In the heat of an Atlanta summer evening, the ALFA Omegas softball team took the field at Iverson Park. As an out-lesbian team organized by the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance (ALFA), they were different from other softball lineups in the City League in 1974. The Omegas brought together ALFA members at varying skill levels—neophytes and practiced athletes alike. At the mound was Lorraine Fontana, who had never pitched or played before that summer. At first base, Charlotte Harper: one of ALFA’s two player-managers, a power hitter and leader on the diamond. She had been playing the game since her father cleared pine trees behind her South Carolina childhood home and built a baseball field for kids in her Black neighborhood. Lunging across second base was Vicki Gabriner, a self-described “skinny Jewish kid from Brooklyn” who shied away from sports. From the bleachers, excited teammates shouted out cheers: “Give me an A-A, give me an L-L, give me an F-F, give me an A-A! Whattaya got? Dykes, dykes, dykes!”1

The ALFA Omegas brought their anti-hierarchy feminist politic to softball. They decided on rosters collectively and gave all players equal time on the field. This egalitarian strategy surprised everyone, especially when the ALFA Omegas made it to the league championship game in 1974, two years after ALFA’s founding. Although they did not win, they showed teams like the Stumps, the Bankhead Panthers, and the Southern Bell Rams, which often had male coaches and whose players did not advertise their sexuality, a new way of playing and being out. ALFA expanded their softball teams in 1975 and continued to participate in public life as an out-lesbian organization and out-team. They were proud of their first season not only as an athletic accomplishment but also for the way they had connected political organizing and recreational sports.

