A few months ago, longing for an ancestral experience I’ve never had, I went on a bison hunt to Costco, where it is possible to buy rectangular packets of mushy ground meat. While there, I spied another shrink-wrapped package in the prepared foods section, this one containing pastrami beef ribs from a company in Austin. They caught me, those ribs. They reminded me of something deep in the collective past of my people in Louisiana, and of what we have lost.

I’m an enrolled member of the Atakapa-Ishak Nation of Southwest Louisiana and Southeast Texas. Ishak, “the Human Beings,” is what we have traditionally called ourselves and how I refer to us. From the Colonial Era until now some have referred to us as Atakapa, a name that outsiders have given, one that means “man eater.” That sort of flesh isn’t sold at Costco—and, in any case, the term likely refers not to cannibalism but to the specter of enslavement by the Ishak that other Indigenous Nations of the Gulf South feared. Like many Indigenous People of Louisiana, my heritage is ethnically mixed. Our ancestors in the distant past called themselves Ishak because their ancestors did, and so do we.1

If someone were to ask me what Indigenous Peoples ate in Southwest Louisiana, I would mention things that people eat now, such as crawfish or turkeys. I would also name things people forage now, from the popular pecan to the less popular bull thistle. I would describe standing on a midden of rangia clam shells at Four Mile Cutoff, a ship channel in Vermilion Parish. After tasting a rangia clam, a mollusk smaller than an oyster with a somewhat spoiled flavor even when fresh, I find past attempts to commercialize this item laughable in the highest degree. I would also point out that Indigenous People ate bison in Louisiana. To some, this is surprising.2

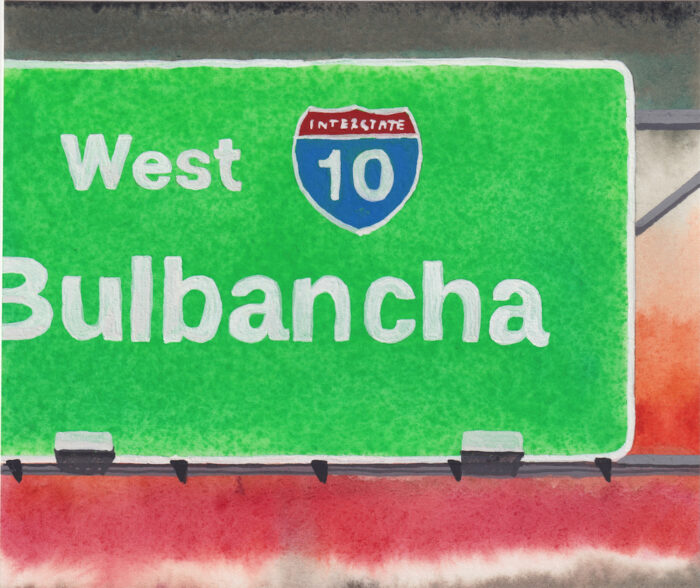

I live in Bulbancha, “the place of other languages,” which colonizers renamed as New Orleans. But some of us still refer to it by its older name, a bit of single-word decolonization. The earliest French colonial visitors to Bulbancha, Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville and crew, recorded seeing three bison napping on the banks of the river. There are Louisiana places named after bison. One such place, Bayou Terre aux Boeufs, in St. Bernard Parish near Bulbancha, still has a significant population of Indigenous People. It is the home of Houma storyteller, artist, and activist Monique Verdin, who notes:

