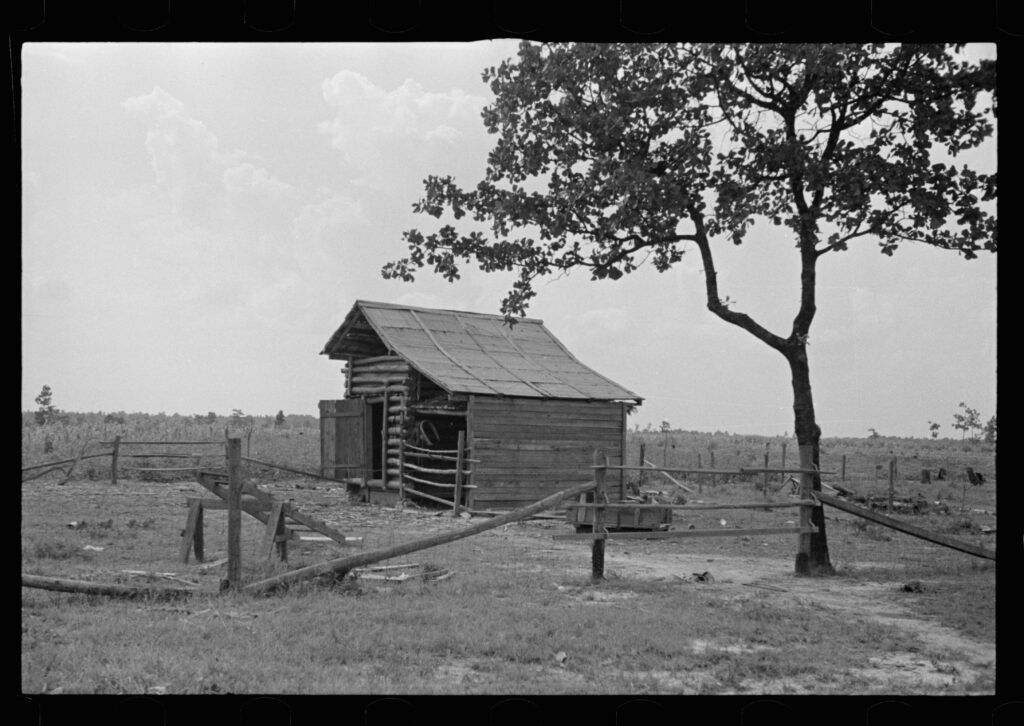

I come from a long line of people whose lives seemed straight out of a Walker Evans photograph. Landless whites, rootless, disposable—“white trash.” It’s hard to create home from contingency, or a feeling of belonging from worthlessness.

They say southerners are people defined by place, but I never believed it. At least it wasn’t true of me. Mississippi never loved me, and I never loved it back. The muddy Mississippi River stole my uncle’s young life, and hardscrabble dirt eked out the sweat and lifeblood of my family for generations.

When southerners talk of home, they often refer to a “home place,” some piece of real estate filled with memories and longing. But while both sides of my family yearned to own land, they never found home.

In 1953, when my father, William Monk, was seventeen, he threatened to rob a bank unless my sobbing grandmother would sign the papers for him to enlist in the Army. Tired of shoeless winters, being a good-looking boy with no money for dates, elected junior class president but no future ahead, he knew the Army was his ticket out of poverty—or at least out of Mississippi. He pried at his mama’s weak spot—anything but robbing a bank. And he won.

My grandmother was a plain-looking woman, but with a heart so kind that nobody much paid attention to her looks. She would die at fifty-one of her third heart attack—the result of poor diet, bad teeth, and a hysterectomy before she was thirty. She became my grandmother when she was thirty-seven. Many years after she died, her aged sister-in-law would tell me, “Your Mo Mo was the ugliest woman I ever saw.” And I thought to myself, Look who’s talking. But I heard my grandmother say, Don’t talk back to your elders.

Mo Mo Monk was short and slight, but with hips wide enough to tote her twin brothers on either side. Her name was Elizabeth, but her brother’s lisp rechristened her “Lil’ Bet,” and the name stuck. She married at thirteen, with her mother’s urging, so there would be one less mouth to feed. It was the Depression and hard to raise ten children by sharecropping on Jefferson County’s red dirt.

“I didn’t really love your daddy when I married him,” she later told her son, my uncle Jesse, “but I grew to love him.” Her daddy, Lum Scott, didn’t want a nineteen-year-old man running away with his precious oldest daughter. He threatened to kill John Monk if he came sniffin’ around Lil’ Bet again. Lum Scott was a mule skinner, and he knew how to beat men and animals into submission. Lum believed that the best way to train a mule was with a two-by-four upside the head: first, you had to get the mule’s attention.