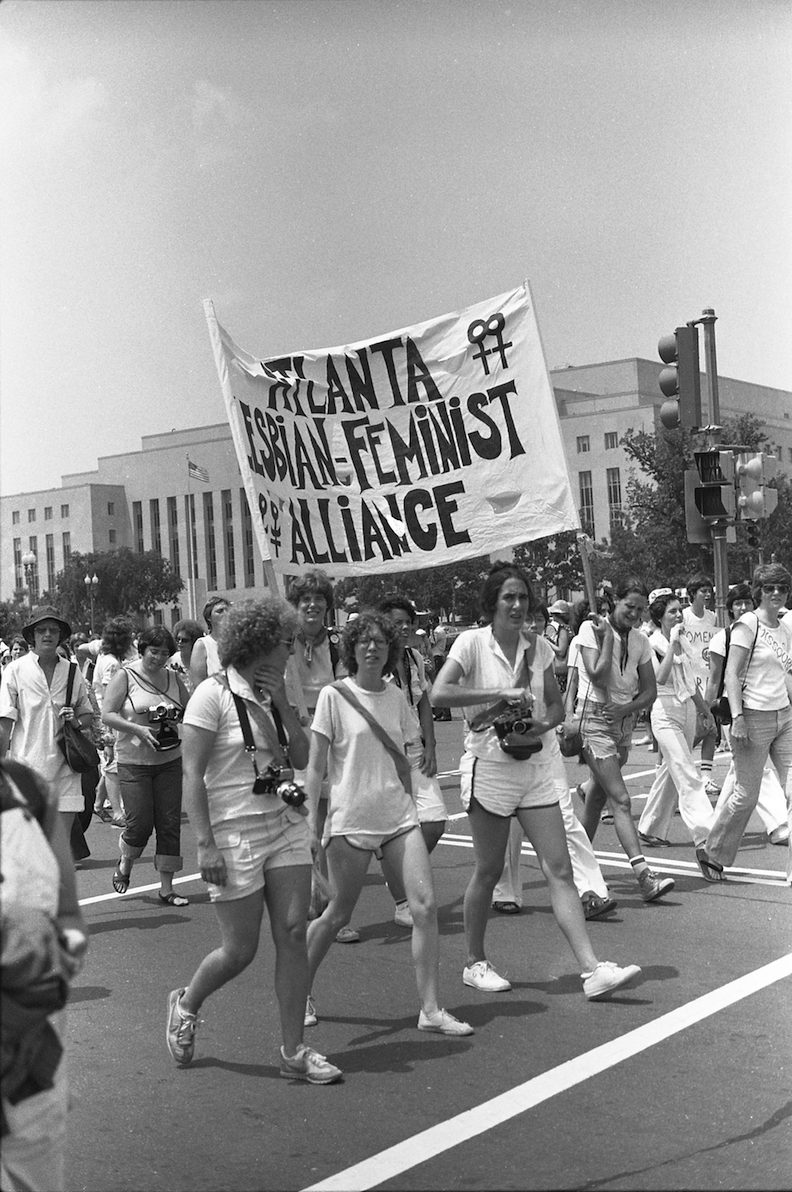

Noting a lack of inclusion in both gay and feminist spaces in Atlanta, lesbian activists in a June 23, 1972 meeting articulated the need for an organization that was distinctly lesbian and feminist. And so ALFA began. “A big part of ALFA was people finding each other,” Lorraine Fontana recalled. For the next twenty years, ALFA served as a cultural and political umbrella group for lesbians of Atlanta’s Little Five Points neighborhood. While the organization has a long and winding history, the politics of ALFA in its inception, from 1972 to 1975, offer a critical window into how lesbian feminists were envisioning political organizing, coalition building, and sports in the New South. With backgrounds in antiwar activism, socialism, and civil rights work, the women who formed ALFA brought complex analyses of power to organizing and creative approaches to confronting sexist, racist, and homophobic institutions. They challenged media coverage of gay life, planned marches to pass the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), and utilized radical strategies in recreational softball. Members saw lesbian feminism as an exciting avenue for political engagement, they understood lesbian spaces to be crucial locations to gather, and they envisioned recreation as a tool for expanding the reach of their activism. Atlanta offers a particularly rich history as a distinct hub of the New South where activists with a wide range of antiwar and civil rights experience came together, came out, and looked to shift feminist frames.2

Lesbians on the Move

While lesbian feminism is often placed apart from New Left organizing, ALFA’s founding demonstrates that such movements overlapped in nuanced ways. The New Left of the 1960s was a constellation of movements for free speech and civil rights and against war, imperialism, and the “Establishment.” In Little Five Points, many lesbian activists “came out” of those Left politics. New arrivals in Atlanta with experience in antiwar organizing, such as Vicki and Lorraine, who both moved to the city in 1970, quickly found an outlet for activism within the emergent radical paper The Great Speckled Bird. In 1968, Emory University antiwar activists had founded the Bird, as it was known, as a countercultural newspaper. Women at the Bird quickly became frustrated with gender roles at the paper. Men edited, wrote, and coordinated business. Women typed, opened mail, and lacked editorial power. As Becky Hamilton, one of the original Bird staffers, wrote, “A woman’s caucus of the Bird was formed because we need each other.” In 1969, the caucus demanded full salaries, a women’s issue, and oversight of the paper’s often sexist advertisements. Women began to write and put their struggles on the page. Pushing this activist work forward, many caucus members created Atlanta Women’s Liberation in 1970. These emergent feminists were from Georgia, Tennessee, as well as northern states.3

In the early 1970s, Little Five Points was a hub of hippie, leftist, and lesbian life. Charlotte remembered the neighborhood, just northeast from downtown, and nearby Candler Park as walkable, rundown, and affordable for its residents. To support each other, feminists who lived in Little Five Points created group houses and food buying clubs, which collectively bought and distributed bulk goods. Many organized with the Bird Women’s Caucus, Atlanta Women’s Liberation, and Gay Liberation Front. Yet, feminists soon decided it was necessary to form their own organization. Remembering those early days, Vicki said, “We were at a point in our lives where we . . . needed to have lesbian space. We need to attend to our own needs.” After initial meetings, the group announced its foundation in the Bird ’s August 1972 issue. The article “Lesbians on the Move” was both an invitation and a declaration:

We are a political action group of gay sisters. We are the large coordinating group for smaller consciousness raising groups and an umbrella group for Women’s projects and gay Women’s projects. We will serve as a communications center for all these groups. We intend to provide alternatives for ourselves and all sisters that will free Women to live outside sexist culture. We aim to reeducate the non-homosexual community, society in general, by being visible and vocal at every opportunity. We aim to reach out to all sisters in order to establish solidarity. We intend to work with gay brothers to further our mutual goals of gay liberation. We intend to initiate demonstrations and public actions to emphasize our demands.

ALFA focused on the political power of being out and the need for gay women’s spaces. It saw itself as coalitional, visible, and intent on supporting gay men, straight feminists, political allies, and broader publics. It recognized that its original cohort was mostly white and it sought to build a platform that was anti-racist, anti-imperialist, and open to non-lesbians. ALFA founders stressed that “no lesbian id card” would be required.4

By the fall, ALFA was back in the Bird. The paper’s women’s issue advertised an open house at the ALFA headquarters on Mansfield Street. In a full-page spread, Lorraine described ALFA’s vision for a library and softball team and invited readers to the ALFA house. Lorraine and others living in a lesbian house called Edge of Night granted use of the communal space for ALFA meetings. Thus, the ALFA house was born. The two-story Craftsman home had a front porch and large magnolia tree in the front yard. Inside, a poster of Angela Davis graced a large wooden table and lesbian art by photographer Marcelina Martin hung above comfortable couches. Some ALFA members lived upstairs and meetings were held downstairs. Located just off the main drag on Moreland Avenue, the house quickly became a focal point of a network of lesbian communal houses in the neighborhood, with names such as Marmalade Manor, Tacky Tower, and Ruby Fruit Jungle. Humor and creativity were central tools for ALFA and its gay grid in Little Five Points. The ALFA house was a space of organizing as well as a location for the organization’s growing resource archive, which predates other installments of radical archiving such as the Lesbian Herstory Archive, which New Yorker Joan Nestle founded in 1974.5