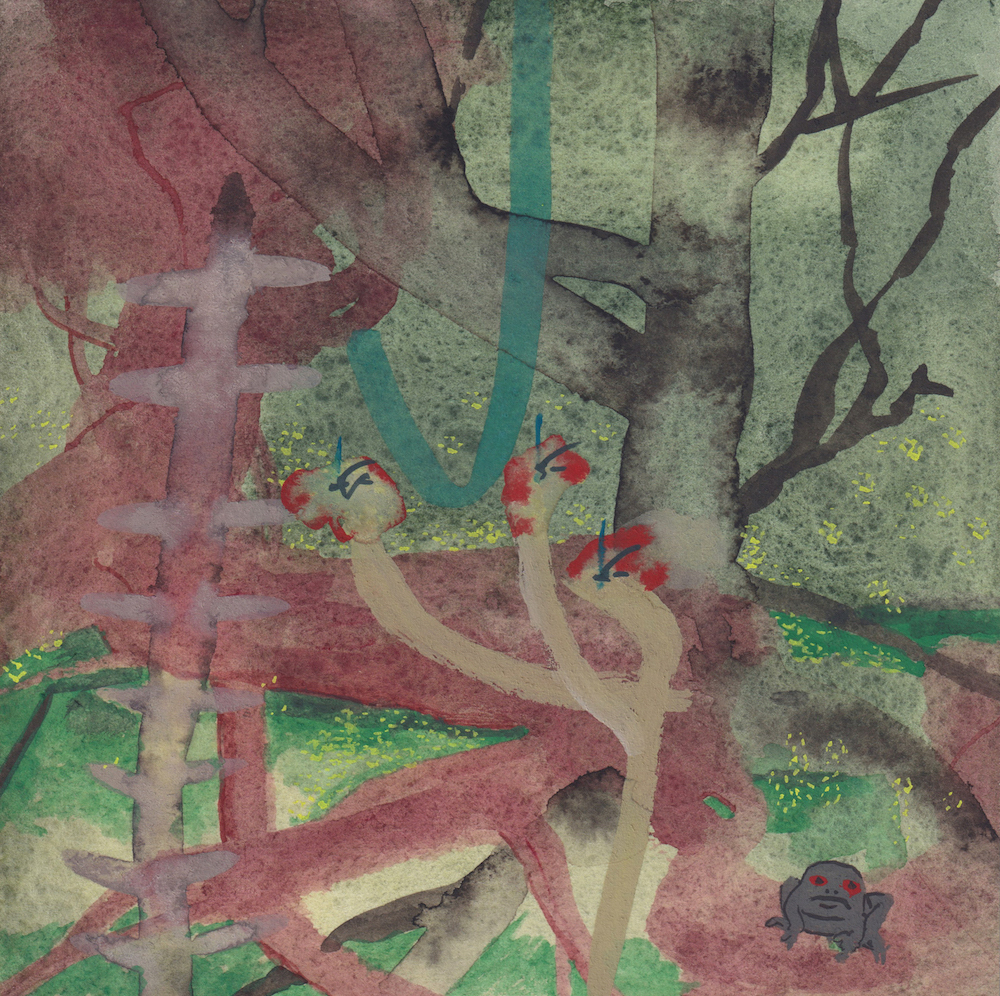

Colonial-era Jesuits described wild bison roaming the lands that bordered the old waterway. The bison were hunted into extinction during the early years of colonial conquest; however, seeds carried on their hides from the northwest hundreds of years ago continue to grow evidence of their southeastern migrations, visible in pockets of remnant prairie hidden between bottomland hardwood forests on slivers of high ground hugging the banks.3

The bison available from Costco was a typical capitalist product—ground with machinery, properly labeled, ready for consumption—but the ribs were different. They had been exported from Texas to Bulbancha, from Old Mexico to New France. They still looked like ribs, even after processing. The pastrami ribs at Costco were much closer to the bison products of the Ishak of old than the actual ground bison of the meat section. Smoked bison ribs were exported by the French from the port across town during the eighteenth century. A box of plat côté, as these ribs were called, appears in French polymath Alexandre de Batz’s 1735 painting Desseins de sauvages de plusieurs nations, which also features an Ishak man and even has a version of the word “Bulbancha” in it.4

Less than a century after de Batz completed his painting, the last wild bison herds in Louisiana gave their final steamy breaths. A recent exhibition of landscape painting from Louisiana and environs at the New Orleans Museum of Art, spanning the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, contains much in the way of detailed depictions of flora and fauna, but not a single bison. I have read about them, and thought about them, and daydreamed about them. I have bought bison meat in butcher shops in Colorado to put in gumbo, and ordered cured bison snacks from Native American Natural Foods, a company on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota whose Tanka Bars are a staple in my jacket pockets. But I myself am removed from bison hunting over several generations and two centuries, with my bison hunting confined to modern American supermarkets, the least Indigenous place for my longing to dwell.5

I miss the bison. I miss them without having met them. I miss something I’ve never had.

