The more each of us can imagine what it would feel like to live in others’ lives, the better, I think. And the more inclusively we can all think, the more we can collectively begin to work for a world that is more just, more equitable, and in every sense healthier for all. If this crisis gets us thinking in those terms, perhaps we can salvage something worthwhile out of this calamity.

In her 2008 book Contagious: Cultures, Carriers, and the Outbreak Narrative (Duke UP), Priscilla Wald identified a cultural narrative of emerging infections circulating in scientific, journalistic, and fictional accounts of infectious disease that she calls the “outbreak narrative.” This narrative, which follows a formulaic plot of disease emergence, identification, and containment, gained popularity in the 1990s and has continued to shape how scientists and the public alike understand catastrophic epidemic disease. It has material consequences that range from stigmatizing groups or locales to changing economies and affecting survival rates. In the midst of a global pandemic, the outbreak narrative informs not just how we talk about infectious disease but also how we respond to it. On April 2, 2020, Kym Weed spoke with Wald by phone to learn more about what the outbreak narrative can teach us about the COVID-19 pandemic, from the interconnectedness that infectious disease calls up the modes of disease prevention that it precludes.

Kym Weed: The outbreak narrative [is] really at the heart of Contagious and some of your work on disease emergence. Could you take a moment to explain what the outbreak narrative is and how you identified it in the first place?

Priscilla Wald: In the mid-’90s, [I became] interested in Typhoid Mary because she came up in some of the research I was doing. Typhoid Mary was . . . an Irish immigrant named Mary Mallon who worked as a cook and she was the first identified healthy carrier of typhoid. [She] was a really important figure for public health because they were trying to figure out how disease spread—bacteriology was still a pretty new science. The idea [that] somebody who did not have a disease—who had never had a disease—could still transmit disease was a really important discovery for public health.

