In today’s food and beverage world, the adjective craft often signifies more than technique or ingredients: it points to scale, agency, and audience, to small-batch creations just inventive enough to attract discriminating publics. Trace the word back, though, and its meanings broaden. As archaeologist and historian Alexander Langlands explains it, the Old English cræft referred to making undertaken with a savvy resourcefulness, a combination of skill and ingenious adaptation. Cræft encompassed not only manual dexterity, but also the surprising repurposings of poetry, the thrifty management of time and materials, and the negotiated give-and-take of relationship-building.1

This expansive yet nuanced definition helps us reconsider today’s modes of production and assignments of prestige—moments when acts of assembly are framed as masterful and times when we construe them as mindless, monotonous labor or as frivolous play. If chef and cook call to mind gendered, classed, and racialized distinctions in the context of culinary skill for hire, craft and cræft shed light on similarly fraught spaces of production and consumption: artisanal workshop, factory, home. We might ask, for instance: In a region in which cured hams and slow-cooked barbecue are beloved alongside ready-to-eat Vienna sausages and red hot dogs, whose craftiness counts when it comes to meat processing?

I

In the American South—where “zealous feelings about hogs” persist—iconic meatcrafts like country ham, barbecue, and smoked sausage have historically helped to manage the excesses of autumn slaughters. Craft processes like these are practical by definition, yet the label also builds in assumptions about value. We might mark such practices as artisanal, that is, as skilled aesthetic behaviors demanding both “patience and memory.” When makers apply the weight of historical precedent and the spark of personalized engagement, we might call their work authentic (and pay more for it). Such is the case with three meat processors profiled in the oral history series Cured South, men whose intergenerational apprenticeships and context-based calibrations of “touch, feel, smell, taste” have earned them titles that include curemaster and Fleischermeister(master butcher), as well as premium prices for the goods they produce.2

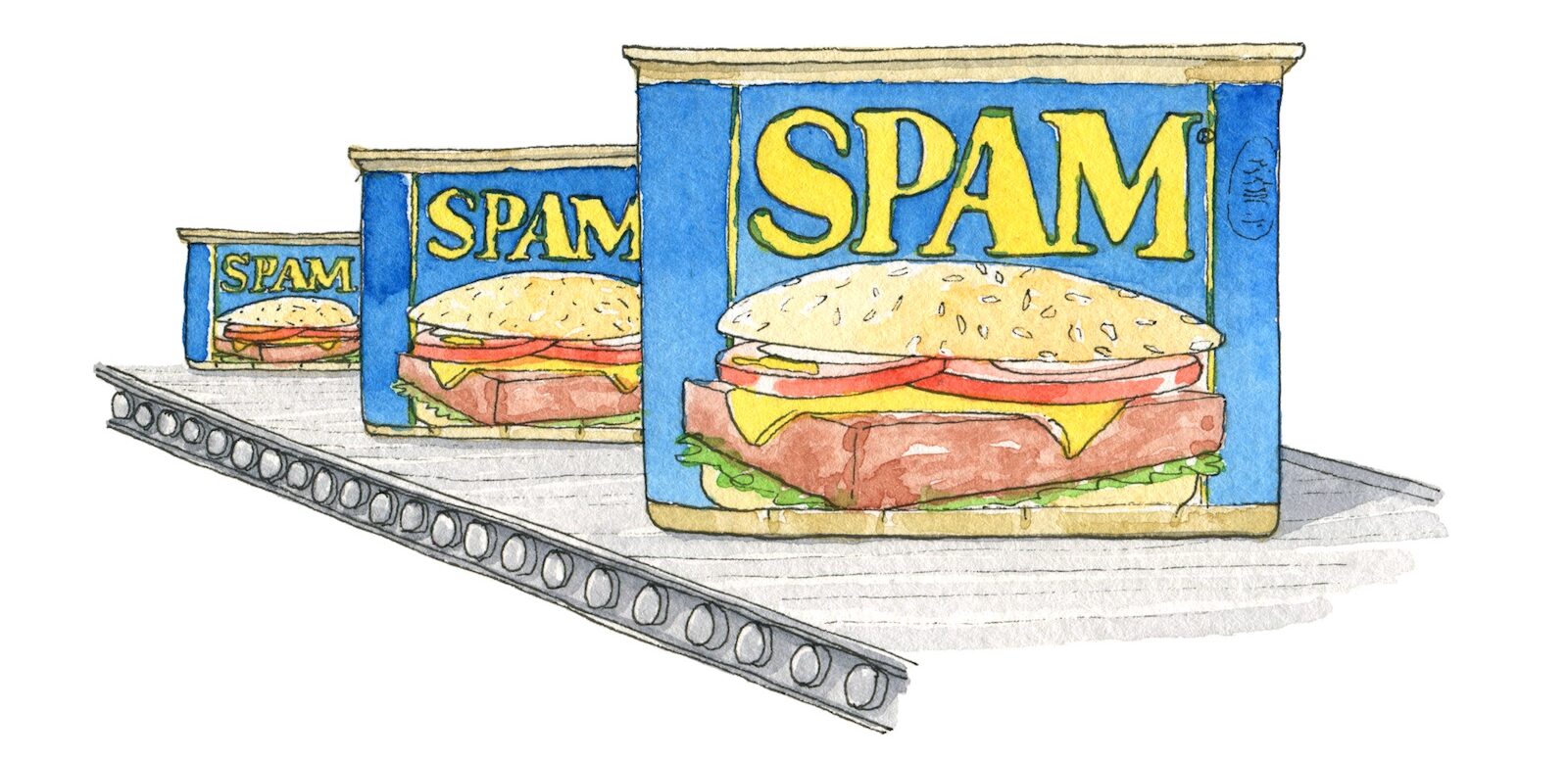

Then there are the meats more commonly associated with the adjective processed: hot dogs, potted meat, deviled ham, Spam. All are foods efficiently presteamed rather than painstakingly cured or deliberately basted. All are mechanically uniform and convenient, ready to be popped in the mouth during work or play, eaten from a dinner pail or on the seat of a bass boat, nibbled from finger sandwiches at a ladies’ luncheon. Unlike the technique-centered talk that dominates discussion of artisanal meats—and despite the Southeast being one of America’s major pork-producing regions—when it comes to processed meats, cultural focus tends to pull toward how they are amended and eaten, rather than to how they’re fabricated: Do you eat baloney fried, between slices of mustard-slathered white bread, or as a pickled snack? Does a fully loaded dog include both chili and slaw? What secret additions make the best ham salad? Books that celebrate barbecue’s skilled and discerning pitmasters fill entire shelves. But what do we know about the people who emulsify and smoke our franks?3

