“If the Cyclorama becomes an artifact for students and historians and ceases to be a monument in which Atlantans invest memory and meaning, it will be . . . one example of how we might retire a monument to the Confederacy, without erasing the history that the monument carries.”

On May 1, 1886, Jefferson Davis visited Atlanta for the last time. He had agreed to speak at the unveiling of a statue of the late Georgia senator Benjamin Harvey Hill. The former president of the Confederacy looked gaunt and frail. He sat on stage during the ceremony, and one might imagine that the crowd of fifty thousand watched his every fidget. “We hope on that day to hear the real, old fashion rebel yell, having never heard it,” wrote the DeKalb Chronicle‘s editors. “We reckon it will offend no one, but if so, let it offend.” And sure enough, when Davis rose, the crowd roared, Yee-Haw! or, perhaps, Yay-Hoo! Davis gave a short speech praising the late senator, and then the crowd dispersed.

The man who introduced Davis that day was Henry Grady. Grady was Davis’s opposite. The chief apostle of the New South movement, Grady was a master of reconciliation. To the North, he preached understanding through commerce; to the South, glory through growth. And though Davis drew the crowd, Grady was master of ceremonies. Davis was seventy-eight, Grady thirty-five. Perhaps this was a final farewell—a moment of transition, Old South to New. But the New South lost Grady too soon. Who could have known that both men would die three years later? Henry Grady outlived Jefferson Davis by seventeen days.

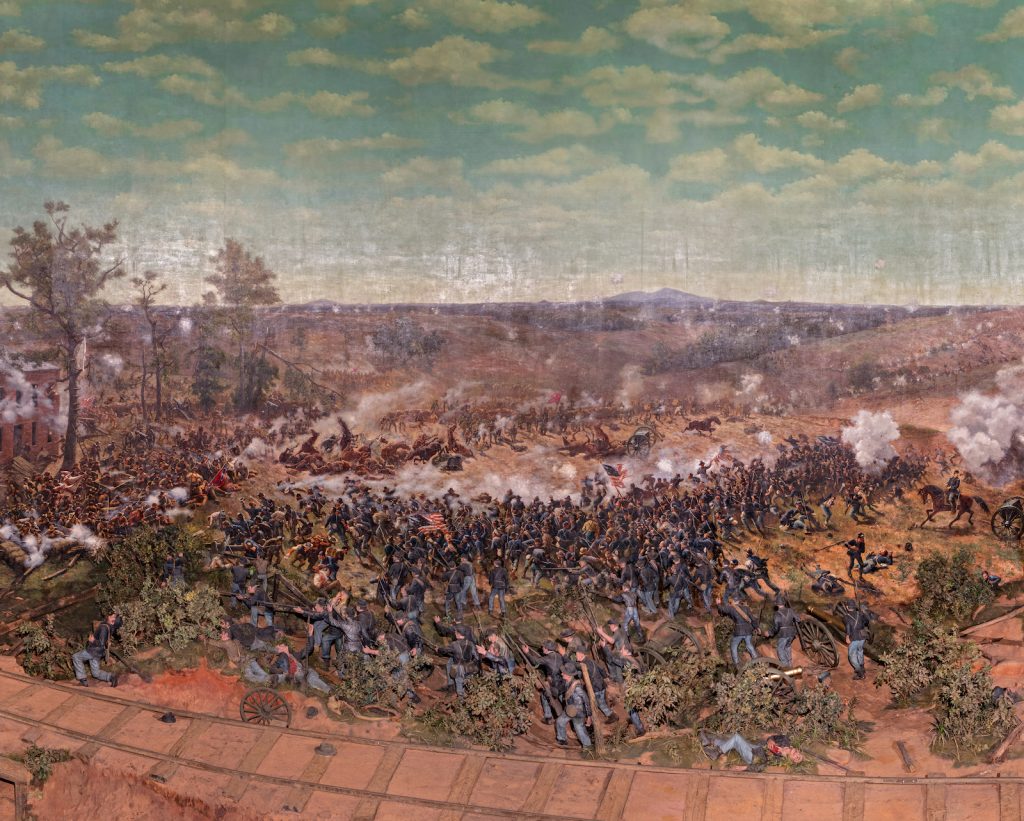

While Davis spoke in Atlanta, thirteen German painters in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, were putting final touches on the Cyclorama of the Battle of Atlanta. One month later, on June 29, 1886, the Cyclorama would premiere in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Cycloramas are enormous circular panorama paintings designed for exhibition in large rotundas. The viewer stands in the center, completely surrounded. The canvas of the Atlanta Cyclorama was 49 feet high, 382 feet long, and weighed over 9,000 pounds. It depicts a single moment in the Battle of Atlanta: 4:45 PM on July 22, 1864. From 1886 to 1892, it would travel the nation: Minneapolis, Detroit, Indianapolis, Chattanooga, Baltimore, and then Atlanta, where it remains today.2

The canvas of the Atlanta Cyclorama was 49 feet high, 382 feet long, and weighed over 9,000 pounds.

