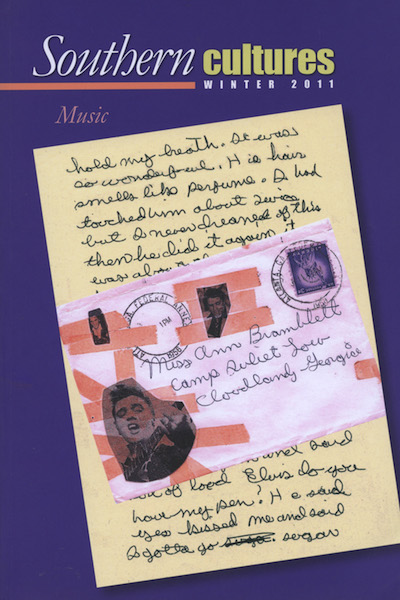

“Record selling certainly had its glamorous moments; retailers could regale younger customers with stories of nightlife and even rubbing elbows with famous musicians and celebrities.”

“Records is a market that can be used to brighten the future of lots of black people with jobs and higher prestige all over the country,” Jimmy Liggins announced in 1976 to the readers of the Carolina Times, Durham, North Carolina’s most prominent African American newspaper. Liggins, a minor rhythm and blues star of the 1950s, was publicizing his Duplex National Black Gold Record Pool, headquartered in Durham, which sought to “help and assist black people to own and sell the music and talent blacks produce.” With the aid of this “self helping program,” aspiring hit-makers could record and release music that Black Gold sold through mail order and at Liggins’s shop, Snoopy’s Records, in downtown Durham.1

Kenny Mann vividly recalls his frequent trips to Snoopy’s as a teenager in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Liggins “was like a god” to Mann and other young customers who patronized the store. “Everybody knew” Liggins and his two business partners, Henry Bates and Paul Truitt. “These guys, I was listening to them talk about bringing Tyrone Davis and Johnny Taylor and Al Green to town . . . It was fun to go [to their store] because it felt like the place to be; there were girls in there, and I was twelve, thirteen years old.” Not only that, but Mann “never felt the pressure to buy something” like he did in stores in his hometown of Chapel Hill, where white shopkeepers frequently followed young African American shoppers around their businesses, suspecting they might shoplift. “They had a double standard,” Mann remembers. Chapel Hill “really was set up as if they didn’t want to do business with us black people.” In sharp contrast, Liggins envisioned Snoopy’s as “our mall”—a “hang out” where black consumers could buy black music in a record store owned and operated by African Americans. Black-owned record stores like Snoopy’s represented a crucial nexus where African American enterprise, consumer culture, community, and of course, music all met. And by the early 1970s, Liggins was booking and promoting shows for Mann’s band, which eventually became Liquid Pleasure, the popular Chapel Hill-based funk and soul outfit still active today.

[I]t felt like the place to be.

In the postwar United States, record stores were perhaps the place where consumers most commonly interacted with individuals who made their living from popular culture. Yet, while music writers and scholars have devoted much attention to black-oriented radio stations and record labels, we still know very little about the retail businesses from which African Americans purchased music, especially in the South. Conservative estimates would suggest that at least 400 to 500 black-owned record stores—and probably closer to one thousand—were in operation throughout the region during this period. An examination of the black-owned record stores in one southern state, North Carolina, not only reveals valuable insights about the southern marketplace for African American music, but also much about the broader role consumer culture played in southern black communities during these transitional decades. While desegregation measures were beginning to significantly alter the racial make-up of some areas of southern society, such as public schools, many African American record retailers and consumers hesitated to assimilate into white-dominated pop-music marketplaces. Black merchandisers envisioned the record trade as an arena in which African Americans could pursue a broader strategy of bolstering economic self-sufficiency and sustaining black public life. And by seeking out music from black-owned record stores, African American consumers partook in a vibrant form of commercial public life, a community-based consumer culture that welcomed shoppers regardless of their color, age, or financial means.2

African American entrepreneurship dates back centuries, but in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement, black communities in the South expressed renewed interest in harnessing business’ potential for self-empowerment. In response to business owners, politicians, and commentators who have oversold the economic benefits of African American-owned businesses, many scholars have produced strident critiques of the unfounded idealism of such boosterism. Scholars like historian Suzanne Smith argue that Motown Industries, Berry Gordy’s Detroit-based record label—which by the start of the 1970s was earning higher annual revenues than any other black-owned business in American history—neglected Detroit’s black residents and thus demonstrated “the myth of black capitalism,” echoing the famed African American sociologist E. Franklin Frazier’s skeptical assessment of black businesses. Yet, as another sociological study of black-owned businesses in the 1970s has demonstrated convincingly, “the black share of business firms in a city seems to have a substantial impact on the relative well-being of blacks in that city.” Indeed, in most municipalities with considerable concentrations of black-owned businesses, African Americans figured prominently in both local politics and in public-sector employment.3

