We shall endure / To steal your senses / In that lonely twilight / Of your winter’s grief. —Pauli Murray, “To the Oppressors,” 1939

Written one year after being denied admission to graduate school at UNC, Pauli Murray mourned the defeat dealt in her desegregation efforts by the Jim Crow–era campus oppressors. She grieved the “what ifs” of an inclusive Chapel Hill campus community but expressed a fortitude necessary for perseverance. Seventeen years later, she witnessed from afar the legal victory achieved by Ralph Frasier, LeRoy Frasier, and John Brandon in overturning the campus policy that prohibited the admission of African American students on September 16, 1955. She would have cheered on those African American students who later donned their regalia at graduation and earned the degree that she originally sought. In 2005, twenty years after her death, I attempted to fill Murray’s proud shoes as I embarked on my doctoral training in the history department.2

Racism and the long campus history of race shaped my own tenure. Yet, I endured. I trained under other African American women and white faculty allies who understood Murray’s legacy. I held my head up high whenever entering Hamilton Hall and defied the lingering specter of its white supremacist namesake. I rebuffed the assaults lobbed by Silent Sam as I completed my coursework. While researching for my dissertation, I scoured the UNC libraries, where I encountered Murray’s Reconstruction-era ancestor and other African Americans who contributed to America’s second founding and then witnessed the national betrayal at the turn of the twentieth century. These founding mothers and fathers developed communities and educational institutions that nurtured Murray and paved the way for me. The resulting dissertation amplified the voices of urban African Americans who created and sustained a system of public schools immediately following the Civil War and made African American education into a lasting Reconstruction legacy. And in a Hamilton Hall seminar room on a Friday evening in April 2010, I successfully defended my dissertation and earned the degree coveted by Murray.3

I quickly embarked on a career in academia that would have made her proud. In my capacity at Elizabeth City State University and then the University of Alabama, I taught Julian S. Carr’s 1913 Silent Sam dedication speech, where he boasted of whipping “a negro wench until her skirt hung in shreds,” alongside Shelby Eden Dawkins-Law’s 2015 poem contemplating “What to the Negro Wench is University Day?” I also introduced my students to Murray, her UNC rejection, and subsequent activism for social justice as a queer Black woman. They came to understand her “subtle strength,” described in the 1939 poem. They also learned how she and others rejected the continued legacy of the white supremacist logics at the segregated school, imagined a different future, and worked tirelessly to remake a just, diverse, and inclusive campus landscape and culture. In the process, we discussed the ongoing effects of institutional complicity from not reckoning with its racist past that oppressed Murray, me, and other students of color, past and present.4

Thus, the department chairs’ announcement of renaming Hamilton Hall after Pauli Murray struck me as a fitting tribute. J. G. de Roulhac Hamilton built the archival machinery that contributed to what W. E. B. Du Bois and Carter G. Woodson called the propaganda of American history. This archival impulse actively encouraged the silencing of African American historical contributions and sustained white supremacist policies, whitewashed narratives, and inequity at the campus, region, and nation. During my tenure and beyond, scholars, alumni, and those in training sought to dismantle these racist rationales that had denied one potential Tar Heel graduate student. The groundswell of activism ultimately brought down Saunders Hall, Silent Sam, and the 2015 moratorium on building names. These department chairs, some of whom I encountered as a doctoral student, heard Murray’s poetic pleas for a more inclusive campus community. By claiming Murray for their building name, they have atoned for UNC’s rejection of Murray’s admission and moved the racial reconciliation process forward. I, therefore, proudly await seeing her name firmly enshrined in pale yellow brick and stone. Pauli Murray shall endure, indeed.5

