“Robinson’s photographs capture a history that proudly exposes their liberty, individuality, fraternity, and, above all, their joy.”

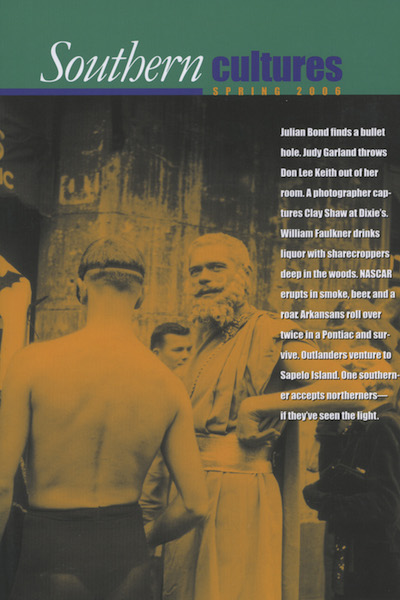

Jack Robinson’s New Orleans Mardi Gras Photographs, 1952–1955

The 1997 discovery in Memphis of thousands of images taken by a southern photographer, Jack Robinson (1928–1997), has thus far attracted only slight attention from the art world and the national press. This is, in part, because so little is known today of Robinson’s success as a fashion and celebrity photographer in the 1960s, when he took more than a hundred thousand photographs of the era’s rich, famous, and beautiful for trendsetting magazines such as Vanity Fair and Vogue. And yet the extraordinary images that are Robinson’s legacy also give us a rare and remarkable perspective into the lives and lifestyles of southern artists and bohemians in the 1950s. This small representation of his 1950s photographs, published here for the first time, is part of an overall effort to bring Robinson and his early work out of the shadows.

As a Memphian and southern historian, I took it upon myself in May 2004 to unlock the mysteries of Robinson’s life growing up in Clarksdale, Mississippi, and honing his skills as a photographer in his twenties in New Orleans. A few letters, two clippings, and a postcard were about the extent of the primary written record from the period, but hundreds of negatives from the 1950s promised to provide clues to the artist’s past.

Very little was then known about Robinson’s life in the South. He graduated from a Clarksdale high school in 1945 and attended Tulane from 1945 to 1948 but left after his junior year without graduating. He was back in New Orleans by 1951 and had started taking photographs. In 1955 Robinson left the South for New York City and the world of fashion photography. Editors Diana Vreeland and Carrie Donovan recognized Robinson’s genius and tapped him to shoot portraits of 1960s rising stars in music, art, film, fashion, and entertainment. From 1965 to 1972, Robinson’s work was published in Vogue more than five hundred times, and his portraits advanced the careers of Joni Mitchell, Clint Eastwood, Tina Turner, Warren Beatty, Lily Tomlin, The Who, Rod McKuen, and dozens more.1

On some occasions, Robinson’s personal life entered the frame. His photographs of Andy Warhol and The Factory indulging in New York City nightlife seem to include the photographer as a participant and hint at Robinson’s own homosexual identity and self-destructive lifestyle. By 1970 he was purportedly downing a fifth of vodka a day.

Jobs dwindled as the alcohol took its toll, and in 1972 Robinson left New York and moved to Memphis, where his parents and brother lived. He never worked as a serious photographer again and even hid the fact that he had been such a success. He seemed to gain control of his drinking and found work designing stained glass in a local studio, but Robinson was bitter and difficult to work with. He died in anonymity in 1997.2

After Robinson’s death, his heir, Dan Oppenheimer, in whose studio Robinson worked, discovered in the artist’s modest and austere apartment banker’s boxes filled with envelopes containing thousands of negatives and contact sheets. The names of some of the most famous people of the twentieth century were scrawled on the envelopes. There were also dozens of older envelopes from the 1950s with unfamiliar names and a few simply labeled “Mardi Gras.”

The Jack Robinson Gallery and Archive, which opened in Memphis in 2002, had its hands full preserving and promoting Robinson’s 1960s photographs of famous and beautiful people. The contents of many older envelopes had not been examined, and the gallery was more than happy to have a historian take an interest in their contents.

The visual impact of the photographs and their revelations about the community of southern artists and bohemians in New Orleans were astounding.

The visual impact of the photographs and their revelations about the community of southern artists and bohemians in New Orleans were astounding. In spite of Robinson’s creative spelling and frequent use of only first names, I identified many subjects, some of whom were, and still are, locally well-known and productive Gulf Coast artists. Other subjects were important benefactors and participants in the arts and entertainment community and local “beautiful people” in 1950s New Orleans society. From the photographs and interviews with Robinson’s friends and associates, the story of his life and the place and culture that shaped his art emerged.

Like authors Lyle Saxon, Sherwood Anderson, Roark Bradford, William Faulkner, Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, Shirley Ann Grau, Harnett Krane, and Anne Rice, Robinson found his early inspiration in the life and characters of the French Quarter. Preservation efforts had lagged in the 1950s, but the Vieux Carré continued to attract artists, writers, actors, and entertainers, many of whom were war veterans, with its twin advantages of low rent and vital bohemian culture.

The polite, soft-spoken homosexual artist from Mississippi found the Quarter to be the perfect place to spend his early twenties. Robinson quickly got a job as a graphic artist in an ad agency. His friends and colleagues, mostly artists and designers, recognized his talent and assisted his development in the playful spirit that characterized the local arts community after World War II.

