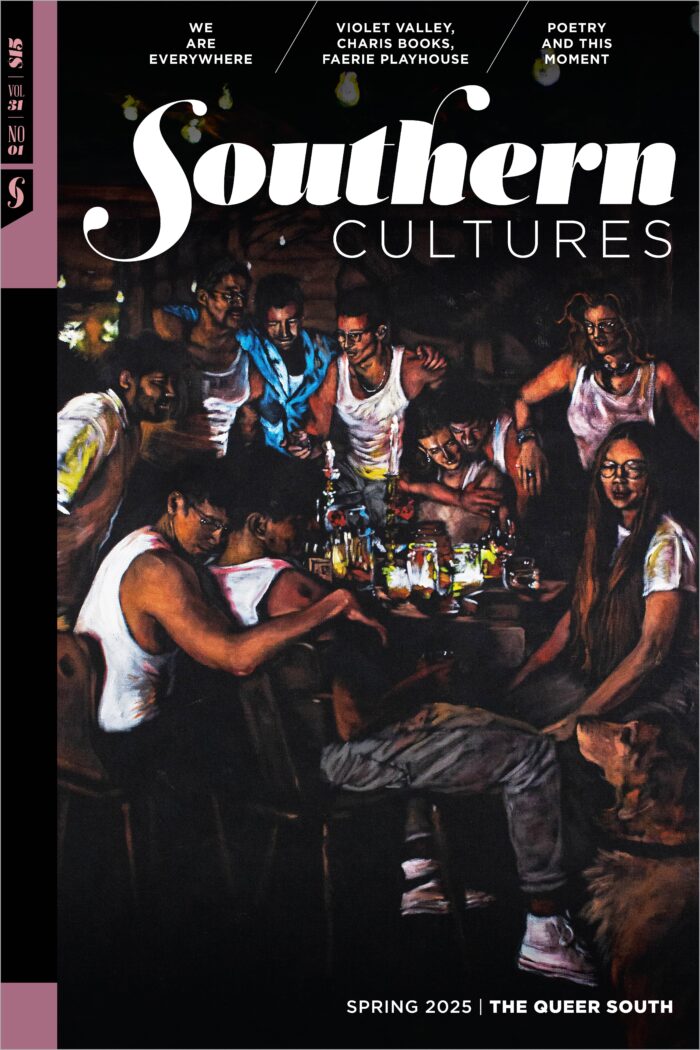

Jimmy Wright’s many collectors and enthusiasts quite reasonably think of him as a New York painter. Wright (b. 1944) has lived and worked in New York City since 1974, and since the early ’90s he has been celebrated for his incisive self-portraits and his luscious paintings and pastels of sunflowers. The New York Times described Wright’s sunflowers as “untrammeled images so deeply expressive that they make van Gogh’s florals look decorous by comparison,” and the New Yorker said they are “passionately unkempt . . . not exactly unsentimental, but full of a writhing, macabre lushness.”

What might come as a surprise is that the geography of Wright’s past has more to do with the Midwest and the South than the environs around the Big Apple. His artistic sensibility is marked by a history that extends, by way of Illinois, back to his upbringing and early education in Kentucky. Born in rural Kentucky, Wright attended the Aspen School of Contemporary Art in Colorado in the summer of 1963, meanwhile studying art in Kentucky at Murray State College. In 1964, Wright moved to Chicago to attend the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), and he lived and made art there for four formative years.

As a young, quickly maturing painter and printmaker, Wright was part of the hotbed of activity that spawned Chicago’s imagist movement. He was close friends with the members of the group that called itself The False Image, especially Philip Hanson, Christina Ramberg, and Roger Brown. “Fellow student, Jimmy Wright, and I had become close friends,” Brown wrote later, reflecting on the mid ’60s. “We had a lot in common.” Both were southerners with the same religious background and worked in the school storeroom.

Wright graduated with honors from SAIC in 1967 and he returned for a semester of grad school. With a travel fellowship from SAIC, he left on an overland journey through Europe into Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and finally Nepal and India, where he stayed for four months. The visual impact of India, as well as its social and cultural climate, made a deep and lasting impression on Wright. In women’s veils, Wright found an image of repressed sexuality that he identified with from his own conflicted past as a gay youth stealthily growing up in the religious US South. “It was a kind of repression I was so familiar with,” says Wright.

