The house shelters daydreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace. —Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

In the middle of a childhood marred by hard labor and an abusive father, Eddie Owens Martin got out. While Eddie had already been sharecropping cotton with his family for years, he was only fourteen years old when he took up sex work to support his travel from Glen Alta, Georgia, to New York City in 1922. In addition to the hardships there, life in Glen Alta felt small to Eddie. “If I wasn’t workin’, I was sleepin,’ ‘cause that’s all there was to do,” he said in an interview with author Tom Patterson, who collected their conversations into a journey through Eddie’s rambling life.1 After hearing about New York from a teenage cousin who had been around the block, Eddie became determined to carve out a new path leading away from the drudgery of hard labor and the cruelty of his father. “The night after he left … I knelt and faced to the full moon that was out that night, and I prayed to God to make me different from anyone else in the world. And by God, I think I succeeded in that prayer.”2

Eddie made it to New York and back again, bringing home his exposure to both subterranean and institutionally promoted cultures he encountered at the city’s nightclubs, drag balls, theaters, and museums. These experiences collided and coalesced at the artist-built environment he eventually created—Pasaquan, the kaleidoscopic paint and concrete compound that was an outward extension of Eddie’s inner world. It was his home and his place of business, a site of play and of security. And it is just one of many such places—manifestations of overwhelming, life-consuming creativity in the American South—crafted as sites of refuge, joy, and worship within communities that sometimes met their makers with exclusion, derision, or even violence.

While materially quite diverse and created with unique intentions, these artist-constructed places operated both as intimate realms of self-expression and open lines of communication with the world at large, uniquely straddling the line between private and public. Home-centered projects like Pasaquan, and, as I will later discuss, Pearl Fryar’s Topiary Garden and the Saint Paul Spiritual Holy Temple, offered their makers both the physical space (an asset more readily available to rural folks) and the temporal space to create, recreate, uncreate, and create again over decades. Location and process are integral to the significance of these artworks. Leslie Umberger applies religious historian Mircea Eliade’s phrase “the heart of the real” to describe environments like these, each of which is “a venerated place, a place that activates a personal harmony or spiritual connection.” Umberger continues: “The secret of sanctity lies not simply in the locale nor in the believer, but in a complex relationship between the two.”3 Perhaps most importantly, these are sites of power—the power to put down roots, to fully inhabit a space, and to make it one’s own.

Eddie’s world expanded rapidly once he arrived in New York. Knowing he “had to make a buck to survive,” he continued performing sex work and joined a vibrant community that exposed him to “actors, actresses, artists, dancers … thieves, goofers, gangsters, politicians, pimps, whores—I met ’em all.” The potential dangers of his vocation required Eddie to develop a keen ability to read the people around him. “You had to be careful, and really you had to be psychic just to survive, man. You had to know what was goin’ on in front of you, behind you, and to both sides of you. You had to be hip to it all.”4