John’s daddy, Lige Monk—short for Elijah or Elisha, we never knew—was not to be outdone. Ol’ Lige told Lil’ Bet to put a piece of paper with the number sixteen inside her shoe, and when the marriage license clerk in the next county asked her age, she was to answer truthfully that she was “over sixteen.” John and Elizabeth were married under the last name Perkins to give them a head start over Lum’s shotgun. To the day she died Mo Mo Monk worried that all her children were bastards.

She needn’t have worried so hard, because it turned out marriage was a pretty flexible concept in her family. Come to find out that her own mama, Laura, wasn’t really married to Lum, who wasn’t really her daddy. That was such a relief, she later said within earshot of my cousin, because of all the nasty things Lum did with her.

Mo Mo was only two when Lum showed up in Choctaw County, Alabama, with big blue eyes full of mischief and stole her mama’s heart away. Laura ran off to Mississippi with Lum and her two youngest girls, leaving behind three boys, another girl, and their bewildered father. Lil’ Bet became the oldest of a new passel of children, almost all of them born with those same mischievous blue eyes.

Folks said Laura was part Indian, because of her high cheekbones, dark hair, and gray eyes, but then anybody living in Choctaw County was bound to have some Indian blood somewhere. Laura and Lum did eventually get married, but only when Laura was in her sixties and needed to claim his Social Security. He left her six months after, and she died alone in a rooming house in Natchez in 1961. She was buried in an unmarked grave. But Laura’s passion brought Mo Mo to Mississippi, which made my father a Monk, and from Laura’s lust I was surely made.

Lil’ Bet always worried her sons would grow up to be bank robbers. In the 1930s, bank robbers were the Robin Hoods of their day, stealing money from the rich bankers who had taken everybody’s land. Ol’ Lige, Lil’ Bet’s father-in-law, had a solution to avoid foreclosure: he reasoned that if you didn’t own anything in the first place, the bank could never take it away from you. Lige had a fascination with Jesse James and even claimed he was related to the famous outlaw. Lige named all his grandchildren—my father, the oldest, was named William Elige after him—but when he tried to name my uncle after Jesse James, Mo Mo drew the line. She left Uncle Jesse’s middle name blank on the birth certificate, and she always called him “Jesse Lee.”

As a boy, Jesse often helped out at the country store owned by his family’s landlord, Mr. Hearn. One day when he was about ten, Jesse came home with bulging pockets and sneaked into the broken-down barn out back, where an old Model T was parked. After stuffing most of his stash into the Ford’s wheel well, Jesse crammed a banana into his mouth.

“Jesse Lee,” shrieked my grandmother from the back porch, “where’d you get them bananas?”

“I bought ’em at Hearn’s store, Mama,” he mumbled with a mouth full of mashed bananas. But he knew better than to look her in the face and tell a lie.

“Naw, Jesse Lee, you stole them bananas!” And with that, Mo Mo grabbed her husband’s razor strap and sent little Jesse dancing back down the two miles to Hearn’s store.

“Aw now, Miz Monk,” the kindly old man said when they arrived, “you won’t let Jesse take any pay from me. Why don’t you just let him have those bananas?”

“Mr. Hearn,” Mo Mo said, “today bananas—tomorrow banks.”

John Monk may not have had a pot to piss in, but you were welcome to whatever he had. John was a bit of an orphan, since his mother, Mary, died when he was little, and he had grown up in a house full of half-brothers and sisters. You might sleep on a pallet on the floor and eat nothing but coffee and biscuits, but you always had a place to stay at whatever ramshackle house he was renting.

My daddy, William Monk, had a dream to own his own land and build himself a house that was free from the parade of kinfolks who always depended on my grandfather’s hospitality. His other dream was to go north to Alaska. He loved reading Jack London stories about the Yukon and the call of the wild. But something got in the way of that dream—a striking beauty with dark brown eyes, raven locks, and a luscious round body that made loving easy.

Like Juliet, my mother saw her Romeo from a balcony, and she swore to the nursing school classmate beside her that someday she would marry that boy. When William told her on their first date that he was going to Alaska, she liked his ambition right away. None of the other Mississippi boys she dated knew where they were going.

My mother, Betty Ruth, was in nursing school because of her mother’s dream, not her own. Maggie Humphreys had always wanted to be a nurse, but her daddy wouldn’t let her. Mason Humphreys was a good farmer who made enough money to buy himself a new International Harvester pickup every few years, but he berated his wife about the cost of sugar in the iced tea. He refused to pay for Maggie’s nursing training, even though his own sister was a nurse. “Nurses are whores,” he said, and that was the end of it. Or so he thought.

