jim Crow era. Prior to the VRA‘s passage, Black people endured poll taxes, literacy tests, and even physical violence by white supremacists determined to keep them from casting a ballot. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and others organized for years to register voters in Alabama, but by 1965, only 383 of the 15,000 Black residents of Dallas County, where Selma is the seat, were registered due to barriers created by the white southern power structure.2

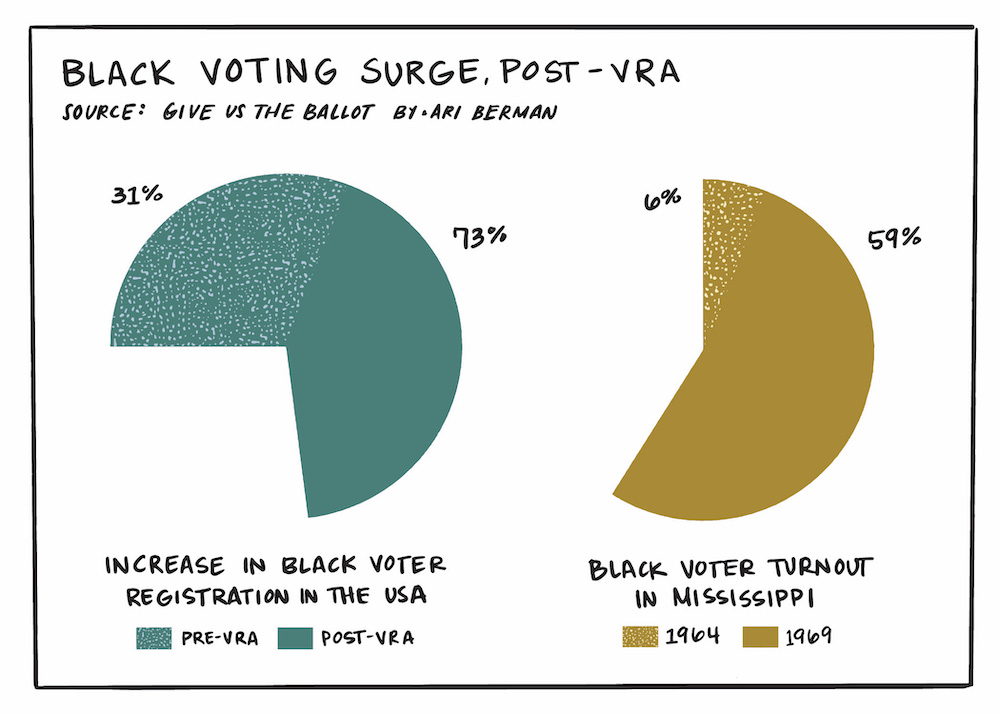

By ending these discriminatory laws, the VRA dramatically reshaped the South’s political landscape. In the decades after the law’s passage, Black voter registration in the South surged from 31 percent to 73 percent, according to Ari Berman in Give Us the Ballot. In Mississippi, voter turnout among Black citizens jumped from 6 percent in 1964 to 59 percent by 1969—an 883 percent increase in just over four years. This newfound Black electoral influence sparked a surge in Black political representation. The number of Black elected officials in the South more than doubled after the 1966 elections. As former Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote in a 1969 Supreme Court opinion in Allen v. State Board of Elections, “the Voting Rights Act was aimed at the subtle, as well as the obvious, state regulations which have the effect of denying citizens their right to vote because of their race.”3