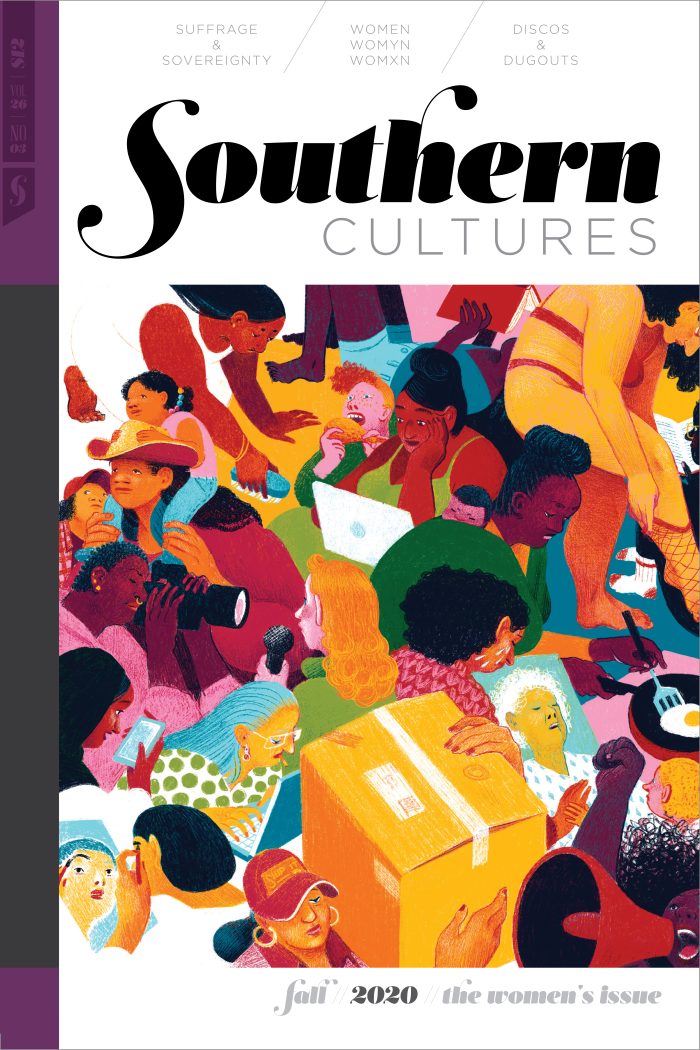

This essay first appeared in the Women’s Issue (vol. 26, no. 3: Summer 2020).

Hilary N. Green is associate professor of history in the Department of Gender and Race Studies at the University of Alabama. For the 2020–2021 academic year, she is the Vann Professor of Ethics in Society at Davidson College. She earned her PhD in history from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She is the author of Educational Reconstruction: African American Schools in the Urban South, 1865–1890 (Fordham University Press, 2016) and the creator of the Hallowed Grounds Project (2015 to present).

Header image: Hamilton Hall, UNC, ca. 1970. Courtesy of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Image Collection, Wilson Library, UNC.NOTES

- Pauli Murray, “To the Oppressors,” 1939, Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/147918/to-the-oppressors-5b9abf248443b, accessed July 31, 2020.

- Rosalind Rosenberg, Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 65–77, 385–388; William William A. Link, “Frank Porter Graham, Racial Gradualism, and the Dilemmas of Southern Liberalism,” Journal of Southern History 86, no. 1 (February 2020): 11–14; Art Chansky, Game Changers: Dean Smith, Charlie Scott and the Era That Transformed a Southern College Town (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 27.

- Pauli Murray, Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family (1956; Boston: Beacon Press, 1999), 1–23.

- Julian S. Carr, “Unveiling of Confederate Monument at University. June 2, 1913,” Julian Shakespeare Carr Papers #141, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Shelby Eden Dawkins-Law, “Letter: A Poem Questioning University Day,” Daily Tar Heel, October 12, 2015, https://www.dailytarheel.com/article/2015/10/letter-a-poem-questioning-university-day; Murray, “To the Oppressors.”

- “Pauli Murray Hall: UNC’s Departments of History, Political Science, and Sociology and the Curriculum on Peace, War, and Defense Begin the Renaming of Hamilton Hall,” June 9, 2020, https://history.unc.edu/2020/07/pauli-murray-hall-uncs-departments-of-history-political-science-and-sociology-and-the-curriculum-on-peace-war-and-defense-begin-the-renaming-of-hamilton-hall/; W. E. B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America, 1860–1880, with an introduction by David Levering Lewis (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1935; New York: Free Press, 1998), 711–729; Jeffrey Aaron Snyder, Making Black History: The Color Line, Culture, and Race in the Age of Jim Crow (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018), 35–36; Jane Stancill, “UNC-Chapel Hill Trustees to Rename Saunders Hall ‘Carolina Hall,’” News and Observer, May 28, 2015; Jesse James Deconto and Alan Blinder, “‘Silent Sam’ Confederate Statue Is Toppled at University of North Carolina,” New York Times, August 21, 2018; University Communications, “UNC-Chapel Hill Board of Trustees Lifts Renaming Moratorium,” June 17, 2020, https://www.unc.edu/posts/2020/06/17/unc-trustees-lift-moratorium/.