“[The 2020 Democratic victory] was the culmination of a century and a half of efforts by Black citizens in Georgia to be able to vote, and the first election in the state’s history when the power of white conservatives and the presumption of white supremacy were decisively defeated.”

Before the enactment of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) in 1965, voting rules that were neutral in their language but functionally discriminatory made the Black vote in Georgia ineffective. By the time of the VRA, Black Georgians were 34 percent of the voting age population, but there were only three Black elected officials in the state, and those officials had been elected in the previous three years before the enactment of the VRA. Overall, less than a third of the eligible Black population was registered in the state, and in Georgia’s twenty-three counties with a Black voting-age majority, only 16 percent of African Americans were registered compared to 89 percent of white people. “This exclusion from the normal political process was not fortuitous; it was the result of two centuries of deliberate and systematic discrimination by the state against its minority population.”

In 1867, two years after the Civil War, Black males began voting in Georgia state elections. Between 1867 and 1872, sixty-nine African Americans were elected to either the state Constitutional Convention or the Georgia legislature. One man, Jefferson Franklin Long, briefly served from December 1870 to March 1871 as the first African American congressman from Georgia. But in September 1868, enough white Republicans in the Georgia legislature voted with the Democratic legislators to expel its thirty-three Black members. Violence accompanied these political tactics; in 1868, there were 336 reported cases of murder or assault against freedpeople. In January 1869, the Georgia State Supreme Court overturned the expulsions of the Black lawmakers, and, in January 1870, they returned to the legislature. That fall, however, Democrats gained a majority in the legislature, after which—though there was a Black member of the legislature as late as 1907—Black members of the legislature narrowed to a trickle. Populism and the Farmer’s Alliance became a major factor in Georgia politics in the late 1880s. Most Georgia Populists were not racial egalitarians, but they denounced race hatred and lynching, and they promoted enlightened and mutual self-interest as an economic strategy. The Populists also called for financial reforms and regulation of corporations, particularly the railroads. At the time, the Atlanta Constitution warned that maintaining white supremacy was more important than “all the financial reform in the world.” In Georgia, progressivism was, in the words of historian John Dittmer, “conservative, elitist, and above all, racist.”2

Georgia took additional steps to exclude Black voters from the franchise at the end of the nineteenth century. In 1890, the Georgia legislature passed a law ceding primary elections to party officials. The law kept political candidates from appealing to Black voters or building multiracial coalitions. In 1898, the Georgia Democratic Party adopted the use of a statewide primary, a popular progressive reform to remove politics from “smoke-filled back rooms.” But the adoption in Georgia was not a reform to bring in more democracy. In 1900, following the lead of South Carolina, Georgia became the second state to bar Black voters from participating in the Democratic Primary, under the pretense that the Democratic Party was a private “club” and only had to accept the patronage of its chosen “guests.” Because Georgia was a one-party Democratic state, this meant Black Georgians had no effective role in the state’s politics. The white primary was one of the central ways Georgia evaded the Fifteenth Amendment.3

The 1908 Felder-Williams bill broadly disenfranchised many Georgians but included a series of exceptions that would continue to allow most white voters to vote, such as: (1) having served in either the US or Confederate armies, (2) having descended from someone who had served in either the US or Confederate armies, (3) owning forty acres of land or five hundred dollars’ worth of property in Georgia, (4) being able to write or to understand and explain any paragraph of the US or Georgia constitution, or (5) being “persons of good character who understand the duties and obligations of citizenship.” Overall, the Felder-Williams bill’s literacy test, plus a property requirement and a cumulative poll tax, eliminated almost all existing Black voting.4

In 1917 Georgia adopted the county-unit system for the Democratic primary, a sort of state version of the electoral college. The Democratic primary was usually the only competitive election, and, under the county-unit system, every county was given twice the number of unit votes as it had representatives in the state house. Each of Georgia’s 159 counties had at least one seat in the legislature; no county had more than three. The county-unit system was not primarily directed against Black voters—who, until 1944, could not vote in the Democratic primary—but, as agitation for Black voting rights increased in the 1950s and early 1960s, segregationists realized malapportionment was an important tool for rendering the Black vote impotent. And so, by 1960, the three least populous counties in the state—Echols, Glasscock, and Quitman—had a combined population of 6,980, while Fulton County, containing most of Atlanta, had a population of 556,326. Collectively, however, the three smallest counties had a unit vote that equaled Fulton’s.5

In 1944, however, in Smith v. Allwright, the United States Supreme Court issued a landmark decision holding that political parties could not exclude Black Americans from participating in the party’s primary elections, thereby prohibiting the white primary system. One year later, in 1945, the United States District Court for the Middle District of Georgia ruled in King v. Chapman that the Muscogee County Democratic Executive Committee and the state of Georgia had violated the Fourteenth, Fifteenth, and Seventeenth Amendment rights of Primus E. King, a Black voter who had been turned away when he had attempted to vote in the Democratic Party’s primary in Columbus, Georgia, the previous summer. The judge, in part relying on Smith v. Allwright, found that despite Georgia’s attempts to make party primaries “purely private affairs,” primary elections were “by a law an integral part of the election machinery.”6

These cases, along with Governor Ellis Arnall’s decision not to attempt to “circumvent the [Allwright] decision,” and organizing efforts by groups like the naacp-backed All Citizens Registration Committee, led to a massive surge in voter registration in 1946, especially among Black voters. By the 1946 primary, 118,387 Black Georgians had registered to vote. According to the Jackson Progress-Argus of Jackson, Georgia, this was “by all odds the largest registration in Georgia’s primary.”7

