While working as part of the Student Action with Farmworkers program between his junior and senior year of college, Kyle was placed with Southern Migrant Legal Services, based in Nashville, Tennessee. Through his work, he met frequently with farmworkers contracted under the H-2A and H-2B guest worker programs across a five-state area, investigated farms historically known for labor violations, and researched legal precedent aiding and informing decisions in migrant farmworker cases. His stories are a collection of those interactions, both the lived experiences of his clientele and accounts from his firm’s previous work.

LUIS

Luis lived in the storage facility where his company stored old sweet potatoes from last year’s harvest, his bed among a large “bedroom” where about thirty other workers slept. The rank smell of rotting sweet potatoes lingered in the air, molding in their crates just a few feet away from where Luis slept at night. He told us everyone got used to the smell. But what he never got used to were occasional threats by snakes, scorpions, and spiders that lived in the crates and often came out at night. Luis hadn’t been bitten or stung (yet), nor did he know anyone who had, but he was waiting for the day when someone would eventually get hurt.

Basic amenities appeared scarce. Luis showed us the breakroom-turned-kitchen, which had two stoves—only one of which worked—and two refrigerators. But there was no real bathroom. Toward the back of the warehouse, the musky smell of rotting produce mingled with the pungent odor of raw sewage. The showering facilities where more than thirty workers lined up to bathe was nothing more than a spigot with a tarp fashioned around it. On the other side, raw sewage seeped up from the ground just inches away. Luis said it was difficult but there wasn’t anywhere else to go that he knew of and patron Jack had tried to “do good by them.” They would make do so long as they were provided with steady work and an honest paycheck.

SYLVIA

Sylvia loved the bright color of the tomatoes. There was something beautiful about plucking them from their vines each and every day. But that fruit often came at a high cost. Sylvia often spent an entire day picking tomatoes by the bushel, returning home with blisters, sores, and boils underneath her arms. The first couple months of work, she thought it was from repeatedly carrying a full basket to the truck. She was half-right. Hay una sintoma de las pesticidias. Her farm had been using very strong pesticides and herbicides to keep the tomatoes red. But she and other workers were never informed when the grower or crew leader spread the crops. There were no signs, just the hope that they would learn through word-of-mouth that it wasn’t safe to go into the fields. Once, Sylvia was directly sprayed with chemicals while she was picking tomatoes under the hot sun. In such cases, Sylvia and others hoped to get to Wal-Mart in time for ointment that would reduce the swelling, but they paid for it out of their own pockets and knew better than to complain. “Those who complain often don’t come back,” she said. She worked with people whose skin began to peel because of prolonged exposure—so burned and so raw that it shined like a ruby-red, ripe tomato.

MANUEL

Manuel spent nearly two decades of his life picking apples in the southeast to provide an honest wage for his wife back in Mexico. Each year, he came to the States on an H-2A visa, working for the same grower. And each year, Manuel was loaded with others into an overcrowded bus with loose tools and no seat belts every morning at 6 AM. By 7 AM, he was in the fields, climbing the tall trees and picking its fruits for a piece-rate; bruised pieces were thrown out. Workers, including Manuel, commonly fell out of the trees that they toiled in. Manuel complained after his first fall but never again. “What do you expect me to do about it?” He never received medical treatment, worker’s compensation, or even an extended hand. He was told to get back to work.

