While riding my motorcycle on Louisiana Highway 77 in 2014, I encountered a group of nearly fifty people on horseback. They commanded the narrow, two-lane road that runs along Bayou Grosse Tete, and I pulled off to the side for them to pass. As they rode by, I retrieved my camera from the saddlebag of my bike and took a few photographs. People waved, hollered, lifted drinks, and tilted hats, giving themselves to the camera. A gentleman I’d later meet, Henry, motioned to me from the end of the procession, encouraging me to join them. I was immediately aware of the rare opportunity I had been granted, turned my motorcycle around, and began to follow, occasionally pulling ahead to photograph the loose procession of riders.

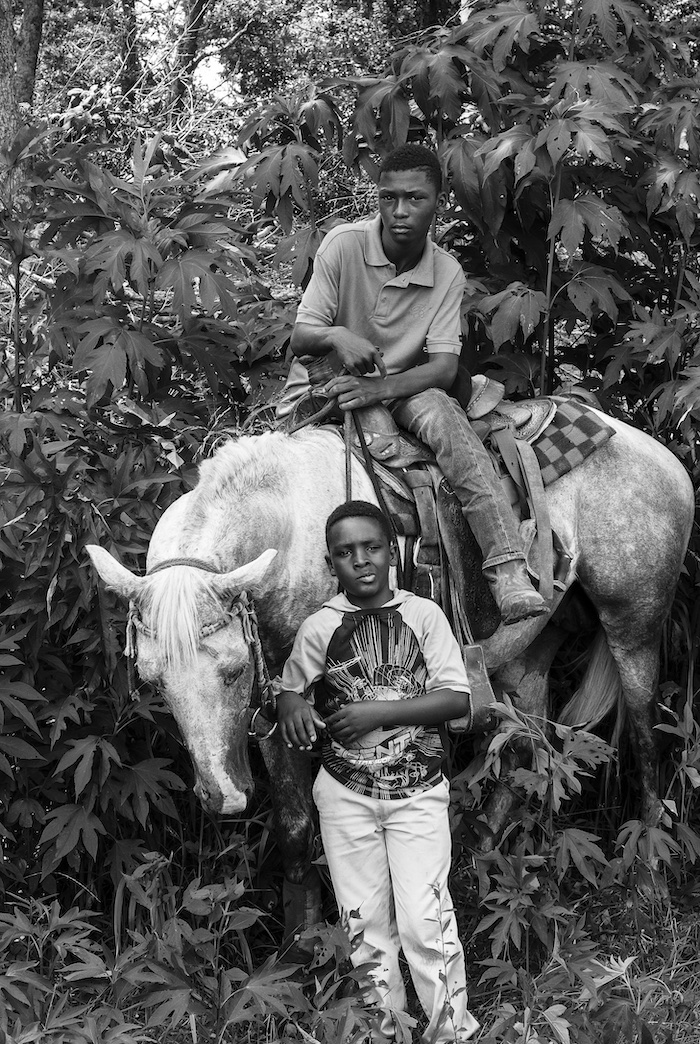

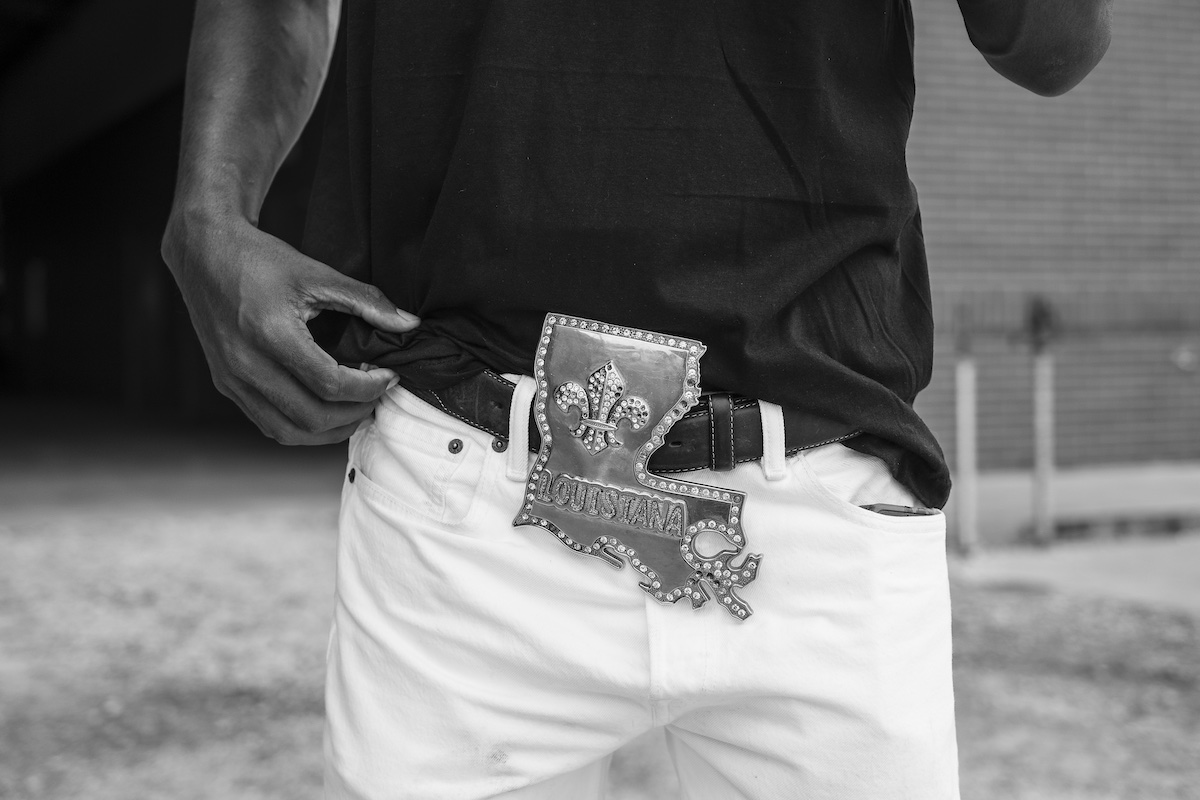

The ride concluded several miles down the road in a large open field. I took off my helmet and jacket and mingled with the riders. Zydeco music was playing, jambalaya was cooking, riders demonstrated their equestrian skills, and a small crowd placed bets on two men about to race their horses. I was drawn in by the generations of people spending the day together, the mix of rural and urban sensibilities—white tank tops, gold chains, tattoos, cowboy hats, studded belts, and western boots. So much about the scene felt familiar and also surprising. Though I had been to many festivals and parades in my eight years in Louisiana, this was a distinctly different affair.

It was an overcast day in March and the sun was beginning to set. Over the next hour or so, I made a few photographs but mostly struck up conversations, inquiring about the scene I had stumbled into. I asked someone I’d met if they rode often and learned that the trail riding clubs gathered every weekend. Once the sun went down and I prepared to pull away, a woman standing near the exit to the field gave me a Xerox copy of a handwritten flier for the next ride with a phone number scrawled on the back to call for directions. So began nearly five years of riding and making photographs with Louisiana’s trail riding clubs.