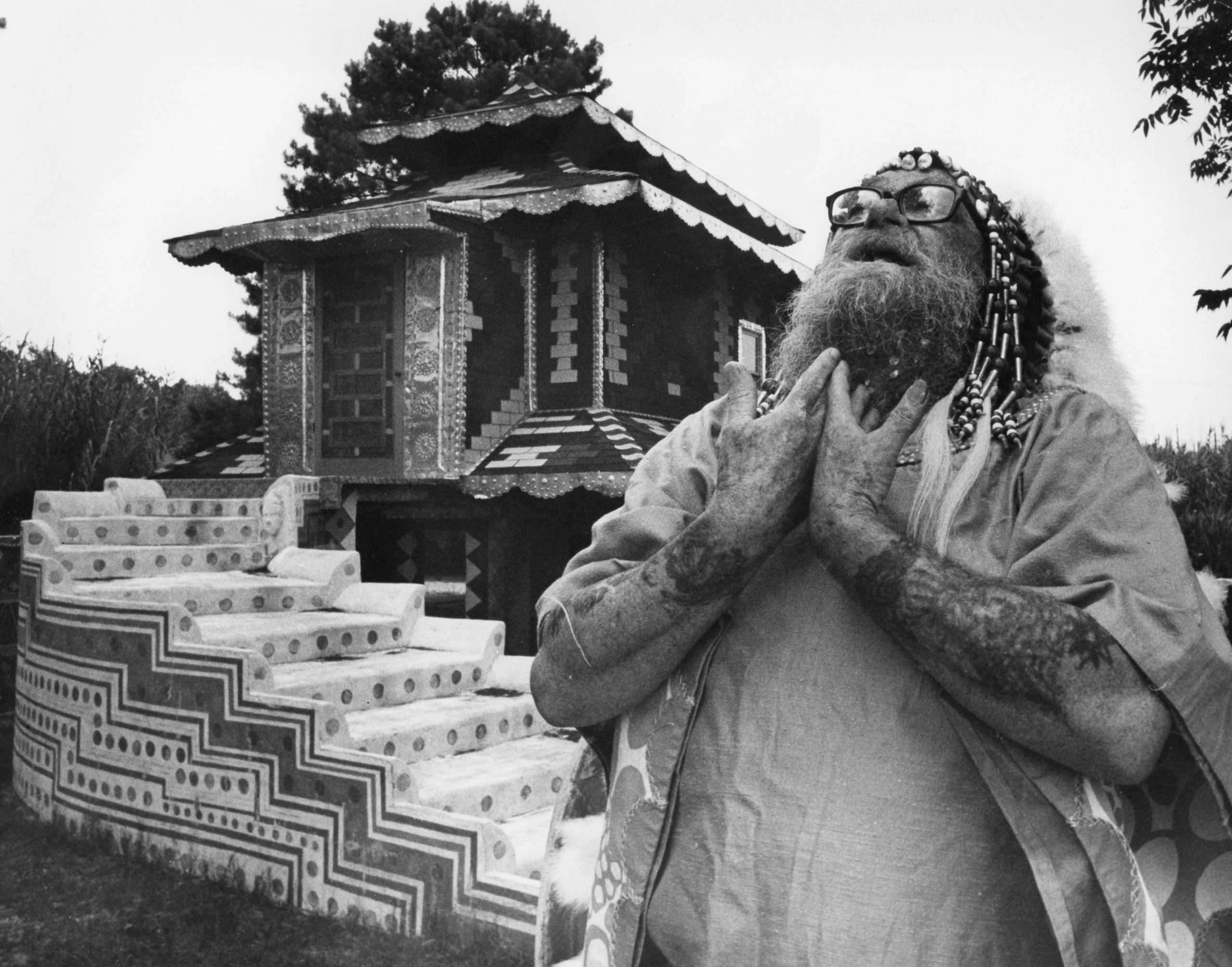

After his father died in 1928, Eddie began making yearly trips to Georgia to visit his mother. She had moved to a farmhouse on a large property in nearby Buena Vista—land that eventually became his. It was during one of these trips that Eddie found Pasaquoyanism; or, rather, it found him. In 1935, he fell desperately ill, and as he skated on the edge of consciousness, he was visited by a “great big character sittin’ there like some kinda god … when I saw him I knew I had reached the end of my spiritual journey.” This visiting entity offered him the option to follow its spirit, and he did. “It was then that I decided to be myself, regardless of the cost, regardless of the ostracism … I listened to that inner voice, and I recovered.” During the voice’s second visit, it said to Eddie, “You’re gonna be the start of something new, and you’ll call yourself ‘Saint EOM,’ and you’ll be a Pasaquoyan—the first one in the world.”5 According to Eddie, now St. EOM, Pasaquoyanism was concerned with “the Truth, and with nature, and the earth, and man’s lost rituals.”6 Through continued close listening to the inner voice and his study (and appropriation) of world religions and cultures, Eddie developed his newfound spirituality. Referred to as “the lost art of the hair and the beard,” he stopped cutting his hair and applied a rice paste and turban to encourage it to stand straight up as an “antenna to the spirit world.”7 Though St. EOM had been deeply embedded in New York’s colorful ballroom and jazz scenes, his new look was too eccentric for even his hustler friends, and he was essentially cast out.

