Art provides a powerful historical archive through which we can see our lost environmental past. In 1915, the artist Romare Bearden left the South at the age of four; decades later, he rendered evocative depictions of the southern natural world. His paintings and collages capture the lush bounty of city gardens and the women who made them grow. Cut off from the South by a northern, urban life for six decades, by the 1970s, he seemed mystified by the vegetables and flowers that sprouted from his canvases. At first, he contained them in baskets or plots, but they eventually overgrew the human figures in his work.

Fred Romare Howard Bearden, born on September 2, 1911, to Bessye and Howard Bearden in Charlotte, North Carolina, became one of the foremost American artists of the twentieth century. From a middle-class African American family, Bearden lived for his first four years in a compound of family houses in downtown Charlotte with his parents, grandmother, and great-grandparents Henry and Rosa Kennedy. The Kennedys’ Victorian home, to which Bearden returned in his imagination fifty years later, had a wrap-around porch and a garden full of flowers. At the Kennedys’ grocery store beside the house, Bearden watched urban gardeners arrive laden with produce. The Kennedys had lived there happily and successfully since 1877, but after white supremacy campaigns in the elections of 1898 and 1900, Charlotte began to strictly segregate and disenfranchise African Americans.1

The Beardens fled Charlotte in 1915 after a group of white men surrounded and threatened them on a shopping trip a few blocks away from their home. The mob mistook Romare for a white child and thought that Howard had kidnapped him. Bessye Bearden rushed back and grabbed her child, but the family heeded the warning. The Beardens left for Pittsburgh and then for Harlem, where Bessye became a leading political and cultural figure. The Great Migration, of which the Beardens were a part, represented opportunity, but it came at the expense of losing home.2

During the course of his career as an artist, Bearden moved from Cubism and Social Realism in the 1930s to abstract art in the 1940s and 1950s, before he seriously took up collage in 1961. He won great acclaim for his “collage paintings” from the 1970s until his death in 1988. The southern landscape became a recurring theme in those later works. Bearden spent decades trying to remember that time when he was a beloved child who belonged in Charlotte, living with the Kennedy family, nestled in safety and basking in love. He called that past and that place “a homeland of my imagination.”3

He called that past and that place “a homeland of my imagination.”