In 1892, Atlanta was caught in an ideological tug of war. If you believed Henry Grady, the city was a thriving business hub, the North’s gateway to the South and, equally, the South’s to the North. It was progressive, forward-thinking, willing to put its past behind and focus on a prosperous future. But if you believed Davis—and the crowd of admirers who cheered him on—Atlanta was far from finished with the Old South. Indeed, Atlantans had just begun reckoning with their city’s role in the Civil War. Like the rest of the region, they cushioned bitter memories with nostalgia, a longing for a past that never was and a present that never would be.

The Cyclorama shares Atlanta’s ambivalence. Its meaning has proved malleable. It is possible to see a Union rout or a Confederate victory, a narrative of glorious emancipation or of tragic Lost Cause, an appeal for reconciliation or an acknowledgement of division. The Cyclorama reflects either an Atlanta that longed for its past or an Atlanta where even monuments were ahead of their time.

The form is unstable, too: the Cyclorama is neither art nor monument nor commercial enterprise—and yet, it has been all three. The painting resists definition.

For that reason, the Cyclorama was, and still is, the perfect Atlanta monument. In the 1890s, a wave of commemoration and nostalgia made the Cyclorama a symbol of a Confederate victory that had never happened, a beacon for the Lost Cause, and a reminder of how Atlanta had almost changed the course of the War and saved the Old South. In the 1930s, Atlanta’s boosters and business leaders tried to use the Cyclorama to meld this Lost Cause ideology with a new “Atlanta Spirit” driven by commercial progressivism. What they got was less a melding, more a tacit agreement to disagree: Old and New South began to coexist. It took decades of gradual progress to rupture the dual nature, old and new, of 1930s Atlanta. And when that rupture occurred in the 1970s, the Cyclorama was once again swept into a debate about memory. This time, suburban whites clung to an Old South and clashed with Atlantans who wanted to re-appropriate the Cyclorama for an Atlanta remade by the Civil Rights Movement, no longer mired in myths of Confederate glory.

The Cyclorama shares Atlanta’s ambivalence.

The Cyclorama depicts a battle; fitting, then, that it became a battleground—a longstanding site of contested memory. Examining its history helps us to see how Atlanta’s memory of the Civil War has evolved and changed. But it tells us even more about how Atlanta chose to imagine itself—and it shows that, as late as the 1970s, perhaps even today, it has not yet figured out just how southern it wants to be.

II.

Georgia businessman Paul Atkinson brought the Cyclorama to Atlanta in 1892. It was a wise move. Tourists and Atlantans of all classes crammed into the temporary wooden rotunda that housed the painting. Confederate veterans who had fought in the battle gave glowing reviews. Never had they seen a more realistic depiction of war. And even better than its realism, they said, the Cyclorama was on the South’s side! The Atlanta Constitution wrote: “The painting is wonderful, from the mere fact that it is the only one in existence where the Confederates get the best of things.”3

Except they hadn’t. The Confederacy lost the Battle of Atlanta, and that loss marked a turning point in the Civil War. In July 1864, a growing number of northerners were fed up with President Abraham Lincoln. The frustration was mutual; Lincoln complained in private that northern civilians expected a victory without a fight. With the November 8 presidential election fast approaching and Peace Democrats breathing down his neck, the president felt trapped. He could sway the electorate, perhaps, with sustained Union gains over the summer, a few major victories to put the end in sight. The election—and, by extension, the fate of the Union—rested on the outcome of the Atlanta Campaign.4

Atlanta was one of the South’s few remaining industrial hubs. The The Battle of Atlanta lasted one full, bloody day. In the Cyclorama, But Hood did not muster his forces in time. Union reinforcements, led * * * In the 1880s, a surge of nostalgia coursed through the nation. In 1884, Milwaukee’s William Wehner had just become manager of the

city was founded in 1837 as a tiny town called Terminus, so named

because it marked the zero-mile point of the newly constructed Western

& Atlantic Railroad. The railroad brought people, business, and a

name change, and by 1860 Atlanta was a rapidly expanding urban center

with a population just under 10,000. Then came the war. Soldiers in gray

turned Atlanta into a stronghold. In 1864, General William Tecumseh

Sherman’s Union Army marched its way South from Chattanooga, through

North Georgia, and into the outskirts of the town known as “Gate City of

the South.”5

though, time freezes at 4:45 PM. Four Confederate brigades, led by

General Arthur Manigault, have just broken through the Union line near

the Troup Hurt House, where the Union’s 15th Corps is stationed. Right

next to the house lies Captain Francis Degress’s Battery. Manigault’s

Confederates storm the Hurt House and overpower Degress’s men, who shoot

their own horses to prevent the enemy from hauling away their

artillery. There is now a sizable gap, from the 15th to 17th

corps, in the Union line. Confederate General John B. Hood gathers

troops to launch an assault; a Union soldier wrote in his diary: “The

day at this time looks gloomy for us.”6In the Cyclorama, time freezes at 4:45 PM.

