“It is about the aesthetic of Bourbon drinking in general and in particular of knocking it back neat . . . The joy of Bourbon drinking is not the pharmacological effect of C2H5OH on the cortex but rather the instant of the whiskey being knocked back and the little explosion of Kentucky U.S.A. sunshine in the cavity of the nasopharynx and the hot bosky bite of Tennessee summertime.” —Walker Percy, “Bourbon”1

In a 1975 essay bluntly and beautifully titled “Bourbon,” Walker Percy asserts that “The pleasure of knocking back Bourbon lies in the plane of the aesthetic but at an opposite pole from connoisseurship.” For Percy, it is Bourbon’s aesthetic condition rather than its chemical composition that makes the drink so distinctly appealing. “Knocking it back neat” serves a transportive function, immersing the Bourbon drinker in the rich cultural imagery of the American South: woody, sunny, and romantic. The hot bite of the Bourbon sensuously connects the body of the drinker to nation, region, and locale, enjoining his experience with those of imagined, historical bodies, soaking up space and place in the slow burn of what appears an endless southern summertime. For Percy, a southern doctor, author, philosopher, and social critic, Bourbon drinking serves as an existential, even religious, act which connects the drinker to an imagined history, an act which ultimately provides an “evocation of time and memory and of the recovery of self and the past from the fogged-in disoriented Western world.”2

Like Percy, I am a drinker of Bourbon. Although I (and no doubt Percy as well) appreciate both its chemical and symbolic capacities, I am primarily concerned with the symbolic, its aesthetic relation to issues of personal and cultural identity. Percy’s personal history with Bourbon began as a child in the Prohibition Twenties in his family’s Birmingham basement, as he watched his father age his own product in a charcoal barrel. The personal narrative he recounts in his essay binds Bourbon consumption to episodes of heterosexuality, homosociality, and unc football games. My personal history with Bourbon begins much later, in the suburban 2000s, at the parties of Virginia Beach schoolmates whose parents were out of town.

At this point, my interests in men like Evan Williams, Jim Beam, and Kentucky Gentleman were primarily physical, corporeal, chemical. I privileged their bodily, pharmacological capabilities over their symbolic and welcomed their presence in my stilted, surreptitious social life with the same wide arms, open mouth, and ready chaser as any gin, vodka, or crème de menthe that we could prize from our parents’ liquor cabinets. I trace the first stirrings of my symbolic appreciation of Bourbon to my second romantic relationship in college, with a white southern man who preferred it to any other liquor. During the time we spent together, I sensed something decidedly self-conscious in his choice of drink and began to conceive of it as a sort of play, a means of both challenging and asserting his place within a specific narrative of white southern masculinity, in which he was at once bound by his North Carolina lineage and excluded by his sexuality.

Back then I did not articulate his liquor choice in the same historical, theoretical terms that I do now, but I did see it as somehow ironic, an act that called into question some unspoken rules of who can drink what. In my time with this man, I began drinking Bourbon as a matter of choice and of taste, although at first I rather disliked the way it tasted. I drank Bourbon in a spirit of transgression that I could not pin down but felt that, in so doing, I took some nebulous stand against the heterosexist assumption that women and queer men drank from glasses that came with umbrellas, instead of only with ice. As I looked around me, at the fraternity parties I inevitably attended, the dorm rooms in which I inevitably found myself, and the bars into which I inevitably snuck, I realized that the self-consciousness I saw in his consumption was present in everyone’s. It dawned on me: there was something political in Bourbon-drinking.

There was something political in Bourbon-drinking.

Walker Percy and I are both southern white men of relative economic privilege, who have consumed Bourbon in the company of other men and in the same social spaces at the same southern university. Still, our respective approaches to the Bourbon aesthetic differ greatly. Percy approaches Bourbon as a straight white man, the son of a prominent Birmingham lawyer and his Birmingham wife, in many ways the prototypical southern gentleman by birth. As a queer white man from suburban Virginia Beach, the son of a working-class North Carolina father and an immigrant Irish mother, I approach Bourbon as a less prototypically southern, differently gentle man. Despite our differences, or perhaps because of them, we are both drawn to Bourbon as the symbol of a distinct southern aesthetic.3

Bourbon’s relationship to the American South is long and storied, rising literally out of the soil of the region and into its culture, both popular and private. To understand the role that Bourbon plays in the psyche of today’s white southern man, it is important to understand its history—economic, cultural, and agricultural—and its relation to the history of the South. Understanding these histories allows us to see how Bourbon drinking can serve as a bridge into the past, allowing a drinker to tap into centuries of culture with a simple consumptive act. Finally, once we understand the ways that Bourbon drinking ties consumers directly to histories of race, gender, class, and sexuality, we can see how distinct individuals—Percy, me, or any other—can function within the Bourbon aesthetic. Consequently, we can begin to understand Bourbon’s potential to maintain, negotiate, and challenge existing power relations in the contemporary southern social landscape, one drink at a time.

