Sweet potatoes flourish in sandy soil. Strawberries announce the advent of spring. Figs sweeten the landscape in August. Canada geese flock to harvest cornfields in winter. Oysters, drum fish, mullet, clams, and spot add a signature dimension to coastal tables, but so, too, do local preparations for stewed pork and pumpkin, black duck and dumplings, peas and doughboys, and sweetened cornbread. The foodways of the coastal South offer a lot more than seafood.

Corn pone, as regional fare and culinary concept, covers a good deal of territory, but Hannah Mary’s pone offers a glimpse into a dish well seasoned with Eastern Shore associations that embrace relations between the well-to-do and the poor, black and white, and memory and practice. Hannah Mary’s pone is not to be confused with cornbread or its corn pone variations. Hers bore only the most distant relation to the familiar miniature cornbread loaves baked in cast iron pans, each pone embossed with the impression of a shucked ear of corn. These corn pones, typically chokingly bone dry beyond the redemption of all liquid, offer something of a dim caricature of their origins as ashcakes baked in hot coals at fire’s edge. Happily, these baked asphyxiations are not the only pones in the world, nor are those other pones without their own extraordinary histories. “Pone” (from the Algonquin apan), as encountered and adapted by Africans and Europeans in the early 1600s in the Chesapeake Bay country, designated bread baked by American Indians. Over time and habit, it acquired more specific reference to cornbread of the American South.

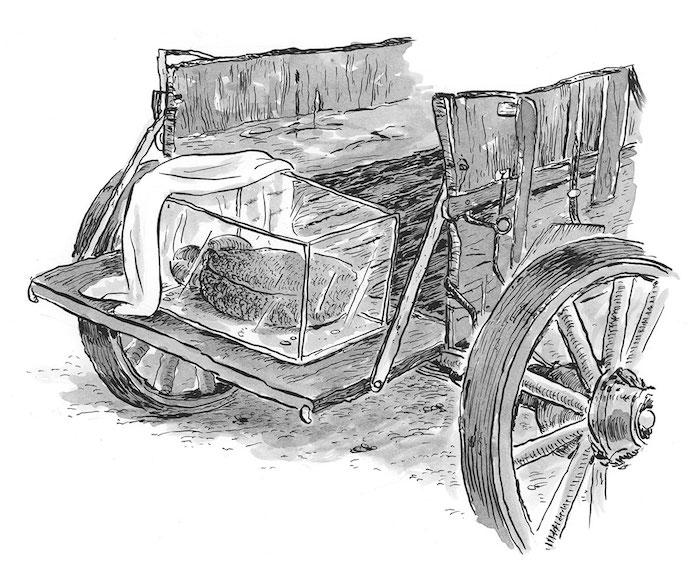

Recollecting her childhood in the town of Lewes at the mouth of the Delaware Bay, Sarah Jastak (born Sarah Ellen Rickards) recounted the weekly appearance in the 1930s of an African American huckster, Hannah Mary Burton. Hannah Mary’s route carried her from her modest clapboard home in the black community located across the railroad tracks, past the high school, and onto McFee Street, where she sold pone, pies, and a bit of garden produce to a white clientele. “She had a wagon pulled by one horse, and you could hear that horse clip clopping down the street,” Sarah begins. “It was just an open old wooden wagon. It just looked creaky and very, very rustic, and I don’t even remember how she had her baked goods stored. Maybe boxes or something, but nothing fancy.” Wistfulness inflects Sarah’s words, spoken with a smile:

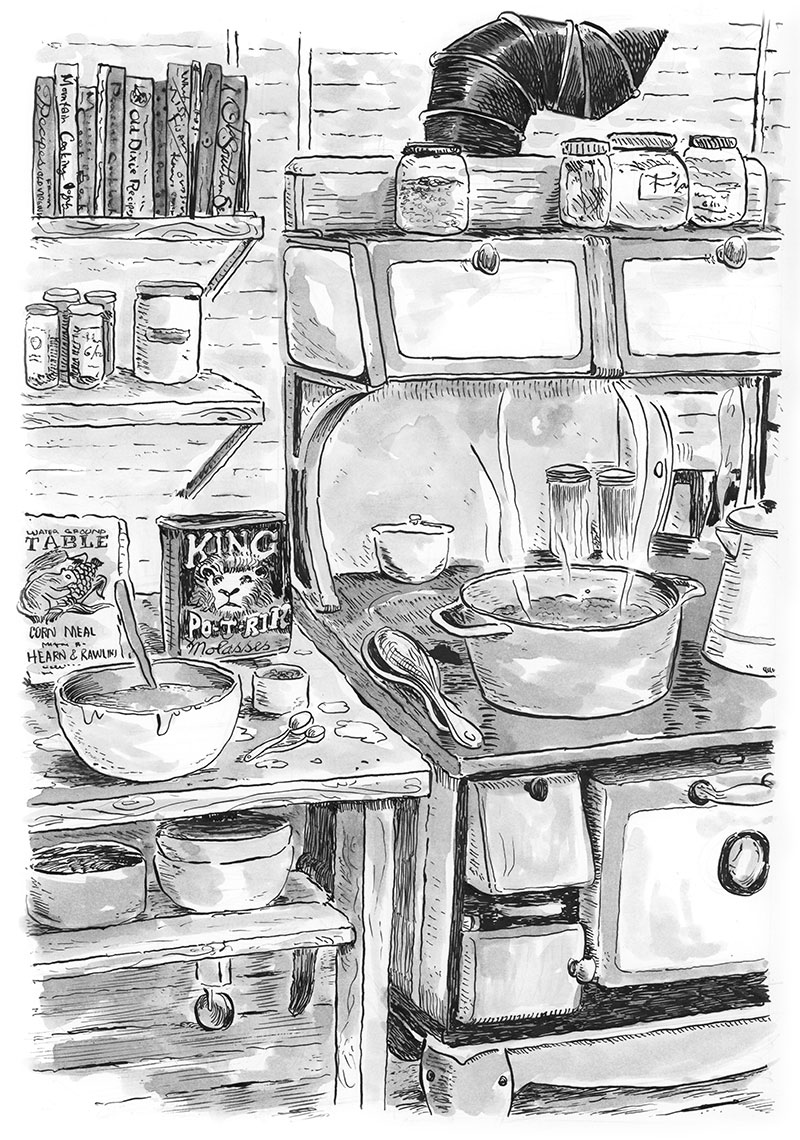

She was a lovely lady . . . And once or twice I tasted her pies, but we really couldn’t afford them because we always made those at home. But Hannah Mary made what she called a “corn pone,” and it was huge. [I]t was certainly more than a foot round and about six, seven inches deep. I don’t know exactly how she made it, but I know it took cornmeal and molasses and water. I don’t know what else she put in it, but I know she baked it. She had an old cookstove range that was wood burning or coal burning, but she would bake it probably for about six hours. And she used to make just one and she would sell it in chunks . . . We didn’t get it every week, but when we bought it, we would always get a quarter of it, and, boy, was it good! You cut it in slices and then either steamed it with lots of butter or you cut it in slices and kind of sautéed it on each side and had it with eggs and bacon. That was good!1

When we write about food we all too often forget core considerations about flavor and texture and smell. Interest in food as an object tends to privilege appearance over flavor, process over aroma, ingredients over consistency. Sarah’s recollections remind us that the food histories of the coastal South engage a wider array of sensations: “It’s very hard to describe what that pone tasted like, except it was delicious. It was not really sweet, but not unsweet. It was dark brown in color. It was not light and feathery; it was of a heavier, denser consistency. It’s very difficult to tell you, except it was absolutely delicious, but it was not feathery like light bread.” With palpable longing, Sarah concludes, “It was just delicious.” Molasses imparted sweetness; the long baking time produced the smoothly dense pound cake– like texture.

Sarah locates Hannah Mary’s pone in the everyday experiences of a street vendor’s rounds and a family’s meals. “We knew she was coming on Saturday morning, and it was always about the same time . . . She kept everything covered with a kind of sheet or something, and she would stop on the street and get down from the bench in the wagon and then go around [to get] whatever it was that she had for sale, and whatever we could afford, we’d get some of it.”

“Life in those days was very much a kind of routine,” Sarah observes. “You knew what time to expect the iceman to come around, what time you expected the milkman. There were just times you expected certain things.” Hannah Mary curtailed her rounds in the winter months, requiring Sarah’s mother to visit her. “It seems to me that my mother would sometimes go out in the wintertime and get a pone. I don’t think [Hannah Mary would] come around in that little open cart [in winter] because it would be cold.”

Sarah sets the table. “Basically, we had it for breakfast. It was something we served in the mornings, on Sunday mornings. We’d get this on Saturday morning when she came around and we couldn’t afford to get it every Saturday. We would have it on Sunday morning for breakfast and with either bacon or sausage or something like that and eggs . . . It was superb.” Sarah laughs, “It would keep for a week without any refrigeration. Of course, it didn’t last long.”

More than once, Sarah, an accomplished cook, confided that Hannah Mary’s pone was a dish she could not replicate: “It was just basically cornmeal, molasses, I think hot water—but she baked it in a huge iron skillet. But, of course, the size of it alone would take a long time to bake, not that I would ever make one that size.” Then, Sarah adds, “Nobody nowadays knows what I’m even talking about when I’m talking about that kind of pone.” As proof, she cites her continuing search for a recipe that replicates Hannah Mary’s giant pone. Recounting her failures, Sarah places two notions in play: the limits of historical knowledge and the reproducibility of past sensation. Hannah Mary’s pone survives only as narrative, a thing that exists in the present only as story.

Mrs. Bertie Powell, resident of Onancock, a waterside town on the Eastern Shore, shared a recipe for “Maryland Yellow Pone” with her friend and neighbor Bessie Gunter, who published it in her 1889 cookbook, Housekeeper’s Companion. Like Hannah Mary’s pone of Sarah’s reminiscence, Powell’s pone is slow baked in a cast iron Dutch oven on a coal-or wood-fired range. Powell’s recipe offers directions couched in a language of time and place. The “genuine” pone derives from an “old” recipe from Maryland. She marks time through meals, situating dinner at midday and a light “tea” or supper in early evening. Properly concocted, the pone will be excellent, but the object in its making is “fussy,” requiring a patient, practiced hand. And, then, there is the problem of translation. Powell implicitly locates the pone in oral tradition and hand-in-hand learning, wondering in her conclusion how the dish will “sound” in print.

