On a spring night in 1960, Miami detectives visited a popular nightspot, the Clover Club, where they gaped at a provocative striptease performed by Zorita, who writhed onstage accompanied by a live boa constrictor. They charged Zorita, as well as the manager of the club, with indecency. A city court judge eventually dismissed the charge. The decision was reported on the front page of Section B of the Miami Herald ’s Saturday, April 2, 1960, edition. Zorita was no stranger to headlines in the city, or even national, newspapers. She had also grown accustomed to such criminal charges; she regularly found herself in trouble with the law.

The other headlines scattered around Zorita’s story offer a snapshot of Miami, Florida, in that moment in its history. A story of how “Illegal Repairs Save Doomed Negro Shacks” was printed inches away from a report that informed readers of how a “Cuban Bomb Plot Wasn’t Political.” The former discussed how two “shacks” in Miami’s Central Negro District had been hastily and illegally repaired by their owner, which sufficed to save the condemned and boarded structures from demolition. Jim Crow practices, including restrictive covenants, had long kept Black Miamians confined to this area of the city. The repair of the shacks had “saved” them from the bulldozer so that white landowners could continue to exploit the Black tenants who lived there. The latter story concerned a man who had recently moved to Miami by way of Cuba, fleeing the 1959 Revolution. He confessed to hurling two homemade firebombs several weeks apart at the home of a well-known, high-ranking former Cuban politician named Anselmo Alliegro y Milá. The firebombing was part of a much larger wave of attacks and anticommunist anxieties in the city linked to Cuban refugees and the political crisis in Cuba. Much like the report of Zorita’s trouble with the law, these stories signaled a rapidly changing Miami, an often-overlooked city of the New South, located at the intersection of the Americas.2

Indeed, Zorita’s own story cannot be separated from events happening in Miami at that time—the city’s changing demographics, urban politics, and its distinct ethnoracial constructions of gender and sexuality. As the 1960 headlines suggest, Zorita’s story crisscrossed with conflicting visions of how the city would respond to calls to modernize and diversify its tourist-driven economy, define the city’s race relations and “color line,” accommodate new immigrants from the Caribbean and Latin America, and navigate boundaries of gender and sexual norms.

Zorita became a household name by engaging, and often challenging, the very social, political, cultural, and economic forces that pulsed through the headlines splashed across the city newspaper. Although she came to know Miami law enforcement and courts quite well over the years, Zorita—a white, non-Hispanic woman—sustained a long and successful career in burlesque and entertainment. And although her audiences consisted primarily of men, Zorita preferred the company and intimacy of women in her personal life, and today she would likely identify as a lesbian or queer woman.

Zorita’s life and career provide an important snapshot of Miami as it radically transformed from a sleepy city of the New South into a dynamic global city. Zorita was a pathbreaker who created spaces and platforms for other LGBTQ and marginalized people during a time when very few others were able or willing to do so. Though Zorita was not born or raised in the South, she spent most of her adult life living in Florida during a time of its radical transformation. The Miami that Zorita traversed during the peak of her career is a quintessential story of the New South and its evolving identity and character.

Becoming Zorita

Ada Brockette, the woman who became known as Zorita, was born on August 30, 1915, in Youngstown, Ohio. A strict Methodist couple adopted her as an infant. She and her family lived in Chicago for several years and, following some family troubles, Brockette dropped out of school at age fifteen, moved to California, and became a manicurist. She soon wedded a man studying to be a lawyer, ending the marriage just a few weeks later. Rebelling against the wishes of her conservative family, she began a career in burlesque while she was still a teenager. She took work as part of a traveling carnival and nudist colony that mostly performed in California. She was part of a troupe that featured several women frolicking mostly in the nude in a Garden of Eden–like setting. Customers paid to watch them in action.3