Black business owners depended on the support and patronage of black consumers and almost always catered to the needs and desires of the surrounding African American community. Consequently, African American consumers could make suggestions about a black-owned store’s inventory, or express displeasure with its policies and practices, all without fear of retaliation or being denied service. Southern white merchants, by contrast, commonly treated African Americans as an inferior class of shoppers, if they served them at all. Even after federal Civil Rights legislation of the 1960s, many white businesses continued to offer blacks reluctant service at best. Black mom-and- pop retail businesses, however, according to the national magazine Black Enterprise, “often served to tie neighborhoods together” and frequently functioned as meeting places and message drops. They were also among the few places where black families could purchase on credit. In short, any meaningful analysis of black businesses must extend beyond purely economic considerations in order to acknowledge the many benefits small black retailers—and not just rare, multimillion-dollar corporations like Motown—provided to their communities.4

Although black-owned record stores spread across the South in the second half of the twentieth century, their stories largely have been lost or obscured. Not only have scholars and music critics overlooked the key role record stores played in music production and reception, but the few record stores that have received significant attention have been either black-owned record stores in the urban North and West or white-owned stores. Such record shops have typically piqued the interest of historians only because they were attached to more famous record labels, such as Jim Stewart and Estelle Axton’s Satellite Records store in Memphis, where they promoted releases from their record label, Stax.5

Indeed, African American consumers and retailers in the South had long escaped notice by the record industry. Not until the 1920s did phonograph companies begin to give African Americans serious consideration as consumers or retailers of recorded music. More than any single recording, Mamie Smith’s surprise hit, “Crazy Blues,” at the start of the decade revealed to white record executives the “word-of-mouth campaigns and distribution networks” that African Americans could quickly develop to support a black artist. Black Swan, Harry Pace’s short-lived record label, represented perhaps the first recording company to concentrate on attracting African American consumers and sellers, billing its products as the “only genuine colored records,” while declaring interest in retail “agents in every community.” Black Swan phonographs found their way not only to record stores, but also to virtually any retail business with a sizable black clientele that Harry Pace could find, including drug stores, barbershops, and pool halls. Even Pullman porters were known to sell 78s to African Americans working and riding the rails.6

Jim Crow shaped the market for African American music in surprising ways. Many southern white record sellers initially resisted selling “race records” for fear of attracting black customers, which they thought would scare away their white customers. But quite a few white record sellers came to serve blacks, many of them reluctantly, and with some even insisting on establishing separate entrances and even listening booths for blacks and whites. The most powerful form of segregation in the pre-war southern music market, however, came from the record labels themselves, most of which were based outside the South. As historian Karl Hagstrom Miller argues, record labels feared alienating white record sellers in the South with recordings by black artists, so they took several measures that made it easy for any retailer to sell music exclusively by white performers. By separating their advertising campaigns, display materials, and even catalogues along racial lines, major labels effectively “segregated the sound” coming out of the South in the early twentieth century. By the 1930s, however, few Americans—especially African Americans on the lower rungs of the economic ladder—could afford to buy records. Depression-era sales plummeted, and the industry lost over eighty percent of its sales between 1927 and 1932. Only in the early 1940s did the national music business and press, most of it based in New York and Los Angeles, give much attention to African American music consumers again, but in doing so it largely ignored southern blacks. The music business trade journal Billboard initiated its first chart of African American record sales without even considering sales in the South. In 1942 it launched the so-called Harlem Hit Parade, which drew its sales reports from just six record stores located in uptown Manhattan. While intended to convey the musical tastes of black Americans, the chart instead revealed the white music industry’s regional myopia. In later years, the magazine would cast its black music chart in more regionally ambiguous terms (including Race Records, Rhythm and Blues Records, Hot Soul Singles), renaming it ten times in six decades.7

The music business trade journal Billboard initiated its first chart of African American record sales without even considering sales in the South. In 1942 it launched the so-called Harlem Hit Parade, which drew its sales reports from just six record stores located in uptown Manhattan.

Arguably, it was not until the 1970s that African American record stores began to receive the attention they deserved from the music industry. In 1976, African Americans launched two nationally distributed trade publications devoted to black radio and black music retail. The famed radio DJ Jack Gibson, working out of Orlando, founded Mello Yello, which for years proclaimed itself the first black trade publication of any kind, and in Los Angeles, former Capitol Records A&R and promotions man Sidney Miller founded Black Radio Exclusive. Both of these publications emphasized the significant effect that strengthening the black music industry would have on black communities. As one writer for BRE told readers,

The R&B industry is made up primarily of black people; so therefore, we cannot talk about the needs of the industry without talking about the needs of black folk. And what the industry and black folk need most today is POWER! There are many types of power that are included in these needs, the most obvious of which is a type of economic power.

