The most shocking moment in Harlan County, U.S.A. (1976) looks at first like an abstract painting. An organic shape, small and shiny and pinkish white, sits on a dark, rough ground. Even after an enormous disembodied finger pokes into the frame, the visual alone remains indecipherable. Previous scenes have shown striking miner Lawrence Jones lying in a coma in the hospital, the sounds of the breathing machine keeping him alive and the clicks and beeps of hospital monitors clearly audible. The quick cut to the scene of the glistening glob leaves the viewer visually bewildered. What makes the scene so difficult to watch and hear is not the visual image, however, but the words. The soundtrack gives the image meaning. “That’s the brains of a goddamned fellow who tried to do something,” a male voice says. The camera then pans up from the finger to an arm, a man’s naked shoulder and chest, and then a face as the voice speaks again, coming out of the lips that at last appear: “Piss ants carrying off a man’s brains while they are in the hospital dying.” It is the sound—this first disembodied and then located voice—that tells viewers what they have seen in this scene.1

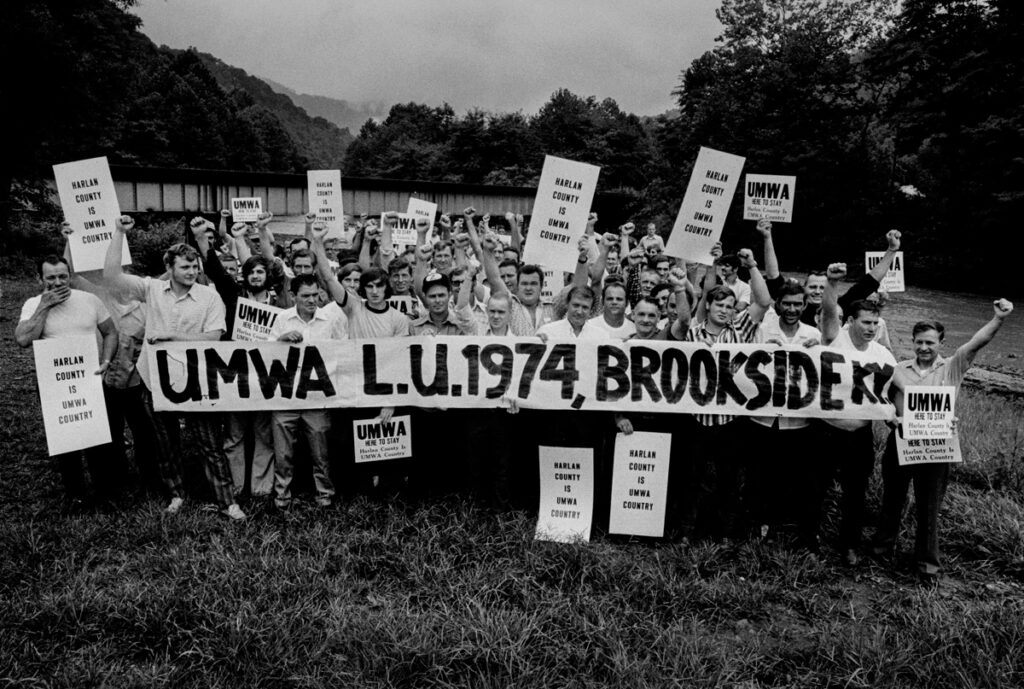

In her 1976 Academy Award–winning documentary Harlan County, U.S.A., Barbara Kopple labors to wring a sense of visceral realism out of the overexposed visual landscape of Appalachian poverty. Images of the raw materials of life in eastern Kentucky help convey the struggles of Brookside miners and their families during the 1973–1974 strike against mine owner Duke Power for the right to work under a United Mine Workers contract. In the film, bits of brain blasted into a dirt road, mucus coughed up by miners with black lung, chunks of coal hacked out of the earth, and cigarette smoke drifting from the noses of miners and their wives on the picket line struggle to counter romanticized images of poor Appalachians. Kopple cannot directly engage all of the senses, but she certainly tries, visually evoking touch (the finger and the piece of brain) and smell (the bodies of people who do not have indoor plumbing) and taste (the endless white bread and baloney sandwiches of the picket line). Harlan County, U.S.A. does some of its most compelling work, however, by engaging the sense of hearing. In Harlan, sound anchors, explains, and makes “authentic” visual imagery compromised by the long history of documentary making in Appalachia.

As Michel Chion, Rick Altman, Claudia Gorbman, and other scholars of film sound have argued, film works visually as well as aurally, even in the misnamed era of “silent” film. Film sound affects what the viewer simultaneously sees, even as film images affect what the viewer simultaneously hears. Sound interprets visual images, provides continuity and context, hides edits, eases scene changes, creates mood, and makes montage possible. It also plays an essential role in creating what the film scholar Bill Nichols calls the “voice of documentary”: how a film imagines and addresses its audience. Voice here functions materially and metaphorically, as both recorded voices and ambient and other sound contribute to the “voice” of the film.2

