"The South is a ghost, a ghost is a lie . . . "

1.

When I was five and my brother Jason was three, we lived in an old white farmhouse near the James River in Varina, Virginia. I was too young to believe in the idea of ghosts; otherwise, I’m sure I would have been convinced I was seeing them in every dusk-dim corner of the property—by the old Steinway at the foot of creaking wooden stairs, in the shadows of tall door frames, along the yellow fields of broomsedge stretching up to the giant robot army of power lines marching forever toward the big city of Richmond.

2.

“I don’t remember any ghosts,” my brother offers at a family dinner in 2019. Grown now, Jason is a filmmaker and I am a songwriter, and our returns home are rare and often loud with conversations about family and memory. And, inevitably, also politics.

“You remember that place? You were so young.” I find it hard to believe that my brother remembers the white house at all. “What years were we even there?” I ask our mother.

“I was so afraid you all would wander back under the power lines,” my mother says, bringing her hand to her head and evading the specifics of the question, consumed with guilt. (This is a woman who has never owned a microwave for fear of what radiation may or may not do to the human body. When questioned on this matter, she’ll shush and respond with “Those experts . . . they’re just like doctors, Skylar. They don’t know anything. They’re only practicing medicine.”) She waves her hand and then shakes her head, lost in thought, and stares at my brother and me as if her original decision to bring us into this world may have been the wrong one. “The landlord had all sorts of tests done where the county came out and measured the magnetic field on the land . . . ”

“It was ’92 or ’94? Something like that. Bill Clinton was president,” Jason says.

I’m amazed. “How do you remember that?”

“Remember that time I ate pokeberries?” Jason says. My mother moans. “And I had to drink ipecac syrup.”

“Oh, right! Isn’t that stuff, like, illegal now?” I ask.

“We called the poison control center and they told us to!” my mother defends. Jason pats her on the head.

“It makes you get sick so you vomit up whatever bad thing you ate,” Jason answers. “So I ate the pokeberries, and then when I got sick, I threw up on a Time magazine with Bill Clinton’s face on the cover of it. That’s how I remember he was president.”

3.

Pokeweed: good for the songbird, the cedar waxwing, or mourning dove, deadly to mammals when ingested. The shrub grew in the front yard, where its purple berries hung low on bright magenta stems. The leaves from young poke can actually be eaten, often served in what’s traditionally called poke salad—a dish prepared by foragers and survivors in Appalachia for centuries, because for all of its toxic properties, pokeweed is plentiful and free. Picked in early spring, before the berries come, the poison is cooked off by washing, boiling, and draining the leaves two or three times before the addition of onions and vinegar or another dressing. Culinary historian Michael W. Twitty, on his blog Afroculinaria, illuminates pokeweed as a food source “collected and sold by the enslaved community. Poke salad . . . along with other edible weeds would have been collected by women and children as they gathered resources from the wild.”

The pokeweed at the farmhouse in the 1990s was certainly wild heirloom and kin to the pokeweed that would have grown along the James River in the 1600s, at a time when Varina was littered with tobacco plantations, the first cultivated cash crop in America, worked by thousands of enslaved African people. And before Europeans ever violently settled that land, Native peoples of the Powhatan Confederacy gave pokeweed its name and applied it medicinally as a balm for cancers and rheumatism.

4.

Dolly Parton had another use for the poisonous plant: “Until I was a teenager, I used red pokeberries for lipstick and a burnt matchstick for eyeliner. I used honeysuckle for perfume.”