Drinking Our Way to the Past

In popular imagination, the southerner has long been seen as a social creature, one that lives to eat, drink, visit, and tell stories. Indeed, southern historian W. Fitzhugh Brundage observes that “Southerners, after all, have the reputation of being among the most historically oriented of peoples and of possessing the longest, most tenacious memories.” The methods and mechanisms through which individuals and groups carry out their remembering are diverse, encompassing shared stories and oral histories; public monuments and memorials; cultural rituals and artistic practices; and of course eating and drinking traditions, among others. By these varied recollective practices, groups and individuals pay homage to the past while establishing their identities in the present, as shaped by the history— either real or imagined—to which their remembrances refer. Although the analysis of any group’s eating patterns, or foodways, can be quite valuable in understanding its culture, the American South is especially suited for a study of consumption. As southern foodways scholars such as Marcie Cohen Ferris and John Egerton have shown, politics, poverty, and oppression have shaped the culinary traditions of the South, so these traditions are distinctly imbued with great cultural weight. In the continuously changing, constantly globalizing contemporary South, foodways have survived as largely intact markers of historical southern identity, even as many of the concrete sociopolitical institutions of the Old South have faded into, well, history.4

In today’s South, where it seems young men can travel to Bangkok about as readily as Baltimore, Bourbon remains a piece of masculine identity that southerners can “put on,” much like overalls, a seersucker suit, or a North Carolina twang. Bourbon adds an even deeper dimension to the “putting on” of identity because it is literally taken into the body of the drinker, affecting him in both image and consciousness. As the epigraph illustrates, a drinker feels the Bourbon’s “bite,” which connects him sensuously via literal consumption, as well as aesthetically via symbolic consumption, to a narrative of imagined rurality, of nostalgia for a South that is no more, and can only be recalled with a few straight shots of Kentucky straight Bourbon whiskey. In putting back a few shots of the stuff, we “perform” identities, identities tied to race, class, gender, sexuality, and, ultimately, history. Such performances of identity give us insight into the ways people not only present themselves, but also perceive of themselves, know themselves, and know of others. By studying these performances in a given cultural context, we can begin to see which identities are privileged and which are policed in that culture. To understand Bourbon’s function today, it is thus crucial to understand its history, as bound to the agriculture, economy, and settlement of the American South.5

Bourbon remains a piece of masculine identity that southerners can ‘put on,’ much like overalls, a seersucker suit, or a North Carolina twang.

The story of Bourbon’s ascent from the ripe ground of the southern colonies into the collective consciousness of today’s South is a story of thirst, industriousness, and, perhaps above all, corn. Today’s Bourbons follow strict legal codes of composition, bubbling forth with terms both scientifically severe: “produced at not exceeding 160º proof” and charmingly quaint: “in charred new oak containers.” Bourbon’s early ancestors, however, were born of the efforts of the earliest American settlers and were closer kin to today’s moonshine than to anything we might recognize as Bourbon. By the late 1790s, a significant population of Scots-Irish had settled in Maryland and Southwest Pennsylvania and had “brought with them the strongly held opinion that whiskey, not bread, was the staff of life, the equipment for distilling, and an expert knowledge of the distiller’s art.” These settlers quickly took to squeezing liquor out of the land, using primarily local rye, but also grains, fruits, and even vegetables, distilling just about anything that could be made to ferment. As these settlers moved South through Appalachia to Kentucky across the Cumberland Gap, they discovered southern corn, the region’s supercrop.6

While rye grew well in Pennsylvania and Maryland, corn grew like wildfire in Kentucky. Settlers could plant it quickly, even haphazardly, and its yield was robust and bountiful. Kentucky farmers ate their corn, drank their corn, and fed it to their animals. They also quickly learned that the fastest way to turn their excess harvest into extra cash was to distill it, as liquid travelled better than grain across the mountains that hedged in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region. The road to Bourbon’s prominence in the mind of the South was thus paved with corn, like much of the region’s cuisine and resultant culture. Distillation slowly evolved from a by-product of the harvest to its principal purpose, and the rotgut corn whiskey of yore slowly evolved into the smooth stuff we know today as Bourbon.7

