And loud they sang, and long they sang, / For they sang to wake the dead. / —Oscar Wilde, “The Ballad of Reading Gaol”

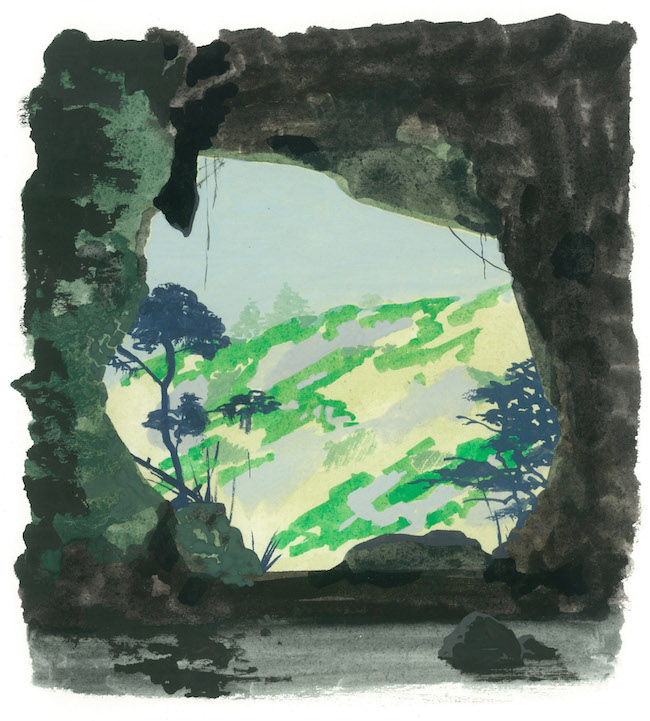

The earliest documented exploration of a deep cave in eastern North America occurred roughly five thousand years ago, in the limestone-rich hills of the Upper Cumberland Plateau along what is now the border between Kentucky and Tennessee. Carrying torches lit with charcoal made from river cane, one or two small groups of hunter-gatherers entered a cave mouth in present-day Fentress County, Tennessee, and ventured thousands of feet into the pitch-black interior, traversing complicated passageways to which later speleologists would give impassable-sounding names like “Only Crawl” and “Towering Inferno.” Charcoal remnants amenable to radiocarbon dating, and, rather more poignantly, some 274 footprints, preserved in the moist clay of the cave floor for thousands of years, have allowed researchers to reconstruct the movements of these ancient cavers—although not, precisely, their motivations for entering the inner recesses of the cave in the first place. In one instance, a set of prints was found along the edge of a pit, where one or more cavers seems to have stood while contemplating the abyss; in another, a lone explorer appears to deviate to examine a striking geological feature in part of the cave’s main passageway, before returning to the group. As one paper published in the Journal of Cave and Karst Studies concluded, the dispersal of the footprints suggests no particular purpose or activity inside the cave, beyond “ambling and searching.”1

It is a felicitous construction. Here, we’ll search out the ways caves have been put to use in southern life and culture and also amble after their more figurative dimensions, as underground or outlaw spaces beyond the pale of good society. Ambling and searching, moreover, brings to mind more than a few country music lyrics, and it is in the realm of country music—particularly the so-called “outlaw country” movement of the 1970s—where the literal and the figurative overlap most evocatively. Country music has always stood in conflicted relationship to a bourgeois culture that has often viewed the music and its practitioners with some considerable reproach; country music has often stood, as it were, with one foot in and one foot out of the cave. The perils and possibilities of that position were rarely clearer than during the outlaw movement of the 1970s. But to make sense of it all, we must start from the bottom.

Country music has often stood, as it were, with one foot in and one foot out of the cave.

When archeologists first came across the Fentress County cave in 1976, they encountered, along with the charcoal traces and the footprints, the skeletal remains of several extinct species of mammals—some of which were as much as thirty-five thousand years old—as well as the bones of at least two adult jaguars. The latter led to the cave becoming known, in places like the Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, as “Jaguar Cave”—although among locals in Fentress County it had long gone by the name “Blowing Cave,” in acknowledgement and appreciation of the cool air that would blow forth from the cave mouth at every time of year. “I’ve seen times when the trees in front of the cave would be white with frost and everything else around there green and normal looking,” remarked Jim Williams, the man on whose property Blowing Cave then lay, when a stringer from the Associated Press questioned him about the prehistoric discovery in his backyard. “People used to come up here just to sit in front of the cave in summer.”2

As it happens, there are as many as seven thousand caves in Tennessee, enough to make it the most cavernous state in the country and to ensure that, as had been the case with Blowing Cave, caves have long served a variety of functions in the daily lives of local inhabitants. Later groups of Woodland Indians mined caves for flint to make stone tools or used them to bury their dead. The earliest European-descended pelt gatherers often lived in caves when they first passed through the Cumberland Gap and into the trans-Appalachian hinterland. With more extensive settlement came more extensive uses for caves: sheltering livestock, storing crops or preserved foods, sometimes even housing schools or churches or, in the case of Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave, makeshift tuberculosis wards.3

I never was made to exist under ground.

