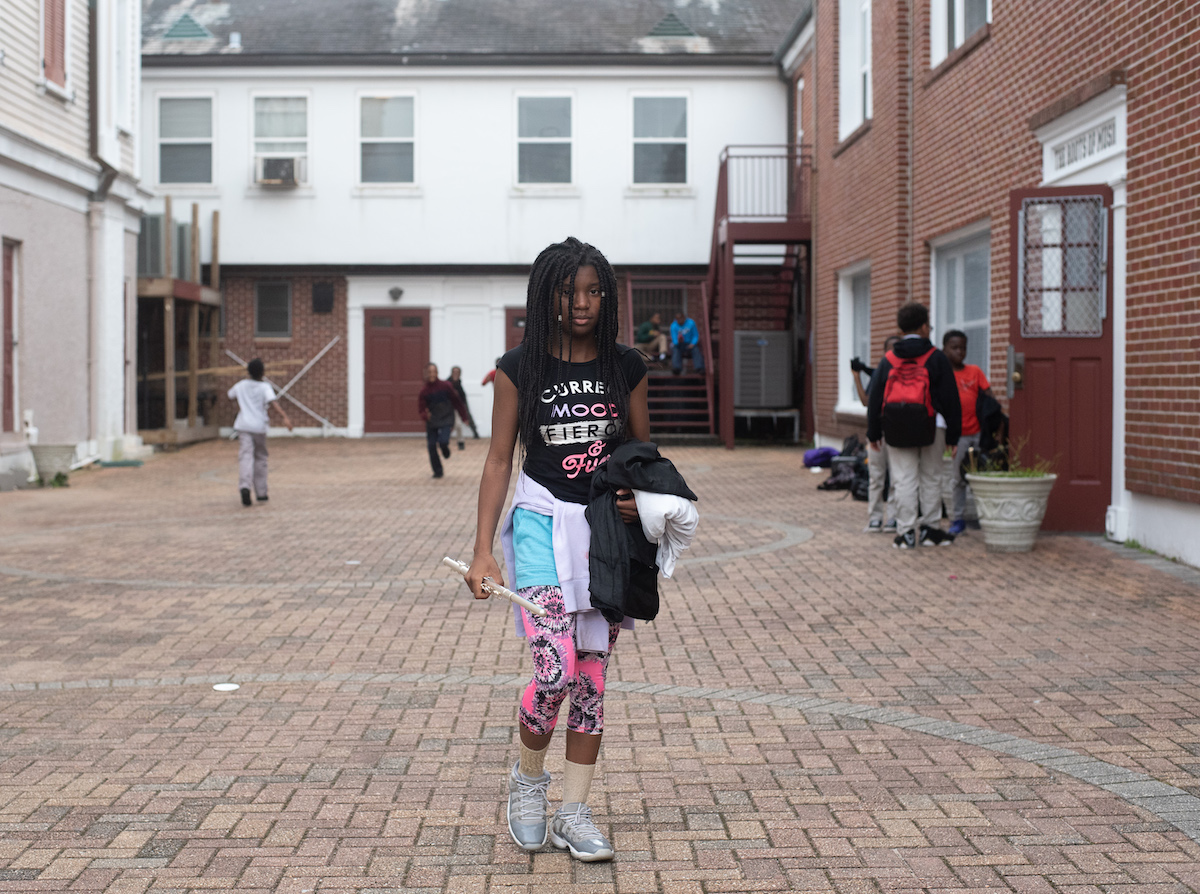

Summer is the season when the new recruits arrive. They are kids, eight or nine years old, and most have never touched an instrument. On June 20, 2019, I crowd into an air-conditioned classroom with about thirty of them, sitting on industrial carpet, facing forward. LeBron Joseph stands in front of the whiteboard writing out the notes of rhythm exercises.1

“Band, we ready?”

“We always ready!”

LeBron counts off, “One, two, three, four. One, two, ready, and . . .”

The kids chant the note names while clapping, “Half-note, two, half-note, two. Whole-note, two, three, four . . .”

“Stop,” LeBron interrupts. “Hey, my man,” he waves the marker toward the back. “Get out. Both of y’all.” The room gets quiet and everyone turns toward two boys. “Neither one of y’all are clapping or humming rhythm. And you talking.” One gets up and heads for the door while the other fumbles with his binder and backpack. “Hey, hey, hey,” LeBron commands without raising his voice. “Stop what you’re doing, drop everything, and just get out.” The second child rises quickly. “Let me catch you not clapping and singing along,” LeBron warns as the door shuts behind them. He scans the room, tapping the board in tempo.

“One, two, three, four. One, two, ready, and . . .”

