“It is tempting to think of universal voting rights as one of the fundamental pillars of our country, but access to the vote has been hard fought and remains under attack.”

The Voting Rights Act (VRA), which was signed into law on August 6, 1965, was a significant victory for the Civil Rights Movement, southern African Americans, and American democracy. It outlawed many of the strategies that had been used by white supremacists to disenfranchise Black citizens and included provisions to facilitate the registration of new voters. Together with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the VRA ended most of the remaining legal forms of white supremacy. Although this was tremendously important, it did not end all forms of racial discrimination, many of which were—and are—strongly embedded in the structures of our society.

Many people understand history through a top-down lens. For the Voting Rights Act, that approach gives President Lyndon Johnson, along with Martin Luther King Jr., most of the credit for this important legislation. While both men played key roles, the VRA came into being through intensive organizing and activism spearheaded by the Black community, including people who are often marginalized and not seen as central to our democracy. It is tempting to think of universal voting rights as one of the fundamental pillars of our country, but access to the vote has been hard fought and remains under attack. It isn’t enough to pass a law or secure voting rights once. We are in the midst of a tremendous battle. Will our democracy hold? Will we be able to obtain voting rights for all?

Moreover, although voting rights have always been essential, they do not alone guarantee equality. The fight to ensure civil and human rights for all must be ongoing. An understanding of the untold history of the VRA can inform and strengthen that struggle.

1. Long before the Voting Rights Act, Reconstruction launched another vibrant period of democracy and voting rights

During Reconstruction, African Americans used the vote to democratize the South. Although only men were allowed to vote in formal elections, women and children often participated actively in Black community meetings, even voting on delegates and platforms. Black women often accompanied men to the polls, sometimes bringing weapons for protection.

This community-wide engagement with the vote translated into progressive laws, including policies that laid the foundation for free universal public education, not just for Black people, but for poor white people who also were denied access to education. As with many rights secured by the African American struggle, the Black vote expanded benefits beyond the Black community.1

2. Black voting rights have been attacked and rolled back throughout our history

Massive fraud and domestic terrorism undermined the political power African Americans gained during Reconstruction. The federal government stood by as white supremacists regained control by overthrowing duly elected state and local governments. The timing and process varied across the South, but the end result was the reestablishment of white oppression through Jim Crow laws that remained in place until the modern Civil Rights Movement.

A prime example is Wilmington, North Carolina, in 1898, where white people in the Democratic Party conducted a coup d’état that annihilated the legitimately elected local government (an alliance of Black Republicans and white populists) and destroyed the Black newspaper. Reports vary widely, but at least twenty-five (and possibly more) African Americans were murdered, and many others fled in response to this violent assertion of white power.2

3. From the end of Reconstruction, which formally ended in 1877, through the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, white supremacists used numerous tactics to keep African Americans from accessing their constitutional right to vote

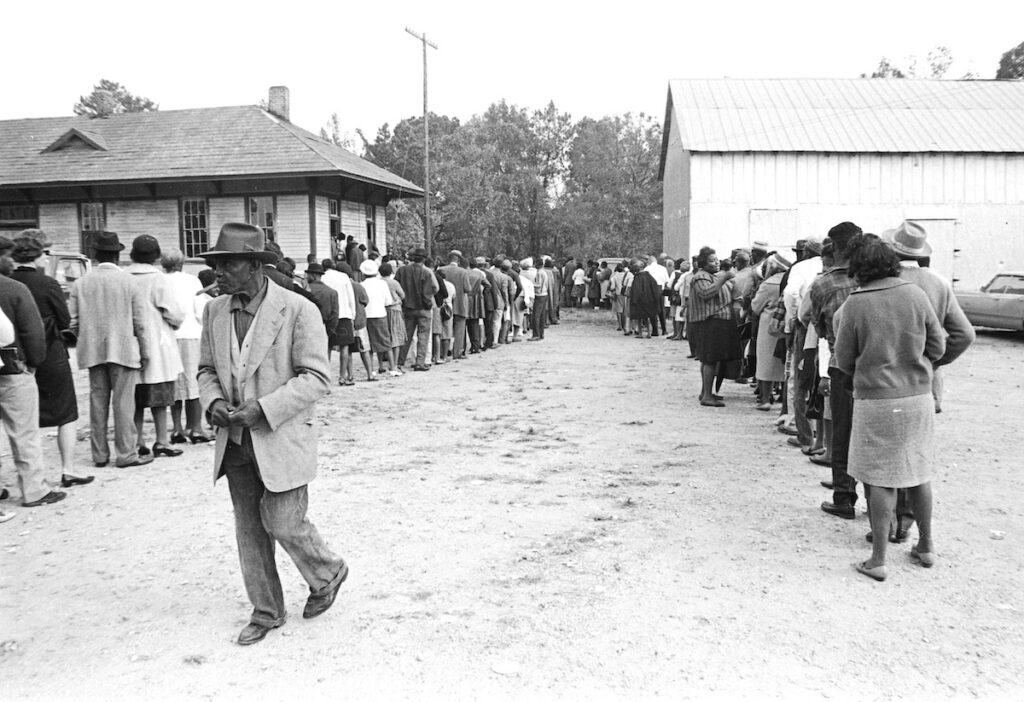

These tactics included the “grandfather clause” (which limited voting to those whose grandfathers had voted), literacy and comprehension tests, the white primary (which limited participation in the Democratic Party primary to white people), and the poll tax (which required a tax payment to vote)—all applied almost exclusively to African Americans. White people also used economic terrorism and violence to harass and punish potential (and actual) voters. The impact was wide-scale disfranchisement based on race. For example, in Lowndes County, Alabama, at the beginning of 1965, no Black person had been allowed to register to vote, even though Black people made up 81 percent of the county’s population. In contrast, approximately 130 percent of eligible white people were on the rolls (twenty-five hundred white people were registered to vote although only nineteen hundred were eligible), a clear example of fraud. It took sustained organizing and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to change those numbers in any substantial way.3

Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer describes what happened when she took the registration test in Mississippi in August 1962:

Well, there was 18 of us who went down to the courthouse that day and all of us were arrested. Police said that the bus was painted the wrong color—said it was too yellow … I went back to the plantation where [my husband] Pap and I had lived for eighteen years. My oldest girl met me and told me that Mr. Marlowe, the plantation owner, was mad and raising sand. He had heard that I had tried to register. That night he called on us and said, “We’re not going to have this in Mississippi and you will have to withdraw … If you don’t withdraw you will have to leave.” … So I left that same night. Pap had to stay on till work on the plantation was through. Ten days later they fired into Mrs. Tucker’s house where I was staying. They also shot two girls at Mr. [Sisson’s].4

Even as Mrs. Hamer and her husband struggled to find work and housing to care for their family, she continued her activism. A year after her first attempt to register, Mrs. Hamer and eight other people returning from Citizenship Education training were arrested and viciously beaten. She recalled, “after I got out of jail, half dead, I found out that [Mississippi NAACP director] Medgar Evers had been shot down in his own yard.” Testifying at the 1964 Democratic Convention, Mrs. Hamer said, “All of this is on account of we want to register, to become first-class citizens.” She concluded with these words:

If the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question America. Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?5

4. The modern voting rights struggle had deep roots in the rural South

At times African Americans prioritized improving educational opportunities, securing land ownership, and developing the institutions—such as churches—that later provided a critical base for the Civil Rights Movement, but they never conceded their right to vote. Even when it was extremely dangerous, there were always men and women trying to register and vote. In 1944, the NAACP won a landmark case, Smith v. Allwright, overturning the white primary—in which only white voters could participate in political primaries. This victory inspired an upsurge in Black voter registration that was reinforced by Black World War II veterans returning home from overseas. One of these veterans was Medgar Evers, who became Mississippi’s first NAACP field secretary and was assassinated in June 1963 for his civil rights work. He describes his first attempt to vote after successfully registering:

[S]ix of us gathered at my house and we walked to the polls. I’ll never forget it. Not a Negro was on the streets, and when we got to the courthouse, the clerk said he wanted to talk with us. When we got into his office, some 15 or 20 armed white men surged in behind us, men I had grown up with, had played with. We split up and went home. Around town, Negroes said we had been whipped, beaten up, and run out of town. Well, in a way we were whipped, I guess, but I made up my mind then that it would not be like that again, at least not for me.6

In 1955, the Regional Council of Negro Leadership (RCNL), which Evers and World War II veteran Amzie Moore helped lead, hosted a meeting of more than ten thousand Black citizens in the all-Black town of Mound Bayou, Mississippi. According to Ebonymagazine, Moore was almost trampled by Black attendees grabbing for the voter registration forms he was giving out.

Following the Supreme Court’s school integration decision in Brown v. Board of Education, white supremacists founded the white Citizens’ Council to oppose integration and Black voting rights. This was part of a huge and violent backlash by white supremacists. The RCNL‘s large gatherings became impossible, and many Black leaders were forced out of the state.7

5. The federal government has played a contradictory role in the fight for voting rights

The Supreme Court gradually outlawed discriminatory practices, like the grandfather clause, the white primary, and the poll tax, but in general the federal government played a relatively passive role. This was exacerbated by the power of southern Democrats (known as Dixiecrats) in Congress who used their power to advance states’ rights and white supremacy. Partly because of the suppression of the Black vote, many Dixiecrats had considerable seniority, which allowed them to control key committees and make it difficult to pass civil rights legislation. Even when the Kennedy Justice Department used what civil rights activist Bob Moses calls “the crawl space” created by the 1957 Civil Rights Act to file lawsuits charging numerous southern officials with suppressing the Black vote, their work was undermined by other branches of the federal government that supported the Dixiecrats.8

Some white supremacist judges, including a few nominated by President John Kennedy, blocked the department’s work at every turn, and the FBI only reluctantly carried out the necessary investigations. Under the leadership of J. Edgar Hoover, the FBIwas more interested in undermining the efforts of Martin Luther King Jr. than helping the Justice Department prove its racial discrimination cases. Moreover, after initially promising to protect anyone working on voter registration, the Kennedy administration backtracked, and FBI agents flatly refused to protect civil rights workers, even when they witnessed attacks on federal property. More lives might have been lost if local Black citizens had not used their guns in self-defense to protect themselves and the young organizers they were working with.9

6. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s organizing around voter registration fundamentally changed our country, both because of what they did and how they did it