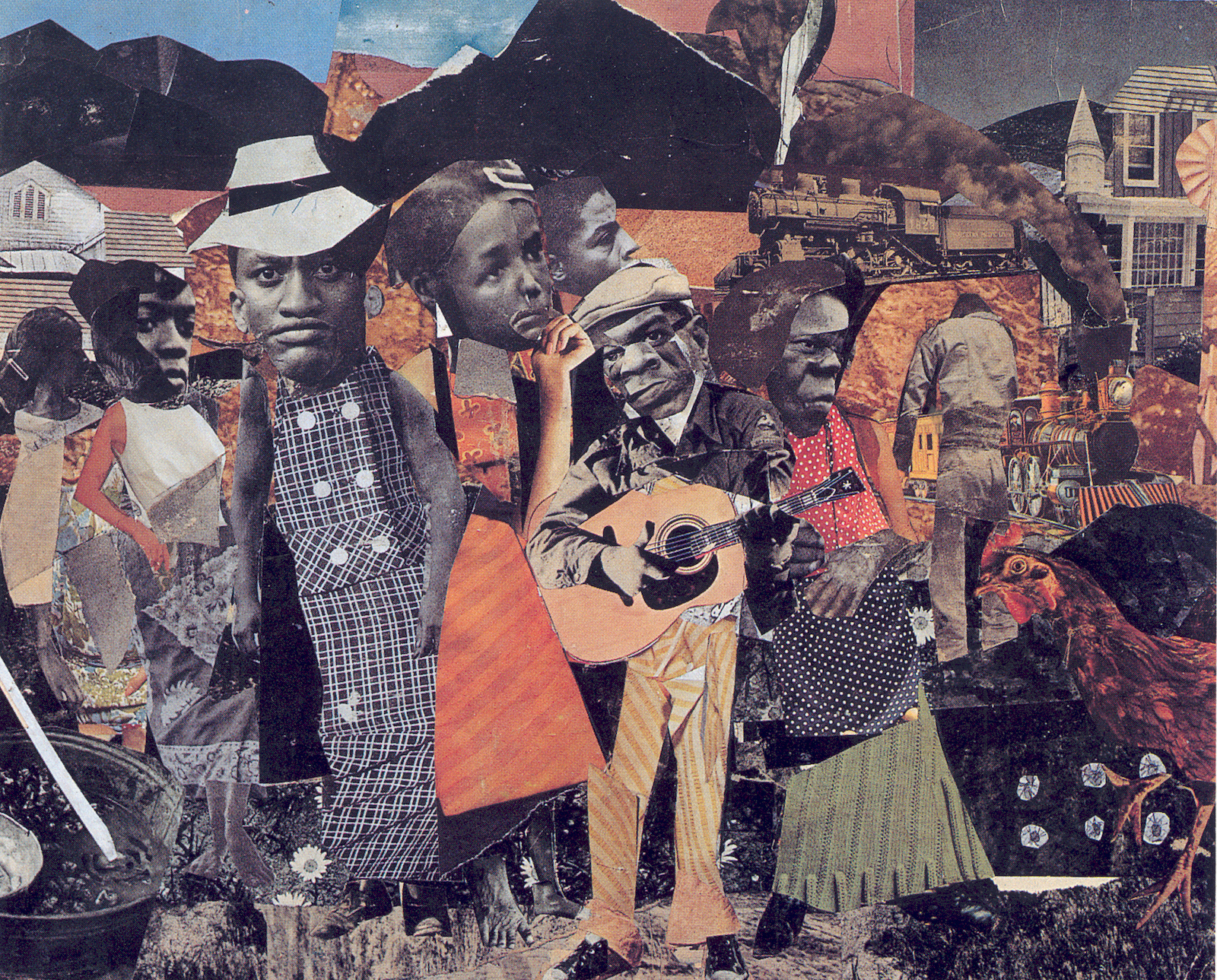

His turn to collage in the early 1960s, after more than a decade of pursuing abstract art, became a turn back to the South as well. A founding member of Spiral, a Black art collective in Harlem, Bearden began to work on a series with southern themes in 1974, with seventeen collages titled Of the Blues. His Mecklenburg County, Saturday Night (1974) marked a homecoming for him. Incomplete memories of his early childhood in Charlotte haunted him and he used them to depict the people and environment of the South. “Most artists take some place, and like a flower, they sink roots, looking for universal implications. … My roots are in North Carolina.” In his work, Bearden explored time’s circularity, revisiting and reinventing the past, and return visits to the South in the late 1970s refreshed his recall.4

As an old man, Bearden saw gardens with a child’s eye, from a memory so deep that it was nearly buried. Bearden did not expect to traffic in “full” memories—their wispiness was part of his artistic experience. “Well, the memories are just there,” he said. “Sometimes,” he conceded, “you have to surrender something.” But often enough, he “stayed with it, and finally it came through.” Bearden understood his work to be like that of Édouard Manet, whom he quoted as saying, “A painting isn’t finished; sometimes you get on the surface.” Bearden willed himself to dig deep into the past, consciously and unconsciously, until a complex southern landscape surfaced from Bearden’s red clay. Charlotte’s quotidian natural world had given him his first intimation of beauty; it came to ground his artistic aesthetic. The writer Ralph Ellison described Bearden’s work as a “telescoping of time.”5

You know, it’s good earth here; it’ll be here again.

For example, a sixty-five-year-old memory of one bloom transported him back to his last visit to his great-grandparents’ Victorian home at 401 Graham Street and the grocery they owned nearby. “I must have been ten, nine or ten years old, and I was in Charlotte. And my great-grandfather had a garden in front of his house and there were flowers,” he recalled. “I was struck by this one flower because it was so beautiful to me; it seemed to me it was an unusual, beautiful flower. They told me it was a tiger lily. I would look at this lily every day when I was down there. And one day the lily was gone. And I couldn’t understand it. There was nothing but a green stem, and this beautiful flower was gone. My grandfather had cut it to give to my great-grandmother to wear to church.” He continued, “I still remember how I was so disheartened at seeing that flower gone. He told me, ‘Well, when you come back next summer it’ll be here again.’ He said, ‘You know, it’s good earth here; it’ll be here again.’”6

At the turn of the twentieth century, emerging New South cities incorporated the rural environment in their midst. Residents, often newly transplanted from rural communities, could not imagine a city without flowers, vegetable gardens, chickens, and the occasional pig. This was especially true for African Americans, for whom self-sufficiency and independence were rooted in growing their own food. These urban farmers consumed most of what they grew and sold the rest to small stores like the Kennedys’ grocery.