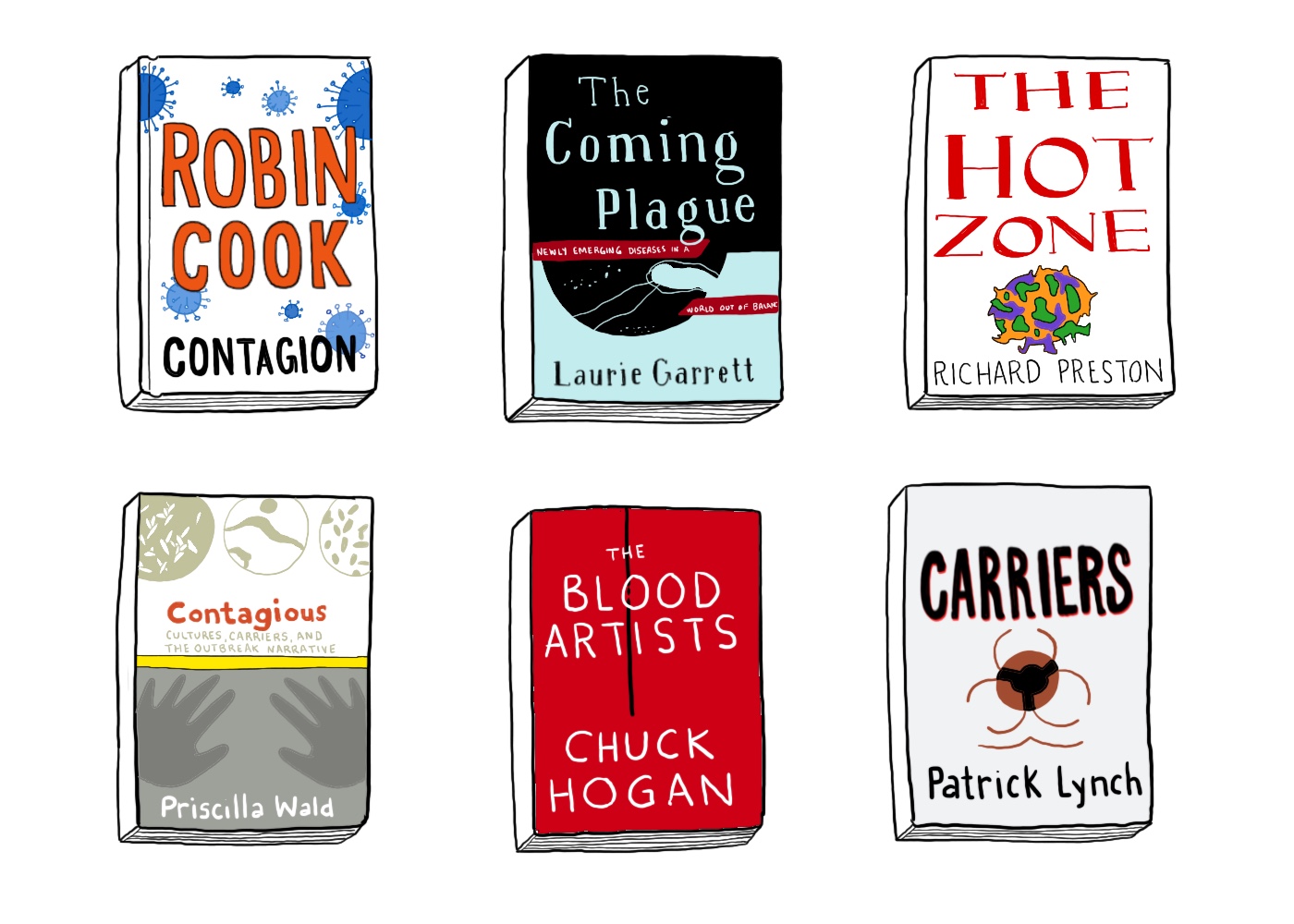

I got very interested in that figure, and at the same time—this was the mid-’90s—I went to the film Outbreak. I was really struck by the film. It got me interested in reading about this weird, new hemorrhagic fever that the film was about, and I picked up The Hot Zone [1994], Richard Preston’s journalistic account of an Ebola threat that ended up being simian and not transmittable to humans. I read Laurie Garrett’s The Coming Plague [1994] and began to ask myself, why is everybody so obsessed with this idea of disease emergence? What is it exactly? I began to notice some similarities in the way the stories of these new emerging infections of hemorrhagic fevers were being told and in the story of Typhoid Mary and I began to wonder what was going on.

My research led me to a 1989 conference [the Conference on Emerging Viruses at the National Institutes of Health], which was at the end of the decade when HIV had made the rounds around the globe, which I had lived through in New York City. This conference included infectious disease specialists, epidemiologists, people who were interested not just in HIV but in a whole spate of really devastating communicable diseases that were newly identified—microbes human beings hadn’t encountered: Ebola, Bolivian hemorrhagic fever. Hantavirus wasn’t new, but it had re-emerged recently. HIV, obviously.

They identified these with the term “emerging infections” or “emergent diseases.” They published several collections of essays out of this conference, along with Garrett’s book and other journalistic pieces. This, for me, was the beginning of this thing I call the outbreak narrative: what they were trying to argue at this conference was that this . . . phenomenon was caused by, or the result of, globalization and development practices. The population was growing and looking for new habitations, and new places were being developed, so human beings were coming into contact with microbes we hadn’t encountered before, to which there was no herd immunity. We were immunologically naïve. At the same time, [the narrative constructed by these conference participants said that] the world was getting smaller. We were increasingly interconnected because of trade and travel and all kinds of things. A disease that popped up in some new place that was remote from cities made it very quickly into the cities because people could travel more quickly and then into the world at large from any given city. What they said is [that] we have to not just think about this as a problem for medical science and epidemiology, we have to think about this in much broader terms as a problem of globalization and development and we have to change our development practices. We have to think about spotting these problems more quickly, before they get into this worldwide web, you could say, comprised of human beings and plants and animals and goods circulating together.

That was the story they wanted told. Starting with the science publications—through metaphor and narrative account—the story that they were telling that got picked up by journalists and eventually by popular fiction and film had a particular geography. It always began in the global South and migrated to the global North, which is historically not true, but that was the story. That was predominantly the case for a lot of these diseases, but it became a broader story. There was a kind of pathologizing of populations, people, places, even though the conference itself did not intend to do that. The story mutated just like our microbes mutate. As the story mutated, that began to be a convention of the story. There was always a kind of easy stigmatizing that happened. Of course, that was exacerbated because whenever there’s a crisis, any “us and them” gets more pronounced.

The story mutated just like our microbes mutate.

