I.

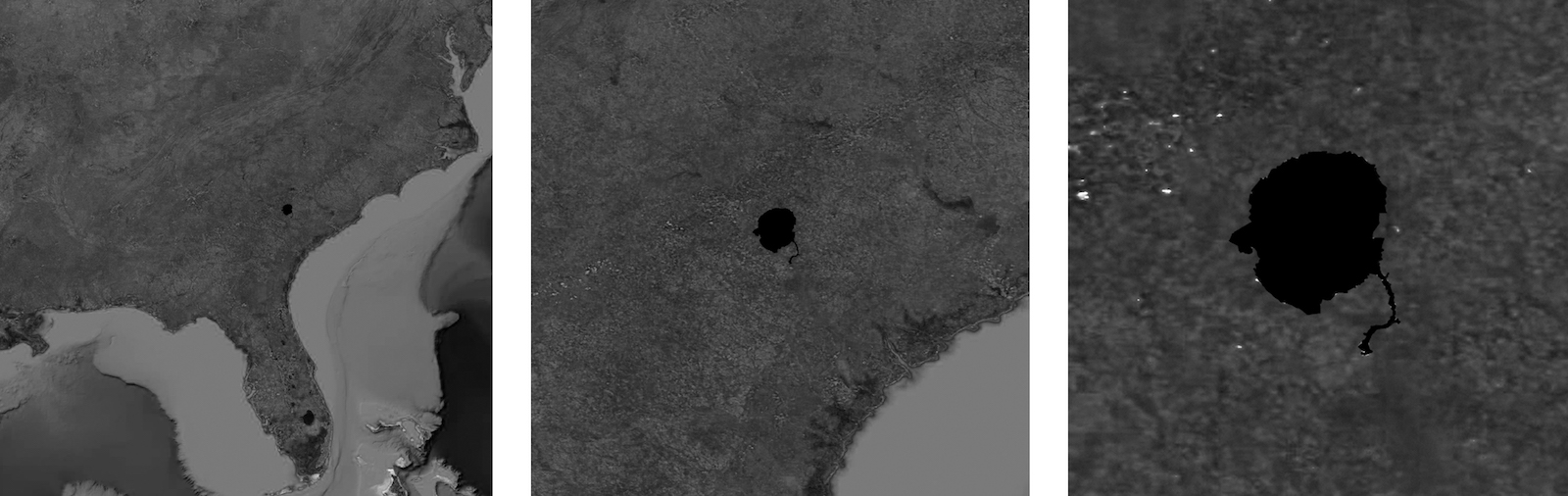

The K Reactor at the Savannah River Site (SRS) sits on the eastern bank of the Savannah River, facing west over six miles of woods and swampland, which remain uninhabitable for humans. The reactor is now a tomb for thirteen tons of plutonium, the highly radioactive fuel—and deadliest substance known to us—that powers hydrogen bombs. The plutonium lies inside, encased in steel canisters behind seven-foot-thick concrete walls. The four other reactors on site have been cast in concrete from a void in their own images from the inside out, calling to mind the poetry in Rachel Whiteread’s 1993 public sculpture, House, a hulking, brutal mass cast from the interior of a Victorian home. The final step in the decommissioning process was to fill these nuclear reactors entirely with cement, transfixing them into impenetrable blocks.1