ALFA members were in constant conversation with Atlanta newspaper editors from the Bird to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution about characterizations of gay and lesbian life and the continual lack of representation. ALFA also made this a national conversation when they wrote a letter to Ms. magazine in 1972 calling for the publication to cover lesbian issues. Though staff, contributors, and readers successfully pushed the Bird and Ms. magazine to report on lesbian and gay subjects, the mainstream press remained a tool of gay oppression. When Atlanta police arrested gay men in public stakeouts, newspapers printed the arrestees’ names and addresses. ALFA and Gay Liberation Front pressured editors for representation and, in 1973, took action. Members picketed local newspapers for ignoring gay and lesbian events and began printing and distributing the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance Newsletter (later called Atalanta). Through protest and print media,ALFA attacked invisibility with spatial strategies. They entered residential homes through Atalanta and editorial writing and engaged civic space by picketing downtown, creating T-shirts, and inviting the public to open house events.6

1974: The Year of the Rabble

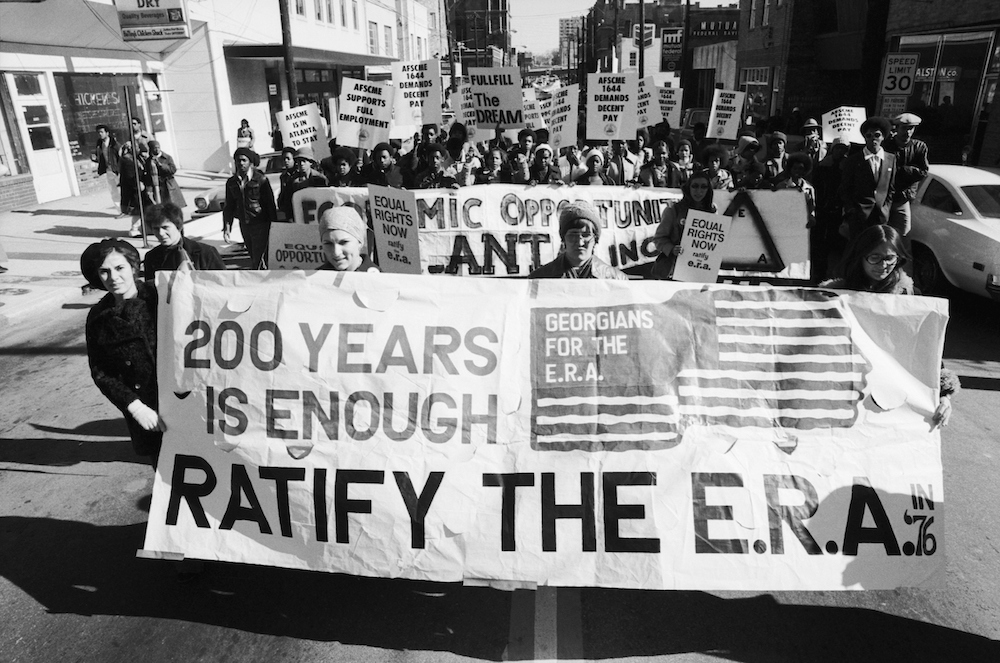

ALFA members brought these strategies to the ERA. On March 22, 1972, the US Senate voted to pass the ERA (84-8) and the amendment was sent to states for ratification. If thirty-eight states ratified the bill, it would become national law. ALFA members Vicki and Cheryl, who worked on WRFG’s women’s radio show, started attending era coalition meetings. Georgia’s coalition included the League of Women Voters, American Association of University Women (AAUW), Churchwomen United, National Organization for Women (NOW), Georgia Women’s Political Caucus (GWPC), and the Governor’s Commission on the Status of Women (GCSW). Looking back on these feminist coalitions, Vicki recalled the internal tensions of initial meetings:

We were both fascinated and intimidated to find ourselves in meetings with women who had been politically active for twenty and thirty years. I was excited by the possibility of a mutual exchange of ideas, although the excitement was not shared by most members of the coalition. There was not much receptivity to the dungarees, no make-up, impatience, and unconscious casualness which is a part of my counterculture style. Nor was anyone too happy about my lesbianism.

ALFA members were aware of how their worldview and sexuality were a challenge for members of more conservative organizations. In 1970, this coalition of Georgia women’s organizations had just succeeded in campaigning Georgia legislators to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment (fifty years after women’s suffrage was enacted). Women from organizations such as the AAUW, GWPC, and the League of Women Voters were versed in state politics and well positioned to lobby for ERA ratification, which their more conservative members considered the only viable pathway to pass the ERA.7

Seeking a more activist approach, ALFA women and members of the Socialist Worker’s Party (SWP) chose to launch their own organization, Georgians for the ERA (G-ERA), in May 1973. G-ERA remained in coalition with existing networks, but argued it was important to be out in political work. Its membership did not want to closet their politics, whether radical, socialist, or lesbian-identified. It was also important for ALFA activists to bring era struggles directly to the public space rather than rely on lobbying alone. While they valued the organizing history represented by NOW and the League of Women Voters, they were equally aware of substantial barriers to coalition.