I’ll give you an example from the science that I think allowed this to happen and that is the metaphor of microbial warfare. You can say, “Oh well, it’s just a metaphor”—practically every article in these collections uses this metaphor of microbial warfare and also border-crossers. Microbes know no borders, they’re border-crossers and so on. Those two metaphors are characteristic of how something we say incidentally in our speech reveals a lot about how we’re thinking about the problem, even if we don’t know we’re thinking about it that way, and you see that as it gets picked up by mainstream media and popular fiction and film. There’s a battle between the enemy microbe and the heroic researchers and epidemiologists over the fate of humanity. These diseases are always catastrophic. They are species-threatening. There’s an apocalyptic quality to this. There’s this battle that happens and ultimately, in almost every case, it is resolved by epidemiologists and medical scientists and it’s eventually contained after much damage has happened and humanity gets a renewed sense of itself and a second chance. This outbreak narrative takes on, especially in its fictional forms, almost a mythic quality, [starting with] an apocalyptic threat and then a sense of renewal and rejuvenation and new start that comes out of it.

The problem is—in addition to all the potential stigmatizing that happens in the outbreak narrative and these pathologizations—ultimately the story affirms epidemiology and medical science as the only solutions. Animating the microbe and creating it as the enemy undercuts the message the participants in the 1989 conference were trying to convey, which is that human agency is responsible for the problem, and human practices have to change. A war implies an enemy that is causing the problem. Moreover, while scientific medicine and epidemiology is certainly part of the solution, their point is that human beings have to change their practices as well. It is a social, geopolitical, and economic problem as well as a medical one.

Animating the microbe and creating it as the enemy undercuts the message . . . that human agency is responsible for the problem, and human practices have to change.

KW: Yeah, I was going to ask you about some of the consequences of the outbreak narrative. In your book you talk about stigmatizing groups, like you just mentioned, and even the way that it can impact survival rates and the kinds of responses that can even be imagined in the first place.

PW: At a 1978 conference called the Conference of Alma-Ata, a place formerly in the Soviet Union, 134 nations and 67 NGOs [got] together and said they were affirming the UN definition of health as a fundamental human right. The idea was that all of these signatories would commit to this definition of health not as the absence of disease, but as proper nutrition, access to primary healthcare, proper shelter and clothing and basic needs for human wellbeing. All of the signatories committed to work for universal access to primary healthcare by the year 2000.

Addressing global poverty [is important] to preventing outbreaks from becoming pandemics, since poverty—which makes people disproportionately susceptible to disease of all kind, including communicable disease—is the single biggest vector that can turn an outbreak into a pandemic. [But] those stories are not the stories that are being told by the outbreak narrative. [In] the outbreak narrative, [the outbreak] is the beginning of the story—not these other mandates [to regulate development practices, address socioeconomic inequities worldwide, and provide universal healthcare access]. The danger of the outbreak narrative is it does not put the problem of outbreaks of catastrophic communicable disease in this broader context.

KW: I’m wondering if you’ve noticed any of those consequences in our current pandemic moment. Are you seeing the outbreak narrative operate in a similar kind of way this time around? Are we calling back to the SARS epidemic or Ebola or earlier pandemics in our response?

PW: We can see it in our government’s calling it the “China Virus” or the “Wuhan Virus” or the “Kung Flu.” All of that racist terminology [reflects and encourages] an upsurge in anti-Asian racism—people getting beaten up on streets, businesses being boycotted when they were still open. New York’s Chinatown really saw loss of business. This was when other businesses were not seeing that, when [the virus] wasn’t yet in New York or known to be in New York. [You] can see the criticism people have of the wet markets and, “Oh well, those customs over there”—that is an element of the outbreak narrative. And we can see it in the focus on the outbreak itself—which is understandable in the midst of a crisis—but I hope when we tell the story of the COVID-19 pandemic, we will tell it in this broader context and begin to talk about the changes we need to implement to live more responsibly—and more justly—in the world.

KW: And it seems like in more recent incidents of SARS or Ebola, there’s been this threat of a disease but it is emerging from elsewhere and is approaching the United States but hasn’t yet really taken hold. This feels like we’re really playing out some of what the outbreak narrative has imagined for the first time—in at least the memory of most folks who are alive [in the US] right now.

PW: Yeah, the last time was the 1918 flu, so it’s been literally a century. That’s an excellent point. I can’t talk about a coronavirus outbreak narrative yet. I mean, we’re still hearing the language of the carrier and the super-spreaders. That’s another element of the outbreak narrative, [stigmatizing] particular individuals who are seeding the outbreak.