Those laboring in America’s crowded slaughterhouses and packing plants became a bit more visible during the recent pandemic; as COVID-19 sickened workers, consumers contemplated with alarm sparser breakfast tables and more expensive suppers. The Trump administration declared these facilities “critical infrastructure” and invoked the Defense Production Act to keep their often socially, physically, and politically vulnerable employees on the job. While the executive order underscored the power of food conglomerates, the vulnerabilities of complex supply chains, and the symbolic importance of meat in the American diet, it also prioritized products rather than makers—revealing a sense that (factory-) processed foods occupy a distinct conceptual space. Craft, we tell ourselves, is unprocessed: decoupled from assembly lines, transparently constructed, linked tightly to maker choices, and expressing pleasant irregularities and even frailties that remind us of its human roots. In contrast, processed meats have both mysterious origins and unnaturally long lifespans; they are uniform objects whose close contact with machines apparently precludes designations such as “masterful.” The people imagined to mediate between raw materials and saleable products in these contexts—if considered at all—are not artisans but hair-netted, white-smocked abstractions, “fungible widgets” rather than conscious agents.4

Certainly, assembly lines fragment and frenzy processes. Yet surviving in and excelling on the factory floor requires skill, power, and knowledge: rhythm with one’s team, a decisive feeling for form and technique, physical endurance and fine-tuned social coordination, and a kind of cleverness despite constraints that has been pejoratively called crafty. If we approach craft solely as a meticulous process in which makers retain maximal control, we ignore the cunning ways people respond within systems that prioritize anonymity, predictability, and repetition-based efficiency.5

And then there are domestic spaces, the ostensibly private and noncommercial sites of material production most familiar to many of us. Here, overt emphasis on making is often named, gendered, and dismissed as hobby—linked to an abundance of personal time and resources, and thereby to silliness or wasteful extravagance. Alternatively, subtle knowledges associated with women and domestic spaces—understandings of the body, local ecologies, and social systems—have historically been simultaneously recognized and repudiated as witchcraft. In any case, although plenty of efficacious, careful, and powerfully appealing work is completed outside for-profit workshops, it is rarely counted as craft in the visible and venerated sense, especially when that making involves repetitive labor and produces ephemeral, essential, everyday goods.6

Much, for instance, has been written about the art of hog-butchering (as a first step in the creation of whole, durable, and celebrated objects like country hams), but fewer words and pictures document processes such as rendering lard and making bulk sausage—tasks (not arts) often completed (by women) on the days following the Big Event, and in more private, notably domestic, settings. Considering craft primarily in terms of vocational specialization, we fail to notice meat produced during what one Texas writer called “hog-killing mop-up work,” as well as the working-class women and people of color who have prepared and served bulk sausage in the American South.7

II

Composed of ground rather than coherent carvings, variable in shape and flavor, sausage is sometimes cast as suspiciously impure. Yet it marbles records of southern food. Sausages appear in colonial plantation cookery books, spiced with Caribbean flavors. Diaries record that sausage satisfied houseguests at a South Carolina debutante party just after that state seceded from the Union; it was gifted to ruined elites at the end of the war, when Confederate currency became worthless. During the 1930s, “Mrs. Wilkerson’s pepper-hot sausage” was among the items sold at North Carolina curb markets, and Annie Fuller and Dora Hayes—women in

their late sixties who had successfully transitioned from cotton production to live-at-home subsistence farming—offered country ham and sausage to a Federal Writers’ Project fieldworker when she visited their property in Richlands, Alabama. In subsequent decades, Andrew Young remembered mornings spent at Paschal’s Restaurant in Atlanta, eating sausage and biscuits while discussing recent news with fellow civil rights leaders.8

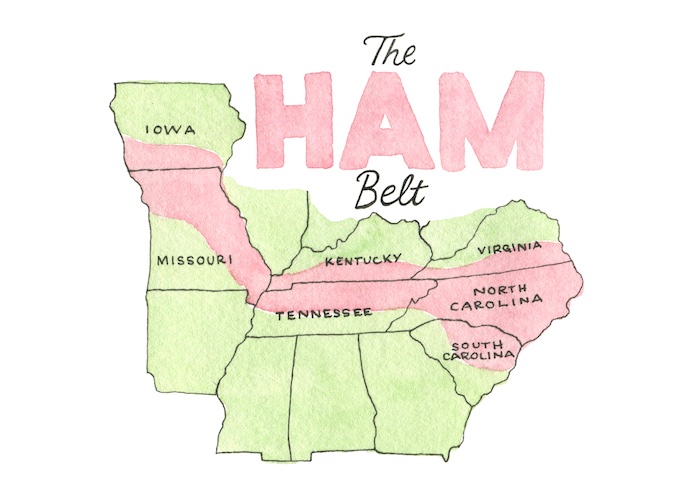

Like the ham and barbecue heralded as foundational southern foodways, sausage is linked to the temperate climate, mast-filled deciduous forests, and peanut fields that helped pigs flourish in the Upland South. Pork produced in “the Ham Belt”—a band that extends across the stacked states of Iowa/Missouri, Kentucky/Tennessee, and parts of the Virginias and the Carolinas—made its way “on the hoof” to the cotton- and rice-centered Deep South, but it also circulated in preserved forms. Well into the twentieth century, many families in the South, like their peers across the country, also kept a few pigs on hand for winter meat. Making sausage allowed southerners to stretch seasonal surpluses, creating distinctive flavors and inhibiting spoilage by grinding meat scraps together with fat, salt, sugar, herbs, and spices.9

As Indigenous people have long known, woodsmoke is an additional way to prolong meat’s shelf life in the face of heat and humidity. Among many groups worldwide, ground meats meant for smoking have been encased in intestines previously turned inside-out, soaked in brine, and scraped clean. But that process involves sensory and social indignities avoided by those who can afford to. Maya Angelou detested the smell of hog guts, but her grandmother made her deal with them anyway, saying, “All poor people need to know how to do some of everything, and a poor colored woman even more so.” Alternatives to “natural” casings include small cloth sacks or washed and dried corn husks, which in the southern mountains were packed with seasoned meat and tied with “corn fodder, bear grass, or a string,” the resulting shuck sausage hung to cure in a smokehouse. Moved out of the house and off the farm, smoked sausage shifts in value. Today, companies like Meyer’s Elgin Sausage in Texas and Coleman’s Sausage and Specialty Meats in Louisiana use scaled-up family recipes to meet consumer demand for smoked links that take pride of place at fundraisers, weddings, and cookouts.10