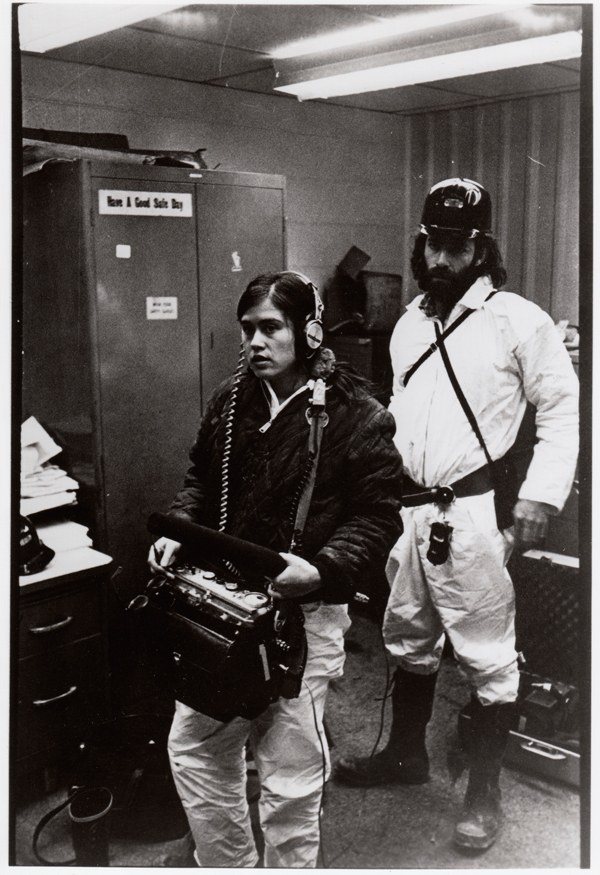

Barbara Kopple not only directed and produced Harlan County, U.S.A., but she also served as the film’s sound person, carrying the microphone on a boom and the Nagra recording equipment on her body. The invention and distribution of this relatively cheap and portable sync sound equipment in the early 1960s enabled even independent, poorly-funded documentary filmmakers to begin recording sound on location. Harlan County, U.S.A. is filled with sounds recorded this way—the voices of local people speaking, shouting, and singing; the hard breathing of protestors running in fear and the rasping breaths of people with black lung; the noise of people laughing, crying, and screaming; and the sound of instruments like fiddles, banjoes, and guitars, calling birds, chirping crickets, and barking dogs; the noise of the vehicles that carry workers into the mine and the grinding machines that dig the coal and the conveyor belts that carry the coal out; the sound of car engines, the crack of pistol fire, and the rat tat tat of machine guns; and the echoing thunder of a mine exploding. These sounds slide into each other without pause. They form layers. Often emerging at first without visual referents, they conjure missing spaces and alternate times. They produce emotions. They disrupt familiar visual images. Accented with sounds recorded in other ways—a few songs, speeches, and press conferences—they form a rich and complicated sound-scape. In Harlan, Kopple’s complex use of sound offers a powerful solution to the particular problem of representing the Appalachian poor in the 1970s and to the challenges independent filmmakers experimenting with direct cinema techniques faced in countering the authority of classic television documentaries.3

Sound anchors, explains, and makes “authentic” visual imagery compromised by the long history of documentary making in Appalachia.

In 1973, Barbara Kopple traveled to Appalachia to make her first film, a documentary about the union reform movement Miners for Democracy (MFD). Twenty-seven years old, she had apprenticed with the direct cinema pioneers Albert and David Maysles and participated in the Winter Soldier film collective documenting Vietnam veterans’ testimonies about their participation in wartime atrocities. In eastern Kentucky to investigate how rank and file miners took over the United Mine Workers Union (umw), she and her small crew became enmeshed instead in the already underway 1973–1974 strike at the Brookside Mine in Harlan County. There, former MFD activists, then working for the UMW national office, plotted strategy with local miners in the first test of the more militant, MFD-backed union leadership led by Arnold Miller. Kopple ended up spending about a year living in the coal camp with the family of a striking miner.4

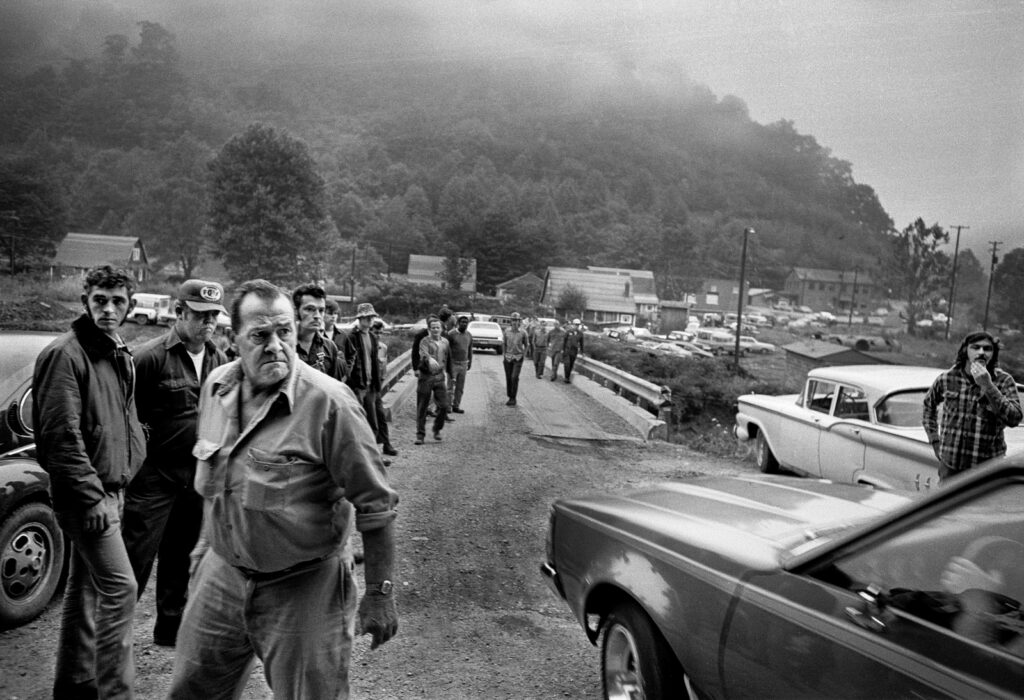

In Harlan, Brookside strikers and their families, threatened by armed strikebreakers, began to see the film crew’s presence on the picket line as a form of security. In a scene in the film, a striker being arrested yells, “Take pictures, Barbara!” as the police drag him past the camera. In another scene, a miner describes the effect of the filmmaker’s ongoing presence on the picket line: “They ain’t going to commit murder in Technicolor.” When a strikebreaker shot a miner away from the line, Kopple took her camera to the site to film the evidence. Young strategists working for the United Mine Workers national office, in turn, generated the publicity—taking miners to picket Wall Street, where the stock exchange sold Duke Power stock, and placing feature stories in national magazines—that enabled Kopple to stay in Harlan after she received death threats. Late in the conflict, Kopple even screened some of her raw footage to raise money for striking miners’ families. The process of making the film played a critical role in the victory at Brookside, and the completed film spread word of the miners’ democracy movement far beyond the coalfields. Like other documentary audio, photography, and filmmaking in this period, Harlan County participated in the social movement it also depicted—in this case, the union reform movement and, particularly, the political alliances young middle-class activists were trying to forge with U.S. workers. The process of making a film about political activism was itself a form of political activism.5