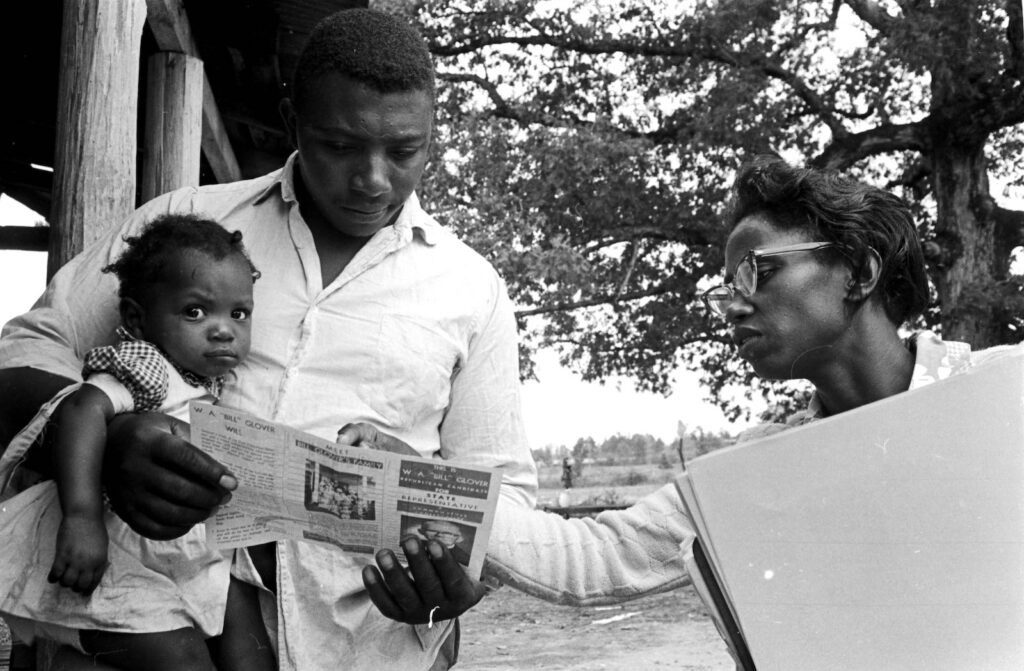

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), an organization of young people that emerged from the 1960 sit-in movement, developed an approach to grassroots community organizing that has influenced every subsequent progressive movement. Their voter registration work in the Deep South was built around canvassing—going door to door, talking to people—and relied on patience, education, and building relationships. This work took place out of the spotlight, with few quick victories. It could be slow and tedious, but it was essential to protecting and expanding the vote.

Influenced by their mentor, Ms. Ella Baker, and community leaders, the young people in SNCC made decisions by consensus, helped develop leadership skills in others, and challenged hierarchies that privileged wealth and education. In the summer of 1961, a group of about sixteen young people put school and jobs on hold to become SNCC‘s first field staff and commit to full-time movement work. Their approach to voter registration, which quickly found a base in the Mississippi Delta, was strongly influenced by NAACP leader Amzie Moore, working closely with SNCC‘s Bob Moses. Over the next four years—working with other organizations and allies—SNCC was successful at organizing rural African American communities, making it difficult for the country to ignore the violence and discrimination at the heart of Jim Crow and white supremacy. Though SNCC did not act alone, their work was at the heart of the organizing that led directly to the Voting Rights Act, which expanded the electorate and ended the undemocratic stranglehold of the southern Dixiecrats. Their work opened up the national Democratic Party, forcing a rules change that made it more explicitly representative (by race, ethnicity, and gender).10

Perhaps most importantly, SNCC recognized and nurtured leadership in people like Mrs. Hamer, whom the rest of the country had dismissed. She went from a circumscribed life as a sharecropper with a sixth-grade education to being a nationally recognized leader and one of the first Black women seated on the floor of the Senate. SNCC‘s alliance with these everyday people breathed new life into our democracy, challenging longstanding ideas of who was qualified to hold power and make decisions.11

7. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee upended traditional ideas about who was qualified to vote