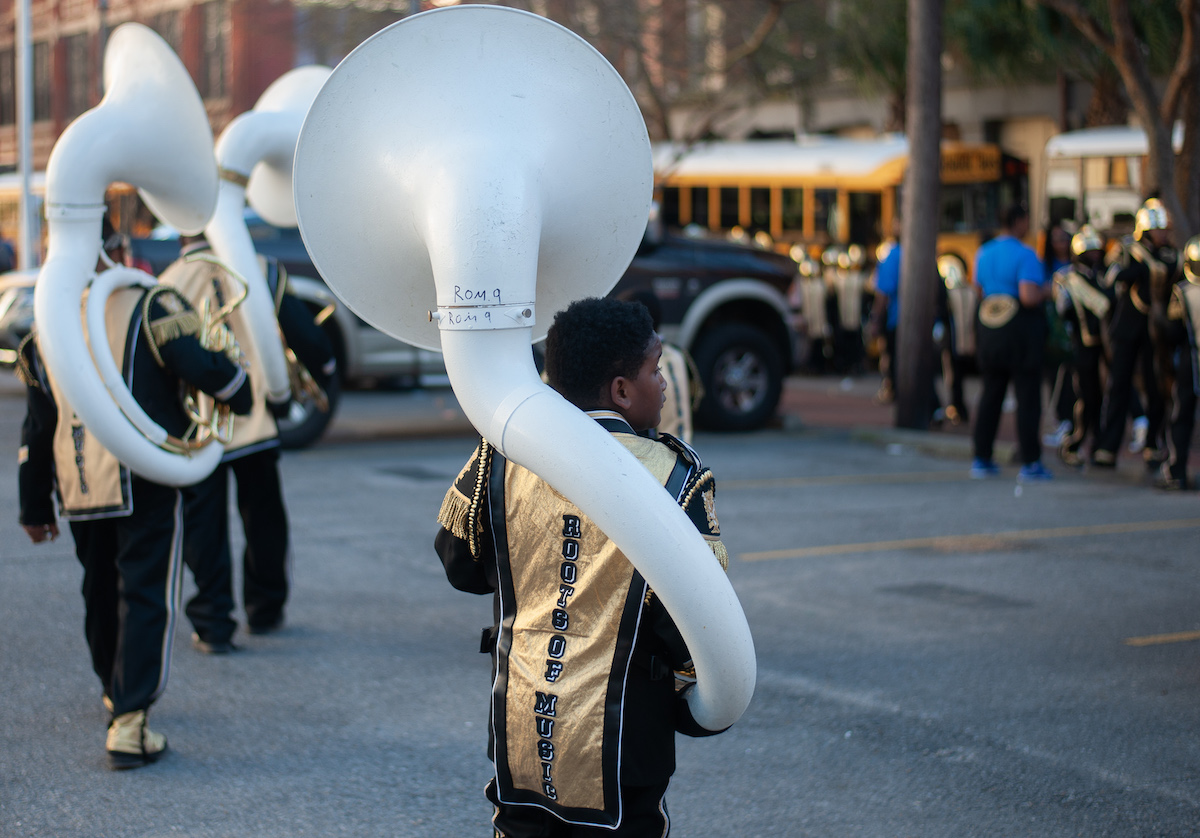

LeBron is a teacher at The Roots of Music, an after-school program in New Orleans. Back in 2008, when I first met LeBron, he was twelve years old and just starting out on trombone at Roots. Hurricane Katrina had wiped out the city, so the state legislature took the opportunity to wipe out the public school system, turning it into a “non-system” of mostly independent charter schools. In the upheaval that followed there were hardly any middle schools offering music. Drummer Derrick Tabb of the Rebirth Brass Band set his mind on founding a program to teach kids how to play in a marching band, offering them free academic tutoring, meals, and transportation, five days a week, year-round. He asked me for help with the relentless hustle to get teachers paid, cover expenses for busing and meals, and have instruments donated. Now, Roots has a full staff and its own facility, but Derrick’s teachings remain the same as when he taught LeBron and others that first year. Kids start out with the basics: positioning their fingers on the trumpet valves and tapping out rudiments on rubber drum pads. By the winter, they’re playing full songs and running practice drills, gearing up for the Mardi Gras parade season, when they’ll march down the wide boulevards in matching black and gold uniforms, perfectly in step, with horns up, wowing the crowds pressed against the police barricades.

It takes discipline to play and march for six or seven miles. Discipline is what defines the entire “show-style” tradition of Black southern marching bands that the Roots kids are initiated into. Just like in sports, learning teamwork in band is all bound up with learning competition. Members compete against each other to get first chair, to be made section leader, and to be crowned drum major. Sections compete against other sections and bands compete against other bands. When bands line up against each other in the stands at football games, or perform their field shows at halftime, they are there for battle, and there will be winners and losers. Egos get bruised. Sometimes kids come to blows. Every band director reigns over a military-style hierarchy, meting out punishments and rewards. Discipline is what LeBron introduces in the rudiments class for the new recruits, and discipline is what band director Darren Rodgers enforces at every rehearsal and performance.

At an evening rehearsal in January 2020, three weeks before Mardi Gras starts, Darren is preparing for a practice parade through the French Quarter. It’s chilly and dark and everyone has on a matching black hoodie with a gold Roots of Music logo on the front. For warmup, they gather in a semicircle, concert-style, with Darren and the three drum majors up front. Darren signals the drummers in the back to start their cadence, then the wind instruments enter with four blasts of the whistle. They’re playing his arrangement of “The Whole World” by Outkast. The original has all the elements necessary for transposition to band: a heavy, syncopated beat for the drum section, a hummable bass line for the sousaphones, a melodic hook with layered harmonies that Darren has spread across the trumpets and baritones, and a countermelody assigned to the woodwinds and trombones. Altogether, it is perhaps the most enormous sound a hundred or so adolescents can make with acoustic instruments. But Darren is unsatisfied.

“You can put a little oomph on some of the notes.” He paces in his black- and-white checkered Vans, grey joggers, and black Saints hoodie, singing the countermelody: BAH bah-da, BAH BAH bah-da-da.

“Y’all sound like a third act. Y’all sound like the Kidz Bop version. I need you to come with that smoke.”