During the Civil War, noncombatants at times resorted to hiding out in Tennessee’s ubiquitous caves when enemy troops were on the march. None, however, appear to have endured quite the ordeal as the besieged residents of Vicksburg, Mississippi, who dug caves out of the loess hills rising on the banks of the Mississippi River and lived in them throughout the forty-eight-day bombardment of that city by Union artillery in 1863. “Even the very animals seemed to share the general fear of a sudden and frightful death,” recalled Mary Ann Loughborough, who survived the siege and published an anonymous account of it the following year, under the title My Cave Life in Vicksburg. “I never was made to exist under ground,” she muses, after weeks of doing just that. “I felt, quite like an Indian, I suppose.”4

The wife of a commissioned officer in the Confederate Army, Loughborough’s preciousness was not beside the point. The implication was that livestock and Indians were meant to spend time in caves. Also, runaway slaves and destitute farmers and tubercular cases, and perhaps even the occasional colony of utopian socialists, like those who, in 1896, established a cooperative commonwealth on a 385-acre farm in Dickson County, west of Nashville, the centerpiece of which was a giant cave (sixty-by-ninety feet at the mouth) the colonists named after their idol, the British social critic John Ruskin. But well-bred ladies like Mary Ann Loughborough were not. Caves, in other words, were a part of the daily life of the modern South in the same way that swamplands and mountain hollows were: landmarks on the physical terrain that became imbued with social meaning and, frequently, came to function as markers of social difference as well. In the 1950s and 1960s, when the Ruskin Colony had long since packed its bags and Ruskin Cave had been turned over to more parochial, market-driven concerns, an enterprising local businessman staged a weekly “Saturday Night Hillbilly Hoe-Down” in the cave’s grand entryway. Caves throughout the region were put to a range of recreational uses during the twentieth century, and became engines of a fairly significant local tourist economy—at its peak, Wonder Cave, just outside of Mont-eagle, Tennessee, attracted more than forty thousand awestruck visitors a year—but for the most part, the clientele for the hillbilly hoedowns and the cave tours tended not to be drawn from Loughborough’s social set.

So too the friends and neighbors who would come to seek relief from the summer heat within the cooling radius of Blowing Cave—ambling and searching, in this case, for the cheapest form of air-conditioning around.5

In the mid-1970s, archeologists were not the only outsiders poking around in the caves of Fentress County. Over the course of a week in August 1975, some thirty agents with the Federal Bureau of Investigation combed the rugged hills and winding creek beds that run through the northern part of the county, near the small, unincorporated community of Pall Mall, which locals pronounce pal-mal and whose most notable offspring remains Sergeant Alvin C. York, of World War I fame by way of Gary Cooper. The agents were looking for Billy Dean Anderson, another native son of Fentress County and at that time a recent addition to the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list. And they were looking there because it was, the Bureau claimed, “a remote, mountainous area inhabited principally by moonshiners, bootleggers, and other outlaws.”6

Indeed, in addition to their more quotidian social functions as root cellars and rural churches and outdoor dance halls, caves had long served as extralegal or outlaw spaces across the South. Armed guerillas, both Confederate and Unionist in their sympathies, had launched murderous attacks on each other from Fentress County’s caves during the war years, and stored plunder there following successful raids. Throughout the region, whiskey stills and bottles of moonshine were far more common cave floor discoveries than prehistoric footprints, and would continue to be for decades after the end of Prohibition. Jesse James and his gang were known to hide out in a system of caves in the Missouri Ozarks that stretched for more than four miles underground; according to legend, when one unlucky sheriff thought he had the Jameses cornered, he ended up waiting in vain outside one entrance to the Meramec Caverns while the gang used the network of passageways to slip out another exit. More than a century later, Eric Rudolph, the anti-abortionist behind the bombing at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta as well as a string of other bombings across the southeastern United States in the late 1990s, avoided capture in the caves of the remote Blue Ridge Mountains for nearly seven years, until a police officer happened upon him rummaging in a dumpster behind a Save-a-Lot in Murphy, North Carolina.7

Throughout the region, whiskey stills and bottles of moonshine were far more common cave floor discoveries than prehistoric footprints, and would continue to be for decades after the end of Prohibition.

Decked out in hiking boots and climbing gear, the FBI agents spent days searching a half dozen caves around Pall Mall, including Blowing Cave, but came up empty. “For the most part these caves have mud floors, are damp or wet, and have an average temperature of around fifty or fifty-five degrees,” the Bureau’s report noted. “In addition, a short distance inside the caves, there is total darkness.” It was well-known that Anderson was capable of living “practically like an animal”; nevertheless, the FBI concluded, “searches of these caves revealed conclusively that [they] had not been used for human habitation.”