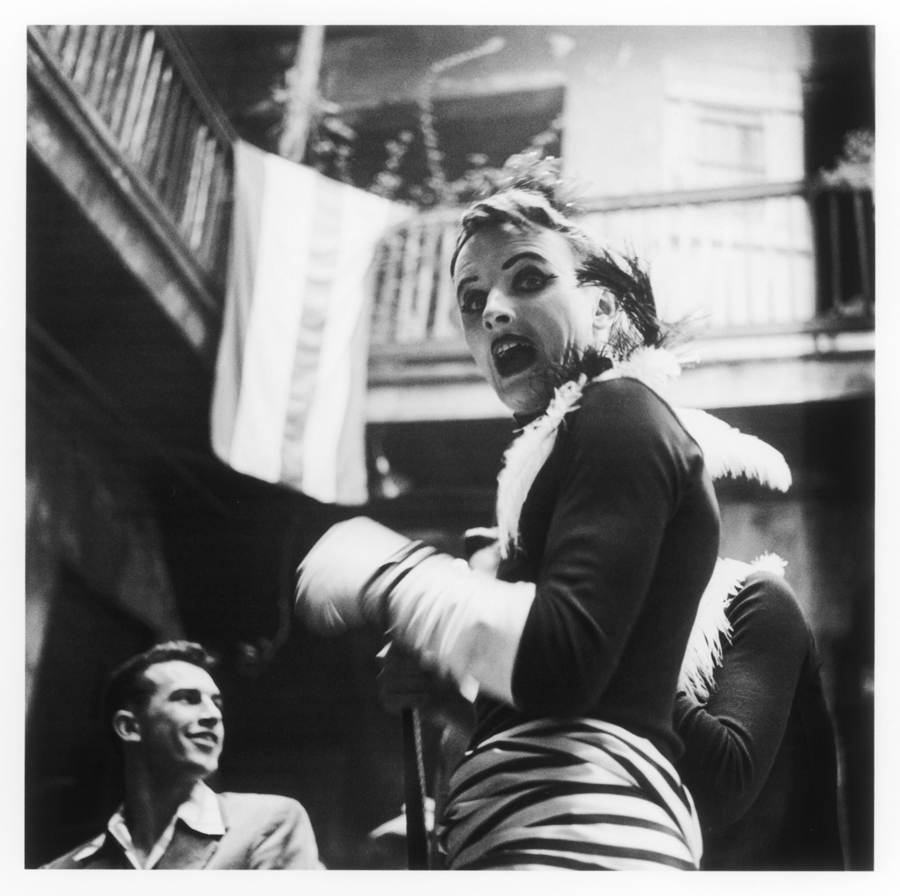

Many of Robinson’s friends and colleagues, male and female, were homosexual or bisexual, and Robinson’s images provide a window into 1950s gay lifestyles and cultures of creativity. Photographs of friends and the man with whom Robinson had an intimate long-term relationship in New Orleans and New York illustrate their lives and reveal their influence on Robinson as an artist and an individual. With his camera, Robinson documented the tensions between gender and sexual identities and the desire for free, open, creative self-expression in the South during the McCarthy Era.

