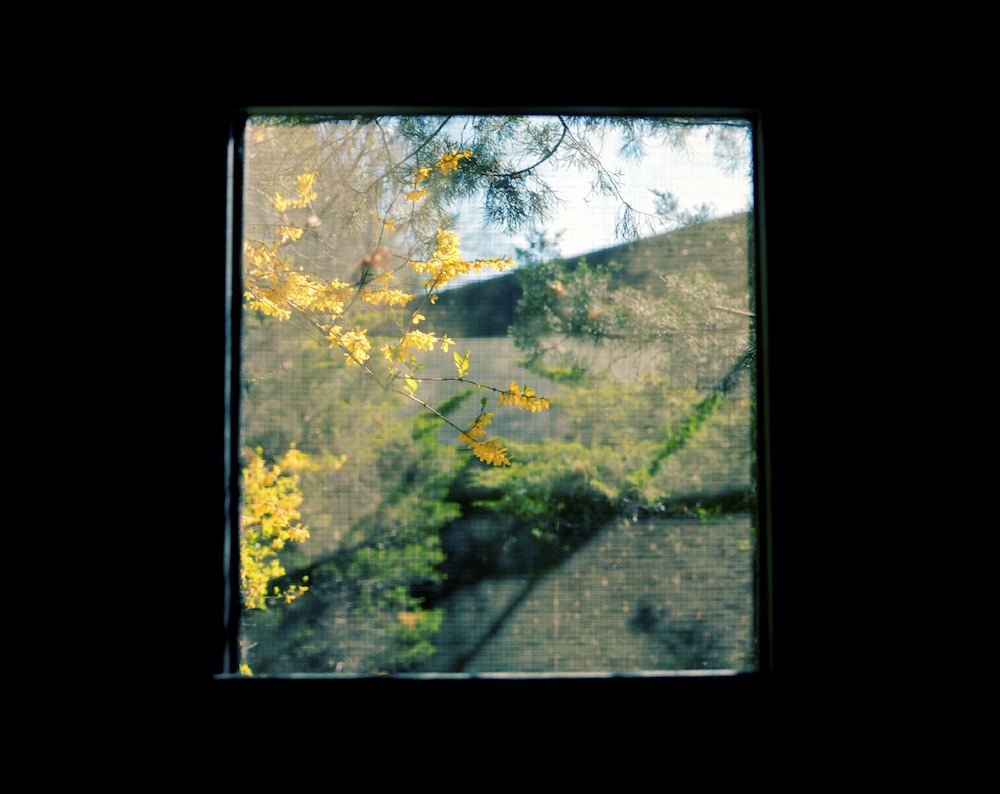

“The mountains of western North Carolina are beautiful beyond description, and it is as if the atmosphere of the College was consciously a part of the living beauty. It made one sensitive to everything.” —Doughten Cramer, Black Mountain College Student

It’s been more than eighty years since Doughten Cramer was a student at Black Mountain College. The school is long closed, the landscape has certainly changed. And yet, every time I set foot on Black Mountain College’s former Lake Eden campus, I share that same feeling. I become sensitive to everything. But despite the visceral effect of this specific place on a wide range of students, faculty, and even the subsequent admirers of the school that tour Lake Eden today, the importance of environmental stewardship and reverence at the College are often footnotes in its history.

This is at least in part due to the awe that even a partial list of students and faculty inspires. Between 1933 and 1957, Josef Albers, Anni Albers, Ruth Asawa, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan, Buckminster Fuller, Charles Olson, Elaine de Kooning, Willem de Kooning, Gwendolyn Lawrence, Jacob Lawrence, Kenneth Noland, Barbara Morgan, Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly, Susan Weil, Jonathan Williams, and Marion Post Wolcott attended or taught at Black Mountain College. Many of these artists are now part of the canon of American art and literature, and it is often the knowledge that many of them lived and worked together in the same place that sparks curiosity about the school.

This is how I first came to know about Black Mountain College. As a young artist from Virginia, the discovery of an experimental art school in North Carolina was meaningful. It proved that there was a path for artistic discovery that lay outside of the cultural centers of New York or Los Angeles, places which seemed all but inaccessible to me at the time. But in museums and art historical texts, it is the names of artists and their finished works that are foregrounded in descriptions of Black Mountain College. Their vast achievements are worthy of acclaim, to be sure, but such a discourse privileges the outcomes of the school and overlooks the time spent there, which is what the College actually valued most. Above all else, Black Mountain College prized process and experimentation. To quote Josef Albers, the first art teacher at the College, “We do not always create works of art, but rather experiments. It’s not our intention to fill museums, we are gathering experience.” And the experiences gathered at the College were a direct result of the convergence of place and pedagogy.2

In terms of place, the College was always situated in Black Mountain, North Carolina, a small town 16 miles east of the county seat of Asheville. This location, in the idyllic foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, provided space, seclusion, and beauty. In 1934, just a year after the founding of the College, photographs of the landscape dominated promotional materials. A pamphlet from 1934–35 titled “Views of and from the College” depicts the first temporary campus at the Blue Ridge Assembly YMCA. The brief text describes its proximity to the train line that ran from New York to Asheville. But the main feature is a fold-out panorama of the Great Craggy Mountains. With no description of the curriculum or faculty, it is clearly the environment that the College prized and would continue to promote throughout the life of the school.