The drum major blows the whistle and the band counts off one-two-three-four-five-six-seven-eight and starts blasting again. We’re assembled in a narrow quad between two tall buildings and the force of the sound bouncing off the bricks feels like it’s going to sear my head off. But there’s still not enough oomph for Darren and he signals them to stop with a flick of his wrist.

“You sound like little babies when you sound off. So I know that first note’s going to be weak.” He turns toward the woodwinds and trombones: “I told you you’re too nice. Put some aggression on the notes. Sound mad or I’ll make you mad. OK?” Darren is passing on what he learned at St. Augustine High School, Southern University, and Talladega College: bands that sound weak can’t compete with the headliners. After a successful run through, everyone lines up and files out the gate for a practice run to build up stamina.

The brash sound and the fierce presentation that Darren is striving for—that all Black southern marching bands strive for in their different ways—has everything to do with gender and with race. The US was built upon the exclusion of women and people of color from institutional power, and their incorporation into existing hierarchies was dependent upon maintaining white male dominance. The regime that bell hooks has termed “white supremacist, capitalist patriarchy” is inherently competitive, and it rewards discipline and respectability, might and militarism. In his book New Black Man, Mark Anthony Neal puts forth an archetype of the “Strong Black Man” who embodies strength, pride, stability, independence, and self-sufficiency and counteracts negative stereotypes of Black men as undisciplined, defiant, and deficient. But Neal and others in Black masculinity studies have argued that the valorization of the Strong Black Man also perpetuates sexism, antifeminism, and homophobia adopted from dominant cultural norms. In an introduction to the special issue “Black Masculinities and the Matter of Vulnerability” for the journal The Black Scholar, Darius Bost writes, “I understand Black masculinity to be many things,” including “a racialized fantasy that overdetermines Black subjects from without” and “a disciplinary mechanism used to police self and other, often manifested through a particular set of cultural norms from which one cannot widely deviate.”2

Marching band is an institution through which norms of race and gender are perpetuated. This is borne out in the life experiences of LeBron, Darren, and other Black men and boys who are the focus of this essay, but that doesn’t preclude discussion of how women and girls navigate the gender hierarchies and ideologies of masculinity that govern band. Everyone is different, but in each case the masculine ideals of toughness, discipline, and competition are entwined with vulnerability, loss, and love. One of Bost’s coauthors, La Marr Jurelle Bruce, writes, “Despite this double bind of pathology and normativity, masculinity still has tremendous significance to the lived experiences of the Black men, women, and transmasculine persons who use it as a mode of self-fashioning, pleasure, belonging, and regulation, especially in light of their vulnerability to trauma and violence.” Toughness and vulnerability aren’t neutral categories but racialized markers of masculinity that have defined the band tradition at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) since the 1950s.3

“You have classical musicians or, like, jazz musicians,” LeBron explains, “You don’t need that type of mental state to do those things. But when you’re built up in this marching band, you want to be monstrous.” He’s describing a look, a sound, a sensibility.

“We’re not just shooting the breeze,” he continues. “There’s certain ways you have to act. You have to get out there in the sun and do push-ups. You have to scream at the top of your lungs.” LeBron, his students, and everyone in band are taught to perform strength while recognizing that their shared vulnerability is the basis for community belonging.

“It’s all a part of the culture,” he says. “But it’s all out of love because everyone wants to be the best.”

Since 2008, I’ve served on the board of directors, helped fundraise, and provided The Roots of Music with volunteers from Tulane University, where I teach. I’ve met hundreds of students who arrived as boys and girls and are now men and women. But I’ll always be an alien in the world of band. I went to high school in Worcester, Massachusetts, in the 1980s, and my classmates were Irish, Italian, Puerto Rican, Vietnamese, Armenian, Jewish, Black, and fellow Syrians like myself. We sang classical music in chorus concerts and the band played old-school marches at football games. When I moved to New Orleans in 1997, I went to my first Mardi Gras parade and heard the St. Augustine High School band play with a level of power, precision, and swagger that shook me off the cultural foundation I’d learned in school.

“I can say marching band, for sure, is one of the hardest cultures for a person outside to grasp,” says LeBron. I cannot know what it’s like to be a part of this culture, or to navigate the conditions imposed upon Black boys and girls, educated in “apartheid schools” that are over 95 percent Black, like 95 percent of the children at Roots. All I can ask LeBron, Darren, Derrick, and others is to show me a part of what’s underneath the monstrous sound and presentation of a 150-piece band, eyes forward, still as statues, in formation, at the ready.4

On Saturday afternoons in the fall, football fans around the country root for Southeastern Conference teams like Alabama’s Crimson Tide, the LSU Tigers, and the Georgia Bulldogs. HBCU teams are segregated into a separate division and their games have a whole other set of priorities. I can’t say that music takes precedence over sport, but nothing excites the crowd more than band. The seats empty out during the second quarter so fans can get their concessions and be back by halftime for the field show. The “battle of the bands” at every school’s homecoming game is the apex of the season: FAMU vs. Bethune-Cookman at the Florida Classic, Jackson State vs. Tennessee State at the Southern Heritage Classic, or Southern vs. Grambling at the Bayou Classic in New Orleans. For Regina N. Bradley, proud graduate of Albany State in Georgia, “How your band performs was a reflection of how dope your school was. Or was not.”5