Just Of of Memory

I grew up in Baton Rouge, and on weekends visited my older relatives upriver in Pointe Coupée Parish, less than an hour’s drive away. There, I would listen to stories. These stories stretch back into the nineteenth century, though none of them involve bison. They are about other things, such as the early days of a marriage between my great-great-grandparents Villeneuve Fabre, a Frenchman, and Charlotte LeDuff, a Native, living in Pointe Coupee Parish, and how they would argue sometimes in Louisiana Creole, their common language, and how she would get mad and begin cursing him with her Indigenous tongue. She would point at his head and then at his feet, telling him without words that he hadn’t yet put into action whatever idea he was working on, forgetting how to say that in their shared tongue. I would eventually find the saying that eluded her in Lafcadio Hearn’s collection of Creole proverbs.

In Louisiana Creole: “Quand li gagnin kichose dans so latête, cé pas dans so lapiè.”

In French: “Quand il a quelque chose dans sa tête, ce n’est pas dans son pied.”

In English: “When he gets something into his head, it isn’t in his foot.”

I know this story because my late grandfather, Joseph Clifton Fabre Sr., told it to me; and his father, Lucus Anatole Fabre, told it to him.6

I have been involved in the process of cultural reclamation, and while this process encompasses all aspects of culture, my focus has often been on our traditional language, which folks in the know refer to as Ishakkoy (Human Being Talk), and which is erroneously known as Atakapan. A self-identifying word for us other than Ishak is Yukhiti, which can refer to Natives/Indigenous/#ndnz, either from our own nation or any other, and which literally means something along the lines of “the we-people,” or perhaps “the people we are.” As such, the term Yukhiti Koy (We People Talk) appears in the dictionary of our language compiled by Albert S. Gatschet and John R. Swanton. Despite that, the linguists still called the language “Atakapan.”7

There are no more speakers of Ishakkoy from any sort of continuous transmission. That, in itself, is an environmental loss. I have no idea when the last Ishakkoy speaker voiced those words, only that those speakers aren’t around anymore. Various dates have been proposed, however informal, but fairly extensive inquiries at tribal gatherings suggest to me that the last speakers walked on sometime around 1970. Even then, I don’t know when they last spoke Ishakkoy. What remains of their words is mostly in Gatschet and Swanton’s dictionary, as well as in a separate linguistic study by Swanton. Subsequent linguistic studies are based on those. Neologisms are suggested and recorded these days largely in a weekly online language learning group on Facebook made up primarily of tribal members and linguists. New materials, including videos, charts, and example paragraphs, are being produced in the language and are posted there. We had to come up with a phrase for “thank you” and decided on hiwew, based on an adjective meaning “powerful” or “thankful.” Gatschet and Swanton never recorded such an expression of thanks directly. Maybe they didn’t ask. Maybe it just wasn’t important to these exalted, extractive scholars.8

Contemporary linguist David V. Kaufman revised Gatschet and Swanton’s dictionary, and I use Kaufman’s orthography in the main. The word in Ishakkoy for bison is šokon, which means “grass thing.” Bison were a familiar animal and so they were a named animal. There was no need to name the unfamiliar. There was no Bible translated into Ishakkoy, and hence no need for names of foreign fauna such as kamil (camel), as appears in the Choctaw dictionary of missionary Cyrus Byington.9

In 1885, Louison Huntington, an Ishak woman in Lake Charles, Louisiana, spoke narratives that Gatschet recorded in notebooks. These accounts constitute the primary corpus of texts in Ishakkoy. One of these narratives is particularly interesting from a foodways perspective. Given my research on such things, I have translated a salient passage from her account as follows, updating the species identifications to reflect my own research and common terms from my own speech:

The Ishak We People of old lived in villages below here on the edges of the lakes. They planted peach trees there. They planted fig trees there. They planted apples. They planted plum trees there. They planted pumpkins, beans, corn, and sweet potatoes there. They ate venison, bear meat, turtles, gallinules, catfish, sac-a-lait, choupique, gaspergou, ducks, geese, pheasants, rabbits, anhingas, squirrels, smilax, saggitaria, chestnuts, swamp lotus, prickly pear cactus, persimmons, frost grapes, muscadines, amaranth, and groundnuts.