But not all sausage is smoked or fermented. Fresh forcemeats, such as ground breakfast sausage, have also been important in the South. In the early 1990s, Kentuckians on small farms reported that their fresh-ground sausage generally incorporated 30 percent fat (one part fat to two parts lean) and was seasoned to personal preference, perhaps 1 c. salt, 2/3 c. sage, 2 T. black pepper, 1 T. red pepper, and 3 T. brown sugar for every twenty-five pounds of meat. Today, blocks of bulk sausage are most likely to be found in supermarket freezer sections, but until electricity was widely available, uncured sausage was also preserved by potting or canning it in the fall and storing it in cold cellars or can houses through the winter. One man remarked that before 1945, when families were able to purchase freezer chests or rent space in the Robertson County, Kentucky meat locker, “Everything [meat] was put in a fruit jar.”11

III

Bottled sausage shows up regularly in oral histories from Indiana to Utah, New Mexico to North Dakota. In June 1940, Russell Lee photographed Mrs. George Hutton of Pie Town, New Mexico, reheating homegrown sausage she’d canned the previous winter. Home-canned sausage is also broadly documented in southern states. Henrietta Lewis Logan’s family in Lee County, Virginia, had a piano and many good books in the 1930s, but no electricity; a privately organized co-op didn’t start providing power until November 1939. She remembered that before her home had a refrigerator or freezer, “Sausage had to be ground and made ready for canning” by “the women folk.” This involved partially frying sausage patties, and it was “greasy, hard work,” compensated in part by the delicious aroma of cooking sausage, in part by the promise of convenient future meals. When Iris Carlton-LaNey interviewed ten matriarchs in the early 1990s, they also remembered bottled sausage as important to home economies in Duplin County, a bright-tobacco area of North Carolina’s inner coastal plain. Through the middle decades of the twentieth century, the Black managers of these self-sufficient farms “canned everything,” including peaches, string beans, okra, cabbage, and other homegrown produce. When they killed ten or eleven hogs each December, one woman recalled, they salted and hung the pork in the smokehouse but “canned sausage in lard.”12

How does one “can in lard”? The 1921 Ball Blue Book did instruct its users to process jars of fried sausage packed in hot grease: as in its recipes for fried brains and fried kidneys, partially

sealed jars of precooked forcemeat were to be boiled for ninety minutes in a water bath. But the next edition (1926) recommended draining off all grease, packing the fried sausages tightly, partially sealing, then processing the jars in boiling water for three and a half hours or for just an hour in a “steam pressure cooker” at fifteen pounds pressure per inch. Fabiola Cabeza de Baca’s Spanish-language instructions for canning chorizo, prepared in 1931 on behalf of New Mexico’s Agricultural Extension Service, directed canners to fry the sausage patties in butter, then pack and process them at fifteen pounds pressure for fifty minutes. These shifting instructions for meat canning reflected emerging knowledge about the relationships among low-acid foods, heat, and Clostridium botulinum spores, but they also responded to the increasing availability of affordable home pressure canners, which can reach temperatures necessary to kill spores not inhibited by other means.13

It is possible that when Carlton-LaNey’s Duplin County consultant reported “canning sausage in lard,” she was talking about potting it: packing it hot in fat-filled containers without further processing. This ancient method of storing meat relies on high initial cooking temperatures, low moisture and oxygen levels, physical barriers, and cool ambient air to reduce the growth of microorganisms, and it persisted in the United States until at least the mid-1980s. Oral histories recorded in the late twentieth century describe people packing patties and balls of raw sausage in large dairy crocks, weighing the sausage down with a plate, and baking it; when the rendered fat cooled, it had covered the sausage. A related method involved first frying the ground sausage medium-well before placing it into crocks and covering it with hot grease. These containers were filled in late fall or early winter (after hog harvesting) and stored in unheated outbuildings, where—crucially—they stayed cold, or even frozen, until spring.14

Potted sausage was not exclusive to the South, but the method’s prevalence here is linked to place: to the cold winters of the southern mountains; to fields of peanuts and woods filled with pig-pleasing chestnuts, beechnuts, and acorns; to banks of clay; and to pockets of natural gas that could fuel superhot furnaces. The clay and gas, in turn, drew potters and glassblowers who created the storage vessels on which this method of food preservation depends.

IV

In the mid-1870s, food purity advocate John Cowan recommended that home preservers across the nation use nonporous “stone jars” (i.e., glazed stoneware) that could be “corked up, or otherwise made air-tight”; his peer Eunice Beecher advised young housekeepers to keep these “stone pots” in their preserving toolkits alongside cans, bottles, closures, and a bag for straining jelly. Stoneware protected acidic fruits and pickled vegetables from the corrosion that occurred when they were packed in metal containers, but it had other uses as well.15

Stoneware fruit jars safeguarded food in rural areas into the first decades of the twentieth century, and one center of production was the clay beds of the Appalachian foothills. In North Georgia, the Meaders family pottery (est. 1893, near Cleveland, White County) fired three hundred to four hundred fruit jars at a time, and the family always kept several from each kilnload for their own pantry. Arie Meaders filled the ceramic jars—in quart, half-gallon, and gallon sizes—with whole or mashed berries and sorghum syrup, then sealed the wooden lids with beeswax or wheat starch, followed by clean cloth and waxed brown paper. Stored in a cool room, the berries generated a fine wine. Mostly cooked sausage patties could also be kept in these stoneware jars, or in the crocks that potteries produced for pickles and butter.16

Although people in the region could buy glass jars with zinc caps just after the turn of the twentieth century, the bottles were expensive, smaller than the stoneware fruit jars, and, above all, fragile. Arie Meaders’s mother began to put up fruit in half-gallon glass jars around 1908 or 1909, much to her community’s chagrin. In a 1978 interview, Meaders recalled neighbors saying, “Liddy, you’re gonna get killed is what you’re gonna do. You’re gonna kill your family with them glass cans. Why, they’ll break in the food and every one of you will die!”17