This important progression in Black voter registration, however, was met by outright hostility from candidates in the 1946 gubernatorial election. For example, the race-baiting Democratic gubernatorial candidate in that election, Eugene Talmadge, campaigned on a platform of white supremacy and disenfranchisement, threatening that if the “Democratic White Primary is not restored and preserved,” Black voters, “directed by influences outside of Georgia,” would control the Democratic Party. As Talmadge menacingly warned, “wise Negroes will stay away from white folks ballot boxes.” Similarly, Marvin Griffin, a candidate for lieutenant governor, made white supremacy a cornerstone of his campaign and announced that he believed “the White Democratic Party should be kept white in Georgia, and that carpet baggers and scalawags should not be permitted to take over this state and destroy southern racial traditions.”8

In addition to the white primary, die-hard segregationists defended the county-unit system. For Peter Zack Greer, who was elected lieutenant governor of Georgia in 1962, “left-wing radicals and Pinks” were intent on unleashing the “bloc Negro vote in Atlanta.” Moderate segregationists expressed similar sentiments. Carl Sanders, elected Georgia’s governor in 1962, stated that eliminating the county-unit system would leave state government in the hands of “pressure groups or bloc votes”—the leading white Georgia euphemisms for Black voters—and the county-unit system would keep “liberals and radicals from taking over.”9

To prevent the overturning of the county-unit system, in 1962, the Georgia General Assembly made some modifications to increase the representation of Fulton County in the state senate from three to seven. At the same time, however, they created multimember at-large districts so the Black voters in a given county would always be outvoted and Fulton County’s state senators would be elected on an at-large basis. After this system was ruled unlawful, there were two majority-minority districts in Fulton County, one of which elected Leroy Reginald Johnson, the first African American to serve in a deep South state legislature in many decades.10

In 1963, the United States Supreme Court fully outlawed Georgia’s county-unit system in Gray v. Sanders, 372 U.S. 368 (1963), culminating in Wesberry v. Sanders, 374 U.S. 802 (1963), another case arising from Georgia in which the United States Supreme Court mandated equal apportionment for the upper houses of state legislatures and for congressional districts. As civil rights attorney Laughlin McDonald wrote, “[these cases were] not racial discrimination case[s], but its concept that voting districts must be composed of substantially equal populations was to prove one of the keys that opened the door to minority officeholding in Georgia.”11

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 would ultimately change the trajectory of voting rights for Black Georgians. Beyond statistical improvements in Black registration and elected officials, the VRA affected the tone of the political system itself. In 1974, Andrew Young, a civil rights activist with Southern Christian Leadership Conference who would be elected mayor of Atlanta in 1982, addressed the Association of Southern Black Mayors: “It used to be that Southern politics was just ‘n—-r’ politics: who could ‘outn—-r’ the other. Then you registered 10 to 15 percent in the community and folk would start saying ‘Nigra.'” When registration numbers went to 35 to 40 percent, “it’s amazing how quick they learned how to say ‘Nee-grow.'” And when registration increased to 70 percent of the Black votes registered in the South, “everybody’s proud to be associated with their black brothers and sisters.”12

Opposition to the VRA in Georgia was not limited to die-hard segregationists. The preclearance provision of the VRA, Section 5, brought the most objections. This provision required localities and states that had a history of discrimination in voting registration (primarily southern states like Georgia) to submit election changes that might adversely affect minority registration or voting strength to get prior approval by the Department of Justice (DOJ). In 1972, Governor Jimmy Carter, with a growing national reputation as a white southern moderate/liberal on race relations, denounced the preclearance provisions as “that discriminatory provision of the Voting Rights Act,” threatening (though not in the end carrying out) a walkout of southern delegates to the Democratic convention unless the party’s nominee, George McGovern, opposed reauthorization of preclearance.13

Preclearance was effective against many tactics used by white politicians in Georgia to prevent Black voters from electing candidates in Georgia. In 1964, in response to growing African American electoral strength, the Georgia General Assembly adopted a law that required many offices to be won by a majority vote and not a mere plurality. At the time, most of Georgia’s 159 counties operated under a plurality system. The majority vote system was adopted to prevent a Black candidate being “first past the post” against a divided white vote. Numbered posts (another method of at-large voting) were a way to discriminate against Black voters and Black candidates. When, for instance, there were three open positions for county commissioner, rather than electing the three candidates with the highest vote totals, candidates had to run specifically for seats No. 1, No. 2, and No. 3, diminishing the chances of electing Black candidates. Staggered voting was another technique used to limit Black voting strength; limiting the numbers of open seats at any one time made it more difficult to elect Black candidates, particularly if combined with at-large voting schemes. And the most common tactic, which was denied preclearance by the DOJ through 1982, was the annexation of territory by cities to decrease the percentage of the Black population.14

Many jurisdictions did not send in their proposed elections changes to the DOJ. Many jurisdictions in Georgia (such as Sumter County, Pike County, and Waynesboro) simply refused to comply with Section 5 objections. In Thomson, when faced with a Section 5 objection to majority voting, city officials encouraged the two white candidates to have an informal “run-off” to avoid splitting the white vote and thereby allowing the Black candidate to win. This practice, known as “cuing,” involves the endorsement by white community leaders of a specific candidate prior to the actual election, which, in the words of Laughlin McDonald, is “doing by indirection that which Section 5 expressly forbids.” In 1981, Julian Bond, a Georgia state senator, testified before the House of Representatives that there were over four hundred nonsubmissions of Section 5 notifications by Georgia jurisdictions.15