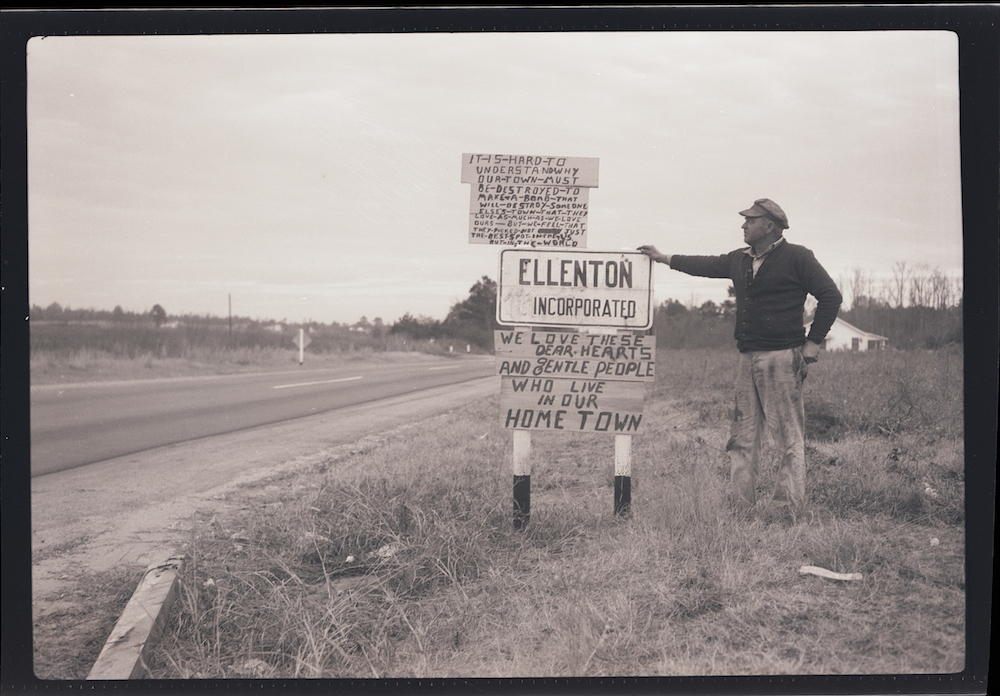

SRS, owned by the US Department of Energy (DOE), spans over three hundred square miles and is considered to be one of the most toxic sites on Earth. Construction on the site, originally named the Savannah River Plant, began in 1950 when the Atomic Energy Commission (now DOE) seized about two hundred thousand acres in South Carolina. The facility is just southeast of Augusta, Georgia, near Aiken, South Carolina. Fifteen hundred families were given just over a year to leave their homes and farms behind, the promise of fair compensation left unfulfilled. Towns like Ellenton, Dunbarton, Meyers Mill, and Leigh were razed. SRS would go on to produce roughly 40 percent of the plutonium used in the world’s Cold War weapons. The steel canisters produced to hold the waste are projected to last fifty years. The half-life for Plutonium-239, the isotope of plutonium produced at SRS, is 24,100 years.2

For House, Whiteread made a complete concrete casting of the insides of a late-nineteenth-century house in East London, after which she removed the exterior: windows, walls, and doors. The house was typical of the neighborhood, an East End family home later dubbed an eyesore, but its inverted details made the familiar shapes uncanny. Window panes jut out at unfamiliar depths and moldings make incisions cutting through the concrete. It commemorated no event and no singular person. Rather, the work is about spaces lived within, maybe as a survival of the Blitz or an embodiment of some stubborn hanging on. Slated for demolition in the early 1990s like the rest of the homes on its block, House is a structure’s last gulp for air before becoming a memory itself. Alone on the block against grey skies, it feels impossibly desolate, like some sort of frozen specter. All that remains of the work are photographs; the “monstrosity,” as it was deemed, was demolished after just eighty days due to public outrage.3

In an ontological sense, everything begins and ends with the void. Pure nothingness, an empty space of potentiality. The void is a zone of unknowing. SRS is unlivable territory, censored from the rest of the landscape through a private security force, gates, and thick groves of pine trees. How much of potentiality is arrested in fallout? What endures in the nuclear hangover?

If House, with its un-openable doors and unlivable rooms, imprinted with worn moldings, anonymous evidence of lives lived, was a monument to forgotten pasts and prior loves, maybe it can aesthetically inform how we read SRS‘s K Reactor, itself sealed, dense, and monumental. The reactor holds the invisible yet still seeping proof of a transnational, multispecies displacement, acutely toxic in a region where dispossession feels endemic: a monument to local ecosystems and landscapes now fused with the American nuclear project. Maybe, though, it is more helpful to read the reactor as a marker, a sign, or a warning of the leftovers of empire and their duration beyond what might be possible to imagine.

The K Reactor is a material node of a largely invisible and intangible nuclear legacy. Waste and the effects of radiation can be difficult to trace due to their delayed effects, immaterial properties, and impacts on less politically powerful communities. Furthermore, the visuality of nuclear sites, much like army bases and prisons, is tightly controlled, giving the common perception that they exist on the periphery, away from publics. However, this is due in part to how American nuclear sites often neighbor marginalized communities.

Nuclear complexes in the American West fit models of internal colonialism sketched by nineteenth-century expansionism. “Nuclear colonialism” is a term now used by Indigenous people who decry the use of their lands as nuclear waste repositories and test sites. During the twentieth century, throughout the West, the US Army colonized local communities in support of war projects and national security.4

At SRS and DOE nuclear sites across the US, the traditional logic of national security is inverted, and the threat of foreign weapons is replaced by language around internal territorial colonization and long-term stewardship. Enemies abroad are substituted for the monster we made: nuclear remediation will cost more than the Cold War arsenal itself. Here, we must conceptualize “remediation” not in the traditional sense of reversal, but instead as mere containment.5

In the 1950s, for many of the Black residents living on land expropriated to build SRS, which was known to locals as “the bomb plant,” discussion of fair compensation meant nothing in the moment. The effects of Jim Crow were compounded; whites owned almost all of the land rented to Black tenant farmers. SRS sits on both Aiken and Barnwell counties in South Carolina. Barnwell County in particular has a median income much lower than the state average, and its proportion of Black residents exceeds the state average by nearly 19 percent. The same can be said for Burke and Screven County, Georgia, which sit directly across the Savannah River from SRS and have historically suffered from the effects of SRS and the nearby Vogtle Nuclear Power Plant, consequences of a trifecta of the American imperial project, social histories of redlining and environmental racism, and the ruthlessness of capital.6

