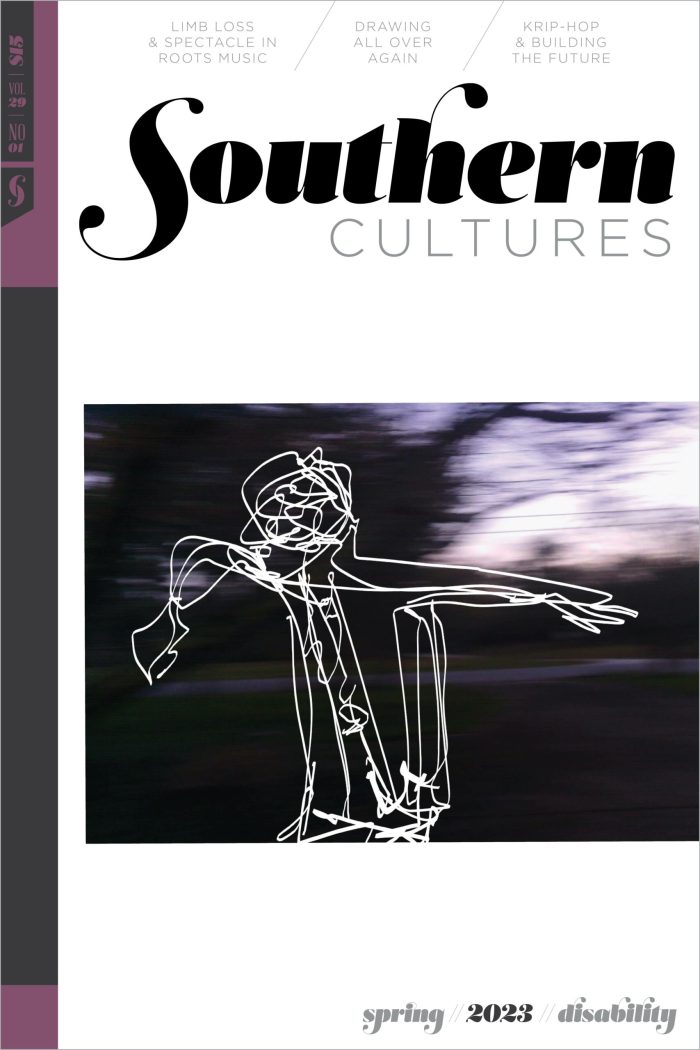

A middle-aged white man in three-quarter-length view proudly fills the frame of the black-and-white photograph (fig. 1). He stands on a cracked cement landing beneath a leafless oak tree. Behind him, peeling plaster reveals a crumbling, low-slung brick wall, over which a tangle of brambles gives way to a field bounded on the left by an old rail fence and on the right by dense woods. The man appears as worn as the landscape he inhabits: his hair is disheveled, his chin shaded with stubble, and he leans ever so slightly on a walking stick. His dark wrinkled work shirt is open at the collar, revealing a worn undershirt, and the uppermost buttons of his light-colored trousers, which are held up by suspenders, are missing. His paunchy stomach causes the waistband of his pants to fold over, its shadow echoing the deep contours of his downturned mouth, fleshy jowls, and furrowed brow. But he stands tall, filling the foreground as he squints and looks down over the right shoulder of an imagined viewer.

Who is this man? Why has he taken a break from his daily routine to pose for Eudora Welty (1909–2001), the young woman who visited Rodney, Mississippi, in the late 1930s and early 1940s, snapping pictures and jotting notes that would inspire a novella, short story, and essay? We may never fully know his story, but, inspired by the work of Saidiya Hartman, Stephen Best, and others who ask us to account for the absences in the archive, this essay searches Welty’s photograph for clues to animate his life and the lives of others like him who lived in Mississippi during the Great Depression.1