Well into the 1930s, small-scale farming appeared more often in dense urban spaces than in the new planned suburbs that ringed cities. For example, Dilworth, the first streetcar suburb in Charlotte, lay three miles west of the Kennedy home. Begun in 1891, it seemed that the project included Black citizens, albeit on separate streets named Congo, Stanley, Livingstone, and Zanzibar. But those were never developed and, by 1912, the Olmstead Brothers’ landscape architectural firm had laid out curved streets and smaller lots in Dilworth that would begin a process that reduced city farms first to garden plots and then quickly to two-car garages and landscaped lawns.7

For four summers, Bearden came to consciousness in a city that blended industry, commerce, and farming. His 1964 collage, Watching the Good Trains Go By, depicts his view from the Kennedys’ porch and captures the cacophony of what urban people began to call “country come to town.” Amid all the modernity that the trains brought, Bearden includes the domesticity of the yard—morning glories and daisies in a jug, the old rooster that chased him around, and the cast iron kettle in which women washed clothes and made lye soap. The young women are barefoot, as many young southerners often were. Within the work, Bearden uses the universal language of nature to embed an homage to Paul Cézanne. The low Piedmont hills visible from Graham Street have changed shape to become Mont Sainte-Victoire, with its sheer peak and ever-changing shadows, which Cézanne painted countless times from his rustic studio above Aix-en-Provence. Bearden is telling us, as Cézanne did, that you can stand in your own front yard and see the world.8