Black nationalist programs in the midtwentieth century already considered the core of the Black Belt South (South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana) as the base territory of the Black nation, often theoretically situated as an internal colony. Pervasive institutional racism was viewed as a form of colonialism, best exemplified through restrictions on Black people’s political and economic power, and the DOE’s decision about where to situate SRS rested, in part, on a belief that it would be easy to dislodge Black people from the land. SRS exists as a void and hulking monstrosity, its boundaries drawn and maintained by the doe as a toxic forever-ward of the state. It pushes lineages of human dispossession forward indefinitely. Furthermore, it is as acutely toxic to the communities around it as it is a problem at the planetary scale. SRS links the racialized (and militarized) displacement and voiding of communities and histories in the American South to global histories of territory acquisition and colonialism. The ground there is deceptively stable, but there can be no full reparation and certainly no return.7

Broadly, spatial histories of nuclearization in the American South illustrate that Cold War facilities and military contracts brought far more than jobs to the region. These contracts and installations had the power to remake entire economies. Along with modernization, this new workforce created by the federal government had cultural tastes and political allegiances that changed perceptions of the South. In the case of nearby Aiken, South Carolina,SRS brought new residents and new jobs that allowed the town to see itself as a modern, progressive community. The arms race incorporated the industrially stunted region into the modern nation state, playing an important role in the creation of a “New South.” As historian Kari Fredrickson writes, “The arrival of the military-industrial complex into underdeveloped Southern communities helped the region to overcome some of its more unsavory attributes. The Cold War made the South less ‘Southern.’” Frederickson defines “southernness” by a stunted, colonial economy, one predicated on low-wage extractive industry run by entrenched elites. She describes how future political leaders returned to the region after WWII, convinced that modernizing the postwar southern economy could happen via a large federal bureaucracy. But, modernization-via-militarization was the cynical project of the military industry working hand in hand with southern political leaders to take a hardline anticommunist stance, and in doing so exploit Black communities.8

Though the drainage properties of the site’s sandy soil and the water quality of the Savannah River played a role in where to locate the plant, its “southern” attributes made it all the more compelling. South Carolina had notably low construction wage rates as a result of the state’s antiunion fervor and historically weak labor movement. Atomic Energy Commission officials also noted that those living on the land of the proposed site were Black tenant farmers. Removing them would be easier than at other locations where property values were higher, according to a 1950 report from the Special Committee of the National Security Council to the President. The tenant system in the South was an economic trap for historically vulnerable rural Black residents that the federal government exploited. The complex mechanisms at the highest levels of the national security state include an attentiveness all the way down to how a captive Black population can be exploited in their regional context to expand the arms race.9

In comparison, the secret and planned city of Oak Ridge, Tennessee, known for producing enriched uranium and plutonium for the Manhattan Project, was selected for its geographical seclusion, access to electricity through the hydroelectric dams at the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), and the abundance of low-wage labor. Landowners were largely subsistence farmers, and the region was known for fighting for the Union during the Civil War. In 1942, the US federal government condemned the farms and gave residents two to three weeks to vacate their homes, crops, and livestock. Similar to residents living on land expropriated to build SRS, they were not paid enough to replace their farms, nor were they provided funds for relocation. The Oak Ridge plant enthusiastically recruited Black workers due to their high unemployment rates. Though the area was not segregated previously, the federal government segregated Oak Ridge and intentionally designed substandard housing for Black workers and residents, often called “built-in slums.”10

The history of anticommunism, much like the history of SRS, cannot be disentangled from a history of race. The Cold War facilitated and perpetuated the effects of white supremacy on a new foundation, simultaneously in de facto defense of colonialism and in opposition to communism, a movement that was principally opposed to the entire existing system of nation-states. Anticommunist passion during the Cold War integrated the segregationist South into a “historical bloc” in which southern state leaders played a critical role as anticommunist militarists. Southern politicians and industry leaders were by far the most committed and aggressive component of the Cold War anticommunist bloc in the United States. By the early 1970s, the twelve southern states provided the pentagon with 52 percent of its ships, 46 percent of its airframes, 42 percent of its petroleum, and 27 percent of its ammunition, securing a vastly disproportionate amount of government contracts from the rest of the states in the country. For residents and political leaders in South Carolina, a staunchly anticommunist foreign policy made more than just economic sense: it also spoke to their desire for a specific kind of progress, modernity, and a place within the nation.11

Theories tying together communism and civil rights were furthered by agencies of the federal government, such as the FBI and the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee. For example, the FBI labeled Martin Luther King Jr. and his allies in the Civil Rights Movement as part of “Left-Wing Pro-Communist Groups” who menaced the social order. The state was an integral component of anticommunist systems in the US, made up of the federal government, southern state leaders, and groups in civil society. These theories also appeared in propaganda published by the Ku Klux Klan in the 1960s; Klan leaders make it clear that they too believed that communism was responsible for the Civil Rights Movement, and added that it would bring “racemixing” to the South. In 1963, a flyer published in Georgia by the United Klans of America showed a photograph of a biracial crowd of children playing in a park under the headline “Are these your children?” Below, it lists “facts” related to recent civil unrest predicated by “the Communist Party” and “Martin Luther King’s organization.” In this context, SRS, and in particular the K Reactor, can be read within a regional history of twentieth-century white supremacist monuments that sought to enforce a racist social order through intimidation and denigration.12

II.