by General John A. Logan, poured onto the scene and beat back the

Confederates, resealing the line and ending the assault. By nightfall,

the Union had firmed up its line and Sherman had readied his troops for a

months-long siege. Atlanta fell in September. Sherman torched the city

and marched to the sea. Lincoln won reelection in November. The war

ended a year later.7

Veterans, quiet for a decade or so after the war, now wanted to share

their stories, and civilians wanted to hear them. Century Magazine

published its famous “Battles and Leaders of the Civil War” series from

1887 to 1889. Veterans’ reunions became “a major commercial event” in

many American cities. There was a material and intellectual market for

reconciliation. “The prevailing theme was the equality of soldiers’

sacrifice on both sides,” notes historian David Blight. Far easier to

remember bravely fought battles than to dissect the reasons bullets were

fired.8

American Panorama Company. Taking advantage of the demand for

reconciliationist remembrances, Wehner hired a team of German cyclorama

painters a year later and set his sights on Atlanta. The painters

travelled south and constructed a 40-foot tower at the intersection of

Moreland Avenue and the Georgia Railroad. By using their tower, battle

maps, and official records, the Germans were able to piece together an

image of the battleground. Together, the artists interviewed dozens of

Confederate veterans—with an interpreter, since not one of them spoke

English.9

We know very little about who commissioned Wehner to paint the Atlanta Cyclorama and even less about why Wehner and his team chose 4:45 PM. But given the high demand for reconciliation narratives of the war, it seems possible, even likely, that the decision to paint such an ambiguous juncture in the battle was a commercial one. Cycloramas needed to sell, and here Wehner had found a Civil War moment that appealed to the North and South alike. The North would see Logan riding in to crush the Confederates. The South would see Manigault’s vastly outnumbered men ferociously taking on a Union army and, for an instant, beating them.

Cycloramas needed to sell, and here Wehner had found a Civil War moment that appealed to the North and South alike.

Regardless of the intentions behind it, the Cyclorama went beyond reconciliation; it managed to glorify a northern and southern victory at the same time, depending on the audience. Outside the South, it premiered to huge crowds in Minneapolis, Indianapolis, and Detroit as “Logan’s Great Battle.” In Indianapolis, there was “naught but praise and wonderment at the realism” of the painting, wrote the Sentinel. When the crowd spotted Logan and his fellow Union generals, they cheered and stomped their feet.10

In Chattanooga, the Cyclorama—after some minor adjustments—was met with similar praise from a very different audience. Paul Atkinson had just purchased the painting from Wehner and wanted to tour it in the South. There was just one troublesome image that caught Atkinson’s eye: a small cadre of Union soldiers escorting a group of clearly petrified Confederate prisoners. Atkinson’s solution was simple enough; when the Cyclorama opened in Chattanooga, the Confederate prisoners were no more. In their place, a small group of terrified Union soldiers appeared to be fleeing the battle. It is easy to see then how the Constitution, upon the Cyclorama’s arrival in Atlanta, could earnestly proclaim that the Confederates “get the best of things.”11

By 1892, the narrative of reconciliation was competing with a second narrative that was rapidly gaining popularity in the South: the Lost Cause. Three organizations in particular—the United Confederate Veterans (UCV, founded 1889), the Confederate Veteran Magazine (1893), and the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC, 1894)—set out to correct history. The war, they explained, had been an unjust attack on the Old South, whose culture deserved veneration and whose warriors had fought bravely to defend their way of life. They held Confederate reunions, hung Confederate flags in white public schools, and built monuments to honor Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and other Great Confederate Men. In Richmond, Virginia, they erected a huge statue of Lee in 1890 that “marked the entry of the Lost Cause into the national mainstream.”12

Atlanta, with its uneasy blend of reconciliation and Lost Cause narratives, never got a Monument Avenue like Richmond. The city’s two major events in the 1890s were clear examples of its paradoxical mix of New and Old South. In 1895, Piedmont Park hosted the Cotton States and International Exposition. The Cotton Expo emphasized business and the future: “It was a scene that marked an era in the South’s history. It marked the industrial awakening of a great section and signalized a new departure in the relations of the races,” wrote the Constitution.13

Three years later, however, Atlanta hosted its first Confederate Reunion. On July 22, the 34th anniversary of the Battle of Atlanta, Confederate veterans marched through the city streets. It poured rain, but the soldiers kept marching in view of large crowds—just under fifty thousand, the Constitution bragged. Spontaneous renditions of “Dixie” rang out. Tourists and Atlantans lined Capitol Avenue, packed tight, craning for a glimpse. Businesses closed down for the day. These men were “living monuments,” wrote the Constitution. Boosterism could wait.14

