In 2017, I was knee-deep in queer southern literature. Unbeknownst to my colleagues and students at the University of Mississippi, I was building a stock list for Violet Valley Bookstore, Mississippi’s only queer feminist bookshop, which I planned to open in November of that year. I was teaching a syllabus I’d developed for a graduate seminar on the Queer South for only, I think, the second time. Of course, I included Men Like That, which I stumbled upon during my first semester at the University of Mississippi, and which transformed my vision of my adopted state, permanently. While working on revisions for my book, The Lesbian South, which would be published the following fall, I was starting my second year as director of the gender studies program. And in the first year of the first Trump presidency, I was thinking about resistance and community and the queer southern culture I had fallen in love with nearly fifteen years before, and how to best support that culture in the current cultural moment.

The Queer South seminar drew a lot of graduate student interest, unsurprising at a university that had both southern studies students and English graduate students eager to study the region. I had already added students over the number permitted and gotten in trouble with my chair because of it. And then I received some insistent emails from a new southern studies ma who asked to be let into the class. At one point, he wrote to tell me that he had already read the book for the first week, John Howard’s Men Like That. I didn’t know it at the time, but Men Like That was the book that had inspired him to go to graduate school. Luckily, right before the semester started, one enrollee dropped out, and I was able to email this persistent student and tell him I could add him to the course. So on that first day of class, I met Hooper Schultz, who would become a graduate assistant, fellow scholar, and friend. It is a privilege to revisit the queer South with him as he completes his dissertation and builds his own scholarly career. —Jaime Harker

As Jaime recounts, I was that persistent graduate student back in 2017. A year earlier, I’d been working for a small magazine company in a venerable southern city. I had no career growth prospects and was chafing at the strictures of what we published. I kept catching whispers of the lives of gay, lesbian, and gender-nonconforming people who had lived in the history of this particular city, and I was hoping to follow where those whispers led. To my chagrin, the editor wasn’t interested in these histories. Simply put, they didn’t fit our market. So I struck out on my own. I had never expected to go back to school. I graduated with a BA in English in 2010 and began working in journalism and publishing without looking back. As I began ordering books to feed my growing hunger for the history of the queer South, I started to ponder how I too could get the space (and funding) to research and write about a topic near and dear to my own heart as a queer southerner. Howard’s Men Like That (along with Bob Korstad and Jim Leloudis’s To Right These Wrongs) led me to the program in southern studies at the University of Mississippi.

Through the interdisciplinary program, with the indispensable guidance of scholars like Jaime Harker and Jessie Wilkerson, I began to think through how I wanted to engage in the study of the queer South. Although my own path moved toward history as a concrete discipline, my earlier training in literature and cultural studies continues to influence my approach. Studying the queer South necessarily muddies the waters between the academy’s silos, and Jaime’s Queer South class—part survey of queer southern literature, part cultural studies, part history of queerness in the South—was a perfect introduction to this method.

It was my incredible fortune to be in Jaime’s course in that heady first semester in Oxford, Mississippi, and I will forever be grateful to her for taking me under her wing and to the queer folks I came into community with. I will never forget driving down Route 7 to Water Valley, Mississippi, and helping to shelve queer literature for the opening of Violet Valley. I learned, in those years in Mississippi, that seemingly small efforts, spaces, and groups can have an outsized effect on their communities. In fact, I’m convinced that these are the most powerful units of action as we face a world in which fascism, homophobia, and antitrans rhetoric and politics are on the rise.

This moment, in the first year of the second Trump presidency, is an ideal time to look backward and forward, to the scholarship about the queer South that has increased even in the last eight years, and to the principled moxie the queer community has shown in the midst of our current homophobic and transphobic backlash. We are grateful to the Southern Cultures community for their interest in this special issue, continuing a long focus on the queer South at the journal. We are also grateful for the many great submissions we received for this special issue—enough for four issues, to be honest. Selecting just a few essays from this amazing collection of scholarship was the most difficult task we faced, and we hope other journals and presses will add their own monograph series and special issues on the queer South. —Hooper Schultz