There is no mention of bison—which is surprising, given that Huntington was talking about the old times. Her list of foods is exceedingly useful for learning how we lived of old, but it is not exhaustive. She doesn’t mention pecans or pawpaw trees. Why didn’t Huntington mention bison? She likely heard stories from people who had heard stories from people. If a story about Charlotte LeDuff’s hand gestures could get to me, I don’t see how something as interesting as bison tales wouldn’t have reached Louison Huntington. It is lost, though. Lost lost.10

A Firsthand Account

There is one known narrative of an Ishak bison hunt, by a French visitor named Louis LeClerc de Milford, who personally witnessed it. Milford traveled to Louisiana with some Creek companions in the 1780s. After visiting Vermilion Bay, he and his group made a fiveday westward march, whereupon they encountered a group of Ishak on a bison campaign, assembled after a day’s hunt. “There were one hundred and eighty of them, of both sexes, busy, as we surmised, in smoking meat.” As a guide, if we suppose Milford traversed the daily distance traveled by Lewis and Clark on a good day—approximately fourteen miles—he and his group could have traveled approximately seventy miles from Vermilion Bay. On trails, and not as the crow flies, that could possibly place them near Lake Charles, though it is uncertain exactly where they were.11

A member of the Ishak hunting party approached Milford’s group, and it turns out he was a former Jesuit missionary in Mexico (Texas is Mexico) named Joseph, who had gone Native in a big way, living with us for over a decade, becoming part of us, and fathering six children. Usually colonial documents put me in a mood, and not a good one. (Every Native who does this sort of research knows of what I speak.) However, Milford’s passage about the bison hunt gives me warm and wistful feelings in its depictions of the hunting method: the hunting party included both men and women; together, they stalked and lived near their prey until the animals were no longer suspicious; and Joseph and the assembled Ishak were friendly, shared their water, and fed the visitors smoked bison. I can see this. That is what we would do. Indigenous Peoples contribute much to Louisiana’s reputation for generosity in sharing food with strangers. Warren Perrin, scion of Acadian cultural activism in Louisiana, attributes the personal generosity of his people to interactions with Indigenous populations in the Americas. No one can visit any member of my family without being offered something to eat.12

“Their flesh serves us for food and their hides for clothing,” the former Jesuit told Milford. “I’ve been with the tribe about eleven years; I’m happy and contented and haven’t the slightest desire to return to Europe.” He was able to make that choice to live with the Ishak according to our traditional ways because there were still bison to hunt, and Ishak living the old ways. It was still possible to randomly encounter us camped together on the prairies of Southwest Louisiana, doing our thing.13

The bison hunted by the Ishak are gone, but also the bison hunting of the Ishak is gone. We can make inferences from documents and images and speculate, and we can note cultural traits of other bison-hunting Indigenous Peoples. But we cannot remember the bison hunting. It is a complete environmental loss, spanning both the animal kingdom and the realms of cultural memory. The last chance for an anecdote has passed. Not only have the wild bison of Louisiana walked on but pieces of us walked on with them.

One consolation is that bison hunts may not have been central to us in the way they were to Indigenous Peoples of the Plains. Bison were common in the Gulf South, but not as common as elsewhere. The earliest French description of a bison that we have today is a 1565 note from Nicholas Le Challeux, a member of Jean Ribaut’s doomed Huguenot colony in Florida. By the late eighteenth century, the regional bison population had waned considerably. Indigenous Nations of the Gulf South are not always culturally similar, and the traditional environments we inhabit are not interchangeable. Nevertheless, we can attempt to discern elements of our bison food traditions from evidence provided by other regional Indigenous Peoples.14

Ian Thompson’s brilliant Choctaw Food is a landmark in Indigenous scholarship of traditional foodways, combining knowledge of food preparation, acquisition, and language, with an eye not only toward documenting a tradition but also preserving it. “Although the bison has never been as central to Choctaw culture or traditional food as it is for Native American groups whose homelands are on the Great Plains,” he writes, “the bison has been important to Choctaw food in certain times and places.” He provides a traditional recipe for boiled short ribs and another for fresh meat coated in cornmeal and roasted on the ashes of a fire. Given the connection to cultures further west, I can imagine the pieces of smoked bison handed to Milford were spiced up considerably. That peppery tradition in Louisiana is Indigenous.15