* * *

By the time Confederate veterans streamed into the city in 1898, the Cyclorama was under city ownership and resided in Grant Park, just south of downtown. The painting was still viewed by some as a reconciliationist image that also reflected Atlanta’s boosterism. “Nothing but the closest scrutiny would enable you to observe the real from the imaginary,” raved a Confederate veteran from South Carolina. A ticket to view it cost 10 cents—cheap, but enough to scare off “all undesirable people,” according to the Constitution. Newspapers proudly published the annual revenue of the Cyclorama as if to say, Even our monument makes money. And it was truly Atlanta’s only monument. The city had no traditional site of Civil War memory. Its best-known statue was of Henry Grady (erected in 1891). Fittingly, Atlanta only remembered the Civil War with an art form made for business.15

Despite these hints of reconciliation and New South ideology, however, the vast majority of commentary on the Cyclorama in the 1890s and early 1900s reveals an Atlanta where the Lost Cause reigned. Nearly everything written about the Cyclorama, including city-approved park pamphlets, spouted Lost Cause tropes. The Constitution reminded readers that the Cyclorama recalled a battlefield “once drenched with heroic southern blood.” Newspapers, official pamphlets, and veterans all claimed the painting portrayed a Confederate victory. When the Confederate veterans rolled through Atlanta in July 1898, the city decided not to charge them for admission. Business—and the city of Atlanta—knelt at the feet of the Confederacy.16

This commitment to the Old South, driven by bitterness and longing, became gruesomely clear on September 22, 1906. Newspapers reported that four black men had sexually assaulted four white women (the reports were false). That night, thousands of white Atlantans formed a mob. They searched, stalked, and slaughtered every black man, woman, and child they could find. They tortured one man to death, and cut off his toes and fingers as souvenirs. They lugged the bodies of their victims to Marietta Street, in front of City Hall, where they stopped at a large bronze statue on a marble pedestal. They piled the bodies at the feet of Henry Grady and his New South.17

III.

In 1937, Atlanta elected a new mayor, William B. Hartsfield. Hartsfield monopolized city politics for almost three decades, serving as mayor from 1937 to 1941 and again from 1942 to 1962. Though undeniably racist, he was also a proud Atlantan who wanted his city to look good in the eyes of the North and South alike. It was not an easy balance to strike. Blacks flowed into Atlanta in the late 1930s, and whites responded by locking down their neighborhoods or by abandoning ship and leaving the city for the suburbs. Hartsfield tried to keep the peace at all costs, even if that meant a slow but steady march to desegregation. Though blacks didn’t have a vote in state primaries and many were disenfranchised by a Georgia poll tax, Hartsfield suspected those Jim Crow laws would fall and made a point of placating all of his constituents: blacks, white supremacists, and a business elite who shared his goal of a thriving, nationally prominent metropolis.18

Where did a Cyclorama that had been appropriated into a Lost Cause narrative fit into Hartsfield’s new Atlanta? The painting had moved up the block in 1922, to a new, $10,000 stone building right next to the Grant Park Zoo. The majestic home was inaugurated with a day of distinctly Lost Cause celebrations run by the udc, Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV), veterans themselves, and the Atlanta Park Board. After the initial attention and celebration, however, lack of press and low attendance indicate that interest in the Cyclorama faded, and the painting passed through the 1920s relatively unnoticed.19

Fortunes changed in 1934, when the city received a grant from the Works Progress Administration’s (WPA) Federal Art Project to restore the Cyclorama, now in disrepair after more than a decade of neglect. The project went to Wilbur G. Kurtz, an Atlanta painter and amateur art historian. Kurtz and his team revamped the entire viewing experience, installing the diorama and a spotlight that directed audience members to different sections of the painting in sync with a recorded lecture (written by Kurtz) that played to a quiet rendition of “Dixie.” (Their effort was inspired in part by the success of motion pictures, which had created a higher standard for realism.) New lighting would create the illusion of movement; the idea, said technician Burt Wellborn, was “[t]o put life into it. It’s a shame to leave it as cold and dead as it is.” Cold and dead—a far cry from the “fearful reality” of the 1890s.20

In 1937, as Kurtz’s crew worked away in Grant Park, Mayor Hartsfield tried to unmoor the Cyclorama from the Lost Cause. “It must be remembered,” he cautioned, “that this picture is not a shrine or memorial. It was painted purely for exhibition purposes, not to be worshipped or venerated as a relic, but as a vivid portrayal of the Battle of Atlanta.” This was a strikingly bold and explicit attempt by the mayor to reorient the Cyclorama toward his “New South” Atlanta, one focused on realism and reconciliation. The mayor sought to preempt organizations—the UDC chief among them—who would deify the painting. But when Hartsfield and Kurtz resurrected the Cyclorama, they accidentally resurrected the Lost Cause as well, with a little help from Margaret Mitchell.21

The restored painting opened on January 11, 1939, well in time to welcome Rhett Butler and Scarlett O’Hara to town. Gone With the Wind would premiere at the end of the year, on December 15, and in the days before the city had quietly rewound some seventy years. The Loew’s Grand Theater had been specially renovated, its façade transformed into a southern mansion, and newspapers ran thick souvenir editions with detailed instructions for the Rebel yell. A few hours before the premiere, Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh visited the Cyclorama. “It is the most wonderful thing I have ever seen,” Leigh raved.22