By 1974, the ERA was ratified in thirty states. With only eight states pending and Georgia’s legislative session approaching, Georgians for the era decided to organize a march for January 1974 and began coalition building. The first meeting included NOW, Georgia Nurse Association, Black Women’s Coalition, Feminist Action Alliance, Communication Workers of America, SWP, and student groups. G-ERA invited Gloria Steinem to speak at the march and she accepted. When the larger ERA network learned of the planned march and invited speaker, many responded that they could not support a public protest under any circumstances. Churchwomen United and AAUW would support a march, but not with the presence of lesbian feminists and socialists. Without Churchwomen United and AAUW, G-ERA pivoted the march into a parade and they asked Eléonore Raoul, an eighty-seven-year-old suffragist, to lead it. In 1915, Raoul had led a pro-suffrage march of five hundred women down the streets of Atlanta on horseback. After accepting the invitation, Steinem received letters from conservative women concerned her presence would alienate legislators. Steinem rescinded her offer to speak because of the pressure, although she wrote a letter stating she disagreed with the exclusion of “unpopular” women (lesbians and socialists). After a number of letters between the G-ERA and Steinem, she agreed to meet privately with the two camps of Atlanta ERA organizers. While radicals and conservatives came together to meet Steinem, no one changed their position. Some labor groups no longer endorsed the parade after Steinem pulled out, but Georgia Nurses Association and United Auto Workers (UAW) stuck it out, despite the potential liability of working with radical lesbians. NOW also remained a strong ally.8

Despite or because of Steinem’s highly politicized absence, there was a large turnout. On January 12, 1974, Raoul led the Saturday parade of over a thousand marchers in a 1930s open touring car. As they marched through Atlanta, the G-ERA organizers realized they were leading the largest political demonstration for women’s rights in the city’s history. “The energy was high,” Vicki wrote of that day. “Not only had socialists and lesbians not destroyed the march, they had gotten out many of the people who were in it.” G-ERA speakers told the excited crowd that the ERA was for all women. According to Vicki, “Like the call for abortion on demand, black civil rights, or potential action to repeal sodomy laws, the ERA is an important component of a massive social movement to change the conditions in which we live.” The organizers of the march drove home the idea that the amendment was a part of a long history for women’s rights and an issue of import to women beyond established women’s organizations or lobbying efforts. Yet, the festive mood of the parade was short-lived.9

The following week, G-ERA organizers attended the vote in the Georgia House and watched as the proposed ratification was roundly defeated, 104–70. While the ERA had bipartisan support when the US Senate passed it in 1972, right-wing grassroots organizing quickly eroded ERA’s Republican support. Despite their disappointment, however, the G-ERA continued to organize, march, and write. They created a newsletter and sharpened their analysis of ERA’s importance to unions and women of color. In 1975, three thousand people turned out for the ERA march. Still, the amendment remained unratified in Georgia and many people boycotted businesses in the state. When the Third Annual Southeastern Conference of Lesbians and Gays met in Atlanta in 1978, ALFA members and conference organizers alerted attendees to pro-ERA local businesses; this tactic allowed gay and lesbian activists to respect the boycott while attending the conference and turned businesses into sites of political education and mobilization. By 1978, Georgia activists had been fighting for the ERA’s ratification for six years, and momentum was beginning to decline.10

The amendment was never ratified in Georgia. New Right activism, driven by Phyllis Schlafly’s STOP ERA (Stop Taking Our Privileges) movement and based in renewed Christian conservatism, pushed Republican legislators away from the amendment’s passage and reframed the ERA as a bad move for women. Schlafly warned the public that the ERA would force women to enter Selective Service, create unisex bathrooms, and remove spousal (“dependent wife”) benefits. She also deemed the amendment the “Pro-Gay ERA,” a threat to the straight nuclear family. Kathryn Dunaway, leader of Georgia’s STOP ERA committee, echoed Schlafly’s omens in regular meetings with local legislators. Her committee highlighted the involvement of gay organizers in ERA activism. Demonstrating their dedication to traditional gender roles, Dunaway’s coterie baked bread for lawmakers with the attached note: “From the breadmakers to the breadwinners.”11

The ALFA Omegas

After ERA organizing in the winter of 1974, and with the next legislative session a year away, ALFA activists looked to new avenues of public engagement. The organization decided to create an out-lesbian, racially integrated softball team and enter the City League. Lorraine remembered long conversations over the team name, the ALFA Omegas. Playing in parks throughout Atlanta, the team gained visibility and in turn ALFA’s activist organization grew. They were “saying it,” not just “playing it,” historian A. Finn Enke distinguishes. “Softball in public parks was an activity and a location through which a wide range of political activisms took place.” For spectators and players, many of whom were lesbian-identified but not “saying it,” this was a new way of being in civic space—parks were not apolitical, but important places for movement building.12