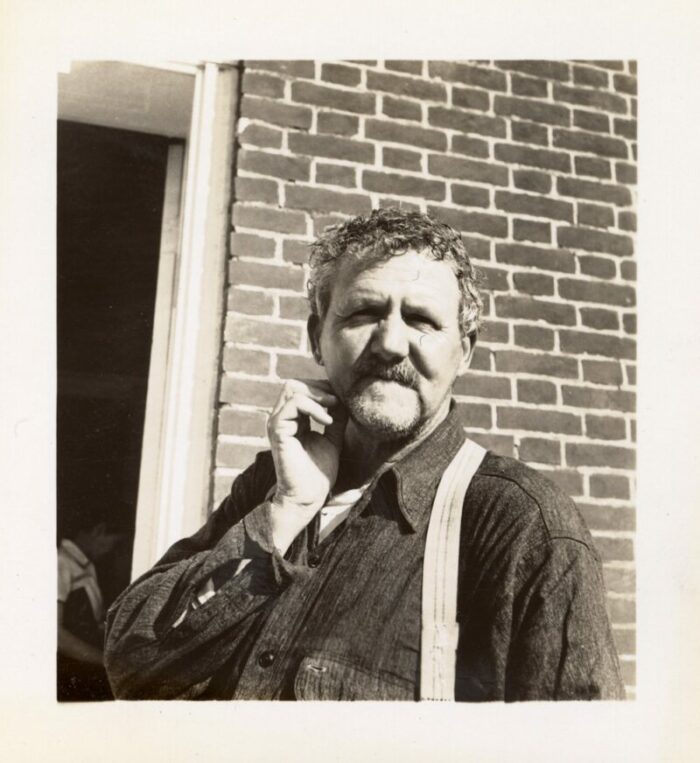

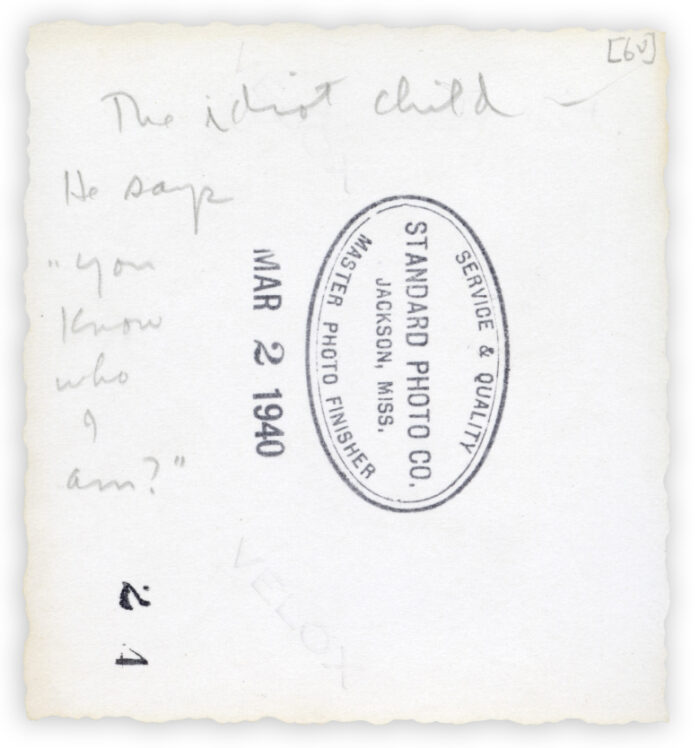

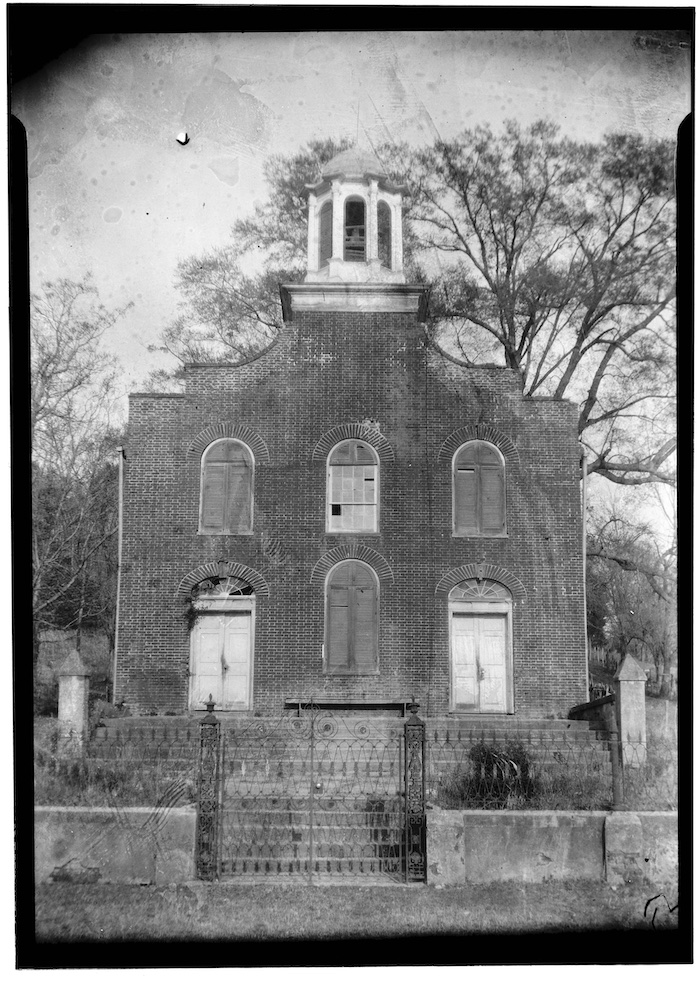

The subject’s identity is revealed in a note Welty scribbled on two photos she sent her close friend John Robinson in March 1940 (fig. 2). On the reverse of one, she wrote, “The idiot child—He says ‘you know who I am?’,” while on the other she inscribed his answer, “I’m Mr. John Paul’s boy.” Welty subsequently published his portrait in One Time, One Place: Mississippi in the Depression, A Snapshot Album (1971 and 1996), under the title “A village pet”/Claiborne County. An enlarged cropped version of the same negative was included in Eudora Welty Photographs (1989 and 2019), but titled Village pet, “Mr. John Paul’s Boy”/Rodney/1930s. The variations in these printings, as well as the snapshots Welty sent Robinson, reveal the photograph’s setting as the steps of the Old Rodney Presbyterian Church. “Mr. John Paul’s Boy” stands facing south. Behind him, to the right, is Rodney Cemetery, to the left is Muddy Bayou Road, and visible, to his right, is a sliver of the church’s brick façade. Welty relayed to Robinson that the man offered to guide her through Rodney’s Cemetery, and she must have taken him up on the offer, because the Eudora Welty Collection at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History has three images of him in its files, one of which—negative 26—was taken in the cemetery. Welty took other photographs of Rodney, as well, such as Home, ghost-river town/Rodney/1930s and Lilies on graves/Rodney cemetery/1940s (fig. 3), both of which were published in Eudora Welty Photographs.2

Rodney is in southwestern Mississippi, about thirty miles northeast of Natchez on the northern edge of Jefferson County. Home to the Indigenous People of the Natchez Nation, the area was claimed in 1763 by the French, who called it Petit Gulf, and renamed Rodney in 1814 to honor Thomas Rodney, the Chief Justice of the Mississippi Territory. Located in one of the richest cotton-producing regions in the South, Rodney was home to Rush Natt, a planter, physician, enslaver, and scientist, who, in 1820, developed Gossypum barbadense, better