Back in the States, in the autumn of 1969, Wright moved from Chicago to Carbondale, Illinois, to attend graduate school at Southern Illinois University, from which he received his MFA in 1971. A major catastrophe befell Wright in 1970 when his house burned down, taking with it all the paintings he’d made while in Chicago. Left was a scattered portfolio of drawings and prints and a brain full of remembered artworks. You can see singe marks from this inferno around the edges of the handful of remaining Chicago-era pieces, poignant reminders of the tenuousness of material existence. Wright stayed on at Carbondale for a few years, teaching, painting, and rebuilding. Wright’s decision to settle in New York in 1974 proved to be an excellent one. He took to the city immediately, painting luminous night studies of the cityscape, and creating a portrait of the World Trade Center, even as the Twin Towers were being completed. Wright dove into New York’s nightlife with gusto, and his sketchbooks include uproarious images of disco club scenes; his etching Club 82 (1974) looks something like Studio 54 as it might have been rendered by Max Beckman.

By the early ’80s, Wright was painting images that directly confronted the complexities of his southern childhood. Baptism at Rives, Baptism at Pilot Oak, Baptism at Obion River, and Snake Service (all 1980) deal slyly with the homoeroticism of certain religious rituals, while The Confession (1980), a major entry in his oeuvre, once again finds the influence of Ensor helping to shape a wickedly sharp group scene in which heads resembling Elvis and Jesus dot the crowd. A special project at the beginning of the ’90s led to a group of softer, more emotionally vulnerable monoprints (some compiled into two artist books) exploring his grandmother’s small hometown in Tennessee.

Wright’s painting changed dramatically in the early ’90s. With the diagnosis of his partner with AIDS in 1988, Wright began work on his first sunflower, a magnificent, huge, heavily impastoed oil, dominated by browns and tans. A newfound love of pastels has resulted in many radiant sunflowers and bunches or baskets of other flowers, sometimes joined by luna moths, and this topic has also been the germ for a series of larger oil paintings. Taken with Wright’s striking self-portraits, executed in the same media as the sunflowers, these flower paintings have earned Wright an international reputation. But as Grace Glueck wrote in her New York Times review of Wright’s 2001 solo show at D.C. Moore Gallery: “These are not flowers as decoration but symbols of a deeper engagement with the vagaries of nature and self.”

The sunflower paintings bring to bear the immense wellspring of experience of a divergent Chicago imagist steeped in memories of world travel, a rich life, and personal and artistic tragedy. Wright is an artist whose generosity of spirit and devilish sense of humor have kept his work from becoming ingrown or losing its vigor.

—John Corbett

Originally published in “RADIANT: Jimmy Wright, An Overview, 1963–2004,” on the occasion of a 2004 solo exhibition at Corbett vs. Dempsey in Chicago, this introduction has been condensed and lightly edited for publication.

I acquired my first secret boyfriend at twelve years old, another gay farm boy—a classmate I met in junior high and whose grandfather was a hunting partner of my father’s. During four years of high school, I had a second secret boyfriend, a town boy, a church musician, an athletic swimmer, and an Episcopalian whose older brother was also secretly gay. I think of my gay childhood as being in a time capsule, a world that no longer exists: the Jim Crow South, a land-based agricultural, patriarchal old family that, though financially barely middle class in the 1950s, had social standing and privilege.

My boyfriends’ lives took dramatic paths from my own. The first one called me in a panic when he was drafted during the Vietnam War. I coached him on “checking the box” and answering questions during the draft interview. He married, fathered a child, and went through a bitter divorce and custody battle, then settled into a domestic relationship with another gay man. My second boyfriend tragically committed suicide on a visit home from graduate school. His older brother died of AIDS.

