Jackie Shane is not an easy person to interview. She was one of the greatest soul artists of the 1960s. (“The greatest singer who ever lived,” says Skippy White, dean of the Boston soul scene over the last half century or so.) Designated male at birth in Nashville in 1940, she openly began to identify as female as a preadolescent, and quickly established her own fluid identity, evolving into a no-nonsense, fuck-you-pay-me stage presence that remains shocking well over a half century later. It could not have been easy. As she says in the middle of her most famous recorded mid-song monologue, from “Money (That’s What I Want),” recorded at the Saphire Tavern in 1967, “It’s fatiguing being a Jackie Shane.” Throughout her career, Shane was likened to Little Richard, a comparison she dismisses with varying degrees of humor and disgust depending on her mood. In reality, her combination of raw vocal talent, wit, glamor, and overall mystique is without comparison. (“I wasn’t to have siblings. What could you bring forth after me?”)

I wasn’t to have siblings. What could you bring forth after me?

Shane found a career and relatively safe haven in Toronto. The acceptance she was shown there was a revelation, and Jackie considers the city home to this day. For a variety of reasons best summed up in the voluminous yet tantalizingly incomplete liner notes to the recent collection of her work, Any Other Way, Shane left the business in 1971. She settled first in Los Angeles with her mother, Jessie. They moved to Nashville in the late ’70s or early ’80s, and Shane has lived there since. (Jessie Shane passed in 1997.) Over the years, Jackie’s legend grew and rumors proliferated. Many said she was dead; some said she’d been murdered. All attempts by writers and fans to make contact were met with dismissal until shortly after the CBC ran a radio documentary by Elaine Banks entitled I Got Mine: The Story of Jackie Shane, in 2010. A British listener named Jeremy Pender heard the program and felt inspired to strike up a telephone friendship with Shane, whom he’d seen perform in Toronto in the late ’60s. I learned the gist of her story in 2013, and thanks to Pender managed to wrangle an introduction in early 2014. Although we’ve spoken on the phone at least weekly since then, I’ve still never met Jackie, and wonder if I ever will. When I arrived at her doorstep in the summer of 2016 with a contract on behalf of the Numero Group record label based in Chicago, she wouldn’t come to the door or window, and scolded me for the invasion of her privacy. (Revisiting my notes for this article, I’m reminded that I found and returned a lost pair of her eyeglasses in the tall grass.) But she did sign, and this most challenging of projects, entitled Any Other Way after Jackie’s biggest hit, came to fruition in late 2017.

Jackie hates interviews but loves to talk. Apart from conversations leading to the liner notes, she has agreed to just seven interviews to date, starting with the New York Times, and most recently made her first radio appearance on Sveriges Radio (Sweden Public Radio)—after passing on an opportunity to speak with Terry Gross for Fresh Air. We decided that the easiest thing would be to look at and discuss photos from the liner notes. The following interview is condensed and edited from approximately three hours of concentrated discussion, along with another four or so of digression, argument, pleading, and laughter.

Douglas Mcgowan: Let’s start with the cover of the album (above). As you know, we engaged in a little digital trickery here to move the poster down behind your head because it reads “Shayne” instead of “Shane” because we didn’t want to confuse people with that misspelling.

Jackie Shane: It’s not a poster, it’s a painting. I commissioned it to have something to look at at home. It’s right here in my living room.

DM: What’s going on in this photo?

JS: That’s in Nashville, just a casual evening. Mom wanted to take some pictures, and she did. And that was that. I was on the chaise lounge, and mom took the picture. It was summer. It was just an evening at home, in my room.

DM: Were you actually smoking?

JS: Yes, but I never inhaled. I had got to the point where holding something in my hands steadied me. Like worry beads. I never liked the taste of smoke, but I was burning up two cartons a month. But I decided it was time to stop, so I stopped. I never do anything I can’t control.

DM: When did you stop?

JS: Four years ago. [Further questioning reveals that it was probably closer to sometime around the turn of the century.] I wasn’t all dressed up—it was just me walking about, or sitting about—it’s just a plain shirt dress. It’s not like I was going out and wanted to look a certain way. This is just around the house.

DM: But you wouldn’t go out and walk to downtown Nashville looking like this—

JS: I don’t have any restrictions on me. I’ve never had a problem there. I am what I am. I don’t have to add or subtract anything. It’s just, “Yes ma’am, no ma’am.” You would know if you met me. I’m not like anyone else. It’s always, “Yes ma’am, no ma’am.” I can wear anything I want. It’s very natural because that’s the way I was born.