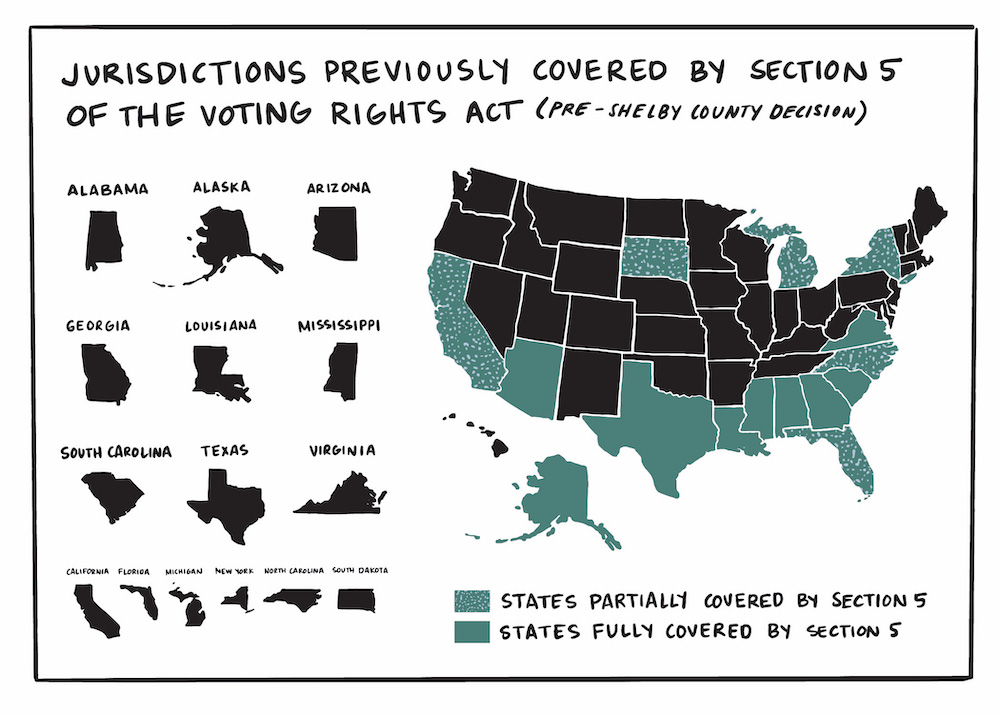

The VRA has several key provisions that serve as a buffer against discriminatory voting practices. Section 2 prohibits any voting procedure that discriminates on account of race, color, or language group, while Section 3 grants federal courts the power to suspend any voting devices it finds to have been used for racial discrimination. Section 5 established the “preclearance” mechanism, which requires states with a history of voting discrimination to provide any proposed election changes to the US Department of Justice for approval before the changes can be implemented—essentially blocking discrimination before it took place. The late Representative John Lewis, a former SNCC leader whose organizing helped secure passage of the VRA, called Section 5 the law’s “heart and soul.” Section 4 determines the formula for which jurisdictions were subject to preclearance; while that list has shifted over time, most of the states were located in the South. Historically, states like Alabama, Alaska, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Virginia were included in the jurisdictions held to be involved in blatant voting discrimination by the coverage formula. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, between 1982 and 2006, Section 5 blocked over one thousand potential discriminatory changes to voting laws across the country.4

Despite the need for and overwhelming success of the Voting Rights Act, in 2013, the US Supreme Court, in a 5–4 decision in Shelby County v. Holder, struck down the VRA’s original formula for deciding which jurisdictions were subject to preclearance or federal review of voting changes. This effectively ended preclearance requirements, excluding jurisdictions covered by a separate court order. “In 1965, the states could be divided into two groups: those with a recent history of voting tests and low voter registration and turnout, and those without those characteristics,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the majority. “Congress based its coverage formula on that distinction. Today, the nation is no longer divided along those lines, yet the Voting Rights Act continues to treat it as if it were.” The court put it to Congress to develop a new formula to determine what areas would be covered by the VRA preclearance rules, which it has failed to do for over a decade.5

Voting rights advocates denounced the court’s decision, saying it dismissed modern-day efforts to suppress voting. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg warned in her dissent that “throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.” Immediately after the decision, Republican-controlled states passed a wave of restrictive voting measures. Of the thirteen southern states, eleven passed laws to limit voting in Shelby‘s wake. Many of these proposals resembled barriers that were erected to prevent Black people from voting in the segregated South. For instance, less than two months after the ruling, the North Carolina state legislature’s Republican supermajority passed HB 589, labeled by voting rights advocates the “monster voting bill,” which was considered the country’s most restrictive because of its strict photo ID requirement, cuts to early voting, easing of rules on political spending, and other measures. The law was later found to discriminate with “surgical precision” against Black voters.6