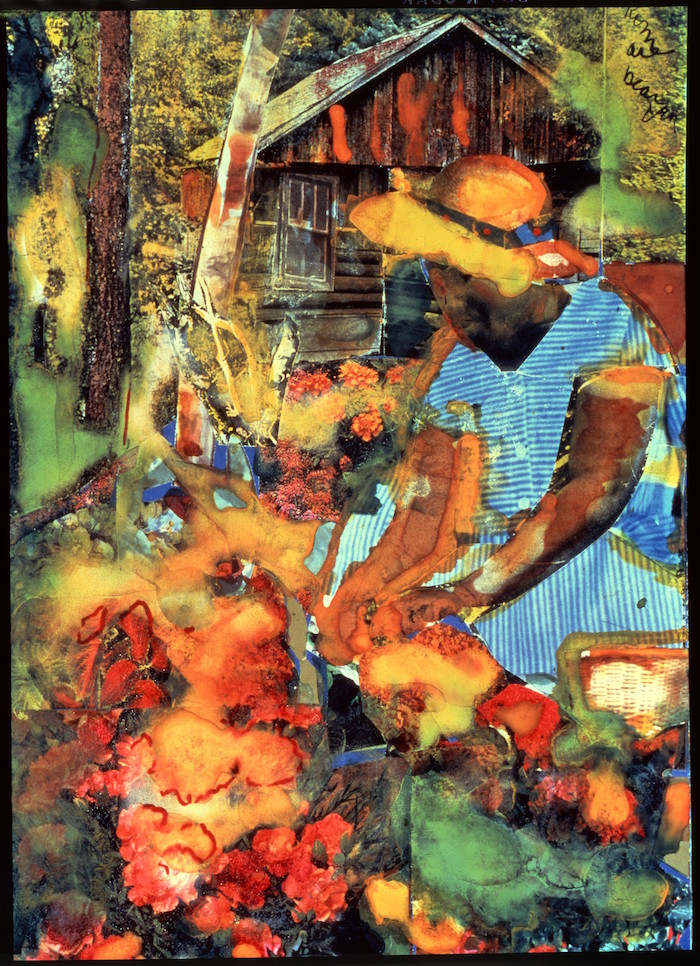

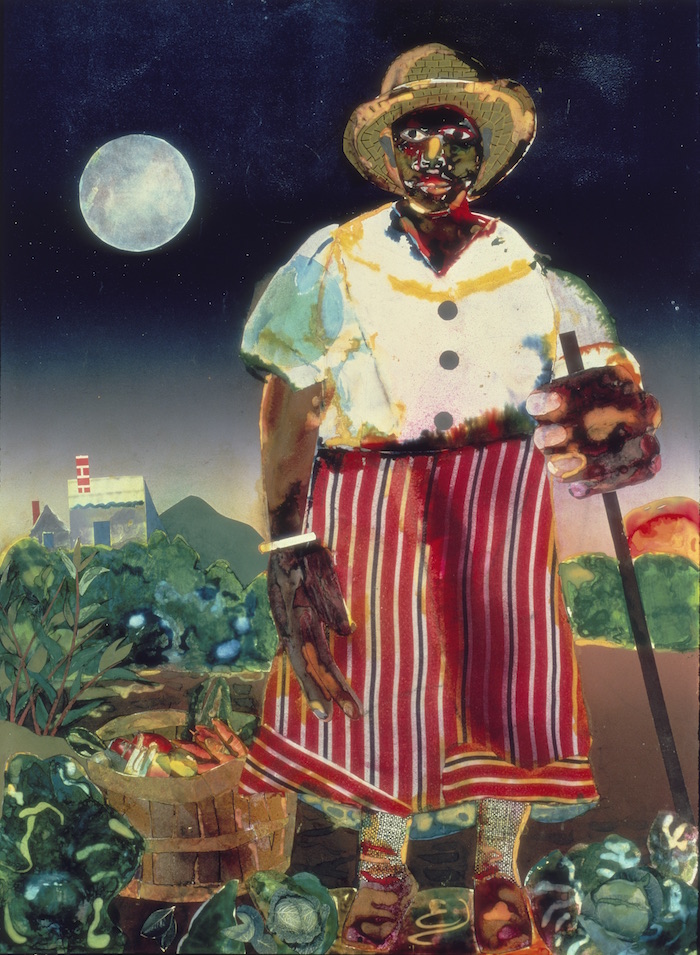

Bearden painted several canvases of the garden of a Charlotte neighbor, whom he called Maudell Sleet. He recalled, “She had a garden, when I passed she was always giving me something. . . . She was a very nice lady. Very powerful woman. And she kinda symbolized, you know, the earth, someone with an intimate relationship to it in many ways . . . people who can grow things.” On another occasion, he recalled, “She had a green thumb, [and] she kept a small farm going by herself after her husband died. When I passed as a boy, she would say, ‘Well, here’s some blackberries or blueberries; take it to your grandmother,’ or ‘Here’s some flowers.’” He continued, “I can still smell the flowers she used to give us and still taste the blackberries.” He first recalled Maudell Sleet in 1978, when he was sixty-seven, with the works Profile/Part I, The Twenties: Sunset and Moonrise with Maudell Sleet and Maudell Sleet’s Magic Garden in the same series. He created another, simply titled Maudell Sleet, sometime around 1980, and finished five years later with a fourth, Summer (Maudell Sleet’s July Garden).9

Before Charlotte entombed itself in pavement and encircled that tomb with interstate highways, there was something called the cool of the evening. After supper, but before the dew fell, women would go to their gardens with hats, hoes, and bushel baskets. The moon often rose as the sun set, so you could still see to work. It was the bug hour. In Sunset and Moonrise with Maudell Sleet, she is wearing men’s brogans on her feet, as many women did when they worked the ground. The middy blouse she wears was fashionable in the 1910s, and her skirt is an apron. Country-come-to-town white women often wore old-fashioned sun bonnets in their gardens, while Black women typically wore straw hats.

Maudell Sleet’s hands are enormous, a common occurrence in Bearden’s collages. As Bearden stated, “I want to express the handness of hands,” by which he meant their capabilities, their importance. He thought with his hands. “Whatever intelligence you have gets into your hand,” he said. Sleet’s hands are big enough to hoe, to farm, to do a man’s work. On the farm, cultivation might be a man’s job, but it was the women, white and Black, who kept city gardens. Urban men rarely did this men’s work. Maudell Sleet is built like a man. She has no airs, no graces; she doesn’t mess with much foolishness. She makes vegetables come out of the earth. To Bearden, this was magic.10

The bushel basket has plaited wire handles on each side, and its slats curve to come together at the bottom. These baskets brought vegetables in from the garden and home from the store. Turned upside down, they would seat a child. When the bottom burst open after years of use, they went to their reward as basketball hoops. They scattered along the roads of the South just as plastic bags now tangle up in trees. Sleet’s bushel basket is filled with carrots, tomatoes, leeks, and cucumbers—those little cucumbers that are sweet. Bearden seems in awe of her power, which turns supernatural as the cabbages and collard greens surrounding her become phantasmagorical creatures.