Overall, the number of VRA Section 5 preclearance challenges raised by private or federal suit show that Georgia was one of the most active and ingenious states in trying to prevent Black voting strength. From 1965 to 1981, the DOJ received a total of 34,798 voting changes submitted for preclearance under Section 5; DOJ ultimately objected to 815 of these proposed changes. Of those objections, 226, almost 30 percent, were from the state of Georgia. This figure far exceeds that of other states. Louisiana, for example, the state with the second-greatest number of objections, was the subject of only 136 objections.16

In the redistricting cycle after the 1980 census, the Georgia General Assembly again tried to limit Black voting strength in Atlanta. The Georgia General Assembly’s reapportionment plan contained white majorities in nine of the ten congressional districts, even though Georgia’s population at the time was nearly 30 percent Black. Julian Bond introduced a bill that would have made the Fifth Congressional District 69 percent Black. In response, the Chair of the Senate Reapportionment Committee criticized the proposal as one that would cause “white flight.” The Chair of the House Reapportionment Committee similarly criticized the proposal on the grounds that he was disinclined to draw “n—-r districts” or support “n—-r legislation.”17

Some members of the Georgia General Assembly stated they did not want to go back to their districts and “explain why I was a leader in getting a black elected to the United States Congress.” Bond’s proposal was predictably rejected, and the reapportionment plan drawn by the Georgia General Assembly was, as in the previous decade, rejected under Section 5 of the VRA. The Court then approved a new plan with a district that was 65 percent Black. Julian Bond and John Lewis, two old friends and comrades from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, vied for the seat; Lewis ultimately won. In 1980, of the eighteen Black Georgians elected to county governments—about only 3 percent of all office holders—sixteen were elected in majority Black districts or counties. As McDonald wrote in 1982, “blacks in Georgia’s majority white counties or districts, for all practical purposes, cannot get elected.”18

On the eve of the possible expiration of the VRA in the early 1980s, Georgia continued to show that an extension was necessary. In 1981, the New York Times summarized the status of Black voters in Georgia while the country debated the 1982 reauthorization of the VRA:

[In Georgia] 26.2 percent of the population is black, only 3.7 percent of the elected officials are black. The glitter of power in Atlanta, where two blacks are among the three frontrunners to succeed the city’s two-term black mayor, Maynard Jackson. In fifteen of the state’s twenty-two counties where blacks comprise a majority or close to it, no blacks serve on county commissions. It is not for want of trying; 34-year-old Edward Brown Jr. has twice run unsuccessfully for office in Mitchell Co. In Mr. Brown’s insistence, all-white poll officials and paper ballots greatly reduced his chances for winning. Testifying in a court case, Mr. Brown stated that it is difficult to win when whites as a matter of policy vote against blacks. Citing his defeats, he said that whites were transported to and from polling places by county sheriffs who urged them not to vote for Mr. Brown [because of his racial identity.]19

At the end of the decade, Georgia began another reapportionment cycle. Over the course of the 1990 redistricting cycle, the DOJ twice rejected the Georgia General Assembly’s state reapportionment plan, before finally approving the third submission. After the 1992 election, thirty-four African Americans were in the Georgia General Assembly, almost all of them from Black majority districts, almost all of whom owed their seats to litigation and to Section 5 of the VRA. In the 2000 redistricting cycle, for the fourth decade in a row, the Georgia General Assembly passed redistricting plans that would not survive preclearance. Specifically, the district court in the District of Columbia refused to preclear the General Assembly’s Senate plan, which decreased the Black voting age percentage in the districts surrounding Chatham, Albany, Dougherty, Calhoun, Macon, and Bibb Counties. Overall, the court found “the presence of racially polarized voting” and that “the State ha[d] failed to demonstrate by a preponderance of the evidence that the reapportionment plan for the State will not have a retrogressive effect.”20

In 2013, tactics to reduce Black voting strength were validated by the US Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County, Alabama v. Holder, 570 U.S. 529, which eliminated preclearance and made such tactics easier to employ. Georgia was no longer bound to submit any changes to its voting system through preclearance. In her dissent in that case, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg famously commented that “throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.” Within four days of Shelby County, the local Georgia press reported that the Augusta-Richmond County government (a consolidated city-county government) reopened discussions of moving its elections from November to July in an effort to limit voter turnout. Greene County, Georgia, approved a redistricting plan that would have eliminated one or two of the only Black districts on the county commission, a change that DOJ had previously refused to preclear. By the end of 2013, the Georgia General Assembly approved another plan for Greene County that reduced the Black voting age population in one district by 50 percent and placed the home of the other Black commissioner outside of the boundaries of the newly redrawn district. Without preclearance, the new redistricting plan went into effect.21

At the same time, in the early twenty-first century, the realignment between the Democratic and Republican parties was complete. The 2002 election, with the removal of the Confederate battle flag from the Georgia state flag looming in the background, proved to be a watershed moment for the state. For nearly half a decade, white voters in Georgia had been abandoning the Democratic Party for the Republican Party. When Republican Sonny Perdue defeated Democrat incumbent Roy Barnes as governor in 2002, the election “broke a Democratic stronghold on the Georgia governorship that had kept the gop out since Reconstruction.” In the 2004 election, Republicans also won the majority of House seats, shifting control of the legislature.22