When Beyoncé became the first Black woman to headline the Coachella Festival in 2018, she assembled over 350 musicians and dancers into a kind of HBCU variety show, filmed for the Netflix documentary Homecoming. The Houston native says she wanted the movie “to feel the way I felt when I went to battle of the bands and that being the highlight of my year.” Homecoming, though, was innovative in that Beyonce included women in every facet of the performance, creating a vision of a mixed-gender ensemble that in reality is overwhelmingly male. Arising out of the military, school marching bands were not required to admit women and girls until the Title IX antidiscrimination statute of 1972. Women and girls remain largely confined to the majorettes and dance teams while men and boys dominate the band, particularly in percussion and lower brass sections, with some integration in upper brass and more in the woodwinds. There are always exceptions, which is why Beyonce was able to recruit women on every instrument. But the force of her “girl boss” feminism—the swagging, the slaying, the getting in formation—comes partly from inverting images of fierceness and fraternity traditionally associated with men.6

It was William Patrick Foster who turned band into an emphatically Black and unmistakably southern ensemble while retaining its associations with masculinity. As band director of Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (FAMU) from 1946 to 1998, Foster established an HBCU style distinct from that of Predominantly White Institutions (PWIs). He wrote and commissioned arrangements of Black popular music, performed with more strident tones and rhythmic syncopation and emphasizing creative and improvisatory uses of sound and the body. “When FAMU’s 235 pacesetters step on the field, anything can happen,” writes dance historian Jacqui Malone: “barrel turns, backbends, hitch kicks, swivel turns, pelvic thrusts, pelvic rotations—they glide, they slide, they slither and skitter.” At the same time, Foster retained the uniformity of sound and presentation from military and corps-style college bands. In his book Band Pageantry, he insisted that “formal discipline is necessary for the perfection of techniques” so each member is “alert, poised, and ready to execute any movement on the instant.” The result is an in-your-face respectability; a defiant, steely-eyed call to battle and a liberating dance of joy. Foster became the first Black American to serve as president of the College Band Directors National Association and his techniques were heavily appropriated by corps-style bands at PWIs. It is no coincidence that it was this man—nicknamed “The Law” and always seen conducting in a military suit and cap—who broke racial barriers over a career that spanned the civil rights era and the period Bradley calls “the rise of the hip-hop South.”7

Today, FAMU is one of forty or so HBCU bands in the Southeast. Throughout the “marching band belt” that stretches from Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas over to Texas, high schools emulate the college bands and serve as feeder schools for the most talented graduates. In New Orleans, school marching bands are an integral feature of the Mardi Gras season and are also part of a cluster of local parading traditions, including Mardi Gras Indian ceremonies, jazz funeral processions, and second line parades. As a child in the 1980s, drummer Derrick Tabb grew up performing in funerals and parades and eventually joined the renowned Rebirth Brass Band, which was honored with a Grammy Award for “Best Regional Roots Album” in 2012. Derrick is widely considered the best snare drummer in New Orleans and he credits his middle school band director, Donald Richardson Jr., for grounding him in the techniques. Drummers learn by short patterns called rudiments—double strokes, paradiddles, flams, rolls—and Richardson ensured they were memorized by calling on students to audition them in front of the whole band. At the critical juncture that is adolescence, he demanded discipline in their musicianship, their posture and movements, and their behaviors.

Derrick was always the tallest kid in class and always getting mixed up in fights. His grandmother had kept him in check but Derrick went into a tailspin after she died and “started hanging out with the wrong cats.” When he got in trouble at school, the principal would send him to the band room for detention, and Richardson might make him clean up the entire football field by himself. “He could tame me as long as his eyes was on me. But I was rebellious.” Derrick got himself expelled from Bell Junior High and partied all through high school and after. But he kept disciplined on the drum, developing a virtuosic style that landed him in Rebirth in 1995. As a touring musician and a father, Derrick gradually came to appreciate the discipline Richardson had impressed upon him. After Katrina, he set his mind on starting a band patterned after Bell, and, like Richardson and Foster, he has presided over his dominion with total authority.

The day the roots of music opened, May 22, 2008, forty-two kids walked off a yellow school bus and into Tipitina’s nightclub for rehearsal. One was LeBron Joseph, twelve years old, just back from Baton Rouge where he’d evacuated with his mother and grandmother. We talked a few times after LeBron started the Street Runners Brass Band with my neighbors, Reginald and Jaron Williams, who had also joined Roots. A brass band is smaller than a marching band, designed for improvising, and when the Street Runners rehearsed in my yard, I could tell LeBron had experience. His older cousin Ellis led the Free Agents Brass Band and would take him along to shows. “I was actually able to see hands-on what happens at the gig, what happens after the gig, what happens on the way to the gig,” LeBron remembers. “Like, all the stuff that I’m supposed to see and the things I’m not supposed to see, I was able to see it at a very, very young age.”

When he wasn’t at rehearsal, or school, or tagging along with the Free Agents, LeBron would meet up with friends from his Eighth Ward neighborhood. “I was hanging with guys in the streets. Guys who were selling drugs. Guys that were robbing people.” One evening, police stopped them and put one of his friends in jail. Another night somebody got shot. LeBron was at Roots and didn’t hear about it until after. “I’m like, ‘Man, the only thing that’s saving me from being a part of any of this stuff right here is me going to band practice.’” He found a community of kids with shared experiences. “They have some of the most gangster people in the band room, and they still have these same levels of intensity that they can get to, you know?” His voice rises in pitch and volume and his body language becomes more animated at the memory. “They will still be ready to knock your head off, but they’re just like, ‘I’m going to do it with my instrument.’” In my mind I can see LeBron at twelve, but the person facing me now is a grown man; still jovial, silly even, but never soft. Much of that transformation was shaped in the band room.

