“This was an anxious time for American Jews, stung by the anti-Semitic quotas and discrimination of the interwar years and the growing horror regarding the fate of European Jewry as the Holocaust came to light in the 1940s.”

My first experience at a southern Jewish summer camp was not easy. I felt out of place. I couldn’t speak Hebrew. I didn’t know the songs, nor could I join in the raucous chanting of the Birkat Hamazon, the traditional Jewish blessing after meals. I was homesick. I didn’t want to spend the night at camp. I hated corndogs. And to make matters worse, I was in my mid-thirties, and it was hot as blazes in south central Mississippi. As the Project Director of the Museum of the Southern Jewish Experience, located at Camp Henry S. Jacobs in Utica, Mississippi, in the early 1990s, I wondered what sane person attends summer camp in Mississippi, let alone Jewish summer camp?

I was homesick. I didn’t want to spend the night at camp. I hated corndogs.

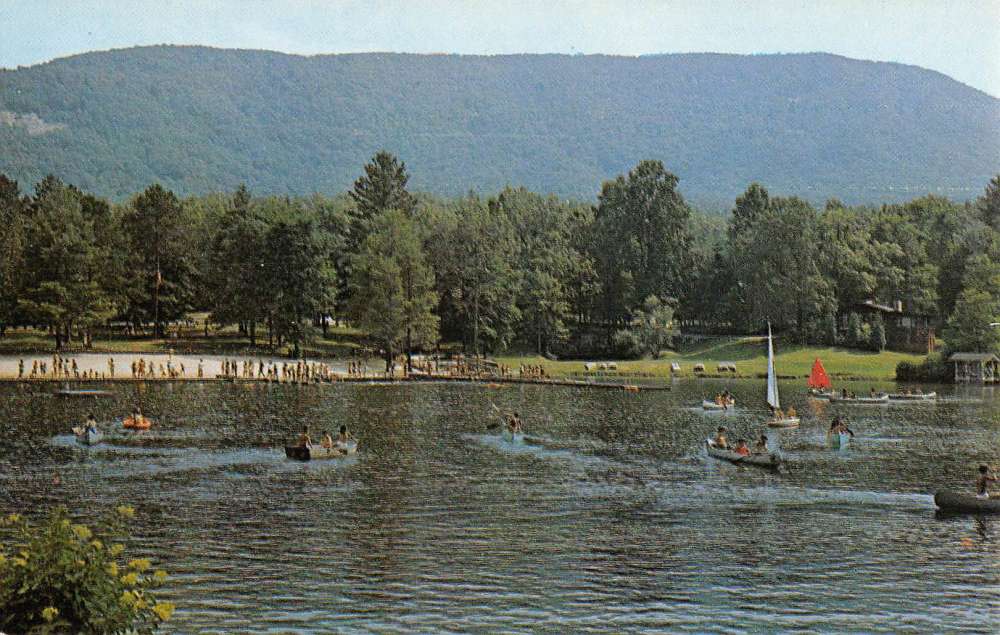

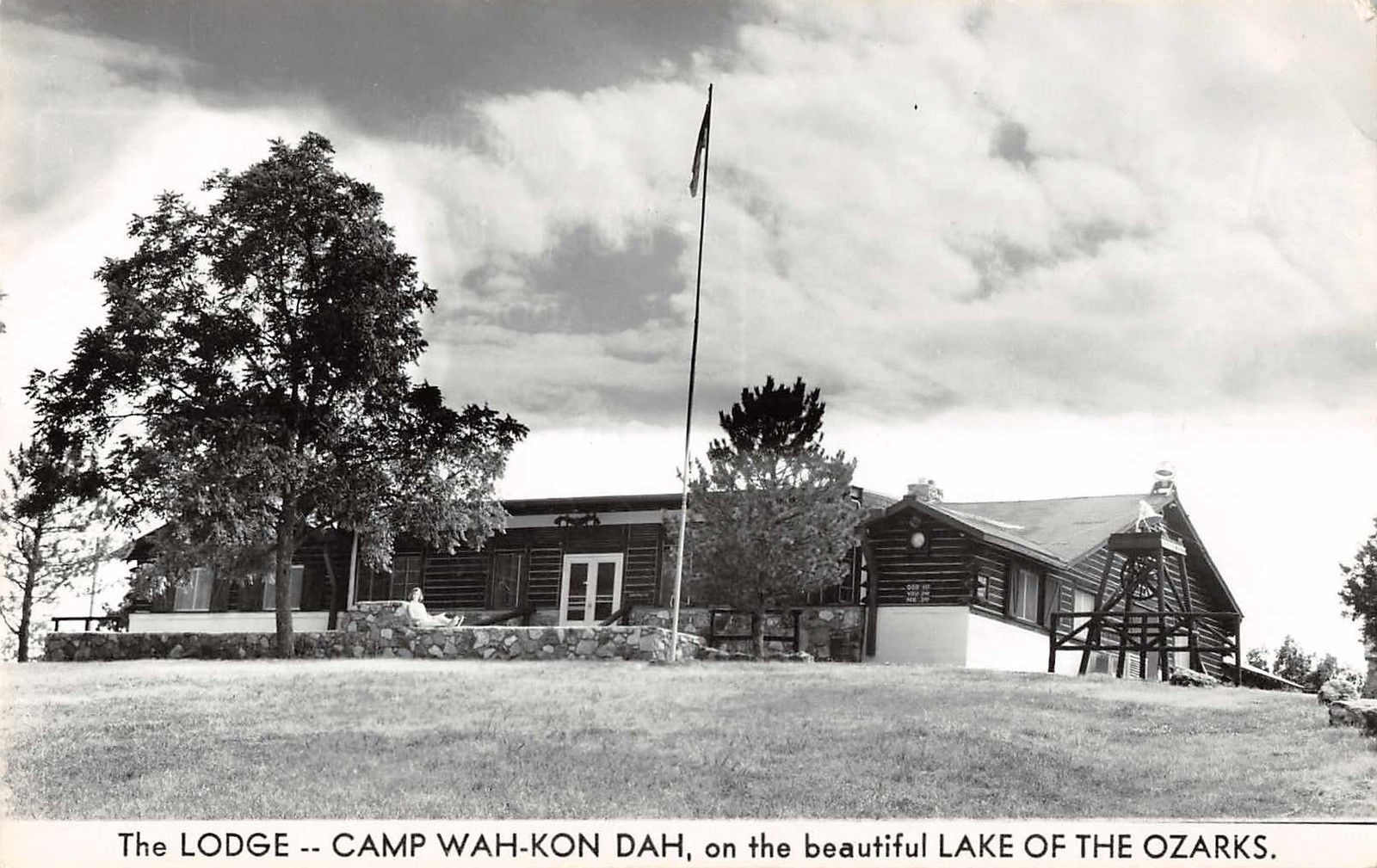

My own childhood camping experience began in the late 1960s at Camp Wah-Kon-Dah in Rocky Mount, Missouri, on the Lake of the Ozarks—a camp for Jewish youth, but not a Jewish Camp. Camp Wah-Kon-Dah was “quietly Jewish.” Since many of the campers came from small southern towns with tiny Jewish populations, it was a new and exciting experience to be among other Jews. But imagine a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy regarding our Jewish identity—two hundred Jewish kids boating, swimming, and shooting archery, but nobody talked about our “Jewishness.” It could have been a covert operation with the Jewishness so quiet. We knew we were Jewish, enough said. To an unsuspecting visitor, Wah-Kon-Dah looked and sounded like any other American summer camp—except for all the Jewish campers.

