When I was ten, for my father’s fifty-seventh birthday, I made him an acrostic poem card. After the “B” for “Brave” and the “R” for “Really Wonderful” in his first name BORIS was the “E” for “Expert on Aldo Leopold” in our last name ZEIDE. Aldo Leopold, as in the renowned author of A Sand County Almanac (1949), considered to be the father of environmental ethics and wilderness conservation in the United States.

From the time that I could read, in the evenings after dinner I would follow my dad to his desk in his home office nook. There, he would open his laptop—technological magic to me then, in the early 1990s—and its WordPerfect documents. He was always working on an article, with towering piles of books on his desk and nightstand. I knew he was a forestry professor but understood little about what that meant, or how it connected to the words on the screen: “Fractal dimensions of tree crowns in 3 loblolly-pine plantations of coastal South-Carolina”; “Has Pine Growth Declined in the Southeastern United States?”; “Analysis of the 3/2 Power Law of Self-Thinning.” Now I know he worked on forest mensuration—the science of measuring trees—and that he was an expert in the mathematical modeling of tree growth. That in 2016 the fifth edition Forest Mensuration textbook would include my Papa’s name: “We also acknowledge the passing of several other great mensurationists since the publication of the last edition, many of whom are cited throughout this text … They dedicated their lives to forest mensuration, advanced our knowledge of its principles and applications, and contributed much to the education of the current generation of mensurationists.”2

But as a kid, I was there less to understand his scholarship than to help correct his English grammar. He was a Russian Jewish immigrant who left Moscow in 1973, passing through Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Harvard Forest in central Massachusetts, and Rutgers University, before making his way in 1980 to the University of Arkansas School of Forestry, located in a rural southeast Arkansas town of eight thousand people (and of many, many more trees). I was a precocious kid who loved spelling bees, diagramming sentences, and helping make my Papa’s language flow.

Of all the topics my dad worked on, the one that stuck with me as a kid—as my acrostic poem attests—was Aldo Leopold. He was a real person, a character who emerged in my dad’s recounting fully formed and dynamic, bringing with him a human interest that the loblolly pines and laws of self-thinning did not.

I didn’t really understand as a child what it was that Papa wrote about Leopold, or why his 1998 Journal of Forestry article “Another Look at Leopold’s Land Ethic” would be received with so much contention. I just knew that the stories he told about this man, who had lived years earlier, far away in the cold northern state of Wisconsin, reminded me of the stories Papa told about himself. Both men were forestry professors who found solace walking in the woods and reading poetry and prose that engaged with nature. Both retreated to rural places to build their true homes, preferred being outdoors to in, and devoted their lives to the woods that give us all life.2

I remember that, when that Leopold article came out, my mom would often tell my dad in the evenings that he should try to be less provocative, that he should get along with his department head and not stir the pot so much. Would it hurt to just fit in a little more? she wondered aloud.

This tension around fitting in was often central in my parents’ arguments. My dad had lived his life in such a way that he stuck out in nearly all settings, except in the forest. He stuck out as a child in urban, rumbling Moscow in the 1940s, where he never felt at ease until the first time he left the city by train and glimpsed the miles of green forests beyond the city. The trees called to him. He stuck out when he pursued forestry as a profession, not the expected route for a smart young Jew in the Soviet Union of the 1950s. He stuck out most of all when he rejected the elite institutions of the Northeastern United States and petitioned for a job at the most rural forestry school in the country, finding himself a Russian Jew with a thick accent in a hidden corner of Arkansas in the tense Cold War days of the 1980s.

That is where I grew up, in a place that clearly marked me, too, as an outsider. I struggled to fit in with the kids around me, to find others who laughed at my jokes, who shared my love of reading and spelling, who understood my Jewishness, who would help me find community outside of church, deer hunting, and football.

The difference between me and Papa was that he thrived in his role as the eccentric character, did not seek to fit in, found such joy in the loblolly pines and sweet gums and oak trees that people or culture mattered little. For him, Arkansas was paradise. He and my mom built a house outside of town, deep in the forest. He had two big gardens where he grew tomatoes and okra, cucumbers and dill, parsley and blueberries, muscadine grape vines winding all around. He carved a path through the woods directly to the university, and every day he walked that path to work and back, often meandering to let his thoughts percolate, taking up to an hour to walk the two-mile route, doing his best thinking in that space. He would lie on his back atop fallen logs, remove his sturdy boots and portyanki (Russian foot wraps he wore in place of socks), and wiggle his toes in the air. When I walked with him, he made me do the same, and exclaimed, “This is the life!”