The Joseph family sends their boys to St. Augustine, the only all-Black, all-boys Catholic high school in the US. The school was founded in 1951 by Josephite priests and brothers with a mission to provide a “training ground for leadership through academic excellence, moral values, Christian responsibility and reasonable, consistent discipline.” In the civil rights era, the figure of the “St. Aug man” became a fixture on the front lines of desegregation. Graduates include the city’s first two Black mayors—Ernest “Dutch” Morial (1978–1986) and Sidney Barthelemy (1986-1994)—and numerous other politicians, doctors, lawyers, businessmen, military officers, and professional football players. The school advances a politics of respectability tailored specifically for Black boys to excel in a structure of white dominance. “The Purple Knight is a symbol of manly virtue,” wrote Father Eugene McManus, a teacher and principal. “He holds honor high [and] will never permit anyone, including himself, to disgrace it.”8

Taking their name from FAMU, the St. Augustine Marching 100 became the school’s ambassadors under the leadership of Edwin Hampton from 1952 to 2006. “Hamp” was a military veteran and a graduate of Xavier University, the only Catholic HBCU, where he studied classical music. “I tried to combine these two elements,” he explained before his retirement. “The music we tried to play with the same attention which we would have in playing a major symphony, and since we had all boys, I thought we could take the route of military discipline and military movement and maneuvers.” In 1967, after St. Aug won a state lawsuit to gain admission into the all-white Louisiana High School Athletic Association, the band’s meticulous halftime shows, with perfectly aligned rows of bended knees, were unveiled to white opponents. That same year, St. Aug became the first Black band to participate in the Krewe of Rex parade on Mardi Gras day, alongside dozens of white bands. Marching through the tightly packed French Quarter, spectators spat, threw bottles, and poured urine from balconies down onto the band. Hamp had instructed the boys to look straight ahead, without reaction, and that’s just what they did. On the frontlines of struggle against white supremacy—not only in politics but also sport, music, and even Mardi Gras—St. Aug men mounted an offensive of Black excellence.9

Show-style bands came to rule the streets during Mardi Gras and many have battled St. Aug—Landry-Walker, Edna Karr, Warren Easton are strong today—but the Marching 100 has kept the title “Best Band in the Land.” When Pope John Paul II arrived at the New Orleans airport in 1987, the archdiocese sent St. Aug to greet him. They have performed for eight US presidents and at five Super Bowls. In the wake of Title IX legislation, as girls have filled the ranks of band, it is telling that the only all-boys, all-Black band in the city remains the standard-bearer. The St. Aug man is the epitome of the Strong Black Man, a model of bodily control and behavioral discipline, combining respectability with showmanship.

By the time LeBron enrolled in 2009, St. Aug was under the direction of Virgil Tiller, who had served as drum major under Hamp in the class of ’95. LeBron, too, rose through the ranks, becoming section leader of the trombones and then drum major. The drum major is the drill master, the student leader, the peer disciplinarian. He is always out front, long mace in his right hand, ACME Thunderer whistle on a lanyard around his neck, and feathered shako high on his head. In the balance between teamwork and leadership that is characteristic of any ensemble, the drum major embodies the jockeying for position necessary to rise above. “The drum major,” Foster wrote in Band Pageantry, “should be dignified in his conduct, smart and graceful in his movements”; ideally, a “tall student of striking physique” whose measure of success is “his appearance and efficiency in drill of the organization.” LeBron is not particularly tall, but the determination to overcome perceived shortcomings might be the ultimate leadership quality in an institutional culture that values resiliency and unflinching loyalty. A hierarchical cooperative, it is understood to be a company of men, a band of brothers, or simply “the brotherhood.”10

Darren Rodgers was two years ahead of LeBron at St. Aug and after graduation both went on to Southern University. Though Southern’s campus is ninety miles away in Baton Rouge, there is no college that looms larger in the social lives and collective imaginations of Black New Orleanians. The Human Jukebox is Black excellence personified, attracting the best students from high schools across the region to audition for coveted scholarships and then compete for leadership positions. When Darren was appointed first baritone as a freshman, he became a target for older students. “The upperclassmen came. Of course. That was ridiculous, you know?” Darren explains how the director assembles a hierarchy during summer band camp, when seniority can be upended by talented youngsters. “The upperclassmen, they’re not really friendly at all. They’re really trained to not talk to you, not deal with you.” Slight in stature, Darren learned from his father—an Army vet who has worked at the Port of New Orleans for over thirty years—to be “strong and militant,” with “zero tolerance.” His upbringing helped him hone a “first chair mentality” over the course of the season. “Me being the person that I am, I wasn’t nice at the time. If I felt this dude had an attitude or treated me wrong, I did the same if not worse to him.” During the football season, the lifeblood of the fall semester, this internal dynamic of competition is directed outward, toward an opponent, at every game.

Twenty-two years after moving to Louisiana, I attended my first Southern football game on November 16, 2019. Early that morning I picked up three friends and drove a couple hours north to Jackson, Mississippi, for the BoomBox Classic. The name is a mash-up of the two most renowned bands in the Southwestern Athletic Conference: Jackson State’s Sonic Boom and Southern’s Human Jukebox. The first thing you hear is the drums of the Sonic Boom in the distance and the first thing you see is the drum majors and J-Settes dancers leading a column of musicians down the length of the field, through the end zone, and up into the stands. When Southern makes their entrance, J-State welcomes them by playing a warmup song, as if they can’t be bothered to listen to their opponents’ cadence. From the outset the rivalry is as much musical as athletic.11

This pregame showdown is called the zero quarter, when each band gets in position, diametrically across the field, and starts blowing at one another. My friends all grew up in band and we sit in the end zone between the two sides so we can compare notes. “J-state is what we call ‘country,’” says Jaron, who started out the year Roots opened and went on to lead the trumpet section at Southern. “It gives you more of a rock side-to-side type of feel.” The drums and sousaphone take precedence, laying down beats straight out of Dirty South hip-hop, sending the drum majors and J-Settes into motion. At Southern, Jaron tells me, “We have more of a finesse-type. We’re more controlled and have more moving parts in our music.” Southern’s sound is blistering yet flawless, invincible, like a trumpet frontline leading ground operations while the other sections fly over dropping bombs.