ALFA hollered gay cheers and eschewed competitive norms. They rotated players equally, which allowed Vicki, who was in her own words “by no means a jock,” a place on the field. As a player-manager, Charlotte taught her teammates how to play and wrote team updates in ALFA’s newsletter. The ALFA Omegas did not have a male coach like other teams, instead creating the player-manager role in an effort to be truly egalitarian. In our interview, Charlotte remembered, “We didn’t do too badly. We ended up with two teams. We had ALFA 1 and ALFA 2, because there were so many people who wanted to be involved. So it became a big thing. It was a good way of actually marketing the organization. Because we would have games every week and . . . it gave us an avenue to socialize after the games.”13

After wins and losses, teams went to the Tower Lounge—a straight working-class bar during the week and a dyke bar on the weekends—or back to the ALFA house. As Vicki put it, “I’m not a drinker, but at certain points that was really where lesbian space was, in the bars. Very early women’s music concerts were in the bars and we always went there after the game.” ALFA’s presence at bars, on fields, and in ERA marches elevated the organization’s status, increasing its profile in Atlanta. As a part of their politics of visibility, ALFA saw softball as a political strategy and, as Charlotte noted, a way to build membership. After the summer of 1974, ALFA membership grew from thirty to one hundred.14

ALFA activism encompassed commonly understood political organizing and what is sometimes dismissed as “cultural feminism”—attention to media representation, communal living, and softball. While outside of the political establishment, cultural feminism offers an experience of liberation all its own. “We ran onto the field, most of us with our hairy legs and hairy armpits, sweating in the sun, exercising our muscles,” Vicki recalled in her 1976 article, “Come Out Slugging!” For jocks and non-jocks alike, playing softball was a way to connect to their physicality. Vicki wrote that “softball made us feel more powerful because we were learning to use our bodies as physical instruments.” ALFA’s softball strategy was an embodied form of activism.15

Athletics as an expression of female agency was in line with the movements for women’s physical culture in the US after Title IX’s passage. In 1972, tennis star Billie Jean King was named Sportswoman of the Year and shortly thereafter prevailed in the nationally televised “Battle of the Sexes” match against Bobby Riggs. The Women’s Professional Softball League formed in 1975, and the 1977 International Women’s Year conference in Houston included a torch run from Seneca Falls to Texas that passed through Georgia. For feminists nationwide, activity and sports were exciting forms of resistance, camaraderie, and personal growth. Harnessing this energy, softball in particular became an organizing tool for lesbian feminists across the South. Out-teams sprung up in cities such as Memphis, Tennessee; Lexington, Kentucky; Columbia, South Carolina; and Athens, Georgia. In Memphis, NOW formed a softball team as part of organizing efforts to ratify the ERA, creating an opportunity to meet new friends and build an activist network. But softball also raised tensions. Historians Stephanie Gilmore and Elizabeth Kaminski chronicle how the creation of the popular now softball team “with its suggestion of informal lesbian solidarity” caused friction within Memphis now in the late 1970s. While now showed support for lesbian members in the mid-1970s, by the end of the decade, rising right-wing Christian rhetoric in Memphis began to impact the organization. In 1982, NOW split over the “softball” issue. Softball became a euphemism for lesbian presence in NOW, as conservative members increasingly expressed distress that attention to gay issues detracted from the organization’s mission to support “family, women’s safety, and the era.” For ALFA Omegas, softball was a way to be out and release stress from closeted work environments and tension-riddled coalitions.16

ALFA’s team transformed the City League and was changed in turn by interactions with league players. While ALFA members lauded themselves for demonstrating how out and non-hierarchical a team could be, they still learned from seasoned players. Enke writes that “women of an established working-class softball culture inspired and challenged self-identified feminists.” At the Tower Lounge, Vicki remembers women “who had been lesbian in the 1950s and ’60s, who had come up through the school of hard knocks of lesbian life. As I met this group of lesbian southerners, I was very drawn to all of them, feeling that each of them had a piece of history that helped me to understand the world I was entering.” The exchange was two-way and often crossed generation and class lines. For the weekend regulars at the Tower Lounge the influx of ALFA players and friends brought new energy. Elizabeth Knowlton, an ALFA archivist and Omega votary recalled, “We didn’t have many public places. The Tower Lounge was really important to us. What we found out very soon in the women’s movement was that if you had a critical mass, you changed the space. At ALFA, we did everything in a mass!” For older lesbians, the post-game softball crowd offered an opportunity to teach as well as learn about activism in the city. Whether at the bar or on the field, ALFA impacted lesbian spaces by being out and putting forth a feminist politic.17