Harlan County draws some of its power from the inherent drama of the Brook-side Mine strike. But Kopple’s film also gains strength from its relationship to a long tradition of outsiders documenting a romanticized and “backward” Appalachia that began in the last third of the nineteenth century and to the mid-twentieth century reimagining of this fantasy in the folk music revival and the documentary-making it inspired. The miners, the union activists, and Kopple all knew pieces of this history and self-consciously used it to appeal to audiences beyond the mountains. In particular, Kopple’s film employs visual images and musical styles long documented and circulated as markers of Appalachian difference. By subtly building a rich soundscape of music as well as other noises, and setting it in tension with the documentary’s cinematography, Kopple both evoked and challenged familiar images of Appalachian poverty. In Harlan County, sound works to make the images “real” again, to make them available for alternate meanings.

Kopple produced Harlan County, U.S.A. in a visual and aural landscape already crowded with sights and sounds of Appalachia. As Henry Shapiro argued in his 1978 book Appalachia in Our Mind, Americans from outside the region invented the idea of Appalachia as an exotic and separate place that could be exploited both materially and culturally. The earliest surviving photographs of Appalachia taken in the mid-nineteenth century present the region as an island of otherness created by nature. After the Civil War, some Americans began to interpret this Appalachian difference as a cultural and natural treasure in need of preservation. Scholars determined to salvage a supposedly vanishing culture and activists determined to save a supposedly primitive people converged on the region, collecting artifacts from quilts and pie safes to baskets and pottery, creating folk festivals to display dancing and music, and building settlement houses, mountain schools, and medical clinics. This work accelerated in the early twentieth century and continued through the Depression era. For most Americans from outside the region, Appalachia increasingly meant a place of poor people and rich culture.6

Sound, in the form of music, played an essential role in generating this idea of Appalachia as a reservoir of primitive and authentic culture. “Song catchers,” as locals called outsiders like English ballad collector Cecil Sharp, rode into mountain hollows on horseback asking families to play and sing their oldest songs. They wrote down lyrics and sometimes also transcribed the music and made notes about performance styles. Reformers opened schools to teach children and adults basic academic subjects and to preserve local forms of expression and crafts that they saw as valuable. In eastern Kentucky, for example, Katherine Pettit and May Stone opened Hindman Settlement School in 1902 and held classes in traditional balladsinging, along with reading and writing, through the 1920s. These institutions often entertained visitors with students’ performances of what reformers understood as authentic mountain music. Later, annual folk festivals like the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival in Asheville, North Carolina, founded in 1928, and the White Top Folk Festival in Grayson County, Virginia, founded in 1931, gathered together Appalachian musicians and dancers for an audience of both locals and outsiders. In the late 1930s, John and Alan Lomax began traveling in the region with a several hundred pound “portable” acetate disc recorder, and their fieldwork produced some of the oldest surviving location sound recordings. After World War II and the invention of lighter and easier to use recording technology, scholars and musicians retraced by car the routes earlier song catchers had traveled, convincing locals to sing for their machines.7

Visual documentation of the region accelerated in the Depression era and peaked again in the 1960s as photography and film images exposed the material deprivation of many rural mountain people’s lives in ways that also often highlighted their indigenous cultural resources. Photographer Doris Ulmann traveled in the area in 1933 and 1943, making pictures of craftspeople and their products. A selection of these images appeared in the 1937 book Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands. wpa photographer Ben Shahn shot striking miners in Scott’s Run, Virginia, in 1935. Photographers working for the Tennessee Valley Authority (tva), including Lewis Hine, took pictures of life along the river in the mid-1930s. Roy Stryker, head of the fsa’s photography unit, sent wpa photographer Marion PostWolcott to eastern Kentucky in 1940 with instructions to capture “the remote back country area: going to school; burying their dead; delivering mail; bringing groceries up the creek bed, barefoot, or on horseback; how people spent their leisure, their recreation and games.” Some of the earliest documentary films of Appalachia date from this period as well. After serving in the Frontier Nursing Service, Mary Marvin Breckinridge Patterson made the 1930 film The Forgotten Frontier about the nurses who traveled on horseback to treat mountain people in their isolated cabins. Shots of people living without modern resources justified the service of the heroic nurses. Tennessee’s Highlander Folk School, an influential rural version of the then common urban labor schools, collaborated with the politically radical Frontier Films to produce the 1937 film People of the Cumberland. Combining footage shot on location with reenacted scenes of the murder of a miner, this film presents mountain people’s exploitation by industry and their fight to overcome their poverty through education and unionization. Scenes of locals performing and listening to music suggest the strength and authenticity of the people’s culture despite their economic oppression.8

As a completed documentary film, Harlan County, U.S.A. circulated most directly amidst an outpouring of documentary work, including photography, audio recordings, and films, made in and about the rural U.S. South from the 1950s through the 1970s. These documentary films about the South fall into roughly two categories: films made by the three major broadcast networks, National Educational Television and, after 1970, PBS, religious organizations, and local public television stations, usually using strong voice-over narration and demanding some sort of reform, on the one hand, and more self-consciously artistic films made by independent filmmakers influenced by the direct cinema movement on the other. Television cameras recorded presidential candidate John F. Kennedy’s campaign visit to Appalachia in 1960 and President Lyndon Johnson’s declaration of a War on Poverty from the front porch of a cabin in Inez, Kentucky, in 1964. Throughout the Sixties, video and film crews became as common in the hollows as song catchers had been in an earlier era. Each new documentary—NET’s Appalachia: Rich Land, Poor People (1969) was an important example—seemed to compete with previous films in depicting poverty and deprivation. The artist and scholar Martha Rosler has argued that these liberal documentaries imagined an audience of viewers with the political agency to try to fix the problems identified in the films. The people represented in the films, on the other hand, appeared mostly as victims, without the agency to help themselves. By the time Kopple began shooting in Harlan County, most people who watched television news programming had seen these kinds of Appalachian images.9