But there was one thing that Georgia Republicans could not control or prevent: the explosive growth of Atlanta, the Atlanta Metro area, and racial minorities in the state of Georgia. Unlike other southern states, where the Black population as a percentage of the whole population has declined in recent decades, Georgia’s population has substantially increased from 1970 to the present, specifically from 25.6 percent to 31 percent in 2020. As of 2021, non-Hispanic whites (excluding African Americans, Latino Americans, and Asian Americans) are a minority of Georgia’s population, the only state in the southeast for which this is true. (Not even in Florida, with its large Latino population, is this the case.)23

Most of this growth has been in the Atlanta metropolitan area, which, in 2020, was the ninth-largest metropolitan area in the country. Between 1970 and 2020, Atlanta’s Metropolitan Statistical Area, as defined by the Census Bureau, grew from 1,716,628 (37 percent of Georgia’s population), to 6,089,815 (57 percent of the state’s population). If the growth of suburban Atlanta had been a key part of the growing modern conservatism, this has changed in recent decades, as Black people and other racial minorities have moved to inner-ring suburbs.24

The growth and demographic shifts in the four core metro Atlanta counties—Cobb, DeKalb, Fulton, and Gwinnett—is even more striking, growing from 1,292,121 in 1970 to 3,554,303 in 2020. One-third of Georgia’s population is contained in these four counties, and in all four counties, non-Hispanic whites are a minority. In a state where Biden won by a mere 0.23 percent, he won the four counties by a plurality of almost 600,000 votes. Anything that might dampen voter turnout in these four counties could have a decisive impact on statewide races. As the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights observed in May 2021, “racial demographics determine to a significant extent who is elected in the Georgia General Assembly.”25

As in Georgia’s past, modern-day elected officials, law enforcement officers, and political activists continue to harass and intimidate Black voters and candidates. Nowhere was this more obvious than in Quitman, Georgia—a predominantly Black city in a predominantly white Brooks County. In 2010, more than fourteen hundred Black voters participated in the Democratic primary election for school board. In response, then-Secretary of State Brian Kemp (in cooperation with the Georgia Bureau of Investigation) opened a formal investigation into the 2010 election in Quitman. The Black leaders, who became known as the “Quitman 10+2,” were collectively charged with 102 felony counts that were subsequently blocked. One of those indicted later said that “the message sent to our citizens was, if you don’t want the gbi to come visiting and put you in jail, you better not vote.”26

In 2014, in comments to a group of Republican voters in Gwinnet County, Kemp connected minority voting rights and election victories when he remarked that “the Democrats are working hard … registering all these minority voters that are out there and … if they can do that, they can win these elections in November.” But preclearance itself was never a panacea. With Georgia’s 159 counties and hundreds of local jurisdictions (part of the over thirty thousand jurisdictions in the preclearance states), it was impossible to keep track of every local jurisdiction, many of which did not file voting-related changes with the DOJ. At-large, countywide, or citywide voting has been historically one of the main tactics used to curb voting rights strength. Preclearance had hardly ended the practice. In December 2013, of Georgia’s 159 counties, thirty-four elected all county commissioners at-large. One of those was Baker County, where almost half of the population was Black, but all of the county commissioners were white. A former Baker County Commissioner, Robert Hall, was quoted in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution as saying, “We don’t have many Blacks in Baker County that are landowners and taxpayers and responsible.” This trend is not unique to Baker County. In December 2013, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported that, across Georgia, while “more than half of majority-black counties have majority-white commissions,” “no majority-white county has a majority-black commission.” These types of election arrangements continue to disadvantage Black Georgians. As of 2013, in Georgia, white Georgians were 59 percent of registered voters, but accounted for 77 percent of the commissioners, while Black Georgians were 30 percent of registered voters, but only 22 percent of county commissioners.27

Overall, the end of preclearance has opened the doors to all manner of voter suppression and disenfranchisement, largely directed against minorities. The US Commission on Civil Rights found that, as of 2018, among the former preclearance states, only Georgia had adopted all five of the most common restrictions that impose roadblocks to minority voters, including (1) voter ID laws, (2) proof of citizenship requirements, (3) voter purges, (4) cuts in early voting, and (5)

widespread polling place closures. Senate Bill 202, passed by the Georgia General Assembly in 2021, which the US Department of Justice has challenged under Section 2 of the VRA, still has some possibility of success against laws with the effect and intent of making it more difficult for Black Georgians to vote.28

By 2019, the Leadership Conference Education Fund found that Georgia had closed over two hundred polling locations in Georgia since the Shelby County decision despite adding millions of voters to the voter rolls. By 2019, “eighteen counties in Georgia closed more than half of their polling places, and several closed almost 90 percent.” In 2020, the nine counties in metro Atlanta that had nearly half of the registered voters (and the majority of the Black voters in the state) had only 38 percent of the state’s polling places. Unsurprisingly, because of the fewer polling places, the lines at majority-Black polling places increased, and sometimes dramatically so. In the June 2020 primary, for example, waiting times to vote in some metro Atlanta suburbs, such as Union City (a subdivision that is 88 percent Black majority) was as long as five hours. Union City was not an outlier. A 2020 study found that “about two-thirds of the polling places that had to stay open late for the June primary to accommodate waiting voters were in majority-Black neighborhoods, even though they made up only about one-third of the state’s polling places.”29