I am what I am. I don’t have to add or subtract anything. It’s just, ‘Yes ma’am, no ma’am.’

JS: This was the Jerry Jackson Revue (above). They’re entertainers and musicians and oh . . . Good lord. The boys, that was a singing group, the girls are in a chorus line. TV Mama isn’t here—they called her that because she was big and fat. She stripped. But she isn’t here. Carboo isn’t here. That was the snake dancer. We picked up more people as we went along, and this must be before we got to her. I don’t like snakes—those that slither and those that walk on two legs. Carboo would take her snake—a big boa constrictor—for a walk, like a dog. The man at the far left is Iron Jaw. He chewed glass. He said that he could pick a table up with his mouth. He said that he could lift a table with a woman and a goat on it—with his mouth. He would be at the club, and point at someone’s glass, and say he wanted it. And there was Millicent; she was six years old and did a striptease. She’s not here either.

DM: I’m curious about the large woman on the left.

JS: Rose—Rose was a guy. She was six feet one. When she got made up she was quite beautiful.

DM: Where is Jerry Jackson in this picture?

JS: He’s not in the picture either. He was the manager. He told me that I would learn—after all, I was young—show business. How many children would not want to travel with the carnival? I like to experience things. Reading about it would do nothing. Being a part of it just thrills me.

DM: You look like you’re wearing a lot of makeup here.

JS: Not really, just the eyebrows.

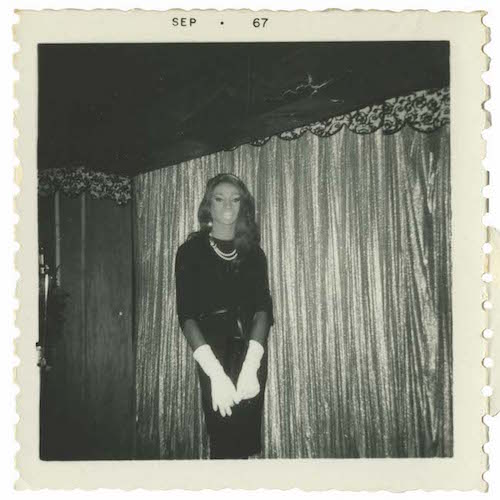

JS: These pictures are simply pictures (above). They’re poses. People forget. I’m doing my thing. This is me, I present myself, and I go about my business. That’s all. There’s nothing I was trying to prove. Like everyone else, I’m just going about my life, that’s all. Now, what you want to put onto it, and add to it, that’s your thing.

JS: This one, little miss thing (right). That was for Mother’s Day. If she was still alive, you wore a red one. If she was passed, you wore white.

DM: How old were you here?

JS: I would say [long pause] five or six years old.

DM: You’re very dressed up here.

JS: Oh yes, I didn’t look like that every day. When we were in school, it wasn’t like it is today. The teachers were well dressed, to show us how we wanted to look when we grew up.

DM: You’re dressed here in a little boy’s suit.

JS: I don’t look at things like other people do—I wear what I please. I do what pleases me. I’m still Jackie—nothing changes.

DM: Were you a rebellious child?

JS: No. I wasn’t fresh, I wasn’t familiar. Just intelligent. I listened. I listened to my elders, I got a great deal from them. I wanted knowledge.

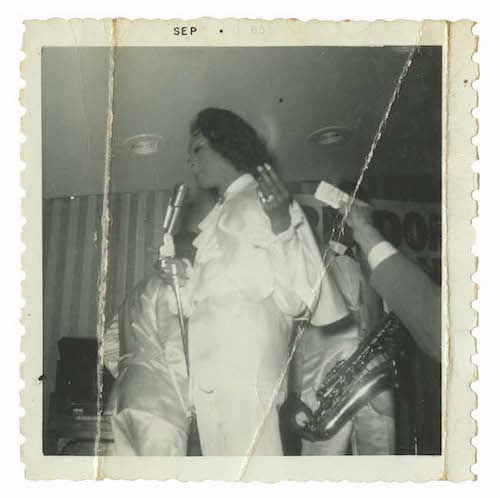

JS: That’s a cape suit, with ruffles, silk (above). Very classy. This is at the Brass Rail on Yonge Street. Guys giving me money, and I loved to accept it.