known as “Petit Gulf” cotton, a strain engineered to grow tightly and slide easily through the gin. The success of “Petit Gulf” cotton, coupled with the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, encouraged a land rush, and Rodney became one of the busiest ports on the Mississippi River with enslaved laborers planting, harvesting, ginning, baling, and loading millions of pounds of cotton onto the steamboats that traveled downriver to New Orleans. Rodney boasted numerous grand plantation homes, including Nutt’s Laurel Hill and Zachary Taylor’s Buena Vista, as well as thirty-five stores, Mississippi’s first opera house, and nearly five thousand residents.3

“Mr. John Paul’s Boy” stands on the steps of the Old Rodney Presbyterian Church, whose cornerstone was laid in 1829 (fig. 4). The church withstood bombardment during the Civil War—a cannon ball is still lodged in its façade—but, today, the church and the town are all but abandoned. Ravaged by two yellow fever epidemics, the Civil War, floods, fires, and the loss of its port when a sandbar caused the Mississippi River to shift west in 1870, Rodney was unincorporated by Governor Theodore Bilbo in 1930. When Welty visited Rodney in the late 1930s, “The river had gone, three miles away, beyond sight and smell, beyond the dense trees. It came back only in flood.” So vivid are Welty’s descriptions of Rodney in “At the Landing” and The Robber Bridegroom that, one hot summer afternoon in 1983, Welty’s biographer Suzanne Marrs went in search of “the clamor, the danger, and the incipient prosperity depicted in The Robber Bridegroom,” but found only a “smattering of wooden houses, some obviously occupied and others boarded up and abandoned.” Other dutiful pilgrims have followed, drawn by ghost stories and antebellum ruins. Is the lure of Rodney present in Welty’s photograph of “Mr. John Paul’s Boy”? Traces of the town’s grandeur have faded, but the primary subject of the image conveys dignity and composure; he stands ready to assist the young Welty, to give her a tour of his hometown, and to answer any questions she may have about those buried in the cemetery just visible beyond his left shoulder.4

