Land of the sweet, never sour, Sugar Land, Texas, offers a surburban alternative outside the expanding Houston area.1 The city has gone by many names. In 1838, two years into the Republic of Texas’s victory over the Republic of Mexico, what is now Sugar Land was named the Oakland Plantation. Stephen F. Austin (the “Father of Texas”) gave land to businessman and administrator Samuel May Williams as payment for his work providing land grants as incentives to bring white settlers to the new republic. In 1853, Williams sold the plantation to his brothers, Nathaniel and Matthew Williams. Together, they combined the plantation with adjoining lands and renamed it Sugar Land. The late 1800s brought a new nickname to Sugar Land among the city’s convict laborers: “Hell Hole on the Brazos.” Sugar Land’s infrastructure expanded in the decades following the end of convict leasing in 1912, resulting in the erasure of the city’s histories of Black and Indigenous removal. The city’s wealth—held almost exclusively by its white business owners, former plantation owners, and political elites—grew thanks to sugar tours, school field trips to the humid banks of the Brazos River, and the wealth generated by sugar production. These legacies of violence, swallowed by the earth and long buried, were unearthed in 2018 when developers disturbed the dirt underneath the city.2

Texas has buried its history rather well. Sugar Land is land of the Karankawa and Tonkawa tribes, which gathered at the now commercial banks of Sugar Land’s Oyster Creek and Brazos River. Oakland Plantation began with Indigenous removal and the sinister capitalism that maintained brutal control over Black bodies forced to do hard labor. These were the legacies of plantation violence and its afterlives during the Civil War and Reconstruction.3

The Williams brothers used Oyster Creek to build a commercial sugar mill, and on Oakland Plantation they forced enslaved people to harvest sugarcane. After the area had been renamed Sugar Land, the city’s penal system began under former Confederate colonel Edward H. Cunningham (also known as the “Texas Sugar King”). It was during this time, when convicts were leased out to work privately owned land, that Sugar Land became known as the Hell Hole on the Brazos. Over the years, more and more privately owned plantation land was transferred to the state, a profitable move that allowed Texas to maintain the city’s economic growth while continuing to benefit from the people generating that growth: Black prison laborers.4

Much of the state’s Black history remains difficult to find, often having been relegated to small rural museums. Not to mention that the narrative Texas condones in its education system neglects discussion of enslavement, plantation lives, and prison farms. But Black Texas offers alternative archives mostly unreliant on documents and museum space. These alternatives thrive in orality, testimony, folklore, music—and dirt.5

