“In general, local, artisanal, values-based makers are in constant struggle to validate their craft. Textiles, especially, are up against large global labor markets that have trained consumers to buy more disposable goods for less money.”

After a career as a textile buyer and production manager in New York City’s Garment District and after seeing so many factories shut down and skilled workers lose their jobs to overseas competition, I am on a mission to preserve the skill of sewing in our domestic manufacturing economy. For me, that means providing good jobs and a new model for production, as well as supporting the independent designer’s scaling production needs.

Since 2010, I have been the owner and CEO of Sew Co., an industrial sewing manufacturing facility in Asheville, North Carolina. I built a partnership with The Oriole Mill, a boutique industrial textile mill, in which our two separate businesses acted as a single vertically integrated manufacturing facility. The Western North Carolina community, with its industrial manufacturing history, has proven to be an ideal location for Sew Co. to embrace both craft and industry. I was lucky to have had veteran textile manufacturing workers teach me their methods and systems, and these skills have now been passed down to Sew Co.’s younger employees.

Our entire crew practices radical financial transparency to create a culture of agency and empowerment. As a founding partner of the Carolina Textile District (CTD), we work cooperatively with our local “competitors” to strengthen our industry collectively. The CTD has established an industrial sewing training program with our local community colleges and has founded an ancillary enterprise, Material Return, to address local, circular solutions to our region’s textile waste. We gratefully find ourselves embedded between this progressive manufacturing community and the vibrant craft community of our region, established by the legacy of Black Mountain College and organizations like Penland School of Craft, Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts, and the Center for Craft.

We love living at the intersection of art, education, and industrial manufacturing. As a result, our team of skilled artisans focuses on quality and creativity. Because we pay a living wage, we are rarely able to make the most affordable bid. Instead, we compete on craftsmanship, ethics, and service.

Sew Co. develops and produces sewn goods, ranging from shower curtains to designer garments, for a wide range of brands. Before COVID, we were a team of eight. During COVID, we produced masks and gowns (partly due to a collective contract with the CTD partners and the State of North Carolina), while our home decor client sales went bananas. We grew to a team of eighteen. Our mission to preserve the skill of sewing domestically felt validated.

The culture and allure of Asheville is built on creative spirit and independent entrepreneur-ship. In the past few years since COVID, we have seen our city’s economic landscape change dramatically, with property values soaring out of reach for the young working class and the living wage increasing more than 20 percent. Small businesses like Sew Co.—already competing with the global labor market—have struggled to maintain break-even profitability. We have been working against the current of cheap labor and disposable textiles for fourteen years. As a contractor, our margins are threadbare, yet we bear the bulk of the problem-solving, physical labor, and integrity of the product.

In addition to repaying Economic Injury Disaster Loans, the financial and emotional devastation of Hurricane Helene in September 2024 is a compounding hurdle that is hard to see past. Our studio and retail space is within the River Arts District of Asheville, one of the areas hardest hit by the storm and one that relies heavily on a tourism economy. The local building owners who developed the district are essential to its affordability and cultural survival. I’m left asking, how can the community afford to rebuild without large corporate funding that could homogenize our culture? How can we recover with a large strategic model for progressive and creative placemaking?

With living wages increasing and the cost of raw materials rising, we are struggling to retain and recruit clients, and therefore our staff. Clients are faced with juggling their values and their bottom line, and we are faced with the constant question: What is it worth?