Of Sleet, Bearden said, “I’ve done her about two or three times; and each time the facial characteristics are different: I wouldn’t recognize her as the same woman one for the other, but it’s all right for my memory, because I’m recalling this thing.” Recalling, asking that something or someone return to mind, isn’t the same thing as remembering. He explained, “I paint out of the traditions of the blues. You start with a theme, then you call and recall it.” In the African American blues tradition of call and response, incorporated in jazz, Bearden didn’t just try to remember what happened; rather, he called out to see if the past would answer. One time, the past answered with a name: Maudell Sleet.11

“I paint out of the traditions of the blues. You start with a theme, then you call and recall it.”

Like Bearden, Sleet was an artist. Unlike Bearden, her work vanished annually. She began anew each spring. In her essay “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens,” Alice Walker writes of Black women, “They were Creators, who lived lives of spiritual waste, because they were so rich in spirituality—which is the Basis of Art.” And of her own mother, she said, “Whatever she planted grew as if by magic. … Because of her creativity with her flowers, even my memories of poverty are seen through a screen of blooms.” Millions of southern women, Black and white, created their masterpieces in southern cities every year until, sometime in living memory, their environment vanished. Landscape architects, zoning officials, and city planners redrew cities and obliterated their work.12

Along with their gardens, these women vanished from the historical record. Bearden could not actually figure out who Sleet was, although he tried hard to remember her. She must have been a neighbor of the Kennedys on Graham Street, because he came to think that she had a husband: “He was a nice man. When he drove by, he would sometimes call me over and say, ‘Here.’ He’d give me some candy or give me two cents. … And he died before Ms. Sleet, and so she had to run the farm, the whole thing by herself.” On another occasion, he said that Mr. Sleet became a ghost and haunted the place after his death. There is no record of anyone named Maudell Sleet ever living in Charlotte. Or anywhere.13

For years I have searched for Bearden’s garden’s mother, even as I questioned whether finding her mattered at all. There are, most often, two main characters in environmental history: the environment itself and the forces that destroy it. Less often do we see the people who tend and sustain it, even though their work inspires great art and literature. When William Wordsworth “wandered lonely as a cloud” only to find comfort in “a host of golden daffodils,” he gave no thought, at least in the record, to the person who might have planted the first bulbs. When we do see small farmers in the historical literature, we most often rely on statistical composite profiles. And when we think about the environment and climate change, it’s difficult to imagine that one person’s practices can make any difference. As long as individual actions seem hopeless, a sort of catatonic apathy takes hold. I’ve looked so long for Maudell Sleet because she did make a difference. She produced the beauty that inspired art.14

No one named Maudell Sleet ever came to be recorded in any official document, but there was a woman named Maude Slade who lived two blocks down Graham Street from the Kennedy/Bearden home. It was likely her name, mangled by memory, that came to Bearden so many decades after her garden vanished. Born Maude Morgan, she grew up on her grandparents’ farm thirty miles from Charlotte. Upon finding herself pregnant at fifteen, she married Walter Slade in 1908. By 1910, seventeen-year-old Maude Slade lived at 607 South Graham Street with her husband Walter and his parents Celia and Edward Slade, a barber born in slavery. But while Maude Slade’s name came to Bearden, it was likely forty-six-year-old Celia Slade’s body that he remembered as the older, powerful woman, even as Celia put her young farm girl daughter-in-law to work in the garden. Walter Slade, who was legally blind, taught music and played the piano at the segregated Black movie theater. Maude’s daughter Arrahwanna was two years older than Bearden. These facts obscure as much as they illuminate.15

But this headline appeared in the Charlotte News on March 7, 1911: “Blind Negro Was a Gay Othello.” When Maude came upon Walter one evening “escorting” another woman home in a hack, a fracas ensued. When the other woman tried to jab Maude with a hat pin, Maude called the police and told them that Walter had assaulted her with a pistol and carried a concealed weapon. In court, Walter argued that he had not pointed his gun at Maude and, anyway, it wasn’t concealed. The white newspaper smugly reported, “When it was all over they were shooed out of court.” This sort of publicity would have scandalized Bearden’s great-grandmother and grandmother, the president of the local Black chapter of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union.16

Walter and his parents left for Washington, DC, sometime in the mid-1910s, but Maude did not go with them. If she stayed in their house, Celia’s garden would have become hers, and Bearden’s family might have referred to the deserted woman in hushed tones. They may have talked about Walter as Maude’s “ghost husband,” a common term at the time for a legally married man who had deserted his wife. In Washington, Edward became a successful barber again. Walter beat out Duke Ellington in a jazz performance contest and, by 1920, eleven-year-old Arrahwanna lived with them. Some years later, Maude and Walter patched up their marriage, and Maude moved to Washington, where she lived with the Slade family and worked as a maid in a hotel. If one wrote a biography of Maude Slade, as art historians do, it would resonate with the metahistory of African American life in the first half of the twentieth century.17

It was simply things growing. That was Maudell Sleet.