The Great Southeast Lesbian Conference

With larger membership following softball, ALFA decided to host a conference of southern lesbians in 1975. Without money to rent conference space, ALFA held sessions in lesbian houses around Little Five Points. Three hundred attendees from Florida, the Carolinas, Mississippi, Louisiana, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, Alabama, Michigan, Illinois, New York, DC, and Jamaica arrived for the two-day conference in late May. Participants included Minnie Bruce Pratt, a poet and activist from North Carolina, and Charlotte Bunch, a writer and organizer of the Furies Collective in Washington, DC. Attendees traversed the neighborhood and sat in living rooms for panels. The Great Southeast Lesbian Conference’s theme was “Building Our Community,” with the goal of improving communication throughout the Southeast during a weekend of workshops, music, and food. As the organizing committee reported back, “People in the rest of the country seem to think that nothing is going on down here, but the May weekend certainly gave the lie to that.”18

The event began on a sour note when five North Carolina women were arrested at a diner on their way to the conference. The diner was recommended as gay-friendly, but an off-duty cop escalated a bill dispute and arrested all five women while hurling homophobic slurs. Being out in public quickly became a liability for this group, and much of the conference was spent raising bail and legal funds. The Red Dyke Theater held a fundraising performance to generate bail money, and the owners of the Tower Lounge agreed to match any funds ALFA raised. Vicki believed that “softball was responsible for that solidarity.”ALFA players and fans had built solid relationships with Tower Lounge owners over the summer. Within a day, ALFA and conference goers were able to pay bail ($1,100 per arrestee) and the prosecution dropped all charges soon after.19

The conference advocated for cultivating out-lesbian community through creative means. Minnie Bruce Pratt remembered traveling “porch to porch” across the vibrant network of lesbian houses in Atlanta before returning to the ALFA house, the conference headquarters.

At night . . . we went to one of the theaters in the Little Five Points area. . . . There were about 300 lesbians in this theater. Before the entertainment started, we were all singing, “I’ve been cheated, been mistreated, when will I be loved.” And then the entertainment was . . . a lesbian feminist drag show with a butch and a femme.

While the conference focused on political issues such as FBI surveillance, it ensured plenty of time for entertainment and conversations on porches. For Pratt the drag show, with its tuxedos and leather, was just as valuable as workshops.20

On day two, the committee added three workshops by attendee request: “FBI Harassment of the Lesbian Community,” “Socialist Feminist Workshop,” and “Racism in the Lesbian Community.” In the latter, attendees shared experiences of racism in their respective communities and concluded that they would address racism through campaigns for women’s issues, such as the passage of the ERA; the defense of Joan Little; abortion, health care, and employment advocacy; and the availability of rape crisis centers and credit unions. The workshop addressed racism in lesbian life, but its late addition betrayed a lack of attention to experiences of lesbians of color. Historian La Shonda Mims notes that “while the predominately white conference attendees recognized separatism and racism as substantial issues, they grappled with the normative and troublesome assumption that African American women would simply join the lesbian-feminist movement, rather than the movement ‘expanding to include’ the needs and desires of African American women.” Lesbian and feminist-identified spaces, constructed with assumptions of race, gender, class, and sexuality, limited who was read as lesbian, feminist, and female. This led many Black lesbian activists to create spaces outside white-dominated organizations. Charlotte Harper went on to form Lesbians of Color/Lesbianas de Color (LOC) in Los Angeles when she moved there in 1976. LOC also utilized softball as an organizing tool to become LA’s most active out-lesbian of color organization in the late 1970s and early 1980s with additional chapters in San Diego and San Francisco. For attendees of the Great Southeast Lesbian Conference, the moment marked strengthened connections across the lesbian South with discussions and drag performances outlining exciting new sexual politics.21

From 1972 to 1975, ALFA navigated coalitional engagement with feminists, gay organizations, and social justice work in Atlanta, while incorporating elements of cultural feminism. ALFA was a location for meetings and rap groups, and for making cultural products and collecting lesbian print media. Such activities utilized the home, a domestic zone often ascribed to women, as a space of organizing. These public/private overlaps extended to the Little Five Points neighborhood, where ALFA women ran into each other in the course of their days. Moreland Avenue businesses became places for conversations about relationships as well as era marches. Parks became locations for lesbian feminism to have a presence and shout lesbian cheers. Playing all over Atlanta, ALFA’s visibility extended beyond left-leaning neighborhoods. ALFA activists brought organizing experience from civil rights and antiwar activities. They saw media as a vital avenue for engagement. Newspapers and newsletters entered homes and offered connectivity between rural and urban queer life. Through letters and picket lines, ALFA members pushed alternative and mainstream media to circulate lesbian lived experiences. Produced through engagement with contested spaces, lesbian activism was a critical component of feminist organizing in the Southeast in the 1970s.

Within the conferences and gatherings where lesbian activists debated and defined revolutionary ideas, concepts of being out in public and analyzing power through a feminist lens took shape, and ALFA’s history of organizing contains the seeds of today’s activism, outreach, and queer feminist visibility. The group pushed for coalitional engagement and a multipronged approach to activism. It was critical to have fun, to play sports, to participate in city park life, and it was equally important to create private and public lesbian-feminist spaces, to push for legislation, and to create radical archives. For queer activists in the twenty-first century, these historical roots of 1970s lesbian life resonate deeply. For me, as a “jock” and queer historian, I know my life was shaped by such grassroots efforts. I grew up in the Title IX era—as a tomboy in Little League and later as an awkward teenage girl who felt a little less awkward on the softball field. All this history winds its way to us—and through us. By documenting 1970s queer activism in Atlanta, my hope is that future activists will find points of connection, creative ideas about organizing, and insights into the role of sexuality in everyday life then and now.