One of the most insidious forms of voter disenfranchisement by Georgia in recent years, which disproportionately affected minority voters, was Georgia’s “exact matching” procedures. As the Northern District of Georgia has explained, Georgia’s exact match procedures policies meant that when a prospective voter submitted a voter registration application, Georgia would check the registration against its Department of Driver Services or files from the Social Security Administration. If the applicant’s information did not match those files exactly, “then the voter registration application is placed in ‘pending status,’ and the person may not vote until the person corrects the information.” The burden is on the applicant to take the next steps to correct any information. Exact-match legislation in Georgia was originally passed by the Georgia General Assembly in 2008 and was originally blocked under preclearance, though it received DOJ approval in 2010 when the Secretary of State agreed to place “safeguards” on the practice. As the DOJ later argued, however, it is not clear if those safeguards were ever used. After Shelby County, Georgia operated the exact-match procedures without strict safeguards. Under the Department of Driver Services match, Black Georgians, who made up only 28.2 percent of the registered voters, were 53.3 percent of those voters whose applications were canceled or placed in pending status. By contrast, non-Hispanic whites, who were almost half of registered voters in Georgia, made up a far lower 18.3 percent of those applications that were canceled or pending. By July 2018, 51,111 voters’ applications were suspended and placed in the “pending voter” category, of whom 80 percent were either African American, Hispanic/Latino, or Asian. By 2019, Georgia agreed to largely abandon its exact-matching process, and, in litigation, ended the most egregious practices.30

After Shelby County, Georgia officials also made more systematic efforts to purge the voting rolls in ways that particularly disadvantaged minority voters and candidates. Between 2012 and 2018, for example, then-Secretary of State Kemp removed 1.4 million voters from the eligible voter rolls. In a single day in 2017, Georgia removed over five hundred thousand names from the list of 6.6 million registered voters, which, according to election law experts, might be the “largest mass disenfranchisement in U.S. history.” While there can be legitimate reasons to drop names from the eligibility rolls (such as for a voter who is deceased, who has moved, or who has a felony conviction), the vast majority of those purged were those who simply had not voted in intervening years. An investigative journalism group run by Greg Palast found that, of the approximately 534,000 Georgians whose voter registrations were purged between 2016 and 2017, more than 334,000 still lived where they were registered. The voters were given no notice that they had been purged. Palast sued Kemp, claiming over three hundred thousand voters were purged illegally. Kemp’s office denied any wrongdoing. The purges were significantly overrepresented in precincts that overwhelmingly voted for Stacey Abrams, the Black Democratic candidate.31

In that 2018 gubernatorial election, Republican Secretary of State Brian Kemp ran against Abrams. Because Kemp would supervise the election, and because he was accused of voter purges, Abrams asked Kemp to step down; he didn’t. The election was close. Kemp won 1,978,408 to 1,923,685, a difference of some fifty-five thousand votes. In its aftermath, Abrams founded Fair Fight Action and worked extensively to register new voters. Fair Fight Action contributed to the closeness of the 2020 election, in which both senate seats and the presidency were on the ballot.

The 2020 presidential and senatorial elections in Georgia and their subsequent specious contestation will undoubtedly be remembered as among the most notorious in the state’s history. They had profound national implications. Because of his efforts to interfere with the counting and certification of the election results, Donald Trump, the only former president to be indicted for a felony, has been indicted twice: in Fulton County, for his actions in Georgia, and in a federal indictment in Washington, for his actions in Georgia and in other states. But to focus on the indictments is to miss what is most remarkable about the election. As reporter Greg Bluestein wrote, “Georgia turned purple and broke the monopoly on Republican power.” Donald Trump lost. He had won Georgia by more than 5 percent of the vote in 2016; Mitt Romney had won Georgia by more than 8 percent in 2012. Moreover, in the two senatorial elections, Georgia elected, for the first time in its history, an African American man, Raphael Warnock, to the US Senate, along with a liberal Jewish candidate, Jon Ossoff. To be sure, the election was close. Joseph Biden, the presidential winner in Georgia, received 49.47 percent, narrowly defeating Donald Trump, who received 49.25 percent, with Biden winning by 11,799 votes. Nonetheless, it was the culmination of a century and a half of efforts by Black citizens in Georgia to be able to vote, and the first election in the state’s history when the power of white conservatives and the presumption of white supremacy were decisively defeated.32

White racism and the efforts to suppress or curb Black voting are supple and protean. White voters and leaders react to changing circumstances to maintain superiority, and the loss in 2020 brought about a so-called white backlash. As Lawrence B. Glickman has argued, the term white backlash is a misnomer because it assumes backlashers are reacting to events rather than shaping them, as if their reactions were Pavlovian, an automatic and understandable response to a stimulus—such as “Black militants caused the white backlash”—rather than seeing the upholders of Jim Crow as the most powerful historical agents.33

Much talk of structural racism in recent years sees racism as personal or hardwired into many of the country’s institutions. And yet, institutions of white supremacy are not set in stone; they are fluid and malleable. In the history of the post–Jim Crow South, conservative white southerners discovered they could maintain their power without de jure segregation, and they found other ways to curb and neutralize the growing political and voting strength of Black Americans. What has remained unchanged is the goal: to maintain white supremacy and power at all costs. This maintenance has involved redistricting and gerrymandering to dilute Black voting strength, photo ID requirements in polling places, challenging voting registrations on spurious grounds, manipulating absentee voting availability, and other strategies. Conservative white southerners also adopted the rhetoric of their opponents, calling Black Democrats and their supporters “racist.” In the 2022 Georgia Senate race, white political leaders supported a conservative Black candidate (Herschel Walker, who lost) in an effort to maintain their hegemony. White conservative control over Georgia’s politics has been challenged—and, in 2020, its opponents scored a notable victory—but it is hardly broken.