And that was exactly what Ben Kessler, the founder of Wah-Kon-Dah, wanted when he opened a private Jewish summer camp for boys in 1939. A Jewish native of St. Louis, Ben Kessler began Camp Wah-Kon-Dah in an era of wartime fear and disruption. This was an anxious time for American Jews, stung by the anti-Semitic quotas and discrimination of the interwar years and the growing horror regarding the fate of European Jewry as the Holocaust came to light in the 1940s. Kessler hoped to give his campers a summer filled with joy, the opportunity to build strong physiques, improve personal character, learn skills, and, lastly, to “model a democracy” as a camp community.1

Wah-Kon-Dah was part of a summer camp craze in America that was shaped by the “cult of the strenuous life” (an anti-modernist ideology that sought to repair and strengthen American society through contact with the “great outdoors”), social reform movements of the Progressive Era, and “back-to-nature” work projects of the New Deal. Historian Gary Zola describes Jewish camping as a “genuine hybrid of organized camping in America.” The first Jewish summer camps were established in the early 1900s to serve both as a pastoral refuge for needy Jewish children in the urban Northeast and as sites of Americanization for children of recent Jewish immigrants. During the 1930s, Jewish summer camps and retreat centers with political agendas sponsored by communist, socialist, Zionist, and Yiddish organizations grew in popularity. The majority of these institutions were located near the large Jewish population centers along the East Coast. A smaller, but important, number of Jewish boarding houses, camps, and kosher inns were located in the southern mountains, including Wildacres, the summer location of the North Carolina B’nai B’rith Institute.2