Dolly Parton is a feminist icon, but was especially revered in our house. I remember my mother telling me, “She writes her own songs,” which was a big thing to note since composers earned highest praise among my musical family, and the ones in my children’s classical music books appeared as paintings of men in powdered wigs. As I began to grow, always singing and writing in the fields by that farmhouse, my mother held up examples of women players, writers, and singers. She asserted that, as a singer, you would have the most independence if you had control over what you were singing and if you didn’t have to rely on anyone else to back you up. I’m sure too, beneath her unending and pragmatic support, was my mother’s own knowledge of how hard it is to be taken seriously as a woman. Better to stockpile secret weapons, I learned. Dolly’s sequined dresses, heaven-reaching hair, and the self-imposed silicone wall between her and the world seemed like armor—every sweet smile and self-deprecating remark read to me like a secret joke she was playing on everyone who discounted her.

I was wide-eyed about any woman out living in the big world—the big world being somewhere I saw as existing entirely away from me, merely due to temporary constraints both geographical and age-related. Most of those women I encountered in the news via magazines or on one of the two-and-a-half channels we’d get on the TV we were only allowed to watch on weekends. The women in the news loomed large with instructions about how to carry oneself, and how you might expect the big world to receive you. It was in this education that, starting with my brother’s run-in with pokeberries and Bill Clinton, the Lewinsky scandal now surfaces to me as one of my earliest political memories. The nonstop coverage I absorbed about Monica and her blue dress, and bad things done by the man I had heard the adults say was the good guy, left a layer of impressions, like watercolor strokes, undelineated but marked, and their message clear: Women were wife or mistress, while men used the clothes you wore against you and, at the end of the day, remained in power.

5.