In these spaces, she learned how some entertainers used snakes as part of their carnival exhibitions, and she soon adopted them as part of her “exotic” burlesque acts. She confessed that snakes terrified her, but she knew that incorporating them into her routines would help set her apart. By the early 1930s, the carnival billed her as the highlight of its show: “Princess Zorida.” She took on the role of a high priestess with the ability to charm snakes. It featured nearly all the “exotic” tropes of the racialized Other, ones made more palatable to general audiences by way of her whiteness, femininity, and sexual prowess. Her character would be sold at auction in a slave market before being sacrificed to the Sun God.4

Zorita’s association with snakes gained her fame and notoriety. During a visit to Florida in February 1939, she made national headlines when police arrested her for walking down the streets of Miami with her six-foot-long “pet” snake, which she had on a leash. It was a clear publicity stunt to promote her appearances later that week at Minsky’s Burlesque in Miami Beach, which billed her as “Zorita and her snake . . . sensational!” Certainly, by then, her association with snakes had stuck, and there was no turning back.5

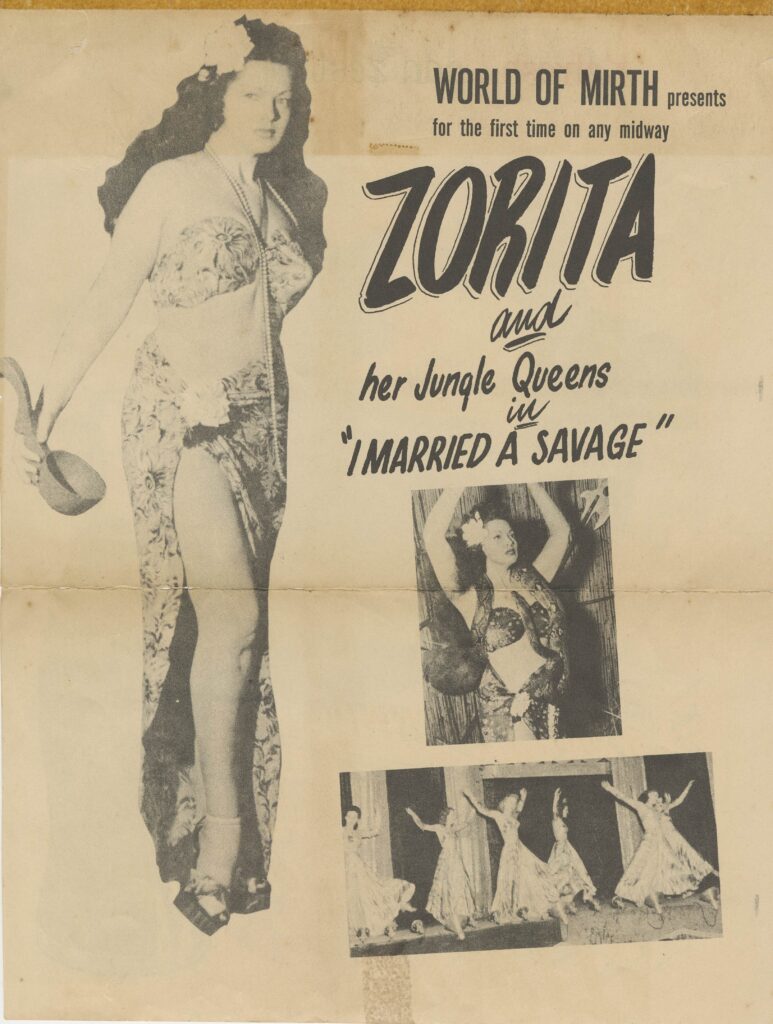

By the following decade, she was cast in her first starring cinematic role, a B-list film titled I Married a Savage. Released in 1949, the sexploitation film tells the story of a GI who washes ashore onto a Pacific island during World War II and meets an enchanting seductress, played by Zorita, with the ability to dance and snakecharm her way into a man’s heart. A dismal review of the film observed the racialized nature and exoticization of Zorita’s character in the film: “Who is the mistress of this jungle yurt? None other than Zorita, a white girl who has been brought up among the savages. . . . Isn’t this awful?”6