Since Shelby, Section 2 has become the best defense against discriminatory voting policies under the VRA. This provision explicitly prohibits voting policies and practices—including redistricting proposals—that discriminate on the basis of race. Section 2 is currently the main legal defense for at least thirty federal lawsuits challenging redistricting maps throughout the country. However, Section 2 has been targeted in a series of legal cases that would further erode the VRA. In 2021, the Supreme Court weakened Section 2 in the Brnovich v. DNC court case by ruling that it can be used to strike down voting restrictions only when they put substantial and disparate burdens on voters of color. The court also considered Allen v. Milligan (formerly Merrill v. Milligan), a VRA redistricting case out of Alabama. As part of that case, the court suspended the VRA’s ban on racial gerrymandering ahead of the 2022 midterms, allowing Republican lawmakers across the South to draw redistricting lines that curbed Black voting power. But in June 2023, the high court ultimately ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, striking down Alabama’s congressional map for failing to comply with Section 2 of the VRA.7

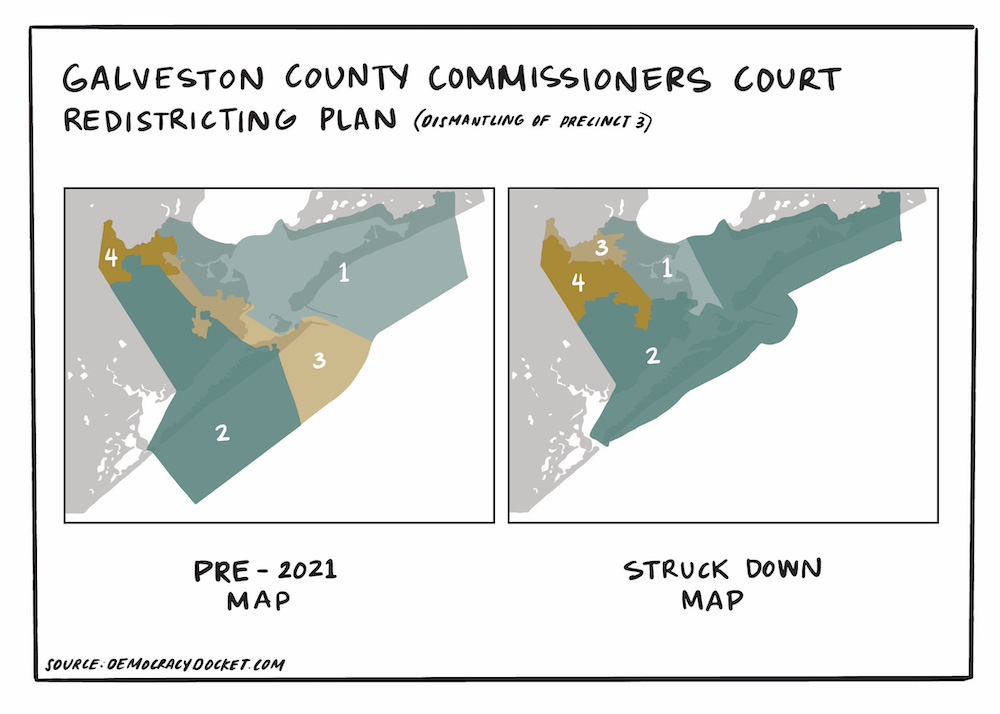

In addition, in a ruling that would further reduce the effectiveness of Section 2, a panel of federal judges in the US Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit decided in a 2–1 ruling that private plaintiffs could no longer file lawsuits under Section 2. The decision from the Eighth Circuit will likely head to the Supreme Court. More recently, the Supreme Court allowed a racially gerrymandered map to remain in place in Galveston County, Texas, for the 2024 election.8