African Americans who patronized black-owned music businesses and listened to black-format radio, the writers of bre argued, enriched their communities and stimulated local black economies.8

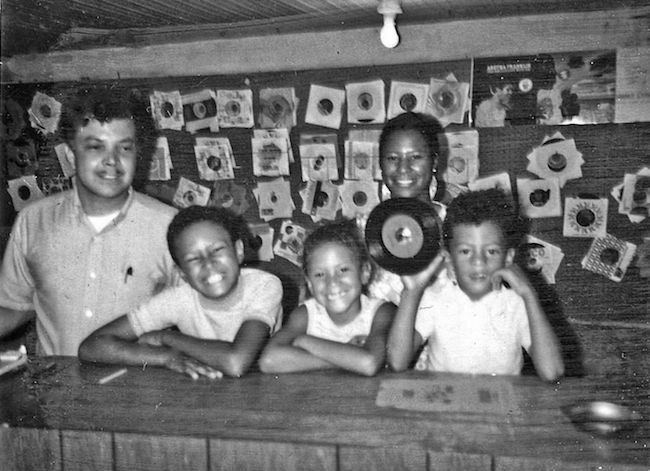

In terms of retail trade, very few businesses enjoyed greater popularity among African American consumers than record stores. According to one African American record distributor, “every black man thinks that the first business they could go into are records, because that’s something we all know, and that’s the thing that’s closest to us.” A survey of Harlem’s commercial district on 125th Street in 1970, for instance, showed there were six record stores within a stretch of three blocks, outnumbering all retailers in the area except for general merchandisers, “lunchrooms,” and beauty supply stores. In fact, the very first black-owned business on Harlem’s 125th Street was Bobby’s Happy House, which the late South Carolina native Bobby Robinson opened in 1946. Yet it was the South—where one could find nearly half of the nation’s African American retailers and a slim majority of the sales of music by black performers—that was almost certainly home to the lion’s share of the country’s black-owned record stores. North Carolina alone boasted at least fifty black-owned record stores, and probably closer to one hundred, in the 1960s and 1970s. Larger cities like Charlotte had half a dozen or more such shops over the course of these decades, while even some small towns like Shelby and Maxton had more than one black-owned record store. Records, according to the famed music merchandiser Sam Goody, were a “poor man’s luxury.” They were relatively inexpensive: singles cost between fifty cents and a dollar, while LPs usually sold for five to seven dollars.9

Black-owned record stores epitomized what sociologist Ray Oldenburg calls “third places,” informal and often commercial gathering places where patrons could shop, interact, and take part in a communal process that might be best described as social consumption. And by the late 1960s, black-owned record stores were beginning to play new community roles within the context of a slowly desegregating society. Although there was strong support for desegregation in the black community, many African Americans were unhappy with how the process favored white institutions—especially in education, as countless black public schools closed their doors and thousands of black educators and administrators were fired. Consequently, countless black students lost not only their schools’ mascots and traditions, but also their role models. School desegregation, while touted as a campaign to bring together students of different races so that they could share educational opportunities and facilities, often required black students to abandon the culture of their schools in order to assimilate into white-dominated schools. Naturally, many African American Baby Boomers, born between 1946 and 1964, found it quite challenging to adjust to the loss of black public schools. Black students of the era recall facing outright resentment, frequent interracial fighting with white students, and high rates of suspension. Kenny Mann remembers how “a lot of the white teachers [at newly desegregated schools] had this preconceived notion that we couldn’t do certain things.” For Mann, black-owned record stores like Snoopy’s functioned as invaluable black public spaces within the context of school desegregation. Jimmy Liggins showed respect to the young African Americans who patronized Snoopy’s, not only by making them feel welcome in his store, but also by holding them to a high standard of behavior. “I couldn’t pull half the jive on Jimmy Liggins that I pulled on my white third and fourth grade teachers,” Mann explains. Liggins and his clerks “didn’t fall for any of the stuff we did; they were not going to let you act up” in their store. Black record dealers offered young African American consumers safe, structured spaces where they could partake in a black-oriented, commercial public life.10

With a growing sense in many southern black communities that desegregation, while fully necessary, had been implemented in a manner that favored white-dominated institutions, support for black business flourished in the South in the late 1960s and 1970s. Claude Barnes, then a teenaged Black Power activist from Greensboro, remembers how even as desegregation was accelerating in his hometown, he still felt that “the black business community was ours.” According to one survey, roughly two-thirds of African American high school juniors believed that governmental authorities “were unaware of black problems,” yet a majority of those students felt that black entrepreneurs were able and obliged to advance black communities’ economic and social interests. Large majorities of black teenagers in the South—more so than in any other region—expressed the dual desires to “be successful in business” and to “help black people.” Although American teenagers’ views of capitalist enterprise had worsened steadily since the 1950s, one survey from 1971 reported that more than half of black teenagers, compared to just over one-third of white teenagers, viewed American business in positive terms.11