Zorita’s career catapulted in the 1940s and 1950s, an era that saw the gradual decline of burlesque as it gave way to more hardcore nudity and strip shows. Zorita combined those two worlds to great success and acclaim. During World War II, she was regularly featured as a pinup girl and sex symbol, reminding servicemen what they were fighting for. One magazine bluntly noted, “One look at her and we’re ready for the enemy, for Zorita is certainly worth defending.”7

Zorita was legally married three times; although all ended in divorce, her final marriage brought Zorita her only child. Zorita lived for several years in New York City, where a thriving nightlife helped her find steady work and stay in the headlines.

Miami: A Playground and Wide-Open City

But by the early 1950s, Zorita was among the thousands of people who moved to the growing city of Miami. The county that houses Miami nearly doubled in size from 1940 to 1950. Zorita “wanted to be a big fish in a smaller pond,” recalled her daughter, Tawny Petillo.8

Perhaps her move to Miami should come as no surprise; after all, since its founding in 1896, white urban boosters and developers had marketed Miami as a metaphorical playground for white pleasure-seekers. They capitalized on anti-Black violence and segregation, US empire building, and Indigenous removal and dislocation to bring new tourists and residents to the city.

Urban promoters touted Miami as a “fairyland” that centered white leisure, pleasure, entertainment, and opportunity, a culture that regularly also challenged gender and sexual norms. As early as the 1890s, urban designers and boosters sought to create an active artists’ colony to convert Miami’s frontier wilderness into a progressive and modern resort town for white leisure and consumption. They hoped to attract painters, sculptors, architects, photographers, writers, fashion designers, actors, performers, dancers, and singers. After all, as purveyors of creativity, individualism, and self-expression, artists often challenged the very idea of what could be socially acceptable in a given space. This included the transgression of gender and sexuality.9

By the 1930s, Miami housed a more visible and legible community of gender and sexually transgressive people, including some who lived openly as what we may think of as gay, lesbian, or bisexual today. Oftentimes, they were part of the city’s entertainment circuit and thus were central to fueling Miami’s tourist-driven economy. City powerbrokers often played a delicate balancing act over whether Miami would become a wide-open city that catered to the tastes and whims of tourists, or a model or moral city of the US South. These tensions, along with several others palpable in this city of the New South—including anti-Blackness, xenophobia, and class warfare—boiled over in November 1937 when nearly two hundred members of the Ku Klux Klan raided a gay bar called La Paloma in unincorporated Miami. Members of the KKK burned “a fiery cross” in front of the establishment, stormed inside, roughed up people and property, and “compelled patrons to leave,” threatening to burn the place down if they did not comply with their orders. La Paloma would later be raided by the police as well. As with many other places in the South and beyond, the evidence seems to suggest that some local law enforcement may have been among those who wore the hood the night of the Klan’s raid at La Paloma, or that they would have at least known the identities of some of those who did.10

While police raided gay bars in Miami—as well as participated in antivice campaigns that targeted nightspots where queer performers, gamblers, and strippers and other sex workers often converged—beginning in the late 1930s, area law enforcement seemed to have implemented a policy of permitting many queer establishments to operate during the winter season when tourists expected such offerings in the city. One newspaper referred to this unofficial policy as “Miami’s seasonal ‘face washing.’” From roughly late October to mid-March, the period then defined as peak tourist season, local law enforcement often permitted queer performances and nightspots to operate. But once paying tourists had largely evacuated the city, police would once again turn up the heat and sometimes even raid establishments that had not curbed their most risqué queer offerings. This became standard practice roughly until the mid- to late 1940s, when new social and political pressures led to campaigns against queer people and cultures.11