Suppressive state voting laws have always targeted Black and other marginalized communities across the South disproportionately, but it has intensified in recent years, heightening the concerns of voting rights activists who worry that they will continue to undermine turnout in communities of color—something that has long been an issue. In 2020, more people of color turned out to vote than in any presidential election since 2012, owing to years of grassroots organizing and efforts by voting rights groups to combat restrictive policies. This trend was especially strong in the South, where an increasingly diverse electorate has a growing potential to exert more influence in regional and national politics.9

However, while turnout overall has increased due to highly contested presidential and other elections—especially since 2016—there have still been significant barriers for select communities. For example, nearly 71 percent of white voters nationally cast ballots in 2020, compared to only 58.4 percent of nonwhite voters. The rise in participation was blunted by restrictive voting policies that perpetuate racial disparities and impede voters of color. In the last decade, the US overall—and the South specifically—has become more racially diverse. According to an analysis from the US Census Bureau, in 2020, three of the ten states with the greatest diversity index are in the South: Florida, Georgia, and Texas. All three of these states are also led by Republican legislatures that have passed harsh voter suppression laws that largely impact communities of color.10

Voter suppression does not always manifest as outright denial of access to the franchise, but it can be carried out in more subtle ways that can still have a damaging impact on marginalized communities. For example, a 2020 analysis by Stanford University political science professor Jonathan Rodden of data collected by Georgia Public Broadcasting and ProPublica found that the average wait time for voters after 7 p.m. across Georgia during the June primary was only six minutes in polling places that were 90 percent white but fifty-one minutes in polling places that were 90 percent or more nonwhite.11

In recent years, significant democratic gains in the region have been quelled by failing voting infrastructure and coordinated attempts to undermine the legitimacy of the electoral process. For more than a decade, with demographic trends threatening to reduce their political influence, Republicans have engaged in a systematic campaign to spread allegations of widespread election fraud to stoke distrust in the US electoral system and to promote policies that suppress the vote to its advantage. Southern lawmakers have continued their assault by enacting discriminatory measures that undercut the ability of voters across the region to have fair and equitable access to the ballot. In 2023 alone, at least fourteen states have implemented laws making it more difficult to cast a ballot, and these will be in place for the 2024 general election. The laws place restrictions on absentee voting, impose penalties on registration efforts, adopt voter identification, and reduce the number of polling sites. For example, North Carolina lawmakers passed election laws with several troubling provisions, including eliminating the current three-day grace period for mail-in ballots, mandating mail-in ballots to be received by the Board of Elections before the polls close on Election Day, requiring local election boards to implement signature verification software for mail-in ballots, and requiring two signatures for verification on mail-in ballots. The state also implemented a restrictive voter photo identification measure after years of litigation.12

At the federal level, House Republicans have introduced the American Confidence in Elections Act, an omnibus “election integrity” bill that includes nearly fifty standalone bills, sponsored by members of the House Republican Conference, that would make it harder to vote. The measure would nationalize voter suppression and place harsh restrictions on voting rights. The Committee on House Administration Chairman Bryan Steil (R-WI) called the measure the “most conservative election integrity bill to be seriously considered in the House in over 20 years.” All of these efforts represent a concerted attempt to roll back hard-won voter protections and crush full democratic participation.13

As our current democratic crisis becomes more severe, with systemic barriers continuing to erode key democratic institutions and weaken voters’ ability to cast a ballot, grassroots organizers and advocates across states in the South have risen up in recent years as a reminder that democracy must be constantly pursued. In Georgia, for instance, thanks to years of local organizing by groups like Black Voters Matter, Fair Count, Fair Fight, New Georgia Project, and ProGeorgia, and their efforts to counter voter suppression, the Republican stronghold flipped in the 2020 presidential election. State efforts have also been more intentional about engaging with rural communities that played a major role in blocking a Republican “red wave” during the 2022 midterms. For example, in North Carolina’s state House District 73 race in rural Cabarrus County, Democrat Diamond Staton-Williams beat Republican Brian Echevarria by 629 votes out of 27,587 cast. Organizers with Down Home North Carolina, a group that works with residents of the state’s rural communities, knocked on thirty-five thousand doors and had nearly eight thousand conversations in the district.14