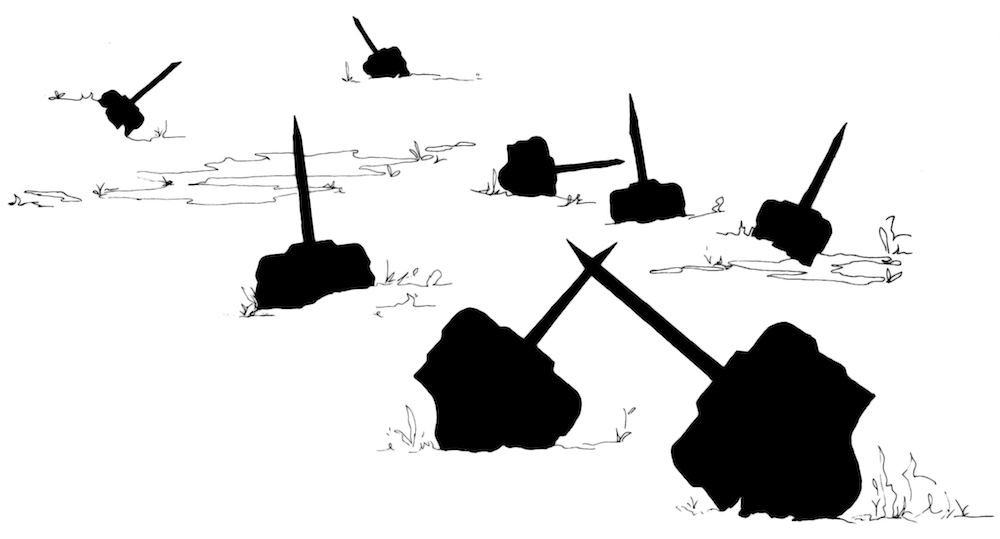

The field of nuclear semiotics arose in 1981 when the DOE and Bechtel Corp convened the Human Interference Taskforce, a team including nuclear physicists, anthropologists, and behavioral scientists. They were tasked with designing warning signs and markers to deter human intrusion into Yucca Mountain, a proposed deep geological nuclear waste repository in Nevada. To store highly radioactive nuclear waste, we must both contain it and maintain that it will not be disturbed for ten thousand to twenty thousand years.13

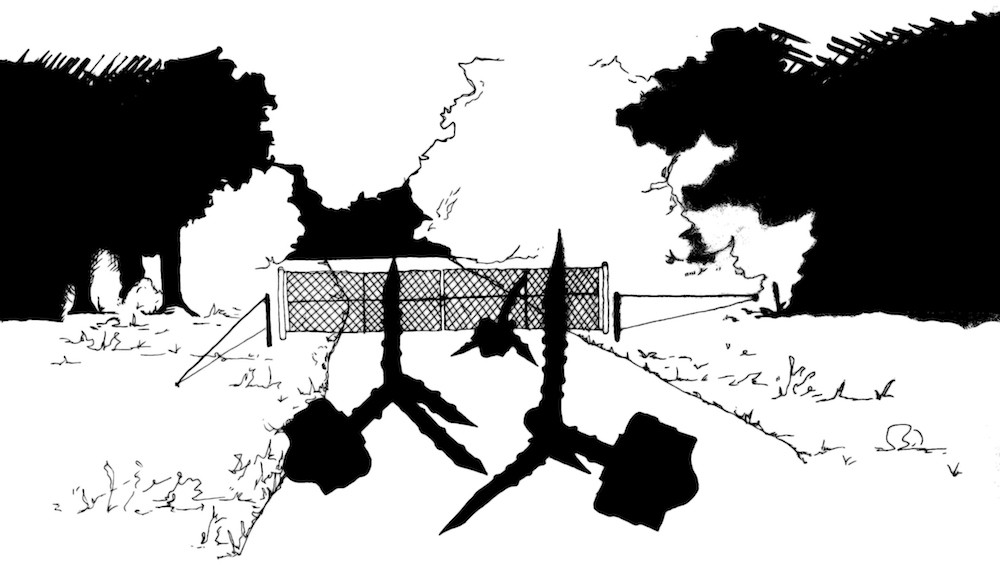

In 1996, the DOE, this time with Sandia National Laboratories, managed by a Lockheed Martin subsidiary, again convened a group of scientists, anthropologists, and artists to design markers for the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, another proposed deep geological nuclear waste repository, outside of Carlsbad, New Mexico. In one subsection of the report, “Expert Judgment on Markers to Deter Inadvertent Human Intrusion into the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant,” environmental designer Michael Brill and others on the panel came up with marker proposals with titles like “Forbidding Blocks” and “Landscape of Thorns,” constructed of “shapes meant to hurt the body and communicate danger” from materials like basalt and granite. These markers, meant to warn against unintentional human interference, took the form of monumental landscapes, colossal forms dominating vast swaths of land. The reasoning was that even if you were unable to communicate a discrete message, a landscape’s menacing disposition, marked by looming spikes or rubble, would be unsettling enough to dissuade those who stumbled upon it.14