As it turned out, Billy Dean Anderson actually was hiding in a cave, and just a few miles away from where the FBI agents went looking for him that August. He had been living there for much of the past year, ever since escaping the county jail in Wartburg where he was awaiting trial for his role in a botched 1973 nightclub robbery that left a sheriff’s deputy with a permanently disabling shotgun wound in the arm. (It was not the first time that Anderson had committed a robbery, or fired a gun at police officers, or broken out of jail.) And he would live there for the next four years, aided and abetted by friends and family in the area, who brought him food and writing materials (he kept a diary) and painting supplies (Anderson was also an amateur painter, specializing in pastoral scenes from nature and the Bible) while his face was plastered on post office bulletin boards from Miami to Los Angeles. “The fugitive is reportedly somewhat of a ‘folk hero’ in the area,” the FBI grumbled, as the manhunt dragged on. Despite their fruitless week of caving, the Bureau remained convinced that Anderson was hiding out close to home. Before long, they had begun referring to him as “The Mountain Man.”

Ultimately, a lucky break would lead the FBI to track him down in July 1979, when agents ambushed Anderson outside of his mother’s farmhouse and killed him in a hail of gunfire. Ben King, a Fentress County musician, was playing a show at a little beer joint called Top of the Mountain, on U.S. Highway 127, the night Anderson was killed; he remembers standing outside with the bar’s owner, watching local deputies close down the road going in and out of the valley where Anderson’s mother lived, in preparation for the ambush. “Make no mistake, Billy Anderson was a sociopath of the highest order,” King recalls. “But he never killed anyone. That was part of his mystique.” A few days later, King wrote a song about Anderson, which he would perform around the area in the years to come, whenever he found himself in front of an audience familiar with the local tragedy.

Aw, Billy, don’t come home tonight, son.

There’s thirteen men out there, and every one of them has a gun.

They’re gonna kill you, Billy, cause while you’re alive,

You’re hard on their reputation, you hurt their pride.8

In 1976—a couple years into Billy Dean Anderson’s time as a fugitive, and just as archeologists were beginning to understand the nature of their discovery at Blowing Cave—RCA released Wanted! The Outlaws, a compilation album featuring songs by Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Tompall Glaser, and Jessi Colter. Despite all the material on the album having been released previously, The Outlaws quickly rose to the top of the country charts, and two tracks from the album—“Good Hearted Woman,” recorded by Jennings and Nelson; and “Suspicious Minds,” by Colter and Jennings—became the number one and number two country singles, respectively. Buoyed by a massive publicity campaign orchestrated by RCA, which had seen Nelson’s Red Headed Stranger sell a million copies for Columbia the year before and was eager to replicate that album’s remarkable success, The Outlaws even made it into the top ten on the pop charts. By the end of the year, it would become country music’s first ever platinum-certified record.9

The Outlaws was the commercial (if not quite the critical) apotheosis of the “outlaw country” movement of the 1970s, and, like Red Headed Stranger, the album was preoccupied with men and women (though mainly men) who lived outside the bounds of society. Outlaws themselves, of course, had always figured importantly in the country music songbook. Vernon Dalhart’s “The Prisoner’s Song” and Henry Whitter’s “Lonesome Road Blues,” both released in 1924, had been among the earliest hits in the genre’s recorded history, and the rambling man—a character of dubious morals and no discernible social attachments—had been a constant across the generations, appearing repeatedly in the music of Jimmie Rodgers, Hank Williams, Merle Haggard, and many lesser lights besides.10

Now if I had wings like an angel / Over these prison walls I would fly.

But where those familiar numbers could be known to verge into maudlin exercises in a Christian allegory of redemption and transcendence (“Now if I had wings like an angel / Over these prison walls I would fly”), the outlaw recordings of the 1970s unrepentantly populated a gothic landscape with enough silver-tongued devils, mysterious rhinestone cowboys, and men dressed in black to make Ambrose Bierce or at least Damon Runyon proud. (Who else could have come up with names like Good Time Charlie, Willy the Wandering Gypsy, and a woman called Codeine who fancies herself “the cream of the Basin Street queens”?) Nelson’s eponymous stranger goes “wild in his sorrow” after learning that his wife has been unfaithful, and proceeds to ramble across the Mountain West on a killing spree: “Don’t fight him, don’t spite him, just wait til’ [sic] tomorrow / maybe he’ll ride on again.” And he was only the first among many in a rogue’s gallery of rejects and ne’er-do-wells, hatched from the American underbelly and poured forth from the imaginations of the outlaw singers and songwriters. Bandit boys who wear their guns on their hip, “for all the honest world to feel.” Mothers who are always looking for a lover. No-account boozers. Desperadoes waiting for a train. Greyhound bus riders.11