In recent years, important strides have also been made in offering counter-policy proposals that protect voting rights in southern states rather than undermine them. In 2021, elected officials, united with grassroots organizations including the New Virginia Majority, passed the Voting Rights Act of Virginia—the first of its kind in the South. Modeled after the federal VRA, it requires all local elections administrators to get preclearance from the state’s attorney general and prohibits racial discrimination or intimidation related to voting.

In 2023, state leaders representing a coalition of more than a dozen research and prodemocracy organizations gathered in front of the North Carolina legislature in February to release a report titled “Blueprint for a Stronger Democracy,” offering policy proposals for creating a more sustainable and inclusive election system. The report was developed by the Institute for Southern Studies, a nonprofit media, research, and education center based in Durham, North Carolina, and North Carolina Voters for Clean Elections, a nonpartisan prodemocracy coalition. The Blueprint includes policies related to voting access, election integrity, voter intimidation, campaign finance reforms, and judicial accountability, policies that have been embraced in other states by both Democrats and Republicans. “Democracy shouldn’t be a partisan issue,” the authors stated. “Together, we can find workable solutions that bring us closer to the ideal of a state truly of, by, and for the people.”15

Although organizers have been able to counter some voter suppression efforts, this has not eliminated the need for federal voting protections that can safeguard the electoral process. To overcome systemic barriers to casting a ballot, federal legislation is necessary to ensure that the voting process is freer, fairer, and more accessible. Last September, Representative Terri Sewell (D) of Alabama joined other House Democrats to reintroduce the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. The bill would reverse the Shelby ruling by creating a new formula used by the US Department of Justice in determining which states and localities need federal preclearance of election law changes. The measure focuses on states with fifteen or more voting rights violations during the past twenty-five years, those with ten or more violations if at least one was done by the state itself, and those with three or more violations if the state conducts the elections in which the violations happened. The measure would also strengthen the ability of plaintiffs to sue under Section 2 of the VRA. The measure complements another bill reintroduced last July: the Freedom to Vote Act, a far-reaching voting rights bill that would establish federal voting standards, end partisan gerrymandering, tackle felony disenfranchisement, mandate the disclosure of top donors, and create protections for nonpartisan election officials. With Republicans controlling a majority in the US House, the bills have failed to advance in Congress despite polls showing that many provisions in both bills are popular across partisan lines.16

The erosion of key voter protections has made this a critical moment for expanding and defending Americans’ access to the ballot box. In the 1960s, a previous generation of southern activists struggled to overcome systemic barriers and violence to pass federal legislation that sought to ensure all Americans were able to participate equally in the democratic process. They marched, they were beaten and imprisoned, and some even died for the right to vote. This struggle has now been passed down to a new generation of activists who are committed to ending voting discrimination and ensuring equal access to the ballot.

The current iteration of voter suppression that has swept across the South has been met by renewed organizing efforts that remain determined to fully restore the VRA and secure the promise of democracy. And now, with the 2024 election season quickly approaching, the South is once again leading the effort to determine what the next phase of American democracy will look like.

Benjamin Barber is a writer and advocate who is heavily interested in voting rights, democracy, and southern history. He currently serves as the Democracy Program Coordinator at the Institute for Southern Studies and as a contributing writer for Facing South.

NOTES

- “Remarks in the Capitol Rotunda at the Signing of the Voting Rights Act,” The American Presidency Project, accessed December 22, 2023, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-the-capitol-rotunda-the-signing-the-voting-rights-act.