Though some Roman concrete has endured from around 150 BCE to today, the K Reactor likely will not outlast the half-life of the plutonium it contains, long enough for its unsettling form to caution those who might encounter it. The expected lifespan for industrial concrete in underground nuclear waste repositories is five hundred years if the concrete does not freeze or thaw or come into contact with leaching water, just two of many possible variables which would shorten the concrete’s lifespan. The Savannah River Site itself is a massive environmental problem; classified by the EPA as a Superfund site, it stores thirty-four million gallons of high-level radioactive waste. Yet, it exists within a uniquely modern contradiction: despite the toxic and deadly nuclear hangover (a symptom of a markedly American forever-war machine) that yawns open in front of us, echoing into the next however many thousands of years, SRS has been publicized by the nuclear state as an ecological reserve preserved in time.15

I went on one of the few tours offered every year at SRS. Entering SRS feels a bit like driving onto an army base. To take a tour, you must be a US citizen and provide two forms of proper identification at the badge office, before your reserved time. The Department of Energy contracts a management company, Savannah River Nuclear Solutions, to maintain SRS and a private paramilitary for security services. During the bus ride through the site, our guide talked about the site’s biodiversity, responsible pine logging, and the safety brought by annual deer hunts “intended to lower the incidence of animal-vehicle collisions on the site.” (Similarly, media attention paid to the Chernobyl zone suggests that the territory has returned to a state of natural order: tour agencies promote the zone as a preserve teeming with wildlife.) Woodsy, almost kitschy, Smokey the Bear-esque signs remind drivers of the dangers of wildfires. Other signs encourage motorists to fasten their seatbelts to “further their lives.” These are not the warning signs I expected to see here. It’s all by design that you could traverse the site six ways to Sunday and not see one trefoil. Aside from the guards and checkpoints, it’s all so palatable, excruciatingly ordinary.16

On this tour, I was given a small first aid kit and a bottle of hand sanitizer (which, granted, means something different now than when I first toured the site in February 2020). If it’s raining, the guide might remind you that the bus stairs are slippery. There is a lot of talk of safety here, where 40 percent of the world’s Cold War plutonium was produced, but mainly the type of safety that prevents slip and falls, or at least releases SRS from liability if you eat it on the steps. These public relations moves to rebrand the site stand in stark contrast to how former SRS employees remember safety. Across demographics, they recall the pressures to keep silent about their exposure, the difficulty in obtaining exposure records, and how company surveillance led them to understand their employer as deceitful. Plant officials insisted the facility was safe, attempting to dismiss concerns even as evidence of death and illness from hazardous materials grew. Contaminated waste was dumped into unmarked pits with no safeguards to prevent it from seeping into groundwater.17

Everyone was downwind, but not everyone was downwind equally. Studies show us that female workers were less likely than males to be monitored for occupational radiation exposure, and they were also more likely to have incomplete dose histories that would hinder compensation for illnesses related to these exposures. Black workers were more likely than non-Black workers to have a detectable radiation dose and to experience higher incidents of some cancers as well as early deaths.18

In the mid-1980s, when DuPont still operated SRS, critics questioned the adequacy of monitoring and safety standards. In response, DuPont promoted, rather than tested, the efficacy of their current practices. This comes as no surprise. Their focus on confirming workplace safety for the sake of public relations, not worker health and well-being, fits a pattern. Nuclear work demands secrecy and a closing of ranks as it tangles with discourses of duty and patriotism.

The US military met civilian protests of destruction at military sites across the country in the 1960s and 1970s with claims that their properties inadvertently created animal sanctuaries endangered by civilian land practices: conservation by serendipity. Abundant wildlife shows up again and again in militarized environments; war zones and buffer zones between warring states seem to suggest that sometimes human conflict is a blessing for nonhumans. Certain Cold War frontiers (such as the DMZ) surprisingly became nature reserves, but, by the early 1990s, 81 percent of US federal facilities on the National Priorities List for waste cleanup belonged to the military. Moreover, at the end of the Cold War, the US military faced a crisis of legitimacy: how could it justify continued occupation of millions of acres of national land? Here, military environmentalism serves as a way to legitimate control over the territory. These transformations are not so much a way of turning the US military “green” but, rather, a way to repackage the war arm of the US in eco-friendly wrapping. For example, functionally obsolete US military bases can be converted to reserves in accordance with the Base Realignment and Closure process, which began in 1988. This allows the DOD to spend less on decontaminating the most heavily polluted lands, ultimately undermining potential benefits to wildlife. NATO facilitated a transnational network of military environmentalism post–Cold War, including environmental policy statements that encouraged soldiers to “train green.” Though NATO signatories, including the US, have begun to introduce recycling, reduce carbon emissions, and develop “green weaponry,” the life-enhancing aspirations of sustainability initiatives and the deadly objectives that serve as the foundation for military purposes are fundamentally at odds.19