Thompson notes that the Choctaw obtained materials from bison other than meat, such as bladders for carrying liquids and hides for making robes. Another colonial Louisiana image from Alexandre de Batz, the undated Sauvage en habit d’hiver, depicts a man in a bison hide robe. David I. Bushnell Jr. speculates that the man might be an Ishak, but it is unclear. Still, it provides fodder for the imagination. Perhaps Louison Huntington didn’t call to mind bison in her delineation of Ishak foods in 1885 simply because, as with the Choctaw, bison weren’t a centrally important food group to us, even if we did hunt them. The Choctaw aren’t the Ishak, though. For one, we were much more nomadic than they were, and less centralized in our societies. Perhaps it just slipped this Ishak woman’s mind to mention bison to Gatschet, or maybe not mentioning it was a quiet sort of mourning for her. Sadly, we cannot know, and that fact is indeed a loss for us Ishak.16

If we Ishak cannot access much of our historical bison hunting culture, perhaps we can create it anew. That culture would be just as Ishak as what came before, because it would be created by Ishak people, and whatever we create is Ishak culture. It is important to avoid the colonial mindset that the “real Indians” are the dead ones. It is important to avoid the mindset that our culture is static, a museum piece. In my dreams of a contemporary Ishak bison hunt, I envision us developing a contemporary bison hunting culture that is an expression of our heritage in Louisiana and Texas. As before, we could do it as a group, creating a community event.17

There are no wild bison in Louisiana, but I have seen farmed bison in Natchitoches Parish near the Adai Indian Cultural Center in Robeline, Louisiana, among other places. Bison escaped from a ranch in St. Helena Parish in 2017, causing a hunt of sorts with the remaining escapee lassoed during a chase involving two pickup trucks, a veterinarian, and some tranquilizer darts. Louisiana environmental expert Blaise Pezold has begun an online effort to restore Bison to the Kisatchie National Forest. There is a crude bit of rubble surrounded by a short fence there, the grave of one L. C. Curby, an early-nineteenth-century farmer and bison hunter who lived in the area, and who wished to be buried next to the last bison he shot, which may have been the last one shot in Louisiana, for all we know. The grave is an important monument to me, if not exactly a positive one.18

I got both packages at Costco: the ground bison and the beef ribs. The ribs fed both my imagination and my typically Louisianan love of charcuterie. The bison I cooked into some jambalaya. That’s not how my momma ‘n’ them have made jambalaya in my lifetime, but eating bison has been passed down to me through them from those assembled cousins who welcomed and fed Milford centuries ago. In my kitchen that night, the Ishak kept walking our ancient path, reminding me of what was before, and moseying forward into the next day. More than hunting, community will carry us forward as we cook together, share, tell stories, and pass them along to our descendants. When we do that, we are truly back with the ancestors on that Louisiana prairie.19

Jeffery U. Darensbourg is a Louisiana Creole and a member of the Atakapa-Ishak Nation. A 2020 resident at Tulane University’s A Studio in the Woods, his work is featured in the film Hoktiwe: Two Poems in Ishakkoy, made with Fernando López and commissioned by the Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans.

- Elizabeth N. Ellis, “The Many Ties of the Petites Nations: Relationships, Power, and Diplomacy in the Lower Mississippi Valley, 1685–1785″ (PhD diss., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2015), 17–18. For a general introduction of the tribe, its name, and its language, see Jeffery U. Darensbourg and David Kaufman, “Ishak Words: Language Renewal Prospects for a Historical Gulf Coast Tribe,” in Language in Louisiana: Community and Culture, ed. Nathalie Dajko and Shana Walton (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2019), 64–68. In a 1996 tribal reorganization, the largest group of Ishak, to which I belong, chose to use Atakapa-Ishak as a formal tribal name, as discussed by tribal member Hubert Daniel Singleton in The Indians Who Gave Us Zydeco: The Atakapa-Ishak of Southwest Louisiana and Southeast Texas, rev. ed. (Lake Charles, LA: self-pub., 2005), 30.