Maggie always said her father just wanted to keep her on his farm, working and with no pay. Mason never forgave Maggie for being the twin who lived, instead of the son he buried a few weeks after they were born. Nothing she did would ever count. When he died, he left his favored daughter and her sons $50,000 each, in 1962 dollars, but Maggie didn’t get a shovelful of dirt.

Her high school photograph reveals an expression of pride in Maggie’s face and a beauty I never imagined had existed. She had graduated from Red Lick High School, a rare feat for a Mississippi woman in 1934. To her, education was everything.

Maggie was big-boned, as they say in the South, not a delicate flower of maidenhood. So she was expected to tote like a man and work like a man and make the man’s dinner and clean his house. No courting young beaus with moonlight and magnolias for her.

Maggie had one boyfriend she really loved, but her daddy ran him off and he stayed gone. My granddaddy, Jack Smith, wouldn’t be run off. Jack wasn’t afraid to take Mason’s daughter without his approval, and they eloped with the help of cousins and her grandmother’s wedding dress. Then Maggie traded an overbearing father for an overbearing mother-in-law.

As a young man working on a road crew, Jack almost burned to death because someone sloshed gasoline on a fire he leapt over to win a bet. He spent six months in the charity hospital in Natchez, and his mama never would let him go after that.

Jack turned out to be not much help in supporting his family. He was never one for a steady job. When he hurt his back once and Maggie said, “Don’t worry, sweetheart, we’ll make do somehow,” folks say Jack took Maggie a mite too serious. He was a gambler and he had already called Mason’s bluff for Maggie’s hand. The rest would be up to her. She raised three kids and sent them to school by selling vegetables from her garden, and a few cows now and then, all on her mother-in-law’s land. Maggie would fuss that Jack spent too much time at his mama’s house, and the more she fussed the more Jack stayed away, so Maggie spent many nights alone in the old iron bed in the shack that Jack built for her.

That man was a jack-of-all-trades, for sure, and he could do just about any job until he got tired of it. Carpentry, blacksmithing, doctoring animals, harvesting pine wood, making cane syrup—he’d help anybody out who asked him, except Maggie.

Jack Smith was the darkest white man in Jefferson County, with skin toned like the tobacco he smoked and the coffee beans he roasted. But it wasn’t Choctaw that gave him his melanin, as I discovered later in DNA tests. And when I look in the mirror, his dark eyes stare back at me.

The photograph I have from that time shows Jack with his dark arm draped casually around Maggie, her pale round face and blue eyes overcast with gloom and despair, while three children crowd into the picture frame, the youngest hiding between her legs. But there is a gentleness in Jack’s face, and a genuine affection in his arm around her that lets you know he must really have loved Maggie, even though he could never satisfy her.

The folks around Blue Hill loved Jack with a purple passion. He was always there whenever they needed him. They loved him all right, but they seldom paid him, and Jack never asked. He was as proud as Maggie in his own way. When Jack died of a heart attack at age fifty-four, leaving Maggie a penniless widow at forty-five, with no Social Security because he hadn’t held a regular job, she had to borrow five hundred dollars from the bank to bury him. But Jack’s funeral cortege was the longest anybody could remember, with cars stretched out for miles and miles between Port Gibson and Fayette.

After Maggie got married, she dreamed of owning her own land and not being beholden to anyone. One summer, she convinced Jack to move their young family to Mobile, Alabama, where they would stay with her aunt, so that Jack could work as a welder in the shipyards, and they could save money for their own place. They had two small children and a third kicking in Maggie’s belly. Being heavy with child in the Gulf Coast’s heat and humidity is any southern woman’s definition of pure misery.

One day in Mobile, Maggie heard a commotion in the shed behind the house where they were staying. She heard the men’s voices, and then the roaring and the shouting, and she knew that with every roll of those dice her dream of buying her own land grew fainter and fainter. Her blood boiled, and she picked up a two-by-four and headed for the shed. A tall, big-boned woman, she loomed in the doorway of the shed, six months pregnant and spitting fire. Like an Old Testament prophet, she raised the two-by-four up over her head and roared: “If y’all don’t get the hell outta of here, I’m gonna kill ever’ last one of ya!”

“Jack,” the men cried in surprise, “take hold of your wife!”

But Jack was a realist. “Ya better get going,” he replied in his laconic way, “’cause she’s liable to do just that.”