“On a Greyhound bus,” in fact, is the opening lyric of Waylon Jennings’s 1973 album Lonesome, On’ry and Mean—a mid-gallop scene setter for a record that, in a way, formally inaugurated the outlaw country moment. At root, the outlaw recordings were an industrial statement as much as they were an aesthetic one: a collective rejection of the major studios’ stranglehold on the output of their working musicians (many of whom were still making shockingly little in royalties, despite their growing sales figures), and the cookie-cutter standardization imposed on mid-century country-pop that had turned Music Row into a southern variation on Tin Pan Alley. Lonesome was the first record that Jennings released after renegotiating his contract with RCA, and the unprecedented creative control that he was able to secure over how his music was produced and recorded set a standard that other outlaws against the Nashville establishment were quick to emulate. It was during these years also that the outlaws increasingly made a point of working with their own, like-minded producers, like “Cowboy” Jack Clement; and of recording at independent studios like the one Tompall Glaser and his brothers opened in the heart of Music Row and informally referred to—middle-finger definitely implied—as Hillbilly Central. Willie Nelson did them one better: he not only tore up his own contract with RCA, he left Nashville behind altogether and hit the road for the more liberal environs of Austin, Texas, where he was greeted with open arms by the longhairs and rednecks and cosmic cowboys at the Armadillo World Headquarters. On a Greyhound bus, indeed.12

So here was another sense in which the outlaw recordings departed from the old standards. Nelson, Jennings, and the rest not only wrote and recorded songs about outlaws; they identified themselves as and with outlaws as well. In place of the there-but-for-the-grace-of-God moralizing of a Vernon Dalhart or a Henry Whitter—or even the woe-is-me self-pity of a Hank Williams—here was Kris Kristofferson crowing about beating the devil at his own game, and Jennings whooping it up about “honky-tonk heroes like me.” To be sure, this was all a good measure of show-biz gimmickry, as one look at the faux Wild West “Wanted” poster that graced the album cover for The Outlaws made clear. But even as a marketing ploy, the outlaws stood in stark contrast to the smoothed-over edges of the “countrypolitan” artists, like Patsy Cline, George Jones, and Glen Campbell, who had ruled the country charts since the late 1950s and whose clean-cut packaging seemed to angle more for bourgeois respectability than hillbilly authenticity. If that was what the “honest world” represented, then the outlaws were prepared to light out for the territories—or, perhaps more to the point, for the subterranean spaces that had always been the refuge of the fugitive and the convict, the hippies and the deadbeats, the drifters and the drunks.13

The outlaws stood in stark contrast to the smoothed-over edges of the “countrypolitan.”

Former folkie-cum-Austin confrere Jerry Jeff Walker, whose songs often captured the countercultural irreverence which typified the outlaw movement, once described his rebellion against the Nashville studio system this way: “Whenever someone mentioned ‘studio,’ I hid, I bought another round, and I looked for a hole to disappear into.”14

Of all the outlaws, none pushed as hard against the bounds of bourgeois respectability as David Allan Coe. Coe was born in Akron, Ohio, in 1939. His father, Donald, was a twenty-five-year-old unskilled laborer who found on-again, off-again work in the rubber industry. (Akron, then known as “Rubber City,” contained the largest concentration of rubber manufacturing stock on the globe in the decades between the world wars.) His mother, Dorothy, was thirty-four and stayed at home. Class divisions in Akron at the time were relatively simple. As one contemporary observer put it, “The ruling class, the upper crust, the rich and prosperous” consisted almost entirely of the city’s older and long-tenured residents, many of whom worked in professional or executive capacities attached to the rubber industry. The remainder of the city had “come in from underneath, as workers.” The Coes came in from underneath: Donald made just $340 the year David was born, about one quarter of the average household income at the time.15

I’ve been sawing on these bars so long I want to shout.

Always a gifted songwriter, Coe’s most confounding invention was often himself. He spent much of his adolescence and young adulthood in one correctional facility or another. Although the most serious crime he was ever charged with was possession of burglary implements (a screwdriver), when he later became a star he would insist with journalists that he had also killed a man while in prison. (Pressed on the details, Coe would give explanations like the following: “If they exonerate me of any crimes like they did Nixon, maybe I’d tell about it.”) His debut album, Penitentiary Blues, released in 1970 by the independent Plantation Records, was pure jailhouse blues-rock: “I’ve been sawing on these bars so long I want to shout / I’m getting out of this place soon, of that there is no doubt.” But by the time he signed his first major-label deal with Columbia, he had reimagined himself as The Mysterious Rhinestone Cowboy, a swaggering stage persona that fell somewhere between outlaw country machismo (chaps, cowboy hat) and Village People vamping (Lone Ranger mask, flowing wig, head-to-toe costume jewelry; according to Dorothy, David had preferred to wear dresses until the age of seven).16

The record-breaking success of Wanted! The Outlaws had made it clear to all concerned that there was money to be made in the music of cultural rebellion. Yet while Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings were cashing in with new recording contracts and movie deals (anticipatory down payments on the Grammy Awards and even, in Nelson’s case, Kennedy Center Honors to come), there was always a little too much of a taste for the insubordinate in David Allan Coe originals like “Take This Job and Shove It”—a song he wrote during a temporary retirement, after burning out on performing—or “I’d Like to Kick the Shit Out of You”—a song he once dedicated to a journalist from Rolling Stone. By the end of the 1970s, he was riding around with a motorcycle gang and releasing a pair of so-called “underground” albums, whose lyrics were alternately so crassly obscene, cruelly misogynistic, or vilely racist (one track was called “N*****r Fucker”) that The Guardian would later give Coe the dubious honor of selecting them among the most offensive albums of all time.17