But we can’t talk about an outbreak narrative until it’s over. One of the things about a narrative is it has its end. I will look back at this to see if there’s been any change and what it means when people actually live through it worldwide. If you lived in Hong Kong or Singapore or Toronto or Guangzhou, you lived through SARS. This is not new to everyone. The globality of it is what’s new. It will be interesting to see how the actual experience changes that story and I do feel that there is an increasing effort to tell the broader story, to give that broader analysis that I’m interested in having people think about. I’m hearing more journalists talk about the broader things. One thing that’s gotten added is people talking about the environment and how climate change is one factor in emergent diseases. It’s development practices, it’s climate change, it’s global poverty, it’s lack of access to healthcare. All of these have become things people are paying attention to.

This is not new to everyone. The globality of it is what’s new.

Also, I attended a webinar last night, “Under the Blacklight: The Intersectional Vulnerabilities that COVID Lays Bare, Part 2” [hosted by the University of North Carolina School of Medicine’s Center for Health Equity Research on April 1, 2020], where people were talking about all the invisible people who are exposed, heroically keeping the rest of us alive. We talk about the healthcare workers and I am deeply grateful to the healthcare workers. There’s even talk, I’m glad to see, about how people running stores like grocery stores and pharmacies are also on the frontline. That’s very important. But these people were also talking about farmworkers that most of us are not seeing or talking about who are not being given protective gear who are working in dangerous and unhealthy conditions anyway, but compounded by the virus, without whom we wouldn’t be eating. I’m hearing more and more efforts to pay attention to these broader social justice questions and I’m really gratified to see that.

KW: And if the idea is that the outbreak narrative in its former iterations precludes those kinds of messages, they’re making their way into the conversation now. It could be that that story is already changing in this moment.

PW: Right, and [some of these ideas] were there before. People like Paul Farmer, who [argues that disease hits the poor harder than the nonpoor], have paid attention to social inequalities and how they get lit up by events such as this one. But I am hearing it more and more in mainstream journalism. I hope they are signs that we are ready to tell a new story about this problem.1

KW: These moments of epidemic or pandemic light up some of these things that go unnoticed. It takes me to my next question about how these moments of isolation—or, in this case, social distancing—are making us hyper-aware of how we’ve always been interconnected. As you noted in Contagious, epidemics have the potential to tear apart social order, or maybe they can evoke a profound sense of social interconnection. A phrase that you have used to describe this is “communicability configuring community.” I’m wondering if there are ways that you see COVID-19 configuring community.2

PW: Yeah, in two different senses. Definitely in the social sense, as people are making a real effort to help their neighbors and to be aware of who has particular needs. We were asked to be aware of ourselves as social beings and the need to take care of each other—having groceries delivered and running errands and doing things for people who can’t get out. But also in the sense of being careful of the people who are at more risk. Not going into certain places because you’re going to expose people who are at greater risk from the disease than you may be.

Contagion is the best metaphor for community there is because we need each other and we’re interconnected, and that’s what contagion shows us, it shows us that we’re a community. It shows us our needs for each other, which I think social distancing has made us hyper-aware of. But at the same time contagion can also be contagion of ideas, right? And those ideas can be inclusive or stigmatizing; it can expand community or contract it. It also shows us the ways that other people are also a danger in a variety of ways—that any community has the paradox of being necessary and positive and also dangerous for any individual.

KW: You also talk about this kind of community formation as a way of enforcing national belonging in Contagious. I’m wondering what role the nation plays in the midst of a global pandemic. Are you seeing similar arguments about national belonging in the response to this epidemic?