Welty described him as “the idiot child,” although it is doubtful his IQ was less than twenty-five, the standard by which that term would apply. (The 1930s terminology for a person with a mild intellectual disability was “moron,” whereas one with a moderate disability was labeled “imbecile,” and only a person with the most profound disability was labeled an “idiot.”) As historian Steven Noll notes, “researchers and professionals invoked a myriad of terms to identify people as intellectually below average,” and laypeople did not always follow scientific guidelines. Noll observes that even doctors used these labels with varying degrees of accuracy. Despite referring to him as the “idiot child” and “village pet,” terms that strike us today as callous but that were common for the era, Welty recalled him with affection, including his photograph in several of her books and mentioning him in interviews, saying, “He showed me the church, and where the post office was, and he told me he asked every day but he’d never got a letter in his life. So I used to send him cards sometimes. Never fear, the whole of Rodney looked after him.”5

Indeed, members of the Rodney History and Preservation Society still remember him fondly. They say his name was Charlie and that he was born in Rodney in 1888. Census records show that his father, John Ernest Paul, served as the Town Marshall and was born in 1852, and that his mother, Lottie Klare, was born in 1859. They were married on April 28, 1880, and had five other children: Nonie, Estella, John, Mary (called Mamie), and Corinne. Corinne married Walter Bemiss, the postmaster for Jefferson County, and Charlie (who was the middle child) and his mother were listed as living with Corinne and her family in both the 1930 and 1940 census.6

As was typical at the time in rural Mississippi, Charlie Paul appears to have lived in Rodney with family members until his death. Rodney is about one hundred fifty miles west of Ellisville, the location of the Mississippi School and Colony of the Feebleminded, which opened in 1921 when eight patients were transferred there from the Mississippi State Insane Hospital in Jackson. As sociologist N. B. Bond observed in 1925, “At Ellisville the state has founded the meager beginnings of an institution for the feebleminded which by crowding now cares for 100 boys.” In 1929, the name was changed to the Ellisville State School, which remained consistently understaffed and underfunded, with patients often released due to lack of funds. After losing an appropriation promised by the state in 1933, the Board of Trustees ordered the school to reduce the number of students immediately and many children were returned to their families. As the trustees reported, “Many of these [children] had no homes to which they could be returned, and the work of forcing them back into the communities became, to those of who were familiar with the facts, obviously a tragic refusal of the State to carry out its obligations to its helpless wards.” Perhaps, but for many, life in their hometown was preferable to institutionalization. Paul was thirty-three when the state school opened, and lucky that he was surrounded by a supportive family of some means and a community who considered him one of their own. His freedom and relative autonomy were in stark contrast to the inadequate care minors received in state-run facilities.7

Still, institutionalizing people with intellectual disabilities was common during the nineteenth and well into the twentieth century. The segregation of those with disabilities is tied to modernity and what Lennard J. Davis calls the “hegemony of normativity” and Robert McRuer terms “compulsory ablebodiedness.” In the preindustrial era, the family “bore primary responsibility for those who could not labor and thus care for themselves—whether due to youth, old age, or mental, cognitive, or physical disabilities,” but by the nineteenth century, as the nation began to industrialize, “asylums for the insane” and “colonies for the feeble-minded” were established. In 1818, “several idiotic children were received and given instruction at the American Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb at Hartford,” Connecticut, and in 1848 the country’s first school for people with intellectual disabilities, the Massachusetts School for Idiotic and Feeble-minded Youth, opened in South Boston. New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio quickly followed suit, as schools “designed for the education and management of all children who by reason of mental infirmity are not fit subjects for ordinary school instruction” opened across the industrialized North. Many of these institutions were consistently underfunded and overcrowded, and reports of improper care of residents, including neglect, abuse, and rape, were not uncommon. The South, however, which remained largely rural, was slow to create public institutions. Instead, the care and support of those displaying atypical neurologies or intellectual impairments fell to the family and extended community, with most small southern towns supporting a “village pet,” who was viewed with a mix of compassion and affectionate humor.8