On Halloween night, October 31, 1966, my best Kentucky college friend, a talented painter from Paducah and a visible sissy, was violently murdered while visiting me during my time at art school in Chicago by a James Dean look-alike hustler from Appalachian Eastern Kentucky. Farm culture taught me to shoulder responsibility, no matter how grim or heavy. I identified my friend’s body at the Cook County morgue, signed the death certificate, called his parents, called my parents, was a pallbearer at the Pentecostal funeral and burial, testified before a grand jury, and represented his parents at the murderer’s trial.

On Halloween night, October 31, 1966, my best Kentucky college friend, a talented painter from Paducah and a visible sissy, was violently murdered while visiting me during my time at art school in Chicago by a James Dean look-alike hustler from Appalachian Eastern Kentucky. Farm culture taught me to shoulder responsibility, no matter how grim or heavy. I identified my friend’s body at the Cook County morgue, signed the death certificate, called his parents, called my parents, was a pallbearer at the Pentecostal funeral and burial, testified before a grand jury, and represented his parents at the murderer’s trial.

In my small town in the early 1960s, there were “old bachelors” and railroad men. The old bachelors were from prominent families with social positions and had university degrees. One was the subject of gossip for his old money wealth and for giving drinking and card parties on the family farm estate; another collected antiques from New Orleans and Memphis, creating a home that was an oasis of art and crafts; another, a respected professional who owned a considerable amount of stock in the local bank, befriended railroad men, frequented roadhouses, and drove the local diner’s cook on errands about town, a white man and a Black man visible to everyone in the town as they passed by in the front seat of an immense dark blue Buick.

I heard about the first bachelor from my father. Folks from Mississippi Delta plantations drove up from Memphis to spend the weekend at the card parties. The bachelor was a tall, handsome silver fox and a ladies’ man. The second old bachelor became a lifelong friend and was the first to collect my art and invite me to formal dinners prepared by a cook and served on fine China and silver. My early art hangs in a family member’s home. He recommended authors and loaned me books. I met the young man who made discreet visits using only the back door at night. The third bachelor was a character from a Flannery O’Connor story. I would never visit him alone; I would always be with bachelor number two. His stories smelled of danger, scandal, and a visit from the sheriff or, worse, a helpful call by a well-meaning Christian to tell my father his son was queer.

My hometown was once a significant depot for freight and passenger train traffic on the Illinois Central Railroad’s route from Chicago to New Orleans. In town was an old hotel built in the 1920s, the heyday of train passengers and crews. Serendipitously, in 1991, the artist Paul Cadmus introduced me to the heirs of a chain of southern railroad hotels, the siblings Ruth Ford, the Broadway star, and the Surrealist poet Charles Henri Ford. Ruth Ford had spent summers as a teenager in my hometown.

By the 1950s, the Earl Hotel was in a downward spiral. The railroad men, primarily brake and flag crews, would overnight at the hotel, though some stayed over on extended visits. The one I met, a passenger in Bachelor Number Three’s car, was the strong, silent type, a handsome, hyper-masculine thirst trap. He was the type of man that, as a five-year-old attending Sunday church service, I would look at and silently puzzle how a handsome man could marry such a plain, homely woman. Thirteen years later, as a precocious eighteen-year-old, I could only fantasize about why the handsome brakeman had been hanging out at Bachelor Number Three’s house, a plain, homely man.

Similarly, sitting in church and watching the theatrical presentation of the baptismal service in a built-in water tank framed by velvet curtains, with heavenly clouds painted as the backdrop, I could envision the butch farmhand deacon in waist-high rubber hip boots and a wet, clingy dress shirt with rolled-up sleeves, grasping me by the waist and dunking me underwater as the Holy Spirit hovered above, bathing both the deacon and me in rays of divine bliss. During a week-long summer Bible revival, the guest song leader from Mississippi resembled a 1950s prototype of Joel Osteen, sporting a wavy Elvis hairdo—the longest a man could wear his hair while still being deemed masculine, although still on the verge of trashy. He wore a sleek grey suit tailored to perfection, and while using his entire body to set the pace for the a cappella service, he flashed an ever-ready, radiant smile as he led the invitation song.