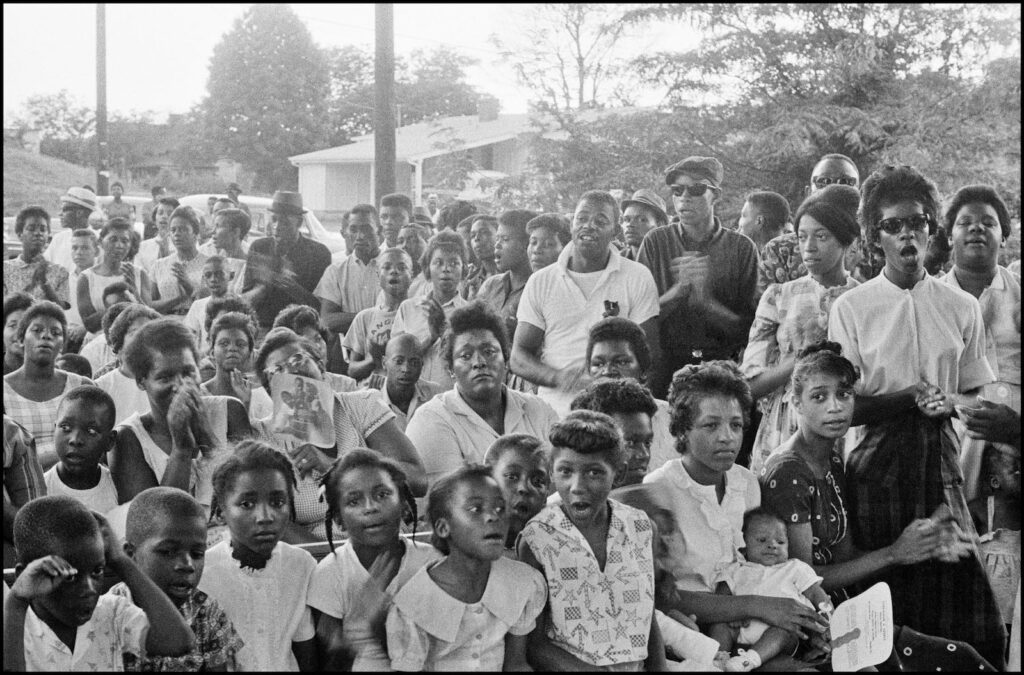

White supremacists responded to the voting rights campaign by manipulating the registration process, as well as by firing, evicting, and terrorizing Black communities with beatings, murders, and church burnings. White officials then used the low numbers of African Americans registered to vote to insist that Black people had no interest in politics. In response, SNCC organized Freedom Days, first in Selma, Alabama, in 1963, then in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, in 1964. With little chance of being allowed by white officials to register or to vote, Black people stayed in line, in punishing heat and pouring rain, refusing to be intimidated by white threats and harassment and demonstrating their strong desire to vote.12

Working with the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), a coalition of civil rights groups, SNCC also organized a Freedom Vote, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, and a Congressional Challenge to the all-white Mississippi delegation to the House of Representatives. Each was designed to demonstrate that Black people did want to vote and participate in politics. In addition, each tactic provided an important experiential education for people who had been excluded from the political process for almost a century. Throughout this process, SNCC field secretaries were learning from the people they were working with. SNCC field secretary Prathia Hall reflected,

The local people had the wisdom of the elders—or perhaps the wisdom of the ages—to share with us. They had lived under that system of domination and brutality for generations. Everyone knew someone whose loved one had been beaten or killed by its violence. They also knew about life and how to live life without surrendering humanity or dignity to those who sought to crush them. It was an exchange of mutual learning.13

By 1963, in addition to helping Black people improve their literacy, SNCC began to challenge the literacy tests, required almost exclusively of Black people. Bob Moses pointed out that white Mississippians used the political process to deny Black people access to a quality education and then used their poor education to deny them access to the political process. Moreover, they had encountered many people who had been denied education but still had more than enough wisdom to vote on their representatives.14

8. Though Martin Luther King Jr. and President Lyndon Johnson are typically credited with passage of the Voting Rights Act, an organized grassroots movement made it happen

President Lyndon Johnson supported the Voting Rights Act, but the critical push for the legislation came from the Movement itself. SNCC organizers played a key role in demonstrating—and documenting—the unrelenting, often violent, and officially sanctioned discrimination that prospective Black voters faced. This gave Justice Department officials, including attorney John Doar, clear examples of discrimination in the voting rights lawsuits they filed against hostile white registrars in the Deep South. Doar asserted that the visible voting rights successes in Selma in 1965 were built on SNCC‘s earlier but more obscure voter registration work in the Mississippi Delta. That work prompted the department’s initial development of a comprehensive new approach to voting rights protection, which became the template for the department’s interventions in Selma.

All this earlier grassroots organizing, in conjunction with the demonstrations led by King in Selma, Alabama, generated the public support that led to crucial voting rights legislation.15

9. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee sought not only Black access to the vote, but also to transform voting into “freedom politics” and small-d democracy for all

After walking through Lowndes County during the well-known 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery, SNCC organizers returned to the county known as “Bloody Lowndes,” intent on using the Voting Rights Act to improve the daily lives of African Americans in the community. The organizing effort in Lowndes County provides a wonderful case study of SNCC‘s approach to using the vote to gain power. As they considered their options—including a racist state Democratic Party (which had “white supremacy for the right” as its slogan) and a nationally mixed, but locally nonexistent Republican Party—SNCC‘s Courtland Cox asked, “What would it profit a man to have the vote and not be able to control it?” He explained,

The Negroes of Lowndes County want a political grouping that is controlled by them. They want a political grouping that is responsive to the needs of the poor, not necessarily the black people, but those who are illiterate, those who have poor educations, those of low income, that is to say, those who are [considered] unqualified in this society. To do this they had to form a group on the county level that represented their own interests.16

Based on this idea, SNCC worked with local residents to form an independent political party, the Lowndes County Freedom Party (LCFP). According to Gloria House, a SNCC field secretary, “We were helping to equip the people with the information and skills essential to running the county themselves not just as new voters but also as political leaders. We found that a review of African American and African history, giving a strong sense of historical identity, was of immeasurable significance in this process.”17