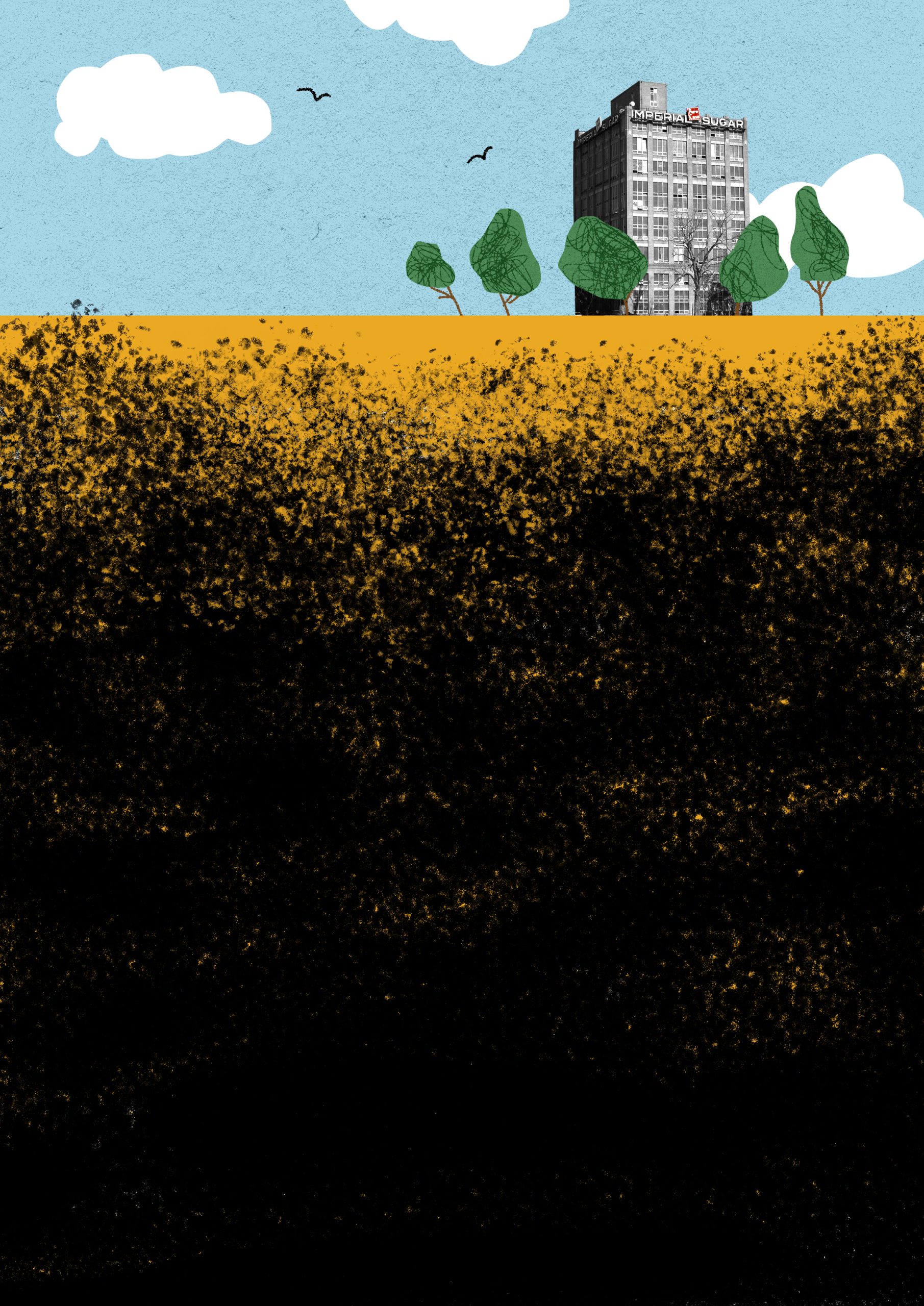

In April 2018, construction workers came across ninety-five sets of remains at the site of what was intended to be the $59 million career and technical center for Fort Bend Independent School District (FBISD). This piece of land under construction was once the Imperial Sugar Company headquarters. Fort Bend County and its neighboring counties, Matagorda, Wharton, and Brazoria, formed the “Sugar Bowl of Texas” for centuries courtesy of the Williams brothers. It is estimated that the people in this unmarked cemetery, estimated to have been buried between 1878 and 1911, ranged from fourteen to seventy years old when they died. Their discovery immediately interrupted the construction of FBISD’s center. Washington Post reporter Meagan Flynn noted that signs of “repetitive wear” engraved on each of these Black bodies “indicat[ed] hard labor.” That wear marked the statewide funding of plantations-turned-prison-farms for Black convicts.6

To recognize that we have been living alongside the dead means reshaping our relationship to Texas dirt. The breadth of Black death, unearthed, shifts how we understand Black Texas histories in Sugar Land. Katherine McKittrick describes the built knowledge and geographies that we find ourselves bound to as “familiar plot[s].” But looking beneath Sugar Land’s built environment—one that thrives on consumption and neglect—allows us to imagine the city in a different way. The history of sugar’s infrastructure cannot exist apart from state-sanctioned violence, apart from engraved shackles on flesh. By looking at Texas dirt anew, I wish to explore what it has meant for me and other Black Texans to confront this place’s haunting by former prison laborers and plantation slaves. What is the vantage point of the dead and what is their history? In its quest for an empire built on sugar, Sugar Land has consumed Black flesh and buried its remains in its infrastructure under the guise of progress. But dirt preserved the visceral realities of early Black life in Sugar Land. Unearthing what Sugar Land’s dirt holds brings Texas’s invisible geographies to light, allowing us to imagine an alternative archive made over time in Sugar Land. New ways of knowing emerge when we dig below Sugar Land’s industrial legacies—when, instead of eating the sugar it produces, we consume the contents of the city’s underground archive. My own memories, and the markings of the prison laborers, demand this shift.7

The breadth of Black death, unearthed, shifts how we understand Black Texas histories in Sugar Land.