Non-denominational, private Jewish camps grew during the prosperous years after World War II and today dominate Jewish camping, including the ten Jewish summer camps located in the American South. For the mid-South, Camp Wah-Kon-Dah in Rocky Mount, Missouri, represented a different model of private Jewish camping guided by religious pluralism rather than a specific political or denominational expression of Judaism. At Wah-Kon-Dah, the owner and campers were Jewish, but there was little or no explicit Jewish programming or education. Jonathan Sarna connects this model to an earlier era of Jewish camping, in which Jews emphasized American values and “Judaism was reduced to a whisper.” But concerned parents clearly perceived Wah-Kon-Dah as Jewish; attending private summer camp was both a significant rite of passage and a symbol of affluence for southern Jewish youth. Demographic and religious challenges faced by the southern Jewish community—a small population, particularly in rural areas, surrounded by a powerful, evangelical Christian tradition—had existed since the Colonial era. Each generation of southern Jews confronted this cultural negotiation through assimilation, intermarriage, adoption of local racial codes and institutions, including slavery and segregation, and a range of activism during the Civil Rights Movement from “quiet” resistance to public protest.3

Private, for-profit camps like Wah-Kon-Dah, and a similar camp, Kawaga, founded by Rabbi Bernard Ehrenrich of Reform congregation Temple Beth Or in Montgomery, Alabama, drew the children of upper middle-class and well-to-do Jewish families. Like Ben Kessler of Wah-Kon-Dah, Ehrenrich longed to create a summer camp where Jewish children could improve mind, body, and spirit. Escaping the heat of Alabama each summer for Maine, and later Wisconsin, Ehrenrich found an appropriate site for Kawaga in 1916 in Minocqua, Wisconsin. Rabbi ‘Doc E” Ehrenreich expressed his camping philosophy in a favorite saying, “Take the ‘G’ from GREAT, the ‘O’ from OUT, and the ‘D’ from DOORS and the GREAT OUT DOORS can be translated into the name of GOD.”4

Take the ‘G’ from GREAT, the ‘O’ from OUT, and the ‘D’ from DOORS and the GREAT OUT DOORS can be translated into the name of GOD.

Jewish education, including programs that explored American Jewish history and identity, often received short shrift in urban and rural congregations, due to a lack of infrastructure, institutional resources, and the small number of Jewish families. From the 1940s to the 1970s, a new grassroots activism reinforced American Jewish communities, including those in the Jewish South, through regional summer camps and year-round adult education. As a ‘cultural island” in an isolated setting, separated from home and parents, summer camp was the perfect setting for a total immersion in southern-style Judaism. The combination of education, food, religious instruction, music, physical activity, spirituality, and Jewish tradition brought campers back year after year to experience the camp’s temporary, but powerful, recurring community.5

Jewish youth, staff, and parents alike experienced a profound sense of belonging at Jewish camps across the South, whether for two weeks or two months. There was a palpable feeling of family and solidarity—even at Wah-Kon-Dah with its Jewishness a mere hum. We shared a cultural language of Jewish foods, jokes, melodies, language, the Jewish organizations our parents belonged to, the ritual life cycles of Jewish life, and, most importantly, the unspoken rules of how to be Jewish but still fit into white southern society. The challenges of camping and the embrace of a Jewish world changed our lives. We were expected to thrive, and for the most part, we did. Raising a ‘southern Jewish consciousness” among campers had long-term consequences, too. An intricate network of southern Jewish relationships created in the summer influenced college decisions, future careers, religious involvement, romance, and the next generation of Jewish youth. Many campers and counselors grew into future leaders of the Jewish South’s local and regional organizations, historical societies, museums, programs for youth, and synagogues. Campers took their summer experiences of Jewishness back home and revitalized the Jewish worlds from which they came.

Promoting Jewish education, community, cultural life, and most importantly, continuity—raising Jewish children committed to their faith and its long-term survival—was the lifework of southern Jewish camp directors, such as the Popkin brothers at Camp Blue Star in Hendersonville, North Carolina (est. 1948), and Macy Hart at Camp Henry S. Jacobs in Utica, Mississippi (est. 1970), a project affiliated with the Reform Movement in Judaism. During a regional fundraising campaign to secure property for Camp Henry S. Jacobs in the 1960s, the project was touted as ‘The Key to a Living Judaism” and promised to send forth ‘young Jews proud of their faith and heritage, ready to go to college as committed Jewish Youth.”6

The concept of a vital “living” Judaism remains at the philosophical core of southern Jewish camps today. Camp Blue Star’s contemporary “Living Judaism” program “integrates Jewish values, culture, and traditions” that “teach as well as uplift.” Miles Kuttler, a former staff member at Blue Star, explains: “You’d see one thousand Jewish kids in the hills of North Carolina singing Hebrew songs.” With emotion in his voice, Kutler concludes, “There’s no way to describe it.” Southern Jewish denominational camps with similar educational missions include Camp Judaea, Hendersonville, North Carolina (est. 1960), a program of Hadassah, the Women’s Zionist Organization of America, and Camp Ramah Darom (Ramah of the South) in north Georgia (est. 1997), affiliated with the Conservative Movement in Judaism. Camp Ramah Darom has a Center for Southern Jewry that provides adult and family programs throughout the year for local Jewish families. Camp Darom in Wildersville, Tennessee, is a modern Orthodox Zionist camp supported by the Baron Hirsch Congregation in Memphis and described as “the only Orthodox sleep away camp in the entire south.”7