When I begged to differ, to imagine a different kind of life, he would say, “Anechka, look at the sky! Look at the trees!” He encouraged me to consider my classmates as William Faulkner would have, to see literary possibilities in the clash of cultures. Observe them as an anthropologist would. That perspective, however, brought little solace.

When I begged to differ, to imagine a different kind of life, he would say, “Anechka, look at the sky! Look at the trees!”

I left Arkansas as soon as I could, headed off to a state-funded math and science residential high school at fifteen and then to college in St. Louis at seventeen. I studied biology because it seemed like what I should study, because pursuing the pre-med track was what smart kids like me did. Science was the path laid out for me. But my eyes began to wander toward the sociology, anthropology, and environmental studies descriptions in my university’s course catalog. I took on a second major in environmental studies. One fateful semester, I took a history of life sciences course for my biology major and a separate environmental history class. I had never really studied history, had skipped my high school’s intensive world studies and American studies courses by fulfilling my requirements in less demanding (and less engaging) versions at my local small-town college. But here I was thinking about the natural world, not just as it is but how it came to be. And I loved it. Asking my professors about their backgrounds led me to the University of Wisconsin–Madison for its PhD program in the history of science, one of the oldest and best-known of such programs in the nation.

In our regular phone calls, my parents expressed some confusion regarding my path: But I thought you loved biology? What is history of science anyway? How do you get a job in such a field? Isn’t it too cold in Wisconsin? Are you sure you want to do this?

In our regular phone calls, my parents expressed some confusion regarding my path: But I thought you loved biology? What is history of science anyway?

I wasn’t sure. I didn’t know what it meant to get a PhD or what doing historical research even looked like. Still, an internal compass led me in this direction, some pull that told me studying the history of science and the environment would help me find the thread that, if pulled, would unravel all the puzzles I saw around me. I wanted to understand why my creative friends at college wanted to major in the humanities or arts, and thought science was boring. I was fascinated by the scientific rhetoric used in reporting on pressing environmental issues. I sensed that the key to understanding confusions around issues I cared about—like nutrition and climate change and breastfeeding—lay in thinking about the how science is funded, practiced, and communicated.

Coming to Wisconsin also brought me back to Aldo Leopold. In my second year of graduate school, one class field trip took me through southwestern Wisconsin, where I saw the quartzite bluffs at Devil’s Lake State Park, the spectacular gorge and moss-covered walls at Parfrey’s Glen, the historical crossroads of the city of Portage, and, significantly, Leopold’s historic farm and famous shack in Sauk County. This landscape had inspired Leopold’s defining work, his “land ethic,” published in 1949, which powerfully argues that “a thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.” This formidable and unambiguous statement influenced generations of environmentalists, ecologists, and environmental historians. Foresters, too, as it would turn out.3

I toured these places then, took photos of the conifers and hardwoods standing tall on Leopold’s land, the outcome of the restoration he had practiced some seventy years earlier.

I wove his land ethic and his other professional work into my master’s thesis on the history of conservation education in 1930s Wisconsin, and Leopold’s role in it. I spent many days leafing through the Leopold Papers in the dusty basement archives of Steenbock Library, admiring the loops and whorls of the man’s handwriting as I sought to understand what drove and challenged him, what occupied his days.

Through all of this, I talked with my father frequently, sometimes giving him updates on my research, but often leaving out the details, as I still felt his bafflement over the path his daughter had taken. I don’t remember any flash of recognition from him, any sense that he connected my work with his own.

A year after I walked on Aldo Leopold’s land, my parents sold and moved away from theirs. The Arkansas acres that had nurtured me, that had been an extension of my father’s self, that held the sky and the trees that defined Papa’s life and work, were no longer ours. My father was retiring from his professorship, my brother and his wife in Atlanta were about to present my parents with their first grandchild, and my mom’s sacrifice of living in the backwoods for so many years had caught up with her. And so, my parents moved to a northern suburb of Atlanta.