This article first appeared in the Women’s Issue (vol. 26, no. 3: Fall 2020).

Rachel Gelfand is a postdoctoral scholar in the Department of American Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her interdisciplinary book project, Nobody’s Baby: Queer Intergenerational Memory and Methods, applies a queer analysis to modes of memory transmission and examines oral history, archives, and visual art.NOTES

- Charlotte Harper (pseudonym), in discussion with the author, December 5, 2017; Vicki Gabriner, “How a Skinny Jewish Kid from Brooklyn Found Happiness on the ALFA Omega Softball Team,” Great Speckled Bird, March 6, 1975, 15; Lorraine Fontana, in discussion with the author, February 22, 2015.

- Fontana, discussion. My relationship with alfa cofounder Vicki Gabriner inspired this project. Vicki was an integral member of my lesbian mothers’ community in Boston and, as a queer historian, I was eager to learn about her time in Atlanta. We devised a method of oral history interviewing over documents. Together, we studied in the alfa Archives at Duke University and her personal papers at her house. I have written about our queer intergenerational collaboration for Radical History Review. Additionally, I conducted traditional oral histories with Vicki, Lorraine Fontana, and Charlotte Harper. I am grateful for their insights and editorial contributions.

- Vicki worked on Black voter registration campaigns in West Tennessee in the mid-1960s, joined the Weather Collective from 1969 to 1970, and participated in the Second Venceremos Brigade to Cuba. Sally Gabb was a student activist at Duke University in the mid-1960s and participated in North Carolina sit-ins. Lorraine was an antiwar activist in New York before moving to Atlanta in 1970 to participate in antipoverty initiatives in Atlanta’s West End. Elaine Kolb, who hailed from a small town in Western New York and became politically active at the University of Buffalo, joined the Third Venceremos Brigade. Organized by Students for a Democratic Society and Weathermen, the Brigades brought US volunteers to newly socialist Cuba to help in the sugar harvest. It was on the Brigade that Vicki met Atlanta feminists and decided to move to the city. Becky Hamilton, “Even a Woman Can Do It: Bird Women’s Caucus,” Great Speckled Bird, October 11, 1970, 3; Sally Gabb, “A Fowl in the Vortices of Consciousness: The Birth of the Great Speckled Bird,” in Insider Histories of the Vietnam Era Underground Press, part 1, Voices from the Underground, ed. Ken Wachsberger (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2011), 94.

- Sally wrote of Bird staff: “We were stridently ‘freaks’”; see Gabb, “A Fowl in the Vortices,” 94. Large houses were cheap to rent as a result of white flight and urban renewal. The historic African American community of Rose Hill was pushed out by the city through the expansion of Candler Park in the 1920s and city ordinances in the 1940s. For more on Rose Hill history, see “Early Edgewood-Chandler Park BiRacial History project,” Old Stone Church BiRacial History Project, updated June 1, 2013, http://www.biracialhistoryproject.org/RoseHillMarker.html. One buying club in Little Five Points became Sevananda Co-op in 1974; see Fontana, discussion; Vicki Gabriner, interview by author, March 8, 2014, interview U-1072, Southern Oral History Program Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; “Lesbians on the Move,” Great Speckled Bird, August 21, 1972, 15; Lorraine Fontana quoted in James T. Sears, Rebels, Rubyfruit, and Rhinestones: Queering Space in the Stonewall South (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2001), 110.

- Lorraine Fontana, “ALFA House Open,” Great Speckled Bird, October 9, 1972. A lesbian house in Little Five Points called Ruby Fruit Jungle predates the famous novel by Rita Mae Brown. Lorraine explained that a child living in the house came up with the name and Rita Mae Brown visited prior to writing her book; Lorraine Fontana, in discussion with the author, February 23, 2015; Elizabeth Knowlton, “How to Start a Lesbian-Feminist Organization (Or Any Kind of Non-Hierarchical Group),” 1984, box 1, file 19, ALFA Archives, Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture, Duke University.

- Letter to Ms. magazine, 1972, box 1, file 19, ALFA Archives. In what the media dubbed the Atlanta Public Library Perversion Case of 1953, the city’s two papers printed names of the gay arrestees six times. John Howard, “The Library, the Park, and the Pervert: Public Space and Homosexual Encounter in Post-World War II Atlanta,” Radical History Review 62 (1995): 166–187.

- GCSW was a multiracial, multi-class organization led by veteran civil rights organizers. Jennifer P. Gonzalez, “Searching for Sisterhood: Black Women, Race and the Georgia ERA,” unpublished thesis, 2006; Vicki Gabriner, “ERA: The Year of the Rabble,” Quest: A Feminist Quarterly 1, no. 2 (Fall 1974): 65.