If, as The Mysterious Rhinestone Cowboy himself once put it, “a singer is just an actor playing the part of a singer,” Coe seemed intent on playing the part of the outlaw with all the conviction of a Strasberg Method devotee. But others have argued that there was more than just an act to Coe’s performance. Nadine Hubbs, a musicologist and gender studies scholar, has written compellingly of the disruptive power of Coe’s music—its “working-class deviance and irreverent, noneuphemistic resistance”—most notably in a song included on the underground albums called “Fuck Aneta Briant.” “Fuck Aneta Briant” excoriates the gay-bashing icon of the Christian Right (even going so far as pointedly misspelling her name), for “telling all them f*****s that they can’t be free.” And it does so while evincing an unmistakable familiarity with—even appreciation for—the variety of socio-sexual roles that male inmates take on in prison. Coe’s song, Hubbs argues, “refuted the authority of those who would judge certain debased groups in society as worthless and expendable,” and it did so in a way that articulated a “shared social position of disreputability and marginality” which encompassed the multiple and overlapping outlaw identities Coe took on: redneck, ex-con, shit-kicker, Rhinestone Cowboy—even vulgar bigot. These and other sins against propriety defined the antibourgeois impulse at the heart of Coe’s music—what made it somehow, and all at once, both more radical and more reactionary than anything else that came out of the outlaw movement.18

Coe seemed intent on playing the part of the outlaw with all the conviction of a Strasberg Method devotee.

Like other outlaws before him, Coe made enemies in the honest world that he couldn’t shake, among them the IRS. After the federal government repossessed his home for unpaid taxes in 1990, a rumor began to spread, despite absolutely no proof of its veracity, that Coe had taken to living in a cave in Tennessee. Like the prison murder story before it, this one was likely false, a creation of Coe’s myth-making appetite for inflating his own rap sheet. Nevertheless, the story continues to circulate today, on fan sites and discussion boards and even in the occasional concert review or profile.19

So far as it is possible to tell, the story took wing when it did thanks only to the thinnest of pretexts: that for a few years in the 1980s, Coe had owned an eighty-acre resort in Dickson County, west of Nashville, which had once, many years prior, been home to a colony of utopian socialists, who had liked to hold outdoor concerts in a giant hole in the ground they named for John Ruskin.20

In 1982, in response to a request from a curious Duke University librarian who also happened to edit the professional journal Library Acquisitions: Practice & Theory, David Allan Coe compiled a list of recommendations for what books and other reading material he thought should be included in a prison library. The list included twenty-three specific titles (among them one book by Dostoyevsky, one book by Hemingway, and two books by David Allan Coe); a half dozen more generic suggestions (“books on income tax”); and Oscar Wilde’s “The Ballad of Reading Gaol,” published in 1898, after the Irish poet and playwright had spent two years in a London prison for committing acts of what the British Parliament had recently taken to euphemizing as “gross indecency.”21

Like Wanted! The Outlaws in its own way, “Reading Gaol” is one of its author’s more widely circulated yet less critically beloved works, a rare and perhaps only partially successful exercise in a more “popular” and sentimental verse style on the part of the arch-Aesthetic. Yet it is not hard to see why it would appeal to Coe (who, it bears mentioning, appears to be such a longstanding if unexpected Oscar Wilde fan that he even named a song after him: Penitentiary Blues’s “Cell #33,” which invokes the alphanumeric code for Wilde’s own cell at Reading Prison—cell block C, landing 3, cell 3—that not only provided Wilde with his prison identification number—C.3.3.—but also the pseudonym under which he first published “Reading Gaol” after his release.) The poem revolves around the case of a young member of the Queen’s Guard, who, while in a fit of passion—“blood and wine were on his hands”—kills the young woman he loves. But rather than mere murder ballad, Wilde intends “Reading Gaol” as a poem of protest. Sentenced to die, the guardsman comes to embody the essential inhumanity of an unforgiving penal system in the eyes of the poem’s narrator, the fellow prisoner who had been Wilde. “They hanged him as a beast is hanged,” laments the narrator, “and hid him in a hole.” Mocked by his officious jailers (who “wore their Sunday suits”), unblessed by the prison chaplain, the guardsman is outcast even in death—his only mourners, in the end, the other outcasts behind the penitentiary walls.22

They hanged him as a beast is hanged and hid him in a hole.