This catering to tourism that helped nudge Miami into being a more wide-open city also occurred, in no small part, to compete with the growing tourist markets in the nearby Caribbean—especially those in Havana, Cuba. The need to attract tourists and their dollars and pesos became more pressing for Miami’s promoters once commercial aviation made travel to cities like Havana more readily available in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Miami boosters pushed local politicians and law enforcement to embrace the idea of a wide-open city in their battle to compete with other accommodating “playgrounds” in the Caribbean. Miami promoters often touted their city as a “safer” and, at times, whiter, alternative to those Caribbean destinations, tapping into a deeply rooted anti-Black discourse in the process.12

It was the fact that tourist dollars and pesos reigned supreme in this fairyland, as well as Miami’s growing wide-open reputation, that would have especially appealed to a white woman like Zorita who made her living stripping and performing and who likely also knew that she could find spaces to express her same-sex desires. As a queer woman and burlesque dancer, Zorita would have also known that many of the strip joints in Miami often attracted queer workers and networks. La Paloma, for instance, hired gender-bending performers, often referred to as “pansies” during this era, alongside women wearing G-strings and brassieres who danced and stripped for their audience’s pleasure.13

How Cuba Shaped Miami

Cuba’s tourist industry of the 1940s and 1950s proved stiff competition for Miami, at least until the island’s communist revolution of 1959 shut down travel for US visitors. For years, Cuban guerilla revolutionaries fought to overthrow the corrupt administration of Cuban president Fulgencio Batista, who had long favored foreign investors, like those from the United States, and who permitted vice, graft, and sexual exploitation to run amok on the island. In fact, prior to the ousting of Batista and the victory of the Cuban Revolution of 1959, the US government launched an anticrime crusade in the early 1950s that pushed much of the illegal gambling and vice culture from South Florida to the Caribbean, especially Cuba.14

Miami had had deep connections to the Caribbean since its founding, and Zorita tapped into these racialized and neocolonial histories when she crafted her routines and performances in this New South city. For example, while Zorita had adopted her Spanish-sounding stage name early in her career, it took on new meaning once she arrived in Miami. It was certainly possible, if not likely, for her audiences to imagine her as white woman from the Caribbean. After all, the city not only had a long-established relationship with Cuba by this period, but also a growing Cuban population. By 1958, roughly ten thousand Cubans called Miami home, including many who had fled Batista and the political turmoil on the island. That number increased exponentially in the coming decades.15

In keeping with the racialized marketing strategy that took root by the 1930s and that sought to portray Miami as a safer and more accommodating playground than Havana, Zorita could provide her audiences a fantasy of a Caribbean “Other” made safe for their consumption through her whiteness. For example, Zorita had a residency at Miami’s Gaiety Club. A 1955 ad showcased her “Cuban Circus Revue” there, a few years before the communist takeover in Cuba. Her performance featured Zorita and her “famous snake dance” and mentioned the appearance of another woman billed as “Carmencita the Cuban Cuddlybear.” It also stressed, in Spanish (in an English-language newspaper), how “hay muchachas Latinas,” or the fact that the club featured Latinas. By the following decade, when thousands more Cubans called Miami home, Zorita was featured in another B-list film, originally titled “The Schooner Bay Caper” but released in 1969 under the name Judy’s Little No-No. Mirroring the anxieties of the era in cities like Miami, the film’s plot found a sexy female go-go dancer fleeing Cuban mafiosos and hitmen.16

Challenging Gender and Sexual Norms

Miami’s antigay political climate of the 1950s and 1960s also played out through a prism of Cold War gender and sexual anxieties, including a “lavender scare” that converged homophobia and transphobia with the era’s rampant anticommunism. And as gay and lesbian identities further crystallized in the 1950s, and gay communities became more visible in cities like Miami, so too did efforts to eradicate them. Miami law enforcement and politicians did away with the previous policy of relative tolerance and mutual benefit, and launched several aggressive antigay campaigns, which included purging gay teachers from schools and raiding gay hangouts, bars, and beaches. Local politicians also passed new laws to curb the visibility of gay communities and culture. Miami’s city council passed Ordinance 4586 in 1952, barring men from impersonating women. The following year, Miami Beach councilmen passed a similar law. Stripper and burlesque nightspots in Miami were also often targeted by the police through arrests and raids, and politicians pushed for laws to tame their performances on stage. As a queer woman who worked in burlesque, Zorita would have certainly been well aware of this. She also knew that she would likely be no stranger to a holding cell in Miami.17