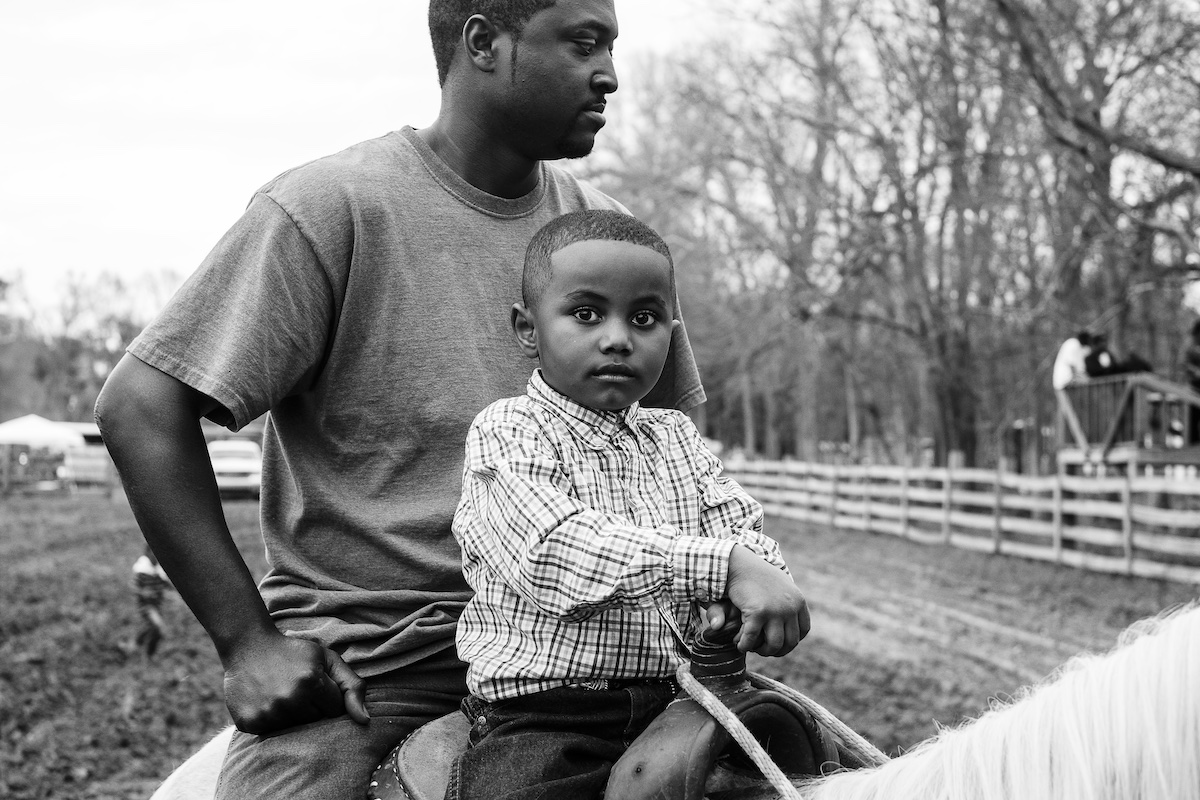

I was raised in Kansas and had a particular image of a cowboy that was shaped by popular culture. He was gruff, serious, situated in the West—and white. The trail riders in Louisiana are a stark contrast to most familiar depictions of cowboys, but I would later learn that this specific Black equestrian tradition stems from a time when the Louisiana Territory was in fact the American West. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in the prairie grasslands divided by water in Southwest Louisiana, horsemanship became a way of life for the people of color who worked the land—both enslaved and free, whose descendants make up the Creole population that remains vibrant to this day.

The present-day trail rides are an outgrowth of those early practices, which predate the hired hands whose role driving cattle in the mid-to-late 1800s gave rise to the archetypal figure of the American cowboy. These men on horseback would come to occupy an outsized place in the collective imagination of our country, both then and now. They fueled dime-store novels, television, cinema, and many a country song. In these stories, the cowboys were always white. This wasn’t representative of the reality of life on the range, where an estimated 25 percent or more of these men were people of color: Black, Latinx, and Native American riders. Prominent Black riders include members of the Civil War regiment of the Tenth Cavalry, known as the Buffalo Soldiers, the first all-Black unit in the US military. Twenty-three of its members received the Congressional Medal of Honor; it was the highest decorated cavalry in US history. Another example of a Black rider relegated to the sidelines is the African American lawman Bass Reeves, thought to be the inspiration for the fictional crusader the Lone Ranger. Reeves was born into slavery in 1838 and escaped to the Indian Territory of present-day Oklahoma. Following the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery, he worked as a deputy marshal bringing criminals to justice. His cunning, wild escapades, and masked face fueled countless stories. Many of the fugitives he caught were incarcerated in Detroit where, in 1933, the radio program The Lone Ranger would debut. In 1949, The Lone Ranger rode onto television screens, but in this fictionalized version of Bass’s story, the mask was worn by a white man. The 2019 HBO series Watchmen pays tribute to Reeves when, in the opening scene of the first episode, a young boy in a Tulsa movie theater watches a silent film featuring the adventures of the Black lawman Bass Reeves while the race massacre of 1921 unfolds outside. If popular culture can conceal reality, it can also reveal it; this contemporary onscreen depiction was the first time many Americans became aware of this historic event. The Tulsa Massacre resulted in the deaths of as many as three hundred people and the displacement of thousands when the community and economic center known as Black Wall Street was ravaged and destroyed by white supremacists.

Though I had been unfamiliar with Louisiana’s trail riders when I first encountered them, the central mission of my artwork has long been to interrogate America’s mythology of the West. With long-term photographic projects that scrutinize the beliefs underlying Manifest Destiny, I seek to understand how and why this landscape—real and imagined—remains an essential part of the American mythos. From the movie star cowboy president Ronald Reagan to brush-clearing George W. Bush and, later, the unlikely Donald Trump, the nation’s presidents have used the rhetoric of Manifest Destiny to cloak their political strategies, summoning images of the Old West to promote public policy. Bush regularly strode around his Texas ranch and reduced complex geopolitical issues to the language of Westerns, perhaps best exemplified in his “axis of evil” speech where he announced to the world, “You’re either with us or against us.” If the imagery of the West has often been subtext, it became text in the speech Trump read at the 2020 Republican National Convention:

We cannot help but marvel at the miracle that is our great American story. . . . When opportunity beckoned, they picked up their Bibles, packed up their belongings, climbed into their covered wagons, and set out West for the next adventure. Ranchers and miners, cowboys and sheriffs, farmers and settlers. They pressed on past the Mississippi to stake a claim in the wild frontier. Legends were born. Wyatt Earp, Annie Oakley, Davy Crockett, and Buffalo Bill.