While none of Trump’s or his allies’ efforts succeeded in altering the outcome of the 2020 presidential vote in Georgia, they did create tremendous pressure among Georgia Republicans to change the election laws that led to Biden’s victory in the state. As Steve Gooch, Georgia Senate Republican Whip, said in early December 2020, “We have totally lost confidence in our election system this year.” Even Republicans who did not support Trump’s fraud allegations, notably Secretary of State Raffensperger and Governor Kemp, supported legislation to correct flaws in Georgia’s electoral procedures that they claimed were nonexistent. The result was SB 202. Kemp stated after its passage that “significant reforms to our state were needed. There’s no doubt there were many alarming issues with how the election was handled, and those problems, understandably, led to a crisis of confidence in the ballot box here in Georgia.” Geoff Duncan, the Republican lieutenant governor of Georgia, stated that SB 202 was “really the fallout from the ten weeks of misinformation that flew from former president Donald Trump.”34

The 2024 presidential election in Georgia will again be close. A major challenge to democratic practice will be assuring that every eligible voter who wishes to participate in the election will be allowed to do so.

Orville Vernon Burton is the inaugural Judge Matthew J. Perry Distinguished Chair of History and Professor of Global Black Studies, Sociology, and Anthropology, and Computer Science at Clemson University. He is the coauthor, with Armand Derfner, of Justice Deferred: Race and the Supreme Court. In 2022, he received the Southern Historical Association’s John Hope Franklin Lifetime Achievement Award.

Peter Eisenstadt is the author or editor of over twenty books, including Encyclopedia of New York State and Rochdale Village: Robert Moses, 6,000 Families and New York City’s Great Experiment in Integrated Housing. With Walter Fluker, he was the associate editor of the five volumes of The Papers of Howard Washington Thurman and coeditor of the four volumes of Walking With God: The Sermon Series of Howard Thurman.

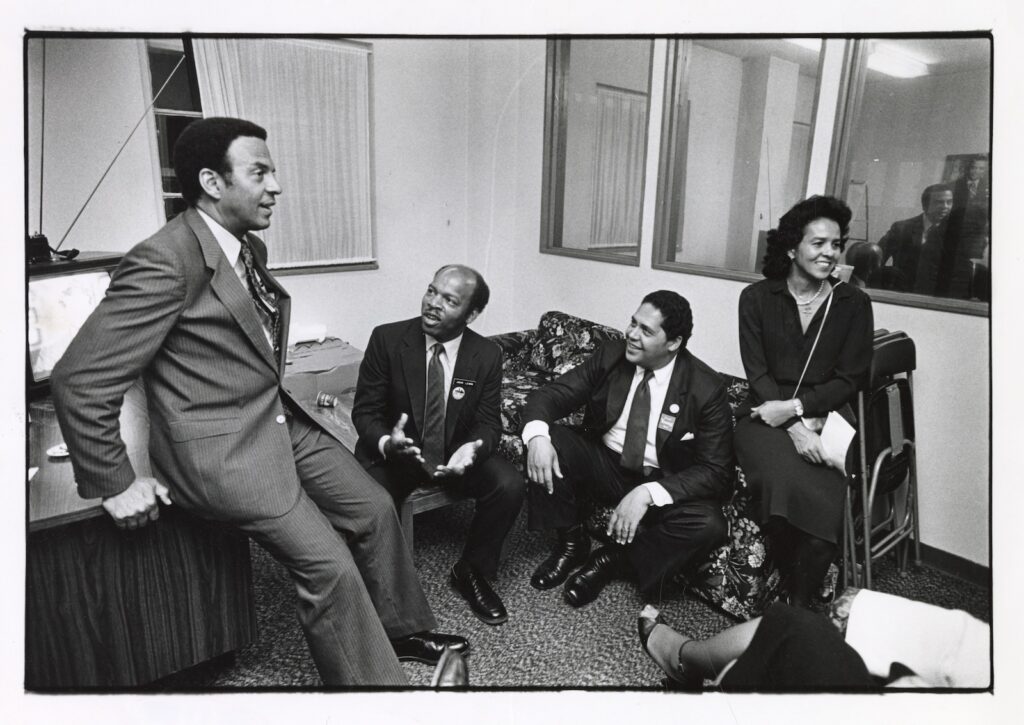

Header image: Georgia Democratic candidates for US Senate Raphael Warnock (left) and Jon Ossoff (right) gesture toward a crowd during a campaign rally in Marietta, Georgia, November 15, 2020. AP Photo/Brynn Anderson.

NOTES

- US Commission on Civil Rights, Political Participation: A Study of the Participation by Negroes in the Electoral and Political Processes in Ten Southern States since the Passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1968), 216–217, 232–239; Laughlin McDonald, Michael B. Binford, and Ken Johnson, “Georgia,” in Quiet Revolution in the South: The Impact of the Voting Rights Act, 1965–1990, ed. Chandler Davidson and Bernard Grofman (Princeton University Press, 1994), 67–102, 409–413, quotation on p. 67.