St. EOM had found religion, but the drama of his life didn’t slow. He served a brief prison term in Lexington, Kentucky, for marijuana possession, then returned to New York where he worked in clubs for several years until he found a job as a fortune teller in a tearoom, a convenient place to combine his astute ability to read people with his peculiar Pasaquoyan garb. St. EOM’s years of hustling served him well in the tearoom, and with the steady income, he was able to purchase art supplies and dedicate more time to painting and drawing. He continued expanding his exposure to Indigenous cultures through frequent visits to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Natural History, acquiring influences he readily pilfered for his own artwork. He submitted his art to galleries with no luck, eventually realizing his “radical” work would never be accepted there. He had to make a place of his own.

St. EOM’s mother died in 1950, and after several years of continued trips back and forth to the property in Georgia, the inner voice pressed him to move home for good in 1957. His very first project on the secluded property was a wall drawn directly between himself and the town of Buena Vista, establishing the boundary of his spiritual nation of one. His first architectural efforts (built with the assistance of local hired hands) were experimental, and while the first wall had to be torn down, what eventually replaced it was a prismatic display of swirling mandalas and striking patterns reminiscent of Incan design, among many other cultures from around the world.8

This was just the first project of a lifetime of creating; the artwork on-site continued to grow into a critical mass of highly decorative and symbolic temples, pagodas, walls, and other structures, including a ceremonial sand pit. Perhaps occupying multiple roles—protectors and companions—the walls are populated by “sentries,” representations of Pasaquoyans from across the spectrum of race and gender. They stand guard with eternally open eyes surveying the property, many of them inspired by friends left behind in New York as well as local folks, including his mother.

In addition to fulfilling his (and the inner voice’s) urgent need to create, the spectacle may also have served other practical purposes. For one, St. EOM brought his psychic abilities home with him and built a large client base through word of mouth. The psychedelic environment helped set the tone for the mystical tearoom experience awaiting inside. Surely a man with such strength of vision could harness that power to access hidden realms of information. In fact, the site was only one component of the mythology St. EOM constructed around himself. The author of his own legends, he worked hard to convince locals of his supernatural powers over nature. When he would drive into Buena Vista, a clowder of cats would disembark from his Ford station wagon and stalk the downtown. When he was done with his business, he would whistle to signal the cat horde to join him back at the vehicle.9 He also shared photos of himself charming cobras, a rumor that lived on until a fake snake was discovered in the archives of Pasaquan, according to site director Mike McFalls. This carefully crafted mythology was at once productive for his business and intimidating to outsiders who may wish him harm. Like a brightly banded snake, the audacious colors and larger-than-life persona drew in the like-minded and curious while serving as a warning to the rest that St. EOM was not to be messed with.

With an awareness that he was living in an era simultaneously in the distant past and distant future, the creation of Pasaquan was St. EOM’s opportunity to embed himself into a self-constructed, sacred landscape—one where he could live, love, and worship as he pleased. He was the master of his own story until the very end, dying by suicide in 1986 rather than slowly succumbing to the pains of old age.

Pearl Fryar’s Topiary Garden

Like St. EOM, Pearl Fryar was also born to a sharecropping family in a rural community, albeit thirty-two years later and more than 450 miles northwest in Clinton, North Carolina. He spent his youth cropping tobacco with his family until he eventually left agriculture for manufacturing. After ten years in New York with the American National Can Company, he was ready to return to the South. He asked to be transferred to the facility in Bishopville, South Carolina, and when his request was denied, he quit. Eventually, though, the company offered Fryar the position.10 He and his wife looked for property close to Pearl’s new job when they discovered the perfect house, but the Fryars were not welcome to purchase the home due to white neighbors making the prejudicial claim that the African American family “would not keep up their yard.” Undeterred, they continued their search in a different neighborhood, eventually settling in a red brick ranch house with a sprawling lawn in front of a lush backdrop of forest.

