Amelia Alvarez was born in Cuba when the island was a Spanish colony. Yet by Amelia’s ninth birthday, her home as she knew it no longer existed. The Cuban War for Independence, which U.S. imperial ambitions turned into the Cuban– Spanish–Puerto Rican–Filipino–American War, brought an end to Cuba’s colonial status as well as Cubans’ hopes for a truly independent island. When Amelia turned sixteen, U.S. troops occupied Cuba for the second time in her life. That year, 1906, she boarded the steamship Olivette and sailed 110 miles from the Port of Havana to Key West. Soft winds from the Florida Straits wrapped around Amelia as she passed through immigration and rested for a night. The next morning, she climbed aboard the same boat and journeyed another 250 miles northward through the warm waves of the Gulf of Mexico. Once the ship docked, Amelia descended the gangway and walked into Tampa, Florida.1

At the turn of the twentieth century, Tampa brimmed with chaotic possibility.

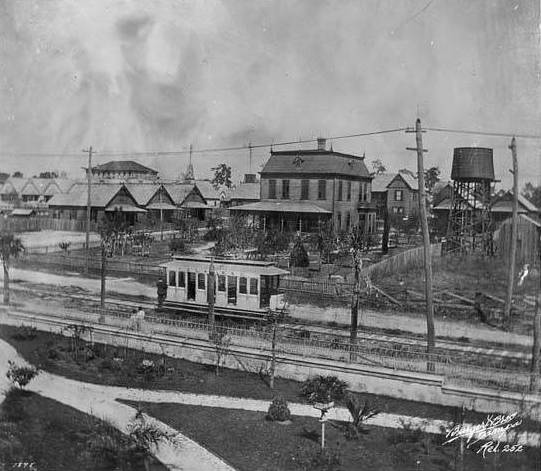

At the turn of the twentieth century, Tampa brimmed with chaotic possibility. Sounds of Spanish and English hovered in the heavy, humid air as Amelia navigated the throngs of people who crowded the port. More than one hundred passengers charged forward with their luggage in hand, while stevedores unloaded bales of Cuban tobacco leaves from the ship’s hold. Thirty years earlier, this swampy town featured little more than an obscure military outpost and a settlement of sweaty Confederates. But by the time of Amelia’s arrival, the Cuban cigar industry had changed nearly everything. Black and white immigrants, primarily from Cuba, along with others from Spain, Italy, and Puerto Rico, collided in Tampa as they searched for work in the city’s new cigar factories. Once hired, cigar workers “stripped, sorted, and bunched [tobacco] leaves,” then “rolled, banded, and boxed cigars.” The labor of these women and men transformed Tampa into the leading industrial center of the state, while their bodies, cultures, and politics created an international borderland in Jim Crow Florida. On the dock, Amelia stayed near her family, for she had not come alone. Her sister and brother-in-law, their two children, and three aunts arrived together with fifty-six dollars between them. As the family of eight emerged from the bustling masses, they likely boarded a streetcar to carry them six miles down the road to their new home in a neighborhood called Ybor City.2

To Amelia, Ybor must have felt familiar and foreign at the same time. Red-brick buildings with Moorish arches lined the streets, while ornate wrought iron twisted across glass windows and framed outdoor patios. Architectural remnants of colonial Spain seemed to echo through the streets, but it was the politics of Cuban independence that lived in people’s homes. Some of Amelia’s neighbors told tales of when José Martí, the famed Cuban poet and revolutionary, organized and collaborated with cigar workers to bring an end to Spanish rule in Cuba. Although this fight ended in 1898, when Amelia was nine years old, the community she joined in Ybor remained unapologetically anticolonial, pro-labor, and radically leftist in their self-proclaimed exile. From the perspective of Amelia’s neighbors, Ybor City served as their sanctuary from the restrictive imperialist agendas and the oppressive, anti-labor, antidemocratic conservative forces that lingered in their homeland even after the Spanish relinquished claim over the island. The two-story Centro Obrero (Labor Temple) stood at the helm of this neighborhood and operated as the space where women and men organized unions, planned strike actions, and created a culture of labor on their own terms. Cigar factories defined the city landscape and separated Ybor’s immigrants from Tampa’s Anglo residents—a racialized border that likely seemed uniquely American. De jure segregation generally did not exist in Cuba during Amelia’s lifetime, but de facto segregation did and Amelia likely recognized the practice. As a Cuban woman with white skin, however, being the subject of segregation would have been a new experience that made her acutely aware of her place within the South’s racial hierarchy.3