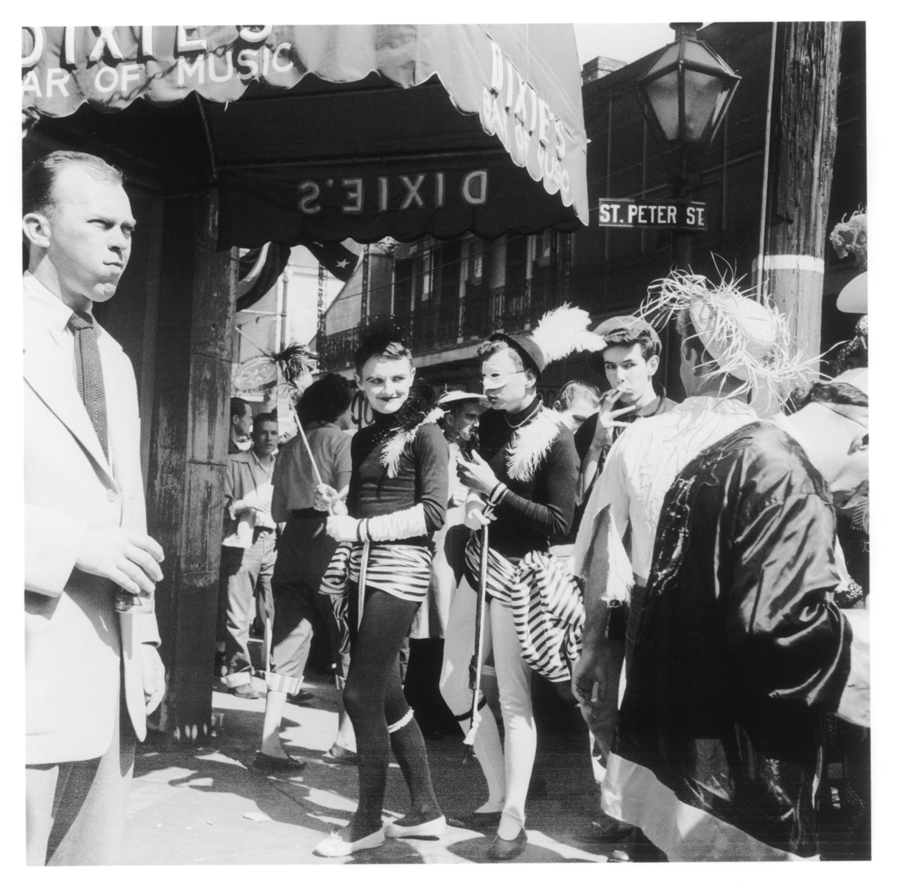

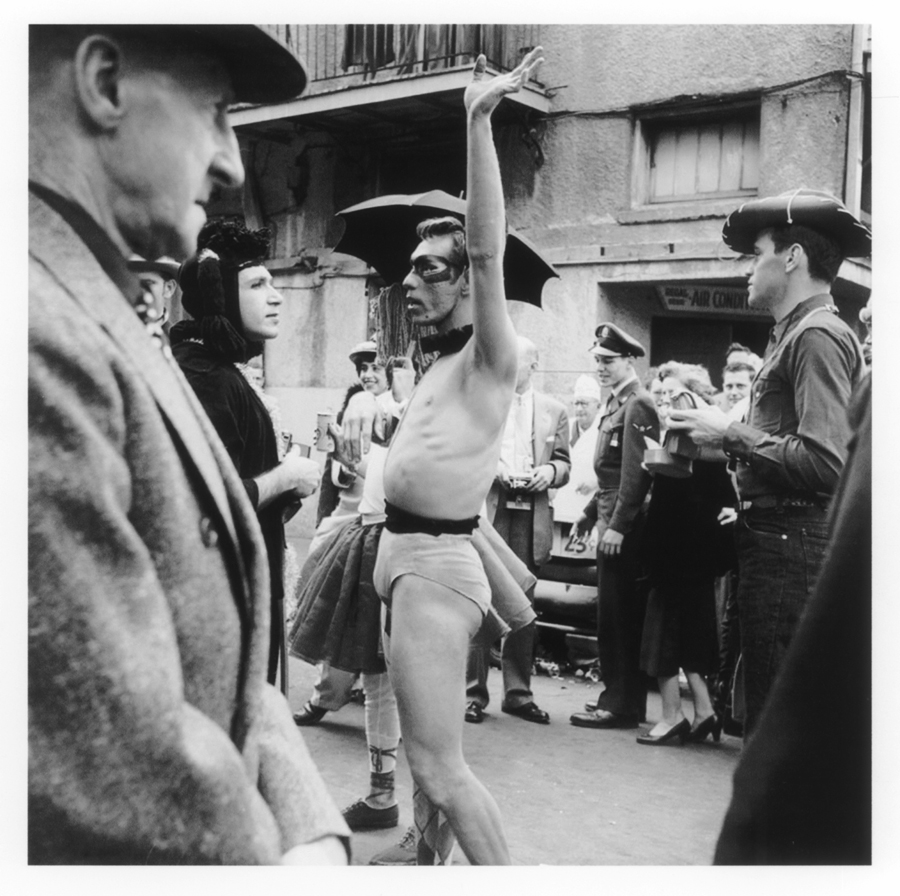

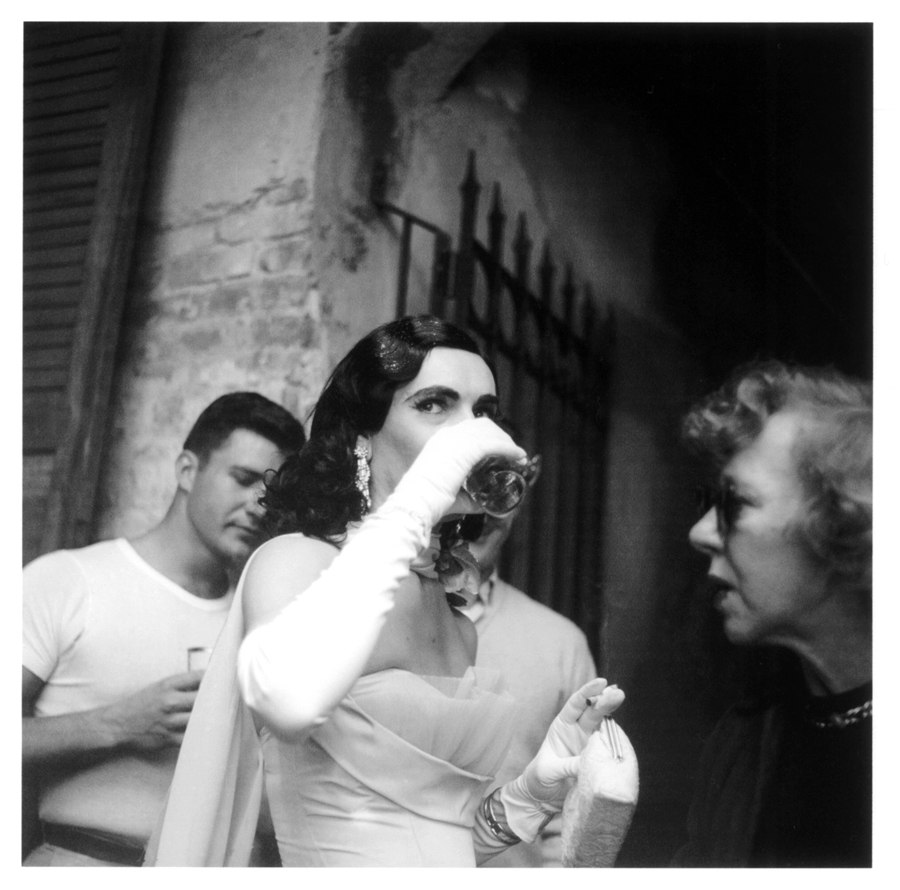

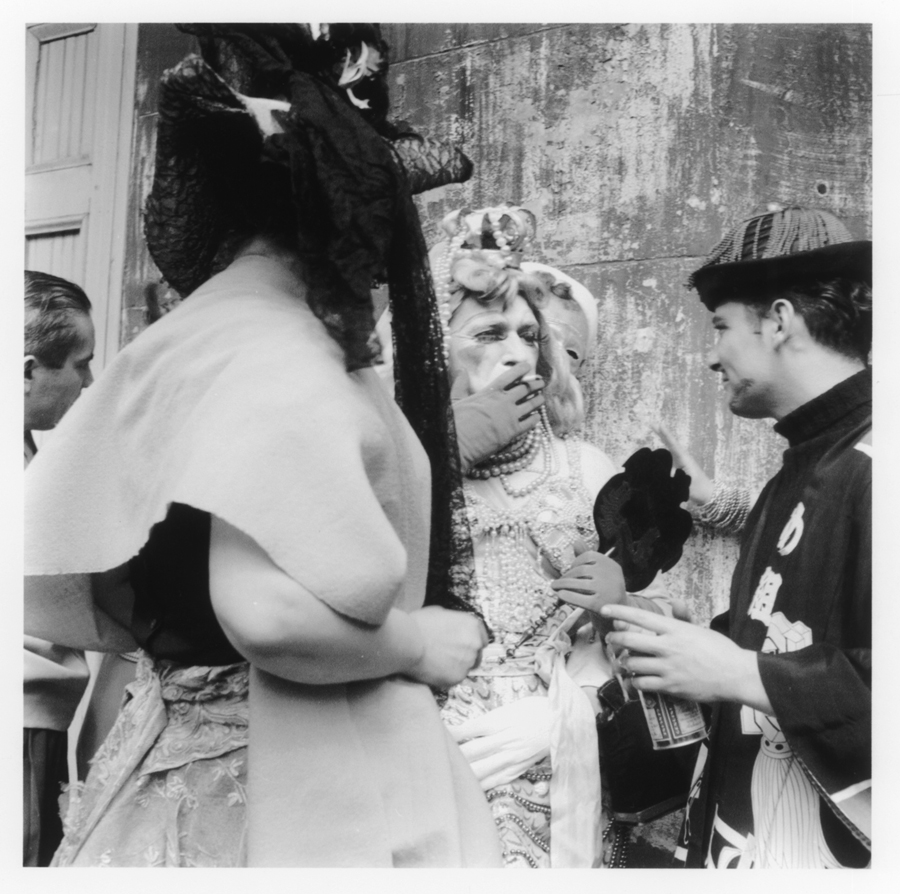

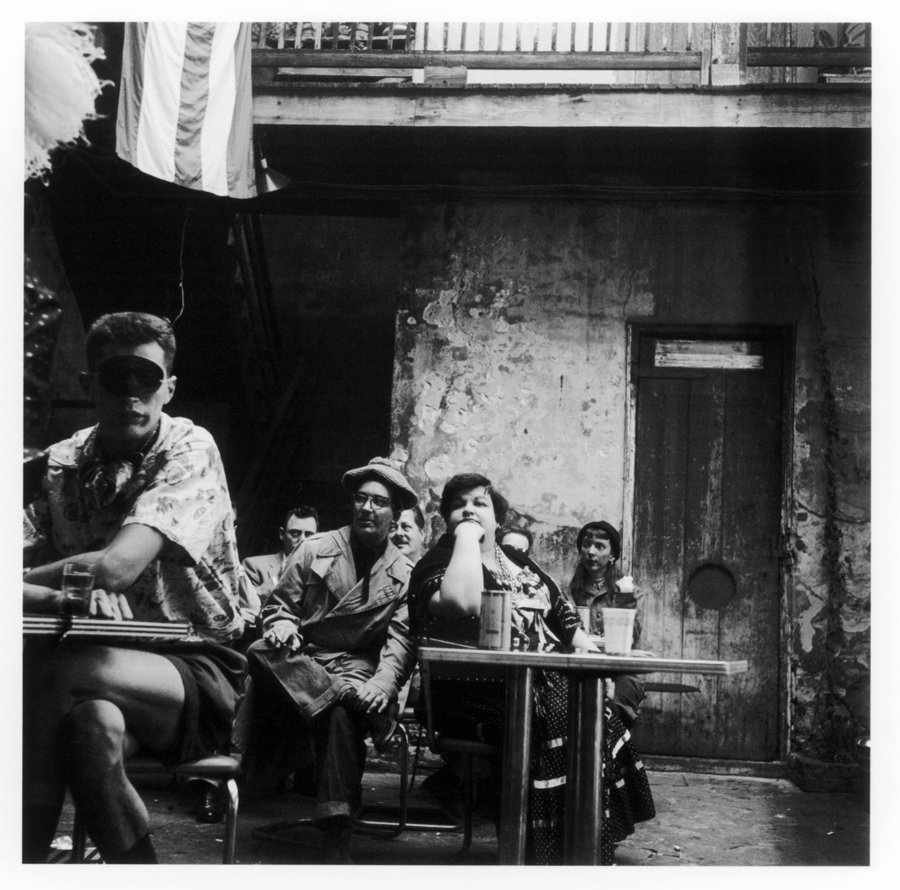

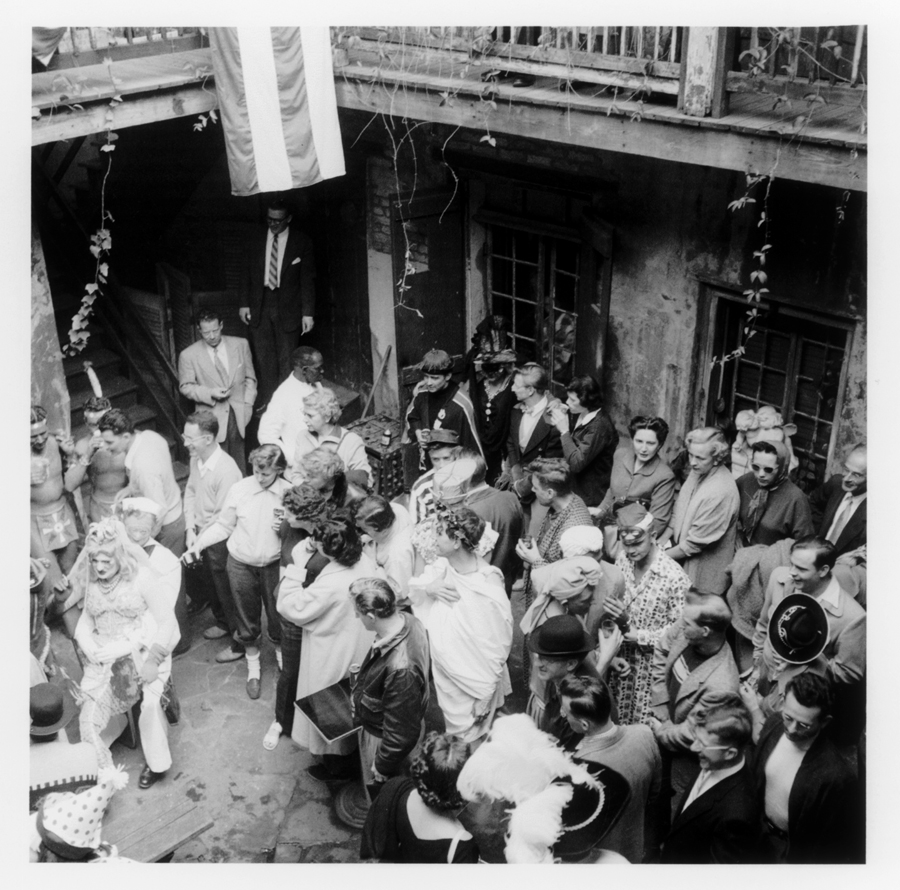

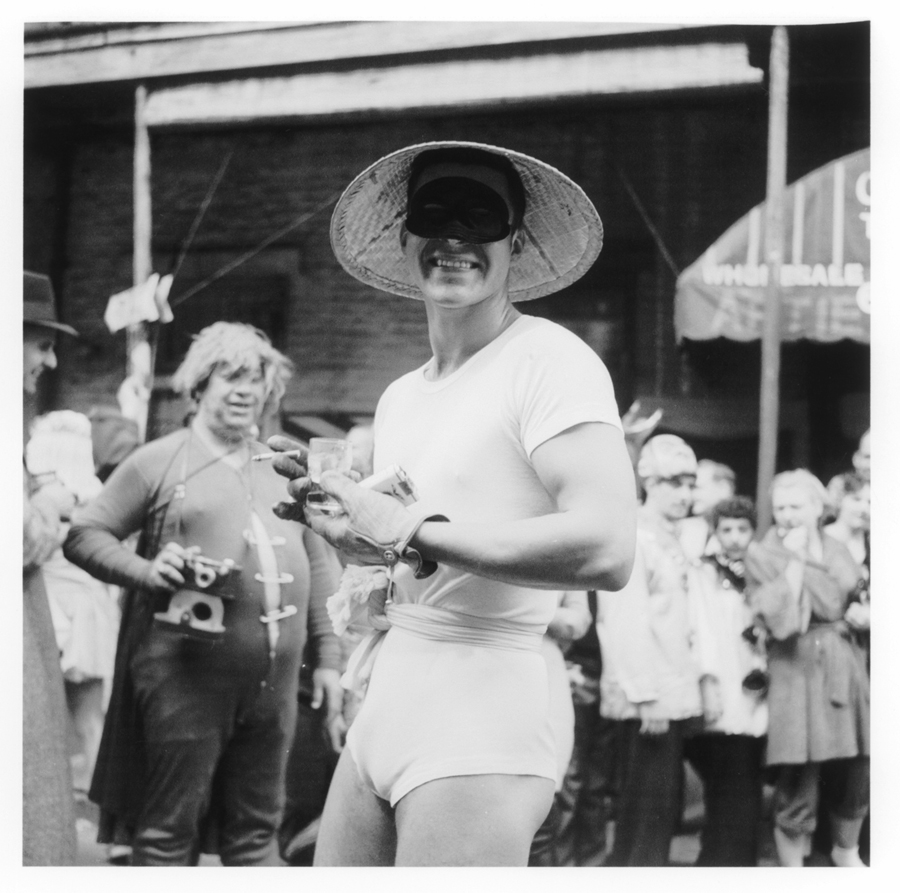

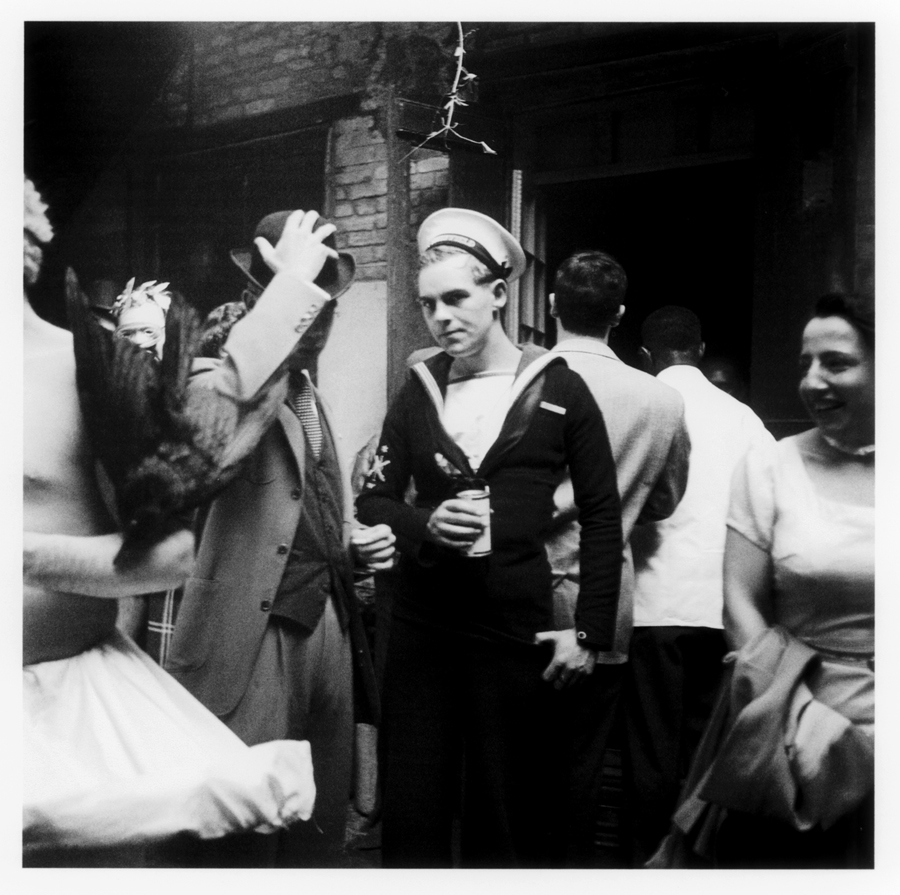

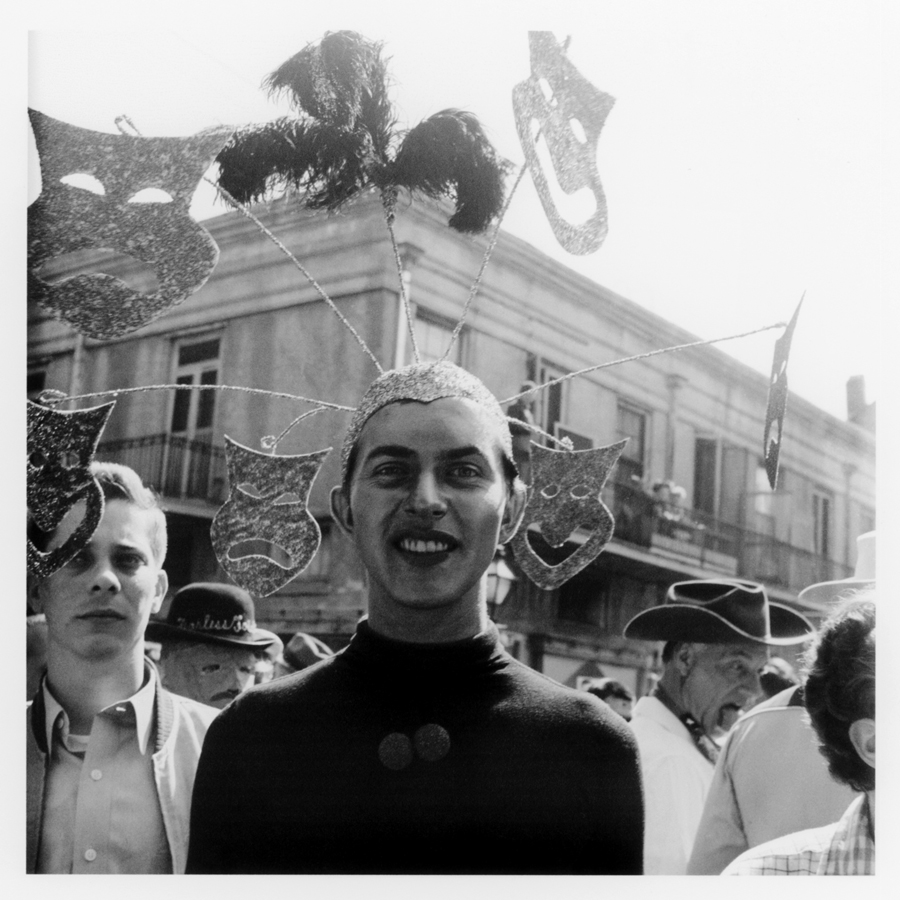

Robinson’s Mardi Gras photographs taken between 1952 and 1955 featured this determined self-expression, especially the bold visible challenges to conventional looks, lifestyles, and behavior as his subjects paraded through the public streets and partied in the courtyards of the Quarter. The collection includes photographs of one or two floats, Zulu kings and their courts, and gowned and crowned Mardi Gras queens, but the majority of the negatives reveal amazing scenes of Fat Tuesday revelers in the vicinity of Dixie’s Bar of Music, located at the corner of Bourbon St. and St. Peter St. in the French Quarter. Dixie’s, a legendary hangout for artists and writers, notably Lyle Saxon, Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, and Gore Vidal, is considered one of the first gay bars in the city and an important part of the modern history of gay New Orleans. The photographs included here not only capture the campy artistry that Dixie’s patrons used to mock convention, but they show how important the club was as a center of social life for the denizens of the French Quarter and their kindred spirits.