Welty was fascinated by both rural life in small-town Mississippi and those who pushed the boundaries of normative society. As she said, “it was just an amazing world, with these strange figures roaming through the wilderness.” Literary scholars have noted that Welty’s stories include numerous “strange” characters, some of whom exhibit what may be described today as physical or mental impairments. Jenny Lockhart’s mother was “raving,” Billy Floyd was alternately described by the townspeople as a “wild man” (also a “Gipsy,” a “Natchez Indian,” and a “bastard”), Ruby Fisher was “slow all her life,” Albert and Ellie Morgan were deaf; Keela “has a clubfoot,” Stella Rondo, Uncle Rondo, Sister, Clytie, Henry, and Octavia all exhibit some degree of what may be described today as neural diversity; and Lily Daw was, if not intellectually disabled, at least considered so by “the ladies,” who threatened to send her to Ellisville if she didn’t marry a respectable man. These characters may seem larger than life, but, as Donna Tartt once remarked to Ann Patchett, “the reason it’s so impossible to write about Mississippi is that everyone thinks you’re exaggerating.” Welty’s stories are full of “exaggerated” characters with atypical bodies and minds who come from nonnormative families and behave in nonconforming ways, and even as responsibility for care was shifting from the family to the state and many eugenicists were arguing for sterilization and control of those deemed mentally or physically unfit, Welty continued to write characters who defied societal expectations. Or, as literary scholar Mitch Frye notes, “Welty sometimes sought to shock the sensibilities of her southern readers, to make them question the racist and sexist societal norms historically associated with the region.” Of course, she also “shook the sensibilities” of her northern readers, challenging their preconceived notions of life in the South. Welty’s characters are intersectional; regionalism, racism, sexism, agism, and ableism converge in her stories, which resist assumptions, confront stereotypes, and expose prejudices. Welty’s photography operates in a similar way, exhibiting what Tobin Siebers characterized as an “aesthetics of disability” that inscribes its subjects, many of whom were otherwise marginalized and minoritized, with agency.9

Charlie Paul stands tall on the steps of Rodney’s oldest church, posing for both the photographer and future viewers. Welty, using the professional-grade Rolleiflex camera she held at her waist, shoots up, aggrandizing her subject and inscribing his body onto the landscape. The oak’s limbs branch into intersecting capillaries that frame his head like a crown, and the late-afternoon light emphasizes every texture: the cracks in the pavement, the grooves in the bricks, the wrinkles in his clothes, and the lines on his weathered face. Welty framed Paul a bit off-kilter: the ground is slanted, his cane akimbo, the orthogonal lines formed by the tree line on the left and the road on the right converging somewhere behind him but giving the impression that the landscape is slipping away to the left, sliding slowly down the embankment. The cumulative effect of Welty’s aesthetic choices is a portrait that invites a second look, that gestures to a life well lived. Disability is often constructed as an “absent presence”—something that is both apparent and ignored—but Welty’s portrait of Charlie Paul, the “village pet,” draws attention to both her subject’s humanity and his intellectual disability. In this, her photographic practice stands in contrast to convention, as evidenced by the thousands of photographs of the rural impoverished taken during the 1930s by now-famous photographers, including Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange, who worked for the Historical Section of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) and favored abject rather than disabled subjects. As Ryan Lee Cartwright notes, “FSA photography emphasized the potential of poor white rural families to be rehabilitated, and in doing so, publicly minimized connections between poverty, disability, and nonnormative family structures (even as eugenics remained an ‘absent presence’ in FSA photography).” The social welfare programs of the Great Depression focused on helping those “able-bodied” Americans who were “certified by a local agency” as capable of labor. Thus, much of the FSA’s output pictured women and children or men of working age and celebrated the rural nuclear family to foster viewer sympathy and garner political support for the New Deal. As Cartwright elaborates, “successful rural rehabilitation required normative, abled families, thereby excluding those who were economically vulnerable—precisely because they could not rely on their physical abilities and the social safety net of a family through blood or marriage.” Charlie Paul exists outside these normative structures, as he was excluded from physical labor and marriage, and, in contrast to much of the FSA’s collection, he presents viewers with an alternative view of labor, political economy, and disability.10