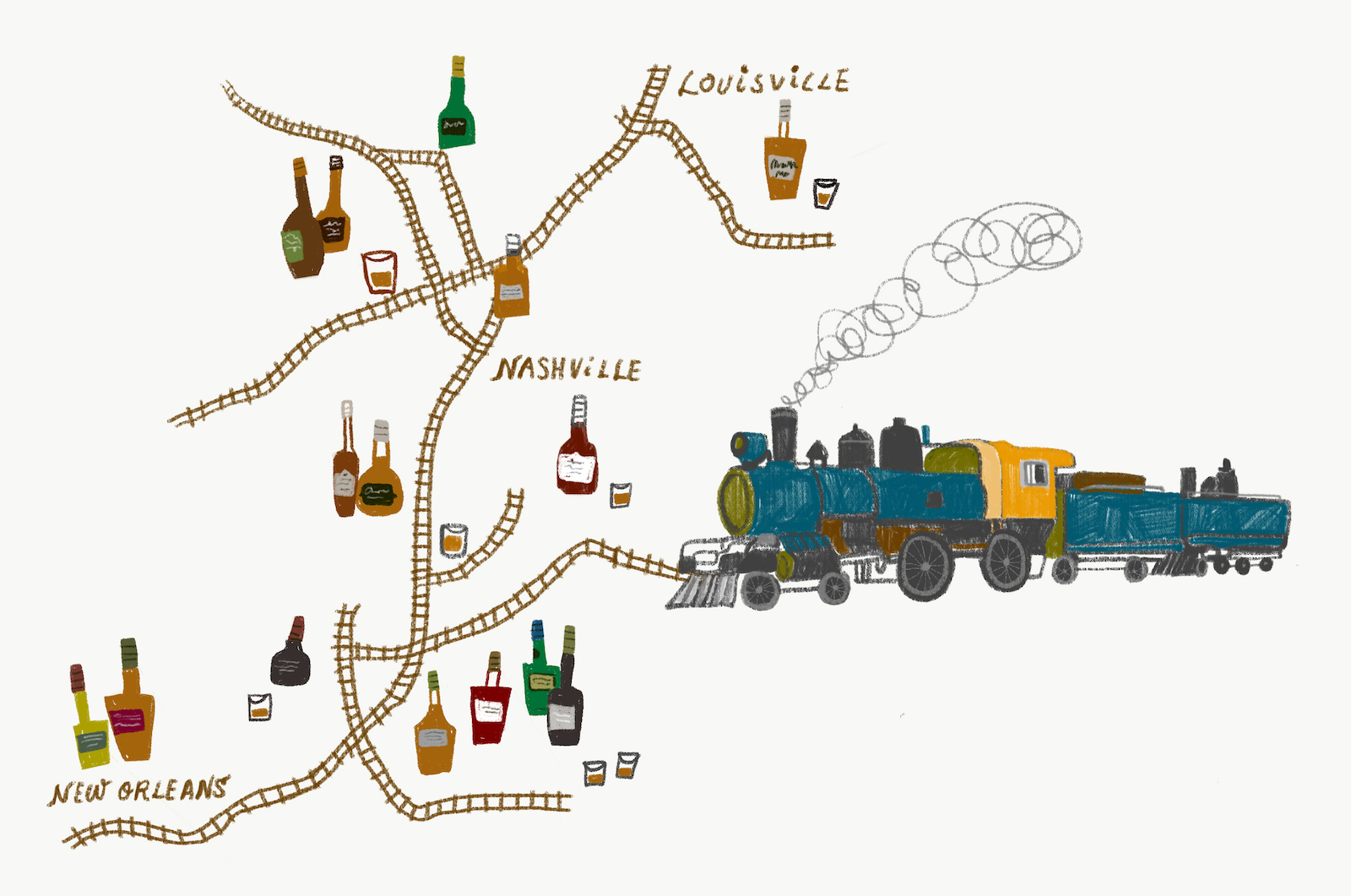

Accounts of this evolution differ greatly. The most cherished story of Bourbon’s conception has it that Elijah Craig, a late-eighteenth-century Baptist minister and the namesake of a small-batch Bourbon today, distilled the first true Bourbon. Legend has it that Craig—perhaps a result of divine providence—decided to age the whiskey that others were drinking green and named it based on its place of origin, Bourbon County. Historians have disproven the story on many counts, chief among them that Craig never distilled whiskey in Bourbon County. More accurately, it was the increasing standardization and commercialization of the Bourbon industry that led to Bourbon’s routine aging in charred oak barrels, and to the appealing mellowness and attractive ruddiness it takes on after a few years in the barrel. As efficiency in distillation rose, and with it Bourbon surpluses, distillers increasingly shipped their product throughout the South, down the Ohio River en route to New Orleans and along the Louisville and Nashville Railroad to the rest of the southern colonies. Like grits and cornbread, corn whiskey began to settle into the collective consciousness and consumption patterns of the South.8

Unlike grits and cornbread, however, Bourbon is of particular importance in the study of white southern masculinity because of its distinctly constructed white southern maleness. Generally speaking, much of a culture’s food production has historically been the province of its women, and has taken place within the home. Alcohol, however, is an important exception, as its production and consumption have, in many cultures, remained the jurisdiction of men. This was especially true in the gendered Old South, where plantation gentlemen used whiskey to construct a homosocial environment apart from women and children, and common southern men used it to liven any meal or social gathering. Bourbon, more than other staples in the southern culinary tradition, thus offers a singular insight into white southern masculinity. Bourbon is also the only indigenous, distinctly southern liquor, recognized by Congress in 1964 as “America’s native whiskey.”9