Camp Blue Star, the “oldest, family-owned, private, kosher Jewish camp in the southern United States,” was founded in 1948 on 740 acres in the mountains of western North Carolina, the same year as the founding of the state of Israel. Sarna describes this era as a “crucial decade in Jewish camping,” in which Jewish education was both an expression of “cultural resistance” after the Holocaust and an American promise to build and uphold the Jewish people. Brothers Herman, Harry, and Ben Popkin were leaders in Atlanta-based Zionist and B’nai B’rith youth organizations who hoped to build a private Jewish summer camp in the South when they returned from service in World War II. While conducting research for their business venture, Herman and Ben Popkin consulted with owners of non-Jewish camps in north Georgia. Jane McConnell of Camp Cherokee was “honest and straightforward” and gave the Popkins this advice: “You boys ought to do it. There’s a need for a camp like the one you propose, especially for older children. Most private camps down south won’t accept Jewish children, and those that do, do so on a strict quota basis.” As historian Eli Evans, a former Blue Star camper, described in The Provincials, his classic memoir of the Jewish South, “Herman and Harry Popkin . . . built a veritable camping empire in the postwar era.” It was a southern Jewish mountain paradise for young boys like Evans—a magical world of bonfires, hiking, Israeli folk dancing taught by actual Israelis, Jewish girls, and deep discussions about God and Jewish identity. “For the rest of our days, it seemed,” wrote Evans, “one sure way that Jewish kids all over the South could start a long conversation was by asking, ‘What years were you at Blue Star?’”8

One sure way that Jewish kids all over the South could start a long conversation was by asking, ‘What years were you at Blue Star?’

Although their Jewish educational methodologies differed—Camp Blue Star’s commitment to Jewish education was front and center in their daily programming, while Camp Wah-Kon-Dah’s Jewish ideology was expressed in “values,” rather than overt curriculum—the two camps are joined by their founders’ commitment to providing the highest quality, private camping experience for Jewish children. Wah-Kon-Dah’s founder, Ben Kessler—”Uncle Benny” to his campers—was born in 1903. He came from a family of ten that included his four brothers and three sisters. His eastern European parents, Jenny and Jacob Kessler, worked in the fruit and produce business in St. Louis, where they lived in the working-class neighborhood of Kerry Patch, named for the many Irish-Catholic families who lived there. According to their nephew, Thom Lobe, the Kessler brothers were “all big guys” and fine athletes. They were award-winning boxers and football players in high school. Ben Kessler refereed fights, including one with boxer Rocky Graziano, and Ben’s brother Harry Kessler, known as “the millionaire referee,” worked in the ring with boxing champions Joe Louis, Jack Dempsey, and Muhammad Ali. With his passion for athletics, coaching, and community recreation, camping was a natural profession for Ben Kessler. His first boys’ camp in Brumley, Missouri, closed when Kessler joined the armed forces during World War II. In 1945, he re-opened the camp on a spacious peninsula on the Lake of the Ozarks, a lake created in the early 1930s with the construction of Bagnell Dam on the Osage River. The dam provided electric power for the region and, equally important, thousands of jobs soon after the Depression began.9

The name Ben Kessler chose for his camp, Wah-Kon-Dah, referred to ‘the Great Spirit” of the Omaha tribes. Why did a nice Jewish man like Ben Kessler choose an Indian name for his camp? Early leaders in Jewish camping adopted the same American Indian folklore and heritage that so deeply influenced American camping at the turn of the twentieth century. Folklorist Rayna Green argues, “One of the oldest and most pervasive forms of American cultural expression . . . is a ‘performance’ [called] ‘playing Indian.’” It began with Pocahontas saving Captain John Smith, the first Thanksgiving, and Squanto saving the Pilgrims. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Hiawatha (1855) helped to solidify the image of the Indian in the American imagination. Victorian-era societies like the Elks, the Lions, and the Kiwanis introduced the idea of “playing Indian” to the white middle-class by embracing nomenclature that suggested the power of the natural world. Pseudo-Indian language like “Kiwanis” reinforced Native American values. For the Boy Scouts, founded in 1908, Indians represented the scouting ideal of manly independence. These themes were perpetuated in summer camps, and Jewish camps, too, embraced this celebration of Native American culture, frequently adopting the names of local Indian tribes for their institutions or using initials or even a Hebrew word to create an Indian-sounding name with a Jewish backstory. (Jewish comedians have speculated whether Native Americans might give Jewish names like “Camp Whitefish” and “Camp Kreplach” to their summer camps.)10

There were weekly boxing matches at Camp Wah-Kon-Dah, and the champions were revered figures at camp. If you didn’t box, you played tennis, waterskied, were an expert marksman, or an intrepid canoer. Sportsmanship and athleticism were especially celebrated during the last week of camp, when color wars, a world of red and black, divided the camp into two teams who fought to win endless baseball games, swimming competitions, and one-legged sack races across the athletic field. Ben Kessler was in the business of building strong Jewish youth. When camp ended after eight weeks, we were sturdy pioneers, but not the kibbutz kind of pioneer. At Wah-Kon-Dah our focus was less on Israel and more on the American frontier.