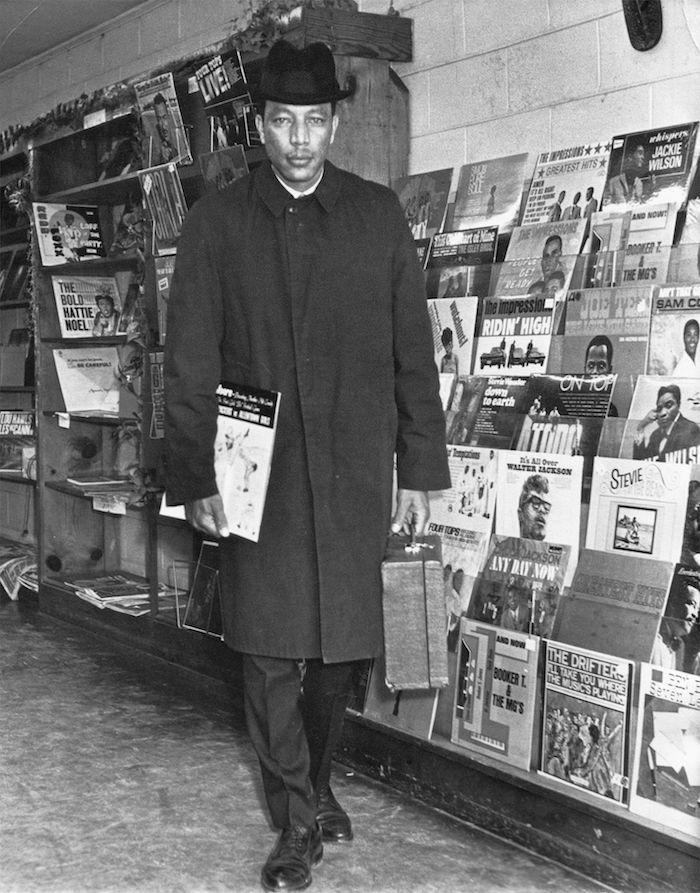

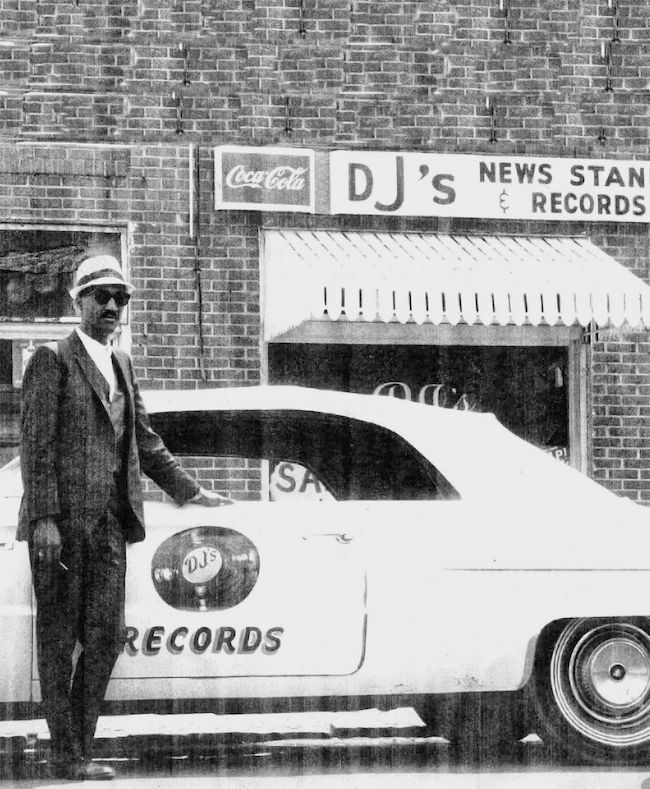

African American consumers flocked to black-owned record stores in the 1960s and 1970s, which represented the heyday for North Carolina shops like Curt’s Records in Greensboro, DJ’s Record Shop in Goldsboro, Snoopy’s in Durham, and Washington Sound in Shelby. These stores’ clientele were almost entirely African American and often young. Calvin Wade, who frequently visited Bill Hester’s record store Rozena in Mebane, recalls the shop as a “community area. Everybody knew everybody. You’d see people, you’d have a conversation.” On Saturdays, “all the high school kids went there . . . Most black people went there because it was our side of town.” In the late 1960s Daniel Adams felt strongly that “we needed a black record store” in Goldsboro, so he opened DJ’s Record Shop and News Stand, where customers could buy the latest issues of Ebony as well as the newest soul hits over coffee and donuts at a bar inside the store. Most black-owned record stores were located in traditionally African American business districts—East Market Street in Greensboro, Sugar Hill in Kinston, the James Street corridor in Goldsboro (known as the Block), and the Buffalo Street corridor in Shelby—but they drew customers from surrounding areas as well. At Curt’s Records, customers came from all over Greensboro and as far as twenty miles away from towns like High Point and Reidsville, especially on Saturdays, when people would stand in line to buy their music. “Every weekend there were a few new hits—and they were hot,” Curt Moore recalled. Indeed, in the second half of the 1960s and the 1970s, the record industry as a whole experienced an unprecedented boom period.12