Papa may have retired from his official position, but he continued to produce scholarship and to walk in the woods every day, this time in the forests surrounding Kennesaw Mountain, which was adjacent to my parents’ new backyard in Georgia. His attention had turned away from forest mensuration and toward a unifying theory of the science underlying forestry. His wide-ranging reading moved into history and philosophy of science. In 2008, the Journal of Sustainable Forestry devoted its entire fourth issue, all 128 pages, to Papa’s book-length article titled simply and audaciously “The Science of Forestry.” In it, he sought to “make forestry a science by consistent reasoning from first principles,” based on what he called his “1-2-1 method,” which “defin[es] one problem, designs two opposing explanations, and then fuses them into a single solution.” In working on this, he radiated intellectual stimulation. It was his life’s work, and it animated him. In our conversations throughout my time in graduate school, he tried urgently to convey to me why his method would apply not only to forestry but to anything I was working on. After he died, I found among his papers a handwritten sketch of his attempts to organize my dissertation topic—a history of the canning industry—in accordance with his method. His brain was always whirring, trying to make connections across vast fields of inquiry.4

In 2011, my mom awoke in the middle of the night to my father having a seizure in bed next to her. A call to 911, an ambulance ride to the er, initial scans the next morning, and a biopsy several weeks later led to a diagnosis of a Grade IV glioblastoma multiforme, the most aggressive form of brain cancer. Grief engulfed us. I flew to Georgia, hugged Papa too tightly, buried myself in researching treatments, and arranged his pills in the tidy compartments of the plastic pill organizer. I pulled out my voice recorder, pressing “record” throughout the conversations of those desolate and intimate months. Papa and I had already spent hundreds of hours recording our conversations in the preceding years. I had captured his oral history narratives through Skype calls as he read and translated for me the journals his mother, my grandmother, who was born in 1907 and lived in Russia her whole life, had written some years earlier as she neared death.

In the days right after his diagnosis, I recorded one conversation as my father and I lay side by side on his bed. In the recording, you can hear him begin the conversation by saying to me, in Russian, “Anechka, the reason that you are here in Georgia visiting, in some large part, is so that I can convey my research findings about nature to you . . . eh?”

There’s a pause, and then my voice, careful, “That’s not the most important.”

“Of course not the most important,” he replies, “but . . . quite significant. Everything else is just details.”

I remember squeezing his hand as I said, “Holding your hand?”

You can hear him growing a bit impatient. “Yes, yes, that’s important. But what I’m talking about is something different. That I was a forestry professor, thought about how trees grow, then began thinking about more general things, and came to the conclusion that there’s a central question, one I’m still chewing on. All philosophy is built on one idea, that [switching to English] ‘any proposal can be answered in terms of true or false.’ [Back to Russian] This is an amazing thing! So, what I’m trying to figure out is that there’s another kind of proposal, one that can’t be answered in terms of true or false. That there are proposals that are simultaneously true and false, but in specific respects. This is similar to the idea of complementarity, proposed by Bohr, the physicist, you’ve heard of him?”

And so it went from there. His brain abuzz, hard at work, even as the tumor grew.

A few weeks later, Papa was gone. Unwilling to submit to the progressive cognitive deficits, seizures, incontinence, difficulty swallowing, blindness, and other effects that were soon to come, Papa took his own life.

There had been anticipatory grief in the months immediately after the diagnosis, but his death brought new, turbulent, overwhelming waves. I managed some of it by digging deep into the stories that had undergirded our relationship for the twenty-seven years I’d had him as the solid core at the center of my life. I wrote about him, I talked about him, I studied photos of him, I processed my memories and all the stories about his eccentricity and remarkable brilliance with anyone who would listen.

And I also dug back into his scholarly writing. Somewhere in the middle of the three-and-ahalf months between his diagnosis and death, he had sent me an email, attaching all the files of the work he was in the middle of but recognized that he would not be able to finish, building on his 1-2-1 method. He had written, “This work is in several sections. … It will be enough to read to the end of your career. Samoe glavnoe: ia lublu tebia, ochen preochen! [Most importantly: I love you, very much!]”

This process led me also to rediscover what he had written about Aldo Leopold back in 1998—and, more strikingly, to rediscover the controversy that his provocative essay had created. I reread Papa’s “Another Look at Leopold’s Land Ethic” and in it I saw the sharp humor, wry observations, contrarian viewpoints, and desire to push against the status quo that characterized my father. I disagreed with many parts of it, sure, but certain categories of intellectual disagreement had always been part of our relationship. On the one hand, Papa lived his life more in accordance with “environmental values” at the individual level than anyone else I knew—he rarely drove a car, he was a vegetarian and didn’t eat any processed food (no sugar, salt, or oil), he grew much of his own food, he felt deeply connected to the outdoors, he didn’t like air-conditioning, he almost never shopped or bought new things, and so on. On the other, he did not like “environmentalism” nor the political actions that underlaid the environmental movement. His years under the dictatorial communist regime of the former Soviet Union had made him allergic to politics and federal government action. Yet he also thought recycling, switching out light bulbs, and other late-twentieth-century preoccupations with microscale changes were meaningless.