But glassmaking also flourished near the coalfields, and the advent of strong, fully machine-made tempered canning jars around the turn of the century introduced a new element to potting sausage. Glen Vanoy described how his people in central (Casey County) Kentucky fried sausage patties or balls and packed them into Mason jars, then ladled hot sausage grease to within an inch of the rim. After adding a rubber ring and a glass-lined zinc lid, sausage potters turned the bottles “upside down so that the sausage grease will be to the top. And then after it cools, then you can turn it back and it [the grease] will stay up there. That’s to preserve it, to keep it fresh and good.” These packed bottles and crocks (the latter covered with a clean beeswax-dipped cloth) were stored in cool cellars or spring houses, and their contents removed and reheated when wanted. Both the cold storage and frying the sausage before eating contributed to this method’s success: botulism spores don’t like refrigeration, and botulism toxins can be denatured by high heat after containers are opened.18

In 1924, West Virginia’s Hazel-Atlas Glass Company broke ranks with other big bottle manufacturers by retaining a recipe for “Fried Sausage Stored in Lard” in its canning manual, alongside a newer recipe that used pressurized steam. At the same time, it highlighted the environmental and geographic limits of potting without further high-heat sterilization: “This method is quite satisfactory in cool climates, but products will not keep indefinitely without turning rancid in very warm climates.” Historically, those in the Ham Belt and the mountains could get by using the older method, but consistently cold winters in Upland states are not as common as they used to be. As ninety-five-year-old Pleasants County, West Virginia native Grace Hashman observed in a 2012 interview, “But we don’t [store sausage] that way now. You put it in the freezer. [Frozen sausage] ain’t good [tasty] like it was when we [potted our own sausage], but you don’t have winters that will keep it now. Sometimes you go to store it and it gets too warm.” Food scientists today caution that bottled meats meant to be stored at room temperature should always be pressure-canned, not boiled in a water bath.19

V

State and county fairs have long publicly conferred value on home-canned foods, awarding silky ribbons to the jars of sparkling jelly or carefully packed pickles that line the shelves of Home Arts buildings. But bottled meat looks ugly: soft-edged chunks press up against glass, suspended in separated broths; pale browns and grays show through streaks of congealed fat. Then, too, the sad state of Spam fresh from the can is legendary. Yet the physical appearance of home- and factory-processed meats belies other kinds of appeal. To be cræfty is to act adeptly with an understanding of material properties and social parameters, making efficient decisions responsive to resource constraints, aesthetic preferences, and local landscapes. Metaphorical topographies include patterned ways of making and serving that cultivate shared tastes alongside networks of pleasure and obligation.

During the 1940s and 1950s in Dungannon (Scott County), Virginia, for instance, “hog killing was a ritual when it got cold enough.” Jenette Chapman remembered that rituals of preservation soon followed: “Later, Mama would fry up sausage cakes and can them for the coming year.” Women pooled their skillets in order to cook patty after patty, finding that shared work also created shared space for story. One day, in 1940, young Ruth Winkle’s family butchered three hogs in the mountains of eastern Kentucky; her friend Oda Flynn came to help her process the resulting tub of sausage. As Ruth related in a 2012 interview, the women fried patties all day together, topping off the full jars with boiling grease and then turning them “upside down so that grease would seal the jar good.” As the day wore on, though, twenty-two-year-old Ruth could no longer contain her news, and she swore Oda to secrecy: she and her beau were eloping the next day. Cræfty, for sure.20

Most of the women in Carlton-LaNey’s study, like many farm women in the United States through midcentury, regularly “gathered for work in small groups of relatives and neighbors,” sometimes as part of usda-affiliated Home Demonstration Clubs. Norine Saville Snider of Montgomery County, Virginia, says that into the 1980s and beyond, her extended family convened near Blacksburg every Thanksgiving to butcher the group’s hogs, sometimes numbering more than a dozen. “The person who did most of the work and never stopped was Mama,” she told a Roanoke Times reporter in 2016. Claudine Saville not only “made sure we had everything we needed,” but she pressure-canned tenderloins and sausage in the basement kitchen that had been outfitted for meat processing and canning. Norine helped, too, rolling balls of ground sausage for her mother to put in the jars.21

People tell me that the flavor and tenderness of any meat—from bear and venison to chicken and beef—improves when it is put up in jars. Still, they point to bottled sausage as distinctively delicious. Anne and John van Willigen write that those they interviewed “often praised the flavor of sausage preserved [in fat], which apparently resulted in fresher-tasting sausage than that stored in sacks” outdoors in smokehouses. And the 1924 Hazel-Atlas manual proposed that bottling improved on already tasty older potting methods, noting that sausages would “retain their fresh flavor much longer when packed with hot fat in closed glass jars, than when open jars, crocks, or buckets are used.”22

Shelf-stable products can telegraph social taste as well, adroitly smoothing encounters and gesturing toward gentility. Materially persistent, preseasoned yet versatile, even commercially canned meats help maintain norms of hospitality. Though industrialized labor (rather than homegrown resources) makes these kinds of processed meats affordable, Spam and other canned meat products can help stretch a meal, facilitate a shared adventure, or top a cracker for an unexpected guest. And while squat, pallid, and caseless Vienna sausages are no more physically attractive than fried sausage patties, unlike their home-canned cousins they need not be refried to be edible on a hot day. The Vienna sausages made in Chicago and Minnesota at the turn of the century were suspended in broth; notably, in 1938, when Bryan Packing Company of West Point, Mississippi, began manufacturing the first Vienna sausages in the South, workers packed them in oil. According to one historian, that distinctive feature—one that echoes patties sealed in lard—helped popularize Vienna sausages as a regional foodway. Bryan Foods still operates under the slogan “The Flavor of the South.”23

VI

Shared taste preferences thus form the backbone of regional identities. Consider biscuits and (sausage) gravy, a meal common across the United States, but one that Southern Living magazine calls “one of the South’s signature dishes.” It anchors many a chain hotel breakfast buffet as one of the few hot “homemade” items available, and it is included in Fannie Flagg’s Original Whistle Stop Cafe Cookbook, a collection that blurs the line between the still-existing Irondale Cafe and the fictional Whistle Stop Cafe, the centerpiece of Flagg’s novel about a midtwentieth-century Alabama town. As the meal’s symbolic resonance has grown, it has moved into other public spaces, including a semiannual fundraising breakfast at Galax, Virginia’s Glenwood United Methodist Church, where sausage gravy is the event’s centerpiece, served on “split biscuits hot from the oven.”24