- Gabriner, “ERA,” 67, 69.

- Gabriner, “ERA,” 70, 63.

- For ERA state histories, see: Megan Taylor Shockley, Creating a Progressive Commonwealth: Women Activists, Feminism, and the Politics of Social Change in Virginia, 1970s–2000s (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2018); Erin M. Kempker “Coalition and Control: Hoosier Feminists and the Equal Rights Amendment,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women’s Studies 34, no. 2 (May 2013): 52–82; Judith Ezekiel, Feminism in the Heartland (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2002); and Stephanie Gilmore, “The Dynamics of Second-Wave Feminist Activism in Memphis, 1971–1982: Rethinking the Liberal/Radical Divide,” NWSA Journal 15, no. 1 (2003): 94–117. For scholarship on ERA at the national level, see: Jane J. Mansbridge, Why We Lost the ERA (University of Chicago Press, 1986); Katherine Turk, Equality on Trial: Gender and Rights in the Modern American Workplace (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016); Mary Frances Berry, Why ERA Failed: Politics, Women’s Rights and the Amending Process of the Constitution (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988); and Stephanie Gilmore, ed., Feminist Coalitions: Historical Perspectives on Second-Wave Feminism in the United States (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008). See also: Vicki Gabriner, “Southeastern Conference of Lesbian and Gay Men, Atalanta, May 1978.

- For more on Georgia’s (non)ratification, see “Georgia,” Equal Means Equal, accessed July 10, 2020, https://equalmeansequal.org/states/georgia/. A Maine STOP newspaper advertisement succinctly broke down fears concerning gender, sexuality, and childhood: “What does the word ‘sex’ mean? The sex you are, male or female or the sex you engage in, homosexual, bisexual, heterosexual, sex with children . . . or whatever? Militant homosexuals from all over America have made the ERA issue a hot priority. Why? To be able finally to get homosexual marriage licenses, to adopt children and raise them to emulate their homosexual ‘parents,’ and to obtain pension and medical benefits for odd-couple ‘spouses.’ . . . Vote NO on 6! The Pro-Gay ERA.” Phil Tiemeyer, Plane Queer: Labor, Sexuality, and AIDS in the History of Male Flight Attendants (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 115.

- A. Finn Enke, Finding the Movement: Sexuality, Contested Space, and Feminist Activism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 147, 18.

- Vicki Gabriner, in discussion with the author, June 2014.

- Gabriner, SOHP interview.

- Vicki Gabriner, “Come Out Slugging!,” Quest: A Feminist Quarterly 2, no. 3 (Winter 1976): 54, 55.

- Susan Ware, Game, Set, Match: Billie Jean King and the Revolution in Women’s Sports (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 9. For lesbian feminist softball, see Pat Griffin, “Diamonds, Dykes, and Double Plays,” in Sportsdykes: Stories from on and off the Field, ed. Susan Fox Rogers (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1994), 191–201; and Jacqueline L. Castledine and Julia Sandy-Bailey, “‘Stop That Rambo Shit . . . This is Feminist Softball’: Reconsidering Women’s Organizing in the Reagan Era and Beyond,” in Breaking the Wave: Women, Their Organizations, and Feminism, 1945–1985, ed. Kathleen A. Laughlin and Jacqueline L. Castledine (New York: Routledge, 2011), 191–208. Gabriner, “Come Out Slugging!,” 53; Daneel Buring, Lesbian and Gay Memphis: Building Communities Behind the Magnolia Curtain, Garland Studies in American Popular History and Culture (New York: Garland, 1997), 156; Stephanie Gilmore and Elizabeth Kaminski, “A Part and Apart: Lesbian and Straight Feminist Activists Negotiate Identity in a Second-Wave Organization,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 16, no. 1 (January 2007): 109, 110.

- Enke, Finding the Movement, 148; Vicki Gabriner quoted in Sears, Rebels, Rubyfruit, and Rhinestones, 178; Elizabeth Knowlton quoted in Sears, Rebels, Rubyfruit, and Rhinestones, 178.

- The ALFA Newsletter published a special conference issue to inform those unable to attend of panel discussions and ways to connect to local southern women’s organizing. GSELC Committee, ALFA Newsletter Special Conference Issue, July 1975, 1.

- Gabriner, “Come Out Slugging!,” 56.

- Minnie Bruce Pratt, interview by Kelly Anderson, March 16–17, 2005, Jersey City, New Jersey, Voices of Feminism Oral History Project, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, MA.

- GSELC Committee, ALFA Newsletter, 4; La Shonda Mims, “Drastic Dykes: The New South and Lesbian Life,” Journal of Women’s History 31, no. 4 (Winter 2019): 123; Harper, discussion; Yolanda Retter, “On the Side of Angels: Lesbian Activism in Los Angeles, 1970–1990” (PhD diss., University of New Mexico, 1999), 198.