“In a community driven archive, it’s not an individual or institution deciding what goes into the archive, but rather a collective of people who are able to curate and present their own history.” —Bryan Giemza

Many of the photographs you see in the pages of Southern Cultures are drawn from the library collections of UNC-Chapel Hill. As we look back at our past 22 years, we would like to highlight one of our primary sources that is often buried in our endnotes.

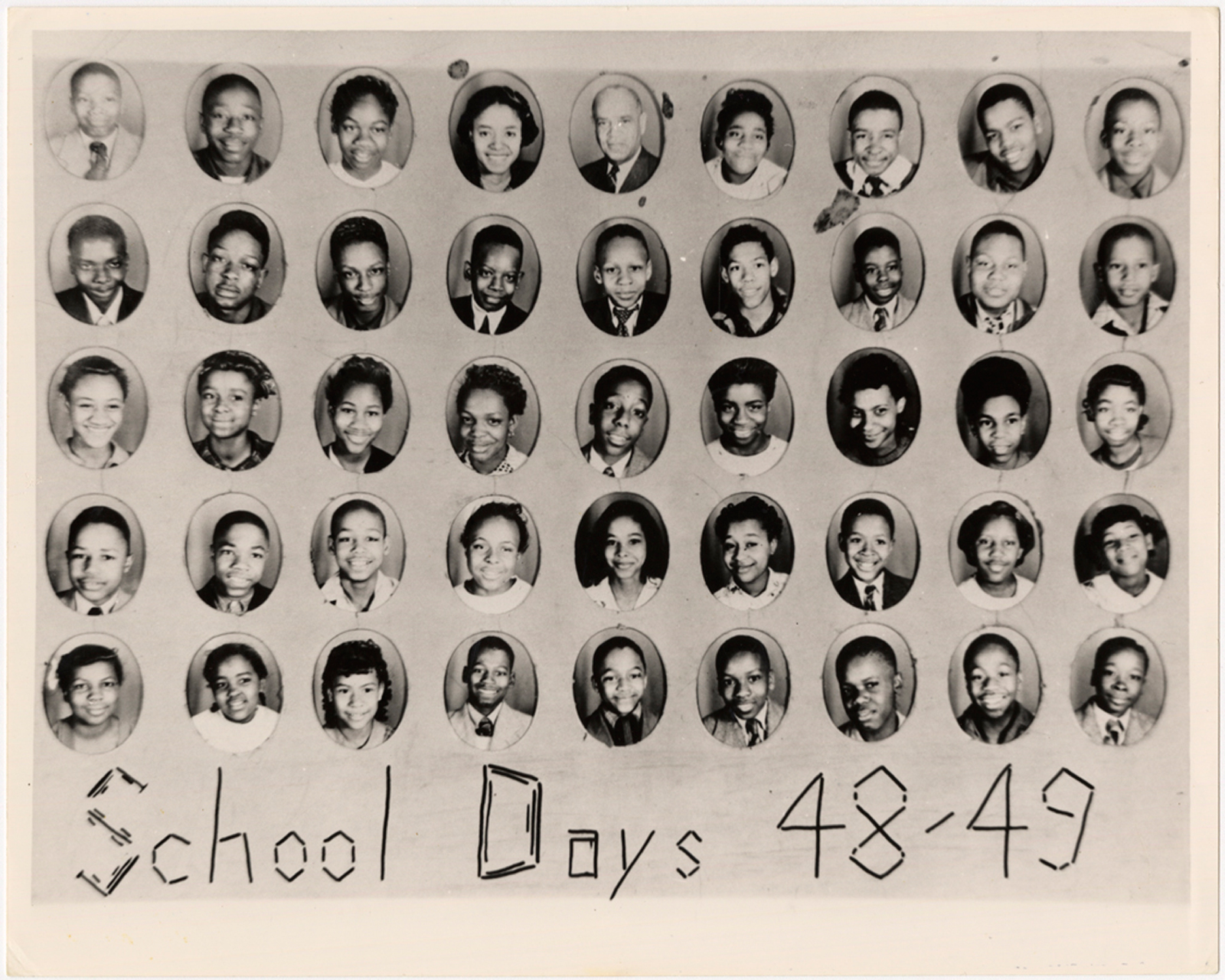

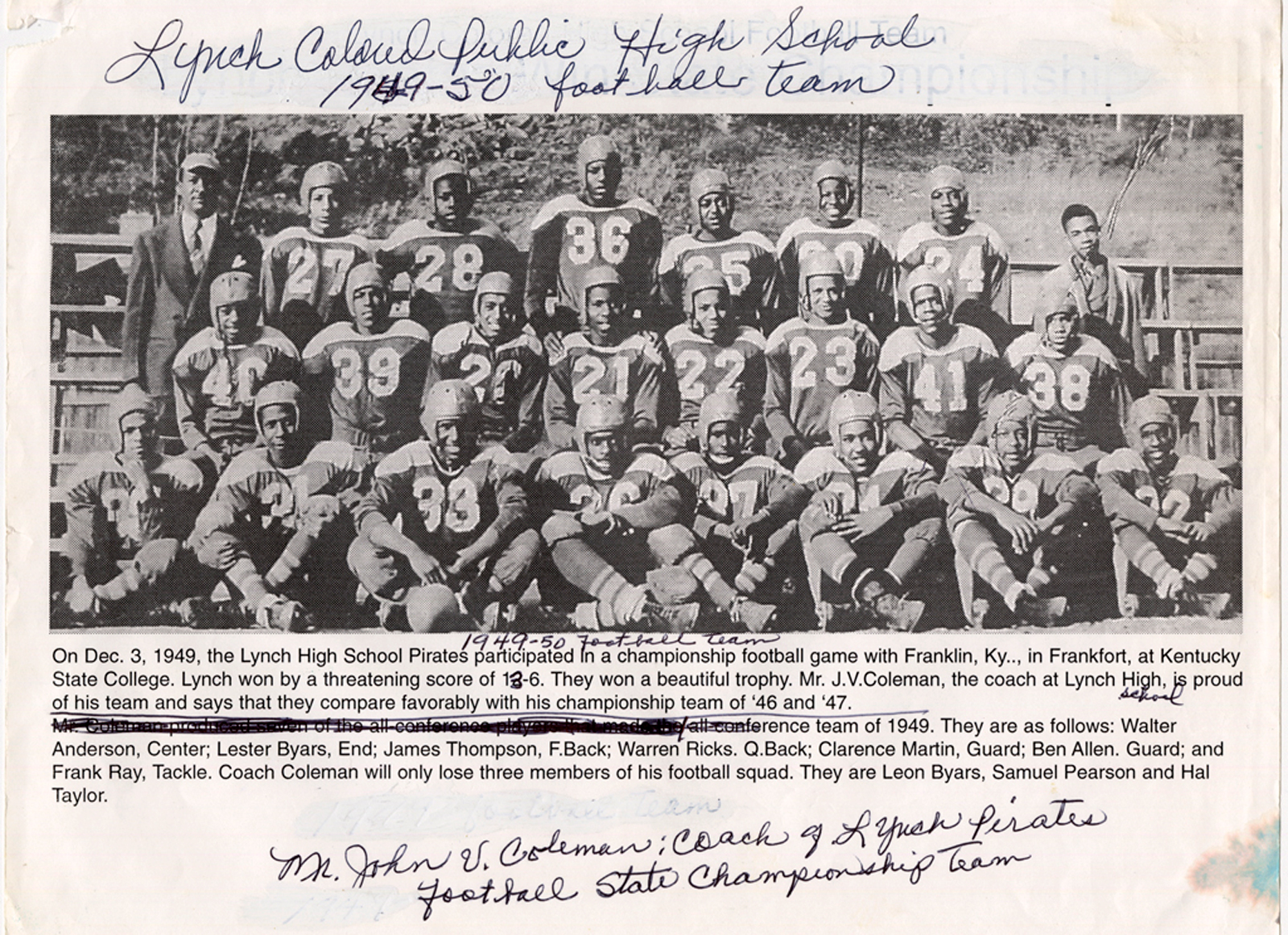

The Southern Historical Collection (SHC) encompasses more than twenty million items, including everything from photos to diaries, letters, scrapbooks, and maps. Their archives are rich in Civil War correspondence, plantation ledgers, and literary arts, and they are expanding their repository of civil rights, Jewish, and contemporary materials. In addition, the SHC has committed to growing its community-driven archive program. Southern Cultures is proud to have published some of this work in our Documentary Arts issue this spring with an essay by Karida Brown, who was instrumental in establishing the Eastern Kentucky African American Migration Project (EKAAMP) collection at UNC. In her words, “One of the purposes of EKAAMP is to provide a space for these invisible subjects to inscribe themselves in the institutional archives so they will not be written out of history.”

“As a university of the people, our efforts really distinguish us in this area of genuine and authentic service,” explains SHC Director Bryan Giemza in the Spring 2016 issue of the library’s Windows magazine. “Communities that are in control of their own history are more likely to be invested in preserving it and sharing materials that would otherwise remain hidden.”