Ben Kessler, a product of World War II, a child of immigrant parents, a witness to the tragic losses of the Holocaust, created a summer world where Jewish children learned confidence, team work, respect for God, and how to throw a good punch. No one ever forgot Ben Kessler’s motto that hung from a cross beam in the dining lodge: “God first—you second—me third.” Wendy Mogel, author of The Blessing of a Skinned Knee: Using Jewish Teachings to Raise Self-Reliant Children, would have loved Uncle Benny. Mogel remembers the summer she broke her leg at camp while riding bareback “as my best summer in 16 years of camp,” because she learned so much about herself. Kessler was all about fending for oneself, or as Mogel describes it, “controlled doses of risk,” which campers experienced by the boatload at Wah-Kon-Dah while learning to water ski (I was terrified), perform in talent shows (terrifed, again), or ask a boy to dance on Sadie Hawkins Day (no way).11

There were no Friday evening Sabbath services at Wah-Kon-Dah. Instead, we gathered at “Inspiration Point” each Sunday morning, everyone dressed in starched “whites” for a sermon from Uncle Benny, who was a master storyteller. He wove Indian tales with lessons about team spirit, loyalty, kindness, and respect for nature. I vividly remember his story about the power of community and family. Uncle Benny found a small stick on the ground and easily broke it in two. He then took the broken pieces, added a few more, and, holding all those together, tried unsuccessfully to break them. We got the message.

Sunday services were followed by a noontime meal of southern fried chicken, mashed potatoes, peas, and red Jello. George Buckner, an African American chef, ran the kitchen at Wah-Kon-Dah for over thirty years. Hiring African Americans, like Buckner, to manage dining facilities because of their historical “talent” in food service was a common practice at white-only camps and synagogues that began in the late nineteenth century and continued well into the late twentieth century. Buckner and his family rose every day at five a.m. to prepare breakfast for the camp. If you had a birthday during the summer, Mr. Buckner baked you a cake. The entire camp sang “Happy Birthday” just for you. If you caught a fish in the lake, he fried it for your cabin. On Thursday nights, Mr. Buckner prepared delicious barbecue ribs, which were served outside with fresh watermelon for dessert. Uncle Benny taught campers how to cut the watermelon to fit in the palm of your hand, so you could swipe it across your counselors’ faces.12

Many of the counselors and staff at Wah-Kon-Dah were not Jewish. Kessler hired talented young men and women from colleges and universities across the nation. He emphasized excellence, and several of his administrative staff, like “Wild Bill” Heyde, worked as St. Louis-area school principals and teachers during the winter months. They were larger-than-life figures that we adored, and hoped we might be like some day. Campers came from Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, Kansas City, Little Rock, Memphis, Oklahoma City, Omaha, St. Louis, Tulsa, and small towns throughout the South. Stephen Rich remembers how he took the overnight train from Atlanta to St. Louis with his Jewish buddies and their excitement about staying in sleeping compartments.

Kessler spent the winter months visiting cities like Atlanta, where he recruited campers. But word of mouth did most of the work, because Wah-Kon-Dah’s reputation was its best marketing device. Once you arrived at camp, Kessler greeted every camper with a hug and a quick verbal I.D., “Hello, Marcie Cohen of 440 Rosemary Lane, Blytheville, Arkansas!” It was reassuring to know that the camp director knew exactly where you came from and who your people were. This mental exercise was a dazzling demonstration of a camp director’s knowledge of southern Jewish geography.

The days and weeks at Wah-Kon-Dah were filled with non-stop summer rituals, traditions, song sessions, and wildly creative programs devised by Kessler and his staff. Monday night was square dancing. Wednesday night was a special event. Thursday night was “Cabin Night.” Saturday night was a boy-girl social preceded by “Lovely Ladies Day,” a few hours devoted to hair-dos and wardrobe. Sunday was reserved for non-sectarian morning services and weekly ‘Council Fire Awards.” Once a summer, “King Neptune” arrived. We gathered at the waterfront with our counselors, the night eerily lit by lanterns. Just as we were getting sleepy, a fire-breathing dragon roared onto the beach, and a counselor dressed as an impressive, seaweed-covered, trident-carrying Neptune rose out of “the icy depths” of the lake and terrified campers by pouring ice water and ice cubes down our backs.13

The most dramatic moment of the summer was Tomahawk Night. (What good Jewish camp doesn’t have a Tomahawk Night?) In the middle of the night, campers were awakened and led to the ball field by counselors in politically incorrect Indian garb, carrying lit torches. We stood in a large circle as the “Indians” chose senior campers judged to be the “most outstanding” and pushed them into the center of our gathering. After being inducted into the Tomahawk Club in a secret ceremony, the special campers slept on the ball field overnight and were not allowed to speak to anyone for twenty-four hours. Each received a sacred tomahawk. In the morning, the Tomahawk Club recipients were announced to the entire camp. It was high drama imbued with a sacred sense of honor I have not felt since those days.