In fact, according to historian Hasan Kwame Jeffries, SNCC “developed a unique political education program for Lowndes County residents that used workshops, mass meetings, and primers to increase general knowledge of local government and democratize political behavior.” This wasn’t just voting or even politics as usual. Jeffries explains that SNCC linked their “egalitarian organizing methods” with the people’s civil and human rights goals to create what he calls “freedom politics,” an approach that rejected traditional American politics and instead emphasized organizing around the issues raised by the community. The LCFP developed its platform before nominating candidates, and the candidates who stepped forward reflected the community’s goals. For example, Alice Moore, who ran for tax assessor, announced that, if elected, she would “tax the rich to feed the poor.”18

SNCC‘s work clearly followed Ms. Ella Baker’s belief that “in order for us as poor and oppressed people to become part of a society that is meaningful, the system under which we now exist has to be radically changed. … It means facing a system that does not lend itself to your needs and devising means by which you change that system.”19

SNCC‘s work in Lowndes also provided the base for their use of the phrase “Black Power,” popularized by Stokely Carmichael in June 1966. According to SNCC‘s Courtland Cox, Black Power meant: “1) the power to define oneself; 2) the power to control one’s own condition and vote to control one’s own community; and 3) the power to use politics to enhance one’s own economic condition.”20

10. The Black Panther symbol was first used in Lowndes County, Alabama

When the Lowndes County Freedom Party was founded, Alabama law required that it have a symbol to help illiterate voters. They chose the Black Panther, which was indigenous to Lowndes, as their ballot symbol.

John Hulett explains, “This black panther is a vicious animal as you know. He never bothers anything, but when you start pushing him, he moves backwards, backwards, backwards into his corner, and then he comes out to destroy everything that’s before him.” When young Black activists in Oakland, California, established an organization to combat police brutality, they adopted the snarling black panther symbol and the LCFP‘s informal name, the “Black Panther Party.”21

Although white southerners had a long history of using violence to maintain their power, the federal government and media expressed considerable alarm when African Americans chose the Black Panther as a symbol, exposing a persistent double standard related to race and violence. Many white Americans voiced fear of armed African Americans, as they had done historically since the slave rebellions, and called on Black citizens to be “nonviolent,” while ignoring or downplaying the persistent violence perpetrated by white people, including those in law enforcement.

11. Federal protection for voting rights is still necessary

Despite—or perhaps because of—its success, in July 2013, a deeply divided United States Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act in Shelby County v. Holder, a case coming out of Alabama. Arguing in part that it was arbitrary and no longer necessary to focus on the former Confederacy, the court’s majority eliminated the preclearance requirement—which dictated that the Justice Department or federal courts review proposed legislation to ensure that it would not have a negative impact on minority voting—for nine southern states and other jurisdictions. This meant that the Justice Department would no longer be allowed to block new voting and electoral laws that introduced racial bias. In the twenty-five years before Shelby, the Justice Department blocked eighty-six laws it found discriminatory, and many more potentially discriminatory laws were withdrawn or abandoned in the face of this oversight. It is as if Chief Justice John Roberts argued that the Voting Rights Act’s very effectiveness made it unnecessary. Within hours of the decision, Texas introduced legislation mandating voter IDs, a law that had previously been blocked for its discriminatory impact. While voter IDs might seem reasonable, consider that Texas refused to accept student IDs but recognized those issued by the National Rifle Association.

The response of Texas and other jurisdictions to Shelby makes it quite clear that we still need robust, proactive tools to protect voting rights for all citizens, but particularly African Americans, students, immigrants, and other marginalized groups. Rather than being curtailed, the Voting Rights Act should be extended. No doubt future historians will look back at today’s voter ID laws, ex-felon disfranchisement, and other forms of voter suppression (including Jim Crow voting booths) as a twenty-first-century version of the literacy tests, poll tax, and grandfather clause of the previous century.22

12. Following the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, Republican Richard Nixon developed a Southern Strategy to woo southern white Democrats, known as Dixiecrats, into the Republican Party

As the Republican Party absorbed segregationists and became whiter, the association between African Americans and the Democratic Party also intensified. In recent years, this has informed the Republican Party’s electoral strategy. As scholar Carol Anderson has noted, instead of trying to appeal to voters “on the strength of the party’s ideas,” the Republican Party has been trying to seize power through “massive disfranchisement.” They have been aided by any number of Supreme Court decisions, including the 2019 Rucho v. Common Cause case, in which the Court insisted it is powerless to prevent partisan voter suppression. Since racial and partisan voter suppression often go hand in hand, this makes challenging race-based voter suppression even more difficult. For example, if a new law unfairly targets Black voters, Republican officials can argue they are aiming at Democrats, not African Americans.23

13. On July 21, 2021, the Supreme Court continued its attack on voting rights in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, narrowing the effectiveness of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act

Section 2 prohibits the imposition of any “qualification or prerequisite to voting or standard, practice, or procedure” which denies or limits voting rights based on “race or color.” With the Shelby v. Holder decision eliminating Section 5’s preclearance requirement, Section 2 has become an essential tool in challenging discriminatory laws through legal action. In the majority opinion, Justice Samuel Alito offered up five guideposts for assessing whether a law is discriminatory enough to be overturned. In summing these up, the New York Times concluded that the court would ban discriminatory laws “only when they impose substantial and disproportionate burdens on minority voters, effectively blocking their ability to cast a ballot.” As states across the country try to outdo themselves with new and old ways of suppressing Black votes, the Supreme Court has all but killed the best tool our country has ever had for ensuring Black access to the ballot box.24