I was called to the ground early in life. Ground was familiar, a source of meaning-making present in family stories, a reminder under my fingernails of learning how to unearth potatoes and peas, a lingering trace in pots of greens. Yet, my grandfather told me that the ground was not ours, that what was once our legacy had been taken, bought, and stripped. Ground—and, more specifically, dirt—was contentious for me, an idea that Katherine McKittrick illuminates: “If the earth has skin, then the dirt is its memory.” The discovery of the Sugar Land 95 moved me toward a deeper understanding of Texas memory.8

For seven years, I attended a private Christian high school in Sugar Land. The Imperial Sugar Company was a three or so minute drive from the school, and I remember staring at the large building immediately behind the railroad tracks off Highway 90. It was abandoned but the huge Imperial Sugar Factory sign remained. I have used that brand of sugar in cooking, baking, and memory-making. I was curious about what it looked like inside, who worked there, what stories it held. What would this factory tell me about the history of the sugar I used? In 2015, there were whispers that the land on which the Imperial Sugar Factory stood might be torn down to make room for an advanced technical center for surrounding high schools (many of which are predominantly white). My school community was excited about the possibility of witnessing its destruction (while planning last tours, last observances). With each drive past the sign, I savored what I believed to be my final views of its mystery. But amid this place’s troublesome grounds, I continued to eat dirt, uncertain whether I would find Black Texas history in Sugar Land.

The discovery of the Sugar Land 95, as they came to be known, uncovered a new sense of Texas space. Dirt has been a means of sustenance, cultivated and contested, a site of economic and ideological possession—but the 95 necessitated an alternate reading of Sugar Land’s spatial origins. Dirt is what sociologist Avery F. Gordon calls a “social figure,” a haunting presence that exists in the intimate margins between life and death. The dirt is messy, revealing much of what I do not know while also revealing that I know too much about my home space. Digging in the dirt and reflecting upon this city space showed me that my Blackness did not belong. Digging meant unburying the lie that enslavement did not reach Texas. Two years of required Texas history across middle and high school failed to teach us that Black Texans were the last to know that slavery had ended, a moment now marked by the annual celebration of Juneteenth. In fact, I learned about Juneteenth celebrations in communion with my family, when we sat at picnic tables outside, bare feet shuffling in red dirt, and ate barbecued ribs and pieces of brisket. Those experiences built a history separate from the one advertised by Fort Bend County and its private schools. When I entered graduate school, I attempted to make my own archive focused on learning about enslavement along the Gulf Coast. I never looked farther west than Louisiana; I didn’t know that Southeast Texas was known for its sugar cane production. Little is known of those sugar plantations my parents’ home now sits on, the ground I walked for school, or the dirt my toddler sister and brother once found so enjoyable to consume unknowingly. Dirt archives the lives of the buried, preserving their difficult truths and complicating, if not dismantling, dominant histories built above ground. Dirt allows me to see beneath Texas history to recover the stories of the wronged and forgotten.9

The dirt is messy, revealing much of what I do not know while also revealing that I know too much about my home space.

This mass grave site contained not just the misshapen bones of prison laborers, but also those of the formerly enslaved. According to news reports, many bodies were buried in chains and with the tools of their livelihoods. As I speculate about the unspoken lives of those bones, I imagine a girl or woman—perhaps only fourteen—sent to labor on a plantation. What do her misshapen bones and shackled ankles show us about Texas afterlives? Now, upon the discovery of her abused and abandoned body, what can we understand? The years between 1878 and 1911, when the bodies were buried, were formative in Texas’s convict leasing system and sugar cane production, both key in sustaining the state’s sugar wealth following the legal eradication of the plantation system. The bodies that rested in Texas dirt reveal the underbelly of this history of wealth and progress. Contorted bones evidence violence and exhaustion. Perhaps the bones of the woman or girl I imagine reveal gendered violence that occurred under the demands of “Texas Sugar King” Cunningham, notorious for making Sugar Land the Hell Hole. Dirt both hid the remains of the 95 and protected their stories.10

When I think back, I wonder if my body knew something that I had yet to understand but had already consumed. I recall the land I’ve traversed over the years—for field trips, for family visits, for work and leisure—and how my own body and its memories have been shaped by this place, from what I chose to hold in my hands to what my family told me to wash, peel, shuck, dig up, and bury. These are the sources of wonder and curiosity I sought to remember as I worked through the disruption of Sugar Land’s dirt. It was an opportunity bestowed by ancestors, mine and others, to unsettle not only linear ideas of Texas history but also the built environment as a means of erasure. This dirt is porous, but it’s also densely packed. It is a source of what scholar Tiffany Lethabo King calls a “flexible analytic . . . a mode of critique and an alternative reading practice.” Dirt is a container, a way to hold memory. The painful experience of reading this city’s dirt, the Sugar Land 95’s contorted bones, and the difficult truths I imagine for a girl or woman, offers me a framework for understanding the buried history of violence that went into making Sugar Land. Though these lives will in some ways always continue to dwell in the ground, their stories are being unearthed.11