Noting the southern predilection for the drink, Bourbon historian Charles Cowdery goes so far as to refer to the region as the “bourbon belt.” Bourbon thus exemplifies southern drink, and since southern drinking has long served in the performance of southern manhood, Bourbon has been distinctly imbued with the rich historical narrative of the white southern male. Examined in relation to its representation in popular culture, we learn how Bourbon drinking plays a crucial role in the everyday performance of white southern masculine identities.10

Every Ounce a Man’s Whiskey

Over the last few centuries, corn whiskey has thus evolved from rotgut into Bourbon, and from Bourbon into today’s Bourbon market glut. What was, as late as the 1960s, a humble market of spirits left almost exclusively on the bottom shelf has become an endlessly niched carnival, with distilling houses now producing Bourbons premixed with cola or honey, aged any number of years, and increasingly designated as “ultra-premium,” small-batch, or single barrel. As the market has become more diverse, so have the branded identities that distillers use to drive their sales and shape their target market. Maker’s Mark and Early Times emerge as two points on a spectrum, brands that project two distinct, though related, consumer identities: the gentleman and the good old boy. Although multiple factors have shaped cultural images of Bourbon, from film to literature, art to advertising, the latter provides particular insights because of the strategic nature of its image construction, tied both to economic gain and cultural appeal. Brands work to maintain distinctive identities, while keeping their representations flexible and inviting enough to allow for the participation of individuals who do not wholly, or even significantly, resemble the ideal consumer. This tension allows for analysis of the ways that real and diverse people interact with Bourbon’s historical legacy, as they consume a company’s branded identity along with its liquor.11

In a region long obsessed by history, it only seems fitting that contemporary performances of masculinity would borrow heavily from their ancestral archetypes. In the case of the southern white man, two more or less historically consistent tropes emerge: the gentleman, with his roots in the moonlight-and-magnolia planter ideal, and the good old boy, his backcountry cousin. It is important to view these social types not as accurate depictions of the way white men are in the South, but instead as archetypal wells from which today’s men draw as they craft and express their identities. Individuals move between, into, and around these types as they adjust their drawl, change their clothes, and switch from Early Times in a pickup to Maker’s on the rocks. Even in the Old South, the distinctions between the gentleman planter and the yeoman good old boy were often more imagined than real. According to the infamously quick-quilled southern social critic W. J. Cash, the gentlemen of yore were really nothing more than the most successful of the backcountry pioneers, the former good old boys. As they gained land and property, they rapidly reinvented themselves as southern nobility, adopting the imagined customs and habits of the existing European aristocracy.12

Bourbon in the 1960s was the drink of the working class. In the Old South, where corn whiskey was the only liquor available, the age and character of the whiskey served to convey class and status. By the 1960s, however, the increasing availability of and American preference for exotic European imports led well-heeled southerners to reach for Scotch or Cognac, in much the same vein of affected Europeanism as the earlier colonial gentlemen. Maker’s Mark president Bill Samuels Sr. introduced his product as Cognac’s counterpart among Bourbons with an audacious advertising campaign in 1965, closing the gap in the market and retying American whiskey to the patrician planter mythos. Reading the self-consciously classed claims of a 1972 Maker’s Mark ad in conversation with those of a 1953 Early Times ad shows the continuity of Bourbon’s masculine messaging up to today.13

Two burly men, up with the early morning sun, load bait, tackle, and apparently a bottle of Early Times for a day of fishing, a tradition of deep historical importance to the southern man. The nature of the fishing these two men are about to do, as well as the nature of the image itself, evoke a romantic view of the working man’s recreation, which meshes well with Early Times, the working man’s drink. They have strong forearms, day-old beards, and are covered in flannel. Like any self-respecting good old boy, these men are dressed not to impress, but instead to fish and drink the day away. By staging the scene on Kentucky’s “man-made lake,” the ad bestows another dimension of virility on its clientele, unfazed by a lack of lake when he wants to fish. Not to worry, the Early Times good old boy will build his own lake! The southern man, potent and strong, has dominion over nature and will subdue the world around him for the good time he wants and deserves.1

The folks at Early Times go yet a step further in spelling out their message. With apparently little faith in their audience’s knack for subtlety, the primary text in this ad tells us in very direct terms that Early Times “is Kentucky’s favorite Bourbon because it’s every ounce a man’s whisky.” Not only is Early Times Kentucky’s favorite Bourbon and every ounce a man’s whisky, Kentucky actually prefers Early Times because of its manliness. Not only do good old boys from the South love their Early Times, the South loves its good old boys right back!15