When I interviewed the artist Jean Seidenberg, who knew Robinson in New Orleans, Seidenberg’s wife Charlotte mentioned that the owner of Dixie’s Bar of Music, Dixie Fasnacht, still lived in the Quarter. Yvonne “Dixie” Fasnacht, locally known as “Miss Dixie,” was soon to celebrate her ninety-fourth birthday. She agreed to look at photographs and talk with the Seidenbergs and me about the years when Robinson focused his lens on Fat Tuesday at Dixie’s.

At Home At Dixie’s

To understand the appeal of Dixie’s, it is important to know the history of Dixie and her club.3 Fasnacht was born in New Orleans in 1910 and grew up frequenting the French Quarter, where her mother’s family lived. Her father’s family had been in the region since the 1840s, when several brothers emigrated from Switzerland and later opened Fasnacht Brothers brewery in 1852, the first in New Orleans. During prosperous times, they also owned plantations. The brewery failed in the aftermath of the Civil War and was sold in 1876, but the postwar generation of Fasnacht brothers, including Dixie’s father, stayed in the liquor business by owning saloons and tending bar. Her mother’s father was from France, and her maternal grandmother’s family, of white creole Louisiana descent, owned plantations before the war. As a young woman, Dixie’s mother lived in a house at the corner of Ursaline and Dauphine in the heart of the Vieux Carré district. By the time Dixie was born, the youngest of three children, the families had long ago sold their plantations and possessed only a few material reminders of wealthier days.

Dixie grew up as a “downtown girl” in what had become working-class neighborhoods. Her mother died when she was only eight, and her older sister Irma took over the care of Dixie and their brother while their father worked as a head bartender in the best saloons and hotels in New Orleans. Considering the family heritage in the liquor and saloon trade, it is not surprising that Dixie’s generation of Fasnachts continued on the same path.

The Quarter was part of her family history, and the lively, often raunchy boogie woogie and jazz music that played in its clubs and halls fascinated Dixie as a child. The powerful rhythms and creative styles inspired her to be a musician. Because Dixie’s love of music and art distracted her from her schoolwork, Irma enrolled her nine-year-old sister in the Francis T. Nicholls School so that she could study music. Dixie’s father bought her an Albert-style clarinet, one of the few wind instruments he could afford. Dixie loved the sound and began playing by ear the music she heard in local clubs. A trio of talented sisters, Martha, Helvetia, and Connee Boswell, also attended Nicholls, and the Boswell girls and Dixie hung out together in the evenings listening to jazz bands around town. As a vocal trio, the Boswell Sisters became a sensation, and their popularity opened the way for other white female jazz ensembles.

When the Boswells broke into radio and recording, Dixie had been performing locally with other female musicians from Nicholls. In the 1930s, she led all-female jazz ensembles that were popular around town, especially after Prohibition ended in 1933 and club patrons, as Dixie explained, could get decent liquor to drink. Dixie’s group, the Southland Rhythm Girls, went on the road, playing in Chicago and New York, and eventually making their way to California, where they performed in a motion picture short.

Dixie’s father died in 1937, but her sister Irma was already earning a fairly good, independent living as the proprietor of the Little Ritz, a red-beans-and-rice restaurant and bar. In 1939 Irma opened Dixie’s Bar of Music at 204 St. Charles St., and Dixie came home to help “Miss Irma,” as she called her sister, run the club.

Dixie’s offered some of the best live jazz and swing music in town, featuring performances by Dixie and her piano player Dorothy Sloop, whom Dixie nicknamed “Sloopy.” (Sloop’s name was immortalized in the early 1960s song “Hang On, Sloopy,” after two New York songwriters found inspiration in a lively evening at Dixie’s.) The place became popular because of the music, Dixie’s charm, and its unique décor. One particularly enthusiastic regular, Lyle Saxon, suggested that the women commission Xavier Gonzalez, a gifted artist teaching at Newcomb College, to paint a jazz mural on the bar’s interior walls. The club’s magnificent artwork (now located on the second floor of the Old Mint) and swinging music especially appealed to what Dixie called “the cufflink set,” men whose dapper and flamboyant personal styles and sexual personas tended to attract other men. After Irma and Dixie moved the club to 701 Bourbon St. in 1949, starving artists, entertainers, and theater people were added to the mix. Dixie’s doors were wide open, and the club never had a cover charge. The southern bohemians of the Quarter loved Dixie’s, and the Fasnacht sisters were grateful for their clientele’s loyalty.

According to Dixie, she and Irma did not set out to run an establishment that particularly drew gay men—”It just happened like that!” The club’s relocation to the French Quarter gave Robinson and his friends a place where they could enjoy themselves, be themselves, and be together without fear of judgment. Dixie’s own celebrity and her family’s long history in the region allowed Dixie’s to thrive unmolested until the sisters retired in 1964. By her own admission, Dixie’s was “the cleanest bar in town, on Bourbon St.,” and it soon became an institution.

Robinson’s photographs of Fat Tuesday at Dixie’s make a statement about the open, gay-friendly atmosphere that emanated from Dixie’s interior courtyard and bar and spilled out onto the street and the corner where Dixie’s awning hung as a backdrop. These images are remarkable, not only for their clarity, composition, and subject matter, but for what they show of the spectators’ tolerance of what was really, in many cases, gay performance art. Cross-dressing was illegal in Orleans Parish except on Halloween and Mardi Gras, although municipal court dockets from the fifties show little evidence of enforcement the rest of the year. The era is known for its intolerance of homosexuality, illustrated by campaigns to purge gay men and women from the military and government. Robinson’s photographs of Fat Tuesday at Dixie’s show another side of American life and culture, one that challenges the perhaps overdrawn history of the McCarthy Era as largely devoid of acceptance of homosexuality. Dixie told me that her place had never been raided or her patrons bothered by the police while at Dixie’s. Indeed, court records show little more than signage infractions associated with Dixie’s. Her place was identified in a 1953 citizens’ vice commission report as a known homosexual hangout, but no substantive action followed the divulging of what was already well known to local authorities.4

Dixie and Irma Fasnacht, whose last name means “carnival” or “festival” in Switzerland, showed their appreciation to their customers and friends on Fat Tuesday by preparing a special spread. They hired extra help to handle the increased business as out-of-towners also converged on Dixie’s for what became for many an annual pilgrimage.