Camp Wah-Kon-Dah closed in 1969. There was a terrible car accident in which a camper, Marcy Wexner, died. It was the first fatality in the camp’s history, and it devastated Ben Kessler and the camp community. Her death felt like the end of our innocence, and I guess it was. That was the same summer as Woodstock. “Aquarius” won a Grammy for record of the year, Neil Armstrong stepped on to the moon, college students took over the administration building at Harvard, and the American death toll in Vietnam rose to over 40,000. The recession of the 1970s, coupled with rising taxes, expenses, increased accreditation, and regulatory procedures, challenged private camp owners like Ben Kessler, especially when insurance rates escalated because of a camper-related accident.14

The Jewish Community Center of St. Louis acquired Wah-Kon-Dah in 1969 after a group of Jewish benefactors purchased the facility, re-named it Camp Sabra, and donated the camp to their community in 1970. My sister and I returned for Sabra’s charter year and found it a surreal experience. The Camp looked the same, but something was terribly awry. Uncle Benny was gone. The counselors in crisp, white shorts were no more. My friends had vanished to camps in Minnesota and Wisconsin. My sister Jamie went on a week-long canoe trip where the counselors in charge lost a few campers, to my parents’ horror. They were found after a day or two. And most strange of all, the camp was suddenly Jewish. Cabin names changed from Osage and Kickapoo to Habonim and Golan. Israeli youth led dance workshops and song sessions. Shabbat replaced Sunday. And there were no more lunchtime pizza burgers—a startling introduction to the kosher dietary laws in which meat and milk never came together on a bun. We enjoyed our summer at Sabra, but eventually my sister and I followed our Wah-Kon-Dah friends to Camp Thunderbird, another “quietly Jewish” camp in Bemidji, Minnesota, with the familiar mix of Jewish campers, Native American culture, and challenging programming we had known at Wah-Kon-Dah.15

There were no more lunchtime pizza burgers—a startling introduction to the kosher dietary laws in which meat and milk never came together on a bun.

I interviewed many Camp Wah-Kon-Dah alumni, and each described their camping experience as “life changing.” These campers were part of a generation of young American Jews who were “transformed,” as Jonathan Sarna explains, by the “spell of these camps,” and from these campers came future Jewish community leaders committed to philanthropy and building American Jewish life. Kessler and the staff at Wah-Kon-Dah created this transformational educational experience every summer for over twenty years. Mike Kessler, son of Ben Kessler’s brother Saul, was both a camper and counselor for many years and said of his Uncle Ben, “There was no way if you were involved with Ben, not to see his heart for young people. Uncle Ben was a righteous guy—there was a way to get things done and that was the righteous way. He taught what it meant to live an honorable life.”16

Merrill Bauman Stern of Little Rock, Arkansas, said of Wah-Kon-Dah, “I felt like I had come home.” It did feel like home, more than home did sometimes. Without explicit Jewishness at Wah-Kon-Dah, its quiet Jewishness created a place where we could be Jewish southerners for once and not feel like outsiders. Finally “insiders,” we were members of a magical world that was impossible to describe to my non-Jewish friends back home. My mother warned, “Don’t go on and on about camp—it’s not polite to brag.” So, I didn’t.17

Camp ended. Our trunks were put away in the attic until the next summer. Jamie and I were back home, and again we became “the Cohen girls.”

This article first appeared the Spring 2012 Issue (vol. 18, no. 1).

Marcie Cohen Ferris is a Faculty Editor of Southern Cultures. She is the author of The Edible South: The Power of Food and the Making of an American Region and Matzoh Ball Gumbo: Culinary Tales of the Jewish South, and is currently at work on a forthcoming book with UNC Press, Edible North Carolina: A Journey Across a State of Flavor.

- Camp Wah-Kon-Dah was a private boys camp with approximately 125 campers until 1957, when it became co-ed and ultimately served about 200 children each summer. For examples of work that laid the philosophical underpinnings of the American camping movement in the early twentieth century, see Bernard S. Mason, Camping and Education: Camp Problems from the Campers’ Viewpoint (NY: McCall Company, 1930). Mason, a professor in sociology at Ohio State University, was an authority on camping and wilderness education (1920s–1950s), who emphasized building creativity and autonomy in children through activities steeped in American Indian folklore.