After that summer, the pictures of Maggie never looked the same. The fire in her eyes had died to smoldering embers, and she grew fat on her disappointments.

Betty Ruth, my mother, weighed two hundred pounds the summer after her eighteenth birthday. In a world with few pleasures, her grandmother’s biscuits with homemade cane syrup and bacon were treasured delights. Better than cold butter beans and cornbread at her own home. Like her daddy, she spent more time with his mama than helping her own. The doctor said she had to get down to one hundred ninety if she wanted to go to nursing school. Eventually, she lost down to one hundred seventy-five pounds.

She had an air of dark mystery about her that fascinated men. My father, William, saw it and quickly worked to claim it for his own. Betty Ruth was impressed with his ambition, though he might have had more competition when she left for a semester in New Orleans as part of her schooling. But William saw that coming and convinced her to marry him secretly before she left.

“I never knew Daddy was so insecure,” I said when she finally told me that story. The father I knew was full of arrogance and bluster that I could never see behind.

“Maybe we were both insecure,” my mother said flatly. “I was glad I was married once I went to New Orleans,” she added. “There was this doctor there who always wanted to talk to me, and if I wasn’t married, I wouldn’t have known what to do.”

In New Orleans, she found out she was pregnant with me, and she sent word to her parents to bring her back to their shack on Blue Hill in Mississippi, away from the city of sin. A girl couldn’t be married, much less pregnant, when training with the Sisters of Mercy. But being big-boned, like her mother, I asked her much later if she could have hidden her pregnancy for three more months and finished her degree?

“I was going to be Mrs. William E. Monk, and what good would a nursing degree have been?” she asked. “I would never have used it.” But she did wind up working as a practical nurse in order to send me to a one-room church school to avoid integration. Little did she know that the “one drop rule” would have applied to her. And to me. DNA testing revealed that some of her daddy’s ancestors were African.

The house my father built was never finished. He thought it was all he could afford. It was one of those do-it-yourself specials where a construction company built the outside shell of a house and you finished the inside yourself. It took me a long time to appreciate what my father had tried to accomplish in that house, however dilapidated it became. It was his attempt to create a life not subject to landlords and alcoholism and failure.

The outside, folks say, was quite beautiful at one time. It was made from cypress, an expensive wood that didn’t rot, and turned from rosy pink to a weathered grey. The house was a small, contemporary board-and-batten style, with a modish railing on the porch that placed it firmly in the early 1960s. The inside was bare studs, and he insisted on finishing the walls board by board, solid pine, no fake paneling.

Years passed, and by the time I was seven, my daddy nailed some plywood panels halfway up the walls in my room so my brothers couldn’t peek in. But he could see. When I turned twelve, he finally finished the walls in my room, but not the closet between my parents’ bedroom and mine. I heard everything that went on in there—the crying, the pleading, the angry yelling, the threats.

The house was built on a cement block foundation, raised off the ground. The men on the building crew would drink beer at their breaks and toss the empty cans under the foundation, upsetting my Baptist mother. “At least your daddy doesn’t drink,” she always said, even when bruises appeared on her body. But the house wasn’t built square, and after a few years the modern porch railing began to collapse, and the walls started to sag. Even the cypress rotted through in some places.

After fifteen years, the house was paid for; the mortgage payment was $52 a month. My mother saved the last cancelled check and stuck it in the unfinished hall where we all could see it, behind some electrical wiring along one stud. She had written across the check: “our dream come true.”

I was never interested in genealogy growing up. That was the domain of blue-haired old ladies who thought they were better than I was. Besides, nobody knew who came before Ol’ Lige in my father’s line, and few of them could read or write, so what was there to find out? What was there that I wanted to find out? Nobody in my family had ever been where I was going. I was the first in my father’s family to graduate from high school, and the first in my mother’s family to attend college.

Yet my family connections are what got me into Harvard Law School. Right before I applied, an important Supreme Court ruling on affirmative action stated that Harvard, in particular, was looking for students with an interesting background. Well, my family is nothing if not interesting! I thought. I had good grades and test scores, but so did the other 7,500 people who applied for the 540 open slots. The first sentence of my admission essay sealed the deal: My ancestors comprise a long line of Mississippi mule thieves and sharecroppers.

When I told my beloved Paw Paw, John Monk, that I had been admitted to Harvard Law School, he smiled widely and said, “That’s good, honey.” Then he asked, “Where’s Harvard, baby—is that in Tennessee?” To an illiterate man who seldom drove outside the state of Mississippi, the farthest place he could imagine was Tennessee.