Independent filmmakers like John Cohen, Pete Seeger, Les Blank, and Bill Ferris made documentaries in the rural South inspired as much by their love for what people at the time called “folk” music and other forms of cultural expression as by any radical commitment to social change. Many of them were also musicians involved in the folk music revival in the late 1950s and 1960s. Cohen, a filmmaker, photographer, and musician, first traveled to eastern Kentucky in 1959 to find inspiration for an album of songs about the Great Depression that his revivalist string band the New Lost City Ramblers was recording in New York City. In Appalachia, he believed, he could experience both the poverty and the people’s culture that characterized the Depression era. In 1961, he went back to eastern Kentucky armed with a silent movie camera, as well as the sound recording equipment he took on his first trip (he edited his film footage and separate sound recordings together). His lyrical film about musicians and mountain life, The High Lonesome Sound, helped create a new southern folk film genre.10

By the 1970s, a desire to document U.S. working-class and rural life more broadly inspired many independent filmmakers who paid for their films with grants from the NEA, NEH, private foundations, and regional and state level arts commissions and humanities councils. Over two hundred documentary folk films were made during this period. In conjunction with the folk music revival and its later offshoots, the blues revival and the bluegrass revival, these films represented southern rural life as outside of modern time, a preserve of authenticity worth celebrating, and a readily available tool for indicting contemporary America’s “fake” culture and flawed democracy.11

Within the region, the Appalachian Film Workshop, founded by Bill Richardson in 1969 in Whitesburg, Kentucky, and later reorganized as a collective and renamed Appalshop, began with a mission to teach documentary filmmaking techniques to local youth. Armed with cameras and sound recording equipment, Appalachian people could then make their own documentary films to counter the negative representations made by outsiders. In 1971, Appalshop began releasing documentaries that explored the mountain economy, rural schools, and local politics and culture using on-camera interviews, voice-over narration, and direct cinema techniques. Director Gene DuBey’s 1973 Appalshop documentary Strip-mining in Appalachia, for example, employed interviews with local residents and environmental experts as well as voice over narration to document the devastating environmental and human costs of the then relatively new and little understood practice of open pit mining, later called mountain top removal. Kopple used footage from director Ben Zickafoose’s 1971 Appalshop film UMWA 1970: A House Divided about the Miners for Democracy insurgency within the United Mine Workers in Harlan County. Zickafoose had also been interviewing Brookside residents for a film about the coal camp in the year before the strike broke out there. Kopple and her crew saw some of his materials although the film Zickafoose eventually made, Coal Camp: Life Below the Tipple, was never released. Director Mimi Pickering’s 1975 Appalshop film Buffalo Creek Flood documented a community damaged by and fighting against a mining company a year before Kopple finished Harlan County, U.S.A. Other early Appalshop films focus on local musicians, artisans, traditional healers, and craftspeople. Nimrod Workman, a miner and singer who appears in Harlan County, was the subject of a 1975 Appalshop film directed by Scott Faulkner and Anthony Sloan, Nimrod Workman: To Fit My Own Category.12

Kopple’s Harlan County draws on the documentaries of the Appalshop collective, not just in her use of their footage and choice of subjects but also in her linkage of sound and image. Appalshop films use direct cinema techniques but also often violate them with the inclusion of historical film footage, non-diegetic sound (sound whose source does not exist within the film), and interviews, the kind of pragmatic mix of methods Kopple employs in Harlan County. And Appalshop films, to varying degrees, all try to solve the problem faced by Kopple: how can documentary films make outsiders see images of the mountain poor and hear mountain music in ways that disturb the meanings and associations conjured by earlier representations of the region as outside of modern America? Ben Zickafoose’s 1971 Appalshop film Coal Miner Frank Jackson provides one illustration of how Appalshop too experimented with using sound to make people see, as well as hear, the region anew. Mining shots had been a staple of Appalachian visual imagery at least since photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston created her coal mine series in the late nineteenth century, and People of the Cumberland portrayed striking miners in 1937. Zickafoose’s mine scene tries to counter those images by conveying the experience of workers entering the mines. The camera sits in the short, squat vehicle used to haul men into mine shafts as low as 4 feet high. The shot focuses on the scene outside the mine, in the daylight, as filmed from the car inside the mouth of the mine so that the opening in the earth provides a frame around the lighted space outside. As the car begins to move into the mine, the lighted scene at the ever more distant mouth of the tunnel becomes smaller and smaller and loses focus. Simultaneously, the only sound, the machine noise of the car moving deeper into the mine, grows louder and develops an echo effect as the visual image becomes increasingly dark and unclear. Zickafoose here uses the slow disclosure technique in reverse as the image and the sound come together to disorientthe audience. The inside of a coal mine, the film suggests, is not a world the viewer knows no matter how many mining images she has seen. Appalshop directors experimented with form, perspective, and subject matter to challenge earlier documentary representations of the region.

Harlan County also came out of and contributed to broader trends in postwar cultural expression. The film’s subject tapped a growing middle-class interest in working-class life and union organizing in the 1970s. And Kopple and members of her small crew, like many independent, politically oriented filmmakers in this period, blurred the boundary between documentarian and activist. Like other postwar documentary makers, they understood their work as both a means of representation and a political act. After their initial visit, they moved in with the families of striking miners for about a year and took part in strike activities as they filmed them. Harlan County became a part of the movement it sought to represent, a film about the strike as well as a part of the strike, an example of participatory documentary. In this way, the film did not simply represent reality but played a role in making a new reality in which the Brookside strikers won UMW recognition.13