DM: Do you think you were singing “Money” here?

JS: I was probably dialoguing.

DM: So did you actually fashion your rap to motivate people to give you money in the middle of the song?

JS: Sure! I would say it—give me diamonds, give me furs, give me beautiful things—but don’t give me problems. You may think it’s playful, but I’m not playing. Get up off of it. I don’t believe in Christmas, but I believe in gifts every day. A friend of mine said, “Girl, at one time, I didn’t even think you were human.” Guys respect women who are forceful. This is how it is.

I remember at this club, one night, they had a table there by the side of the stage, and there were two guys there, and they were ready to get down and dirty. I noticed them, and I looked at them, and I didn’t take my eyes off of them. I don’t play. Frank called me up. As I went, I kept looking at them, and I kept my eyes on them, daring them to move, as if to say, “If you try anything, I will kill you.” And I went up on the stage and did what I do. They left soon after.

JS: When I found out that Dr. King was a legitimate, caring person, I said, “What can I do to help this, this is very important” (above). I decided I couldn’t sit in, because if someone pours food or something on me, I’m going to rip your throat out. So what could I do? I said, I’ll raise money and send it to them.

DM: What did the rest of the band feel about it?

JS: They felt good. You see, evil thrives in the shadows, but once you put a light on it, people know. We had to put a stop to it, and we did.

DM: So what is the cause today?

JS: What is the cause today? What can be. If the people want it. As Christ said, I didn’t come here to solve your problems, you must do that. If you want things to change, you must change them.

I’ve never voted, and I never would. This is how I look at it. It’s like a barrel. And everything in the barrel is polluted. And whatever you put into the barrel is going to be polluted too. And until you throw the whole thing out, and then until you’re very careful about what goes into it going forward, it’s still going to be crooked.

I believe things because I come from a group who have gifts—African people. Look at Egypt. How did they do it? How do you lift those stones without machines? And put them exactly—you couldn’t put a straw between them—how do you do that? There are things that you’ve never seen, and probably won’t, because you weren’t born into it. Let me explain it this way. Most people are hooked, line and sinker, on the physical.

You see, being an African in this country, you’ve got to do it yourself. If you’re waiting for God, you’re going to be waiting a long time. You can worship and carry on, but anything you do, you’re going to have to do it yourself.

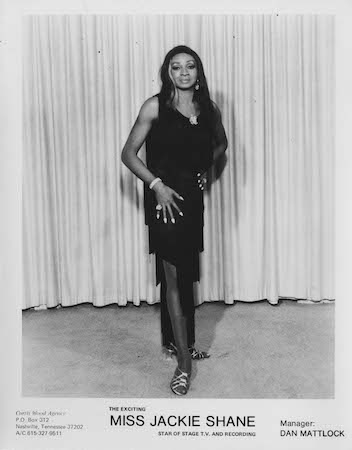

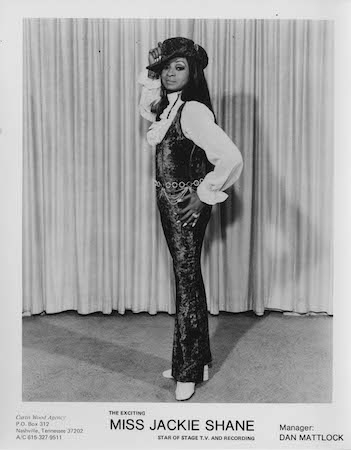

JS: Mmm, Miss Stuff. Give it to them, girl (above).

DM: What was the Curtis Wood Agency?

JS: I don’t know. Just another agency. I didn’t sign with just one.

DM: So I’m noticing that these are Nashville, and you’re all dolled up, and it says, “Miss Jackie Shane.”

JS: I needed some new lobby pictures, so I had those done here. Then I left and went back to LA. [Sighs.] I don’t know what to say about them. They’re just two pictures of me, as cute as I am. Oh, she’s so hot. Gone girl. And she’s smiling.

DM: Are you saying, “Go on, girl,” or, “Gone girl”?

JS: When you get soulful, look out. You don’t say, “Go girl,” you say, “Gone girl.”

When you get soulful, look out. You don’t say, ‘Go girl,’ you say, ‘Gone girl.’

DM: Where are you here? (above)

JS: [Sighs.] I don’t know. I’m in my early twenties. This was Toronto. I like to think. I don’t really like posing. I like to think of something when I’m going to be snapped. If you look at the eyes, you’d say I’m looking into the future. What I’m thinking, I have no idea.