With its entry into the Bourbon market in the late 1950s, Maker’s Mark stands in for the contemporary gentleman, looking down on the Early Times good old boy with self-conscious awareness of the lineage they share. When the product was introduced in 1958, it was priced at almost double the going rate for Bourbons, and with little justification, “especially since it didn’t claim any extra age (it didn’t claim any age) or any other tangible attribute to justify its price.” The product claim is almost absurdly explicit in its transparency: the reason one should drink Maker’s is precisely because it is expensive, because it appears refined. Restated, the ad reads: drink Maker’s Mark because it makes you look rich. As opposed to the Early Times ad, with its idyllic and explicit portrayal of working-class southern manhood, the Maker’s ad works to impart its southern masculinity only secondarily to its assertion of class. Above all else, this ad asserts that Maker’s Mark is expensive, with the bold declaration that dominates the text. The gentlemanliness of the product does read, however, in the classic simplicity of design and in the message of the smaller block of text. The spirituous secret, we are told, is in the “original old style sour mash recipe” that runs back through four generations of patrilineal know-how. Evoking nostalgia for the agrarian idyll of a bygone South, the address at the ad’s bottom—”Star Hill Farm, Loretto, Kentucky”— furthers this ethos of southern stateliness. Although possible, it seems unlikely that Samuels included the address to solicit post from consumers. More likely, it serves to conjure in the mind of the drinker a nostalgic image of the “Moonlight and Magnolias” South, on a farm (or a plantation) in rural Kentucky, where he might be taken in, sat down, and invited to sip a Julep while the sun sets and time stands still.16

A quick look at the websites of each brand shows that the distinct images of drinker circulated by each have remained more or less consistent over the years. The homepage for Early Times appears as a sort of good old boy playroom, filled with totems of blue collar leisure: an “Early Times” neon sign, a bar with obligatory Early Times bottle, a mounted bass, a tool kit, and a framed poster of a horserace, among other trophies of manliness. To the delight of the viewer, a quick rollover animates the relics; they come to life as if shot in a booze-laden carnival shooting gallery. The aesthetic is rowdy, country, and fun, and the hunting, fishing, and neon motif reads loud and clear. From its earliest years to today, Early Times has exuded unrestrained, unrefined white southern manhood.17

If the Early Times website is a shooting gallery shrine to working class southern whiteness, the Maker’s Mark website is a vault of gentlemanly heritage: the primary graphic on the page is a magnified image of the brand’s iconic bottle, cropped to show only a portion of the neck. As the light plays lambent on the contours of the bottle, illuminating the Bourbon inside, the image evokes antiquity, appearing as fossilized amber. The two tendrils of red wax that drip down the neck appear strangely poignant, eerily resembling the genteel blood that runs through the neck of each Maker’s Mark consumer. The differences between these homepages extend to the rest of the sites, with Maker’s Mark privileging information, heritage, and gentility, and Early Times privileging fun, machismo, and irreverence. The tool kit totem on the Early Times website links to a “Tools” page, where the good old boy finds articles with everything to do with tools and nothing to do with Bourbon, save the rugged manliness they share. In contrast, we find the “Tasting notes” section on the Maker’s Mark site, which reads as delicate verse. The page assesses the color, bouquet, flavor, and finish of the Bourbon, stating that ideally, the bouquet would present as “Full, yet delicate; well-rounded; possessing a distinctive caramel aroma of the charred oak with a hint of vanilla; pleasant and inviting.” One can imagine the archetypical good old boy stumbling across this online and wondering out loud why there are flowers in the whiskey.18

The irony of Maker’s Mark as a bastion of white southern male heritage lies in its relatively recent arrival into both the market and the mind of the consumer, especially in relation to Early Times, which traces its origins to 1860, about a century before Maker’s hatched under Bill Samuels Sr. When the Early Times advertisement circulated in 1953, it was not explicitly targeting good old boys per se, as good old boys were the only boys drinking Bourbon at all. With Samuels’s introduction of Maker’s Mark in the late 1950s, he worked to craft a timeless image of the brand that effectively introduced, or reintroduced, the idea that gentlemen drank Bourbon. It was Maker’s Mark’s entry into the industry as the gentleman’s choice that eventually forced Early Times to acknowledge and articulate its good-old-boydom as such. In this light, contemporary masculine performances of “gentleman” and “good old boy” appear like the Old South planter and his yeoman kin, bound inextricably and self-consciously, with each defining itself largely in relation to the other. The marketed myth of the Bourbon-sipping gentleman cemented the image of the Bourbon-swilling good old boy.19

The market-driven manhood evident in these investigations goes to show the constructedness of any identity, but particularly that of the white southern man. To effectively approach Bourbon’s function in the contemporary American South, however, it is critical to do so within a theoretical framework that lets us understand the methods by which masculine power exerts and sustains itself. R. W. Connell, in his seminal book Masculinities, articulates just such a framework, the notion of “hegemonic masculinity.” Connell posits that there is no such thing as an objective masculinity, universal and innate, observable in men as a whole. Instead, masculinities are constructed through relations of gender, sexuality, race, and class and are located in specific intersections of place, time, and culture. Although there is no singular masculinity to which all men subscribe, particular “hegemonic masculinities” will emerge within a particular social environment, exerting various forms of power over subordinate and marginalized expressions of gender, in the ultimate aim of sustaining patriarchy. Although I do not seek to chart a comprehensive cultural analysis of the white southern man, I do assert that in today’s South the gentleman and good old boy, or their performed approximations, are exalted. Although the masculinities projected by Maker’s Mark and Early Times vary in their articulations of class, they share a preoccupation with whiteness, history, and homosociality, and an implicit antagonism toward women, people of color, and homosexuality, antagonisms echoed throughout the lingering southern social order.20

That anyone can drink Bourbon calls into question the notion, articulated outright by Early Times, that it is every ounce a man’s whisky. Is it?