Assessing Worth

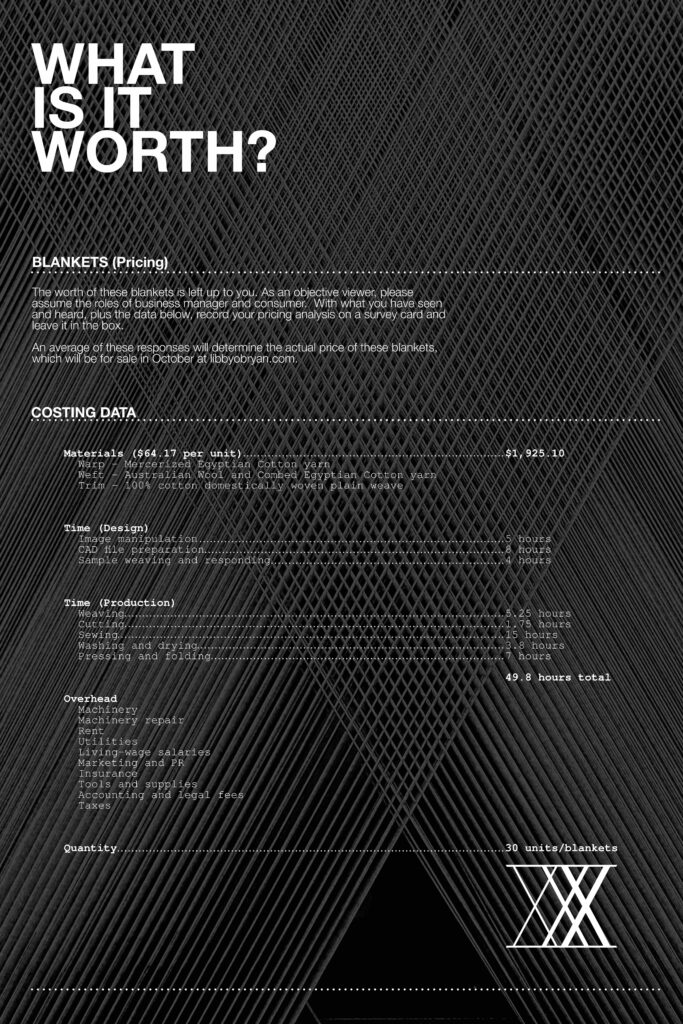

We explored this question in our installation, titled What is it Worth?, created as part of the 2015 Made in wnc exhibition for the Center for Craft. Curated by Marilyn Zapf, with the help of my team at Sew Co. and collaborators under my direction, the installation examined the process, product, and value of textile manufacturing. We produced thirty blankets, titled Blanket (Product), at Sew Co. and The Oriole Mill, and documented, choreographed, and filmed each stage of production—design, weaving, cutting, sewing, finishing, and fulfillment—which we titled Blanket (Process). In an effort to acknowledge industrial production as a poetic process, actions regularly performed at Sew Co. became exaggerated, extrapolated, and abstracted. To me, there is beauty in the manufacturing process—in the repetitive, collective choreography, in the making of multiples with meditative muscle memory.

In textile production, we first pull fiber from an animal or plant, then spin it back together as yarn, cut those yarns, then weave or knit them together again. That fabric is then cut before being sewn together once more. What is it Worth? connects, disconnects, reconnects, separates, builds up, breaks down, floats, fumbles, balances, and flutters.

Do high-quality goods have a market in our disposable economy? Will consumers prioritize material investments? Do consumers desire meaningful experiences with the things they buy? Is there a balanced value exchanged for responsible, skilled, and artful processes?