At first, the passage of the Miami and Miami Beach ordinances legislated only against female impersonations, ignoring the fact that women could impersonate men too. The laws and anti-gay campaigns of the era more heavily focused on men, especially male effeminacy and gender nonconformity more broadly. The evidence suggests that local politicians and other people in power were less concerned—or perhaps even less aware—of lesbian intimacy and culture in the city. Although lawmakers eventually closed the loophole by also banning male impersonations, it appears that Zorita, as well as some other women entertainers, used the stage to poke fun of the absurd nature of laws that sought to regulate gender and sexual norms more broadly.

One of Zorita’s more popular acts has become known as her “half and half ” dance and striptease that shocked audiences with her attire, half of which was a woman’s wedding gown and the other half a man’s formal tuxedo. As both the bride and groom, she would consummate a marriage to herself on stage. It seems likely that Zorita would have performed this popular routine in both Miami and Miami Beach during years when antigay campaigns there targeted gender-bending performances on stage.18

Gender transgression was often at the center of Zorita’s private and public image. A cursory glimpse at Zorita’s personal photo albums reveals that she regularly attended social events with other women. While Zorita almost always presented herself dressed and styled in feminine attire, she was frequently seen accompanied by a masculine-presenting woman.19

Zorita’s inner circles regularly displayed the “femme” and “butch” pairings many came to associate with lesbian identity and culture by the mid-twentieth century. The stark contrast of the butch and her companion, the highly stylized, hyperfeminine “femme,” helped make lesbian identity and culture legible to others. As Alix Genter has argued, “Knowing that female masculinity was the public face of lesbianism, women played with queer visibility, keenly aware that the way they looked could have significant consequences—both positive and negative.” Women’s gender expressions—perhaps especially their dress and mannerisms or behaviors—could be adapted, as needed, to indicate their wants, desires, availability, status, power, transgression, and defiance.20

And it seems Zorita did just that. Columnists and reporters often speculated about Zorita’s romantic affairs with men, and yet she openly flaunted her affinity for butch women. In one image, likely from the mid-1950s, Zorita is seen with her hand resting on the lap of her female friend who went by the name “Gus.” Zorita’s mother, also in attendance, looks intently at the two women, whose highly stylized and nearly exaggerated gender presentations mark them as unmistakenly queer. Over the years, Zorita also cultivated an active circle of women lovers and friends, as well as gay male friends and colleagues. In later years, she would even welcome her audience at the club by saying, “Ladies and gentlemen and those under suspicion!”21

In 1964, she pushed gender norms even further by opening and managing her own burlesque club, Zorita’s Show Bar, located in the Sunny Isles area. Because she did this at a time when women did not have direct access to business loans or credit, she had to secure a male cosigner. Banking on her national reputation and her longtime experience in the business, she also knew to expect that her establishment would be regularly and unduly surveilled by law enforcement. She co-owned the bar with another woman. While this was reported in the press, the story did not mention—and the reporter likely did not know—that her business partner was her then-lover and romantic partner.22

Throughout the nation, the “lavender scare” linked the era’s antigay fervor with anticommunism and, in the South, these efforts were especially linked to anti-Blackness, including upholding racial segregation. In Florida, state lawmakers created an investigative committee in 1956 commonly referred to as the “Johns Committee” but officially named the Florida Legislative Investigation Committee. It was initially formed to stop and undo advances made in the name of Black civil rights in the state. Within a few years, however, the committee shifted most of its attention to attacking queer people and culture when it failed to provide ample evidence that Black civil rights organizations had been infiltrated by communists.23