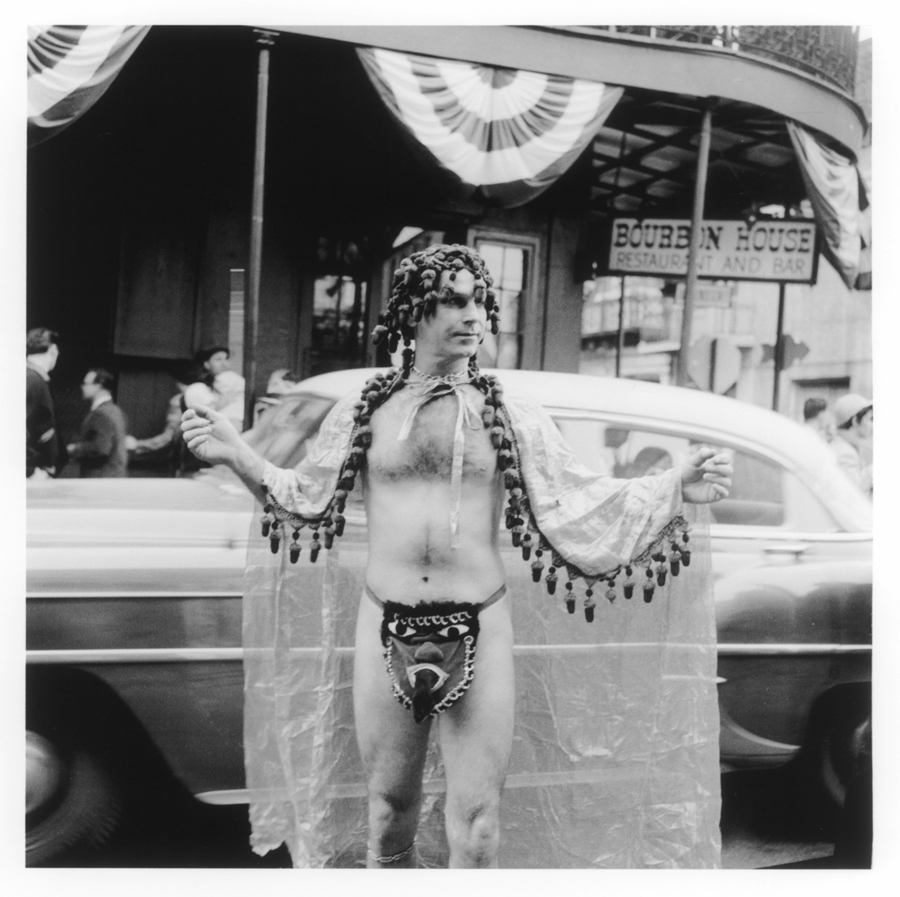

Robinson used only natural light at Dixie’s, giving us scenes of the courtyard and the corner around Dixie’s awning but no photos of the club’s interior, which would have shown Dixie behind the bar, Irma at the cash register, and the famous Gonzalez mural. In the photographs, patrons relax in the courtyard drinking cocktails and jax beer. Looking down from the courtyard balcony, Robinson captured a crowd of elaborately costumed young men celebrating amidst men and women in plain clothes and some men in military uniforms. A few older men, such as the well known Royal St. antique dealer, Elmo Avet, made a great effort to fashion extraordinary costumes. Avet’s sequined mermaid costume (with sailor manikin attached) attracted tremendous attention, which was, of course, the point. Robinson followed some subjects as they milled around the entrance and walked down Bourbon St., socializing along the way. Also captured in the courtyard scenes were the black men Dixie hired to help serve the crowd—the only African American men photographed in the courtyard. Jim Crow was the law in and out of the French Quarter, but in the streets the crowds became more racially diverse.

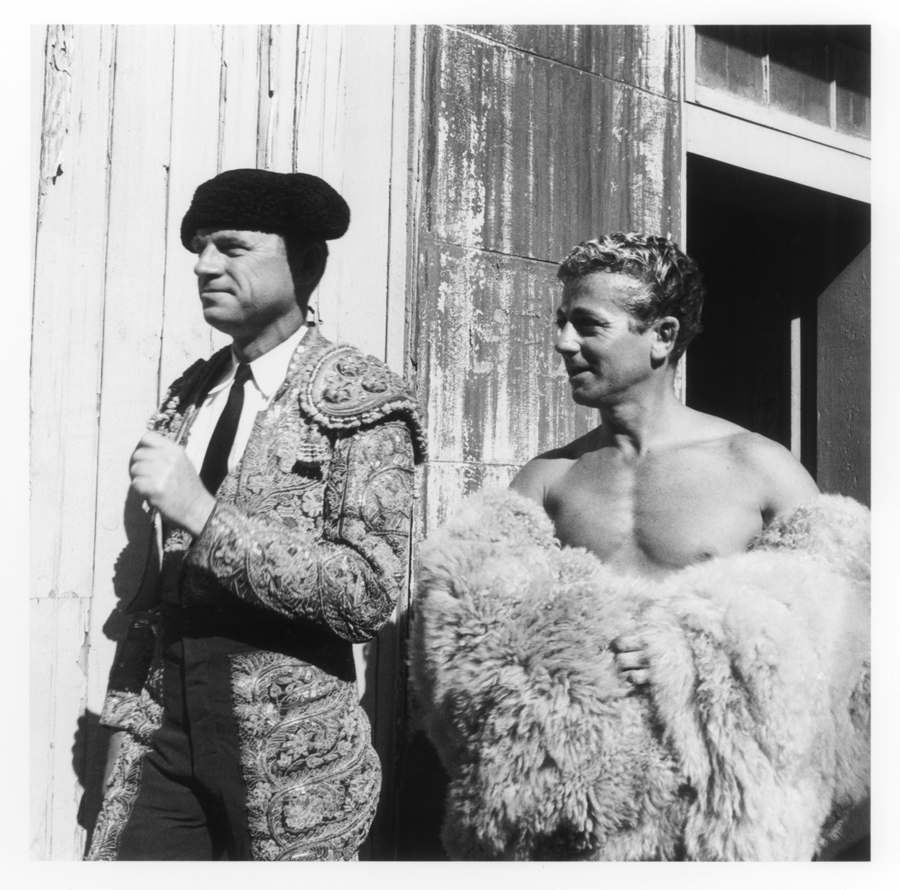

Masks, costumes, and fanciful makeup confounded our efforts to identify many individuals. Fat Tuesday in the Quarter attracted men from distant regions. As Dixie observed of one especially flamboyant young man, “For all you can tell, he could be from Oshkosh!” But in a photo featuring a man holding a fencing foil and wearing only sheer black tights, Dixie recognized the distinguished white-haired gentleman standing next to him wearing a toga. “That’s Clay Shaw!” Jean Seidenberg, who painted a portrait of Shaw, agreed. Shaw was a popular, homosexual New Orleans real estate developer and preservation activist. He became national news in 1969, when District Attorney Jim Garrison accused him of leading a circle of gay men from New Orleans who, Garrison was convinced, orchestrated the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Shaw became the only person in history to be tried for the Kennedy assassination, and, although Shaw was not convicted, he never recovered from the investigation that thrust him, his personal life, his homosexuality, and his friends into the spotlight. But in Robinson’s 1950s photos, Shaw appears triumphant and proud. Like Dixie, he cared deeply about the welfare of the Quarter.