Inside Ybor City, Amelia found acceptance. The things that Anglos believed made her seem different—her appearance, her labor, her politics, her traditions, and her language—were foundational elements that bonded this immigrant community. Despite living in a new country, Amelia never had a problem with communication because nearly everyone in Ybor spoke Spanish, and those who did not learned upon arrival. Sicilian grocers transformed their markets into hybrid bodegas as they sold Spanish chorizo alongside Italian pickled vegetables and elevated what is now known as the Cuban sandwich. The local version of this delicacy stacked layers of mojo-marinated roasted pork, boiled ham, and hard salami on slices of Cuban bread dressed with a swipe of yellow mustard, a piece of Swiss cheese, and a sliver of crisp dill pickle. According to community lore, the last three ingredients reflected the food traditions of Jewish merchants who came to Tampa in search of refuge from the escalation of anti-Semitism in Romania and Germany. Many of these families sold fabrics, clothing, shoes, and auto parts in dry goods stores, while others used their profits to purchase cigar factories of their own.4

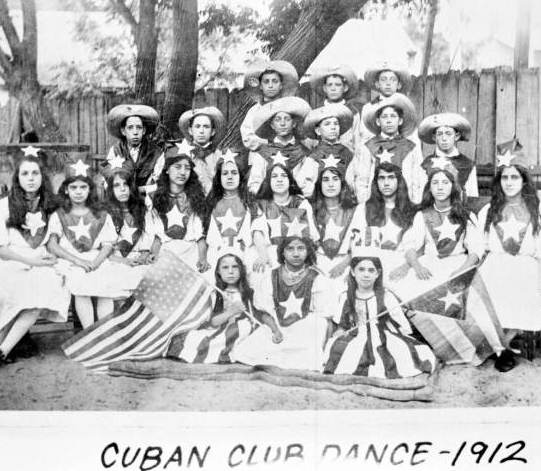

Spanish-language newspapers thrived in Ybor and reported daily news from Havana, Madrid, Key West, and Tampa. This vibrant print culture not only kept Amelia and her neighbors informed of global affairs and local events but made Ybor City an integral hub within a cross-national network of leftist activism and intellectualism that reached from the Caribbean to the Americas and across the Atlantic Ocean. As Amelia walked through the streets of Ybor City, she may have brushed shoulders with women such as Luisa Capetillo and Luisa Moreno—Latina feminist labor organizers and leftist thinkers—as well as Eugene V. Debs and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn—leaders of the socialist and communist movements—all of whom visited, organized, or sought refuge from political persecution in Ybor City. Each Saturday, the Afro-Cuban rhythms of rumba and the melodies of danzón, once outlawed in Spanish-controlled Cuba, spilled out from the ballrooms of the centros (mutual aid societies) and filled the streets. Yet as Amelia twirled across the dance floor of the Círculo Cubano (Cuban Club), she would have noticed that the Black Cuban women and men who worked beside her in the cigar factory were absent from this space. According to her neighbors, when the city of Tampa annexed Ybor City and made it part of Hillsborough County in 1887, Anglo political powerholders mandated that the centros segregate their membership and create a separate club for Afro-Cubans. La Sociedad de la Unión Martí-Maceo, the mutual aid society built by and for Black Cubans, emerged as a result of this moment. The Ybor City of Amelia’s youth was a place where multiracial, multiethnic Latina/o self-determination endured under the watchful eye of a reconstructed southern order.5