In his last Maudell Sleet work, Summer (Maudell Sleet’s July Garden), Sleet vanished. There are smooth brown stones where the woman might have been. Flowers, fruits, bugs, and birds have taken over. Two tiger lilies burst forth. The flora seems sinister yet beckoning, too colorful to bear, and alive in a way that plants just shouldn’t be. They might eat you up if you looked too long. Bearden’s biographer and oral historian, Myron Schwartzman, exclaimed to him, “The last time we saw Maudell Sleet, she wasn’t in the collage, she wasn’t even in the collage! It was simply things growing.” Bearden replied, “That was Maudell Sleet.” Perhaps that is the best requiem for the unseen artist.18

The lush colors recall those of tropical St. Martin, where Bearden spent part of each winter in later life, more than they recall Charlotte. All of Bearden’s own artistic history is represented here: rectangular Cubist forms, the use of color to impose shapes, the dark lines reminiscent of those that his teacher George Grosz drew. Bearden was dying of bone cancer, and his exhaustion shows through the papers, paint, and ink with the surface abrasions and bleached spaces. It is as if Bearden is recalling Charlotte at the same time that he is celebrating the ethereal and timeless aesthetic of nature.

Bearden once said of Charlotte’s landscape, “All this is gone, and the people are gone, and the people who thought that way are gone.” Today, Maude Slade’s garden lies under the thirty-three-acre Bank of America Stadium, and Bearden’s great-grandparents’ home is a vacant lot beside the Charlotte Panthers’ parking deck. Nearby is Romare Bearden Park, a five-acre, “$10 million signature urban park,” according to its designers, who tell us, “Authentic urban experiences matter.” In one corner is a little plot with a raised flower bed named “Maudell’s Garden.”19

Despite the erasures—despite everything that is gone—Bearden’s art allows us to reclaim it, if only in the homelands of our imaginations. As for me, I’m convinced that one Sunday afternoon, while watching a Panthers’ game, I’ll see a squash vine sprout on the fifty-yard line. And it will grow magically, monstrously, until it covers the field.

This essay first appeared in the Human/Nature issue (vol. 27, no. 1: Spring 2021), now available for order.

Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore is the Peter V. and C. Vann Woodward Professor of History Emerita at Yale University. She coauthored, with Thomas J. Sugrue, These United States: A Nation in the Making, 1890 to the Present. Previous works include Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896–1920 and Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights, 1919–1950. She is completing Romare Bearden and the Homeland of His Imagination, to be published by UNC Press.NOTES

- C. H. Watson, ed., Colored Charlotte Souvenir: The Fiftieth Anniversary of Freedom of the Negro, Charlotte, North Carolina, 1915 (Charlotte, NC: A. M. E. Zion Job Print, 1915), 7; Richard Maschal, “Acclaimed American Artist Celebrates His Charlotte Roots,” Charlotte Observer, October 5, 1980, F1, 4, 5; Sanborne Maps, Charlotte, North Carolina 1911, sheet 13, microfilm, Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Charlotte Mecklenburg Library, Charlotte, North Carolina; Charlotte City Directories, 1910–1915, accessed on Ancestry.com; Myron Schwartzman, Romare Bearden: His Life and Art (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1990), 13–14. On Charlotte’s Black middle class, see Janette Thomas Greenwood, Bittersweet Legacy: The Black and White “Better Classes” in Charlotte, 1850–1910 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994); Thomas W. Hanchett, Sorting Out the New South City: Race, Class, and Urban Development in Charlotte, 1875–1975, 2nd ed. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020); and Patricia Ryckman Randolph, An African American Album: The Black Experience in Charlotte and Mecklenburg County (Charlotte, NC: Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County, 1992).