- Valerie Meehan, “Louisiana Tries to Improve Clams that ‘Taste like Mud,’” Washington Post, November 10, 1988.

- Richard Campanella, Bienville’s Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans (Lafayette, LA: Center for Louisiana Studies, 2008), 106; Monique Verdin, “Treading Water,” 64 Parishes, spring 2019, https://64parishes.org/treading-water. While acknowledging the existence of multiple orthographies of the language leading to variant spellings of the word “Bulbancha,” I use this version because it’s the first I learned, finding it in Chief Allen Wright’s A Chahta Leksikon: Choctaw in English Definition for the Choctaw Academies and Schools (St. Louis, MO: Presbyterian Publishing Company, 1880). On the name “Bulbancha” and its spellings, see Hali Dardar, “Bvlbancha,” 64 Parishes, fall 2019, 22. William A. Read in his 1927 Louisiana Place Names of Indian Origin (reprinted in 2008) reasons that the name was only applied to the area after colonization, assuming that linguistic diversity began with the French. William A. Read, Louisiana Place Names of Indian Origin: A Collection of Words, ed. George M. Riser (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2008), 43. Read’s assumption is flawed, as the addition of multiple European languages added slightly to the area’s linguistic diversity but did not create it. While there are other Indigenous names for the area of present-day New Orleans, they generally refer to the size or ethnic makeup of the postcolonial city, such as the Ishakkoy Nun , Uš (big village) or the Tunica Tonr wahal’ukini (white man town). Such names conform to Indigenous naming practices based on “the salient characteristics of a place, those qualities that clarify the situated identity of the place and distinguish it from other places.” Margaret Wickens Pearce, “The Last Piece Is You,” Cartographic Journal 51, no. 2 (June 2014): 108. For more on Indigenous People in Bulbancha who still use that name, listen to Laine Kaplan-Levenson, “New Orleans: 300 // Bulbancha: 3000,” December 20, 2018, in TriPod: New Orleans at 300, produced by WWNO, podcast, https://www.wwno.org/post/new-orleans-300-bulbancha-3000. Other places named after bison in Louisiana include Boeuf River, Boeuf Lake, and three separate Bayous Boeuf. George H. Lowery Jr., The Mammals of Louisiana and Its Adjacent Waters (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1974), 500.

- Robert Michael Morrissey, “Bison Algonquians: Cycles of Violence and Exploitation in the Mississippi Valley Borderlands,” Early American Studies 13, no. 2 (Spring 2015): 309–340.

- Lowery, Mammals of Louisiana, 504. The full catalog for the exhibition on Louisiana paintings may be found in Inventing Acadia: Painting and Place in Louisiana, ed. Katie A. Pfohl (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019).

- Lafcadio Hearn, “Gombo Zhèbes”: Little Dictionary of Creole Proverbs, Selected from Six Dialects (New York: Coleman, 1886), 31.

- Albert S. Gatschet and John R. Swanton, A Dictionary of the Atakapa Language Accompanied by Text Material, Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, bulletin 108 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1932).

- John R. Swanton, A Structural and Lexical Comparison of the Tunica, Chitimacha, and Atakapa Languages, Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, bulletin 68 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1919). As of June 2020, the weekly online language learning group may be found at Atakapa Ishakkoy (private group), Facebook, last accessed November 27, 2020, facebook.com/groups/371552763511458/. Other writings in Ishakkoy by Ishak poet Tanner Menard are discussed in Shane Lief and Jeffery U. Darensbourg, “Popular Music and Indigenous Languages of Louisiana,” in Proceedings of the Foundation for Endangered Languages 19 (Wales: Foundation for Endangered Languages, 2015), 142–146.

- Cyrus Byington, A Dictionary of the Choctaw Language, ed. John R. Swanton and Henry S. Halbert, Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, bulletin 46 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1915), s.vv. “camel,” “kamil.”