What a fellowship, what a joy divine

Leaning on the everlasting arms

What a blessedness, what a peace is mine

Leaning on the everlasting arms

Indeed. The plan was for me, upon high school graduation in 1962, to attend Bible college in Nashville. I don’t remember applying, just remember that I graduated with my acceptance letter in hand. I was suspicious about being an art major in a fundamentalist Bible college. So, borrowing the family car, I drove solo the forty miles to a small town overlooking the river for a high school art portfolio review conducted by the regional state college. The art department chair sported a tight, freshly permed hairdo, horned-rimmed glasses, and giant silver cuffed bracelets on each wrist. She smelled of breath mints and tobacco smoke and wore a fixed “I can see right through you” expression. What she saw was my radiant gay self. I drove home with a lifesaver, the handwritten instructions that led to my first-ever act of rebellion: I went to the state college on a Regents Scholarship.

In the 1950s South, gay people who passed were described in the community as being “old bachelors” and “old maids.” At that time, no openly gay faculty member could hold a college position. So when I arrived to campus, I came across two old maids who were “roommates.” One was the formidable chair of the art department who had recruited me; the other was the chair of the home economics department. Their colleague, my English professor, fed me extracurricular reading of William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, Eudora Welty, and Tennessee Williams. On my own, I found Horton Foote and the use of the bittersweet images of “down home” as a personal visual narrative.