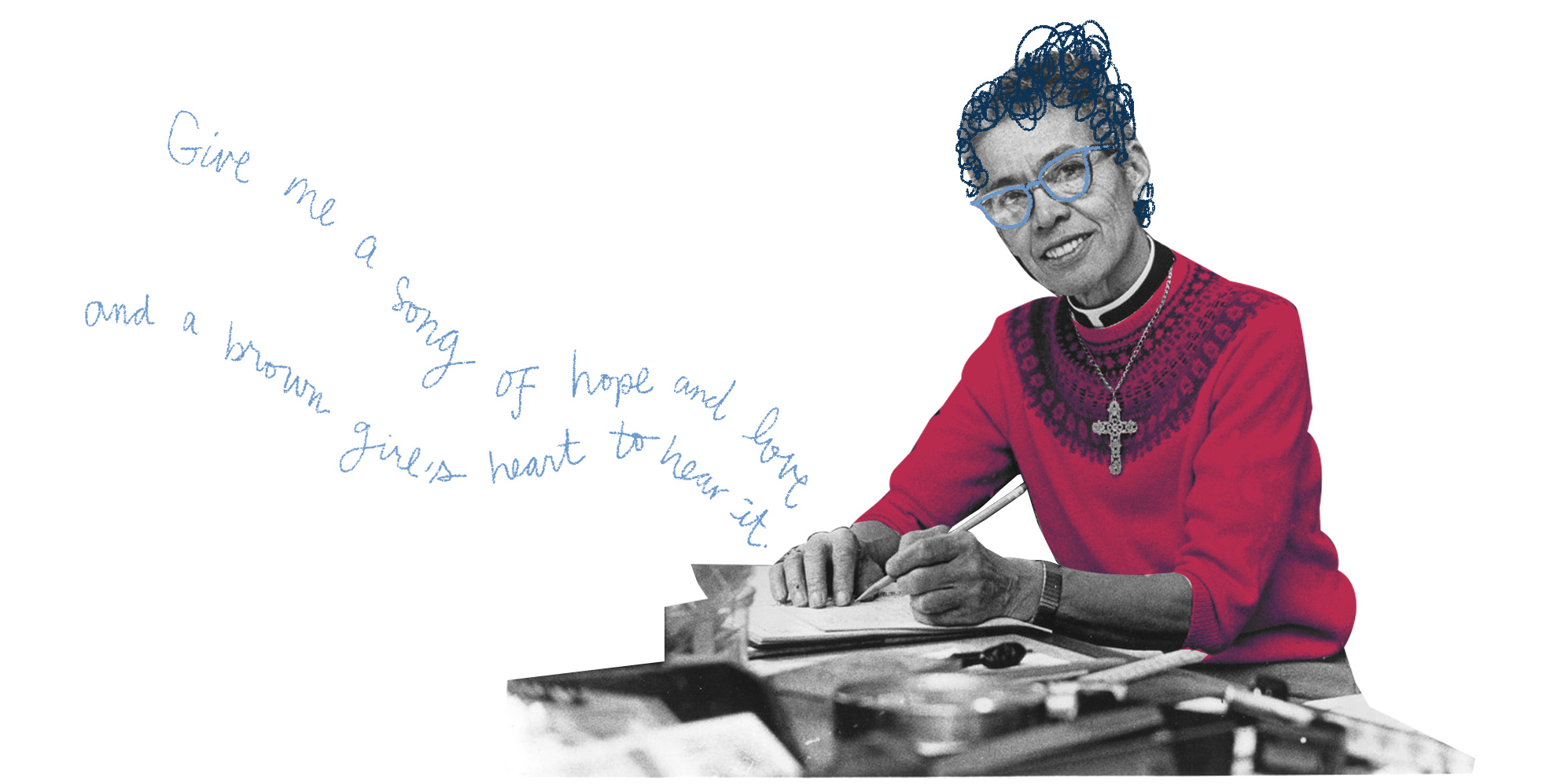

Through this sensationalist filter of the news, of course, many heroes slipped past my young consciousness. For instance, the legacy and influence of the brilliant Dr. Pauli Murray evaded me until I moved as an adult to the place she grew up, Durham, North Carolina, and saw bright murals painted of her on buildings. Rainbow portraits bannered across the city from an elementary school, to a co-op, to a busy intersection near her home were history lessons free and accessible to the public. Dr. Murray, an accomplished author, activist, and lawyer, was a gender-nonconforming black feminist who co-founded the National Organization for Women, became the first African American woman to be ordained as an Episcopal priest, and advanced visionary arguments on the intersection of gender and race, such as Jane Crow and the Law. Murray’s arguments (for years, it is worth noting, without anyone crediting her) also served as the foundation for major cases decided by the Supreme Court, namely, segregation in Brown v. Board of Education, argued by Thurgood Marshall and Spottswood Robinson III, and sex discrimination in Reed v. Reed, argued by Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

In addition to being influential, determined, and a paragon of early intersectional feminism, Dr. Murray was a poet. In her poem “Dark Testament,” she writes,

Give me a song of hope

and a world where I can sing it.

The two lines, which read like a prayer, suggest that we have not yet devised a world in which her hopes can find expression. The poem ends on a clarification for whom specifically it was she dreamed:

Give me a song of hope and love

and a brown girl’s heart to hear it.

Pauli Murray’s audacity to envision a world that would allow all of her to thrive, a world she worked to build as a lawyer and an artist, brings to mind the poet Mary Oliver’s essay “Of Power and Time.” In it, she illuminates how creativity serves social change:

In creative work—creative work of all kinds—those who are the world’s working artists are not trying to help the world go around, but forward. Which is something altogether different from the ordinary. Such work does not refute the ordinary. It is, simply, something else. Its labor requires a different outlook—a different set of priorities.

6.

Fast forward to the 2018 Supreme Court on which the extraordinary Ruth Bader Ginsburg sits. Enthusiastic videos endorsing Brett Kavanaugh’s fraught appointment to the Supreme Court are running, starring Hillbilly Elegy author J. D. Vance, who took time out of being “lucky enough to live the American Dream” to pitch for his fratty former mentor. The Kavanaugh confirmation hearings captivated twenty million viewers—and traumatized and enraged perhaps many more—and Black Twitter cycled mentions of Anita Hill back into public conversation for an unknowing generation that was not taught her name.