There is another reading of Wilde’s poem, however, which also seems to shed some light on Coe and his fellow musical outlaws. Distraught wife-killers like the guardsman were depressingly familiar figures in the repertoire of the outlaw singers: men who, like the Red Headed Stranger, acted out of a passion that was so intense that it became somehow honorable, or natural, or tragic—or, if nothing else, manly. A crime has been committed; there is a body. And yet, Wilde’s sympathies lie so totally with the killer that he becomes the poem’s true victim. Given the nature of his own persecution at the hands of an intolerant, moralistic, and hypocritical state, it is understandable why Wilde might see a Christ-like resonance in one of its fellow sufferers. But there is something fundamentally casuistic behind the implication that because a system is corrupt and even immoral, those who act against its rules and norms are necessarily moral and just. “Reading Gaol” is sentimentalist—and more than that, it is a cop-out, an eleventh-hour reprieve for another red headed stranger who might, ultimately, just not deserve it.

The outlaw country movement of the 1970s contained both of these tendencies within it as well—a rebelliousness that was sometimes righteous and at other times arrogant, self-serving, even obscurantist. It made heroes out of figures who bucked the system, regardless of their rationale for doing so or the consequences of their words and deeds. From the clutches of mid-twentieth century embourgeoisement, it attempted to salvage a kind of rough populism which had always been present in country music, and which had always had both leftist and rightist articulations: an instinct to elevate the poor and downtrodden common folk of the rural South, to make a music of their lives and struggles and desires (even their most illicit ones); and an impulse to do so by closing themselves off behind the parochialisms of the old order of things. At the end of the day, Eric Hobsbawm once wrote, a bandit is “merely a dream of how wonderful it would be if times were always good.” No wonder, then, that so many outlaw singers at least dipped their toes in Confederate romanticism.23

A bandit is “merely a dream of how wonderful it would be if times were always good.

In Fentress County, locals were divided on the question of the Confederacy. The county’s two representatives in the Tennessee General Assembly, Reese Hildreth and R. H. Bledsoe, voted for secession in 1861; the county at large, composed overwhelmingly of small farmers and home to few large slaveholdings, voted against, by a margin of more than five to one. “Feeling in that border area was very bitter during and for some time after the Civil War,” recalled Cordell Hull, a native of neighboring Pickett County who would go on to become Franklin Roosevelt’s Secretary of State.24

A little more than a century later, the county was also split on the question of Billy Dean Anderson. “Some say he was the kindest person that they had ever met,” one local newspaper reported in the winter of 1979, a few months before someone tipped off the feds to his whereabouts. “Others will tell you he’s the meanest man that ever walked the face of the earth.”25

Not long after that, Ben King sat down to write a country music song.

Billy Dean,

Sleeping in a cave, living off the land,

Hunted night and day, you were a lonely man.

This essay first appeared in the Music & Protest issue (vol. 24, no. 3).

Max Fraser was named a finalist for the 2018 Allan Nevins Prize, awarded by the Society of American Historians. He is currently a fellow at the Society of Fellows at Dartmouth College, where he is finishing a book about what Steve Earle once called the “hillbilly highway.”NOTES

- P. Willey et al., “Preservation of Prehistoric Footprints in Jaguar Cave, Tennessee,” Journal of Cave and Karst Studies 67, no. 1 (April 2005): 63. For another poignant description of an experience “ambling and searching” in the caves of Tennessee (in this case, an amphetamine-enhanced one), see the 2003 interview with Johnny Cash published in this journal: Johnny Cash, “You Have to Call Me the Way You See Me,” Southern Cultures 21, no. 3 (Fall 2015): esp. 10–11.

- Associated Press, “Human Footprints from 4,500 Years Ago Found,” October 2, 1983.

- Jay D. Franklin, “Excavating and Analyzing Prehistoric Lithic Quarries: An Example from 3rd Unnamed Cave, Tennessee,” Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 26, no. 2 (Fall 2001): 199–217; and Joseph C. Douglas, “Minerals, Moonshine, and Misanthropes: The Historic Use of Caves in the Upper Cumberland,” in Rural Life and Culture in the Upper Cumberland, eds. Michael E. Birdwell and W. Calvin Dickinson (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2004), 15–34.

- A Lady [Mary Ann Loughborough], My Cave Life in Vicksburg, with Letters of Trial and Travel (New York: D. Appleton, 1864), 78, 114, 118.

- W. Fitzhugh Brundage, A Socialist Utopia in the New South: The Ruskin Colonies in Tennessee and Georgia, 1894–1901 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1996); and Ruth Nichols Keenoy and Robbie D. Jones, “Caving and Clogging: Keepin’ Cool in Tennessee’s Caves,” in Looking Beyond the Highway: Dixie Roads and Culture, eds. Claudette Stager and Martha Carver (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), 167–184.

- The FBI case notes and reports cited in this section are quoted at length in Kay Wood Conatser, Billy Dean Anderson: A Criminal Life (self-published, 2013), and currently remain in that author’s possession. For more background on Anderson, see William Lynwood Montell, Killings: Folk Justice in the Upper South (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1986), 138–143; and Montell, “‘That’s Not the Way I Heard It’: Traditional Life and Folk Legends of the Upper Cumberland,” in Rural Life and Culture in the Upper Cumberland, eds. Birdwell and Dickinson, 122–139.