- Laughlin McDonald, A Voting Rights Odyssey: Black Enfranchisement in Georgia (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 37; John Dittmer, Black Georgia in the Progressive Era, 1900–1920 (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1977), 214.

- Numan V. Bartley, The Creation of Modern Georgia (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1990), 149; GA History, “White Primary Ends,” accessed January 19, 2024, http://gahistorysms.weebly.com/white-primary-ends.html; McDonald, Voting Rights Odyssey, 38.

- McDonald, Voting Rights Odyssey, 41.

- Between 1872 and 1950, the Democratic candidate won every statewide race. See McDonald, Voting Rights Odyssey, 81.

- Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944); King v. Chapman, 62 F. Supp. 639 (M.D. Ga. 1945); Chapman v. King, 154 F.2d 460 (5th Cir. 1946); Chapman v. King, 327 U.S. 800 (1946); “Judge Rules Negroes May Vote,” Atlanta Constitution, October 13, 1945; “Georgia Reform Faces Test in Hot Primary,” Sunday News (Lancaster, PA), July 14, 1946; Ronald H. Bayor, Race and the Shaping of Twentieth-Century Atlanta (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 34.

- McDonald, Voting Rights Odyssey, 49; “Total Registration in Georgia May Reach Million When Deadline Falls,” Jackson Progress-Argus (Jackson, GA), June 20, 1946; “118,387 Qualified to Vote in Georgia Primary Election,” The Plaindealer (Kansas City, KS), July 19, 1946.

- “Georgia CAN Restore the Democratic White Primary and Retain County Unit System,” Forsyth County News (Cummings, GA), July 4, 1946; James C. Cobb, The South and America Since World War II (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 7; Houston Home Journal (Perry, GA), May 30, 1946; Kathy Lohr, “FBI Re-Examines 1946 Lynching Case,” July 25, 2006, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5579862.

- McDonald, Voting Rights Odyssey, 82–83.

- McDonald, Voting Rights Odyssey, 86–89.

- McDonald, Voting Rights Odyssey, 80, 89–90.

- Jack Bass and Walter DeVries, The Transformation of Southern Politics: Social Change and Political Consequence since 1945 (New York: Basic Books, 1976), 47; David S. Broder, Changing of the Guard: Power and Leadership in America (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1980), 367. The slurs were spelled out in full in the original source.

- Rick Perlstein, “True Colors: Was Jimmy Carter an Outlier?,” The Nation, October 18/25, 2021.

- McDonald, Voting Rights Odyssey, 92–102; J. Morgan Kousser, Colorblind Injustice: Minority Voting Rights and the Undoing of the Second Reconstruction(Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 197–242. The Georgia city of Jackson, for example, used annexation to limit Black voting strength until enjoined in 1981. Laughlin McDonald, Voting Rights in the South: Ten Years of Litigation Challenging Continuing Discrimination against Minorities; A Special Report from the American Civil Liberties Union (New York: American Civil Liberties Union, 1982), 52–53, 60.

- Laughlin McDonald, Voting Rights in the South, 60; “Testimony of Julian Bond, State Senator from Georgia, Extension of the Voting Rights Act: Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional Rights of the Committee of the Judiciary,” May–July 1981.

- “Testimony of Julian Bond,” 20–25.

- McDonald, Voting Rights Odyssey, 168–173. The slurs were spelled out in full in the original source.

- McDonald, Voting Rights Odyssey, 168–173; McDonald, Voting Rights in the South, 40–43.

- Reginald Stuart, “Once Again a Clash Over Voting Rights,” New York Times, September 27, 1981. The original source quoted Brown as saying county sheriffs urged a vote against him because “he’s a n—-r,” with the term spelled out in full.

- McDonald, Voting Rights Odyssey, 211–224; Georgia v. Ashcroft, 195 F.Supp. 2d 25, 94 (D. D.C. 2002), affirmed, King v. Georgia, 537 U.S. 1100 (2003).

- Shelby County, Alabama v. Holder, 570 U.S. 529 (2013); Harry Baumgarten, “Shelby County v. Holder‘s Biggest and Most Harmful Impact May Be on Our Nation’s Smallest Towns,” Harry Baumgarten, Campaign Legal Center, June 20, 2016, https://campaignlegal.org/update/shelby-county-v-holders-biggest-and-most-harmful-impact-may-be-our-nations-smallest-towns.

- Danny Hayes and Seth C. McKee, “Booting Barnes: Explaining the Historic Upset in the 2002 Georgia Gubernatorial Election,” Politics and Policy 32 (December 2004), 1.

- Wikipedia, s.v. “Historical Racial and Ethnic Demographics of the United States,” last modified December 4, 2023, 02:43, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historical_racial_and_ethnic_demographics_of_the_United_States. There are only a handful of states with lower percentages of non-Hispanic whites than Georgia in the 2020 census. Hawaii, California, New Mexico, Texas, and Nevada are states that have long had high numbers and percentages of Latino/Hispanic, Native American, or Asian/Pacific Islanders. Washington, DC, until recently, had a Black majority population, and there has been a recent overflow of its Black population into suburban Maryland. The comparison with other southern states is striking. The non-Hispanic white percentage in Alabama, North Carolina, and South Carolina is over 60 percent, and over 55 percent in Virginia, Louisiana, and Mississippi. The southern state closest to Georgia is Florida, whose population in 2020 was 53.3 percent white non-Hispanic.

- Wikipedia, s.v. “Metro Atlanta,” Wikipedia, last modified December 13, 2023, 11:00, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metro_Atlanta.