These shops’ stock in trade was usually soul and R&B, but they also sold jazz and gospel as secondary genres. Stores like James Thomas’s Soul Shack in Raleigh specialized in gospel, and there were also stores that focused on jazz, typically in larger cities. Big-selling Motown artists like the Temptations, Stevie Wonder, and the Jackson Five were easy to find at white-owned stores. But as Kenny Mann explains, at the white-owned record stores in his native Chapel Hill, “most of the stuff was so sanitized, when we wanted to get funky, we had to go find those records” at Snoopy’s in Durham, where one could easily purchase music by artists like Curtis Mayfield, Johnny Taylor, Joe Tex, and James Brown. Black record dealers prided themselves on offering black artists’ recordings before they were available at other stores; as the motto of Curt’s Records suggested, one could “find the hits first at Curt’s.” In general, the clerks and merchants at black-owned stores simply were much more familiar with African American music and black musical tastes than their white counterparts were. Store-owners’ advertisements on black radio stations and their personal connections to DJs provided ties to labels and distributors, who maintained close relationships with record companies. Consequently, black record dealers sold a great deal of music about which many white record sellers were oblivious or indifferent. Beyond music, many stores also sold black-oriented wares such as black hair products and daishikis.13

Most of the stuff was so sanitized, when we wanted to get funky, we had to go find those records’ at Snoopy’s in Durham.

Years later, customers and merchants alike vividly recall the powerful sights and sounds of these record stores. Many merchants placed speakers outside their stores to blare the latest hits to passersby. At Curt’s, people in the adjacent stores, in the strip’s parking lot, and in passing cars could hear the music, so that even when shoppers were “trying to go home, they’d still have a song in their heads.” More than a few customers spontaneously decided to go into Moore’s shop and purchase a record after hearing it play from his speakers outside. Fred Waddell, who grew up in Wilmington in the 1960s, remembers one black-owned record shop from his hometown vividly. The store was “very narrow. You walked into the door and the cash register was immediately to your side. Then you had a little aisle way, and all these posters were in the back, advertising different artists, upcoming shows, who’s coming to town.” Many of the posters in these stores that featured female acts “made the girls look sexy,” as Calvin Wade remembers fondly. At smaller, independent stores, racks of record sleeves lined the walls, while larger shops might store all their wares in bins. Waddell describes the store he patronized as having a catalogue system, where records were arranged alphabetically but without the name cards commonly found at bigger stores; all music was positioned in clear view of the clerk, who stood on a raised platform behind a counter, where the “hot stuff” was stored. At some stores, only clerks handled merchandise prior to purchase. “We didn’t have self-service,” George Bishop of the Mr. Entertainer store in Greensboro explained, because in the eyes of potential thieves, “self-service meant ‘take one for free.’” Kenny Mann remembers how upon entering Snoopy’s, customers could try their luck by buying sealed, brown bags of three records for a dollar. Of course, music played continuously inside these stores.14

Since most of these stores were located in downtown commercial districts or black neighborhoods, young black consumers, many of whom had little or no access to private automobiles, could easily reach them by foot or public transportation. In an age when shopping centers, discount stores, and supermarkets began to proliferate, self-service was quickly becoming the norm for American consumers and interactions with sales staff were becoming scarcer. Owners and sales clerks at black-owned record stores, however, were often on familiar terms with many of their customers and provided them with a friendly and sociable atmosphere that was hard to find at larger merchandisers. In a slim motivational pamphlet from 1967 titled How Poor People Can Increase Their Income, Curt Moore, the owner of Curt’s, outlined his philosophy of customer service and salesmanship and offered aspiring entrepreneurs the following advice: “Regardless [of] what you are selling, you must first sell yourself . . . You must make people like you and not just tolerate you.” As Moore explained years later in an interview, “We would put up with people a lot.” Even when customers came in “popping their fingers [at us], we would still be nice to them. Customer service was very important, and we trained employees to be very nice and thankful to customers.”15