The Cyclorama was back in the news, and the Lost Cause was back in Atlanta (if, that is, it had ever left). The religious language Hartsfield had cautioned against was everywhere—newspapers declared the Cyclorama building a “mecca” and a “Shrine to the Confederacy.” The press feasted on over-the-top reactions that suited the Old South narrative: two viewers faint each week, claimed one reporter; a thirty-five-year-old woman spotted Sherman in the painting and stormed out; and in August of 1939—seventy-five years after the Battle of Atlanta—a withered Confederate veteran accidentally bumped into a plaster model of a Union soldier in front of the painting, sized him up, and whacked him with his cane.23

The Cyclorama was back in the news, and the Lost Cause was back in Atlanta (if, that is, it had ever left).

Hartsfield pivoted deftly. Rather than resist the surge of Lost Cause frenzy inspired by Gone With the Wind and the Cyclorama’s restoration, he pushed painting and film together. He took the stage at the premiere of Gone With the Wind in December 1939—choosing, like Grady in 1886, to play emcee, even as the thousands of boys draped in Confederate gray did not stand for the Atlanta he wanted. He publicly requested that costumes from Gone With the Wind and any war “relics” in Atlantans’ homes be donated to the Cyclorama museum. He pronounced a citywide celebration of the 76th anniversary of the Battle of Atlanta in 1940, “a memory day.” And he met privately with Kurtz to commission a short book on the Cyclorama and its history.24

Though Hartsfield was careful to avoid expressing his frustrations publicly, it is difficult to imagine that the painting’s stubborn link to the Lost Cause pleased the man who wanted to make sure that “no business, no industry, no educational or social organization [was] ashamed of the dateline ‘Atlanta’.” But Gone With the Wind was popular everywhere, including in the North, and Hartsfield must have realized that linking the Cyclorama to the movie might help integrate it into Atlanta’s image without much fuss (and that the link might also boost the painting’s commercial prospects). During his Cyclorama tour, Gable joked that it would be nice to see his character in the painting. Hartsfield took him seriously. A few months later, Atlantans noticed an extra plaster figure in the diorama: a dying Rhett Butler, mustached and true-to-life.25

The Cyclorama’s resurgent popularity continued through the 1940s. The painting drew around 110,000 visitors in 1940 and over 120,000 in 1941, and the steady rise continued until 1949, when an all-time record of 168,000 people paid the 50-cent fee for admission. Kurtz’s short book came out in 1954. The press lauded it as a necessary work, and the city advertised it as “A book for collectors, students, teachers, members of the UDC . . . whoever you are!” It seemed that Hartsfield and Lost Cause promoters had reached a compromise: the Cyclorama could remain a symbol of the Lost Cause so long as it did not interfere with Hartsfield’s plans for a nationally lauded Atlanta. But perhaps this gives too much credit to the mayor, who may have had little influence over how the Cyclorama was remembered. Hartsfield had tried, at least rhetorically, to shift the meaning of the painting—but Atlantans, tourists, and the UDC had soundly rebuffed him.26

And yet, even as the Cyclorama made its way back into the public eye, riding the coattails of Hollywood celebrity and Lost Cause revanchism, Atlanta was advancing rapidly toward the Civil Rights Movement. In 1946, when the Supreme Court declared Georgia’s poll tax and all-white primaries unconstitutional, Harts-field saw an opportunity: Atlanta could lead the South into an era of gradual integration. He desegregated the police force in 1948, and did the same with public schools in 1961. Even this snail’s-pace integration met resistance. Nevertheless, Atlanta was ahead of the South and was on its way to national acclaim as a forward-thinking metropolis. Hartsfield had ambitious plans—a major league sports team, a civic center, a downtown that gleamed with skyscrapers—and those plans required that Atlanta accept Civil Rights advances, avoid recourse to Lost Cause history, and steer well clear of racist violence.27

For the first time since 1892, the Atlanta Cyclorama and its city were completely at odds. The Cyclorama had remained a reminder of “old” Confederate glory, while Atlanta had become a city led by politicians aspiring to an upstanding image of “new” progressive boosterism. “We want these Yankees to see what a good fight the Confederates put up,” said a Cyclorama tour guide, referring to Navy sailors who visited Atlanta on their way back from serving in World War II. Atlanta’s political elite wanted those Yankees to see just the opposite: booming business and an international, cosmopolitan, integrated metropolis. Hartsfield left office in 1961, having struggled to reconcile his city’s opposing identities.28

IV.