After nearly two years of living and working in Ybor, and shortly after celebrating her seventeenth birthday, Amelia met and married a Spanish immigrant named Pedro Blanco. The young couple moved down the street and rented a house near their families. When Amelia looked out her front door she would have seen rows of identical, whitewashed, shotgun houses that sat on narrow lots and flanked Ybor City’s wide dirt roads. In many ways, Amelia’s neighborhood was the turn-of-the-century version of a cheap housing development—a company town built for profit, not for comfort. In wintertime, families pasted old newspapers to the walls in hope of stopping cold air from seeping into the house. During summertime, the wooden planks expanded and softened from the inescapable humidity that penetrated the wood. Although the casitas were imperfect, people made do. These homes, flaws and all, were better than the lodgings most cigar workers could access in Cuba or in smaller cigar-working towns such as Key West. Amelia spent her days in the cigar factory and her nights gossiping on her front porch or gambling with other women in secret. Each night after dinner, her husband joined the men of Ybor at one of the local cantinas, where the sounds of clinking dominoes cut through the smoke-filled room and the scent of whiskey clashed with the smell of sweet tobacco and the bellows of masculine laughter. I imagine that, in the absence of men, Amelia and her friends talked about everything from politics and children to money and memories of Cuba, Spain, and Italy.6

Amelia created a life in Ybor City, but she never fully let go of the island. She and Pedro had four children—Delia, Pedro, Margot, and Dalia—yet only the last three survived infancy. Her sister, Concepcíon Camero, rented the house next door, until she and her three sons moved to Puerto Rico, where they stayed. Amelia visited her parents and siblings in Cuba roughly once a decade and always in July. At first, she traveled by water, retracing her original path to Tampa. By the 1940s, however, the steamships stopped sailing and Amelia flew Pan American Airways. Every time Amelia left Florida she used her Cuban passport because she never applied for U.S. citizenship. Perhaps U.S. citizenship seemed unnecessary, perhaps it seemed impossible to obtain, or perhaps Cuban citizenship was a part of herself she never wished to surrender. In 1952, at the age of sixty-three, Amelia passed away and was buried in Ybor City, Florida.7