- Pat Strickler, “The Jesse James Legend (cont’d.),” Life, June 12, 1970, 72; Allan Gurganus, “Why We Fed the Bomber,” New York Times, June 8, 2003, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2003/06/08/opinion/why-we-fed-the-bomber.html, accessed May 29, 2018.

- Email communication with Ben King, December 6, 2017; lyrics to Ben King’s unpublished song “Billy Dean” are in author’s possession.

- Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Jessi Colter, Tompall Glaser, Wanted! The Outlaws, RCA Victor AAL1-1321, 1976; Bill C. Malone, Country Music, U.S.A., rev. ed. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985); and Chet Flippo, “From the Bump-Bump Room to the Barricades: Waylon, Tompall, and the Outlaw Revolution,” in Country: The Music and the Musicians, eds. Paul Kingsbury, Alan Axel-rod, and Susan Costello (New York: Abbeville Press, 1994), 312–327.

- “The Prisoner’s Song,” Vernon Dalhart, Victor 19427-B, 1924; “Lonesome Road Blues,” Henry Whitter, OKeh 40015, 1924.

- “The Prisoner’s Song”; “Pancho & Lefty,” track 8 on Townes Van Zandt, The Late Great Townes Van Zandt, Poppy LA004-F, 1972; “Lonesome, On’ry and Mean,” track 1 on Waylon Jennings, Lonesome, On’ry and Mean, RCA LSP-4854, 1973; and “Red Headed Stranger,” track 6 on Willie Nelson, Red Headed Stranger, Columbia KC 33482, 1975.

- On the Outlaw movement broadly, see Michael Bane, The Outlaws: Revolution in Country Music (New York: Doubleday, 1978), and Michael Streissguth, Outlaw: Waylon, Willie, Kris and the Renegades of Nashville (New York: IT Books, 2013). On the Austin music scene, see Archie Green, “Austin’s Cosmic Cowboys: Words in Collision,” in “And Other Neighborly Names”: Social Process and Cultural Image in Texas Folklore, eds. Richard Bauman and Roger D. Abrahams (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981), 152–194; Stephen R. Tucker, “Progressive Country Music, 1972–1976: Its Impact and Creative Highlights,” Southern Quarterly 22, no. 3 (Spring 1984): 93–110; as well as the more recent work noted below.

- “To Beat the Devil,” track 2 on Kris Kristofferson, Kristofferson, Monument SLP18139, 1970; “Honky Tonk Heroes,” track 1 on Waylon Jennings, Honky Tonk Heroes, RCA APL1-0240, 1973. Nashville’s quick commoditization of the outlaw movement, embodied in the made-to-order success of The Outlaws compilation album, was itself one of the motivating factors in the more anti-establishment impulses animating the so-called “progressive country” movement, which took shape simultaneously in and around Austin. For more on the distinctions between Tennessee and Texas brought to the foreground by the outlaws and their fellow travelers, see especially Travis D. Stimeling, Cosmic Cowboys and New Hicks: The Countercultural Sounds of Austin’s Progressive Country Music Scene (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), and Jason Mellard, Progressive Country: How the 1970s Transformed the Texan in Popular Culture (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013). Still, as Bill Malone pointed out some time ago, the outlaws’ “rebellion” from and against mainstream country music was a fundamentally fraternal one, “at base little more than an effort to assert their artistic independence within the confining context of a corporate musical structure.” The key word there is within, since as Malone and others have pointed out, the quite mainstream, thoroughly commercial success the outlaw movement ended up enjoying “did more to preserve a distinct identity for country music than most of their contemporaries who wore the ‘country’ label.” Malone, Country Music, U.S.A., 404–405.

- For Walker’s countercultural irreverence, see especially “Up Against the Wall, Redneck Mother,” track 6 on Jerry Jeff Walker, Viva Terlingua, MCA Records MCA-382, 1973. The quote above is from the liner notes to Jerry Jeff Walker, Jerry Jeff Walker, Decca DL 7-5384, 1972, and is reproduced in Tucker, “Progressive Country Music,” 101. For an exceptional discussion of the Viva Terlingua recording sessions, as a window into the cultural and ideological divides separating the country scenes in Austin and Nashville during this period, see Stimeling, Cosmic Cowboys and New Hicks, ch. 4.

- The information about Coe’s family is taken from the original worksheets of the 1940 Census, which are available online at “1940 Census,” National Archives, accessed May 29, 2018, https://1940census.archives.gov/index.asp. The description of Akron appears in Alfred Winslow Jones, Life, Liberty, and Property: A Story of Conflict and a Measurement of Conflicting Rights (Philadelphia: J. P. Lippincott, 1941), 67–68.

- “Cell #33,” track 2 on David Allan Coe, Penitentiary Blues, SSS International SSS-9, 1969; David Allan Coe, The Mysterious Rhinestone Cowboy, Columbia KC 32942, 1974; and Larry L. King, “David Allan Coe’s Greatest Hits,” Esquire, July 1976, 71–73, 142–144.