Of course, Bourbon alone is in no way responsible for contouring the landscape of today’s South, but it is one of many vital and tangible tools in this landscape’s maintenance—and, hopefully, its alteration. Each brand has invested significant effort in shaping its identity, but none is so narrow in its articulation that it explicitly discourages consumption by any who are willing to buy bottles. This reality leads to slippages and fissures between the layers of race, class, gender, geography, and sexuality built into these branded identities and leads ultimately to points of entry for those not privileged by these identity markers. True, the gentleman and the good old boy persist as ideals for many in the South, but even these are open to interpretation, contestation, and play. That anyone can drink Bourbon calls into question the notion, articulated outright by Early Times, that it is every ounce a man’s whisky. Is it?

Bourbon’s Political Turn

To set the stage for Bourbon’s political potential, I start at a seemingly unlikely place: the social phenomenon of “icing.” For those unfamiliar, icing is a ritual made briefly but wildly popular around 2010, whereby an individual (usually male, often called “Bro”) “ices” another (also often called Bro) by revealing a Smirnoff Ice lemon-flavored alcoholic beverage anywhere in the visual field of the person (Bro) being iced. Bro ices Bro. Upon said icing, the icee must lower to his knee and consume the entire beverage, to the great pleasure and cheer of all present. The practice, which allegedly got its start in and around southern social fraternities, went on to enjoy significant celebrity, a dedicated website (brosicingbros.com, now defunct), various offshoots (hoes icing bros, hoes misting hoes), and a New York Times article. Though most see this ritual as good-natured, harmless, binge-drinking fun, it does not take much creativity to understand its gendered symbolism, or its implications. A man forces another man to kneel publicly, insert an object into his mouth and consume its sweet contents, while others hoot and holler. Imitations of fellatio, intimations of fruitiness; what a fun party! The power and the play in icing come in its ridicule of (and distance from) men who perform real fellatio and exhibit real “fruitiness.” The particular resonance of Smirnoff Ice in the practice lies in the common understanding that it is a “girly” drink, in the category of those sweet malt beverages colloquially and disturbingly known as “bitch beer.” By casting gay sex and sweet beverages to the realm of the ridiculous, icing elevates heterosexuality and the consumption of unsweet beverages to the realm of the sublime.21

Besides sharing demographic practitioners, Bourbon-drinking and icing are intimately related, as both are performative, consumptive social practices that subtly but significantly shape the ways we conceive of ourselves and of others. There are, however, important differences. The performance in icing is more obvious, more spectacular; it is staged and almost always features a knowing audience. Bourbon drinking is subtler, but is also therefore more insidious, more ingrained, more pervasive; it conveys information subconsciously. Icing is also novel. Though some men (and women) are undoubtedly still icing each other somewhere, the popularity of the practice left us about as quickly as it came. Bourbon, meanwhile, perseveres, gaining cultural clout and market share. Finally, Bourbon is more sacred. It has been written indelibly into the history of the white masculine South, by Percy, Faulkner, and our fathers, through advertising and through our consumption, for centuries. That history, conversely, has been written into Bourbon, and it is that history that we perform, consciously or not, when we drink it.

Returning to Connell’s notion of hegemonic masculinity, we can see the importance of culture in considerations of power. Connell’s work draws from that of Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci, whose notion of hegemony extends traditional Marxist considerations of power into the realm of the cultural. Hegemony is an especially productive frame for a study of identity and consumption because it conceives of power as intricate and interwoven, incorporating not only political thought and economic materialism, but also mundane choices and behaviors as they relate to personal and collective identity. Culture, and specifically the culture of Bourbon-drinking, thus becomes an important site to ground explorations of power in the South.22

In a region steeped in the history of its own tumultuous past, a past that placed Bourbon-drinking (not to mention land-owning and voting) in the domain of the white southern man, Bourbon becomes a politically charged substance. As opposed to the lightness and frivolity of Smirnoff Ice, the very lightness (read: weakness, gayness, girliness) mocked and derided in icing, Bourbon is decidedly heavy, serious. The weight and gravity of Bourbon register both symbolically through the drink’s historical legacy and sensuously through its bite—that burn that makes learning to drink whiskey hard work and separates the proverbial men from the boys (and girls, and queers). When a straight white southern man sidles up to a bar for a Bourbon, he is—whether consciously or not—asserting cultural, physical, and material power. When someone of a different background does the same, this person is—whether consciously or not—challenging that very same history and their exclusion from its positions of privilege.