I didn’t understand any of that, finding it difficult to reconcile how similar we were in our habits and yet how much our ideas often diverged. But still, I admired him, respected his positions, found his views challenging and worth engaging. Apparently, not everyone did. When I read the responses to his 1998 Aldo Leopold essay, I was stunned. It was the first time I’d seen Papa’s complicated ideas torn apart in a public forum, debated by someone besides me, by people who did not know the context or understand his voice. I wanted to stand up for him, to shout, “You don’t get it!” at his critics. And yet, I agreed with them, on paper, more than I did with him. They were the ones who were on my “team”—the environmental ethicists, representatives of the Wilderness Society, and protectors of the natural world.

“I wanted to stand up for him, to shout, ‘You don’t get it!’ at his critics. And yet, I agreed with them, on paper, more than I did with him.”

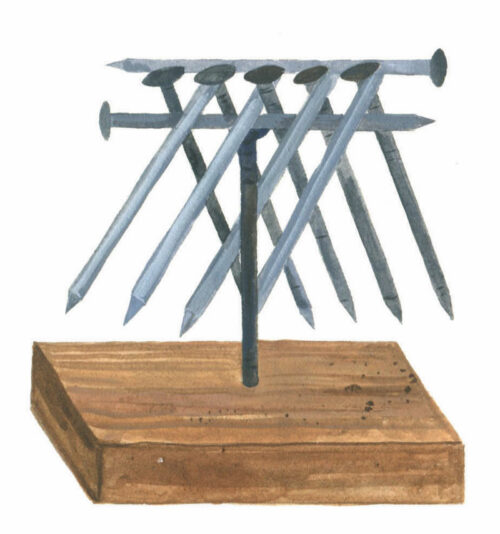

At the center of the debate was Papa questioning the ecocentrism inherent in Leopold’s land ethic, and its adoption as a mantra by the forestry profession. He challenged the idea of the ecosystem as a truly interconnected system, or superorganism, in which the removal of one piece leads to the collapse of the whole. This is not how nature works in practice, he argued. (I remember how, as a kid, Papa discovered the balancing nail puzzle at a family friend’s house, in which the challenge is to balance eleven nails on the head of a twelfth nail that is hammered into a block of wood. The elegant solution has you create a sandwich of two nails, with the remaining nine nails in between, staggered across from each other, the nail heads holding them in place between the two outer nails. Then the whole assembly balances upon the stationary nail. “This,” I remember Papa exclaiming, “is a true system!” So, he made his own version at home, labeling it “true system,” and a second version labeled “ecosystem” that simply had twelve nails hammered into the block of wood at haphazard angles, perhaps representing separate trees in a forest. In the first case, removing a single nail would have the whole system collapse. Not so in the second. In the essay, he suggested that an uncritical celebration of biodiversity does not allow for a distinction between “useful” and “harmful” species, a perspective that could, for example, prevent the eradication of smallpox. He wrote that “the current denigration of the forestry profession can be traced to Leopold and his stories” and that ecosystem management, as a model, distracted foresters from “the cause of a sustainable environment.” He threw in some barbs and what I’m sure he saw as zingers, sharp lines that captured his sarcastic tone. Sometimes, it’s true, his jokes were lost in translation.5

The Journal of Forestry editors invited J. Baird Callicott, a leading environmental ethicist and scholar of Leopold, to write a response to Papa in the same issue of the journal. By any measure, his essay was full of invective: Zeide’s position was a “deliberate, unscholarly misrepresentation”; Zeide was a “disgruntled polemicist” with a “vision of the world [that] is arrogant, one of human domination.” Ooh, and the one that really got me as I read it, still reeling in the months after my father died: Zeide was “an exponent of the Rush Limbaugh school of argument.” It felt just mean, even when I was able to step back and recognize that many of Callicott’s arguments were sound, that he pointed out significant flaws in my father’s writing—that Papa set Leopold up as a straw man, that his real target was ecosystem management, that he came off as unnecessarily harsh. I didn’t really know what to do with the feelings these essays provoked in me, the mixed allegiances they stirred.6