Wealthy white families had been trickling out of downtown since the invention of the car, but in the 1960s, as African Americans moved into Atlanta’s political structure and the city enacted federal civil rights regulations on busing and school integration, they left in droves. Whites who could afford to make a new home in a suburban enclave just north of the city did so, and by the end of the 1960s, Atlanta faced what historian Kevin Kruse has called a “politics of suburban secession.”29

As whites left for the suburbs, they tried to take the Cyclorama with them, fearing that blacks would overrun their “Shrine to the Confederacy” and arguing that the painting would fare better alongside the newly completed confederate memorial at Stone Mountain. But whites who had remained inside the city limits, and inside Grant Park in particular, built neighborhood coalitions to keep the Cyclorama in Atlanta. When it served their purpose, they went so far as to adopt a full-blown emancipationist narrative of the painting. Atlanta’s first black mayor, Maynard Jackson, made a concerted effort to make that emancipationist narrative stick.

* * *

Atlanta is defined by its neighborhoods. This was especially true in the 1960s, when city officials, activists, and real estate agents all realized that neighborhoods were the perfect unit for local action. Grant Park was no exception. The neighborhood took its name from Lemuel P. Grant, a wealthy Atlantan who designed the city’s fortifications during the Civil War. Grant donated 100 acres of land—designated as park space—to Atlanta in 1882. Within a decade, the park housed two of the city’s main attractions: a zoo and the Cyclorama. The area remained white and middle-to upper-class, with roomy Victorian houses, until the early 1950s. But by the 1960s, construction of a six-lane interstate through the neighborhood’s northern blocks left it limping, and slum conditions in Summerhill and Peoplestown—two majority-black neighborhoods that bordered Grant Park to the west—threatened to leak across neighborhood lines. Grant Park whites felt as though their comfortable downtown region was under attack.30

The tipping point came in 1962, when the Grant Park School board redesignated one of its schools as black to compensate for over-enrollment. Real estate agents immediately declared the neighborhood “zoned for Negroes.” Whites fought back—”attEntIon, BlocK BustErs . . . your treacherous tactics have turned our neighborhood into a battleground,” read one advertisement from the Home Protection Committee. But white fear eventually trumped white anger, and wealthier families fled to suburbs up north. Despite white flight and the stoking of racial fears, though, Grant Park did not “turn black.” Many of the neighborhood’s white homeowners were older and retired, without the means or will to haul themselves out to suburbia. Instead, the neighborhood morphed into an integrated anomaly. By 1972, Grant Park was 63.3 percent white, 36.1 percent black. Unlike almost every other neighborhood in Atlanta (and certainly every other neighborhood south of downtown), it had become more, not less, racially diverse.31

Because of that racial diversity, Grant Park entered the 1970s politically and spatially divided. Blocks were strictly segregated—whites lived on the west side of the park, blacks on the east—and whites worked to prevent blacks from accessing public spaces. Though the neighborhood remained majority-white, then-mayor Ivan Allen Jr. lumped it in with the rest of southside Atlanta and ignored its needs, letting it sink into poverty and discord. Whites found it far easier to dismiss Grant Park as “lost” than to admit that it had undergone complicated and messy integration.32

* * *

Just as some in the white community abandoned Grant Park and other nearby neighborhoods, they were also content to leave the Cyclorama behind. Mayor Allen didn’t prioritize the painting as Hartsfield had; the new Atlanta was focused on Civil Rights and growing at a record pace, and the Cyclorama seemed anachronistic. It was also—once more—in a distressed state. The painting had been coated with buttermilk in the 1930s to dull the shiny original coating (linseed oil), and now the whole canvas was encrusted with what one reporter delicately called “a thin layer of cheese.” It was not until engineers reported in 1968 that the painting might collapse that people again began to pay attention. As in the 1930s, the idea of the Cyclorama teetering on the brink of permanent destruction seemed to mobilize Atlantans.33

Just as some in the white community abandoned Grant Park and other nearby neighborhoods, they were also content to leave the Cyclorama behind.

This time, the mobilization came from the suburbs, where residents wanted the Cyclorama for themselves. In 1958, the Georgia legislature had picked up a failed 1916 UDC proposal for a huge relief of Davis, Lee, and Stonewall Jackson at Stone Mountain, just outside Atlanta city limits. Residents wrote to their newspapers urging the city to donate the Cyclorama to sit at the mountain’s base. Moving the Cyclorama to suburbia would be, as one resident put it, the “finishing touch”—not just for Stone Mountain but for white flight. Georgia Secretary of State Ben Fortson supported the proposal, calling Stone Mountain the “Civil War capital of the world.”34

But Atlanta politicians and business leaders did not want to relinquish the Cyclorama to Stone Mountain. Doing so would imply that Atlanta was willing to cede its past to segregationists. In his 1970 inaugural address, newly elected mayor Sam Massell called the question of where the Cyclorama would rest “one of the matters of utmost importance to the city,” sending a message to the Georgia legislature that Atlanta would not yield to Stone Mountain without a fight. Instead, Massell wanted to move the Cyclorama to a popular intersection in downtown Atlanta called Peachtree Triangle, where it would demonstrate quite plainly why Cyclorama was of “utmost importance” to the city: “it will make some money.” This provoked a small group of white Grant Park residents to form Cyclorama Restoration, Inc. (CRI), in the hope of raising funding and support to restore the Cyclorama right where it was.35