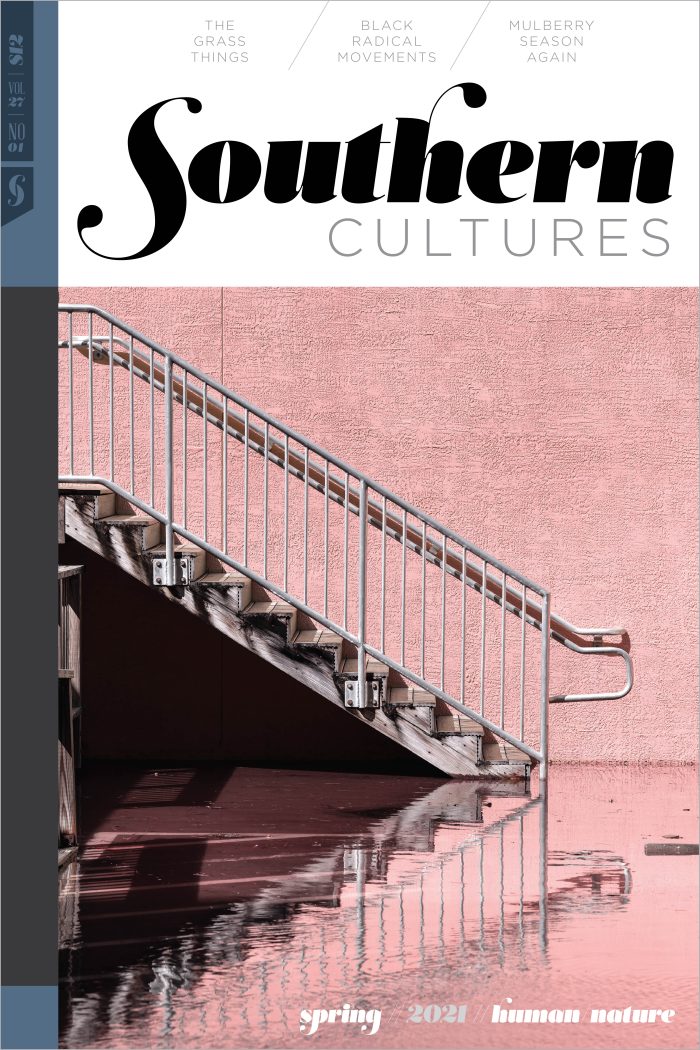

These stories have run their course. Of greater relevance today are the Crescent City Cowboys, the Country Riderz, the Buffalo Soldiers, and the Stepping-In-Style Riding Club, just a few of Louisiana’s trail riding clubs. The affiliate names often combine a pride of place with a nod to popular Western iconography and contemporary Black culture: the Kountry Bunnies, Good Ol’ Boyz, Ride or Die Riders, Bayou Boyz. The names read like poetry and suggest the trail riders’ pride in a powerful history, and it is this dignity and delight that I’ve tried to capture in my photographs. I hope these images can serve new narratives that celebrate the complexity of the America we live in today and the richness of the histories that brought us here.

I embarked on this project at the time of the fiftieth anniversary of many of the achievements of the civil rights era and in the wake of the Trayvon Martin killing. Violence and indifference to the value of young Black lives came to the national spotlight in incidents across the country, from Ferguson, Missouri, where Michael Brown was killed, to my home in Baton Rouge, following the murder of Alton Sterling in 2016. In the two years since Louisiana Trail Riders was published, the list of Black men, women, and children killed by police has only grown longer. After George Floyd’s murder in 2020, people spilled onto the streets in protests across this country and in cities around the world. Amid the media coverage of Black Lives Matter, a few figures on horseback caught peoples’ attention and sparked viewers’ imaginations, including images of Brianna Noble in Oakland (May 29, 2020), Black riders demonstrating in Houston (June 3, 2020), and the Compton Cowboys Peace Ride in Los Angeles (June 7, 2020). They were not only participating in an American tradition of protest; these Black men and women were in the streets on horseback, where the saddle has often been reserved for military and law enforcement officers. They have taken the reins of a symbol long associated with independence and power. Though they have always been riding, Black riders are finally getting the attention and respect they have long deserved.

I hope these photographs bring attention to this corner of Louisiana’s cultural heritage while presenting a counternarrative to the limited depictions of Black life in popular culture. Together, the images serve as a testament to the complexity and joy that is present in Southwest Louisiana—where vibrant communities share this generations-old tradition and make it new.

This photo essay first appeared in the Human/Nature Issue (vol. 27, no. 1: Spring 2021).

Jeremiah Ariaz is the recipient of numerous awards and his photographs have been exhibited internationally. Louisiana Trail Riders (University of Louisiana Press, 2018) bridges Ariaz’s long-standing interest in the American West and his current home in the South, where he is a professor at Louisiana State University. For more, visit www.LouisianaTrailRiders.com.