Though he was working twelve-hour shifts at the canning facility, Fryar set to work in 1984, transforming his yard into a personal oasis.11 With no prior knowledge of topiary care and design, Fryar gathered cast off plants from a local nursery (“junk,” according to the nursery owner) and gently coaxed them into living abstract sculptures.12 Often working well into the night, his light bobbing around the property, the resulting morning miracle was a delightful spectacle for his neighbors, many of whom were able to see the property fully transformed again and again throughout the years. The Bishopville Garden Club wasted no time in the face of such artistry. In 1985, they awarded Fryar with the highly coveted “Yard of the Month.”

Fryar’s work continued to spread until there were hundreds of intricately designed trees and shrubs (primarily junipers, cypresses, hollies, balsams, firs, and pines) populating the property. He approached this work with a sophisticated sense of space and proportion, carefully considering how each piece came together to create a whole. “While I’m at work on a plant, I’m already planning how it’s going to relate to the next one. Sometimes one piece over there,” he gestures to a section of his yard, “relates to some other one way on the other side of the yard. Sometimes it don’t. I love balance, you see. I put balance in every plant. I’m not talking about symmetrical kind of balance, I’m talking about balancing a combination of shapes, or a line and a curve,” said Fryar to collector and artist advocate Bill Arnett in an interview in the late 1990s.13 Anyone who has tried so much as keeping a houseplant alive can see the physical work and sheer will required to create this three-acre Eden is shocking; however, Fryar’s intended takeaway for visitors is that they recognize the intellectual and creative labor required to manifest a place as singular as his garden. “The way to understand people is to study their culture. When I walk out there in my yard, and I do what I do, I’m showing what we can do, and what we always could do: a little thinking.”14

The living artworks come together to form a verdant, outdoor cathedral. Privy to this daily exchange between man and nature, Fryar’s wife Metra observed, “God is somewhere mixed in there.”15 The garden is down a residential street with large, open lots. It’s quiet and still. When I stopped by July 2021, the humid summer air lay thickly on the grounds, dampening sounds and slowing movement. Though Fryar is now in his eighties and no longer able to work on the site, it’s easy to imagine him moving through the space, shears in hand, carefully considering each minor branch. It’s easy to feel grace among these living things that were so well loved and so thoughtfully attended.