The CRI‘s pitch was, in part, a defense of the Grant Park neighborhood. Senator Jack Stephens, a board member of the CRI, told city aldermen at a hearing in 1973 that “the Cyclorama is really an asset to our community. Let the people on the south side, from the middle income to the low income, enjoy one of the historical sites of their city.” The Cyclorama was now tangled up in neighborhood and class politics. It didn’t just matter that the painting stay in Atlanta; it mattered that it stay in Grant Park.36

In 1974, Maynard Jackson beat Massell and became Atlanta’s first black mayor. His election sparked a surprising shift in Cyclorama rhetoric: people began describing the painting as a monument to northern victory. Paul Bolster, a white Grant Park resident and the secretary of the CRI, made a particularly astonishing statement in 1975: “The Cyclorama could be used as a good teaching tool, showing the reconstruction of the South, the moving away from slavery. It would be important for the black community. Maybe in the past too much emphasis has been put on the white man’s part.”37

It is possible, of course, that some members of the CRI, Bolster among them, sincerely believed that the Cyclorama could provide a more nuanced view of a complex—and, to date, lopsided—history. But the Cyclorama had never been of any interest to black Atlantans. Residents of Summerhill or Peoplestown were unlikely to pay to see a painting billed as a symbol of southern glory and often staffed by guides who were members of the UDC. And among the CRI‘s members were representatives of the SCV and UDC, many of whom lived in or around the wealthy, white Buckhead neighborhood in north Atlanta. It seems unlikely that the primary motivation behind the CRI was black education in Grant Park.38

One possible explanation for the swift shift in rhetoric was that the CRI knew that its cause lacked sufficient popular support. By 1976, the CRI sported just 264 members and was receiving only a thin trickle of donations. In a 1977 meeting a member said she felt that “many people believe that only the Grant Park area people are interested [in keeping the painting in the neighborhood].” Spurred on by Jackson’s election, the CRI may have realized that the Cyclorama needed to appeal to a black audience for there to be hope of its staying in Atlanta.39

Jackson himself made it very clear that he wanted the Cyclorama to remain where it was. He officially proclaimed July 22, 1975 (the 111th anniversary of the Battle of Atlanta) “Cyclorama Day” (in an unmistakable revision of Hartsfield’s “memory day”). And he ranked the Cyclorama restoration second on a list of projects that needed funds from a 1976 federal grant. By 1979, though, it looked as though Atlanta wouldn’t come close to the $7.6 million required for a complete restoration. A Constitution poll showed resounding support for the Cyclorama—4,797 readers wanted it restored, only 25 didn’t—but many respondents blamed Jackson for the decay, accusing him (and, by extension, Atlanta) of throwing away the South’s history. Seeing an opportunity, Stone Mountain City Councilman Rusty Paul effectively dared the Jackson administration to divorce the Cyclorama from its Lost Cause roots: “It seems as though . . . Atlanta officials are somewhat embarrassed by the presence of the Cyclorama,” he taunted.40

And then, out of nowhere, an anonymous donor gave $2 million toward the restoration of the Cyclorama in Grant Park. Jackson pieced together the other $5.6 million, and the painting closed for restoration until 1982. On December 14, 1981—on the eve of the 42nd anniversary of the Gone With the Wind premiere—the mayor held a press conference after viewing the newly restored Cyclorama. There, he articulated a new narrative: “Here we had this magnificent cultural asset that was rotting where it was. It had to be saved. Some people say it is ironic that this administration would work to save the Cyclorama. I see no irony. Suffice it to say: Look at who won the battle.”41

* * *

When the restored Cyclorama opened in 1982, Jackson appeared to have won his battle, too. Newspapers admitted, for the first time, that the painting had northern origins and depicted a Union victory. The Cyclorama still provoked emotional responses, but of a different sort; as one Atlantan put it, “I never saw a more stirring anti-war argument.” For the most part, Atlantans and some southerners seemed willing, if not eager, to see the Cyclorama as monument to the horrors of the War or even to Emancipation.42

But Kruse’s point about white flight still stands. The city of Atlanta may have refashioned the Cyclorama’s significance, but the Lost Cause had not disappeared; it had simply moved away. White segregationists didn’t need the Cyclorama; they had Stone Mountain. Even so, it’s tempting to read the 1970s debates about the Cyclorama as an indication that, at least within Atlanta, a proper reckoning with the past was finally possible. The diverse motivations that drove CRI members to support the Cyclorama make clear that Atlantans were increasingly willing to accept a painting and a city with splintered, messy identities. Jackson’s powerful press conference and the fact that the Cyclorama remained in Grant Park could even be seen as signs of the city shirking its lingering connection to the Lost Cause and, perhaps, embracing some form of a “New” New South.

Panel 6 of 6.