That sense of extreme disorientation only continued as I read further into the Zeide v. Callicott debate in the follow-up April 1998 Journal of Forestry issue. There had been fifteen letters to the editor written about the January issue, along with the additional responses the journal had solicited from my father and from seven other men with various kinds of expertise in the field. (The gender dynamics from a twenty-first-century perspective are striking.) There was the letter from my dad’s boss asserting that his essay “does not reflect a position of the University of Arkansas.” Some letters bemoaned the Crossfire approach of the discussion, recalling the debate-style news show whose episodes often devolved into partisan hackery. One called my dad’s essay an “unworthy rant” and another a “bizarre polemic.” Still another considered it “an interesting and scholarly review of a philosophy that had become almost biblical in the conservation community.” The solicited responses were similarly wide-ranging. The final response, from an Oregon State professor who worked for the epa, summed it all up this way: “What Zeide and Callicott are really debating is not the nuances of Aldo Leopold’s published words but the proper role of science and values in deciding ecological policy, especially under the rubric of ecosystem management.”7

The role of science and values in ecological policy. This captured what I was studying in graduate school as a budding historian of science and the environment. I clearly trod in my father’s footsteps, even if his specific ideas did not reflect my own. But I read his words against ecosystem management with all the layers of understanding of who he was and what motivated him. I understood that his tone, which others found so severe, was a product of his being an immigrant, reflecting both his Russian language and Russian culture. I knew that his one-liners trying to poke holes in Aldo Leopold’s views were of a piece with his general sarcasm. I read his not always balanced perspective as a part of his general isolation as a scholar in rural Arkansas who lived inside his own head most of the time, rarely finding among his colleagues interlocutors who could help him hone his arguments.

When J. Baird Callicott or Papa’s other critics read his words, though, they took them at face value. They offered what they perceived as a necessary counterattack, taking Papa’s essay as the initial act of aggression in a war they were determined to win. From my perspective as a grieving daughter, this felt unfair. Shouldn’t we try to understand scholars and their words as the result of many complex factors? How could they tear him down so maliciously? As a scholar myself, though, I knew that I did this all the time. That I read individual works of scholarship and celebrated or rejected them on the basis of nothing more than the words on the page. What else could we do? The ideas we have in front of us are those that are written and published, standing naked on their own terms, without the greater backstories and biographies that inevitably and invisibly cloak what lies inert on the page. That’s what we do. The ideas are everything.

But which one liked trees better?

These days, I’m a professor, living in a rural southern place, raising two kids whose notions of the world are already beginning to diverge from my own. As I wrote this essay, the five-year-old asked me what it is about. I tried to describe the debate between Papa and Callicott. She asked, “But which one liked trees better?” I paused, and then answered, “I think both of them, but maybe in different ways.” She resisted, crying, “No! Papa liked trees better! Papa is better!”

They know him only as the character in my stories, the man for whom trees were the ultimate friend. The person I idolized and who laid the path that I have followed. It’s too difficult for my kids—too difficult for me sometimes—to hold both that heroic characterization and the more complex reality.

I try to hold all these pieces together. The southern place that shaped me even as it socially isolated me, the woods that gave birth to my sense of environmental devotion even though the sky and trees were never enough, the father whose iconoclastic example gave me strength even as my commitments diverged, the scholarly approach to ideas that I have inherited alongside a sense that it does not do the creators of those ideas justice. The past and present, sandwiched together, balanced on a single nail. Pull one out and it all topples.

This essay first appeared in the Human/Nature issue (vol. 27, no. 1: Summer 2021).

Anna Zeide is associate professor of history and director of the food studies program at Virginia Tech. Her first book, Canned: The Rise and Fall of Consumer Confidence in the American Food Industry (University of California Press, 2018), won a 2019 James Beard Award. You can find her on Twitter @aezeide and at www.annazeide.org.NOTES

- John A. Kershaw Jr., Mark J. Ducey, Thomas W. Beers, and Bertram Husch, Forest Mensuration, 5th ed. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2016), xiv.

- Boris Zeide, “Another Look at Leopold’s Land Ethic,” Journal of Forestry 96, no. 1 (January 1998): 13–19.

- Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac (New York: Oxford University Press, 1949), 224–225.

- Boris Zeide, “The Science of Forestry,” Journal of Sustainable Forestry 27, no. 4 (December 2008): 345–473.

- Zeide, “Another Look,” 19.

- J. Baird Callicott, “A Critical Examination of ‘Another Look at Leopold’s Land Ethic,’” Journal of Forestry 96, no. 1 (January 1998): 23, 24, 25.

- Letters, Journal of Forestry 96, no. 4 (April 1998): 1, 45–48; Robert T. Lackey, “The Legacy of Leopold: A Patch of Common Ground,” Journal of Forestry 96, no. 4 (April 1998): 33.