This being said, a reading of military environmentalism at SRS would be incomplete without understanding how nonhuman life exists at the site, perhaps in opposition to human and military territorial control. Upper Three Runs Creek, which originates near Aiken, South Carolina, runs nearly two thirds of its length through SRS before joining the Savannah River. It is the most species-rich stream in North America, and the second-most in the world. Studies from the 1970s and the 2010s have shown that thirty-plus years of continued use by the Department of Energy has not had a detrimental impact on the creek. There is no data to compare the state of Upper Three Runs Creek before it was seized by the Atomic Energy Commission, when it would have been surrounded by farmland. According to the National priorities List Site Narrative for SRS, which established SRS as an EPA Superfund site, a small quantity of depleted uranium was released in January 1984 into Upper Three Runs Creek.20

III.

I wasn’t expecting the SRS bus tour to remind me of tours I’ve taken of plantations and historic houses in the South. In fact, the SRS tour fits neatly alongside other manifestations of heritage tourism in the region. These tours reveal how we negotiate past and present, and far too often, there is celebration of moonlight and magnolias and the containment (if not outright denial) of the site’s horrors. The South is continually deployed for profit, whether for haunting or reveling. But unlike the imaginary “Old South” presented on plantation tours, the primary narrative at SRS advances the “New South” of modernization and economic development. Noticeably, at SRS and these former plantations, the landscapes have been ideologically (if not also anthropomorphically) reconstructed from sites of labor, extracted by violence and coercion, to sites of leisure. They allow visitors to participate in a comforting narrative that makes sense of a cruel history, one that implicates them, without having to come to terms with the material reality that sustains it. History is resolved, buried and done with, but the relics are dusted and tidy and neatly arranged for our viewing pleasure.

Yet, a future nuclear apocalypse is not some wavering vision just beyond the horizon, deterred by weapons or deferred by politics. It is not a fear that haunted those in the past, relegated to the history books at the end of the Cold War. Rather, it is one we have inhabited since July 1945. After the first successful detonation of a plutonium bomb at the Trinity test site in New Mexico, we entered a postnuclear environment of our own making. The militarization and nuclearization of three hundred–plus square miles of swamps, Spanish moss, cicadas, and steel occupied by SRS not only triggered a process of re-wilding, but now must be maintained, for there is no fixing this nuclear problem. We will have to stay on nodding terms with it for more than twenty thousand years.

For me, living in the South means to often fall in and out of time, for our history here is not just deeply formative but impossibly present. Just as I reside within the region’s heavy history, it also resides within me—that whole thing about gazing into the abyss and it gazing back. If my own past is bound so inextricably to the history of this place, how do I reconcile that with how white people in the South so often recall and represent the past inaccurately? It is true, despite geography, in the words of theorist Andreas Huyssen, that remembering is always entangled with forgetting, and our memories are “always transitory, notoriously unreliable, and haunted by forgetting,” but there is something sinister in the way we white southerners fail to recollect what actually happened here, who planted all these fabled magnolias. Nostalgic white southerners invested in ahistorical visions of the region’s past seem to be longing for both return and absolution, but not a true reckoning, as BIPOC southerners have long advocated. The “New South” that trickled out of SRS brought modernization, but for whom, and why, and at what cost? Faulknerian visions where property rights and resource extraction undergird race and violence, the anachronistic architecture of our universities, plantations turned right into prisons or military bases—all reach back with a threatening nostalgia for an antebellum South that did not endure in reality as long as it has in corrupted imagination.21

The fate of the South, from colonial settlement to the transatlantic slave trade to the Cold War and SRS, is inescapably bound up with an international geopolitical context through material and durational entanglements. How can our relationship with time—slippery, and bobbing up and down in waves of what was and wasn’t—contend with a scale as massive as twenty thousand years? All I know for sure is that it exists outside of a humanist approach to time itself. Different from what we were taught to imagine—a spectacular, and cinematic, mutually assured destruction—the nuclear apocalypse plays out daily in background radiation, bodies, biospheres, watersheds, wildlife, and sacrifice. Yet, this new kind of nature, one marked by the dispersal of nuclear materials into the environment, is wild and mutant, diffuse and discrete; radioactive tumbleweeds and toxic alligators weave beyond state control, past the fences, gates, signs at not just SRS, but Los Alamos, and Trinity, and Hanford, and Carlsbad, and Oak Ridge, and Yucca Mountain, and, and, and.

IV.