Young black consumers commonly found the owners and clerks in these stores warm and welcoming—but also responsible and community-minded. Store-owners often served as role models for their young customers, and seemed hipper than other adults who held leadership roles within their communities, such as teachers or ministers. Record selling certainly had its glamorous moments; retailers could regale younger customers with stories of nightlife and even rubbing elbows with famous musicians and celebrities. Many retailers attended conventions for black music trade groups such as the National Association of Television and Radio Announcers, where they partied with celebrities like James Brown, Muhammad Ali, and Rudy Ray Moore. Even the most successful black artists, like the Jackson Five, made in-store visits to small, independent retailers, usually to promote a local show that night. Many record retailers were inveterate entrepreneurs who ran a range of businesses, including nightclubs, recording labels, and entertainment management and promotion companies. George Bishop in Greensboro and David Lee in Shelby were themselves musicians and producers who used their record stores to sell their own music. Daniel Adams used his record store in Goldsboro to launch a profitable wholesale business, Tra-Tex, which stocked record retailers with music, jewelry, and smoking accessories. Adams eventually built and operated a factory in Goldsboro to produce his own line of incense, Sugar Babe, which he distributed nationally in the second half of the 1970s.16

Fred Waddell describes the record sellers in Wilmington in these years as “the happy-go-luckiest folk you wanted to meet—never a dull moment. You had to have that kind of personality to sell your product.” Calvin Wade, who as a teenager frequently visited Rozena, Bill Hester’s store in Mebane, and even did odd jobs for him, considered the record dealer a “mentor.” Hester stood out as a successful businessperson who periodically helped members of his community who were in crisis, such as a family whose home was destroyed in a fire. The staff at Snoopy’s was “like your mom and dad,” Kenny Mann explains. “You couldn’t come in there and be disrespectful . . . They were very disciplined.” More than anything, young black customers received attention from black record sellers when they visited their stores. Howard Burchette, host of wncu’s the Funk Show in Durham, North Carolina, recalls how much he interacted with clerks in black-owned record stores, even when perusing album covers for half an hour or more without making a purchase. At white-owned chain record stores, by contrast, Burchette recalls how some clerks “would ignore you—they didn’t give a crap.” Black record-store owners welcomed young black customers into their stores, set examples as self-sufficient entrepreneurs, and enforced a high standard of personal behavior in their shops—in turn offering young African Americans a modest dose of guidance and inspiration.17

Indeed, this was a culture of consumption in which young African Americans, many of them with little money, received respect and felt a sense of belonging that many white businesses in the South still did not offer in the 1960s and 1970s. Anecdotes and empirical research reveal that years of demeaning shopping experiences with discriminatory retailers motivated African American consumers to place a higher value on shopping with familiar and personable merchants than their white counterparts did. Burchette, although he did shop at white chains, recalls avoiding white-owned mom-and-pop record stores in Raleigh in the 1970s, because “being a teenager and black, people in those stores would watch me and make me uncomfortable . . . [as though] I was going to steal stuff.” Claude Barnes remembers that until the very end of the 1960s black shoppers felt fully accepted in only a handful of white-owned stores in Greensboro, and certainly not in the town’s major chain retailers like Kress and Woolworth’s. Black-owned record stores welcomed even the most cash-strapped teenagers, many of whom devised creative ways to consume music. Calvin Wade remembers how his five sisters often pooled their funds together on trips to Rozena to purchase a single 45 record. “We only had one stereo, so everyone listened to the same music,” Wade explains. Even customers without money were welcome to read and examine album covers and liner notes, admire photographs taken of performers with the store’s owners, ask clerks for their opinions on the newest hits, chat with other patrons and, of course, listen to records in the store and even make song requests—with little pressure to purchase.18

For all that they could offer their customers, many black-owned record shops still faced significant challenges in providing them an extensive selection of competitively priced music. These shops frequently suffered from insufficient credit, and they often had to buy stock with cash. As small retailers, black-owned record stores also tended to pay higher rents per square foot than larger record stores did. Economies of scale and better access to credit allowed white-owned record stores, especially chains, to offer consumers lower prices than black record stores could. Disruptions in the supply chain also plagued black-owned record stores and their customers. Despite their expertise in music, many black record dealers, as Moore recalls, “could hear a hit record [on the radio] and not know where to get it” for days, even weeks. Distributors and record labels frequently neglected black record stores and radio stations in smaller southern markets, leading some stores to publish notices in trade magazines desperately pleading for major labels to supply them with their products.19

By the late 1970s and the 1980s, black-owned record stores came to confront even greater obstacles to their financial survival. For years, many white-owned chain record stores remained unconvinced that black music consumers would create profits for them, so they usually opened stores in suburban locations, often in shopping malls or other areas that were overwhelmingly white and often inaccessible to the high proportion of young African Americans who did not have their own cars. By the 1980s, however, record store chains, as well as general merchandisers like Kmart, virtually all of which were white-owned, had greatly increased their share of the southern music market to the point that many black-owned record stores began to suffer. Harry Bergman’s Durham-based Record Bar chain, at one point the nation’s fourth largest seller of records, more than tripled its locations in North Carolina between the early 1970s and the mid-1980s, for example. More and more, white-owned chains stocked the music by black performers that many white retailers had long ignored. Record-store chains’ growing determination to attract black customers certainly helped to drive many black music retailers out of business in the 1980s.20