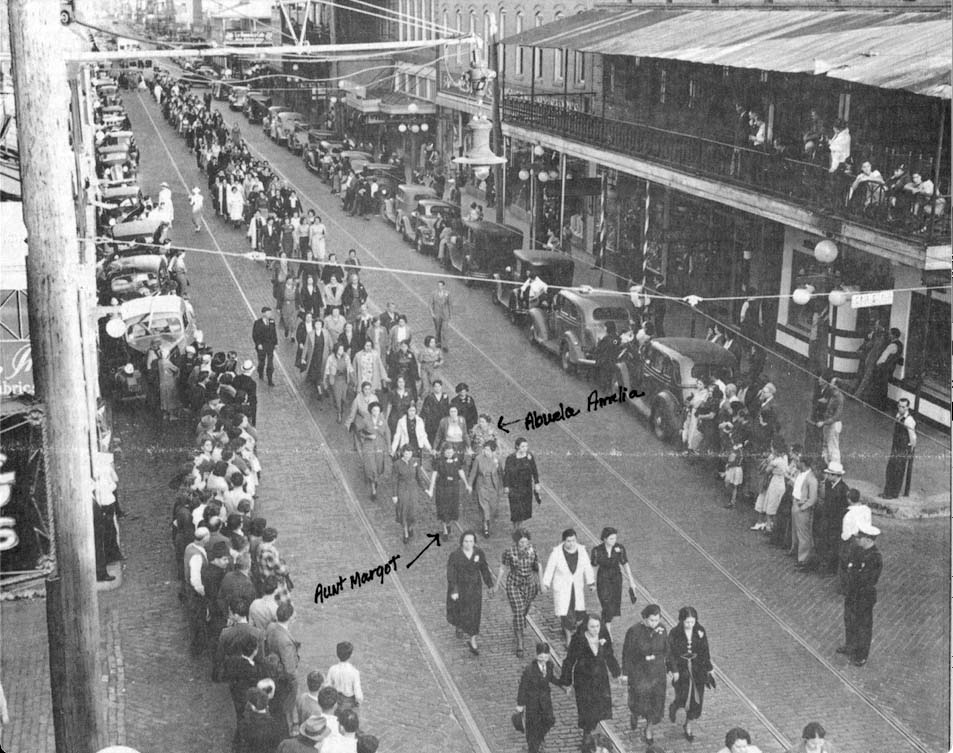

I learned about Amelia when I was a teenager. My grandmother, Norma Alfonso, showed me an article she clipped from the Tampa Tribune in 1990, roughly twelve years earlier. “Sarah, come look at this,” she yelled, calling me over to her rose-colored kitchen island. On the counter my grandma placed a white, two-inch, three-ringed binder I had seen many times before. Norma, who was born in Ybor City in 1931, saved anything and everything she found about the old neighborhood. Placemats from lunch counters, pamphlets from museums, excerpts from books, and articles from newspapers all found their way into her portable archive. As I took a seat in the kitchen, my grandmother slipped the pristine clipping from its acetate sleeve, extended her finger, and pointed at two women in a reprinted photograph. “This is Abuela Amelia,” she said, “and here’s her daughter, your Aunt Margot.” The black-and-white image captured a sea of women linked arm in arm marching through what I recognized as La Avenida Séptima (Seventh Avenue), the main thoroughfare of Ybor City. As I sat there gazing at the picture, Norma drew two arrows on the clipping and labeled the women in our family.

For as long as I can remember, my grandmother was on a one-woman mission to be sure my sister and I never forgot Ybor City. She drove us through the neighborhood, told us stories of our families, and kept traditions alive. Even before I saw the clipping, I knew Amelia was my grandmother’s favorite grandparent. Like Norma, she hated the beach but loved to read. Amelia had a talent for cigar making, a passion for bingo playing, and infectious joie de vivre. Those who knew her say she was loud and outspoken, a family trait that has survived generations. According to my grandfather, Gus Alfonso, Norma’s husband, “Amelia was an activist who was always up to something” and the foil to his self-proclaimed respectable, rule-abiding family. In reality, his father was a member and organizer of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA)—a truth he once revealed with a whisper and a look that made clear we would never revisit the subject. Despite the many stories Norma shared, she never told me the context of the image. Instead, I had to search for this answer on my own. In the process, I found that there was much more to Ybor City and the women in my family than my grandma was willing to explain. After all, sometimes it is the stories we hold back, rather than the ones we share, that reveal the essence of who we are.8

Excerpt from Ybor City: Crucible of the Latina South (UNC Press, 2023). Reprinted with permission.Sarah McNamara is Assistant Professor of History and core faculty in the Latina/o/x & Mexican American Studies Program at Texas A&M University. McNamara’s research centers on Latinx life, women and gender, immigration, and labor histories in Florida, the US South, and the modern United States. Her first book, Ybor City: Crucible of the Latina South (2023), is the history of three generations of migrant, immigrant, and US-born Latinas and Latinos— predominantly from Cuba, the Caribbean, and the Americas—who collided in Tampa, Florida, between the late nineteenth and the mid-twentieth centuries.NOTES

- Amelia was born in San Antonio de los Baños, Cuba, a rural town roughly fifteen miles from Havana. Louis A. Pérez Jr., Cuba and the United States: Ties of Singular Intimacy, 3rd ed. (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2003); Louis A. Pérez Jr., “Incurring a Debt of Gratitude: 1898 and the Moral Sources of United States Hegemony in Cuba,” American Historical Review 104, no. 2 (April 1999): 356–98. Note to readers: I use Spanish-language sources throughout this monograph. All translations, unless otherwise noted, are mine; Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at Key West, Florida, 1898–1945, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787–2004, Record Group 85, NARA, accessed via Ancestry.com, Florida, Passenger Lists, 1898–1963. The SS Olivette was part of the Plant System of steamships and railroads; see “Map of the Plant System of Railway, Steamer and Steamship Lines and Connections,” 1899, Touchton Map Library Digital Archive, TBHC, Accession Number L2009.093.021, M Number M1529, accessed November 2020, http://luna.tampabayhistorycenter.org/luna/servlet/detail /TBHC~3~3~4606~4823: Map-of-the-Plant-System-of-Railway,?qvq=q:Plant;lc:TBH C~3~3&mi=30&trs=52.