- Jonathan D. Sarna, ‘The Crucial Decade in Jewish Camping,” 29–30, and Gary P. Zola, ‘Jewish Camping and Its Relationship to the Organized Camping Movement in America,” 2, in A Place of Our Own: The Rise of Reform Jewish Camping, ed. Michael M. Lorge and Gary P. Zola (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2006); Nancy Mykoff, ‘Summer Camping,” in Jewish Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia, ed. Paula E. Hyman and Deborah Dash Moore (New York: Routledge, 1997), 1359–1364; Amy L. Sales and Leonard Saxe, How Goodly Are Thy Tents: Summer Camps as Jewish Socializing Experiences (University Press of New England, 2004), 142–143; Zola, ‘Jewish Camping,” 19; In the early 1930s, I. D. Blumenthal, a successful Jewish businessman from Charlotte, bought Wildacres from Thomas Dixon, who had purchased the property with film royalties from D. W. Griffith’s controversial Hollywood epic Birth of a Nation (1915), based on Dixon’s novel The Clansman. Dixon invested heavily in the property and, after losing a great deal of money when the stock market crashed in 1929, was forced to sell the 1,400 acres at a much-reduced price. In his essay on the history of American Jewish camping, Jonathan Sarna notes that the availability of affordable land and real estate in this era allowed many Jewish institutions and individuals to purchase land for camps and retreats. Sarna, ‘Crucial Decade in Jewish Camping,” 37; Wildacres Retreat, ‘The History of Wildacres,” http://wildacres.org/about/history.html.

- Sales and Saxe, How Goodly Are Thy Tents, 26; Sarna, ‘Crucial Decade in Jewish Camping,” 30.

- Sarna, ‘Crucial Decade in Jewish Camping,” 28–31; Sales and Saxe, How Goodly Are Thy Tents, 26; Zola, ‘Jewish Camping,” 14; Harold S. Wechsler, ‘Rabbi Bernard C. Ehrenreich: A Northern Progressive Goes South,” in Jews of the South: Selected Essays from the Southern Jewish Historical Society, ed. Samuel Proctor and Louis Schmier with Malcolm Stern (Macon, GA: Mercer Univerity Press, 1984), 62. Ehrenreich’s Camp Kawaga was inspired by Camp Kohut, founded in 1907 by Rabbi Alexander Kohut in Oxford, Maine. Kohut’s successful formula of physical activity and Jewish educational enrichment for children in a beautiful outdoor setting motivated many campers to maintain connections to the American Jewish community throughout their lives; Zola, ‘Jewish Camping,” 14; ‘Camp Kawaga History,” http://www.kawaga.com/about/history/.

- Sales and Saxe, How Goodly Are Thy Tents, 46.

- Stuart Rockoff, ‘Henry S. Jacobs Camp, Utica, Mississippi,” Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities, http://www.isjl.org/history/archive/ms/utica.htm.

- ‘Camp Blue Star,” ‘Southern Jewish Summer Camp: Camps in the Region,” Deep South Jewish Voice, January 2010, 28; Leonard Rogoff, Down Home: Jewish Life in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 280; Jewish summer camps in the South include Camp Barney Medintz, a residential summer camp for the Marcus Jewish Community Center in Atlanta, founded in the 1960s, and located in north GA, Camp Blue Star, Hendersonville, NC (est. 1948), Camp Coleman, a program of the Union of Reform Judaism, Cleveland, GA (est. 1964), Camp Darom, a project of the Baron Hirsch Congregation, Wildersville, TN (est. 1981), Camp Henry S. Jacobs, a program of the Union of Reform Judaism, Utica, MS (est. 1970), Camp Judaea, a program of Hadassah, the Women’s Zionist Organization of America, Hendersonville, NC (est. 1960), Camp Ramah Darom (Ramah of the South), north GA (est. 1997), and Camp Sabra, a project of the St. Louis, Missouri Jewish Community Center, Rocky Mount, Missouri (est. 1970). For a history of Henry S. Jacobs Camp, see Stuart Rockoff’s essay in the online Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities under ‘Utica, Mississippi,” http://www.isjl.org/history/archive/ms/utica.htm; Camp Darom website: http://www.campdarom.com/index.html.

- Lee J. Green, ‘Cold Outside But Time to Plan for Summer Camp,” Deep South Jewish Voice, January 2008, 26. Today, over 750 campers and 300 staff attend Blue Star’s six camps each summer. To read more about Camp Blue Star and other Jewish camps’ influence on southern Jewish life, see Leonard Rogoff’s important history of Jewish life in North Carolina, Down Home: Jewish Life in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 279–281; Sarna, ‘Crucial Decade in Jewish Camping,” 36; Herman M. Popkin, Once Upon a Summer: Blue Star Camps—Fifty Years of Memories (Fort Lauderdale, FL: Venture Press, 1997), 185; Eli N. Evans, The Provincials: A Personal History of Jews in the South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 148, 150.