“Everybody wants to just murder Southern,” says Aysja Mallery, a graduate of Roots and the current assistant section leader of Southern’s mellophone section. “You have to go there and have the right mindset to blow them off the map. You want to bust the field show. You want to play the fifth quarter and still blow their face off. And just leave and say you have that victory.”

Anytime a team scores, its band launches into a victory march and the fans wave pom-poms to the beat. The music never really stops; the bands are always trading songs or playing simultaneously in a glorious sound-clash that maintains a steady hum of excitement. At halftime, Southern’s show includes a drill where the members spell out the score—Tigers 24, Jaguars 17—by lining up in the shape of each number. The Sonic Boom exploits their home field advantage, finishing their show by mimicking one of Southern’s well-known drills to gleeful cheers. J-State’s announcer taunts the visitors: “How about you go eat you some Wheaties and try again next year?” Our Louisiana crew is biased and by the time the game ends we’re openly cheering for Southern despite the looks from J-State fans. We stay for the fifth quarter, when the bands play their most popular arrangements, and then file out as members of each side congratulate themselves.

When I met with Aysja and Derrick at The Roots of Music facility, she told us that playing for Southern is a dream come true. She’d been at Roots from the very beginning and then gone on to become section leader at Landry-Walker High School and the first female assistant section leader in Southern’s history. And she did so on the mellophone, part of the lower brass family of instruments that are perceived to be the domain of men. Aysja had initially been assigned the clarinet at Roots, but she resisted, telling the teachers, “I don’t want to play this no more. I don’t feel comfortable with this. This isn’t me.” Derrick watched her overtake the mellophone section in a matter of months. “The determination, the focus, is there. You can just see it, you know?” She raised the level of performance for the whole section. “Now, you’ve got boys who don’t want the girls to be the best,” remembers Derrick, “but she’s steady pushing past them.” Band is a man’s world, and for a girl or woman to excel, Aysja says, “You have to have the right mindset.” That means thinking “positive thoughts,” having a “support system,” and being “on guard for whatever comes your way.”

When Southern performs, there is no jewelry, makeup, or visible piercings allowed. The uniforms, helmets, gloves, boots, spats, and even hairstyles must all match. “The girls, we all team up and we’ll do each other’s hair,” says Aysja. “We’ll put it in two braids or we’ll put it in a bun in the back but that’s the only two styles we’re allowed to have.” In an institution that enforces uniformity across genders, the cooperative reliance among female bandmates is sustaining. “Without the female group, who do you have to lean on? Who do you have to tell your stories to if something happens? You can’t just go to another male in the band, because they won’t understand what a female’s going through. Only a female understands what a female’s going through.”

Aysja has a bandmate who is one of her best friends. She asks me not to print her name, but tells me they sit together on the bus and room together in the hotel; they talk to each other about everything and stand up for each other when conflicts arise. Aysja asks me if I’ve ever seen the ’90s TV sitcom Martin, featuring Martin Lawrence and Tisha Campbell as his girlfriend, Gina, who is best friends with Martin’s archnemesis Pam. “Pam and Gina? That’s what we’re like. We always have each other’s back.” I did watch Martin, when I was in my twenties like Aysja is now, but I tell her I can only imagine the bond between Pam and Gina, or her and her bandmate. That I can’t know what it’s like for a woman to make it in the band world, let alone to shoot for being the best in that world. “‘The best’ isn’t real to me,” Aysja corrects me. “You want to be a leader.” She explains that Southern is a leader among HBCUs, “and in my section, the leaders take a higher responsibility than anyone.”

Aysja has the responsibility and the skills of a section leader, not just an assistant. According to Derrick, “The only reason she’s not section leader is because she’s a girl and they don’t want the section leader to be a girl.” Aysja, for her part, won’t say an ill word, even when Derrick tells her he watched Southern perform Lil Wayne’s “Piano Trap” and noticed the section leader was taking breaks while she played straight through. She just smiles and nods. “I play from the heart,” she says. “Not being section leader doesn’t phase me, due to me seeing myself higher than that title.” She redirects the conversation away from criticizing her male counterparts and toward what’s required to become a leader among them. The right mindset. Positive thoughts. Being on guard. Having each other’s backs. While band presents itself as a meritocracy, in actuality women must not only play by the rules of masculinity but do better than men, without protest or even acknowledgment of its patriarchal design.

In the history of The Roots of Music, no graduate has excelled within the strictures of band more than Aysja, and Derrick beams with pride in her presence. When the three of us get up to go watch the Roots band rehearse, I ask him if he wants to introduce Aysja to the current students. He laughs. “She’s assistant section leader at Southern. Went to Walker. Come from Roots. I guarantee you she needs no introduction!” Down in the rehearsal room, Aysja greets Darren and LeBron, then promptly walks over to the mellophone section to help the kids with their parts.