Home recordings of music posed another threat to black-owned record stores in the 1980s. With cassette recorders becoming more and more popular, many consumers bought their own cassettes, for about a dollar apiece, onto which they could record an album’s worth of songs from the radio or a friend’s collection. Curt Moore first noticed a rise in home recording around 1980. “You could feel it,” said Moore. “That was the first sign of business not being so good.” Moore’s steady stream of customers gradually slowed in the ’80s, and by decade’s end, Curt’s had closed its doors for good. Of the stores mentioned in this article, only Washington Sound in Shelby survived the 1980s, and it declined significantly in the first half of the 1990s, until closing by the middle of the decade. Chain stores, with their larger profit margins, could much more easily withstand the loss of revenue resulting from home recording than could independently owned stores. In retrospect, the 1980s may well have marked the twilight years of the golden age of African American-owned record stores.21

In the 1990s and the 2000s, transformations in both music retail and the African American business landscape dramatically diminished the influence of black-owned record stores in their communities. Hip hop, the most prominent and influential of African American popular cultures in recent years, has elevated the status of music-related businesses—including record labels, production companies, and clothing lines—while bringing little attention to black-owned record stores. Media reports on the rise of so-called “hiphopreneurs” rightly focus on the most spectacular success stories of entrepreneurs like Shawn “Jay-Z” Carter, Sean Combs, Russell Simmons, and Percy “Master P” Miller. Nonetheless, the rags-to-riches tales of hip-hop entrepreneurs have largely ignored and devalued black-owned record stores’ more modest visions of the music business. Typical of such conceptions of African American businesses can be found, for example, in a 2002 cover story by the magazine Black Enterprise on “the hip hop economy.” While the author maintains that “every hip hop CD sold, every dollar made from urban gear, every buck generated from television shows, radio programs, films, and even video games with a bit of ‘flava’ contribute to this $5 billion burgeoning sector,” not once does he mention record stores. This lack of recognition marked an ironic, even sad, turn of events for black music retailers. Not only did many black independent shops sell hip hop long before major labels or chain retailers showed the genre much attention, but over the years black music retailers also founded a number of seminal independent hip hop labels, including Bobby Robinson’s Enjoy Records, Paul Winley’s eponymous label, and Master P’s No Limit Records.22

The scant mention of record shops amid the media coverage of hip-hop businesses also reflected a broader decline in African American retail in the 1990s and 2000s. In strict numerical terms, black retail businesses continued to grow in the 1990s and 2000s, yet their growth was miniscule compared to that of non-retail black businesses. Proportionally speaking, fewer and fewer African American entrepreneurs chose to open retail operations in this period. As late as 1969, retail businesses comprised nearly 30 percent of all African American firms, yet by 2002 they represented fewer than 9 percent of all black businesses. From the 1970s onward, as blacks’ access to corporate employment increased and their opportunities for franchising with national chains improved, independent retail began to lose its luster for many African Americans. The exodus of much of the middle class from traditionally black neighborhoods since the 1970s also contributed to the decline of black commercial districts. Unfortunately, even African American consumers’ own support for black-owned businesses appears to have shrunk by the 1980s. In a 1984 survey, just over 38 percent of African American seventeen- to twenty-four-year olds affirmed that “blacks should shop whenever possible in black stores,” down from 70 percent of black respondents who had voiced the same sentiment in a 1968 survey. In 1991 the NAACP reported glumly on “the dying breed” of “black mom-and-pop-retailers” in its newspaper The Crisis: “Empty storefronts in black areas all across the country testify that there are probably fewer stores within the black community today than 30 years ago, and fewer still with black owners.”23

For some African Americans who can remember black business districts when they thrived, their decline serves as a symbol of a perceived downturn in black communities more generally since the 1960s. In interviews collected by the Southern Oral History Program for the project “Remembering Black Main Streets,” black southerners born before the 1950s express deep regret over the loss of black business districts, even while acknowledging that they had arisen out of the racist logic of segregation. Claude Barnes laments the “lost entrepreneurship” of East Market Street in Greensboro, which once provided the city’s African Americans with a means of “surviv[ing] a period of segregation.” Meanwhile, Leroy Beavers, a barber from Savannah, Georgia, views the exodus of black shoppers to white-owned stores and a local shopping mall as the culprits for a sharp decline in his city’s black business district on West Broad Street. Taken together, these changes, Beavers charges, amounted to a “genocide of a social life where people had just pure respect for each other.”24