Any good cook or caregiver knows that “hot from the oven” is no easy feat: calibrations of available time and effort are crucial elements of these crafts. Even before commercial outfits like Tennessee Pride (est. 1943, Nashville) and Bob Evans (est. 1948, Appalachian Ohio) sold frozen sausage gravy, Hazel-Atlas offered a recipe for home-canned sausage gravy, a move that made bottled sausage a convenience food. The 1924 instructions called for “adding a little flour and water to the fat in which the sausage has been cooked.” This mixture, rather than straight lard, was poured hot over the precooked sausage and processed in a pressure canner. (Today, in addition to selling canned corned beef hash and Vienna sausages, the Libby’s brand also offers canned “country sausage gravy,” no freezer space or electricity required.)25

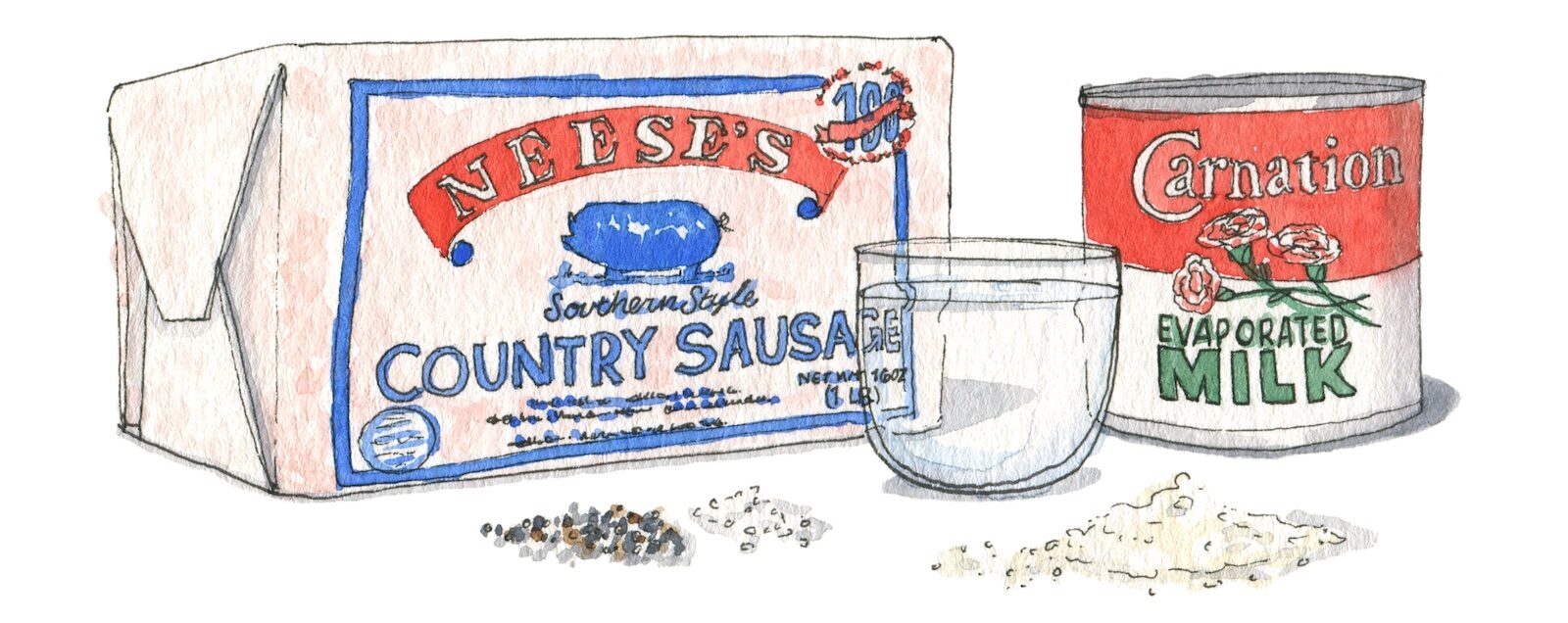

When sausage-making itself moved largely behind factory walls, assignations of artistry shifted elsewhere: to the ability to make a smooth roux or a flaky biscuit. In 2009, Ruth Shropshire described the Galax fundraising breakfast as both a way to “share in a community gathering” and an opportunity to demonstrate personal ability: people reported that her sausage gravy was the best they’d ever eaten. Shropshire’s specialty relies on store-bought sausage: she browns a half-pound of crumbled Neese’s sausage in an iron skillet, stirs in 1/4 c. flour and lets it cook for a few minutes, adds 1 c. canned evaporated milk and 1 c. water, stirs the gravy until thick, and salts and peppers to taste.26

Consumers compare Neese’s—made in Greensboro, North Carolina—to “the fresh sausage they ate as children.” Where does the resemblance lie? Promotional language points to the sausage’s makeup, rather than to its making, emphasizing a proprietary recipe that features unfrozen local ingredients and zero fillers. Surely the meat’s presentation helps, too: workers package Neese’s Southern Style Country Sausage as a paper-wrapped block, with a logo that harks back to old butcher shop signs. It’s unclear how Neese’s style is particularly southern, though the company does offer other (“country”) products associated with hog harvesting, including souse, liver pudding, and a mid-Atlantic favorite: scrapple.27

Like several other outfits in central and western North Carolina, Neese’s also makes livermush. The food is a paragon of thrift, incorporating locally abundant ingredients that have few other easy uses. Comprised of ground pork liver and assorted head meats, bound with cornmeal, and

flavored with sage and pepper, the fully cooked high-protein blocks can be sliced and fried like scrapple (crispy outside, soft within) or spread like paté and other potted meats. Annual festivals in production centers like Shelby and Marion, North Carolina, celebrate its varied preparations, and it has cast its spell upon characters in Jan Karon’s novels, who consume livermush regularly in fictional Mitford. The homely gray loaf is a hedge against future exigencies, requiring just a few moments and a common skillet to prepare. “It keeps well and you can fry it,” historian Tom Hanchett told Eater in 2016, “which means we Southerners love it.” In the Upper Piedmont, at least, people eat fried livermush on biscuits. They say it tastes like sausage.28

It’s also been said that laws, like sausages, only inspire respect until we know how they’re made. But in sausages as in legislation, the backstory bears considering. It matters, for instance, that Brian Ewing’s 2013 Our State feature on Neese’s sausage is titled “Nothing Fancy.” The headline reminds us that craft—especially in reference to non-elite contexts—is sometimes linked to unconscious instinct rather than to deliberate design, and that so-called authentic craft—because it is associated with handwork and has some functional value—is apparently innocent, plain, uncomplicated, unprocessed.