- “Voting Rights Act (1965),” National Archives, Milestone Documents, last reviewed February 8, 2022, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/voting-rights-act; Farrell Evans, “How Jim Crow-Era Laws Suppressed the African American Vote for Generations,” History.com, updated August 8, 2023, https://www.history.com/news/jim-crow-laws-black-vote; Ari Berman, “John Lewis’s Long Fight for Voting Rights,” The Nation, June 5, 2013, https://www.thenation.com/article/politics/john-lewiss-long-fight-voting-rights/.

- Jeffrey Rosen, “‘Give Us the Ballot,’ by Ari Berman,” New York Times, August 25, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/30/books/review/give-us-the-ballot-by-ari-berman.html; Ari Berman, Give Us the Ballot: The Modern Struggle for Voting Rights in America (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux: 2015), 6; Allen v. State Bd. of Elections, 393 U.S. 544 (1969), Justia, accessed December 21, 2023, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/393/544/.

- Berman, “John Lewis’s Long Fight for Voting Rights”; “Jurisdictions Previously Covered by Section 5,” Civil Rights Division, US Department of Justice, updated May 17, 2023, https://www.justice.gov/crt/jurisdictions-previously-covered-section-5; “The Voting Rights Act: Protecting Voters for Nearly Five Decades,” Brennan Center for Justice, February 26, 2013, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/voting-rights-act-protecting-voters-nearly-five-decades.

- Shelby County v. Holder, Oyez, accessed December 21, 2023, www.oyez.org/cases/2012/12-96; “The Formula Behind the Voting Rights Act,” New York Times, June 23, 2013, https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/interactive/2013/06/23/us/voting-rights-act-map.html; Bob Moser, “The Voter Suppression Chronicles,” The American Prospect, June 20, 2019, https://prospect.org/power/voter-suppression-chronicles/.

- Vann R. Newkirk II, “How Shelby County v. Holder Broke America,” The Atlantic, July 10, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2018/07/how-shelby-county-broke-america/564707/; Betty Little, “How Power Grabs in the South Erased Reforms After Reconstruction,” History.com, July 19, 2023, https://www.history.com/news/voter-suppression-after-reconstruction-southern-states; “North Carolina Voter Suppression Law: North Carolina NAACP v. McCrory,” Democracy Docket, last updated May 10, 2022, https://www.democracydocket.com/cases/north-carolina-voter-suppression-law/.

- Madeleine Greenberg and Rachel Selzer, “How the U.S. Supreme Court’s Decision in Allen v. Milligan Will Impact Ongoing Redistricting Litigation,” Democracy Docket, June 8, 2023, https://www.democracydocket.com/analysis/how-the-u-s-supreme-courts-decision-in-allen-v-milligan-will-impact-ongoing-redistricting-litigation/; “Allen v. Milligan,” SCOTUS blog, accessed December 21, 2023, https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/merrill-v-milligan-2/; Mark Joseph Stern, “How the Supreme Court Likely Handed Control of the House to Republicans,” Slate, November 9, 2022, https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2022/11/supreme-court-republican-control-house-alito-mccarthy-gift.html; Mark Joseph Stern, “The Midterms Are About Rigged Maps and Republican Judges,” Slate, November 2, 2022, https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2022/11/the-midterms-are-about-courts-rigging-the-outcome.html.

- United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit, No. 22-1395, Arkansas State Conference NAACP; Arkansas Public Policy Panel, Democracy Docket, accessed December 22, 2023, https://www.democracydocket.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Opinion.pdf; Robert Barnes and Ann E. Marimow, “Supreme Court Allows Texas Voting Map Challenged by Civil Rights Advocates,” Washington Post, December 13, 2023, www.washingtonpost.com, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2023/12/12/galveston-texas-voting-map-supreme-court/.

- Nick Corasaniti, “Voting Rights and the Battle Over Elections: What to Know,” New York Times, December 29, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/article/voting-rights-tracker.html; Kevin Morris and Coryn Grange, “Large Racial Turnout Gap Persisted in 2020 Election,” Brennan Center for Justice, August 6, 2021, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/large-racial-turnout-gap-persisted-2020-election.