- Judith Lipsitz Capes telephone interview with Marcie C. Ferris, September 20, 2006; Mike Kessler telephone interview with Marcie C. Ferris, October 2, 2006; Thom Lobe telephone interview with Marcie C. Ferris, September 30, 2006; Stephen Rich telephone interview with Marcie C. Ferris, September 12, 2006; ‘Uncle Benny and Camp Wah-Kon-Dah,” in ‘Sabra Scene: News and Notes from the Camp Sabra Alumni Association,” Issue 6, March 2007, http://www.camphawthorn.com/Newsletter2007c.pdf; ‘Camp Wah-Kon-Dah Reunion Commemorative Pamphlet,” October 20–21, 1989, 2–3.

- For an excellent discussion of the American camping movement’s association with Native American folklore and its expression in Jewish camping, see Gary Zola’s analysis of Progressive Era educators/writers/camping enthusiasts Ernest Thompson Seton and Luther and Charlotte Gulick, in ‘Jewish Camping and Its Relationship to the Organized Camping Movement in America,” in A Place of Our Own: The Rise of Reform Jewish Camping, ed. Michael M. Lorge and Gary P. Zola (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2006), 9–14; Leslie Paris, Children’s Nature: The Rise of the American Summer Camp (NY: New York University Press, 2008), 189–219; Rayna Green, ‘Poor Lo and Dusky Ramona: Scenes from an Album of Indian America” in Folk Roots, New Roots: Folklore in American Life, ed. Jane S. Becker and Barbara Franco (Lexington, MA: Museum of Our National Heritage, 1988), 79, 80, 82, 83, 93; Zola, ‘Jewish Camping,” 13–16. Zola gives examples of ‘American Jewish camps [that] took Native American-sounding monikers: Cayuga, Dalmaqua, Jekoce, Kennebec, Kawaga, Ramapo, Seneca, Tamarack, Wakitan, Wehaha, Winadu, and others.” Consider Camp CEJWIN, Port Jervis, New York, founded 1919, by the Central Jewish Institute, and Camp Modin, founded in 1922 in Belgrade, Maine, by Jewish educators Isaac and Libbie Berkson and Alexander and Julia Dushkin. Modin, located between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, is associated with the story of Hanukkah and the great heroism of the Maccabees.

- Emily Bazelon, ‘So the Torah Is a Parenting Guide?” New York Times Magazine, October 1, 2006; Wendy Mogel, The Blessing of a Skinned Knee: Using Jewish Teachings to Raise Self-Reliant Children (New York: Penguin, 2001).

- Ellis Lipsitz, ‘Benny Kessler, 1903–1988,” Camp Wah-Kon-Dah Reunion Commemorative Pamphlet, October 20–21, 1989, 1; Paris, Children’s Nature, 213.

- ‘Uncle Benny and Camp Wah-Kon-Dah,” in ‘Sabra Scene: News and Notes from the Camp Sabra Alumni Association,” Issue 6, March 2007, http://www.camphawthorn.com/Newsletter2007c.pdf.

- Michael F. Buynak, ‘Camping in Tough Times,” Camping Magazine, November 1999, http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1249/is_6_72/ai_57815390/.

- A ‘sabra” is a Hebrew term to describe a native-born Israeli. Camp Hawthorn, a private Jewish summer camp sponsored by the Young Men’s Hebrew Association (YMHA) and the Young Women’s Hebrew Association (YWHA) of St. Louis, leased a campground from the Missouri Civilian Conservation Corps in 1938, and later the Lake of the Ozarks State Park, until 1970, when Camp Hawthorn was incorporated into Camp Sabra. Marilyn and Ben Fixman were the lead donors of the St. Louis benefactors who amassed $875,000 to purchase the 960-acre Camp Wah-Kon-Dah, which they donated to the St. Louis Jewish Community Center Associations in 1969, Zola, ‘Jewish Camping,” 13. Zola explains how American Jewish camps gradually replaced Native American motifs with themes from Jewish and Israeli history and culture as Jewish educational camps and camps with an explicitly Jewish mission were founded beginning in the 1920s. Sarna argues that in the two decades following 1940, forty percent of new Jewish summer camps were dedicated to ‘educational and religious aims; they were sponsored by either a major Jewish religious movement, a Hebrew teacher’s college, or a Hebrew cultural institution,” Sarna, ‘Crucial Decade in Jewish Camping,” 28.

- Sarna, ‘Crucial Decade in Jewish Camping,” 45; Mike Kessler telephone interview with Marcie C. Ferris, October 2, 2006.

- Merrill Bauman Stern telephone interview with Marcie C. Ferris, September 12, 2006.