- David Allan Coe, “Nothing Sacred,” D.A.C. Records LP-0002, 1978; and David Allan Coe, Underground Album, D.A.C. Records LP-0003, 1082. On the writing of “Take this Job and Shove It,” which became a hit for the outlaw country singer Johnny Paycheck after he recorded it in 1977, see Dorothy Horstman, Sing Your Heart Out, Country Boy: Classic Country Songs and Their Inside Stories by the Men and Women Who Wrote Them, rev. ed. (Nashville: Country Music Foundation Press, 1996), 323. For a sense of the outcry provoked by the underground albums, see Neil Strauss, “Songwriter’s Racist Songs from 1980s Haunt Him,” New York Times, September 4, 2000, E1; and Angus Batey, “What is the most offensive album of all time?,” The Guardian, October 21, 2010, accessed May 29, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2010/oct/21/offensive-albums-ice-cube-david-allan-coe.

- Coe quoted in Denise Edgington, “The Reddest Neck in Town,” Houston Press, May 30, 2002. Hubbs’s discussion of Coe’s music appears in Nadine Hubbs, Rednecks, Queers, and Country Music (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014), quoted here at 7, 153. Equally strong discussions of the gendered discourse in outlaw country music (and white southern musical culture more broadly)—particularly the role played by a performative, if at times multivalent, masculinity—can be found in Ted Ownby, “Freedom, Manhood, and White Male Tradition in 1970s Southern Rock,” in Haunted Bodies: Gender and Southern Texts, eds. Anne Goodwyn Jones and Susan V. Donaldson (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1997): 369–88; Jason T. Eastman, “Rebel Manhood: The Hegemonic Masculinity of the Southern Rock Music Revival,” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 41, no.2 (2012): 189–219; Travis D. Stimeling, “Narrative, Vocal Staging and Masculinity in the ‘Outlaw’ Country Music of Waylon Jennings,” Popular Music 32, no. 3 (2013), 343–358; and Mellard, Progressive Country, esp. ch. 4. The argument I offer here about the gendered subtexts in the outlaw recordings has benefited from all of these readings—but most notably from Hubbs’s writing on Coe.

- See, for instance, “10 Badass David Allan Coe Moments,” savingcountrymusic.com, accessed May 29, 2018, https://www.savingcountrymusic.com/10-badass-david-allan-coe-moments-75th-birthday-special/.

- Keenoy and Jones, “Caving and Clogging,” 177.

- “Acquisitions for Prison Libraries: A Selected Bibliography, by David Allan Coe, and a Response, by Christine L. Kirby,” ed. Susan McDonald, Library Acquisitions: Practice & Theory 7, no. 1 (1983): 29–33.

- Of course, it is possible that Coe had a more personal connection to a “Cell #33” that dated to his own years spent in various detention centers. One way or another, though, the number clearly had a special significance to him as well as to Wilde: Coe’s third album, The Mysterious Rhinestone Cowboy, includes a track called “The 33rd of August”—which, it just so happens, is another song sung from a jail cell. “The 33rd of August,” track 4 on David Allan Coe, The Mysterious Rhinestone Cowboy; Oscar Wilde, “The Ballad of Reading Gaol,” in The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde: Stories, Plays, Poems, and Essays (New York: Perennial Library, 1966; London: Collins, 1989), 843, 854, 856. The first six editions of the poem, published between February 1898 and May 1899, all listed the author as “C.3.3.” on the title page; although the author’s identity was hardly a secret by that point, it was only with the seventh edition, published in June 1899, that the publisher included “Oscar Wilde” on the title page as well. Richard Ellman, Oscar Wilde (New York: Vintage Books, 1988), 526.

- There is a rich through line on the themes of authenticity, working-class identity, and outsider-hood in country music scholarship; see, among others, Richard A. Peterson, Creating Country Music: Fabricating Authenticity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997); Bill C. Malone, Don’t Get above Your Raisin’: Country Music and the Southern Working Class (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002); Barbara Ching, Wrong’s What I Do Best: Hard Country Music and Contemporary Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001); Aaron A. Fox, Real Country: Music and Language in Working-Class Culture (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004). Hobsbawm is quoted in Primitive Rebels: Studies in Archaic Forms of Social Movements in the 19th and 20th Centuries (New York: Free Press, 1959; New York: Norton, 1965), 25.

- Mary Emily Robertson Campbell, The Attitude of Tennesseans toward the Union, 1847–1861 (New York: Vantage Press, 1961); James B. Jones Jr., “‘Fevers Ran High’: The Civil War in the Cumberland,” in Rural Life and Culture in the Upper Cumberland, eds. Birdwell and Dickinson, 73–104; and Cordell Hull, The Memoirs of Cordell Hull (New York: Macmillan, 1948), 7.

- Clinton County News, quoted in Conatser, Billy Dean Anderson, 126.