14. In the context of a severely weakened Voting Rights Act, voter suppression is widespread, deeply partisan, and effective enough that it can impact election outcomes. As the electorate grows more diverse and less likely to ally with the Republican Party, the attacks on voting rights are persistent and pervasive

The Republican Party is using the idea of fraud to justify a wide range of voter suppression tactics, including felony disfranchisement (which goes back to the Jim Crow era), voter IDs (which, among other things, can be seen as a new form of poll tax), voter purges (where large numbers of voters are eliminated from the voting rolls and have to re-register), gerrymandering, the closure of voting places, and more. The fraud that these laws are supposedly trying to prevent is virtually nonexistent. When pressed under oath, those crying loudest find it impossible to back their claims. A Heritage Foundation list that includes what it considers voter fraud and other election violations since 1982 adds up to less than one per state per year, and even that is contested.25

In Georgia, in the wake of the 2020 election where “an unprecedented number of voters (particularly Black and brown voters)” went to the polls, the legislature passed SB202, which “reduced the number of ballot boxes in communities of color, limited voting hours, added additional voter ID requirements, and made it illegal to provide those waiting in line with food or water, among other measures.” The latter ban brings to mind the 1963 arrests of two SNCC workers for trying to bring food and water to the line of more than three hundred African Americans trying to register to vote in Selma, Alabama.26

In Florida, where a Jim Crow constitution banned convicted felons from voting as “part of a slate of actions designed to remove Black voters from the rolls,” the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition led the way in a stunning voting rights victory with the 2018 passage of Amendment 4, which was intended to restore the voting rights of felons (excluding those convicted of murder and sex offenses). Before Amendment 4, an estimated 1.4 million people, including about 21 percent of otherwise eligible Black voters, could vote only if the governor approved their petition, a slow and difficult process.27

While many celebrated the tremendous victory for voting rights, the Florida legislature struck back. Relying on the fact that most of those convicted are assessed fines, fees, and restitution that they are unlikely to be able to pay, the legislature passed a law requiring that convicted felons pay all “court debts” before regaining their right to vote. Since there is no central database (one reporter described it as a “byzantine bureaucracy”) and the state leaves it up to individuals to determine their own eligibility, those who want to vote risk further arrest if they register and vote while owing money. In Georgia, Florida, and across much of the country, voter suppression is alive, intentional, effective, cruel, and unrelenting.28

15. While voter suppression efforts are rampant, African American activists and those who believe in small d-democracy, including some in Congress, are fighting back on a range of fronts

In 2021, the House of Representatives passed two key bills that, if passed by the Senate and signed into law by the president, would together ensure broad-based and fair access to the vote. The John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act (named for John Lewis, a former SNCC chair who pushed the nation to eliminate voting barriers) would restore central elements of the Voting Rights Act. In addition to undoing the Supreme Court’s damage, it would extend some of its protections to the entire nation, making it difficult to use unsupported claims of fraud to justify voter suppression. Meanwhile, the For the People Act would more broadly extend access to voter registration (including automatic and same-day voter registration), ensure broad-based voting access (including early voting and vote by mail), restore voting to returning citizens (many of those currently blocked due to criminal convictions), end partisan gerrymandering, reform campaign finance, and more. If enacted, it would greatly limit the capacity of state legislatures to implement the voter suppression proposals that have flourished since the Shelby case and intensified even more since the 2020 election. Senate Republicans used the filibuster (a tool segregationists regularly used to stop civil rights legislation) to block passage of these laws in January 2022. However, the movement has taught us two lessons: first, the federal government has a central role to play in protecting the voting rights of Americans, and second, it requires the determined and collective action of everyday people to ensure that our representatives pass laws to protect us.29

Conclusion: The Civil Rights Movement made important gains, but the struggle continues

The Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act removed most forms of legal discrimination against African Americans, but they did not bring an immediate end to the legacies of slavery and Jim Crow. Ongoing protests over police brutality and the disregard for Black lives, the persistence of extreme economic and racial segregation, and the tenacity of separate and unequal schools clearly demonstrate that although the Voting Rights Act was necessary, it is not sufficient for addressing white supremacy and oppression of people of color. Unfortunately, the words of Ms. Ella Baker, one of the most important figures in the Black freedom struggle, still echo today. In 1964 she asserted, “until the killing of black men, black mothers’ sons, becomes as important to the rest of the country as the killing of a white mother’s son, we who believe in freedom cannot rest.”30

Today, young people across the country are carrying on the struggle for racial justice, some working with the intergenerational Movement for Black Lives. Many of today’s activists are drawing on the work of SNCC, while developing new strategies and ways of analyzing the issues we face. Today’s voters face an uphill climb, as the Republican-dominated Supreme Court and state legislatures continue to aggressively undermine the right to vote. Without the Voting Rights Act’s preclearance (Shelby) and with the newly imposed, impossibly high standards for challenging voter suppression (Brnovich), our country is being flooded with discriminatory voting laws and the Supreme Court has made it even harder to challenge them.31