- US Department of Commerce, Population of States and Counties of the United States, 1790–1990 (Washington, Government Printing Office, 1996), 34–42; “2020 Census,” Georgia Governor’s Office of Planning and Budget, https://opb.georgia.gov/census-data/2020-census-results2020. In the 2020 census, the figures for the white, non-Hispanic population in the four counties were Cobb (48.19 percent), DeKalb (28.24 percent), Fulton (37.95 percent), and Gwinnett (32.45 percent); source: the four Wikipedia entries on the four counties. Biden won the four counties by a plurality of 594,757 votes. “Georgia Presidential Election Results,” Politico, January 6, 2022. Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights, The Central Role of Racial Demographics in Georgia Elections: How Race Affects Elections for the Georgia General Assembly (May 2021).

- Jon Ward, “How a Criminal Investigation in Georgia Set an Ominous Tone for African-American Voters,” Yahoo!News, August 6, 2019, https://news.yahoo.com/how-a-criminal-investigation-in-georgia-set-a-dark-tone-for-african-american-voters-090000532.html; Ariel Hart, “Voting Case Mirrors National Struggle,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, December 13, 2014; Gloria Tatum, “Voter Fraud Charges from 2020 Fizzle in Quitman, South Georgia,” Atlanta Progressive News, September 18, 2014, http://atlantaprogressivenews.com/2014/09/18/voter-fraud-charges-from-2010-fizzle-in-quitman-south-georgia/.

- Steve Benen, “Georgia GOP Official Express Concerns About ‘Minority Voters,'” MSNBC, September 11, 2014, https://www.msnbc.com/rachel-maddow-show/georgia-gop-official-express-concerns-about-minority-voters-msna410401; Ariel Hart, Jeff Ernsthausen, and David Wickett, “Racial Politics Not So Clear Cut,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, December 9, 2013.

- US Commission on Civil Rights, An Assessment of Minority Voting Rights Access in the United States: 2018 Statutory Enforcement Report (Washington, 2018), 369. The restrictions on naturalized citizens were later curtailed; see “Georgia Must Ease Rules Proving Citizenship, Judge Says,” PBS News Hour, November 2, 2018, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/georgia-must-ease-rule-for-voters-proving-citizenship-judge-says.

- The Leadership Conference Education Fund, Democracy Diverted: Polling Place Closures and the Right to Vote (September 2019), 31; Stephen Fowler, “Why Do Nonwhite Georgia Voters Have to Wait in Line for Hours? Their Numbers Have Soared, and Their Polling Places Have Dwindled,” ProPublica, October 17, 2020, https://www.propublica.org/article/why-do-nonwhite-georgia-voters-have-to-wait-in-line-for-hours-their-numbers-have-soared-and-their-polling-places-have-dwindled; Mark Niesse and Nick Thieme, “Fewer Polls Cut Voter Turnout Across Georgia,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, December 15, 2009.

- Georgia Coal. for People’s Agenda, Inc. v. Kemp, 347 F. Supp. 3d 1251, 1255–56 (N.D. Ga. 2018); Stacey Abrams, Our Time Is Now: Power, Purpose, and the Fight for a Fair America (New York: Henry Holt, 2020), 58–61; Carol Anderson, One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression Is Destroying Our Economy (New York: Bloomsbury, 2018), 78–81; Aja Arnold, “Ex Post Facto: Abrams v Kemp,” The Mainline, May 11, 2020, https://www.mainlinezine.com/ex-post-facto-abrams-vs-kemp-2018/; Brentin Mook, “How Dismantling the Voting Rights Act Helped Georgia Discriminate Again,” Bloomberg City Lab, October 15, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-10-15/how-georgia-s-exact-match-program-was-made-possible; Stanley Augustin, “Georgia Largely Abandons Its Broken ‘Exact Match’ Voter Registration Process,” Lawyers’ Committee For Civil Rights, April, 5, 2019, https://www.lawyerscommittee.org/georgia-largely-abandons-its-broken-exact-match-voter-registration-process/.

- Alan Judd, “Georgia’s Strict Laws Lead to Large Purge of Voters,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, October 27, 2018; Angela Caputo, Geoff Hing, and Johnny Kaufman, “After the Purge: How a Massive Voter Purge Affected the 2018 Election,” APM Reports, October 29, 2019, https://www.apmreports.org/story/2019/10/29/georgia-voting-registration-records-removed.

- Greg Bluestein, Flipped: How Georgia Turned Purple and Broke the Monopoly on Republican Power (New York: Viking, 2022).

- Lawrence B. Glickman, “White Backlash,” in Myth America: Historians Take on the Biggest Legends and Lies About Our Past, ed. Kevin M. Kruse and Julian E. Zelizer (New York: Basic Books, 2022), 211–224.

- Maya T. Prabhu and David Wickert, “GOP Senators Say They Will Push Election Changes in 2021,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, December 3, 2020; “Marching Backward Into History,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, March 28, 2021; Tom Porter, “Giuliani’s Baseless Voter-Fraud Conspiracy Theories Helped Bring About Georgia’s Restrictive Voting Law, Lieutenant Governor Says,” Inside, April 8, 2021, https://www.businessinsider.in/politics/world/news/giulianis-baseless-voter-fraud-conspiracy-theories-helped-bring-about-georgias-restrictive-voting-law-lieutenant-governor-fail. Duncan refused to call SB 202 to the floor.