Harlan County, U.S.A. begins in the same way Kopple entered events in Harlan County, after the strike at the Brookside mine is already underway. Its structure is roughly chronological, starting one month into the strike, announced on one of the few title cards Kopple uses to explain changes of scene and the passage of time. As the film introduces viewers to strikers and their supporters, their conversations provide information about how the conflict at Brookside began. The central narrative follows the story of the strike and especially the efforts of local miners and their wives and other supporters to picket the mine and keep strikebreakers from working there. To vary multiple scenes of organizing meetings and picketing, Kopple includes three narrative digressions, the story of the Mannington Mine accident, an exploration of the causes and consequences of black lung disease and miners’ organizing efforts to secure healthcare and better health and safety regulations, and the story of the MFD revolt within the MFD. Locals like miner wife Lois Scott and strikebreaker Basil Collins emerge as stars. Women in particular become the dominant characters in the story. In what feels like the end of the film, this central narrative concludes with a Brookside victory as Duke Power accepts the union contract for reasons the film does not make very clear. Then Harlan County proceeds to yet another false ending, exploring UMW leaders’ fight to convince rank and file members to vote for a new national coal contract to replace the contract that expired soon after the Brookside victory. Formally, these false endings suggest the continuation of labor battles and the unending nature of the conflict between miners and mine operators. In fact, beyond the quickly undercut Brookside victory, the film is hard to understand without prior knowledge of UMW history. Overall, Kopple is willing to sacrifice some of the intelligibility that voice-over narration could have provided in favor of Harlan County location footage and the perspective of miners and their supporters. The soundtrack is particularly important here in evoking what it feels like to participate in the strike.14

The soundtrack of Harlan County is particularly important in evoking what it feels like to participate in the strike.

From the very start, the gritty sounds of mine work and miners’ and ex-miners’ voices fill Harlan County‘s soundtrack. As the film opens, the viewer hears a male voice screaming, “Fire in the hole!” three times, giving “fire” two syllables and making “in the hole” into one word. The close-up visual of a miner, recorded in what looks like the light from a head lamp, is sharp-edged, high contrast, and almost unintelligible. The miner manipulates a piece of equipment shrouded in shadow, and the noise of a loud and echoing explosion fills the soundscape. The sound explains the miner’s actions—he has just detonated dynamite. The shot cuts to an image, again seemingly lit with a miner’s headlamp, of darkness and softly glowing smoke down in the tunnel. Quickly, the image shifts again, this time to the opening of the mine, shot from the inside like in Zickafoose’s Frank Jackson. Gently, the same voice, this time disembodied, sings out, “All clear.” Immediately, non-diegetic music begins, and the shot cuts to miners jumping on a conveyor belt built to haul coal out of the mine. The song is “Dark as a Dungeon,” written by Merle Travis, the son of a Kentucky miner, and it describes how the darkness of the coal mine shapes not only the miner’s labor but his soul. The visual followsthe men down the belt into the mine, into the four-foot-high tunnels where they will dig coal. The noise of the mining machines grows louder and mixes with the song until the song ends and the machine sounds take over the soundtrack. The viewer sees the lips of the miners moving in the dim light but does not hear their voices, only the roar of the equipment. The visuals continue full of shadow and light, all contrasts, seemingly shot in location light. On the soundtrack, the machine sounds continue just a little bit too long, covering everything with an audio grit that, like coal dust, works its way inside everything.

Formally, Harlan County‘s soundscape functions as a continuum that holds different visual images, characters, and stories together. The machine sounds start within the music and pour out of it, taking over the aural space before they fade into the sounds of nature. This location noise, in turn, flows without break into the voice of Nimrod Workman singing a song he has written about his time in the mines called “Forty-Two Years.” All the background sounds force the viewer to listen carefully to the lyrics, giving them more sonic power and presence. The viewer hears the voice of the aptly named Workman before she sees the visual of him. While he sings and miners walk home with their lunchboxes after their shifts, the title of the film appears in blood red letters, evoking “Bloody Harlan,” the county’s Depression-era history of labor violence. Workman’s a cappella singing animates a montage of images—footage of the miners’ homes, women hanging laundry and sweeping porches, and kids playing. These shots suggest where the men are headed.

Kopple takes her time getting to the establishing shot. She uses this technique often in the film, a slow visual disclosure in which temporarily non-diegetic sound carries whatever meaning is available. The disembodied sound, especially voices, comes first, and then the source of the sound, especially bodies, comes later. This practice pushes the viewer to become a self-conscious listener too, to pay careful attention to the sound. In particular, the disembodied audio tracks disrupt easy comprehension. They suggest this place and these people are not so open to the eye, not so easily knowable, as other documentary photographs and films of eastern Kentucky have suggested.

When the visual finally cuts to Workman, the old ex-miner is sitting on his porch performing in what the juxtaposition suggests is the very mining village the viewer has just seen. The non-diegetic sound becomes diegetic sound as the singing on the soundtrack syncs up with Workman’s singing body. With the sound and image merging together, Workman sucks a raspy breath and begins a new verse of his song. His singing emphasizes consonants and long vowels. What Roland Barthes calls “the grain of the voice” permeates the soundtrack. These physical qualities evoke a fact the film later reveals, that Workman has black lung and that this disease is the fate of most older miners.15

While the film very subtly cuts to a new visual scene, the soundtrack moves quitesmoothly from Workman’s singing voice to his speaking voice. This lack of a break between song and speech emphasizes the fine line between the two. Interestingly, Workman is much less intelligible when he speaks than when he sings, forcing the viewer to pay even more careful attention to the soundtrack. Background noise—the crackling sound of frozen clothes—again forces the viewer to struggle to make out Workman’s words. Later in the film, non-diegetic fiddle music brings Work-man’s song back repeatedly, as if the old miner and his long history of struggle haunts the story of the Brookside strike. The tune provides a thread of continuity through the complex narrative with its digressions into the history of black lung and the MFD‘s fight to put the rank and file back in control of the UMW.