From Mrs. Bertie Powell of Onancock, Accomack County, Virginia, in Bessie E. Gunter’s Household Companion (1889):

Scald three quarts or one gallon of meal. Let it stand until cool, then add half teacupful of flour. Stir with cold water until the ordinary consistency of cornmeal batter, and salt to taste. The art in this bread is entirely in the lightening and baking. It is necessary to have a small [Dutch] oven, which you can set inside the stove as it bakes too quickly in flat tins. Make up after [lunch] and pour it in the oven which must be slightly greased. Set the oven with the lid on, on the back part of the stove (mine is a range) where the bread will lighten gradually, but not bake, until tea is over. Then take the lid off the oven, set the oven inside the stove and have a good coal fire, and let the oven remain till morning. A thick crust forms on top which you remove as you cut the bread, only a plate full at a time. You will find the bread as yellow and almost as sweet as poundcake. Remove the crust only as you cut the bread, as that keeps it moist. You can set the oven in the stove and warm the bread as you like. This is the genuine “Old Yellow Pone of Maryland.” It is so “fussy.” [I] don’t know how it will sound in a receipt book, but the bread is excellent. —Mrs. B.P.

Contrary to Sarah’s surmise that the art of Hannah Mary’s pone is forever lost, it endures in some families as a seasonal tradition. My friend Bill McIntire, a Lewes native, wrote me, ” We just always have it as a side at Christmas morning breakfast with bacon, eggs, scrapple, etc., there’s always some left over for subsequent breakfasts, but we never had it any other time. The pone is large, like I said, so often one pone will get split up so that several households can have some for their Christmas.” He poses a question for which he has no answer: “I wonder when in history it morphed from being an everyday food to a holiday treat—it does seem to be a pretty widespread tradition to have it at Christmas in Sussex County.” The custom of baking a cakelike pone for Christmas may or may not be widespread, but it should reassure Sarah that all is not lost. Then, Bill offers an afterthought, “My dad said it was called ‘poor man’s scrapple,’ but that seems like an awfully poor man.”2

Bill provides a recipe that yields two large pones in three-to four-quart Dutch ovens. Even when the recipe is halved, Bill notes that it’s still a lot of pone. Adapted for a modern oven, it no longer requires overnight baking:

9 cups cornmeal (Hearn’s White water-ground, available at Shockley-Reed) 3½ cups all-purpose flour

1 cup Po-T-Ric dark Molasses (Also add 1/4 cup Grandma’s Molasses because Po-T-Ric isn’t as “strong” or as “sulfurous” as it used to be.)

1½ cups sugar

1 tsp soda dissolved in warm water in cup used to measure molasses

3 “scant” Tbsp salt (measure it and shake a little out)

Boil water, a teapot or saucepan full

Scald meal in a large container with boiling water, adding a little at a time and stirring. Get all the lumps out, making a “rather thick” batter.

Thin down with “lukewarm” water

Add flour

Cool down with “tepid” water until “soupy like thin pancake batter”

Add molasses & sugar, stirring all the time

Add soda & salt

Pour into 2 well-greased heavy pots

Bake at 500 degrees for ¾ hour. Watch it, you want it to be a rich brown. Then cover it and turn the oven down to 300 degrees. Bake 4 hours in all regardless of the size of the pot. Leave the lid on after removing from the oven until cooled.

Sarah’s childhood pone, purchased from the back of Hannah Mary’s wain, Bill’s winter holiday table, and Mrs. Powell’s older recipe for a “Maryland Yellow Pone” triangulate the historic place of this pone in the culinary landscape of extreme southern Delaware, the lower Eastern Shore of Maryland, and adjacent Virginia. The dish, already deemed old in the 1880s, recuperates memory. Mrs. Powell lards her narrative with asides on art and antiquity. Sarah and Bill do the same, extending those associations to race and class. Sarah, Bill, and Powell together voice uncertainty about the translation of memory into action. Theirs are pones best consumed through listening and savored in the imagination.

This essay appears in the Coastal Food issue (vol. 24, no. 1: Spring 2018).

Bernard L. Herman, George B. Tindall Distinguished Professor of Southern Studies and Folklore at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, works on the material cultures of everyday life and the ways in which people furnish, inhabit, communicate, and understand the worlds of things. His teaching and research cohere around teaching and public engagement and a deeply held belief that work of the arts and humanities finds its first calling in the public sphere. He also grows oysters on the Eastern Shore of Virginia, where he cultivates a “library” of fig varietals.NOTES

- Sarah Jastak, interview with Bernard L. Herman, March 17, 2011, and May 19, 2012.

- William MacIntire, personal communication with Bernard L. Herman, August 8, 2012.