However, as the 2020 Georgia elections clearly demonstrated, there is considerable power and potential in the emerging coalition of voters composed of people of color, youth, independents, and progressives. Nsé Ufot, who helped engineer Georgia’s voter turnout in the 2020 election as CEO of the New Georgia Project, argued, “It’s 3 a.m., not midnight.” That is, as bleak as it may feel right now, in the face of this unrelenting voter suppression, the very strength of this backlash speaks to the power and effectiveness of contemporary organizing. In a conversation with fellow voting rights activists, including SNCC veteran Courtland Cox, who organized in Lowndes County, Alabama, in the 1960s, Ufot argues that the national Democratic Party needs its own Southern Strategy. That strategy would center Black voters, not just for turnout purposes, but in their policies. Ufot, like SNCCand others before her, believes in the power of so-called ordinary people. In her view, elections should be a starting place, with voters working as active partners alongside their elected officials. Just as the movement was made of everyday people, in Ufot’s vision, everyday people need to be about the business of governing our country. The country might then have a chance of living up to its founding ideals of equality and opportunity for all its citizens.32

Emilye Crosby is professor of history at SUNY Geneseo. She is the author of A Little Taste of Freedom: The Black Freedom Struggle in Claiborne County, Mississippi, and editor of Civil Rights History from the Ground Up. She is a founding member of the Movement History Initiative and is currently working on several projects related to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Judy Richardson was on the staff of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) from 1963 to 1966 and was a researcher, series associate producer, and education director for the fourteen-hour PBS series Eyes on the Prize. Her other films include Malcolm X: Make It Plain and Scarred Justice: The Orangeburg Massacre 1968. She is currently on the SNCC Legacy Project Board and the editorial board for the One Person, One Vote pilot collaboration between the SNCC Legacy Project and Duke University. She coedited Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC.

NOTES

An earlier version of this essay was published by Teaching for Change.

- Elsa Barkley Brown, “Negotiating and Transforming the Public Sphere: African American Political Life in the Transition from Slavery to Freedom,” Public Culture 7 (1994): 107–146.

- Adrienne LaFrance and Vann R. Newkirk II, “The Lost History of an American Coup D’État,” The Atlantic, August 12, 2017; David Cecelski and Timothy Tyson, Democracy Betrayed: The Wilmington Race Riot of 1898 and Its Legacy (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998).

- Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in the Alabama Black Belt (New York University Press, 2009); SNCC Research, “Lowndes County, Alabama,” September 5, 1965, accessed August 12, 2023, https://www.crmvet.org/docs/6509_sncc_research_lowndes.pdf.

- Fannie Lou Hamer, “To Praise Our Bridges,” in The Eyes on the Prize Civil Rights Reader, ed. Clay-borne Carson et al. (New York: Penguin, 1991), 178–179.

- Jerry DeMuth, “Fannie Lou Hamer: Tired of Being Sick and Tired,” The Nation, June 1, 1964; Fannie Lou Hamer Testimony at the Democratic National Convention, 1964, accessed August 9, 2023, https://www.americanyawp.com/reader/27-the-sixties/fannie-lou-hamer-testimony-at-the-democratic-national-convention-1964/.

- Jeffries, Bloody Lowndes, 1–38; Charles Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition in the Mississippi Delta (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 1–66; John Dittmer, Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 1–70, esp. 2, 4; Michael Edward Vinson, Francis Mitchell interview with Medgar Evers, quoted in Medgar Evers: Mississippi Martyr(Fayetteville: University of Arkansas, 2013), 40.

- Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom, 29–66, esp. 58–59.

- Civil Rights Movement Archive, “Reflections from Bob Moses on the Mississippi Theater of the Civil Rights Movement on the Occasion of the Passing of John Doar,” accessed August 11, 2023, https://www.crmvet.org/comm/1411_doar-moses.pdf.

- Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom; Dittmer, Local People; Kenneth O’Reilly, Racial Matters: The FBI’s Secret File on Black America, 1960–1972(New York: Free Press, 1991).

- Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom; Barbara Ransby, Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003); Dittmer, Local People, 272–302, 429–430; James Forman, The Making of Black Revolutionaries (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1972, 1997).

- Maegan Parker Brooks, A Voice that Could Stir an Army: Fannie Lou Hamer and the Rhetoric of the Black Freedom Movement (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014).

- Forman, The Making of Black Revolutionaries, 345–354; Dittmer, Local People, 215–241.

- Prathia Hall, “Freedom-Faith,” in Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC, ed. Faith Holsaert et al. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012), 176.

- Forman, Making of Black Revolutionaries, 304–307.

- John Doar, “The Work of the Civil Rights Division in Enforcing Voting Rights Under the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960,” Florida State University Law Review 25, no. 1 (1997), 1–17; John Doar at “We the People” conference, Tougaloo College, May 9, 2012, notes in author’s possession.

- Courtland Cox, “What Would It Profit a Man to Have the Vote and Not Be Able to Control It?,” 1965 or 1966, accessed August 8, 2023, https://www.crmvet.org/docs/courtcox.htm.

- Gloria House, “We’ll Never Turn Back,” in Hands on the Freedom Plow, 528.

- Jeffries, Bloody Lowndes, 145, 4, 8.

- Ella Baker, quoted in Ransby, Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement, 7.