Scholarly and Imaginative Work on the Queer South

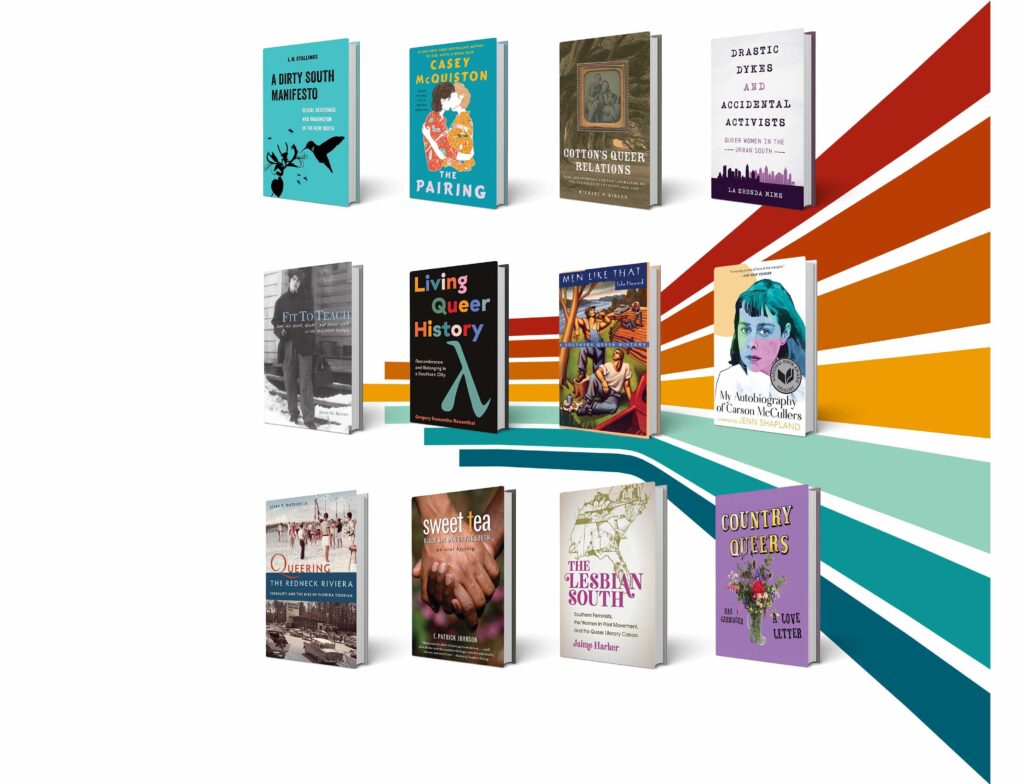

Most studies of the queer South begin with John Howard’s book Men Like That: A Southern Queer History. The book is widely credited as creating a new specialty: queer rurality in queer studies, in contrast to the metronormativity that (still) largely fuels queer studies. Its influence on southern studies is also immense, as it creates new possibilities and invites scholars to follow new threads. Howard invented his own interdisciplinary method for studying the queer South, through oral history, geography, and book history, but also through key tropes: mobility, scandal, narratives.