Soothing narratives about home and heritage, the conflation of “country” with a certain kind of craft, tend to overwrite the agency—indeed, the cræftiness—of women, people of color, and others making (un)waged things in everyday spaces. In 2002, journalist Kathleen Purvis gave a glimpse into how Don Jamison and his son-in-law Butch Allen, rising before dawn, produced forty-four pans of livermush for a small Charlotte family business (Jamison compared his work judging textures and leveling slurry to that of a brick mason). But recent media attention to livermush focuses on owners (not necessarily makers) and origin stories, chefs and their public elevations of a dish linked rhetorically to grandmothers, textile workers, and mountain folk. Similarly, while media reports regularly highlight Neese family recipes and leadership or feature the careers of salesmen and managers, I’ve yet to find accounts that discuss who actually makes the celebrated sausage today.29

VII

Some meatcrafts are valorized for their stable continuity; others have changed due to new food technologies, shifting environmental conditions, and altered rhythms of work and reciprocity. Yet the meanings of bulk sausage and other processed meats still resonate in daily private meals and in annual public gatherings, where people contemplate what counts as “fresh and good,” and what it means to be us (or them). In these negotiations of meaning, labels like craft serve to distinguish among makers, often ironically excluding from recognition and reward those we’ve come to know as “essential” workers, the ones involved in so-called mop-up work, those enmeshed in the daily grind.

Recall that Flagg’s Original Whistle Stop Cafe Cookbook offers up a recipe for sausage gravy. It also features a number of epigraphs, including a note from Ninny Threadgoode to Evelyn Couch, the two characters who populate the novel’s frame story: “Here are some of Sipsey’s original recipes I wrote down.” In Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe, Sipsey Peavey is the “superstitious” daughter of a formerly enslaved woman; she manages the cafe’s garden and does the cooking, along with her daughter-in-law Onzell and son George Pullman (who makes barbecue that is notorious in more ways than one). Ninny’s note about copying Sipsey’s recipes points, perhaps, to the real-life Lizzie Cunningham.30

Flagg’s Whistle Stop Cafe was famously inspired by Bess Fortenberry’s Irondale Cafe near Birmingham. Online accounts of the latter establishment mention “wonderful cook” Lizzie Cunningham; a few also note in passing that Cunningham was Black, or a friend of Aunt Bess. But Mike Fortenberry, who knew Cunningham as a child in the 1950s and 1960s, says that “Miss Lizzie” lived in a room in the cafe during the week and spent the weekends at her own home in Pratt City, a mining town built on the backs of convict labor and later annexed by Birmingham. Her workweek began with a trip to the curb market on Finley Avenue after his aunt picked her up; Cunningham cooked the made-to-order breakfasts and lunches, joining Bess Fortenberry at 4:30 a.m. every morning to prep the day’s food.31

Mike Fortenberry’s memories of Lizzie Cunningham as a skilled, proud, and compassionate “Christian lady” testify to her strength of character. But the public record says little about how she managed her days, including what it was like for her and waiter Ossie Oliver (who reportedly managed all orders from memory) to work in a segregated space, far from home, their labor practically invisible. Is it Lizzie Cunningham’s recipe for sausage gravy that circulates online and in print today? Did she bottle sausage when she began working at the café in the 1940s, or did she purchase it at the curb market or butcher shop? If so, who processed that meat?

VIII

In Work Done Right, poet David Dominguez narrates the cræfty strategies employed by those who exceed the narrow confines inscribed by privileged, patriarchal understandings of craft. His poem “Oxtail Stew” depicts meat processors in packinghouses and in private homes finding ways to “keep something holy” amid bloody knuckles and a tumult of “shoulder, fat, bone, and loose sheet metal,” despite tight budgets and unheralded backstage labor. In the orchestrated music of grinding, sweetening, stuffing, crimping, boxing, labeling, stacking, and wrapping sausage, they insert independent notes: a thermos of stew deepened with chili peppers, a cotton napkin edged in brown crochet, “hot coffee sweetened con canela.” These adaptive assertions of knowledge, skill, and preference not only get the work done, but they “tak[e] back what the work took.”32

The French loanwords we often apply to spaces considered properly artisanal—atelier, abattoir—call up old prejudices, maintaining centuries of linguistic and social hierarchies that effectively minimize the skilled, aesthetic activities taking place in the factory and the middling kitchen. Working harder to understand exactly how the sausage is made—whether home-bottled in gravy, smoked by entrepreneurs, or seasoned in enormous vats—compels us to consider the intersections of tacit knowledge, physical dexterity, social savvy, and sensory power long ago built into notions of cræft.

This essay first appeared in the Crafted Issue (vol. 28, no. 1: Spring 2022).

Danille Elise Christensen is a folklorist and assistant professor in the Department of Religion and Culture at Virginia Tech, where she is faculty in the material culture and public humanities graduate program and the food studies program. Her work centers on the rhetorical positioning of vernacular culture, including home canning.

NOTES

- Alexander Langlands, Cræft: An Inquiry into the Origins and True Meaning of Traditional Crafts (New York: W. W. Norton, 2018).

- S. Jonathan Bass, “‘How ’bout a Hand for the Hog’: The Enduring Nature of the Swine as a Cultural Symbol in the South,” Southern Cultures 1, no. 3 (Spring 1995): 301–20, at 316. See transcripts of Sara Wood’s interviews with Sydney Gordon Meers Jr. (VA), Samuel W. Edwards III (VA), and Stefan Neumann (KY), Cured South, Southern Foodways Alliance, May 1, 2014, https://www.southernfoodways.org/oral-history/cured-south.

- Silas House, “The Indulgence of Pickled Baloney,” Gravy, April 28, 2014, https://www.southernfoodways.org/the-indulgence-of-pickled-baloney; Amy McKeever, “How Lunch Became a Pile of Bologna,” Eater, December 2, 2016, https://www.eater.com/2016/12/2/13799660/bologna-sandwich-recipe-history; Lyndsay Cordell, “The Southern Fried Bologna Sandwich Is a Classic to Try,” Wide Open Eats, September 2, 2020, https://www.wideopeneats.com/fried-bologna-sandwich/. For more on regional hot dog stylings in the South, see Tara Hulen and Thomas Spencer, “In the ‘Ham, the Hot Dog Rules,” Cornbread Nation: The Best of Southern Food Writing, vol. 1, ed. John Egerton (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 155–60; Emily Hilliard, “Slaw Abiding Citizens: A Quest for the West Virginia Hot Dog,” Gravy, Fall 2016, https://www.southernfoodways.org/slaw-abiding-citizens-a-quest-for-the-west-virginia-hot-dog/; and Robert Donovan, “Tour North Carolina’s Old School Hot Dog Stands,” Eater, June 14, 2017, https://carolinas.eater.com/maps/best-north-carolina-hot-dogs.