- Courtland Cox in founding meeting for Movement History Initiative, Duke University, November 2013, notes in author’s possession. For more information about the Movement History Initiative, see https://library.duke.edu/rubenstein/franklin/movement-history-initiative, accessed August 10, 2023.

- John Hulett, “How the Black Panther Party Was Organized,” May 22, 1966, in The Eyes on the Prize Civil Rights Reader, 273–278; Stokely Carmichael and Michael Thelwell, Ready for Revolution: The Life and Times of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture) (New York: Scribner, 2005), 475–477; Hasan Kwame Jeffries, “SNCC, Black Power, and Independent Political Party Organizing in Alabama, 1964–1966,” Journal of African American History 91, no. 2 (Spring 2006): 171–193.

- Brennan Center, “Testimony of Michael Waldman,” Hearing on Voting in America, June 24, 2021, House Committee on Administration, Subcommittee on Elections, US House of Representatives, accessed August 11, 2023, https://www.brennancenter.org/media/7831/download; Ed Pilkington, “Texas Rushes Ahead with Voter ID Law after Supreme Court Decision,” The Guardian, June 25, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jun/25/texas-voter-id-supreme-court-decision.

- Carol Anderson, One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression Is Destroying Our Democracy (New York: Bloomsbury, 2018), 70; Adam Liptak, “Supreme Court Bars Challenges to Partisan Gerrymandering,” New York Times, June 17, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/27/us/politics/supreme-court-gerrymandering.html; Ian Millhiser, “How the Supreme Court Revived Jim Crow Voter Suppression Tactics: Carol Anderson Explains What Happens When Our Voting Rights Laws Start to Crumble,” Vox, September 21, 2020, https://www.vox.com/21445460/supreme-court-voter-suppression-jim-crow-carol-anderson-shelby-county.

- Brennan Center, “Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee,” Brennan Center for Justice, January 19, 2021, updated July 1, 2021, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/court-cases/brnovich-v-democratic-national-committee; Sean Morales-Doyle, “The Supreme Court Case Challenging Voting Restrictions in Arizona, Explained,” Brennan Center for Justice, February 25, 2021, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/supreme-court-case-challenging-voting-restrictions-arizona-explained; Adam Liptak, “Supreme Court Upholds Arizona Voting Restrictions,” New York Times, July 1, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/01/us/politics/supreme-court-arizona-voting-restrictions.html.

- Anderson, One Person, No Vote, 42, 47–56; Millhiser, “How the Supreme Court Revived Jim Crow Voter Suppression Tactics”; Carol Anderson, “Republican Approach to Voter Fraud: A Lie,” New York Times, September 8, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/08/opinion/sunday/voter-fraud-lie-missouri.html; Rudy Mehrbani, “Heritage Fraud Database: An Assessment,” Brennan Center for Justice, September 8, 2017, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/heritage-fraud-database-assessment.

- League of Women Voters, accessed October 3, 2023, https://www.lwv.org/voting-rights/fighting-voter-suppression; Howard Zinn in James Forman, The Making of Black Revolutionaries (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1972, 1997), 351–352.

- Lawrence Mower and Langston Taylor, “In Florida, the Gutting of a Landmark Law Leaves Few Felons Likely to Vote,” ProPublica, October 7, 2020, https://www.propublica.org/article/in-florida-the-gutting-of-a-landmark-law-leaves-few-felons-likely-to-vote.

- Sam Levine, “How Republicans Gutted the Biggest Voting Rights Victory in Recent History,” The Guardian, August 6, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/aug/06/republicans-florida-amendment-4-voting-rights; Mower and Taylor, “In Florida, the Gutting of a Landmark Law Leaves Few Felons Likely to Vote”; Brennan Center, “Testimony of Michael Waldman,” Hearing on Voting in America, June 24, 2021, House Committee on Administration, Subcommittee on Elections, US House of Representatives, https://www.brennancenter.org/media/7831/download.

- Brennan Center, “The John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act,” Brennan Center, December 22, 2021, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/john-lewis-voting-rights-advancement-act; “Summary: For the People Act,” League of Women Voters, accessed October 3, 2023, https://my.lwv.org/new-york/utica-rome-metropolitan-area/article/summary-people-act; Wendy R. Weiser, Danien I. Weiner, and Dominique Erney, “Congress Must Pass the ‘For the People Act,'” Brennan Center, January 29, 2021, updated March 18, 2021, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/policy-solutions/congress-must-pass-people-act; Carl Hulse, “After a Day of Debate, the Voting Rights Bill Is Blocked in the Senate,” New York Times, January 19, 2022, updated January 27, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/19/us/politics/senate-voting-rights-filibuster.html.

- Bernice Johnson Reagon, “Composer’s Notes for Ella’s Song,” in Continuum: The First Songbook of Sweet Honey in the Rock, ed. Ysaye Maria Barnwell with Sweet Honey in the Rock (Southwest Harbor, ME: Contemporary A Cappella Publishing, 1999), 135–137.

- Movement for Black Lives, accessed August 16, 2023, https://m4bl.org/.

- Nsé Ufot with Courtland Cox and Charles Taylor, Conversation as part of the Movement History Initiative, April 7, 2023. Read an excerpt of this conversation on p. 98.