DM: Tell me about the rings.

JS: The ruby ring and the other one is probably a diamond ring. I just had bought them, maybe a week or so before this was taken. I think this is the same studio where John Wayne and I met.

DM: You’re in the red suit. (below)

JS: Isn’t she cute? Hot stuff. Keep ’em guessin’, Jackie.

DM: So that’s [Jackie’s bandleader] Frank Motley in back.

JS: And Curley Bridges on the piano, and King Herbert on the saxophone.

DM: Where is this?

JS: Downtown Toronto. On Yonge Street.

DM: With you and Frank, who was the boss?

JS: No boss—Frank was the bandleader, and I would tell him what I thought. Frank wasn’t really into show business. He wanted to be Louis Armstrong, but there already was one. On the weekend, he would drink. And when he drank, he was a monster; he’d go from Jekyll to Hyde. Everyone was trying to get Frank to settle down. He was just a tornado. But when I told him to go sit down, he sat.

[Jackie proceeds to tell a series of stories of Frank’s bad behavior, including several incidents of “chasing” Jackie, and Jackie putting Frank in his place.]

DM: So why Frank, why did you work with him? Was he especially talented?

JS: No, it was more of a job. I didn’t know how long I’d be with him, but it was a long time. [They worked together off and on from 1959 to 1971.]

DM: Let’s talk about the South for a moment, since there’s a theme to this issue [Music & Protest], and there’s a political story in your career—going to Canada where you were better accepted as an artist.

JS: I wasn’t better accepted as an artist, I was accepted.

DM: Were you accepted in Nashville?

JS: Of course! But it’s the evil creatures that crawl around in the South. They’re ridiculous, they’re stupid. I remember, this group came from this recording company, and they wanted to record me. And we were set up at the recording studio, and they had the audacity to want me to sing on this European boy’s record, and give him the credit, and I got up and left.

They wanted me to play the Opry, and I said no. If they gave me 25 percent of Nashville, I wouldn’t do it. I had a ball around here, but as [southern soul legend and James Brown rival] Joe Tex said to me, “Get out of here, you have too much to offer.”

Look at what they did to DeFord Bailey—he was a pioneer of the Grand Ole Opry. His son played bass for me. After he passed, he worked forever to get him into the [country] hall of fame. He had to shame them into doing it. And [the popular 1960s Nashville soul music television program] Night Train, they destroyed it because it got too powerful.

DM: Who’s “they”?

JS: The European hillbillies! They know that soul music is the most powerful music on earth, you can take it any place—where they don’t speak the language— but they can feel it.

DM: So I have to ask, what do you think of country music?

JS: I think country music is fine. [Long pause.] It is some of the most powerful lyrics, but it’s not the same thing. Country music is, you know . . . country music. “You Are My Sunshine”—I did it as soul. I did it the way I feel it.

DM: Do you think you have any responsibilities as a popular entertainer to take political stands?

JS: No, I don’t think I do. I can, because I live in this world, but I don’t have a responsibility. If there’s something I see that is wrong, and I have that platform, I will say something. Like drugs—when the Beatles and the Rolling Stones started that nonsense, that you won’t be able to understand what we’re doing with LSD, I went up against that.

DM: What do you think about tearing down Confederate statues?

JS: I think it’s good. They lost. You have no idea the evil that’s in that. You didn’t go through the evil that African people went through. You have no idea what it’s like to be treated that way.

DM: Why did you come back to Nashville?

JS: My people, my family, needed us [by “us,” Jackie means her mother Jessie], and I was raised to help them—whether they wanted our help or not. And I thought to myself, if they were bombing, they weren’t going to bomb Nashville.

DM: Why have you stayed so long?

JS: I don’t know. I guess [laughs] . . . They’re not going to blow up Nashville, Tennessee. But it’s also a place where you can take it easy. You can take it so very slow. And what’s happening in other places doesn’t interest me.

A longer version of this interview appears in the Music & Protest issue (vol. 24, no. 3).

Douglas Mcgowan’s reissue projects include the new age anthologies I Am The Center and The Microcosm; collections of music by Joanna Brouk, Jackie Shane, and the Eugene Electronic Music Collective; and the best-selling ambient sound app for iOS, Environments. He lives in Los Angeles.

Header image courtesy tommybuddy, September 16, 2015, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.