Brown was instrumental in establishing the Eastern Kentucky African American Migration Project (EKAAMP) collection at UNC. In her words, “One of the purposes of EKAAMP is to provide a space for these invisible subjects to inscribe themselves in the institutional archives so they will not be written out of history.”

This initiative was one of the first participatory archives at the SHC. The collection lives online and continues to be participatory—visitors to the site can name individuals in photos. In 2015, Brown helped organize the community-driven exhibit Gone Home at UNC Chapel Hill.

In her Southern Cultures essay, “On the Participatory Archive: The Formation of the Eastern Kentucky African American Migration Project” in our Spring 2016 Documentary Arts issue, Brown shares how this archive was formed in response to the sincere desire of the people she met during her fieldwork in Kentucky. As she interviewed people in their homes, men and women shared photos, yearbooks, and clippings with her. “It became clear to me that they shared a collective sense of urgency to preserve their history,” says Brown. “In their archive—their memories, their nicknames, their performances and rituals—remains a unique and rich history that lies virtually untold.”

In partnership with the Southern Historical Collection, we share a glimpse into the EKAAMP collection.

“I was sitting in Mr. William Schaffer’s apartment conducting my survey. He was eighty-six years old at the time and had lived alone for the last fifty years. His home was meticulous, yet filled with a lifetime of memories. During the interview, I asked him about his high school education. He got up and lumbered to his bedroom and brought back a copy of his high school diploma and all of his report cards from the Lynch Colored Public School. I asked him if he had ever served in the military. He reached over to his drawer and pulled out a picture of himself serving in Germany during World War II. Once I finished, he said, “You know, once I die, all of this stuff will end up in a dumpster. I don’t have any children or living siblings. I hope you will come back and take some of this so you can get the story right.”

—Karida Brown, January 2013, Chicago, Illinois

“I showed up to Mr. John Steward’s home at three in the afternoon to conduct the survey. I was hoping to be no more than ninety minutes because I had a social event to attend back in Los Angeles that evening. When I walked in, he had five boxes neatly presented in the foyer. We spent the next three hours going through documents relating to his stepfather (a coal miner in Benham, Kentucky), the formation of the Los Angeles chapter of the Eastern Kentucky Social Club, and his military, educational, and professional experiences. As time dwindled, we raced through the survey and I got myself together to leave. He looked at me with a bit of confusion and said, “You’re going to take the stuff, right?”

—Karida Brown, March 2013, Aliso Viejo, California

For more information on the EKAAMP archive, visit ekaamp.web.unc.edu and read Karida Brown’s Spring 2016 Southern Cultures essay.