Other scenes too demonstrate this fluidity of speech and song and suggest a seemingly natural breaking into musicality, as if song is a deeper, more powerful form of expression that reveals something of the interior self. It also evokes the long history, from the song catchers to Lomax, of representing Appalachian people through music. In a later scene in the film, the rising violence on the picket line turns on a moment when the miners’ wives, confronting the armed gun thugs, suddenly begin singing “We Shall Not Be Moved” as they literally hold their ground. Folk romanticism had long shaped outsiders’ sense that black and white rural southerners made music as part of their everyday lives. For direct cinema–influenced filmmakers who avoided non-diegetic music, this seemingly causal music-making was part of what made the region interesting. The evidence suggests, however, that some filmmakers struggled to orchestrate this “life as a musical” effect. John Cohen spent weeks trying to film Roscoe Holcomb singing and playing, and only after he was packing his equipment to leave did the former miner begin to perform. Still, many documentary makers believed Appalachians and other rural and especially poor southerners were natural musicians, and their films, which often feature musicians, confirm this assumption.16

Miller then introduces Florence Reece, an elderly woman well known to the audience as a life-long union supporter. As she begins speaking, the sound of her age-weakened voice evokes the sound of Workman’s voice at the beginning of the film and the whole long history of labor struggles in eastern Kentucky, an association that she makes explicit with her words. Instead of stock footage of armed men clashing with miners, the visual stays with Reece. Her voice—her words, her tone, her Appalachian accent, and her expressions—provide the historical context that is central to the film, the battles over unionization in Harlan County during the Depression: “I am not a miner as you well know, but I am as close as I can be not to be one. My father was a coal miner and he was killed in the mines, and my husband is slowly dying of black lung. My husband and me was in the strike in the thirties in ‘Bloody Harlan County’ and I do mean it was bloody too.” Reece does not only use her voice here. In her words, she calls up the voices of the miners themselves: “And they tell me, these miners say, we are going to stick it out unless Duke Power signs a contract,” and she takes a breath and slows the pace ofher words for emphasis, “or until hell freezes over.” The room erupts in raucous applause and shouts of support. This is not the quilt-making grandma of Appalachian stereotype, entertaining visitors by singing “Barbara Allen,” but a militant labor leader. “The men know,” Reece continues, making sure that they do know, “they have nothing to lose but their chains, and their union to gain.” Forty years later, she still uses the archaic language of the 1930s strike. Then she tells the crowd she wrote this song back then but that it still has meaning today. “I’m old and I can’t sing very well, but you can ask the scabs and the gun thugs what side they’re on because they are workers too.” Through Reece, Kopple puts this question to the members of Harlan County‘s audience.

In this scene, Reece sings two verses and choruses of “Which Side Are You On?” Her voice cracks and warbles, unaccompanied, and her breaths are clearly audible. Her cheeks and lips tremble as she holds the long notes: “If you go to Harlan County / there is no neutrals there / You can either be a union man / or a thug for J. H. Blair.” There is little other noise on the soundtrack. The visual cuts between Reece signing and the crowd intently watching her. A pan of the audience shows some miners from the Harlan Country strike. Some people are clearly singing along, but their voices cannot be heard in the film until the second chorus, when a woman close enough to Kopple for her mic to pick up the sound—it may even be the filmmaker—begins to sing along. Many audience members at the rally know the story of how that Reece wrote the song as armed men working for the mine owners ransacked her home looking for her husband, a striking miner, so they could kill him. Raw, gritty, and militant, Reece’s voice on the chorus becomes the voice of the documentary, repeatedly asking the film’s central question. The “you” of the song suggests the people represented in the film, the locals supporting or opposing the strike. It also ripples outward to embody the film’s audiences as well—people who might own Duke Power Stock, people who might be workers, too, and people who use electricity in the historical moment when the film first circulated, as well as all the people who have watched this film across the years since Kopple completed it.

The sounds in the film, over time, come to support the sides in the strike.

The sounds in the film, over time, come to support the sides in the strike. Male voices speaking with Appalachian accents, voices singing, and women’s voices all embody the striking miner’s side of the fight, while educated male voices speak for Duke Power. (Even Barbara Kopple, born in Bear Mountain, New York, just south of West Point, seems on the film’s soundtrack to have developed a hint of southern accent.) Music always supports the strikers. If Kopple cannot keep fiddle tunes and ballads from signifying primitive authenticity, she can push them to convey labor militancy as well. Machine sounds—of the carts and conveyor belts that take coal out and men into the mines, the machine that grinds the coal at the face of the seam, and the cars that the strikebreakers drive day after day up to and usually past the picket lines—support mine owners. Even the hospital noises—the bleep bleep of the machine that monitors dying miner Lawrence Jones’s breathing—sound sinister.17

Like an exclamation mark, the song “Which Side Are You On?” appears one more time in the film. Sounds of applause continue after Reece’s performance as the visual cuts back to the scenes of the picket line. Soon, Basil Collins, the head “gun thug,” as the strikers and their supporters call him, drives into view. The viewer clearly hears the man ask Kopple, present as the sound person while her camera person films the picket line, “Who you working for, honey?” She answers, “United Press.” He asks for her press card, and she says it is in the car and asks someone to get it for her. They go back and forth, and she asks him, “Can I see your identification, sir?” He says he must have lost it. She replies she must have misplaced hers too, as he smiles and nods and winks at her. On the surface, this scene, all slow southern drawl and politeness, does not seem very hostile. Right before this encounter, however, Lois Scott, a leader of the miners’ wives, tells Kopple how Collins pulled a gun on strikers earlier that day and then wrapped up the weapon and tucked it in his truck. The careful viewer knows what bothCollins and Kopple keep staring at in the vehicle. Soon afterward, a female voice, its source unseen, sings “Which Side Are You On?” against the sound of a fire burning in a barrel and a car engine.

After Reece’s speech, viewers watch the rest of film knowing that the film’s characters are living out the same scenes as their parents and grandparents had before them—the struggle to organize, the poverty of living without even low mine wages, and the hardship and violence of the picket line. In Harlan County, the song, rewritten for the present, continues just like the struggle continues. Those overly familiar visual images—the broken-down shacks, the outhouses, the skinny children—suggest that time does not matter. Murders and mine accidents and victims of black lung just pile up, year after year. Yet the repetition of songs and stories and other sounds in the film also suggests the opposite, that time does matter and all these pasts and these people who cannot quite get a firm purchase on the present are nevertheless not going to disappear and thus must have a future.