Beneath the new rhetoric, though, lay unaddressed issues of race and class. The troubled integration of Grant Park during the 1960s and 1970s—and the complete lack of integration in other downtown neighborhoods—is evidence that a corrected past did not necessarily make for a harmonious present. Atlanta no longer had to fight blatant segregationists and Lost Cause believers. Instead, the city’s image was plagued by subtler problems of local discrimination—problems evident in the very neighborhood that housed the painting. Ironically, the recasting of the Cyclorama made those problems easier to ignore. As the Cyclorama restoration crew scraped away at layers of buttermilk film, they revealed a sharper, clearer vision of the past. But that vision could also obscure the present.

V.

Today, the ornate, columned stone building in Grant Park is but an empty shell. In 2018, the Atlanta Cyclorama will have a new home in Buckhead at the Atlanta History Center. Except for the bestial purr of 12-cylinder automobiles, the neighborhood is silent, cocooned in its wealth. Lawns are pristine. “Big green breasts,” Tom Wolfe once called them.43

To be clear: the Cyclorama is not moving to Buckhead because suburban whites have snatched it up, or because it has once again become a symbol of Lost Cause glory. The reason is financial. Over the last few decades, the Cyclorama had once again slipped quietly into the background. Mayor Kasim Reed created the Cyclorama Task Force in 2011 after declaring it economically unsustainable. The History Center acquired the painting, thanks in part to Lloyd and Mary Ann Whitaker, who gave a $10 million gift toward its restoration. Mr. Whitaker emphasized that neither he nor his wife wanted to resurrect a symbol of the Lost Cause. Indeed, his view of the Cyclorama actually strikes a definitively “New South” tone. “The ‘Battle of Atlanta’ was the death knell of the Confederacy,” he told one reporter, adding, “We are going to be able to preserve that in the literal sense with the painting, and symbolically with how that led to the Civil Rights movement.”44

History Center president Sheffield Hale echoes the sentiment, saying that the Cyclorama will transition from attraction to artifact. Hopefully, Hale maintains, visitors will be able to view the Cyclorama in its proper context. The “Cyclorama Fact Sheet” on the History Center’s website claims that the painting “Tells a story that extends well beyond the Civil War . . . [It tells] the story of how the Civil War has been remembered, used, misused, forgotten, and interpreted over time.”45

The History Center is trying to retire the Cyclorama and place it in the past. The idea is that the Cyclorama’s days of provoking new Civil War memory and reflecting Atlanta’s desired image are over. No more emotional breakdowns by audience members. No more Confederate veterans with canes who attack plaster Union soldiers. No more Gone With the Winds. But also no more mayors who need to reorient the Cyclorama to reflect their idea of Atlanta. No future battles over where the Cyclorama should be placed—at Stone Mountain or elsewhere. The History Center is making an assumption that directly opposes that of Atlanta in the 1930s and 1970s: that restoring the Cyclorama and attracting a new wave of crowds will not revive the painting. Rather, it will ensure that the Cyclorama remains truly, permanently dead.46

Restoring the Cyclorama and attracting a new wave of crowds will not revive the painting. Rather, it will ensure that the Cyclorama remains truly, permanently dead.

This latest—perhaps last—stage in the life of the Cyclorama is well timed: it occurs at a moment of widespread debate over the role of Confederate monuments in today’s South. On June 17, 2015, Dylann Roof reminded America that the Lost Cause was still alive. Roof walked into the Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, and killed nine people because they were black. As he drove away, a bronze statue of John C. Calhoun, the pro-slavery and pro-secessionist politician, looked on from atop a giant pillar half a block away from the church.47

The dark symbolism of Calhoun’s statue did not go unnoticed. In the wake of the Charleston Massacre, nearly every southern city has begun to question whether outsized statues and memorials to Confederate and Old South icons really ought to stand proud and public. There is no consensus. Some argue that to remove the monuments would be to erase history, others believe it is time the South stop venerating its ugly past. Many have suggested that cities like Charleston move their monuments away from public squares and into places where they can call upon the past without glorifying it, perhaps in a museum.

* * *

Amidst this debate, the Cyclorama’s move to the History Center—to a museum—is historic. If the Cyclorama becomes an artifact for students and historians and ceases to be a monument in which Atlantans invest memory and meaning, it can stand as an example of how a city might retire a monument to the Confederacy without erasing the history that the monument carries.

But the painting has never just held memories of the Civil War; it holds memories and images of Atlanta as well. It reflects a city in flux, full of rhetoric, always aware that its desired future and remembered past are in conflict. Atlanta remained caught between images of itself as progressive and as southern (and as progressively southern), determined to confront the past but reticent to confront its scars. We might ask, then, what the Cyclorama’s move from Grant Park to Buckhead, from a public space to a private one, from attraction to artifact says about today’s Atlanta. So long as Atlantans continue to reimagine their city and struggle with its contradictions, the Cyclorama will live on: Atlanta’s evolving monument.

This essay first appeared in the Summer 2017 issue (vol. 23, no. 2).

Daniel Judt is a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, where he studies politics.