By 1937, the faculty had purchased 725 acres of land and fourteen buildings at nearby Lake Eden. Moving to Lake Eden was transformative. The collective purchase of land was symbolic, but just as importantly, the shift to Lake Eden provided some stability and a permanent home for the College. Faculty and students could, for the first time, live and work in one location year-round. This commitment to one place also facilitated the development of the building and work programs that would come to define the school. Soon after the move farming, groundskeeping, building renovation, and design-build programs to preserve and sustain the campus, became part of daily life. These communal efforts to steward and subsist on the land instilled a certain pride of place, but also a reverence for it, that was echoed within the art curriculum.

When Black Mountain College was founded in 1933, another radical school across the Atlantic, the Bauhaus, was forced to close under pressure from the Nazi government.3 Many of its members emigrated to America, including Josef Albers, who established the art program at Black Mountain. Albers famously focused on teaching students how to see, rather than how to employ specific painting or drawing techniques. In the College’s second Bulletin, Albers discusses his methodology:

“In short, our art instruction attempts first to teach the student to see in the widest sense: to open his eyes to the phenomena about him and, most important of all, to open his eyes to his own living, being, and doing.”4

Much of the living, being, and doing at the College, including classes of all disciplines, took place outside. Class instruction emphasized observation, description, and the collection of found materials on campus grounds. Students were encouraged to become sensitized to their everyday environment through close observation of forms, sounds, and movements in the landscape. The pedagogical ethos held that making cannot be separated from where the making is done; the ability to see cannot be separated from what is possible to be seen. With this context in mind, it’s perhaps easier to understand why Doughten Cramer proclaimed that he felt “sensitive to everything” amid a College atmosphere that was “consciously a part of the living beauty” of its environment.

Albers’s philosophy of seeing, taken in combination with the landscape of Black Mountain and the College’s imperative to contribute to and sustain the environment, created the possibility for a way of life that was quite different than what was on offer in most of midcentury America. The boundaries between life and art, labor and care, nature and culture, self and community started to break down. Being and environment had the potential to merge, as writer Tyler Laminack has observed: “What we see is that within the space of the school, nature is inseparable from culture; it affects organization at the psychic level.” Laminack goes further to characterize this interconnectedness at Black Mountain College as an instance of “natureculture.” A term originally introduced by scholar Donna Haraway, Laminack applies it here to illustrate the school’s “deconstruction of the binaries of nature | culture and self | environment.”5

In an academic context, natureculture requires much framework, but viscerally, I understand the concept immediately. Natureculture was the ethos of Black Mountain College. And in a literal sense, this is what I focus on when I photograph Lake Eden; the culture of nature that inspired a way of life. In the eight years I lived in North Carolina and visited Lake Eden, my motivation was never to repeat what the original students made, and I never expected to see exactly what they saw. However, I did want to feel something of what they felt, to be a part of natureculture. When I go to Lake Eden with my camera, I can, and I do. I become sensitive to everything.

That said, my trips to Lake Eden were never purely mindfulness exercises. I suppose that I’ve harbored a bit of hope; that if I could help perpetuate this story of a natureculture in the Blue Ridge Mountains, if I could show that it was possible, perhaps it could be possible again. When I think of this prospect, I recall the first line of Robert Duncan’s poem, “Often I am Permitted to Return to a Meadow”:

As if it were a scene made-up by the mind,

that is not mine, but it is a made place . . .6

Black Mountain College and the Lake Eden campus were made places. New places, new naturecultures, can still be made for the purpose of living, being and doing with open eyes.

This photo essay was published as a longer online feature in conjunction with the Human/Nature Issue (vol. 27, no. 1: Spring 2021). For more, see McCarty’s Snapshot, “View From Quite House.”

Lisa McCarty is a photographer and writer based in Dallas, Texas, where she is assistant professor of photography at Southern Methodist University. McCarty has participated in over eighty exhibitions and screenings, nationally and internationally. Her books include Transcendental Concord (Radius Books) and A Time of Youth (Duke University Press).NOTES

- Doughten Cramer, “A Hike to Craggy Dome,” Black Mountain College: Sprouted Seeds: An Anthology of Personal Accounts, ed. Mervin Lane (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1990), 46.

- Leah Dickerman, “Bauhaus Fundamentals,” Bauhaus 1919–1933: Workshops for Modernity (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2009), 17.

- “The Bauhaus after 1933,” Bauhaus-Archiv, https://www.bauhaus.de/en/das_bauhaus/81_nach_1933/, accessed October 20, 2020.

- Josef Albers, “Concerning Art Instruction,” Black Mountain College Bulletin, no. 2 (1934), 4.

- Tyler Laminack, A New Art of Living: The Three Ecologies of Black Mountain College (Georgetown University, MA thesis, 2006).

- Robert Duncan, “Often I am Permitted to Return to a Meadow,” The Opening of a Field (New York: New Directions, 1973), 7.