The warning signs to keep trespassers out deflect from the reality that these sites might trespass on us, that they cannot keep all of the effects of the site in, despite public rhetoric of containment and security. This rhetoric leans heavily on commemoration of patriotism and language of honor and duty to communicate not only authority but deference to a greater good.

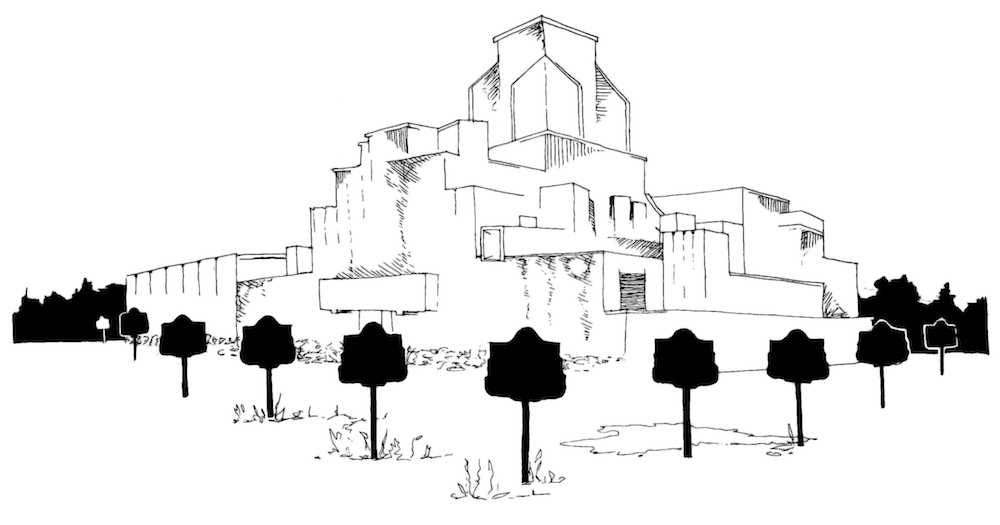

To understand SRS as a commemorative landscape as well as a proposed ecological reserve and militarized landscape, we must approach it as distinct from geological topography: landscape is a process. Constructed spaces represent and enact popular ideas about our imagined pasts and futures. Specifically, we can look to historic South Carolina roadside markers memorializing and historicizing SRS. We can investigate how what these markers say (narrate a particular story about the land) distracts us from what they do (use that narrative to advance a particular political and social agenda). These roadside markers retell history through their structural properties and textual references. Yet, they are able to convey the appearance of an official history through their relative lack of ornamentation, compared to most monuments and memorials. In the case of these markers, ideology attaches a normative component to aesthetics, meaning that the markers adopt an unmediated voice. This voice uses facts from one possible version of history to cast subjective preferences as objective and legitimate. On the other hand, monuments of conquerors make their agenda clear through sculpted bodies towering over publics, declarative epigraphs, and positions in high-traffic public spaces. The unadorned, state-sponsored aesthetic of peripheral highway historical markers, and their ubiquity, enhances their rhetorical power, marking these as official narratives and perhaps flattening historical and political complexities.22

The four South Carolina historic markers located at SRS commemorate the reactor with the best safety record (P Reactor marker); the largest reactor with six hundred positions for fuel rods and control rods (R Reactor marker); the first detection of a neutrino, a subatomic particle (Savannah River Plant marker); and the location of the former Ellenton post office (site of Ellenton marker). Two of these four markers, the P Reactor marker and the R Reactor marker, were erected in 2008 and sponsored by the US Department of Energy, with the expressed intent of “commemorating the role both reactors played towards winning the Cold War.” The language used on both is exemplary, focusing only on the highlights of each reactor. These two markers are located on roads only accessible to employees and officials with issued credentials.23

At the stoplight just a few tenths of a mile north of one of SRS’s main credentialed entry points, the Savannah River Plant marker sits among a constellation of RV park advertisements, a speed limit sign, a ground-level doe billboard, and a sign marking the boundary of US government property. The ground underneath the marker, erected in 2004 by the Aiken County Historical Society, was once paved, but it’s mainly crabgrass and litter now. The text lays out the plant’s significant role in national defense during the Cold War, then relays scientific anecdotes relating to the site after mentioning how its creation required “moving all residents from their homes.”24

The last reactor at SRS was shut down in 1992, and the Cold War Preservation Program at SRS began in 1997. The National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 is a federal law that requires all federal agencies to consider the impacts to historic properties in all their undertakings. The Cold War Preservation Program in part works to ensure compliance with NHPA; part of this process required that they survey 732 facilities in 2002.25

A granite plinth dedicated to “the families who originally lived on this property and to the patriotic men and women who have made possible the safe operations and successful missions” of the project lies in an overgrown garden off of Atomic Road, which bisects the western part of SRS. The benches near that plinth, which was erected in 2000 to commemorate fifty years of SRS, are so thickly covered with lichen that it’s difficult to imagine anyone sitting on them. By the road, a few yards from the monument, stands the Site of Ellenton marker (erected in 1993 by the Ellenton Reunion Organization). The marker, at the former location of Ellenton’s ca. 1873 post office, describes how the town was chartered in 1880. It simply states how the town and surrounding area were “purchased by US Govt in early 1950s for establishment of Savannah River Plant.” Every year since 1972, displaced families from Ellenton have gathered on the second Sunday in June to remember the town they lost.26

Atomic Road itself is dotted with signs telling motorists that they are not permitted to pull over, stop, or get out of their car. At the monument viewing area, there are two parking spots and a large sign that prohibits picnicking and camping. Per signage, parking is only allowed for those viewing the marker.