Zorita and Miami’s Race Relations

At times, Zorita used her influence to speak out against racial segregation. In the early 1960s, she moved to the suburb-island of North Bay Village. By 1965, she had received complaints from several of her neighbors’ wives that their husbands were ogling her through the bushes. After all, she had a penchant for skinny-dipping. To further anger her white and prudish neighbors and attract media attention—something she had mastered over the years—she decided to defy yet another local ordinance: one that regulated lawn signs on people’s properties. These restrictions were intended to keep the neighborhood, which had a history of being “highly restricted,” for whites only. A year after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, Zorita placed a sign in her own front yard that read “For Sale: White or Colored.” She later told reporters, “I love people not for the color of their skin.”24

At least in her own club, Zorita performed to mixed audiences and hired Black and Latina performers and staff. An advertisement in the newspaper noted that Zorita’s Show Bar was looking to hire a “colored cocktail waitress” who could also possibly perform as a go-go dancer. It is important to note, however, that the ad qualified that the ideal candidate would be a “beautiful light skinned showgirl type.” The desirability for someone who is lighter skinned followed a decades-long trend to temper “exotic” representations in these spaces through the prism of whiteness. In making these decisions, Zorita seems to have been, at least partially, responding to customers’ interest in seeing women performers who they believed to be exotic, as hailing from a foreign place, or who were racialized in some other way. This included billing dancers such as “Mora from Jamaica” and “Peruvian Carmen.”25

Women of color in Miami’s burlesque scene navigated these spaces without the benefit of the white or class privilege that Zorita had. Evidence suggests that Black and Latina dancers and staff were no strangers to arrest and police harassment. The woman billed as “Mora from Jamaica” was named Mora J. Clark, and she, along with another woman named Rita Solero, was arrested at Zorita’s Show Bar by the county’s vice squad in 1969. Both were charged with soliciting for prostitution and soliciting for drinks. The following year, police raided the joint again, and several dancers and bartenders were arrested for either indecent exposure or soliciting drinks. Zorita, along with her co-owner and then-partner, Betty Ann Rielly, were also charged with allowing the solicitation of drinks.26

Zorita’s Story Reflects Miami’s

Zorita retired in earnest sometime in the late 1970s, a time when Miami’s LGBTQ culture and demographics were once again undergoing major transformation. Miami had become a battleground for the nation’s culture wars, including lesbian and gay rights. In 1977, Florida Orange Juice spokeswoman and gospel singer Anita Bryant fronted a campaign called “Save Our Children” to remove countywide legal protections in housing, employment, and public accommodations for lesbians, gays, and bisexuals. Zorita, who was then in her early sixties, referred to Bryant as a “simple bitch.” Bryant and her followers succeeded in stripping those legislative protections from local lesbians, gays, and bisexuals—protections they would not secure for another two decades (and far longer for transgender and gender-nonconforming people).27

Racial and ethnic tensions were also very high in the city. In 1980, an all-white jury acquitted four white police officers in the 1979 murder of a Black man named Arthur McDuffie, which culminated in a major rebellion in Miami, especially in Liberty City, a historic Black community. In the end, at least eighteen people died, and the city incurred over $80 million in damages. Meanwhile, new waves of immigrants, including many from Cuba, Haiti, Colombia, and Nicaragua, made their way to Miami during these years. The highly controversial Mariel boatlift of 1980, for example, which coincided with the McDuffie rebellion, brought roughly 125,000 Cubans, including a large contingent of highly profiled gay and gender-bending migrants, to the United States. Most of them settled in Miami. All this fueled the nation’s first major English-only movement, as Miami residents soundly voted in November of 1980 to undo the county’s bilingual and bicultural initiatives. If Miami was depicted as a fairyland in the early twentieth century and a playground for decades after that, reports and pundits now described it as a place of chaos, violence, corruption, and danger. A 1981 cover of Time magazine editorialized: “Paradise Lost?”28