The 2018 dig is a reminder that all the joy I locate in Texas soil—as a consumer, lover, and wanderer—required initimate engagement with Black death in the Hell Hole on the Brazos. The land developed for Texas’s eighteenth- and nineteenth-century economies reflects a violence that relegates Black bodies to the dirt, then literally builds on them, for the sake of progress and profit. This progress would overwrite enslavement and its afterlives altogether. There are numerous unmarked graves, burials, and bodies gone to dust and countless histories interred in the land. The Sugar Land 95 remind us that those gone to dust still reside in the dirt—and that the flesh that becomes dirt is not only a memory embedded in the land but also an archive providing access to that memory. Dirt offers Black Texas a tangible afterlife. It is intelligible only to those whose flesh is familiar with it, who feel it in their bodies, who have consumed it or are deeply connected to it. Dirt preserves Black Texas life, even in its density.

Dirt offers Black Texas a tangible afterlife.

Scholar L. H. Stallings writes that dirt is a “tool, ingredient, or craft material . . . a conductor of sacred energy.” I surmise that Texas dirt reveals difficult truths, one of which is Texas’s legacy of carcerality. Dirt offers an alternative epistemology—one that outlives the region’s many structures perpetuating violence and historical erasures. Dirt also negates material archives (documents, photos, infrastructural memorialization of the Alamo, plaques along the Brazos, and statewide social science curricula that often erase Indigenous and Black Texas life) as the sole means to advance knowledge of Texas and its origins. Wear it down, dirt seems to say. In time, dirt reveals what it holds. This alternative epistemology asks us to start with the bare soil. Its memories, dense flesh, what it knows and how it can heal, demand that we engage in the messy practice of unearthing. My encounters with Texas dirt allow me to remember differently. In this archive, Black Texan folks—who continue to communicate even in death—are whole enough to be properly remembered as humans who had feelings, wanted to love and be loved, desired freedom, and grew abundant community alongside sugar. Sugar Land has long presented a façade, but it has always been the Hell Hole on the Brazos for the 95. The sugar economy—its mills, factories, the neighborhoods and tours that it made possible—was a multilayered concrete cover built over histories of sugar, violence, and Black labor.12

The ground, in and of itself, has too often been excluded from discussions of southern enslavement, despite emerging work on Black ecologies and geographies. But, here, dirt serves as a text that allows us to chronicle Black life under settler colonialism. When we eat dirt, we practice unearthing alternative archives—of memories, past lives, legacies, and afterlives. We also resist more destructive forms of consumption. There are many Black afterlives that have yet to be unearthed.13

Today, what was once an unknown mass grave is now the Bullhead Camp Cemetery. The Sugar Land 95 have been given proper burials with individual caskets, a public ceremony, and newly dedicated tour grounds for public visits—all with the city’s promise that this dirt will serve as a reminder and a lesson for the community. And I sense that Texas dirt still has more to tell.

Endia L. Hayes is a doctoral student in sociology at Rutgers University, New Brunswick. Her work engages methods of alternative archiving among Afro-Texans by tracing sensorial, sonic, affective, and immaterial embodiments as a map of early twentieth-century Texas. She is also a contributor to Environmental History Now (EHN).NOTES

- Merriam-Webster, s.v. “eat (v.),” accessed April 10, 2021, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/eat.

- Eugene C. Barker, “Stephen Fuller Austin,” Texas State Cemetery, accessed April 10, 2021, https://cemetery.tspb.texas.gov/pub/user_form.asp?pers_id=3; “Sugar Land: Historical Timeline,” City of Sugar Land, accessed April 10, 2021, http://www.sugarlandtx.gov/1773/Sugar-Land-Historical-Timeline; Michael Hardy, “Blood and Sugar,” Texas Monthly, January 2017, https://www.texasmonthly.com/articles/sugar-land-slave-convict-labor-history/. See also Andrea R. Roberts, “Haunting as Agency: A Critical Cultural Landscape Approach to Making Black Labor Visible in Sugar Land, Texas,” ACME 19, no. 1 (2020): 210–244.