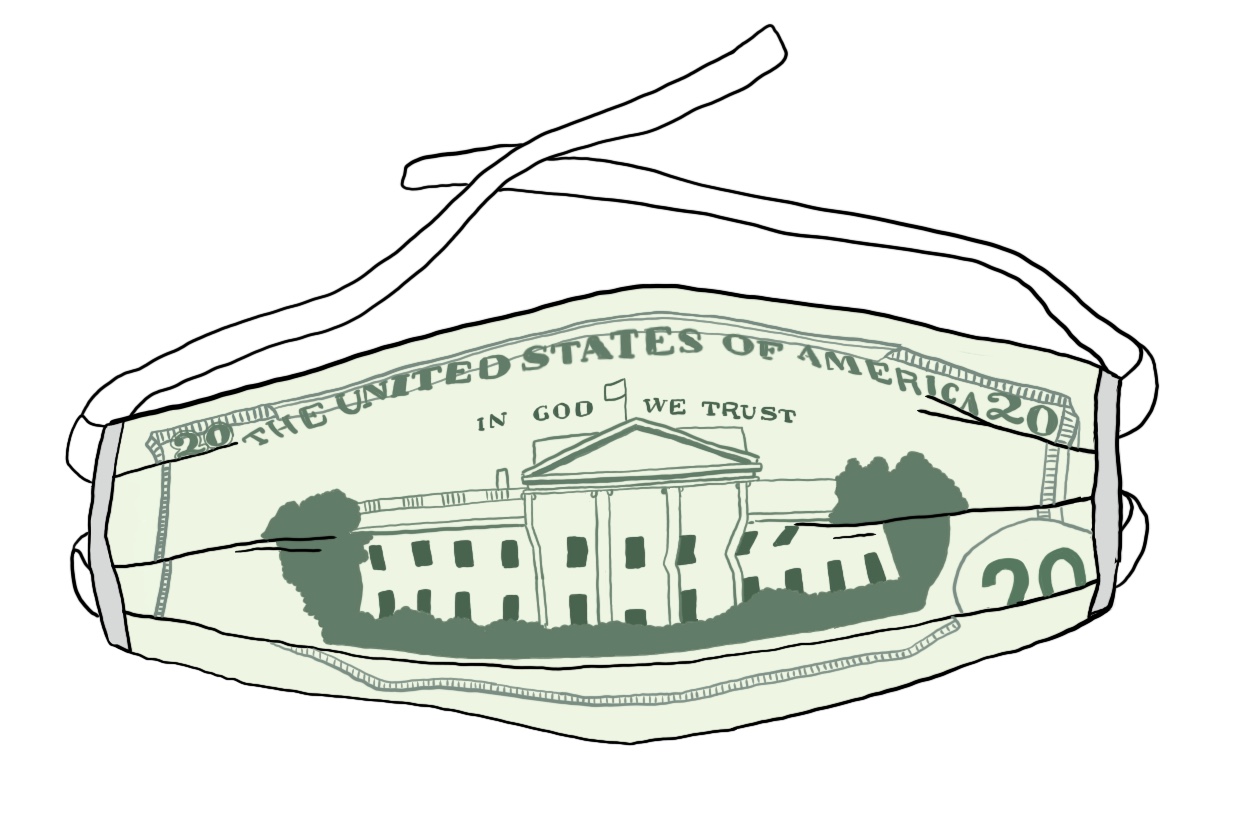

PW: Yes, and so if a disease knows no borders, a nation has a responsibility for the health of its population. That nation tries to reinforce the borders that the disease is trying to cross. That’s where the anti-immigrant metaphor of the illicit border-crosser really comes out. Nonetheless, quarantines are really important, whether they’re local or national or whatever. A nation does have that responsibility to try to protect its population. That’s the function of the nation. During a pandemic, on the one hand we see the globalization; on the other hand there’s a resurgence of the importance of the nation as the thing that’s going to protect people, that’s going to enforce a quarantine, that’s going to get the development of the vaccine going and the pharmaceuticals and it’s going to fund these things. All of that is a national responsibility and reminds us that we are in a nation.

[But] the other thing that happens, as I said before, is the us/them. Nationalism is all about an us/them. Every us/them gets exacerbated during a crisis of any kind and especially one like this. The [antagonism toward] other nations, [the language of] the “Chinese virus,” the “close this border,” the “militarize the Canadian border,” all of that gets pronounced. Even though militarizing the Canadian border made no sense at all. There was also talk early on of protecting the Mexican border even though [the virus] was in the US. Mexico should have been protecting the border, not the US. Again, it shows us how the political picks up on the medical.

KW: Then who counts as belonging to the nation? Who is protected or supported by, say, the stimulus package? There are so many holes for folks who haven’t filed taxes in recent years or undocumented immigrants living within the United States who aren’t considered citizens.

PW: Absolutely right. There’s a term historian Alan Kraut coined, “medicalized nativism.” Medicalized nativism is the use of medical threat to make nativism palatable or to enhance the arguments of nativism: “They are bringing in diseases. They’re a threat to the population. We owe it to the population to keep them out.” This goes back to the turn of the century to the stuff that I was interested in in my first book and how I came across Typhoid Mary.3

KW: So far, we’ve been talking about national responses to epidemic disease—in the form of medical nativism and border protection—but I’m wondering how this plays out on a regional level. Does the outbreak narrative lead us to believe that we need to close not only our nation’s borders but also close off towns from surrounding areas? Are there impacts of inconsistent regional responses to COVID-19 that inspire the same kind of xenophobic thinking as medical nativism? Or can a strengthened sense of regional belonging also be a positive thing, fomenting a sense of shared experience and mutual accountability?