The Saint Paul Spiritual Holy Temple

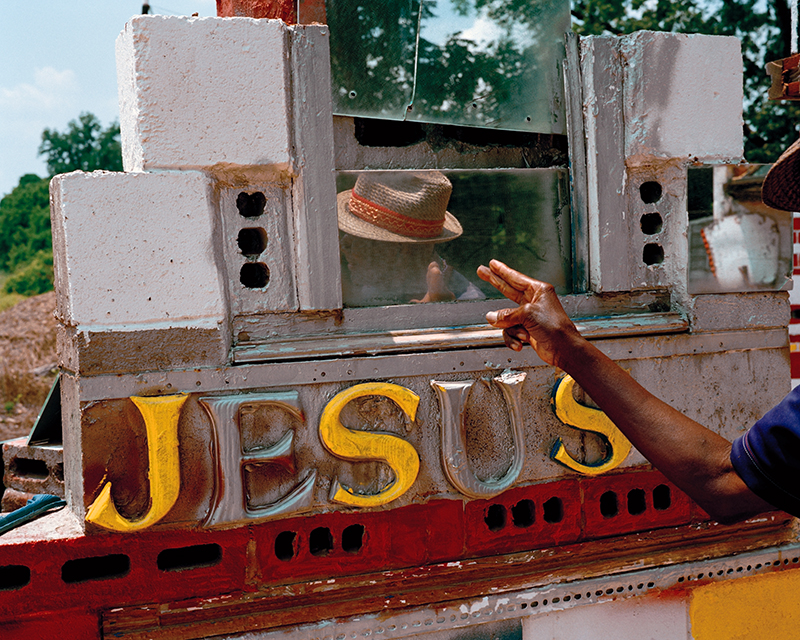

The spiritualities of selfhood and nature are deeply present at both Pasaquan and Pearl Fryar’s Garden; Washington “Doc” Harris, on the other hand, was building a church. A Black and Indigenous spiritual healer from the Mississippi Delta, Harris moved his family to the Boxtown neighborhood of South Memphis in the 1940s with the mission to create a new home for his Christian congregation and his healing practice.16 In addition to his ministry, Harris was a deeply committed Freemason. Using both biblical and Masonic imagery, he and his family created a large body of sculptural works integral to the teachings and practices of The Saint Paul Spiritual Holy Temple. This combined collection of hundreds of discrete objects form “The Degrees of God and Craftwork.” Called simply “Craftwork” by the family, the objects are astounding in their compositional breadth and craftsmanship.

The Temple occupies about two acres of rural property at the end of a mostly empty street lined by a metal fence. At one time, the gated entrance was framed by a large arch with wooden letters spelling “GOD” repeated across the facade. A compound of structures—Harris’s office, the chapel, and several homes and other outbuildings—lies immediately past the gate. Installed throughout the property are large, brightly painted wood and metal assemblages, all abstract, their significance knowable only to other Masons. The Craftwork comprises a stunning number and variety of ceremonial objects, including wooden rams and other animals embellished with patterned beads and costume jewelry, esoteric structures crafted from meticulously layered cane harvested from a canebrake near Harris’s home in the Delta, tableaus illustrated with finely appointed mannequins, silken banners lining the chapel interior, monochromatic assemblages affixed with cut-wood symbols, and much more.

Harris welcomed his congregation to the chapel for traditional Sunday church services and tended to patients in his office. Part of a robust network of spiritual doctors in the Midsouth, Harris primarily assisted his patients through counseling, of which the Craftwork played a large part. His intention to create a sacred and healing space for all who sought it went unrealized, however, shortly after he publicly shared the work of the Temple. In 1961, Harris contacted the local Memphis Press-Scimitar with an invitation to visit the Temple to view what he and his family had created and learn about the true significance of the work. In the article, Harris explains, “We have an eternal organization here. A church. Our temple is the most beautiful place in the world. All these things have a meaning. They are symbols of God.” While he saw this publicity as an opportunity to correct misunderstandings about their religious and creative practices, the unfortunate result of the piece (printed adjacent to a different article that listed the address of the site) was acute, prolonged harassment. Pejoratively deemed “Voodoo Village” and primarily referred to by that name today, rumors spread throughout Memphis that painted the family as performing violent, demonic rituals—a gross departure from the family’s Christian values. This myth has, of course, attracted an ongoing stream of thrill-seeking trespassers, ranging from curious teenagers to violent agitators, who have gone so far as to fire weapons into the property. Soon after the article was printed, Harris retreated into the confines of the Temple grounds, sharing his work only with church members and trusted clients. Though harassment resulted in the closure of the Temple to outsiders, it remained a site of creativity and refuge for the Harris family and the spiritual home of the congregation and Doc’s clientele until his passing in 1995. His grandson Washington James “Mook” Harris, the current leader of the Temple, says people continue to come to the Temple to seek counsel; however, no other members of the Harris family have the gift of healing.17

There are many more artist-created places that could be seen as manifestations of sacred space—Joe Minter’s African Village in America (Birmingham, Alabama) and Dr. Charles Smith’s African American Heritage Museum and Black Veterans Archive (Hammond, Louisiana), both sites of collective memory and active protest; Margaret and Reverend Herman Dennis’s Margaret’s Grocery (Vicksburg, Mississippi), a tribute to romantic love and platform for religious faith; and Mary Proctor’s Art Yard (Tallahassee, Florida), a dense installation of healing artwork that erupted from personal tragedy. These artists harnessed their creative power to express joy and confront grief, to secure a safe place for themselves and their families, and to protect and promote the culture of their communities.