Thus, the painful physicality that makes Bourbon feel and appear powerful also interestingly makes Bourbon appropriable to those who have not featured in its history, and who have been marginalized by and throughout the history of the American South. Anyone of legal drinking age can sidle up to just about any bar in the South and beyond, can order a Maker’s Mark or an Early Times, can knock it back neat and brace through “the little explosion of Kentucky U.S.A. sunshine in the cavity of the nasopharynx,” and can sink into the “hot bosky bite of Tennessee summertime.” Sinking further, anyone can steep in the smoke, the soil, and the sweat of Bourbon’s imagined history, tasting its legacy and relishing its grit.

Of course, the politics of Bourbon-drinking is messy and murky. By appropriating its legacy we are by nature participating in it; by challenging southern structures of oppression we are by nature acknowledging them. A different politics might be seen in the unabashed embrace of Smirnoff Ice, the championing of the sweet, the feminine, the sugary. But by choosing to drink Bourbon and to approach its politics, queer, female, black, and other oppressed bodies can problematize accepted notions of power and privilege. By extension, these individuals trouble accepted notions of who can say, do, or think what. In staging these small, mundane performances, we change the character of the spaces we inhabit. By drinking Bourbon in protest, in play, and in pleasure, we can point to new, more complicated ways of understanding identity and living with each other. Looking around us, soaking it in, we can see the walls and contours of a region slowly shifting. In its dually sensuous and aesthetic capabilities, Bourbon-drinking becomes an act of both tasting and making history, grappling with a particular past while pointing to possible futures.

This article first appeared in Vol. 18, No. 1 (Spring 2012).

Seán S. McKeithan is a development writer & editor at New York Public Radio. He completed his graduate work in Performance Studies at the University of California, Berkeley and is a 2009 graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where research for his honor’s thesis, “Hegemony, Mythology, Bourbon: An Exploration of White Southern Masculinities,” became the impetus both for the article in this issue and On Breathing in the Barrel, a solo theater work he wrote and performed, which debuted in the 2011 Solo Takes On Two festival at UNC.NOTES

- Walker Percy, “Bourbon,” in Signposts in a Strange Land, ed. Patrick Samway (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 1991), 102–07.

- Ibid.

- John F. Desmond, “Percy, Walker,” in Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Literature, ed. Charles R. Wilson (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 383–385.

- W. Fitzhugh Brundage, “Introduction: No Deed but Memory,” Where These Memories Grow: History, Memory, and Southern Identity, ed. W. Fitzhugh Brundage (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005), 2; As scholarly considerations of the past have shifted over the last century, many critics have sought to displace the primacy of supposedly objective “historical” accounts, noting that such accounts, as objective as they may try to be, still bear the biases of their authors and have the potential to leave out perspectives and experiences of entire groups. Scholars concerned with the broad field of collective memory, in the tradition of French sociologist Maurice Halbwachs, have moved instead toward emphasis on the subjective, affective nature of shared memories, placing equal critical weight on the ways that individuals remember themselves as on the factive truths that generate their memories. Liliane Weissberg, “Introduction,” Cultural Memory and the Construction of Identity, ed. Dan Ben-Amos and Liliane Weissberg (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1999), 7–26; Carole Blair, “Communication as Collective Memory,” in Communication as . . . : Perspectives on Theory, ed. Gregory J. Shepherd, Jeffrey St. John, and Ted Striphas (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2006), 51–59; Marcie Cohen Ferris, Matzoh Ball Gumbo: Culinary Tales of the Jewish South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005); John Egerton, Southern Food: At Home, on the Road, in History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993). With the assertion that the institutions of the Old South have faded, I do not intend that today’s South is in any way utopian, freed from racism, sexism, and the oppressions that defined the Old South; far from it. Instead, even in the absence of the slavocracy, the majority rural population, and the other tangible institutions that once defined the South, they stubbornly persist.

- Charles R. Wilson, “Myth, Manners, and Memory,” Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Myth, Manners & Memory, ed. Charles R. Wilson (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 3; As folklorist Susan Kalcik asserts, the acts of eating and drinking are acts rooted in performance, specifically in symbolic performance via consumption: “since foodways operate at a symbolic level to communicate information about group membership, status, boundaries, and so on, they would be an obvious choice for symbolic manipulation by individuals and groups who wished, consciously or unconsciously, to make a statement about identity” (54). Susan Kalcik, “Ethnic and Regional Foodways in the United States: The Performance of Group Identity,” Ethnic and Regional Foodways in the United States, ed. Linda Keller Brown & Kay Mussell (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1984), 37–65.