PW: There’s a refrain that runs through a lot of the global health literature: “microbes know no borders.” That’s part of the double message that contagion carries: that we’re all connected, all interdependent, and that we are threats to one another. That’s how contagion paradoxically reinforces a sense of unity and an exacerbation of “us/them” thinking. From a public health standpoint, it certainly makes sense in the midst of an outbreak to establish a containment zone. Depending on who’s in the zone and who is surrounding it, that can certainly feed into xenophobic thinking. If regions are distinctive racially, ethnically, culturally, it is more likely to exacerbate stigmas and blame. In the case of COVID-19, we are also seeing how politics can affect public health decisions in really dangerous ways, with blame being cast on local politicians and public health officials who are trying to protect the health of their constituents. Since microbes don’t conform to town, city, or regional borders, it can become increasingly difficult to protect a population if responses aren’t coordinated.

The problem with “us/them” thinking is that having a “them” characteristically strengthens an “us.” The fellow feeling that comes from the “us” is important to human beings, but if we depend on having a “them,” we reinforce the stigma and bias. The slogan “we’re all in this together” that has emerged is an effort to form an “us” that includes humanity. I think that’s part of the unconscious—or maybe conscious—rationale of demonizing the virus. As I’ve said, that has its dangers too—we don’t want to create a viral enemy that allows us not to see how we humans have created the conditions for disease emergence and to think about how we have to change our way of being in the world collectively. But the more inclusive our thinking is, the more we can work together productively to do so. And let’s not forget, we also have plenty of examples from history in which crises of all kinds brought out the best in people, heightening fellow feeling and eliciting a communal response. The more each of us can imagine what it would feel like to live in others’ lives, the better, I think. And the more inclusively we can all think, the more we can collectively begin to work for a world that is more just, more equitable, and in every sense healthier for all. If this crisis gets us thinking in those terms, perhaps we can salvage something worthwhile out of this calamity.

There’s a refrain that runs through a lot of the global health literature: “microbes know no borders.” That’s part of the double message that contagion carries: that we’re all connected, all interdependent, and that we are threats to one another.

KW: Your book covers public health responses to epidemic disease from Typhoid Mary in 1906, through most of the twentieth century with the emergence of HIV. I’m wondering if, with this longish history of public health responses in mind, there are past moments of outbreak that we can learn from or borrow from in our current moment?

PW: You mean in positive ways?

KW: Yes, well, I guess can we learn from mistakes or are there tools or ideas that we should be bringing into our current response?

PW: I’ll tell you a very important mistake to learn from that is, again, evidence of how strong a narrative can be. In the HIV pandemic, in the early years, it was called gay-related immune deficiency, or GRID. There was such a strong sense—that the name carried in the narratives—that it was a disease of gay men that it made people look in some wrong directions for the cause and not pay attention to modes of transmission they could have been aware of sooner, particularly the blood supply. That this was carried by blood and was in the blood supply. The number of hemophiliacs who were getting this disease should have been a clue, but nobody was looking at them because they were exclusively—in the US—convinced it was a “gay-related immune deficiency.”

KW: Right, because that’s a big part of the outbreak narrative is the crime drama, the search for the source.

PW: I mean, in [the case of COVID-19], we identified the disease and transmission pretty quickly so this isn’t so relevant here. SARS even took longer than this one did. Now, with genetics, we can type the genome and learn lots about a disease pretty quickly. This differed from HIV. Nonetheless, [our narratives can lead us to think in misguided ways] about roots of transmission.

One thing we can learn from both the 2014 Ebola outbreak and this one is, on the one hand, the outbreak narrative is the narrative about fear and panic and so on, but it’s also a narrative of reassurance. Even though the outbreak narrative is about the threat of pandemic and the escape from the initial outbreak, [the virus] getting out into some aspect of the population, there’s also a sense that, because it’s happened many times, it’s containable. That we can contain this. I think we should learn that when any of these things happen we shouldn’t wait until we see it get out into the population. We should be paying a lot of attention a lot sooner to the importance of containing it. I think that was true in this case and it was true in the case of Ebola that it was allowed to get out more quickly because there was a sense of, “Oh well, we’ll contain it.”