By 1980, Zorita and her female partner of many years had left Miami. They moved a few counties north to Stuart, Florida, which had a slower-paced lifestyle and offered them a greater sense of security and relative obscurity. There, they bred Persian cats. They remained together until November 12, 2001, when Zorita died of a heart failure at the age of eighty-six.29

Zorita left an indelible mark on Miami’s history and in the hearts and minds of the thousands of people who traversed it. Her story helps reveal the complexities and multilayered meanings of race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and class in a New South city that is just “south of the South.” She carefully navigated post-war urban, racial, gender, and sexual anxieties—often to her advantage—in the midst of a Cold War that was felt very differently in a city just a few dozen miles from Cuba, the United States’ neighbor-turned-enemy. Zorita’s time in Miami reveals both the fragility and malleability of whiteness, femininity, queerness, and transgression. Her life and career in Miami reveal a different, and often neglected, story of the New South. It is among the many we have yet to fully understand or take seriously.30

Julio Capó Jr. is associate professor of history at Florida International University. He is the author of Welcome to Fairyland: Queer Miami before 1940, which received the Charles Sydnor award from the Southern Historical Association. He has curated several exhibitions, including Queer Miami: A History of LGBTQ Communities and Zorita Takes Miami.

The author thanks the incomparable Tawny Petillo, Zorita’s daughter, who shared her private archive with me. Tawny has done so much to preserve and share our community’s stories and has long since been a fierce advocate and agent for change. Thank you for being a friend (I had to find a way to include that) and ally. I am so grateful the universe brought us together.

Header image: Likely taken in the mid-1930s, this rare photograph features “Zorita and Her Queens of the Nude World,” one of the nudist carnival troupes she joined during the early years of her career. Based out of the San Francisco Bay area, these shows were attached to a controversial burlesque and pornographic impresario named Sint S. Millard. By this point, Zorita had already adopted her now-famous stage name and had become the main star and attraction. Courtesy of the Tawny Petillo Collection.

NOTES

- “Stripper, Snake Freed,” Miami Herald, April 2, 1960, 21.

- Juanita Greene, “Illegal Repairs Save Doomed Negro Shacks,” Miami Herald, April 2, 1960, 21; Rick Tuttle, “Cuban Bomb Wasn’t Political,” Miami Herald, April 2, 1960, 21; see N. D. B. Connolly, A World More Concrete: Real Estate and the Remaking of Jim Crow South Florida (University of Chicago Press, 2014); Raymond A. Mohl, South of the South: Jewish Activists and the Civil Rights Movement in Miami, 1945–1960 (University Press of Florida, 2004); also see María Cristina García, Havana USA: Cuban Exiles and Cuban Americans in South Florida, 1959–1994 (University of California Press, 1996).

- Elaine De Valle, “Zorita, 85, Well-Known Stripper Danced with Snakes,” Miami Herald, November 14, 2001; Jack McClintock, “Zorita: Memoirs of a Snake Dancer,” Tropic (Miami Herald Sunday Magazine), April 29, 1973; “Princess Zorida of Nudist Colony at Capitol Theater,” n.d., scrapbook clipping, Tawny Petillo Collection, Broward County, FL.

- “‘Back to Nature’ Picture Coming to Unique Vitaphone,” Santa Cruz Sentinel, February 9, 1936, 6.

- “500 Scramble as Girl Leads Snake on Leash,” Miami Herald, February 23, 1939, 13; advertisement for Minsky’s Burlesque, Miami News, February 26, 1939, 32.

- James O’Neill Jr., “Zorita’s Latest Tour-de-Force Shouldn’t Happen to a Snake,” Washington Daily News, October 10, 1950, 32.

- “At Home with Zorita,” Pictorial Movie Fun, May 1942, 5.

- “Characteristics of the Population of the Miami, Fla., Standard Metropolitan Area: April 1, 1950,” Bureau of the Census, Department of Commerce, April 18, 1951; Tawny Petillo, interview with author, February 24, 2024.

- Julio Capó Jr., Welcome to Fairyland: Queer Miami before 1940 (University of North Carolina Press, 2017), chaps. 2 and 3.