Darren’s own dream of graduating from Southern went unfulfilled. At the end of his second year, a minor dispute with the band director quickly escalated and Darren was put on suspension. He turned to his father for advice and was told to withdraw and come home. “I was lost,” Darren remembers. “My world was flipped upside down.” He started helping out at St. Aug and seeing a counselor, unsure of his next move. Ultimately Darren got himself resituated at another HBCU, Talladega College, outside of Birmingham, Alabama, where an infusion of St. Aug talent was getting the Marching Tornado Band off the ground. After graduation, he came home to lead the Roots band at twenty-three years old.

Darren and LeBron are friends, roommates, and partners in a clothing brand called ELEV8N (pronounced elevatin’). They’re very different, but they’ve been through a lot together, including surviving a drive-by shooting outside their apartment. That the teachers at The Roots of Music share comparable experiences with their students is key to the organization’s success. Darren and LeBron have survived and thrived through challenges that altogether too many kids in New Orleans face, and they’ve gone on to do things that earn them respect with their students, peers, and mentors. This is perhaps the greatest and least quantifiable benefit of participation; finding love in a competitive space where, ideally, everyone strives to be the best.

LeBron has a song about this called “With My Friends,” released under his stage name, King Bronze. I watched him film the video outside the Roots facility on a chilly evening in November 2018. Surrounded by dozens of students, he leads them in lip-synching the refrain:

When you fall you gotta get up again

Loss after loss you feel like you can’t win

I pray so hard to clean up all of my sinsI just wanna live a good life with all of my friends . . .

When the beat drops, the kids smile and egg on King Bronze as he raps a solo verse:

Friends

The ones who you supposed to depend on ’til the end

The ones who build loyalty that never ever bends

The ones you feel you can really really call your mens

Cause it’s rare to see young Black kings living heavenly

They rather take the young Black kings, book them with felonies

They knock me downI got back up stronger, that’s what it gotta be

I do this for all the ones behind that wall who can’t even see they kids

And you think this how we suppose to live?

Man, our people cried so many tears

They faced so many fears

So when you get out there, show them we here . . .12

Under conditions of mass incarceration and other structural racisms designed to knock Black people down, LeBron pens an ode to loyalty and solidarity, strength and friendship, to “show them we here.” He sings of fraternity with fellow men, but the video shows this extending to girls who choose to enroll in The Roots of Music, singing and playing alongside the boys, negotiating the scripts of Black masculinity that condition the lives of everyone in band.

On February 23, 2020, right before the pandemic made gathering together unsafe, I joined the Roots crew before the Bacchus parade, the highlight of their Mardi Gras season. “We practiced hard for this,” LeBron announces at rehearsal. “It’s time to go out there and execute and have fun.” The kids are adjusting each other’s uniforms, draping their white spats over their black boots, and trying to put on their gold helmets without messing up their hairdos.

“You are the Beyoncé. You are the Migos,” shouts LeBron. “Whoever else you listen to.”

Someone yells, “Kendrick!”

LeBron smiles. “Kendrick Lamar. Whoever. You’re the performer. You’re The Roots of Music. Do we understand that?”

“Yes, sir!” everyone shouts in unison.

Darren is inspecting each section lined up in a row. “Band, we ready?”

“We always ready!”

“Band, we ready?”

“We always ready!”

The drum major blows his whistle, directing everyone onto four yellow school buses. We drive across town and unload in a supermarket parking lot that serves as a staging area for the parade. For Bacchus, the site transforms into a battleground for rival bands to blow against one another. In front of a tightly packed crowd, Southern battles Talladega, starting off with Lil Wayne’s “Piano Trap,” with Aysja playing all the way through. The Roots of Music squares off against Alice Hart, one of the few middle schools with a full marching band. The staff asked me to bring my camera, so I position myself between the bands, where the drum majors face each other, and film them calling out songs in alternating order. After half a dozen songs, the directors congratulate one another and line up their bands for the parade.

St. Aug is setting up ahead of us and I go say hello to some recent Roots graduates. Tuba player Tyran Battiste is chatting with his bandmates and I interrupt them to congratulate him on making the band. It’s awkward for a second, maybe because teenagers are awkward, and maybe because Tyran is embarrassed to greet a middle-aged white man with a camera who is a stranger to his friends. We’ve spent hours together, going over Tyran’s homework in the tutoring room before practice, or just chatting about Fortnite or whatever book he’s reading. Six months since graduating from Roots, he’s still kind, gentle, and funny. But I see how he’s becoming a man, specifically a St. Aug man, more formal and polite. We shake hands goodbye and I rejoin Roots, marching onto the parade route, propelled by the rhythm of the cadence, until the first song arrives with a blast, provoking a joyful whoop from the crowds behind the barricades. We head off into the night, the kids holding their instruments straight, their knees interlocked in step, a model of discipline and swagger.13

In an interview with Tyran’s parents, Keanon and Tiffany, I asked them how they felt about push-ups and other punishments in band. “It’s different in a Black household,” Keanon responds. He doesn’t know me well yet so he’s choosing his words slowly and carefully. “I don’t know, you know? We live in two different worlds.” I nod in agreement. “And we live in the same world but what I have to look behind my back for is not what you have to look behind your back for.” The same world affects my teenage daughter and me differently, along the lines of race as it intersects with gender. “What I have to prepare my kids for is what you don’t have to prepare your kids for. And it sucks.” For Keanon, discipline and competition are necessary for raising a son in a society that devalues vulnerability or equates it with weakness for Black men. He tells me life is tough, and then explains why the teachers are tough on the kids.