The outbreak narrative is the narrative about fear and panic and so on, but it’s also a narrative of reassurance.

When they were screening passengers coming in from China in the US, a friend of mine had been in China, her flight got canceled, and she got routed through Japan to Detroit to the Washington, DC, area. She was not sick, as it turned out. But nobody screened her. She just walked off her flight. She happens to be a doctor and she was in China when the outbreak happened. She lives in the US. It terrified her. This happened when [the virus] was already in China and she said, “This is going to be a disaster.” She said it then. She didn’t get screened, even though she was indirectly flying in from China. For all of our government’s desire to close borders, they did not screen our flights sufficiently.

KW: I’d like to close things out by returning to this idea of narratives having consequences. Are there certain narratives that we should be rejecting at this stage? If so, what are some of the stories we should be telling instead? How do we go about changing the story that we’re telling about our current moment?

PW: Well, obviously the stigmatizing. People are being critical of it. There is a lot of pushback about that, which is good, including journalists pushing back against the president. I guess I would say that, in a positive sense, I hope a lesson that comes out of this is to move us towards changing the story in the way that I began this interview. The Alma-Ata declaration seems to many like something that is so impossible. It’s too big. Yet, at its thirty-year anniversary [in 2008], Margaret Chan [then-director of the World Health Organization] made the theme of the year of the World Health Organization a return to Alma-Ata and asked why are we not doing this. It is within our reach, and it’s not only within our reach but it’s pragmatic.

The World Bank has talked about the infrastructural changes that we need for preparedness, including increasing access to healthcare—even universal access to healthcare is going to cost less than the kind of pandemic that we’re in now or one that could be even worse. The cost, first and foremost in human lives, is reason enough to address these goals, to really take them seriously and make those infrastructural changes, but also the financial cost. For people to say, “Well, it’s impractical, we don’t have that kind of budget”—well, do you have the kind of budget to deal with a crisis like this? The things we could do that would contain these outbreaks much more effectively [would include] universal access to healthcare and addressing global poverty aggressively the way the United Nations Millennium Development Goals has set up. It’s something we can’t afford not to do.4

Kym Weed is a teaching assistant professor and co-director of the HHIVE Lab in the Department of English & Comparative Literature at UNC–Chapel Hill. Her current book project, “Our Microbes: Imagining Human Interdependence with Bacteria in American Literature, Science, and Culture, 1880–1930,” examines the diverse representations of microorganisms at the turn of the century.

Priscilla Wald is R. Florence Brinkley Professor of English and professor of gender, sexuality, and feminist studies at Duke University. She is the author of Contagious: Cultures, Carriers, and the Outbreak Narrative (Duke UP, 2008) and Constituting Americans: Cultural Anxiety and Narrative Form (Duke UP, 1995) and is currently at work on a book entitled Human Being After Genocide.NOTES

- Paul Farmer, Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 140.

- Priscilla Wald, Contagious: Cultures, Carriers, and the Outbreak Narrative (Duke University Press, 2008), 12.

- Alan Kraut, Silent Travelers: Germs, Genes, and the Immigrant Menace (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994), 3.

- “Millenium Development Goals (MDGs),” World Health Organization, accessed April 22, 2020, https://www.who.int/topics/millennium_development_goals/about/en/.

FURTHER READING

Public health history and analysis:

Neel Ahuja, Bioinsecurities: Disease Interventions, Empire, and the Government of Species

Paul Farmer, Infections and Inequalities: The Modern Plagues

Paul Farmer, Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor

Alan Kraut, Silent Travelers: Germs, Genes, and the Immigrant Menace

Nancy Tomes, The Gospel of Germs: Men, Women, and the Microbe in American Life

Judith Walzer Leavitt, Typhoid Mary: Captive to the Public’s Health

POPULAR MEDIA FEATURING THE “OUTBREAK NARRATIVE”

Books:

Contagion, by Robin Cook

The Coming Plague: Newly Emerging Diseases in a World out of Balance, by Laurie Garrett

The Blood Artists, by Chuck Hogan

Carriers, by Patrick Lynch

The Hot Zone: The Terrifying True Story of the Origins of the Ebola Virus, by Richard Preston

Film and television:

Outbreak, film directed by Wolfgang Petersen

The Stand, miniseries directed by Mick Garris

Contagion, film directed by Steven Soderbergh

The Hot Zone, miniseries created by James V. Hart