Why didn’t my father hook up the hot water heater? That was the question I was aching to ask him on his deathbed but never did. He lay dying in the hospital for almost two months—good protoplasm kept him alive, the doctors said—despite wasting from the alcoholism that befell him later in life and the fall at work that finally did him in.

For all the years that I lived in my father’s house, I had to heat water on the gas stove and carry it to the bathroom in the back of the house to take a bath. The house was unfinished in manifold ways, but the way that mattered most to me day to day was no hot water. Washing the dishes—boil the water; washing yourself—boil the water. The hot water heater was there, sitting in its unfinished stall, and I just always assumed it was broken and we were too poor to have it fixed. Then one weekend I returned home from college and poof! we had hot water. It was that same damn hot water heater that had sat there all those years—all those baths taken, all those dishes washed—now working fine. It just had to be connected.

My daddy never made it to Alaska, though the recycled beer cans alone could have paid his way. He stored them all in my old room, piled high to the ceiling—a stale, sweet smell coming from the last drops of beer in each can. The roaches had a field day.

At his funeral, I learned a lot of things I didn’t know about my daddy. There had been only one job, later in his life, that he actually enjoyed: being a foreman on the restoration of a Civil War gunboat for the National Park Service. He used his mechanical skill, his love of history, and his inventiveness to bring that ship back to life, and when that project ended, so did whatever dreams he had left for himself. I met his supervisor at the service and said how sad I was there hadn’t been another job like that for my father. “Oh, but there was,” the supervisor told me. “I was going to send him for training in Denver, and then he could have gone anywhere in the Park Service, but he turned me down.”

Then Uncle Jesse, who spent those last years with my daddy, told me something else: when my mother lost her mind, the doctors advised my father to commit her to Whitfield, the state mental institution, because her case was hopeless. “I just couldn’t do it, Jesse,” he said. But that’s also when he took up drinking beer.

When my daddy was growing up, John, the kindly grandfather I loved, was a chronic drunk, and he abandoned the family every time Lil’ Bet got pregnant. She almost died from a hysterectomy when my daddy was twelve, and he had to take care of three little brothers. When my daddy became a father himself, every bill was paid on time, and no matter what, he never left. He never, ever left.

Do not be surprised, when you go searching for your ancestors, if they find you first. Turns out Ol’ Lige, my great-grandfather, had a secret—one he thought he had taken to his grave. I found it out just a few days after I subscribed to an online database of family history records. Lige was nowhere to be found—so I looked for his first wife, my grandfather’s mother, Mary Monk. We were told she had died of pellagra—a disease of malnutrition that ran rampant among African Americans and poor whites—not long after John was born. There were multiple entries for a Mary Monk in Mississippi, but I knew right away which one was mine: Mary Monk, inmate, 1920 census; Mary Monk, patient, 1930 census; Mary Monk, death certificate, 1969. All the online census and death records were from the state mental hospital, now at Whitfield. She lived there almost fifty years, less than an hour from my house, and we never knew she existed. She lived longer in one place than anybody else in my daddy’s family.

It took several court proceedings for me to find out the truth, because Mary’s medical records were sealed under Mississippi law. Mary and her four-year-old son (John, my grandfather) had been admitted to the state charity hospital in Vicksburg in 1919, at the height of Mississippi’s pellagra epidemic. John was discharged, but Mary was committed to the insane asylum. According to the doctors’ notes, she thought Lige had been killed, but Lige had left her there and never looked back. She said she had a miscarriage, and a high fever, and then they put her in jail. She said that German submarines controlled her mind, and that she had two sons—one was an apostle (my grandfather John?), and the other was Jesse James. I’m still looking for Jesse James.

When I found Mary’s death certificate, my family hoped to move her body back to my grandfather’s burial plot, the only piece of real estate he ever owned. But I discovered that under Mississippi law at the time, the unclaimed bodies of mental patients were sent to the state medical school to be dissected. None of her family knew to claim her, because nobody knew she was there. The same law required that such remains, after dissection, were to be “decently interred.” But when I inquired at the medical school, an anatomy professor said no records existed before 1972, when the law changed. Most likely she was cremated, he said, and the ashes thrown out with the trash.

Linda R. Monk, J.D., is a constitutional scholar and author of The Bill of Rights: A User’s Guide. She has served as a visiting scholar at the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia and UNC’s Center for the Study of the American South. She twice won the American Bar Association’s Silver Gavel Award, its highest honor for media fostering public understanding of the law. Currently she is working on a memoir: White Trash Roots: From Jamestown to Harvard and Back Again.

Header image: Erosion near Jackson, Mississippi, by Walker Evans, March 1936. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.