There’s much more here for me to try and understand, knowing I never fully can. Derrick has been on me to write a book, and photographer Abdul Aziz has agreed to collaborate. Even as we make preparations for Roots’s fifteenth anniversary, this part of the story is just beginning to be told.

This essay first appeared in the Sonic South Issue (vol. 27, no. 4: Winter 2021).

Matt Sakakeeny is associate professor of music at Tulane University. He is the author of Roll With It: Brass Bands in the Streets of New Orleans and coauthor of Keywords in Sound and Remaking New Orleans: Beyond Exceptionalism and Authenticity. Matt is a board member of The Roots of Music and is writing a book about music education in New Orleans with photographer Abdul Aziz.

Header image: The Roots of Music practice parade, February 11, 2020.NOTES

Thank you to Abdul Aziz, the Batiste family, LeBron Joseph, Aysja Mallery, Darren Rodgers, Derrick Tabb, and everyone at The Roots of Music for their generosity and friendship. Thanks also to Kyle DeCoste, Suzanne Raether, and Lee Veeraraghavan for their comments on an earlier draft, and to the reviewers and editorial staff at Southern Cultures for their feedback and assistance. This research was initially sponsored by a grant from the Spencer Foundation.

- Quotes for this essay are taken from observations of band rehearsals and performances and the following interviews: LeBron Joseph, in discussion with the author, June 11, 2019; Derrick Tabb, in discussion with the author, June 6, 2019 and June 15, 2021; Darren Rodgers, in discussion with the author, February 5, 2019; Jaron Williams, in discussion with the author, December 13, 2018; Aysja Mallery, in discussion with the author, June 15, 2021; and Keanon Battiste, in discussion with the author, June 6, 2019. This essay is part of a larger project and participants are protected by my university’s IRB protocols. Anyone named has agreed to participate in the study. Several children are not named in order to protect their identities.

- bell hooks, Yearning: Race, Gender and Cultural Politics (Boston: South End Press, 1990), 58; Mark Anthony Neal, New Black Man: Rethinking Black Masculinity (New York: Routledge, 2005); Darius Bost, La Marr Jurelle Bruce, and Brandon J. Manning, “Black Masculinities and the Matter of Vulnerability,” Black Scholar 49, no. 2 (2019): 4.

- Bost, Bruce, and Manning, “Black Masculinities,” 6.

- For an analysis of racial segregation in contemporary New Orleans charter schools, see Frank Adamson, “Educational Inequities in the New Orleans Charter School System,” SCOPE, November 2016, https://edpolicy.stanford.edu/library/publications/1572.

- Christina Lee and Regina N. Bradley, “Our Band Is Better than Your Band,” August 2019, in Bottom of the Map, produced by Regina N. Bradley, Floyd Hall, Stephen Key, and Christina Lee, podcast, 47:16, https://www.bottomofthemap.media/episodes.

- Beyoncé qtd. in Fredara Mareva Hadley, “Beyonce’s ‘Homecoming’ Film Doubles Down on Her Joyous, Unapologetic Blackness,” Billboard, April 17, 2019, https://www.billboard.com/articles/news/festivals/8507563/beyonce-homecoming-film-coachella/. Hadley, an ethnomusicologist and FAMU alum, makes a provocative comparison between Homecoming and Aretha Franklin’s “Amazing Grace,” a gospel performance recorded in a Baptist church in 1972: “Black churches and HBCUs are two of the most venerable institutions within Black communities and both Aretha and Beyoncé possessed a keen sense of how to honor the spaces and the people without sacrificing their own musical alchemy.”

- Jacqui Malone, “The FAMU Marching 100,” Black Perspective in Music 18, no. 1/2 (1990): 62; William Patrick Foster, Band Pageantry: A Guide for the Marching Band (Winona, MN: Hal Leonard Music, 1968), 29, 32; Richard L. Walker Jr., “The Life and Leadership of William P. Foster: The Maestro and the Legend” (PhD diss., Indiana State University, 2014), 143; Regina N. Bradley, Chronicling Stankonia: The Rise of the Hip-Hop South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021).

- “At a Glance–School Profile,” St. Augustine High School, accessed July 17, 2021, https://www.staugnola.org/apps/pages/index.jsp?uREC_ID=1801329&type=d&pREC_ID=1969743; Matthew O’Rourke, Between Law and Hope: St. Augustine High School, New Orleans, Louisiana(New Orleans, LA: St. Augustine School, 2003), 15.

- O’Rourke, Between Law and Hope, 101; “Bended Knees,” St. Aug Marching 100, May 29, 2017, You-Tube video, 56:45, https://youtu.be/5iS9ZydVLi4.

- Foster, Band Pageantry, 8.

- Video footage of the bands at the 2019 BoomBox Classic can be accessed at “Southern University Human Jukebox Marching In & Out Boombox Classic 2019,” Human Jukebox Media, November 17, 2019, YouTube video, 17:15, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yzA1a2VDw-ZA&list=PLyLPqhafxEWcdFd4tICvTWLAoQv9mWEGp.

- King Bronze, “With My Friends BY: King Bronze (Official Music Video),” Mfcool Productions, December 19, 2018, YouTube video, 4:46, https://youtu.be/srIKbngbPzM.

- Video of The Roots of Music performing in the 2019 Mardi Gras parades can be accessed at “The Roots of Music Mardi Gras 2019,” mattsak12, March 31, 2019, YouTube video, 48:05, https://youtu.be/xBSpkae0MsU.