Soon after, America decided it needed, simply, something else, giving women of color historic victories in Congress: the first two Native American women, Deb Haaland and Sharice Davids; the youngest African American woman, Lauren Underwood; the first two Muslim women, Rashida Tlaib and Ilhan Omar; in the South, Texas elected its first Latina representatives, Veronica Escobar and Sylvia Garcia; and in the Bronx, the youngest person to be sworn into Congress, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

7.

Those exciting 2018 midterm elections signaled a rejection of corporate influence and a reclamation of proud progressive values. Ocasio-Cortez, for instance, who ousted a more centrist Democrat, championed the Green New Deal, a program to address climate change and economic inequality. Previously hollow mantras of “create jobs” had a new and deeper resonance when endorsed by someone who a year before her election was working as a bartender. While a wealthy establishment deems this work history unbecoming to a politician, young people see it as a badge of honor. They see their experiences reflected in Ocasio-Cortez’s financial struggles more than in the cadre of spray-tanned and cufflinked incumbents currently serving in the House.

These women speak to another American Dream—not Kavanaugh’s journey from prep school to ivy to higher and then highest court, or Vance’s exploitative rung-climbing rags to riches “luck,” or even Dolly’s down-home business-savvy-cum-philanthropic stardom, but a more equitable trajectory coursing through the symbol of the new Congress: that a person’s humble means should not hinder their ability to have a say in governance, that any woman should be able to rule herself, and that racial equality in representation is necessary to redress the original violences of this country’s founding.

8.

Before the 2016 presidential election, I was touring the country and singing with Eric Bachmann, brilliant son of North Carolina, and his band. The schedule: leave the hotel at 9:00 a.m., stop for breakfast if you’re lucky, drive two vans five or however many hours, load in, check out the green room, plug your phone in, soundcheck, eat dinner, put on a dress and lipstick, climb the stage and sing . . .

The South is a ghost, a ghost is a lie . . .

Then do it all over again the next day. The music is beautiful and the company lovely and so the road is good. It gives you a lot of time to think. Sometimes there are a few hours here or there, and whatever you do is based on the time you have. Before we leave for the Northeast, I find a little while in Durham’s best low-lit bar, Arcana, and get a tarot reading. Green lamps make everyone undinal. The unsmiling reader is draped in beads and wears round glasses and a quarter moon–shaped ring at their septum. I sip the Young Hierophant—bourbon, cardamom, and citrus peel. As is the general way of southerners, we make small talk with gravitas.

“Is this your hometown?” I ask.

“No, I’m from Savannah.”

“What brought you here?”

“I had to leave Savannah. She’s stuck in the past.” I assume they mean politically, but they clarify. “Too many ghosts in Savannah. Too much violent unatoned-for history. Too many souls there against their will. Savannah loves her ghosts, she’s obsessed with them, she’s defined by them, and so she can’t let them go and so she can’t move forward.”

Later, on the road, the memory of the cards I drew were lost, but the perpetual haunt of the southern past I understood viscerally, though maybe not so materially. If the South is a ghost, and a ghost is a lie, does it exist? If we can’t see something but as a society we all feel its weight, can we deny its presence and impact on our decisions, or the ways it has invisibly strangled or tangibly served us? Is the South a moral reckoning ground for the country, its ghosts the old spirits of our nation’s conscience?

9.

When I pose these questions to my brother a few days later, he says, “You sound like you’re—” His voice breaks up, a bad connection. “. . . something.”

“Onto something?”

“No, I said you sound like you’re on something. Are you okay? How long are you out for?” I gaze out at the nearby wharf. I am not sure if what I am looking at is Rhode Island. Somewhere the rest of the band is eating lobster rolls from a famed hole-in-the-wall with big windows and a striped blue awning.

“Two more weeks.”

“Come to L.A. People are going to vote for Jill Stein here.”

I can feel the Southern California sun crackling through the cracked screen of my iPhone, like several hundred sun emojis.

10.