In conversation, Dixie often referred to the habitués of the club as “my boys,” and local authorities seemed to show a certain respect for Irma and Dixie by leaving their “boys” alone. In 1958, three years after Robinson left New Orleans, local gay men, including a number of Dixie’s regulars, organized the first openly gay Mardi Gras krewe. When Krewe of Yuga held a ball in a parish outside New Orleans in 1962, police raided the party. A few krewe members escaped and came into Dixie’s with the news. She contacted a lawyer and bailed her “boys” out of jail.

But the spirit of Fat Tuesday at Dixie’s continued in the gay Mardi Gras parades and the proliferation of self-identified gay krewes, institutions established years before the 1969 Stonewall riots in New York that mark the beginning of the gay movement.

Two years later, in 1964, Dixie and Irma sold Dixie’s Bar of Music. But the spirit of Fat Tuesday at Dixie’s continued in the gay Mardi Gras parades and the proliferation of self-identified gay krewes, institutions established years before the 1969 Stonewall riots in New York that mark the beginning of the gay movement. Many years later, the local community recognized Dixie by honoring her among the first recipients of the New Orleans’ Gay Appreciation Award for lifetime achievement.

It is perhaps ironic that Clay Shaw, his friends, and Dixie’s Bar of Music have been immortalized in 1960s reports in which FBI investigators treated the fact that Shaw’s associates met at Dixie’s as suspicious—as though there had to be something treasonous about a place so free and open and accepting of homosexuals and creative people. Robinson’s photographs give us something of an antidote to the smearing and demonization of homosexuals sanctioned and encouraged for political gain by government officials. Before the assassination of a president, before the rise of the homophobic radical right, before AIDS and the crucifixion of Matthew Shepard, very southern gay men in a very southern place happily celebrated their identity and their community. Robinson’s photographs captured a history that proudly exposes their liberty, individuality, fraternity, and, above all, their joy.

At Dixie’s insistence, before we left her home, we all shared a cold beer. “Drink to all the lovely people that we knew,” she said. “Good people are hard to find.” Our glasses clinked, “Here we go. Drink to them!”

Sarah Wilkerson-Freeman is associate professor of history at Arkansas State University. She has published numerous chapters and articles on gender and women’s history in the South, including in Mississippi Women: Their Histories, Their Lives. She is currently planning a book on photographer Jack Robinson.

Special thanks to The Jack Robinson Archive, LLC, for granting rights to publish Robinson’s photos onlineNOTES

Some of the information and images published here were first presented at the Southern Historical Association’s annual meeting in Memphis, Tennessee, on November 5, 2004 (Sarah Wilkerson-Freeman, “Jack Robinson’s Southern Scenes”).

I would like to thank Dan Oppenheimer, Drue Diehl, Gary Walpole, and the associates of the Jack Robinson Gallery and Archive in Memphis for their enthusiastic cooperation and permission to use Robinson’s photographs in publications and presentations. I especially thank Dixie Fasnacht, Jean and Charlotte Seidenberg, Charles Dolce and his family, George Dunbar, Lennard Parrish, Lyle Bonge, Lee Hall, and Alan Helms for sharing their insights into Robinson’s early life and the 1950s New Orleans’s art scene. Pamela Tyler, Erik Neil, Leslie Pharr, and Craig Leake deserve special thanks for their interest and encouragement, as does Arkansas State University for its generous support of this project.

- For more on the discovery of Robinson’s work and his career in the 1960s, see Brandon Thornburg, “Jack Robinson,” Gamut (October 2002): 34–41.

- Conversation with Dan Oppenheimer, Jack Robinson Gallery, 44 Huling Avenue, Memphis, Tennessee, 5 October 2004.

- The majority of information on the history of the Fasnacht family and Dixie was provided by Dixie Fasnacht in the course of our interview in her home on Bourbon St. in June 2004. Details and corroborative information were drawn from census records, city directories, Louisiana and New Orleans history and preservation sites, and an article on New Orleans jazz women by Sherrie Tucker (“Rocking the Cradle of Jazz,” Ms. Magazine, Winter 2004), published after I conducted the Fasnacht interview.

- New Orleans Municipal Court Docket Books, 1949–52, located in the third-floor attic of the New Orleans Municipal Courthouse. Arron M. Kohn, chief investigator, Investigative Report, 15 October–28 July 1953, box 4, folder 9, 7–6, Special Citizens Investigating Committee Papers, Special Collections Division, Jones Hall, Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana. A special thanks to Pamela Tyler, New Orleans historian and associate director of the Deep South Regional Humanities Center at Tulane University, for directing me to this important source.

Read More About It

For more on male homosexuality in the 1950s and in the South, see John Howard, Men Like That: A Southern Queer History (University of Chicago Press, 1999); John Loughery, The Other Side of Silence, Men’s Lives and Gay Identity: A Twentieth-Century History (Henry Holt and Company, 1998); and Alan Helms, Young Man from the Provinces: A Gay Life before Stonewall (University of Minnesota Press, 1995).

For more on homosexuality and visual representation in this period, see Richard Meyer’s Outlaw Representation: Censorship and Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century American Art (Beacon Press, 2002). Numerous essays by New Orleans author and activist Jon Newlin, published in AMBUSH Magazine, provide useful insights into the history of gay New Orleans and residents of the French Quarter.

Mardi Gras, French Quarter life, and photographic histories of both have received significant attention from authors and scholars. A few relatively recent publications include Henri Schindler, Mardi Gras: New Orleans (Flammarion, 1997); Carol Flake, New Orleans: Behind the Masks of America’s Most Exotic City (Grove Press, 1994); and Alecia Long, The Great Southern Babylon: Sex, Race, and Respectability in New Orleans, 1865-1920 (Louisiana State University Press, 2004).

Many American authors drew inspiration from New Orleans. Lyle Saxon published The Friends of Joe Gilmore (1948). Tennessee Williams wrote A Streetcar Named Desire (1947), Suddenly Last Summer (1948), and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955) in New Orleans. Williams won Pulitzer Prizes for both Streetcar Named Desire and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. The screen version of Streetcar was filmed in New Orleans in 1950. Truman Capote, a New Orleans native, lived in an apartment at 711 Royal St. while writing Other Voices, Other Rooms (1945). Gore Vidal, who frequently socialized with Williams and Capote, set many of his early fictional scenes in the French Quarter and published The City and The Pillar in 1948.