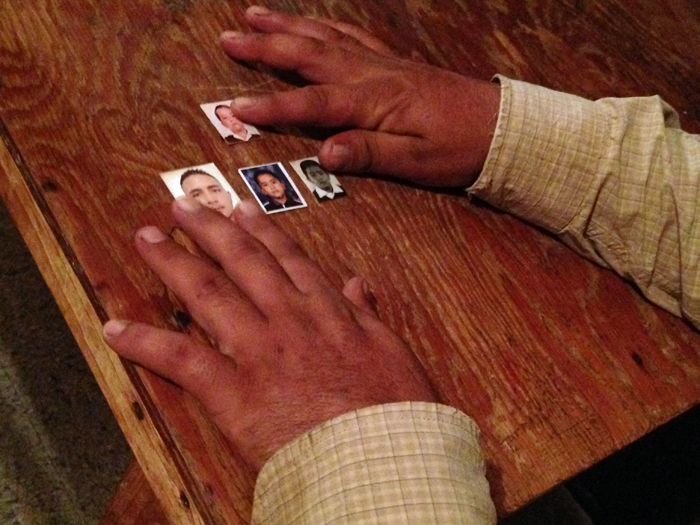

Manuel saved enough money for his wife and kids to safely cross the border into the states. Together, he and his wife worked in the fields for several years, holding on to each dollar they earned until they could open their own tienda. They raised a family on the earnings they received from providing other migrant farmworkers with basic goods. Their kids grew up as American citizens and, after Manuel and his wife put all three of them through college, two of them started their own restaurant chains in Nashville and Knoxville, Tennessee. To this day, Manuel works in his tienda, proud that his kids didn’t ever have to step foot in the fields and measuring his success by the distance between them. The further they are from the fields, the better off they must be. He’s never stocked apples in his store.

OCTAVIO

Octavio’s grower couldn’t bring in many of his H-2A workers on the date he promised because heavy rain in northern Louisiana ruined some of his sugar cane harvest and delayed his sweet potato planting. So Octavio, a crew leader, was tasked with bringing in undocumented and Texas-based workers during the wet season to harvest as much of the crop as possible. “It’s a shame that we don’t have our regular H-2A workers. The workers we have now do nothing but cause fights, get drunk, and destroy the housing. But at least we don’t have to pay them on the rainy days when they don’t work.” Normally, under the H-2A program, a grower has to pay at least ¾ of what they were expected to pay. No such law applies to Texas-based or undocumented workers.

Octavio was proud of the number of people he recruited from Texas and other southern states. They came ready to work but because of their undocumented status, the grower told them to go home, that he had no work for them. Dozens and dozens of workers arrived on buses only to be told to find their way back home. But southward, vast sugar cane fields lay ready for harvest with no workers in sight.

TENOLA

Tenola and his wife met working on the lines of the Mississippi catfish industry. Tenola primarily cleaned or cut fish, but on good days only had to assemble boxes. He grew up in Mississippi and found it strange to work next to migrant workers, doing the best he could to talk to them about work and his life. He loved to motion a hump over his stomach as he talked about his wife, lengthening and straining the word “pregnant” as if coworkers would understand it if he said it with an accent. Eventually they did.

He had a difficult relationship with his coworkers, whom he learned were making significantly more than him even though he had been working for the same company for over seven years. The H-2A program required they be paid a higher wage, though they didn’t get the same kind of benefits that a typical employee received. Tenola seemed satisfied with this answer, considering his meager dental and health insurance plans.

Tenola worked at double capacity and managed to leave an hour early, three hours after receiving the phone call from his wife.

One day at work Tenola heard from his wife, who told him she was having complications. Tenola thought the baby was on his way and rushed to get his work done. He asked his employers if he might be able to leave early from the plant if he finished cutting his quota of catfish early that day. He told his employer about the child and his phone call and they indicated to him that, so long as he got his work done, he could leave. So Tenola worked at double capacity and managed to leave an hour early, three hours after receiving the phone call from his wife. When he got home, he realized his wife was, in fact, having complications. He rushed her to the hospital only to find out it was too late. They had lost their first child.

The next day, Tenola returned to work. “What the hell do you think you’re doing here?” his manager yelled at him to get off the property immediately or he would have Tenola arrested. It was only until he talked to one of his coworkers that he found out his supervisor was upset about his leaving early the day before and, despite approving his absence, fired Tenola. Tenola no longer works for the company. Instead, his wife has taken his place on the line cutting and cleaning fish, assembling boxes on the good days. Tenola sits at home in his empty, silent house.

Kyle Warren calls Greenville, South Carolina, home and is a graduate of the University of South Carolina. After teaching fifth grade for two years in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Warren continues his work supporting Latinx and Hispanic communities as a teacher coach with the Teach For America program in the Greater Boston area.