- Stephen Kinzer, “Charlotte Exhibit Honors Master of Collage,” New York Times, reprinted in News and Observer, October 6, 2002, clipping in the North Carolina Collection Clipping file, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Schwartzman, Romare Bearden, 18. Bearden’s first collage was Harlequin in 1955, composed with paint and paper, an homage to Picasso’s painting of the same name. Circus: The Artists Center Ring (1961) appears to have been his first using only paper. After eighteen months at Boston University in fine arts, Bearden graduated from New York University with a BA in math education. Next, he studied at the New York Art Students’ League with George Grosz, who experimented with collage in the 1910s and 1920s in Germany and France. For readers seeking an introduction to Bearden’s life and work, biographies include Schwartzman, Romare Bearden; and Mary Schmidt Campbell, An American Odyssey: The Life and Work of Romare Bearden (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018). On aspects of his artistic career, see Robert G. O’Meally, ed., The Romare Bearden Reader (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019); Robert G. O’Meally, Romare Bearden: A Black Odyssey (New York: DC Moore Gallery, 2008); Richard J. Powell, Margaret Ellen Di Giulio, Alicia Garcia, Victoria Trout, and Christine Wang, Conjuring Bearden (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006); Mary L. Corlett, Leslie King-Hammond, Jae Emerling, Carla M. Hanzal, and Glenda Gilmore, Romare Bearden: Southern Recollections (Charlotte, NC: Mint Museum; London: Giles, 2011); David Driskell, Two Centuries of Black American Art (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1976); M. Bunch Washington, The Art of Romare Bearden, The Prevalence of Ritual (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1973); and Ruth E. Fine, The Art of Romare Bearden (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2003).

- Romare Bearden, interview by Avis Berman, July 31, 1980, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; Romare Bearden, “I Paint Out of the Tradition of the Blues,” interview by Avis Berman, Art News 79 (December 1980): 62; Bearden quoted in Julia Markus, “The Art of Romare Bearden Returns South with Collages Reminiscent of His Native Charlotte, Harlem and Pittsburgh,” Smithsonian, March 1982, 70–77.

- Lisa Gail Collins, “A Child’s Eye, An Artists Mind, and a Man’s Heart: Romare Bearden’s ‘Profile/Part I: The Twenties,’ Series,” Masters of African American Art, an Online Journal by Professional Scholars Grant Recipients, Anyone Can Fly Blog, http://acffessay.blogspot.com/, accessed January 7, 2021; Schwartzman, Romare Bearden, 35, 38; Bearden to Walter Quirt, quoted in Kymberly N. Pinder, “Deep Waters: Rebirth, Transcendence, and Abstraction in Romare Bearden’s Passion of Christ,” in Ruth Fine and Jacqueline Francis, eds., Romare Bearden, American Modernist (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2011), 146; Ralph Ellison, “The Art of Romare Bearden,” Massachusetts Review 18, no. 4 (Winter 1977): 680.

- Romare Bearden, interview by Henri Ghent, June 29, 1968, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. The Beardens likely visited the Kennedys in 1920 after living in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, Canada. After police arrested Howard Bearden for vagrancy, he packed the family up the next morning and vowed never to return to Charlotte again. Schwartzman, Romare Bearden, 17.

- “Dilworth Historic District,” National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form, United States Department of the Interior National Park Service,1, accessed June 10, 2020, https://files.nc.gov/ncdcr/nr/MK0127.pdf. On the remaking of Charlotte residential neighborhoods and Dilworth, see Hanchett, Sorting Out the New South City, loc. 1569–1585 of 9176 and chap. 6, Kindle.

- Ruth Fine notes the resemblance of Paradise Peak on St. Martin, where Bearden had a second home, to Mont Sainte-Victoire. Fine, The Art of Romare Bearden, 85, 87.

- Romare Bearden, interview by Myron Schwartzman, interview AR2013.18.3.2_01_A, Mint Museum Library, Charlotte, NC (hereafter cited as Schwartzman tapes); Markus, “Romare Bearden Returns South,” 74; Schwartzman, Romare Bearden, 159.

- Romare Bearden, interview by Esther Rolick, [1963?], Esther Rolick Collection, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; Calvin Tomkins, “The Intelligent Hand,” in Romare Bearden: Mecklenburg Autumn, November 12–December 17, 1983 (New York: Cordier and Ekstrom, 1983), n.p. See Jacqueline Francis, “Bearden’s Hands,” in Romare Bearden, American Modernist, eds. Ruth Fine and Jacqueline Francis (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2011), 121. For an overview of southern women and farming in the period, see Lu Ann Jones, Mama Learned Us to Work: Farm Women in the New South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002).