- Eric Schlosser, “America’s Slaughterhouses Aren’t Just Killing Animals,” Atlantic, May 12, 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/05/essentials-meatpeacking-coronavirus/611437/; David Pye, The Nature and Art of Workmanship (Cambridge University Press, 1968); Taylor Telford, Kimberly Kindy, and Jacob Bogage, “Trump Orders Meat Plants to Stay Open in Pandemic,” Washington Post, April 29, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/04/28/trump-meat-plants-dpa/.

- Michael Holtz, “6 Months Inside One of America’s Most Dangerous Industries,” Atlantic, June 14, 2021, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2021/07/meatpacking-plant-dodgecity/619011/; Michael Owen Jones, “A Feeling for Form, as Illustrated by People at Work,” in Exploring Folk Art (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1987), 119–32; James C. Scott, Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1990).

- Steven M. Gelber, Hobbies: Leisure and the Culture of Work in America (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999); Danille Elise Christensen, “‘Look at Us Now!’: Scrapbooking, Regimes of Value, and the Risks of (Auto)Ethnography,” Journal of American Folklore 124, no. 493 (Summer 2011): 175–210; Danille Elise Christensen, “Materializing the Everyday: ‘Safe’ Scrapbooks, Aesthetic Mess, and the Rhetorics of Workmanship,” Journal of Folklore Research 54, no. 3 (September–December 2017): 233–84; Langlands, Cræft.

- J. B. Coltharp, “A ‘Hog-Killing Good Time,’” Southwestern Historical Quarterly 79, no. 2 (1975): 182–88, at 185; Bass, “‘How ’bout a Hand for the Hog’”; Michael Twitty, “Hog Killing Time: Comments and Commentary on a Southern Plantation Tradition,” Afroculinaria (blog), January 24, 2013, https://afroculinaria.com/2013/01/24/hog-killing-time-comments-and-commentary-on-a-southernplantation-tradition/.

- Marcie Cohen Ferris, The Edible South: The Power of Food and the Making of an American Region (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

- Mark Essig, Lesser Beasts: A Snout-to-Tail History of the Humble Pig (New York: Basic Books, 2015); Greg Gapsis, “Edibles & Potables: The Ham Belt (2012),” Food & Dining Magazine, January 24, 2021, https://foodanddine.com/the-ham-belt/; Rayna Green, “Mother Corn and the Dixie Pig: Native Food in the Native South,” Southern Cultures 14, no. 4 (Winter 2008): 114–26; David L. Thurmond, A Handbook of Food Processing in Classical Rome: For Her Bounty No Winter (Boston: Brill, 2006), 220–22; Anita Dua, Gaurav Garg, and Ritu Mahajan, “Polyphenols, Flavonoids, and Antimicrobial Properties of Methanolic Extract of Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Miller),” European Journal of Experimental Biology 3, no. 4 (2013): 203–08; Biljana Bozin et al., “Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Properties of Rosemary and Sage (Rosmarinus officinalis L. and Salvia officinalis L., Lamiaceae) Essential Oils,” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 55, no. 19 (2007): 7879–85.

- Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, Narrative of Le Moyne: An Artist Who Accompanied the French Expedition to Florida (1591; repr., Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875), 51; John Lawson, A New Voyage to Carolina (London: 1709), 18. Quoting Antoine Du Pratz’s Histoire de la Louisiane (1758), see John R. Swanton, Indian Tribes of the Lower Mississippi Valley and Adjacent Coast of the Gulf of Mexico (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1911), 72. Sue Shephard, Pickled, Potted, and Canned: How the Art and Science of Food Preserving Changed the World (London: Headline, 2000); Coltharp, “A ‘Hog-Killing Good Time’”; Maya Angelou, Hallelujah! The Welcome Table (New York: Random House, 2004), 25; Lesa W. Postell, Appalachian Traditions: Mountain Ways of Canning, Pickling & Drying (Whittier, NC: Ammons Communications, 1999), 88; Joseph E. Dabney, Smokehouse Ham, Spoon Bread, and Scuppernong Wine: The Folklore and Art of Southern Appalachian Cooking(Nashville, TN: Cumberland House, 1998), 184; Linda Garland Page and Eliot Wigginton, eds., The Foxfire Book of Appalachian Cookery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1984), 123; Gregg Meyer and Betty Meyer, interview by Marvin Bendele, Southern Foodways Alliance, July 24, 2007, https://www.southernfoodways.org/interview/meyers-sausage-company; Lynn Dale Coleman, interview by Mary Beth Lasseter, Southern Foodways Alliance, February 18, 2009, https://www.southernfoodways.org/interview/colemans-sausage-and-specialty-meats.

- Anne Van Willigen and John Van Willigen, Food and Everyday Life on Kentucky Family Farms, 1920–1950 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2006), 233, 217.

- Pearl McCall (Daviess County, IN) in Eleanor Arnold, ed., Feeding Our Families: Memories of Hoosier Homemakers, vol. 1 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1983), 47; Renee Thackeray and Reese Loveless, “If Only Walls Could Talk: Thackeray Legacy Homes in Croydon [UT],” April 2015, in the author’s possession; Minnie Ness (ND) in Eleanor Arnold, ed., Voices of American Homemakers (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993), 138; Russell Lee, “Mrs. George Hutton Dishes Up Sausage Made from Her Own Hogs and Canned Last Winter. Pie Town, New Mexico,” June 1940, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives Collection, Library of Congress, http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/fsa.8b25194; Libby Laforce, “Powell Valley Electric Cooperative at 75,” Gateway to the West, Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society, July 2013, 1; Henrietta Lewis Logan, “Happy Hollow,” in Grazing Along the Crooked Road, ed. Betty Skeens and Libby Bondurant (Pounding Mill, VA: Henderson, 2009), 99; Iris Carlton-LaNey, “Elderly Black Farm Women: A Population at Risk,” Social Work 37, no. 6 (November 1992): 517–23, at 518, 521.

- Ball Brothers Glass Manufacturing Company, The Ball Blue Book of Canning and Preserving Recipes, no. 20, edition M (Chicago: R. R. Donnelley and Sons, ca. 1921), 37; Ball Brothers Company, The Ball Blue Book of Canning and Preserving Recipes, no. 21, edition N (South Bend, IN: L. P. Hardy, 1926), 19, in Ball Corporation Collection, box 1, folder 10, Minnetrista Heritage Collection, Muncie, Indiana; Boletin de Conservar, Extension Circular no. 106 (State College: New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts, Agricultural Extension Service, 1931).