- Charles Cowdery, “Bourbon Whiskey,” Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Foodways, ed. John T. Edge (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 128; Gerald Carson, The Social History of Bourbon, an Unhurried Account of Our Star Spangled American Drink (New York: Dodd Mead, 1963), 10.

- Carson, The Social History of Bourbon, 24–32; Mary K. Bonsteel Tachau, “The Whiskey Rebellion in Kentucky: A Forgotten Episode of Civil Disobedience,” Journal of the Early Republic 2, no. 3 (1982): 243.

- Charles Cowdery, Bourbon, Straight: The Uncut and Unfiltered Story of American Whiskey (Chicago: Made and Bottled in Kentucky, 2004), 23–56.

- Richard Harwell, “Mint Julep,” Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Foodways, ed. John T. Edge (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 198; Joe Gray Taylor, Eating, Drinking and Visiting in the Old South: An Informal History (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1982); “U.S. Senate Declares September ‘National Bourbon Heritage Month,’” Business Wire, http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20070806005376/en/U.S.-Senate-Declares-September-National-Bourbon-Heritage (accessed December 17, 2008).

- Cowdery, “Bourbon Whiskey,” 129.

- Nielsen, “A Brown Christmas? Whiskey and Brown Sprits Sales Making a Comeback, Nielsen Reports,” The Nielsen Company, December 15, 2008.

- In his Southern Folk, Plain and Fancy (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1986), John Shelton Reed seeks to map out the white southern male, adopting a complex matrix of eight social types based on race, sex, class, moral character, and strength, or efficacy. Leaving out moral character and efficacy, I arrive at two approximate types, the gentleman and the good old boy, as they allow for more flexibility, while avoiding fixed characterizations based on changing attributes of personality. I find Gail Gilchrist’s Bubbas & Beaus: From Good Old Boys to Southern Gentlemen, A Close Look at the Customs, Cuisine, and Culture of Southern Men (New York: Hyperion, 1995) to be a more useful guide, with its rollicking, semi-scholarly approach to the two types, focusing on the traditions and behavioral affectations of the two; W. J. Cash talks at length about the interrelation of the planter and the yeoman on the southern frontier in his seminal Mind of the South (New York: Vintage Books, 1941). In his characterization, even the earliest settlers used whiskey to convey notions of class, power, and privilege, with self-styled aristocratic planters occasionally lavishing good whiskey on their poor neighbors in conspicuous, condescending displays of the noblesse oblige that naturally came with the status of noblesse (42). Although distanced by these actual and performed class differences, white males in the Old South ultimately acknowledged their similarity, especially as it related to perceived elevation above slaves and American Indians (14–43).

- Cowdery, Bourbon, Straight, 162.

- Glenn Morris, “Fishing,” Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, ed. Charles R. Wilson (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989), 1219.

- At the time of the ad’s printing, Early Times was indeed a Bourbon. Today’s version is not technically a Bourbon, but it is still sold as one and considered in research as if it were. In 1983, Early Times began distilling Early Times “Kentucky Whisky,” which has only 75% of its contents aged in new oak barrels, as opposed to the 100% required by legal code. Currently, only Early Times Kentucky Whisky is sold in the United States, although the Bourbon composition is still distilled in Kentucky and sold in foreign markets. This change was likely a cost-cutting measure on the part of Early Times’ owner Brown-Forman, as they realized that Early Times was seen in the market as a value brand, purchased by customers who care more about the potency and masculine representation of their whisky than its composition. This insight into Early Times’ inauthenticity as a true Bourbon adds an additional layer to the image of Early Times as the lesser, bastard cousin of purebred Bourbons such as Maker’s Mark. Brown-Forman, “Early Times: The Whiskey That Made Kentucky Whiskies Famous,” PowerPoint Document, Early Times Brand Meeting, February 21, 2003; Cowdery, Bourbon, Straight, 16.

- Cowdery, Bourbon, Straight, 162.

- The essay discusses the Early Times homepage as of March 16, 2009. It has since changed. http://www.earlytimes.com.

- The essay discusses the Maker’s Mark homepage as of March 16, 2009. It has since changed. http://www.makersmark.com; “Tasting Notes,” Maker’s Mark, http://www.makersmark.com/index.aspx?mid=210&pgid=85 (accessed March 16, 2009).

- Cowdery, Bourbon, Straight, 160–168.

- R. W. Connell, Masculinities (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).

- J. David Goodman, “Popular New Drinking Game Raises Question, Who’s ‘Icing’ Whom?” New York Times, June 9, 2010, B3; Annie Werner, “Bros Icing Bros: Has the Icing of Bros Affected Smirnoff Ice Sales?” Village Voice Blogs, May 28, 2010, http://blogs.villagevoice.com/runninscared/2010/05/bros_icing_bros_6.php (accessed October 8, 2011).

- Steve Jones, Antonio Gramsci: Routledge Critical Thinkers (London: Routledge, 2006).