Like fiddle music, bluegrass, and ballads, acts of violence in Harlan County both evoke and also cut against the long history of documenting Appalachia. Chapter eighteen, “Fight Fire with Fire,” uses direct cinema techniques to document strikebreakers attacking the picket line. While the visuals confuse and disorient the viewer, the sound pushes the viewer into the fight. At no other moment in the film is Kopple so present; she is the sound person recording events but she is also there, participating in them. Though a few scenes later, a quick visual image of Kopple holding the boom mic and wearing the recording machine over her shoulder appears as the camera pans the crowd; Kopple is easy to miss there. In the attack on the picket line in the early morning and among the nervous picketers the next day, Kopple—through the sound she records—becomes a character in her own film.

The scene opens with barely lit visuals of people standing around and leaning against a car in the pre-dawn dark. The repeated shots of picket duty that precede this moment help the viewer read the very dark, shadowed image lit by the head lights of an approaching car. Sound provides what little clarity exists here, and the noise of people moving, low voices talking, and a car driving by fill out the aural space. A very faint silhouette of a female picketer fills the screen. The visual cuts to a shot as abstract as the piece of the striking miner’s brain as the two headlights become one bright light surrounded by darkness. At this moment, shots and screams ring out. An aura made by the headlights takes over the image, flickers out, and comes back as the effect of a spotlight. More screaming and shooting take over the soundtrack. The visual cuts to a slow motion shot of Basil Collins in his truck, pointing his gun at the camera. A woman’s voice emerges from a roar of background screaming, yelling, “Don’t shoot! Don’t shoot!” The visual moves into normal speed, and Collins lowers his gun and drives out of the shot as women’s screams and shouts continue. Car engine noise gradually replaces the women’s voices.

Just as the viewer begins to think the danger has passed, two young men emerge out of the dark and walk toward the camera. The first one, his jaw bulging with chewing tobacco, keeps coming as Kopple’s head moves quickly across the visual frame. A flesh-colored shape fills the screen—he has attacked Hart Perry, the camera person—and then the image becomes indecipherable. The viewer hears the sound of cracking static and Kopple’s voice yelling, “No!” as the sound suggests she is using the boom mic like a baton. Running sounds and heavy breathing fill the soundtrack as the visual image careens wildly. It comes to rest and focus on a car and some men, and immediately a woman’s voice begins screaming, “Fucking A!” She tells Basil to “take it over there and take your pants off,” and the implication is that he has hidden his gun in his pants. Only then, as the woman’s voice addresses Basil, does the viewer see that Kopple and Perry have run toward the strikebreakers. Collins tells everyone to move along, but Kopple and Perry and the other picketers remain. Someone drives Collins’s truck back across the bridge as he says something unintelligible. The scene ends as Lois Scott’s disembodied voice yells at Collins, “That nigger is a better man than you’ll ever be!” The comment about the lone African American picketer, the former miner and black lung activist Bill Worthington, sings out loudly and crystal clear. Then the soundscape shifts away from location-recorded sound and to an interview in which Scott describesthe attack. Again, the visual lags a few seconds before shifting to sync up with the sound. Kopple has been attacked. She has run in fear. She has fought back. She has felt her heart pound as she gasps for breath. She has become an integral part of the strike.18

A scene filmed the next day on the picket line accents Kopple’s participation. As the camera pans in on a close-up of one of the younger miners, Kopple records her own voice. “Think there’s—” she stumbles and then continues, “they’re going to shoot at us today?” The visual stays on the miner, who replies, “They shot at us yesterday.” Kopple tries again, “What about today?” He replies, “I don’t know,” and then laughs nervously and smiles awkwardly as the visual holds what feels like a beat or two too long. As Kopple asks, “Are you scared?” he simultaneously says, “I hope not.” He takes a breath and answers her last question, “Yeah. Aren’t you?” The scene ends with the repeated sound of his nervous laughter. In this scene, in voice and in direct conversation, Kopple again becomes a character in her own film through sound.

Harlan County, U.S.A. and the outpouring of documentaries about the U.S. South more broadly during the 1960s and 1970s derail the standard account of documentary filmmaking during this period. This history posits and praises a shift away from “naïve” ideas about representing the world out there and toward self-reflexive practices and a documentary “voice” that acknowledges, and indeed focuses on, the place of the filmmaker in the work. The answer, in this kind of thinking, to the problem of representing a diverse and complicated world when most filmmakers are white, educated, middle-class people from suburban or rich urban places, is to support the training and documentary production of working-class people, African Americans, Native Americans, inner city residents, and other underrepresented groups. This is the path taken by Appalshop. Harlan County refuses this thinking. Not simply a film that stands chronologically between direct cinema and subjective filmmaking, it is also a film that refuses this choice. It is about Kopple and how her presence at the events she is filming and recording changes the lives of other people and the course of the strike, but it is also about how those other people are shaping that history and her history, too. It is about the local people of Harlan County, the limits of Kopple and her audience’s ability to know them, and the efforts of both Kopple and those local people to push through those limits. It is about the problematic nature of insider and outsider as cultural and political categories.

Visually, Harlan County gives its audience the old-fashioned pleasures of documentary—the representation of “exotic” people out there, living and working in places and at jobs presented as materially different from the viewers’ own. Aurally, however, the film uses sound to cut against and complicate any sense that visual images are readily knowable and that representation is intelligible without context. Context in the film’s terms in part means Kopple’s own subjectivity and the effects of her presence on the events she is recording—the negotiation of the difference between herself and the others she is representing. But this negotiation is not one-sided. It is not simply self. It ripples outward, like the sound waves produced by a human voice, exceeding the boundaries of the individual. It includes the negotiation of the difference between working-class and middle-class ideas about history and progress, the value of culture and the meaning of authenticity, and the uses of memory. Most profoundly, it questions the aesthetic, political, and cultural meaning of the very categories inside and outside. It asks a question, finally, that it demands an answer to in political terms but which it insists cannot be answered by documentary work in aesthetic terms: “Which side are you on?”

This essay was first published in the Appalachia issue (vol. 23, no. 1: Spring 2017).