- Morris and Grange, “Large Racial Turnout Gap Persisted”; Eric Jensen et al., “2020 U.S. Population More Racially and Ethnically Diverse Than Measured in 2010,” United States Census Bureau website, August 12, 2021, https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/2020-united-states-population-more-racially-ethnically-diverse-than-2010.html; Will Wilder and Stuart Baum, “5 Egregious Voter Suppression Laws from 2021,” Brennan Center for Justice, January 31, 2022, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/5-egregious-voter-suppression-laws-2021.

- Stephen Fowler, “Why Do Nonwhite Georgia Voters Have To Wait In Line For Hours? Too Few Polling Places,” NPR website, October 17, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/10/17/924527679/why-do-nonwhite-georgia-voters-have-to-wait-in-line-for-hours-too-few-polling-pl.

- Christina A. Cassidy, “Voting Experts Warn of ‘Serious Threats’ for 2024 from Election Equipment Software Breaches,” PBS Newshour website, December 5, 2023, https://www-pbs-org.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/www.pbs.org/newshour/amp/politics/voting-experts-warn-of-serious-threats-for-2024-from-election-equipment-software-breaches; Benjamin Barber, “Violent Far-Right Rallies Fueled by Baseless Voter Fraud Claims,” Facing South, January 15, 2021, https://www.facingsouth.org/2021/01/violent-far-right-rallies-fueled-baseless-voter-fraud-claims; “Voting Laws Roundup: October 2023,” Brennan Center for Justice, October 19, 2023, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/voting-laws-roundup-october-2023; Benjamin Barber, “10 Years Post-Shelby, N.C. Lawmakers Advance Slate of New Voter Restrictions and Election Changes,” Facing South, June 29, 2023, https://www.facingsouth.org/2023/06/10-years-post-shelby-nc-lawmakers-advance-slate-new-voter-restrictions-and-election-changes.

- ACE Act Bill, Democracy Docket, July 2023, https://www.democracydocket.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/ACE_Act_Bill_Text.pdf; Chairman Bryan Steil, Committee on House Administration, “Chairman Steil Introduces American Confidence in Elections Act,” press release, July 10, 2023, https://cha.house.gov/2023/7/chairman-steil-introduces-american-confidence-elections-act.

- Benjamin Barber, “Rural and Low-Income Voters Build Power to Transform the South,” Facing South, December 1, 2022, https://www.facingsouth.org/2022/12/rural-low-income-voters-build-power-transform-south; “11/08/2022 Official General Election Results – Statewide,” North Carolina State Board of Elections, November 8, 2022, https://er.ncsbe.gov/?election_dt=11/08/2022&county_id=0&office=NCH&contest=1234.

- Benjamin Barber and Chris Kromm, “North Carolina Advocates Offer Detailed Blueprint to Strengthen Democracy,” Facing South, February 16, 2023, https://www.facingsouth.org/2023/02/north-carolina-blueprint-to-strengthen-democracy; Institute for Southern Studies in partnership with NC Voters for Clean Elections, “Blueprint for a Stronger Democracy,” Spring 2023, https://www.southernstudies.org/sites/default/files/23NCBlueprintMayUpdate.pdf.

- H.R.4 – John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2021, Congress.gov, accessed December 22, 2023, https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/4; “Fact Sheet: The John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act,” Brennan Center for Justice, September 19, 2023, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/john-lewis-voting-rights-advancement-act; H.R.4 – John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2021, congress.gov, accessed December 22, 2023, https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/4/text; “Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act,” Civil Rights Division, U.S. Department of Justice, updated April 5, 2023, https://www.justice.gov/crt/section-2-voting-rights-act; H.R.11 – Freedom to Vote Act, Congress.gov, accessed December 22, 2023, https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/11/cosponsors?s=1&r=78&overview=closed; Navigator, Global Strategy Group, “Voting and Democracy: A Guide for Advocates,” November 2, 2021, https://navigatorresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Navigator-Update-11.02.2021.pdf.