Robert Bogdan argues that photographs of people with disabilities reveal more about the photographer’s point of view than about the real lived experiences of people with disabilities, and while this may be true, Welty demonstrates that it is possible to present nonnormative subjects with sensitivity. Her photographs of Charlie Paul disrupt expectations, “index alternative domestic and family arrangements,” gesture to interdependency as a viable social model of relationality, and “resist visual normalization.” Although social scientists may have considered the lack of state-funded care in Mississippi as evidence of the South’s tragic backwardness, in light of the disability rights and independence movements of the 1980s and 1990s, Paul’s freedom, autonomy, and mobility may be best viewed as progressive. Paul was not sent to Ellisville; instead, he lived in his hometown and offered a service to his community, leading tourists through its famous cemetery and showing them around its historic church. The life of Charlie Paul was “enriched, enabled, and made possible” by communities of care, and Welty alludes to this community in her photograph of him on the steps of the church overlooking the cemetery that he knew so well. Charlie Paul was not a tragic figure. He was a son, a brother, and an uncle, an expert on the town’s genealogy, a keeper of its cemetery, and a valued member of his community. For her part, Welty “captured the fleeting moment” and took pictures that offer important glimpses into Paul’s life and subjectivity. Welty, who consistently used her stories to challenge traditional politics, similarly employed photography to upend expectations of age, race, gender, and ability and provide insight into the “amazing worlds” of people with cognitive impairments.11

This essay was first published in the Disability issue (vol. 29, no. 1: Spring 2023).

Keri Watson is an associate professor of art history at the University of Central Florida and an executive editor of Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art. She recently coedited, with Timothy W. Hiles, the Routledge Companion to Art and Disability (2022).

NOTES

I’d like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to Mary Pallon, Patricia Piazza Murphy, and Liz Friar of the Rodney History and Preservation Society for sharing their knowledge and recollections; Forrest Galey of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History for her tireless assistance; Charles L. Hughes for guest editing this special issue; and the editors and anonymous readers at Southern Cultures for their helpful suggestions.

- Eudora Welty, The Robber Bridegroom (Garden City: Doubleday Doran, 1942); Welty, “At the Landing,” in The Collected Stories of Eudora Welty(New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980; first published in The Wide Net and Other Stories, 1943); and Welty, “Some Notes on River Country,” Harper’s Bazaar 78 (1944), 86–87 and 150–156; Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (New York: W. W. Norton, 2019); and Stephen Best, “Neither Lost nor Found: Slavery and the Visual Archive,” Representations 113, no. 1 (2011): 150–6.

- Series 29a, Box 135, Eudora Welty Collection, Mississippi Department of Archives and History; Annette Trefzer, Exposing Mississippi: Eudora Welty’s Photographic Reflections (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2021), 92; Eudora Welty, One Time, One Place: Mississippi in the Depression, A Snapshot Album (New York: Random House, 1971), 108; and Eudora Welty, Eudora Welty Photographs (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1989), picture #27; Suzanne Marrs, The Welty Collection: A Guide to the Eudora Welty Manuscripts and Documents at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1988), 118.

- Jefferson County is just south of Claiborne County. Welty misidentified the location of the photograph in One Time, One Place but corrected her error in Photographs; Mary Carol Miller, Lost Mansions of Mississippi (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1996), 30.

- Harriet Riley and Ashleigh Coleman, “Haunted by a Ghost Town: The Lure of Rodney, Mississippi,” Mississippi Folklife, August 11, 2019, http://www.mississippifolklife.org/articles/haunted-by-a-ghost-town-the-lure-of-rodney-mississippi, accessed March 24, 2022; Eudora Welty, “At the Landing,” in The Collected Stories of Eudora Welty (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980), 241; Mary Hughes Brookhart and Suzanne Marrs, “More Notes on River Country,” Mississippi Quarterly 39, no. 4 (1986): 507, 508.

- Steven Noll, Feeble-Minded in Our Midst: Institutions for the Mentally Retarded in the South, 1900–1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 1–3; Eudora Welty, Eudora Welty Photographs (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1989), xxvii.

- Kelly Gomez, “Ghosts of the Mississippi: The Forgotten Town of Rodney,” The Forgotten South, https://theforgottensouth.com/rodney-mississippi-ghost-town-history-tour/, accessed March 25, 2022; Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910 (NARA microfilm publication T624, 1,178 rolls); Mississippi, US, Compiled Marriage Index, 1776–1935; and 1900 US Census; Census Place: Beat 5, Jefferson, Mississippi; Roll: 812; Page: 1; Enumeration District: 0089; FHL microfilm: 1240812; “Jefferson County,” The MSGenWeb Project, https://www.msgw.org/jefferson/census/rodney1930.html, accessed March 25, 2022.