- For detailed information on the construction of the SS Olivette and information on cargo hold and capacity, see Irwin Schuster, “SS Mascotte of the Plant Line 1885–1931,” Nautical Research Journal 61, no. 4 (December 2016): 246–48; Arsenio M. Sanchez, “The Olivette and Mascotte of the Plant Steamship Line,” Sunland Tribune 20 (1994): 49–50; Nancy A. Hewitt, Southern Discomfort: Women’s Activism in Tampa, Florida, 1880s–1920s (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001), 1. The term cigar worker refers to anyone who worked within the Cuban cigar industry, whereas cigar maker refers to someone who was a skilled cigar roller. The term in Spanish for cigar maker is torcedor but in Ybor City the most common colloquial term was, and is, tabaquera/o. In this book, I use tabaquera/o most frequently but torcedor is most precise. See Nicho- las Foulkes, Cigars: A Guide (London: Penguin Random House, 2017), 146; Robert P. Ingalls and Louis A. Pérez Jr., Tampa Cigar Workers: A Pictorial History (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003), 67; Gary R. Mormino and George E. Pozzetta, The Immigrant World of Ybor City: Italians and Their Latin Neighbors in Tampa, 1885–1985, 2nd ed. (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1998), 43; Between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the streetcar system was called the “street railway system,” as it ran not on electricity but on coal or steam and embedded railway tracks. In 1907, a more formal and citywide system of street-cars emerged. However, because the distance between the Port of Tampa and Ybor City is six miles, it is likely that the Alvarez family took the railway car to Ybor City. For more, see Meeghan Kane, “Tampa’s Trolleys: Innovation, Demise, and Rediscovery,” Sunland Tribune 30 (2005): 31–43; Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at Key West, Florida, 1898–1945.

- Louis A. Pérez Jr., “Cubans in Tampa: From Exiles to Immigrants, 1892–1901,” Florida Historical Quarterly 57, no. 2 (1978): 129–40. Note: Anglo is the term used by Latinos in Tampa to describe people who are non-Latino, non-Black, native-born, and white; While Cuba generally lacked legislation that codified the segregation of space based on race, outside of the slave codes, this does not mean that segregation on the basis of race was less real or that it did not take place. On how de facto practices of racial discrimination effectively and systematically segregated the urban landscape, see Bonnie A. Lucero, A Cuban City, Segregated: Race and Urbanization in the Nineteenth Century (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2019), especially 5–6; Perla M. Guerrero, Nuevo South: Latinas/os, Asians, and the Remaking of Place (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017).

- Braulio Alonso Jr., La Gaceta, June 27, 1997; Federal Writers’ Project, “Dominica Guinta, Interview” (unpublished manuscript, 1941), SCUSF; Sammy Argintar, interview with Yael V. Greenberg-Pritzker, March 29, 2000, quoted in Ingalls and Pérez, Tampa Cigar Workers, 152; see also Mormino and Pozzetta, Immigrant World; Hewitt, Southern Discomfort; Susan D. Greenbaum, More than Black: Afro-Cubans in Tampa (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002); The history of the Cuban sandwich is hotly contested and debated. Cubans from Miami have a version of the sandwich (no salami), which some claim to be the original. Meanwhile Latinas/os from Ybor claim that the sandwich originated in Ybor City (with salami). New research from Andrew T. Huse, Bárbara C. Cruz, and Jef Houck has documented the history of this sandwich and suggests that there was no singular or typified “Cuban sandwich” on the island, but instead there were many versions. However, the version of the sandwich I described in the text is what is recognized today as the Cuban sandwich in Ybor. For more, see Andrew T. Huse, Bárbara C. Cruz, and Jeff Houck, The Cuban Sandwich: A History in Layers (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2022). For a local perspective of this origin story, see “Our Family and Your Family: Where It All Begins,” Restaurant Brochure, La Segunda Central Bakery, Ybor City, Florida, n.d.; “The Mayor’s Hour—Tampa Traditions, La Segunda Bakery,” May 4, 2017, City of Tampa, accessed September 2022, https://www .youtube.com/watch?v=M9_B9yWsR9c; Andrew T. Huse, “Welcome to Cuban Sandwich City,” Cigar City Magazine, January–February 2006, https://issuu.com/cigarcity magazine/docs/jan_feb_2006/16. For assorted stories of Tampa food culture, see Andrew T. Huse, From Saloons to Steak Houses: A History of Tampa (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2020). Mojo is a marinade often used in Cuban cooking. In Tampa, it is made of sour orange juice, olive oil, garlic, salt, pepper, and oregano. This marinade breaks down meat and penetrates it with bright flavors; Yael V. Greenberg-Pritzker, “The Princes of Seventh Avenue: Ybor City’s Jewish Merchants,” Sunland Tribune 28 (2002): 55–68; Huse, From Saloons to Steak Houses; Mormino and Pozzetta, Immigrant World. Note that over time Jewish and German immigrants were most likely to purchase cigar factories and move out of Ybor City as part of the merchant class and the middle class.