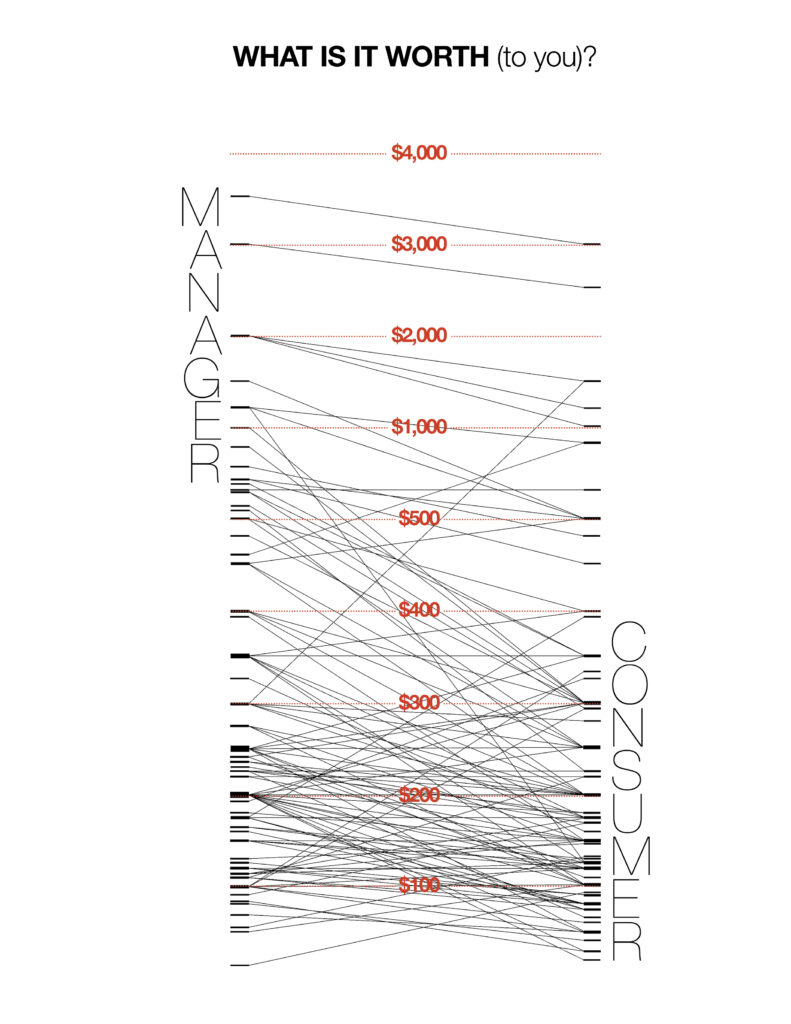

In the accompanying video, blankets-in-progress pile up, hiding the sewer, over and over again. The blankets are washed, pressed, folded, shipped, and eventually find their way back to the earth, floating in the river. It is up to the viewer, as a member of our culture, to define the meaning of this project and assess its relative worth. To illuminate the costs and labor involved in producing these blankets, the audience was asked to evaluate the data and “crowd price” the blankets. Viewers were presented with the costing data and asked to determine a price for each blanket. A graphic was created to show the dollar amounts suggested by business managers and consumers.

We collected 142 responses over a four-week installation. Averaged results included business managers pricing the blanket at $344.76, and consumers on average willing to pay $283.80. I chose to honor the consumer’s budget and sold the thirty blankets at $283.80, in hopes that the blankets found owners who valued their worth. Reflecting on this project ten years later, given the increases in cost of living, national inflation, and the prices of natural materials and imports, I estimate the cost of making the blankets today would be nearly double.

Values-based Work

Industrial production of textiles has become ubiquitous in our lifestyles of constant consumption. The voice of the maker (whose touch is still essential, even in a factory setting), the celebrated anomalies of process (which still occur in mechanization), and the perceived value of the object have diminished. In turn, we have a depleting environment, a deepening socioeconomic divide, and a de-skilled domestic labor force. Our small batch of thirty blankets, which hung in the gallery adjacent to the video, could represent a microcosm of any industrially produced textile. The repetitive nature of their construction processes may be similar, but their embodied energies are different. These blankets were created with concentration and care. The intentions, attentions, and emotions of the farmers, spinners, weavers, sewers, and designers are embedded in the object. It holds deep cultural meaning for the makers. Does the embodied energy of the blanket resonate for the consumer experience? Do high-quality goods have a market in our disposable economy? Will consumers prioritize material investments? Do consumers desire meaningful experiences with the things they buy? Is there a balanced value exchanged for responsible, skilled, and artful processes?

I believe objects hold an embodied energy that is cultivated as it is being created. Objects can be made with renewable, regenerative materials, as opposed to ones ravaged from the earth. Objects can be made with caring, attentive, respected hands as opposed to oppressed, disgruntled labor. These objects hold a memory that we can feel when we engage with them. When we put cloth on our bodies, we adorn ourselves with our values and our complicity in various production practices.

In the decade since this project was executed, values-based buying has fluctuated. In times of crisis, we’ve seen spikes, but in general, local, artisanal, values-based makers are in constant struggle to validate their craft. Textiles, especially, are up against large global labor markets that have trained consumers to buy more disposable goods for less money. The results of the crowd-priced blankets gave me insight into the explicit understanding consumers have of the cost of materials, of labor, and of US manufacturing. We may understand and hold certain values in our minds but are unwilling (or unable) to live those values with our available resources. Also, we hold an implicit bias for the way we want to consume: we want more for less.

For me, the question has since remained “What is it worth?,” but I am less concerned with the opinion of others and more focused on my personal self-worth, adhering to my principles against so much adversity. I have worked tirelessly through pregnancies and pandemics. I have had to lay off good friends. I have had to fight for every low-margin sale. My commitment to my values and meaningful work has put me at odds with huge corporations and economic systems that I have no chance of changing. So what is all the effort worth?

The real worth of empowered employees creating meaningful products is the subtle ripple effects they have on our culture. Slow and local food movements have paved the way for textiles—also an agricultural commodity. Consumers are better informed and are asking more questions about the origins of clothing and home goods. They crave a more meaningful experience. The real worth of values-aligned work is finding self-worth through the process.

Trained in fashion design at the Fashion Institute of Technology, business administration at the University of San Francisco, and fine art at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Libby O’Bryan melds her hybrid background into a conceptual art practice. Her work has been exhibited at the Chicago Cultural Center, South Eastern Center for Contemporary Art, Cameron Art Museum, the Penland School of Crafts Gallery, the Knoxville Museum of Art, and the Center for Craft.