- “Club Klan Raided Closed Down After Sheriff’s Warning,” Miami Herald, November 17, 1937, 1; “La Paloma Ban Asked by State,” n.d., newspaper clipping, box 1, Robert R. Taylor Scrapbooks, HistoryMiami Museum, Miami, FL; Julio Capó Jr., “Sexual Connections: Queers and Competing Tourist Markets in Miami and the Caribbean, 1920–1940,” Radical History Review no. 129 (October 2017): 9–33.

- John B. McDermott, “Male Strip-Tease Act Too Raw,” St. Petersburg Times, March 24, 1944, 13; also see Capó, “Sexual Connections.”

- Capó, Welcome to Fairyland, chap. 7.

- “Club Klan Raided,” 1.

- See Rosalie Schwartz, Pleasure Island: Tourism and Temptation in Cuba (University of Nebraska Press, 1997).

- Robert M. Levine and Moisés Asís, Cuban Miami (Rutgers University Press, 2000), 21.

- Advertisement for Zorita Presents Cuban Circus Revue at Gaiety Club, Miami News, May 15, 1955; original Script for “The Schooner Bay Caper,” Tawny Petillo Collection, Broward County, FL.

- David K. Johnson, The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government(University of Chicago Press, 2004); William N. Eskridge Jr., “Privacy Jurisprudence and the Apartheid of the Closet, 1941–1961,” Florida State University Law Review 24, no. 4 (Summer 1997): 829; also see Julio Capó Jr., “‘It’s Not Queer to Be Gay’: Miami and the Emergence of the Gay Rights Movement, 1945–1995” (PhD diss., Florida International University, 2011).

- Miscellaneous photographs by Murray Korman, n.d., Tawny Petillo Collection, Broward County, FL.

- Miscellaneous photographs, n.d., Tawny Petillo Collection, Broward County, FL.

- Alix Genter, “Appearances Can Be Deceiving: Butch-Femme Fashion and Queer Legibility in New York City, 1945–1969,” Feminist Studies 42, no. 3 (2016): 631; also see Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy and Madeline D. Davis, Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold: The History of a Lesbian Community, 2nd ed. (Routledge, 2014).

- McClintock, “Zorita: Memoirs of a Snake Dancer,” 40.

- Tawny Petillo, interview with author, February 24, 2024.

- Stacy Braukman, Communists and Perverts Under the Palms: The Johns Committee in Florida, 1956–1965 (University Press of Florida, 2012); James A. Schnur, “Closet Crusaders: The Johns Committee and Homophobia, 1956–1965,” in Carryin’ On in the Lesbian and Gay South, ed. John Howard (New York University Press, 1997), 132–163.

- Listing for North Bay Island Property, Miami News, February 9, 1945, 19. Also see Rafael Lorente, “The Many Incarnations of North Bay Village,” Miami Herald, April 27, 1995; Miller Davis, “Snake-Charmer Zorita Feuds with Neighbors,” Miami Herald, October 22, 1965.

- Job Advertisement for Zorita’s Show Bar, Miami Herald, August 7, 1965; miscellaneous flyers and advertisements, n.d., Tawny Petillo Collection, Broward County, FL.

- “3 Dancers Acquitted,” Miami Herald, October 18, 1969, 31; “Zorita and Friends Nabbed for Exposure,” Miami News, August 14, 1970, 6.

- Tawny Petillo, interview with author, March 27, 2024.

- James Kelly, “South Florida: Trouble in Paradise,” Time, November 23, 1981. See Capó, “‘It’s Not Queer to Be Gay.’”

- De Valle, “Zorita, 85, Well-Known Stripper Danced with Snakes.” The local newspaper seems to have erred in reporting her age at death as eighty-five. This is not surprising considering Zorita regularly gave false information about her age and scolded reporters who dared to ask her. Tawny Petillo, interview with author, February 24, 2024.

- Mohl, South of the South.