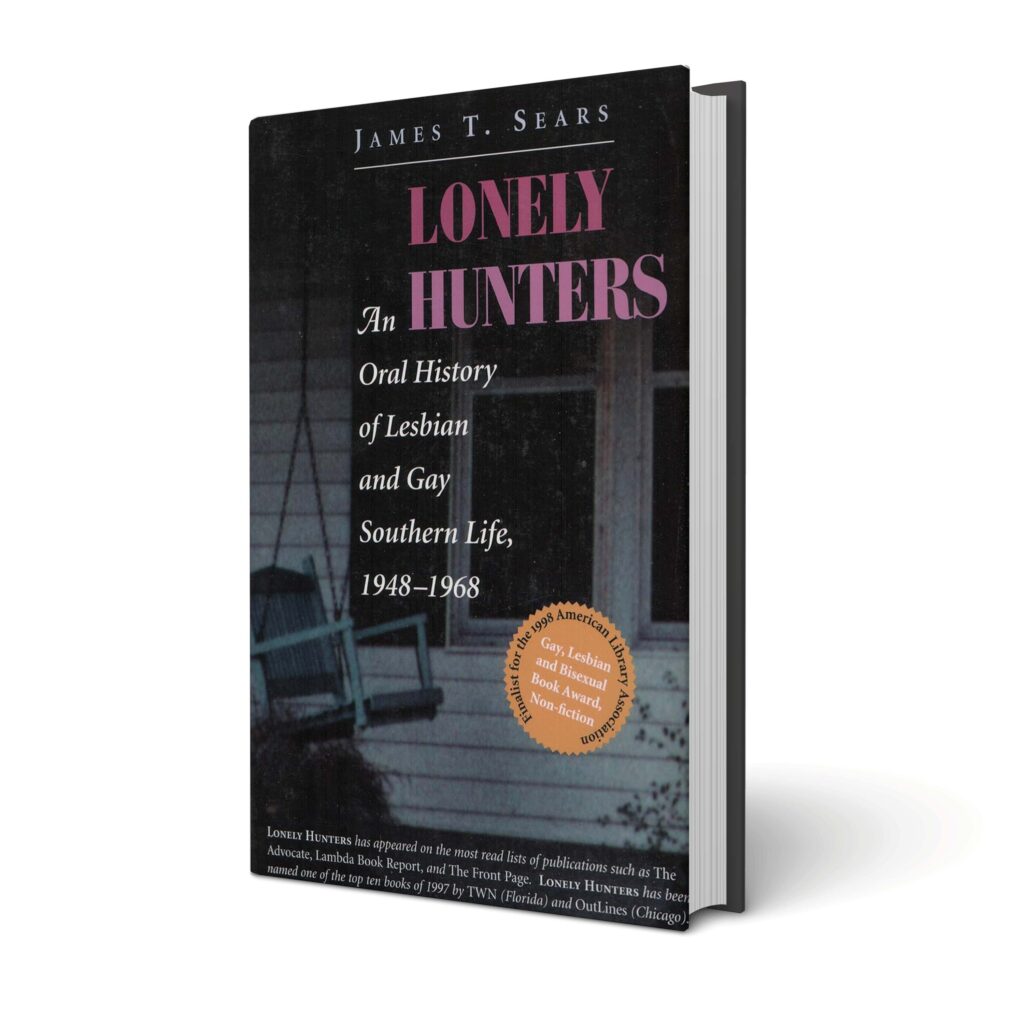

Howard has inspired many historical studies of the queer South, including Brock Thompson’s The Un-Natural State, contributor Jay Watkins’s Queering the Redneck Riviera, and La Shonda Mims’s Drastic Dykes and Accidental Activists. Each takes a distinctly regional and subregional approach—mapping, as Howard did, the movement of queer people across the landscape of the US South. As transformative as Howard’s work has been, though, it wasn’t the first. James T. Sears’s groundbreaking oral histories (Lonely Hunters; Rebels, Rubyfruit, and Rhinestones; and Growing Up Gay in the South) are essential records of queer life in the region. Early scholars of the queer South like Howard and Sears relied heavily on oral history work—which, for various reasons, including censorship and obscenity laws, has been indispensable to much of the historical work on queer communities in the United States—and oral history continues to be important both for community building and scholarship, as works like Gregory Samantha Rosenthal’s Living Queer History and Rae Garringer’s Country Queers evocatively show.

E. Patrick Johnson’s monumental set of oral history projects on Black gay men and queer women in the South—Sweet Tea and Black. Queer. Southern. Women., respectively—are part of a body of work that stakes the Black queer South as an inextricable part of what it means to be southern, to be queer, to be Black in America and in the South. Though not explicitly about the US South, Cookie Woolner’s The Famous Lady Lovers uses the archive to recount the lives of several southern Black women who loved other women. Queer histories of the US South upend the traditional historiography of LGBT life in the United States. Histories of labor, gay rights organizing, and government repression in Florida, such as Fred Fejes’s Gay Rights and Moral Panic, Jackie Blount’s Fit to Teach, and Karen Graves’s And They Were Wonderful Teachers, offer conflicting arguments about the chronology and temporal distinction of the gay rights movement in America, while also providing much-needed context for understanding our current cultural and political turmoil concerning lgbt inclusion in schools, libraries, and other public spaces.

Because of his American studies approach, Howard has inspired literature and cultural studies scholars as well. His edited collection, Carryin’ On in the Lesbian and Gay South, included essays on William Alexander Percy, Lillian Smith, and Charis bookstore in Atlanta. Literary studies of the queer South include Gary Richards’s Lovers and Beloveds, Michael Bibler’s Cotton’s Queer Relations, Jaime Harker’s The Lesbian South, and Heidi Siegrist’s All Y’all.And L. H. Stallings’s A Dirty South Manifesto focuses on Black southern life as a site of resistance through transgressive, nonnormative sexuality.

Queer southern authors are legion, and queer-focused books on these authors have also increased. For example, “Faulkner’s Sexualities,” a Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha conference, was quite controversial in 2007; by 2022, the conference hosted “Queer Faulkner,” featuring keynotes by Bibler, Harker, Siegrist, and Pip Gordon, author of Gay Faulkner. Tennessee Williams and Truman Capote have always had considerable critical attention, and other queer southern authors are beginning to get their due—notably Carson McCullers. Jenn Shapland’s My Autobiography of Carson McCullers, a creative-critical hybrid, was a finalist for the National Book Award in 2020.