- On Cuban dance and music traditions, see Ned Sublette, Cuba and Its Music: From the First Drums to the Mambo (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2004); Christina D. Abreu, Rhythms of Race: Cuban Musicians and the Making of Latino New York City and Miami, 1940–1960 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015); see also Mormino and Pozzetta, Immigrant World; Hewitt, Southern Discomfort; Greenbaum, More than Black; Nancy Raquel Mirabal, “De Aquí, de Allá: Race, Empire, and Nation in the Making of Cuban Migrant Communities in New York and Tampa, 1823–1924” (Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan, 2001); Frank Andre Guridy, Forging Diaspora: Afro-Cubans and African Americans in a World of Empire and Jim Crow (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010). See also chapter 3, “Surviving,” in this book.

- Pedro Blanco and Amelia Alvarez, marriage license, Hillsborough County, Fla., 1907, Hillsborough County Marriage Records, Digital Collections, SCUSF, accessed June 2020, https://digital.lib.usf.edu/SFS0044124/00001?search=Blanco; For a description of the neighborhood and the creation of women’s communities, see Jose Yglesias, The Truth about Them (1971; repr., Houston, Tex.: Arte Público Press, 1999). Other testimonios by Yglesias that chronicle the neighborhood and provide historic texture of the community include Jose Yglesias, A Wake in Ybor City (1963; repr., Houston, Tex.: Arte Público Press, 1998); Jose Yglesias, Home Again (1987; repr., Houston, Tex.: Arte Público Press, 2002). A testimonio is a first-person narrative that examines experiences of social and political inequality. At times, the author changes the names of main characters and fictionalizes certain aspects of personal experience to represent those of a broader community. This form of memory work is common in Latina/o and Latin American writing. Note: Jose Yglesias did not use accent marks in his name—the exclusion is intentional; For more on the tradition of women and front porch discussions, see Yglesias, The Truth about Them; see also chapter 2, “Resisting,” in this book. During the first ten years of Amelia’s life in Ybor City, her neighbors were all Cuban women. See United States Census Office, Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910.

- Delia Blanco, Amelia’s first daughter, did not survive. In the 1910 federal census, Amelia Alvarez noted that she had one child and zero living. Immigration documents reveal that she took Delia to Cuba when she was nine months old. See Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910; Delia Blanco, February 7, 1910, Woodlawn Cemetery, Tampa, Fla., Ancestry.com, U.S., Find A Grave Index, 1600s–Current, accessed November 2020, www.findagrave.com/memorial/35241301/delia-blanco; Amelia Blanco, December 17, 1952, Centro Español Memorial Cemetery, Tampa, Fla., Ancestry.com, U.S., Find A Grave Index, 1600s–Current, accessed November 2020, www.findagrave.com/memorial/57783120/amelia-blanco.

- Amelia’s grandson, Nelson Pino, remembers that when she passed away they found little bags of coins hidden throughout the house. These were pouches of her gambling money. Nelson Pino, discussion with the author, June 2020, field notes in the author’s possession; Gustavo Jesus (Gus) Alfonso, discussion with the author, June 20, 2020, field notes in the author’s possession.