- Hanna Kim, “Unearthing Truth: The Future of Sugar Land, Texas Depends on Its Bitter Past,” DES 3333: Culture, Conservation and Design, 2018, https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/SAVINGPLACES/UploadedImages/23769d2e-1cf3-4995-b107-58280aeb6b76/Sugar_Land/Final_Paper_by_Hanna_Kim.pdf. For a discussion of Sugar Land’s Indigenous roots, see “Sugar Land: Historical Timeline”; Carol Lipscomb, “Karankawa Indians,” Texas State Historical Association, accessed April 14, 2021, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/karankawa-indians; and Jeffrey D. Carlisle,”Tonkawa Indians,” Texas State Historical Association, accessed April 14, 2021, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/tonkawa-indians.

- “Sugar Land”; Convict Leasing and Labor Project, accessed April 14, 2021, https://www.cllptx.org.

- For more on the erasure of enslavement in Texas education, please see Manny Fernandez and Christine Hauser, “Texas Mother Teaches Textbook Company a Lesson on Accuracy,” New York Times, October 5, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/06/us/publisher-promises-revisions-after-textbook-refers-to-african-slaves-as-workers.html; Michael Brick, “Texas School Board Set to Vote Textbook Revisions,” New York Times, May 20, 2010, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/21/education/21textbooks.html; and Kritika Agarwal, “Texas Revises History Education, Again: How a ‘Good Faith’ Process Became Political,” Perspectives on History, January 11, 2019, https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/january-2019/texas-revises-history-education-again-how-a-good-faith-process-became-political.

- Hardy, “Blood and Sugar”; Meagan Flynn, “Bodies Believed to Be Those of 95 Black Forced-Labor Prisoners from Jim Crow Era Unearthed in Sugar Land after One Man’s Quest,” Washington Post, July 18, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2018/07/18/bodies-of-95-blackforced-labor-prisoners-from-jim-crow-era-unearthed-in-sugar-land-after-one-mans-quest/; Matthew Clarke, “Texas Convict-Leasing Burial Ground Uncovered,” Prison Legal News, January 8, 2020, https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2020/jan/8/texas-convict-leasing-burial-ground-uncovered/.

- Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2006), 127. Grappling to mediate my personal life in Sugar Land and the brutality that marked the uncovered bodies of the incarcerated and enslaved allowed me to think alongside scholars who speak to Texas’s haunting; see Roberts, “Haunting as Agency.”

- McKittrick, Demonic Grounds, ix.

- Avery F. Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 8.

- Flynn, “Bodies Believed.”

- Tiffany Lethabo King, “The Labor of (Re)reading Plantation Landscapes Fungible(ly),” Antipode 48, no. 4 (March 2016): 1023.

- L. H. Stallings, A Dirty South Manifesto: Sexual Resistance and Imagination in the New South (Oakland: University of California Press, 2020), 38–39.

- Recent scholarship on Black ecologies and Black geographies engages the metaphorical and symbolic role of the southern soil. Some of this work around the relationship between Black life, enslavement, and settler colonialism includes Kathryn Yusoff, A Billion Black Anthropecenes or None (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018); Clyde Woods, Development Arrested: The Blues and Plantation Power in the Mississippi Delta, 2nd. ed. (New York: Verso, 2017); Katherine McKittrick and Clyde Woods, Black Geographies and the Politics of Place (Cambridge, MA: South End, 2007); Andrea Roberts and M. J. Biazar, “Black Placemaking in Texas: Sonic and Social Histories of Newton and Jasper County Freedom Colonies,” Current Research in Digital History, no. 2 (2019); “Introducing a New Series on Black Ecologies,” Black Perspectives (blog), African American Intellectual History Society, June 16, 2020, https://www.aaihs.org/introducing-the-black-ecologies-series/; J. T. Roane, “Plotting the Black Commons,” Souls 20, no. 3 (2018): 239–266; and Fred Moten and Saidiya Hartman, “Fred Moten & Saidiya Hartman at Duke University | The Black Outdoors,” Duke Franklin Humanities Institute, October 5, 2016, YouTube video, 2:04:02, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t_tUZ6dybrc. These works only begin to scratch the surface of emerging studies of Black relations to ground, particularly in the legacy of settler colonialism and the plantation.