Generally speaking, the last decade has been unkind to music retailers of all kinds, but especially the independents, which include the vast majority of black-owned stores. Double-digit declines in music sales almost every year of the 2000s prompted Billboard in 2009 to warn of prolonged “darkness before dawn,” when “the harrowing downturn in sales that started in 2001” might finally stop. Of course, free downloads pose a huge challenge to brick-and-mortar retailers who sell their music legally, but even legal downloads from online sellers tend to be priced at least twenty percent less than those found in most independent shops. Big box stores like Best Buy and Walmart have also made deep inroads into music retailing and have further reduced the independents’ market share. Some products, like singles, which comprised a significant portion of many black record stores’ sales in the 1960s and 1970s, are now available usually only as downloads. Of course, some black-owned independent record stores are still in business, but they are an aging and very endangered species. Often, the owners and the customers are well over fifty. Many older customers have yet to master downloading music, if they even have an Internet connection in their homes. Meanwhile, many older record dealers stay in business as long as they can, until bad health, rising rents, or their dramatically shrinking customer base force them to close; in some rare cases a younger family member may take over the business. Even 125th Street in Harlem, which was home to six record stores in 1970, saw its two most prominent black-owned music retailers close for good in 2008.25

Curiously, stores that specialize in selling vinyl stand out as one of the few groups of music retailers that have shown healthy growth in the last decade. Such operations bear some resemblance to black-owned record stores of the 1960s and 1970s, insofar that they are often small, independent operations that double as meeting spots and public spaces for the customers they serve. In other regards, however, current vinyl specialists are quite different from their independent, and especially black-owned, predecessors. Anecdotal evidence, especially as seen in recent literature that celebrates the revival of independent record stores, suggests that the large majority of the owners and customers at such stores are white as well as male, although the ranks of club and party DJs who buy vinyl do represent a more racially diverse customer base. These days, most record stores can utilize two strategies for survival: by serving as boutiques for the most devoted of music fans or by selling considerable stock online, and often independent stores do both. Furthermore, the new generation of record stores, as well as the few surviving members of the old guard, really survive on the patronage of a small circle of dedicated record collectors, true enthusiasts whose tastes often skew toward the antiquarian and obscure. These are often wonderful stores with impressive stock and dedicated owners, but they are not the most accessible to customers who lack collectors’ sophisticated and developed tastes. Teenagers with just a few dollars in their pockets to spend on music seem much more likely to purchase online, rather than in a store—if they even pay for their music, that is.26

Interestingly, the findings in this article suggest a significant discrepancy between young African Americans who lent their support to black-owned businesses in the 1960s and 1970s and the many white, and often affluent, Baby Boomers who voiced sharp objections to American capitalism in the same years. Contemporary opinion surveys of college students, most of them white and with full access to American consumer culture, revealed a deep skepticism of business and consumption; standard studies of the era also show how hippies often “scorned materialism and consumption.” Boomers embraced the counterculture, and especially rock music, for providing an alternative to America’s dominant consumer culture, not for collaborating with it. Many young white Americans held favorable opinions of non-traditional businesses founded by young hippies, but few in the counterculture viewed more traditional, middle-aged independent businesspeople as allies—and even hip businesses were not spared rebuke entirely in countercultural circles. Underground newspapers like San Francisco’s Good Times, for example, excoriated so-called “hip capitalists” for fueling an “age of acquireous.”27

Many young African Americans in these years, by contrast, envisioned themselves not as culturally opposed to entrepreneurs, but as members of a common community who could forge close relationships around music and business. In the 1960s and 1970s these businesses provided African Americans—even young ones with little money—black-oriented, safe spaces in which they could congregate, shop, and hang out without worrying about how whites might judge them. Despite a larger trend in American retail toward chains and national mass merchandisers that was already underway by the 1960s, black record stores thrived as some of the most accessible areas in the American marketplace for black consumers, especially young ones. Unfortunately, black-owned music retailers—at least as brick-and-mortar storefronts—will probably never rebound to the levels of prominence and relevance that they once enjoyed. But at their zenith in the 1960s and 1970s, black-owned record stores offered their patrons something truly invaluable—not only access to black music, but to a consumer culture in which African Americans found respect, community, and a vibrant public life.

This article first appeared in volume 17, no. 4 (Winter 2011).

Joshua Clark Davis is an assistant professor in the Division of Legal, Ethical, and Historical Studies at the University of Baltimore. He is the author of From Head Shops to Whole Foods: The Rise and Fall of Activist Entrepreneurs (Columbia University Press, 2017), and co-directs “Media and the Movement,” a NEH-funded oral history and radio digitization project based at UNC on activists of the Civil Rights and Black Power era who worked in media.

Header image by Pete Bakke, October 24, 2009, courtesy of Flikr.com, CC BY 2.0.