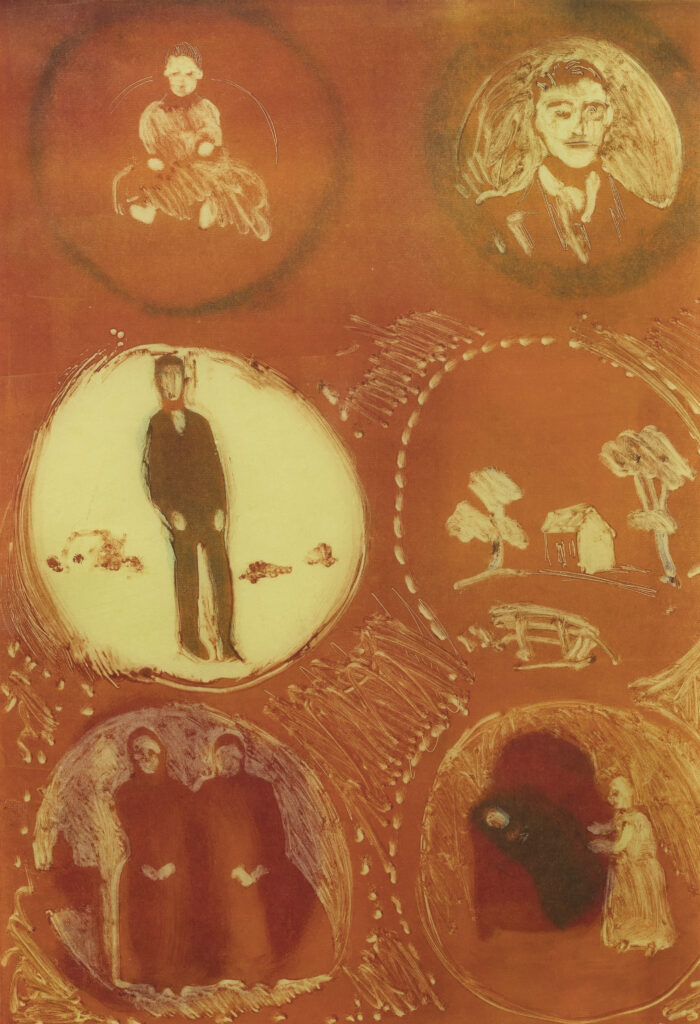

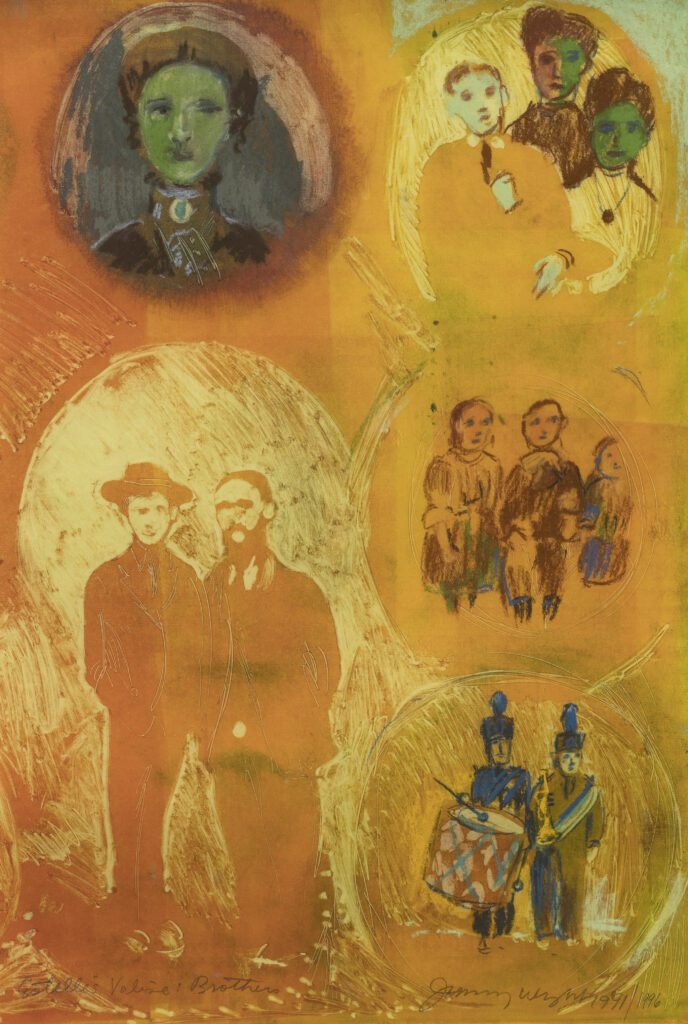

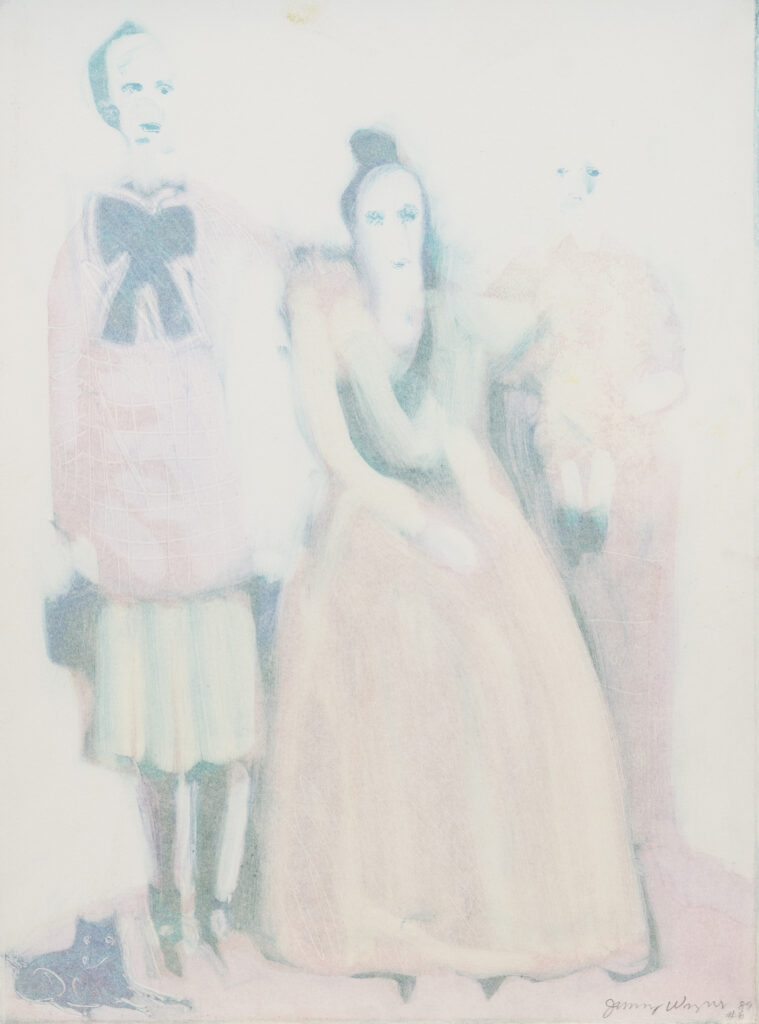

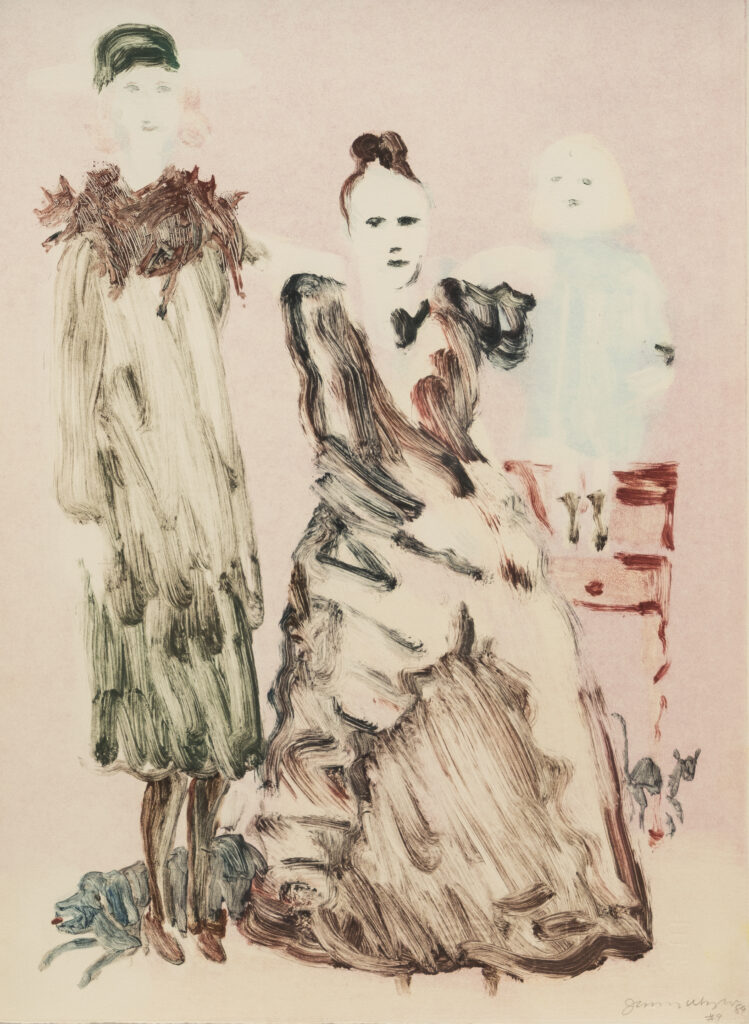

Down Home became the name of a solo exhibition of my work at Chicago’s Corbett vs. Dempsey Gallery in 2023. I created the series of monotypes, shared in these pages, during the 1990s while working at the Lower East Side Print Shop near my home of forty-three years in Manhattan. My recollections become an exaggerated, tinted, distilled truth during the creation and printing of the monotypes. They are the visual reflections of a sissy kid—me—growing up on a frontier family farm and in the small railroad communities of Western Kentucky and Tennessee in the 1950s.

Jimmy Wright, a Fulton, Kentucky native, received an Honorary Doctor of Arts from Southern Illinois University in 2024. His large Bowery studio is home to five decades of work, including a series of billowing floral paintings and a drawing series that chart his engagement with the subculture of gay life on the Lower East Side before the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

John Corbett is a writer, curator, and producer based in Chicago. He is co-owner of Corbett vs. Dempsey, an art gallery and record label. Corbett’s most recent book is Pick Up the Pieces: Excursions in Seventies Music (University of Chicago Press, 2019).

Header image: Detail from Estelle’s Valise: Turkey Creek Cabin, 1991. Monotype, 30 x 22 in. All images courtesy of the artist and Corbett vs. Dempsey gallery.