- The first institution in the South for people with cognitive disabilities did not open until 1914, nearly one hundred years after similar institutions in the North. Steven Noll, “The Public Face of Southern Institutions for the ‘Feeble-Minded,’” The Public Historian 27, no. 2 (2005): 29; N. B. Bond, “The Physician and Mental Ills in Mississippi,” Social Forces 4 (1925): 329; Whitney E. Barringer, “The Corruption of Promise: The Insane Asylum in Mississippi, 1848–1910,” (PhD diss., University of Mississippi, 2016), 205; Ellisville, Biennial Reports of Eleemosynary Institutions 1931–1933, 57–58.

- Lennard J. Davis, The Disability Studies Reader (New York: Routledge, 1997), 10; and Robert McRuer, Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability (New York University Press, 2006), 10; Kim E. Nielsen, A Disability History of the United States (Boston: Beacon Press, 2012), 21–22; Walter E. Fernald, History of the Treatment of the Feeble-Minded (Boston: Press of Geo. H. Ellis Co., 1912), 2–4; Albert Deutsch, The Shame of the States (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1948), 132–34, and James W. Trent Jr., Inventing the Feeble Mind: A History of Mental Retardation in the United States (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 258; Noll, “The Public Face,” 29.

- Elizabeth Mehren, “Eudora Welty: A Life of Stories: 78-Year-Old Novelist Finds Strength and Continuity in the Written Word,” Los Angeles Times, November 13, 1987, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-11-13-vw-14019-story.html, accessed March 26, 2022; Susan V. Donaldson, “Making a Spectacle: Welty, Faulkner, and Southern Gothic,” Mississippi Quarterly 50 (1997): 567–583; Carol Ann Johnston, Eudora Welty: A Study of the Short Fiction (New York: Twayne, 1997); Matthew R. Martin, “Vision and Revelation in Eudora Welty’s Early Fiction and Photography,” Southern Quarterly 38 (2000): 17–26; William Solomon, “The Rhetoric of the Freak Show in Welty’s A Curtain of Green,” Mississippi Quarterly 68 (2015): 167–187; Annette Trefzer, “Welty’s Place in the Undergraduate Theory Classroom,” in Teaching the Works of Eudora Welty: Twenty-first Century Approaches, ed. Julia Eichelberger and Mae Miller Claxtson (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2018), 122–131; and Keri Watson, “Picturing Difference and Disability in the Classroom,” in Teaching the Works of Eudora Welty: Twenty-first Century Approaches, ed. Julia Eichelberger and Mae Miller Claxtson (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2018), 101–108. Whereas Harper Lee’s Boo Radley, William Faulkner’s Benjy, and John Steinbeck’s Lennie reinforced stereotypes about the South and disability (including that they were backward, depraved, dependent, and incompetent), Welty offered a different view of life in the South; Eudora Welty, “Lily Daw and the Three Ladies,” in The Collected Stories of Eudora Welty (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980), 5; Ann Patchett, These Precious Days: Essays (New York: HarperCollins, 2021), 88; Edward J. Larson, Sex, Race, and Science: Eugenics in the Deep South (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 1; and Cartwright, Peculiar Places, 51; Mitch Frye, “Astonishing Stories: Eudora Welty and the Weird Tale,” Eudora Welty Review 5 (2013): 75; Tobin Siebers, Disability Aesthetics (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010).

- Thomas Fahy, “Worn, Damaged Bodies in Literature and Photography of the Great Depression,” Journal of American Culture 26, no. 1 (2003): 15; Ryan Lee Cartwright, Peculiar Places: A Queer Crip History of White Rural Nonconformity (University of Chicago Press, 2021), 59; Works Progress Administration, WPA Workers’ Handbook (1936), np; Cartwright, Peculiar Places, 65.

- Robert Bogdan, Picturing Disability: Beggar, Freak, Citizen and Other Photographic Rhetoric (Syracuse University Press, 2012); Cartwright, Peculiar Places, 51; Larson, Sex, Race, and Science, 120; Jina B. Kim, “Toward a Crip-of-Color Critique: Thinking with Minich’s ‘Enabling Whom?,’” Lateral 6, no. 1 (2017): np; Welty, Eudora Welty Photographs, xv.