Grace Elizabeth Hale is the Commonwealth Professor of American Studies and History at the University of Virginia and the author of Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890–1940 (Vintage, 1999) and The Romance of the Outsider: How Middle Class Whites Fell in Love with Rebellion in Postwar America (Oxford University Press, 2011) and Cool Town: Athens, Georgia and the Promise of Alternative Culture in Reagan’s America (forthcoming in 2017).

1. Barbara Kopple, Harlan County, U.S.A. (Cabin Creek Films, 1976). My work here also draws on my research in the outtake footage, wild tracks, and supporting materials in the Harlan County U.S.A. Collection in the Special Collections Research Center, University of Kentucky Library, Lexington, Kentucky. I thank Barbara Kopple for permission to use this restricted archive.

2. Michel Chion, Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen, translated and edited by Claudia Gorbman (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994); and Chion, The Voice in Cinema (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998); Rick Altman, ed., Sound Theory/Sound Practice (New York: Routlege, 1992) and Altman, ed., “Cinema/Sound Special Issue,” Yale French Studies (1980): 60l; Elisabeth Weis & Belton John, eds., Film Sound: Theory and Practice (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985); Bill Nichols, “The Voice of Documentary,” Film Quarterly 36:3 (Spring 1983): 17–30; and “To See the World Anew: Revisiting the Voice of Documentary,” in Speaking Truths With Film: Evidence, Ethics, Politics in Documentary (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016), 74–89.

3. On documentary work during the 1930s and 1940s, see William Stott, Documentary Expression and Thirties America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973); Richard H. Pells, Radical Visions and American Dreams: Culture and Social Thought in the Depression Years (Harper and Row, 1973); and Jonathan Kahana, Intelligence Work: The Politics of American Documentary (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008). My thinking about documentary culture in the post-1945 US has been shaped by extended conversations with Franny Nudelman, Associate Professor of English, Carlton University.

4. Author’s interviews with Lee Sparks, MFD and UMW organizer, working in Harlan County during the strike, 2010; Fred Harris, “Burning People Up to Make Electricity,” Atlantic Monthly (July 1974), 29–36.

5. I name, define, and trace the history of this category “participatory documentary” in my larger book in progress The History We Make: Participatory Documentary in the US South from the Civil Rights Movement to Black Lives Matter.

6. Henry Shapiro, Appalachia on Our Mind: Southern Mountains and Mountineers in the American Consciousness, 1870–1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1978); David Whisnant, All That is Native and Fine: The Politics of Culture in an American Region (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983); W. K. McNeil, Appalachian Images in Folk and Popular Culture (1989, rpt., Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1995); Allen W. Batteau, The Invention of Appalachia (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1990); Jane S. Becker, Selling Tradition: Appalachia and the Construction of an American Folk, 1930–1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998); Benjamin Filene, Romancing the Folk: Public Memory and American Roots Music (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000); and Elizabeth Engelhardt, The Tangled Roots of Feminism, Environmentalism, and Appalachian Literature (Columbus: Ohio University Press, 2003).

7. Whisnant, All That is Native and Fine; Filene, Romancing the Folk.

8. Allen H. Eaton, Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1937). On FSA photography, see F. Jack Hurley, A Portrait of a Decade: Roy Stryker and the Development of Documentary Photography in the Thirties (New York: Da Capo, 1977); James Curtis, Mind’s Eye, Mind’s Truth: FSA Photography Reconsidered (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991; Nicholas Natanson, The Black Image in the New Deal: The Politics of FSA Photography (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1992); Cara Finnegan, Picturing Poverty: Print Culture and FSA Photography (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2003); and Sara Blair and Eric Rosenberg, Trauma and Documentary Photography of the the FSA (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012). Many of these WPA and TVA photographs are available online on the Library of Congress’s American Memory website at http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/index.html and on Photogrammar, a website that offers search and visualization tools for using the FSA and OWI photography collections, at http://photogrammar.yale.edu/.

9. The Library of Congress’s Motion Picture and Television Reading Room owns good prints of many of these films, including Appalachia: Rich Land, Poor People. Martha Rosler, “In, Around, and Afterthoughts (On Documentary),” in Decoys and Disruptions: Selected Writings, 1975–2001 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004), 152–206.

10. John Cohen, multiple interviews with the author, 2010 and 2012; John Cohen, The High Lonesome Sound (1963); and Tom Davenport and Barry Dornfeld, Remembering the High Lonesome Sound (2003), film available at http://www.folkstreams.net/film,42. On the folk music revival, see Robert Cantwell, When We Were Good: The Folk Revival (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996); and my book A Nation of Outsiders: How the White Middle Class Fell in Love with Rebellion in Postwar America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 84–131.

11. My argument here draws on an archive I have assembled of over 250 southern “folk” films. The best place to start watching these and other interesting films of this type is Tom Davenport’s site Folkstreams at http://www.folkstreams.net/.

12. My arguments here draw upon the Appalshop film archive and my own research on Appalshop, including 2016 interviews with long-time Appalshop director Elizabeth Barrett and Appalshop archivist Caroline Rubens as well as the research of former UVA undergraduate Lauren Tilton, now a visiting Assistant Professor of Digital Humanities at University of Richmond, who wrote an American Studies Honors Thesis on Appalshop and expanded this work in her 2016 Yale American Studies dissertation, “In Local Hands: Participatory Media in the 1960s.”

13. Harlan County U.S.A. Collection; Miners for Democracy Papers.

14. Here and throughout, I draw on my research in the Miners for Democracy papers at the Walter Reuther Library, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI. The strike started on June 30, 1973.

15. Workman in fact lived in Mingo County, West Virginia, not Harlan County, Kentucky.

16. Scott Matthews, “John Cohen in Eastern Kentucky: Documentary Expression and the Image of Roscoe Halcomb During the Folk Revival,” Southern Spaces (August 6, 2008), https://southernspaces.org/2008/john-cohen-eastern-kentucky-documentary-expression-and-image-roscoe-halcomb-during-folk-revival, accessed December 15, 2016.

17. The danger here is that the music will make labor militancy seem as old-fashioned as the songs.

18. There is a great deal to say about Worthington, how race works in this film, and the racial politics of Appalachian poverty in the 1960s and 1970s, but it is the topic of another paper.