- Schwartzman, Romare Bearden, 33; Bearden’s blues quote from Romare Bearden, interview by Avis Berman, July 31, 1980, Romare Bearden Papers, 1937–1982, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. For Bearden on the connections between his art and music, see Ben Wolf, “Abstract Artists Pay Homage to Jazz,” Art Digest, December 1946, 15; Nelson Breen, ed., “To Hear Another Language: Alvin Ailey, James Baldwin, Romare Bearden, and Albert Murray in Conversation,” Callaloo 40 (Summer 1989): 431–452; Joy Peters, “Romare Bearden: Jazz Intervals,” Art Papers 7 (January–February 1983): 11; and Romare Bearden, “Reminiscences,” Riffs and Takes: Music in the Art of Romare Bearden (Raleigh: North Carolina Museum of Art, 1988). In addition to his art, Bearden wrote or cowrote the lyrics to some twenty songs.

- Alice Walker, “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens” in Angelyn Mitchell, ed., Within the Circle: An Anthology of African American Literary Criticism from the Harlem Renaissance to the Present (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1994), 403–408. Collins’s piece “A Child’s Eye” invokes Alice Walker’s essay in discussing Maudell Sleet. Collins, “A Child’s Eye,” 2–3.

- Romare Bearden, “‘Inscription at the City of Brass’: An Interview with Romare Bearden,” interview by Charles H. Rowell, Calloloo 36 (Summer 1988): 440; Schwartzman, Romare Bearden, 159; Schwartzman tapes.

- William Wordsworth, “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud,” Poetry Foundation, accessed December 10, 2020, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45521/i-wandered-lonely-as-a-cloud; Margaret Ellen Di Giulio, “Memory, Mysticism, and Maudell Sleet,” in Conjuring Bearden, eds. Richard J. Powell, Margaret Ellen Di Giulio, Alicia Garcia, Victoria Trout, and Christine Wang (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), 50.

- Maude Slade, Walter Slade, 607 South Graham Street, Charlotte, Charlotte, North Carolina City Directory 1909, 1910, 1911, US City Directories, 1822–1995, Ancestry.com; Walter, Edgar [sic], and Celia Slade, US Federal Census 1900, Ancestry.com; Maude Morgan, Clear Creek Township, Mecklenburg County, US Federal Census 1900, Ancestry.com. There is one outside contender for the role of Maudell Sleet. Henry Kennedy may have regularly taken Bearden out to the edge of town where a young woman named O. Maud Bell and her sister Mozelle worked on her father’s “home farm,” to buy produce for his store. Of course, Bearden may have amalgamated his memories of their farm on Providence Road with Maude Slade’s urban garden down the street from him. US Census, 1910, 1920, Cyrus Bell, O. Maude Bell, Providence Road, Charlotte, NC, US Federal Census, 1910 and 1920, Ancestry.com. “Arrah Wanna” was the title of a 1909 hit song about an “Indian maid.” “ARRAH WANNA by Arthur Collins & Byron G. Harlan 1909,” cdbpdx, July 23, 2015, YouTube video, 3:35, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m8gr7KEuZeM.

- “Blind Negro Was a Gay Othello,” Charlotte News, March 7, 1911, 8.

- Walter, Arrahwanna, Celia, and Edward Slade, US Federal Census 1920, Ancestry Library Edition; Edward Slade, Barber, Washington, DC, 1920, US City Directories, 1822–1995, Ancestry.com; Mrs. Maude Slade, Washington, DC, 1929, US City Directories, 1822–1995, Ancestry.com; Maude Slade, US Federal Census 1930, Ancestry.com.

- Summer (Maudell Sleet’s July Garden) reproduced in Fine, The Art of Romare Bearden, 116, no. 125; Schwartzman tapes.

- Interview with Bearden found in Schwartzman, Romare Bearden, 42; “2016 Romare Bearden Park Charlotte North Carolina,” LandDesign, accessed December 10, 2020, https://www.landdesign.com/project/romare-bearden-park/; “Romare Bearden Park Under Construction,” Charlotte City Center, November 1, 2012, https://www.charlottecentercity.org/romare-bearden-park-is-under-construction/.