Young people–those who will inherit the ravages of climate change, people I know in the Southeast who walked door-to-door in a mild October and made phone calls for Barack Obama in the first presidential election they were old enough to vote in—some of them didn’t vote for president in 2016. Perhaps disillusioned, they don’t see themselves within the power structures that exist. Perhaps internalized misogyny runs very deep. Perhaps they are afraid of the continuous war we have been in since most of us have been alive. Perhaps they felt let down by the inability of a progressive party to actually uphold progressive ideals when faced with hard choices and big money. Perhaps the still very acceptable racism and sexism in our country that crosses party lines has gotten them down; perhaps when it comes to wealth, those governing on the right and the left look the same to them; perhaps they know the structural inequality of America goes deeper than presidential administration; perhaps they feel the weight of their country’s history and don’t want to participate in its legacies. Perhaps they truly feel their vote does not count in a state whose congressional maps are so gerrymandered that the U.S. Supreme Court has declared them unconstitutional multiple times and newspapers ran the headlines “North Carolina No Longer a Democracy.” Perhaps it’s because the NCGOP denied Medicaid expansion in the wake of the Affordable Care Act and passed anti-LGBTQ legislation into law with HB2. Undoubtedly, it is hard to have faith in an institution that is actively trying to disenfranchise you, even if that very fact is an argument for participation.

And yet, here, in the allegedly “backward” South, thrive the most politically motivated people that I have ever met: lawyers representing asylum seekers one painstaking case at a time; farmers of small farms in a changing climate adjusting pesticide-less growing practices and sustainability; anarchists organizing airdrops and driving trucks of supplies to Lumberton so that they might be distributed to people stranded by the devastation of Hurricane Florence; activists removing white supremacist statues in acts of civil disobedience; feminist small business owners paying a living wage to their employees even though they are not legally required to; organizers hosting weekly prison letter writing campaigns as they work toward prison abolition. Workers self organizing and fighting against oppression for dignity and empowerment on their terms is a common story in the long history of resistance in the South. People who, daily, often in spite of the law, dedicate their lives and work to change and arguably have more direct effect on restructuring inequality than someone who just checks a box in November. Voting for president, surely, is civic power at best, and harm reduction at least—but it’s also far from the only place where southerners define themselves or do their political work.

11.

Here in 2020, looking for a sign, guitars in black cases stacked behind me, I thumb through James Baldwin as we drive through Richmond on tour: “It takes a long time to realize that there is a past . . . It takes a long time to understand anything at all about what we call the past—and begin to be liberated from it.” This stretch of I-95 marks the same drive that my mother would make from time to time when, in the spirit of learning, she would take me out of school to attend protests at the state capitol. Emmylou on the radio, past soybean fields and former plantations in Varina to the General Assembly Building in Richmond, we would inevitably cross Monument Avenue, where city blocks of Confederate statues interrupted traffic flow and striated sunlight warmed me through the backseat window of our white truck.

Now though, the drive opens on a new monument: Kehinde Wiley’s recently erected statue Rumors of War, a re-imagining of the hero-on-horse aesthetic, except this bronze sculpture stars a black man in a hooded sweatshirt and Nikes, speaking back to the old stones of the Confederacy behind him.

12.

Time shifts, pokeweed grows on, ghosts gather in the doorways. The poison in our front yard was there before we were, but it is ours to reckon with, and it is ours to survive. What we have inherited and its proximity to us—in our food, our lipstick, our voting cycles, our music, our writing, our identities—calls on us to manifest that transcendent promise of politics, to enact in reality the soaring myths by which an Icarian America has defined itself and fallen short. We must be those artists with the dreamer’s work ethic trying to help the world go forward, through the past and future at once.

Skylar Gudasz is a musician, actress, and songwriter currently living in Durham, NC. She is the composer and performer of a critically acclaimed debut album Oleander. Her forthcoming LP, Cinema, will be released in April 2020.