Shapland’s book is a good reminder that writing about the queer South has a much longer history outside the academy. Back when new scholars of southern literature were trying to de-queer the South, queer southern artists were making that as difficult as they could. In the 1940s, writers whose work was labeled as “southern grotesque”—Tennessee Williams, Carson McCullers, Truman Capote—produced beautiful, haunting records of southern queer culture. In the 1970s and 1980s, southern lesbian feminists, many of whom were graduate students of literature, created their own queer southern genealogies. Feminary is the most famous of these interventions, but the collective that nurtured Minnie Bruce Pratt, Mab Segrest, and Cris South is but one of dozens of periodicals, collectives, and writers (all of which Jaime explores in The Lesbian South). Hooper’s work on the Southeastern Lesbian and Gay Conferences in the 1970s and 1980s explores another key site of creation and support that occurred largely outside of academic culture. Jaime is working with Michael Bibler to launch a reprint series with University of North Carolina Press called The Radical South, and many of these queer artists will be back in print soon.

The queer South continues to thrive and innovate and resist, far away from the academy. The immediate and effective resistance of drag performers in Tennessee in 2022, in response to antidrag legislation, is one of many shining examples of the vibrance of the queer South. Queer young adult and queer romance novels set in the South are firing the imagination of the next generation of queer southerners. The most famous author of queer new adult romance novels is Louisiana State University graduate Casey McQuiston, but she is far from the only one. The queer South continues to be resilient, hilarious, and nurturing, whether or not the academy notices.

New Directions in the Queer South

The contributions of the scholars and artists featured in this journal represent some of the best work expanding our understanding of the queer South, but their voices are only a few of the many speaking to the experiences of queer southerners. The trans* South, asexual South, and immigrant South each make their appearance in the pages of this issue. Joe Hatfield’s examination of Black trans life through the archives of Savannah’s famed Lady Chablis considers “the complex and often ambiguous nature of gender variability in the South.” Ellie Campbell’s “Seeing the Invisible” continues the longstanding tradition in queer southern studies of exposing how silences and elision function in the South to erase nonnormative sexualities, in this case those of asexual people.

For some queer southerners, their sexual or gender identity is incidental when compared to their immigration status, health, or economic situation. Joanmarie Bañez’s personal essay considers how the global pull of the urban South—Atlanta as metropole—draws families from across the globe, and in the process creates multiple valences of culture shock. The ever-present specter of hiv/aids continues to shape queer experiences in the region and across the globe, especially for those without the access to resources, education, and community necessary for care. We are proud to publish Robert W. Fieseler’s “Throwaway Boy,” a convicting piece of reportage tracing how sexual violence, addiction, and chronic illness converge in the life of one queer southerner. We would be remiss if we did not include another ever-present feature commonly attributed to the American South—religion. The paintings of Jimmy Wright—this issue’s featured artist—wrestle with the complicated feelings of home life and religious upbringing that many southern queer and trans people experience. Montia Daniels presents oral histories with Black queer women and nonbinary folks to think through how queer people engage with religiosity (or not) in what Flannery O’Connor famously called the “Christ-haunted” South.

Finally, we sought to gesture to the multiple geographies of the queer South through this issue. Rather than espouse a pan-southernism where the conditions for queer life are the same across the innumerable locales of the US South, we hope the works here demonstrate how varied the cultural forms of southern queer life are, from Rachel Gelfand’s Lexington, Kentucky, to Eric Solomon and Joshua Jacobs’s Atlanta, to Julio Capó’s Miami. Beyond the works that appear here, we received many other incredible pieces of scholarship and expression on the queer South. Our intent is to present a range not only of regions but also identities, approaches, and perspectives to serve as a jumping-off point for further queer southern studies. This is just the beginning.

Hooper Schultz is an oral historian and PhD candidate in History at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He earned his MA in southern studies and MFA in documentary expressions at the University of Mississippi. His research interests include the queer South, gay liberation and lesbian feminism, student activism, and queer oral history.

Jaime Harker is professor of English and director of the Sarah Isom Center for Women and Gender Studies at the University of Mississippi. She is the author of three monographs, most recently The Lesbian South: Southern Feminists, the Women in Print Movement, and the Queer Literary Canon. She is the coeditor of four essay collections