- There are other texts that are more contemporary than those of Gatschet. Tribal member Russell Reed has contributed stories with photographs for the aforementioned Facebook group. Ishakkoy ceremonial songs by Tanner Menard are discussed in Lief and Darensbourg, “Popular Music and Indigenous Languages,” 142–146. Contemporary Ishakkoy poetry also forms the text of the 2020 short film Hoktiwe: Two Poems in Ishakkoy by Fernando López and Jeffery U. Darensbourg, commissioned for the Make America What America Must Become exhibition at the Contemporary Arts Center New Orleans (oc20.cacno.org). One of those poems has been published: Jeffery U. Darensbourg, “Hoktiwe (for L. Rain Prud’homme-Cranford),” Transmotion 6, no. 2 (Winter 2020): 138–141. Louison Huntington categorizes the foods according to whether they were brought by colonizers (peaches, figs, apples, plums) or were native to the area (the rest). The original passage, from which I made my own translation, is found in David Kaufman, Atakapa Ishakkoy Dictionary (Chicago: Exploration Press, 2019), 148–151; and Gatschet and Swanton, Dictionary of the Atakapa Language, 9–11. I am grateful to Blaise Pezold for advice about plant references. A useful general reference when it comes to regional edible flora is Chris Bennett, Southeast Foraging: 120 Wild and Flavorful Edibles from Angelica to Wild Plums (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2015).

- Louis LeClerc de Milford, Memoir, or A Cursory Glance at My Different Travels & My Sojourn in the Creek Nation, trans. Geraldine de Courcy (Chicago: R. R. Donnelley, 1956), 60–63. The exact date of the Ishak bison hunt is unclear, but it was around the 1780s. Exact dating is especially difficult as Milford wrote his memoirs without notes and wrote about his experiences years later when he returned to France. Much about this can be gleaned from John Francis McDermott’s introduction to the Donnelley edition of the Memoir. I take the estimate for Milford’s traveled distance from “Lewis and Clark: A Missouri River Adventure,” Missouri Basin and Arkansas–Rio Grande–Texas Gulf Regions, US Bureau of Reclamation, last modified September 29, 2017, https://www.usbr.gov/gp/lewisandclark/index.html#:~:text=They%20traveled%20as%20few%20as,Lewis%20walking%20along%20the%20shore.

- Milford, Memoir, 61–62. My own attempts to pin down Joseph’s exact identity have not borne fruit so far, though the search continues. Ann N. Knake of the Jesuit Archives & Research Center in St. Louis suggests that a source of the difficulty may be the fact that the Joseph-Milford meeting took place around the time of the Holy See’s suppression of the Society of Jesus from 1773 to 1814. Ann N. Knake, email message to author, January 22, 2020. Perrin “attributes Cajun inclusiveness to the Acadians’ early and warm relationship with the Native Americans known as the Mi’kmaq, with whom the Acadians forged trading partnerships soon after settling what are now Canada’s Maritime Provinces. The Acadians intermingled through marriage with the Mi’kmaq, creating an ethnic subgroup in Canada that today calls itself the Metis (May-tee).” Walter Pierce, “Are You Really Cajun?,” Independent, October 1, 2012, http://theind.com/article-11249-are-you-really-cajun-.html.

- Milford, Memoirs, 63.

- Lowery, Mammals of Louisiana, 504; Ted Franklin Belue, The Long Hunt: Death of the Buffalo East of the Mississippi (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1996), 37.

- Ian Thompson, Choctaw Food: Remembering the Land, Rekindling Ancient Knowledge (Durant, OK: Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, 2019), 135–136, 188, 190; Jack Weatherford, Indian Givers: How the Indians of the Americas Transformed the World (New York: Fawcett, 1988), 109–110.

- David I. Bushnell Jr., Drawings by A. DeBatz in Louisiana, 1732–1735, Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 80, no. 5 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1927), 13–15.

- Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz and Dina Gilio-Whitaker, “All the Real Indians DiedOff” and 20 Other Myths about Native Americans (Boston: Beacon Press, 2016), 7–13.

- Jeremy Krail, “WATCH: Sheriff’s Office Helps Round Up Escaped Buffalo in St. Helena Parish,” WBRZ.com, November 29, 2017, https://www.wbrz.com/news/watch-sheriff-s-office-helpsround-up-escaped-buffalo-in-st-helena-parish/.

- Parts of this work were researched and composed during an Adaptations Residency at Tulane University’s A Studio in the Woods in the spring of 2020. I extend a hearty hiwew to Blaise Pezold, John DePriest, Ama Rogan, and Christine Baniewicz for advice and aid on this piece.