Many of these sites were created with the generous intention to be shared with the public. Though originally open only to select audiences, Pasaquan was restored several years ago by the Kohler Foundation and is now fully accessible to the public through the stewardship of Columbus State University. Pearl Fryar has been unable to tend to his topiary garden for several years, but it is being restored through a partnership with a consortium of organizations initiated by Jane Przbybsz, director of the McKissick Museum at the University of South Carolina.18 Visitors are welcome to stop by to see the conservation process led by the current artist-in-residence Mike Gibson, Fryar’s friend and fellow topiary artist. And while The Saint Paul Spiritual Holy Temple is still strictly private, the Harris family is currently considering the future of the site and the possibility of public access. The preservation of each of these sites has and will require continued investment from a substantial network, and they will only remain in situ through collective action involving the artists and/or their families and dedicated individuals and institutions. Born from a complex tangle of personal and public histories, material cultures, and the storied terroir of the American South, these artist-constructed sites are not just glimpses into the lives of creative individuals but passageways to radical ways of being in the world for ourselves and our communities.

Annalise Flynn is an independent art historian and curator based in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. She manages SPACES–Saving and Preserving Arts and Cultural Environments, the world’s largest repository of archival documentation related to artist-built environments, on behalf of the Kohler Foundation.NOTES

1. Tom Patterson, St. EOM in the Land of Pasaquan: The Life and Times and Art of Eddie Owens Martin (The Jargon Society, 1987), 100. Several people who knew Martin personally have noted that his recollections were not always consistent. Regardless, this essay leans heavily on Patterson’s book as it presents Martin’s stories in his own words.

2. Ibid., 113.

3. Leslie Umberger, Sublime Spaces & Visionary Worlds: Built Environments of Vernacular Artists (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2007), 50.

4. Ibid., 126.

5. Ibid., 169.

6. Ibid., 169.

7. Ibid., 171.

8. Artist, curator, folklorist, and friend of St. EOM Fred Fussell told me in an interview on February 21, 2022, that St. EOM’s primary influence was James Churchward’s series of books about the “lost continent of Mu,” a mythical continent in the Pacific Ocean that was the birthplace of humankind. The books include illustrations of patterns, symbols, and language present in Peruvian, Native American, Egyptian, and Mayan cultures—and many more. After St. EOM’s death in 1986, Fussell was one of the primary advocates for Pasaquan and was integral in the preservation of the site (along with the Pasaquan Preservation Society) until he was able to enlist the assistance of the Kohler Foundation in 2014.

9. It’s important to note that St. EOM was not isolated from Buena Vista, and was, in fact, an active participant in town meetings and events. Many artists who create environments have been mischaracterized as reclusive; however, these makers often created their environments specifically as sites of gathering, a place where the community could come to them.

10. Scott Galloway and Brent Pierson, directors. A Man Named Pearl. Tentmakers Entertainment, 2006. 1 hr., 18 min.

11. “Pearl Fryar Topiary Garden,” The Garden Conservancy, https://www.gardenconservancy.org/preservation/pearl-fryar.

12. Galloway and Pierson, A Man Named Pearl.

13. William Arnett, “Pearl Fryar: Sculpture Gardener,” Souls Grown Deep, https://www.soulsgrowndeep.org/artist/pearl-fryar.

14. Ibid.

15. Galloway and Pierson, A Man Named Pearl.

16. The Harris family is of African and Indigenous ancestry, and they identify as Black Indians.

17. The information presented here about The Saint Paul Spiritual Holy Temple was collected through several interviews by the author with Mook Harris, who continues to live at the Temple with his wife, and Judith McWillie, a longtime friend of the Harris family. McWillie is an artist and professor emerita of drawing and painting at the University of Georgia, and she is currently editing a book about the Temple.

18. The partnership to preserve Pearl Fryar’s Topiary Garden also includes the Atlanta Botanical Garden, the WeGOJA Foundation (formerly the South Carolina African American Heritage Commission), and the Garden Conservancy. Though the long-term future of the Garden is uncertain, the consortium is currently working to create a plan to secure the site in perpetuity. Update: Pearl Fryar’s Topiary Garden is now managed with the support of a new board of directors: Pearl Fryar Topiary Garden, Inc. The board has hired an expert topiary trimmer who works under Mr. Fryar’s direction. For more information, visit www.pearlfryargarden.org