- Sally Smith Booth, Hung, Strung, and Potted: A History of Eating in Colonial America (New York: Crown, 1971); Van Willigen and Van Willigen, Food and Everyday Life, 235; Dabney, Smokehouse Ham, 184; Postell, Appalachian Traditions, 88; Page and Wigginton, Foxfire Book of Appalachian Cookery, 123.

- John Cowan, What to Eat, and How to Cook It: With Rules for Preserving, Canning and Drying Fruits and Vegetables (New York: Cowan, 1874), 103; Mrs. H. W. [Eunice] Beecher, Motherly Talks with Young Housekeepers (New York: J. B. Ford, 1873), 475.

- Charles G. Zug III, Turners & Burners: The Folk Potters of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986); Ralph Rinzler and Robert Sayers, The Meaders Family: North Georgia Potters (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1981), 99.

- Rinzler and Sayers, Meaders Family, 100.

- Danille Elise Christensen, “‘Good Luck in Preserving’: Canning and the Uncanny in Appalachia,” in The Food We Eat, The Stories We Tell: Contemporary Appalachian Tables, ed. Elizabeth S. D. Engelhardt and Lora E. Smith (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2019), 132–55; Van Willigen and Van Willigen, Food and Everyday Life, 235.

- Grace E. Hashman, interview by Katherine N. Bills, July 26, 2012, p. 14, box 1, folder 14, Appalachian Foodways Oral History Collection, Berea College Special Collections & Archives, Berea, Kentucky. Other oral histories in this collection note that curing ham properly is increasingly difficult due to climate conditions. See also Tonia Moxley, “Curing a Family Hunger in Montgomery County,” Roanoke (VA) Times, December 27, 2016; “Selecting, Preparing, and Canning Meat,” National Center for Home Food Preservation, University of Georgia, accessed July 21, 2021, https://nchfp.uga.edu/how/can_05/ground_chopped.html. The Hazel-Atlas Glass Company’s manual instructs cooks to “fry sausage, pack in jars, pour hot lard over sausage until jar is entirely full. Be sure to have jar hot before pouring lard in and do not rest on metal tray or table. Close jar at once when filled, allow to cool, and store in a cool, dark place.” Hazel-Atlas Glass Company, A Book of Recipes and Helpful Information on Canning, 4th ed. (Wheeling, WV: Hazel-Atlas Glass, 1924), 24.

- Jenette Chapman, “Glimpses of Yesteryear,” in Grazing Along the Crooked Road, ed. Betty Skeens and Libby Bondurant (Pounding Mill, VA: Henderson, 2009), 138; Ruth Winkle, interview by Chelsea Bicknell, June 15, 2012, pp. 14–15, box 1, folder 29, Appalachian Foodways Oral History Collection, Berea College Special Collections & Archives, Berea, KY.

- Carlton-LaNey, “Elderly Black Farm Women”; Moxley, “Curing a Family Hunger.”

- Van Willigen and Van Willigen, Food and Everyday Life, 235; Hazel-Atlas, Book of Recipes, 24.

- Bruce Kraig, “Vienna Sausage,” in The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink, ed. Andrew F. Smith (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 611; “Bryan: The Flavor of the South,” Bryan Foods, accessed July 20, 2021, https://www.bryanfoods.com/.

- “Sausage Gravy and Biscuits,” Southern Living, accessed June 15, 2021, https://www.southernliving.com/recipes/sausage-gravy-and-biscuits; Fannie Flagg, “Sausage Gravy,” Fannie Flagg’s Original Whistle Stop Cafe Cookbook (New York: Random House, 1993), 67; Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe (New York: Random House, 1987); Skeens and Bondurant, Grazing, 250.

- “The Tennessee Pride Story,” Odom’s Tennessee Pride, accessed July 20, 2021, https://www.tnpride.com/about-us; “Company History,” Bob Evans Restaurants, accessed July 20, 2021, https://www.bobevans.com/about-us/our-company; Hazel-Atlas, Book of Recipes, 24; Libby’s Meats, accessed July 20, 2021, https://www.libbysmeats.com/.

- Skeens and Bondurant, Grazing, 250.

- J. Brian Ewing, “Nothing Fancy,” Our State, January 2013, 141–43, at 143.

- Kathleen Purvis, “Welcome to Livermush Land,” Cornbread Nation, vol. 1, ed. John Egerton (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 117–19; Chuck Shuford, “What Happened to Poor Man’s Paté?” Daily Yonder, November 6, 2007, https://dailyyonder.com/what-happened-poormans-p-t/2007/11/06/; Adam Rhew, “In North Carolina, Livermush Still Wins Hearts,” Eater, September 16, 2016, https://www.eater.com/2016/9/16/12921932/what-is-livermush-north-carolina.

- Purvis, “Welcome to Livermush Land”; Melissa Bashor, “In Cleveland County, Livermush Is King,” Our State, February 23, 2015, https://www.ourstate.com/livermush/; Kathleen Purvis, “Southern Soul of Charlotte: A Mill Town on the Menu,” Our State, October 22, 2018, https://www.ourstate.com/southern-soul-of-charlotte-a-mill-town-on-the-menu/; Neese’s, accessed July 21, 2021, https://neesesausage.com/; Ewing, “Nothing Fancy”; Tatiana M. With, “51 Years on the Job—And Still Going,” News & Record, January 2, 1993; Mike Wagoner, “Neese Family Racks Up a Century of ‘Sausage Success,’” Carolina Coast Online, September 16, 2020, https://www.carolinacoastonline.com/entertainment/around_town/article_73bc5528-f796-11ea-9e33-0b8546df4133.html.

- Flagg, Fannie Flagg’s Original Whistle Stop Cafe Cookbook, 8.

- Mary Jo McMichael, “The History of the Original WhistleStop Cafe,” Original WhistleStop Café Store, May 24, 2019, https://whistlestopcafe.com/about-us/our-history/; “History,” Irondale Cafe, accessed July 21, 2021, http://www.irondalecafe.com/history/; Mike Fortenberry, personal correspondence, July 1, 2021; Two Industrial Towns: Pratt City and Thomas (Birmingham, AL: Birmingham Historical Society, ca. 2013), https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/2438132/pratt-city-and-thomas-the-birmingham-historical-society; Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (New York: Doubleday, 2008).

- David Dominguez, “Oxtail Stew,” in Work Done Right (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2003), 33–35.