SRS markers illustrate a fictional history of linear progress and success, though all four were erected between 1992 and 2008: nearly nominal sacrifice for the greater good. Forced dispossession, in its many forms across species on irradiated soil (which has seen slavery and genocide, too) becomes interchangeable with patriotism. For SRS employees, staying quiet about radiation exposure and the doe’s illegal dumping is framed as a duty. Those who speak out risk that their employer will surveil them and their families.27

These signs, through their scale, materiality, and language, are supposed to convey authority, assure us that here on this land is history and we are on the correct side of it. But at the same time, they are dirty, the markers wave in the wind, and they contain far too much text to be read while driving on a road where it’s illegal to stop and read them. It’s almost like the signs know they’re just a bluff. More is at stake than just bad sculpture—how we memorialize our past says much about what we envision ourselves to be—they also feel utterly inconsequential.

Here, no Michael Brill–embodied landscape of granite thorns warns us of future and present danger, or reminds us of the lineage of displacement at SRS. (This line reaches out, far beyond South Carolina and the Savannah River and the South, to sustain the American war machine, dropping bomb after bomb to disappear towns not unlike Ellenton or Dunbarton. In doing so, the line profits companies like Bechtel and Lockheed Martin as they secure government contracts to contain the effects of the bombs they helped to build.) The markers do nothing to deter human intrusion. At best, they are false platitudes that ignore srs’s fraught history, from its effects on Black tenant farmers all the way up to the motivations for and repercussions of the arms race at the highest levels of government. At worst, they make sense of a story that never did.

Quantum physicist Karen Barad writes that when US forces dropped the first nuclear bomb on Hiroshima at 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945, “time died in a flash.” Not only did the splitting of the atom reconfigure global-scale geopolitics and destroy entire cities, but it shattered nested notions of scale (building < neighborhood < city < state < nation) and anything like an ontological commitment to differentiating between “micro” and “macro.” If an atom’s tiny nucleus, one hundred thousand times smaller than the atom, a near nothingness, results in incalculable devastation and uncountable deaths, then any presupposed concept of scale is fully blown to bits. The nuclear flash, hands of time moving and no longer moving, lays bare that time is unstable, continually leaking away from itself. For Barad, “Each moment is a multiplicity within a given singularity. Time will never be the same—at least for the time-being.”28

Instead of safeguards, what we get is an atomic House, the K Reactor surrounded by barbed wire and rubble, a fatalist reminder of what we lost in the throes of a nuclear psychosis, of the bed we made and now must lie in together. House, despite being a memorial to memory, was reduced to dust early because some thought it was monstrous. But the sculpture, although structurally stable, was inevitably always the pre-trembling of the fall itself. It was about loss, and so it was.

As we come to understand our current geological age, the Anthropocene, as a process-state at the edge of geo-history or, in other words, an always being-towards-death, the K Reactor is in its own pre-trembling. The flimsy aluminum historic signs, hard but ultimately hollow, only half-heartedly ask us to believe them. Together, they offer a solemn warning, but only if we know how to look for it. They certainly do not protect us, nor can they offer us an alternative to the ubiquity of violence. Their origin—a project of dispossession cloaked in patriotism—precludes that.

Maybe, though, the signs’ hollowness, or their seemingly perpetual dampness, or the potentially radioactive lichen growing over their text, making and unmaking history and time, offer an argument against a temporal certainty. The emerging polemic is a defense of an un-knowing about what once was or is or might come next, not because of a position in an empire but in spite of it. A mutant ecology’s own détournement.

This essay first appeared in the Built/Unbuilt issue (vol. 27, no. 2: Summer 2021).

Annie Simpson, a multi-/inter-/un-disciplined artist, was born in North Carolina and is currently an MFA candidate at the University of Georgia. She was a 2019 Monument Lab Fellow (as part of Take Action Chapel Hill) and has forthcoming exhibitions with the Goethe-Institut North America. She has exhibited recently at the Carrack (Durham), Purdue University, the University of Georgia, and the University of North Carolina.NOTES

- Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 209.

- Doug Pardue, “Deadly Legacy: Savannah River Site Near Aiken One of the Most Contaminated Places on Earth,” Post and Courier, May 21, 2017, https://www.postandcourier.com/news/deadly-legacy-savannah-river-site-near-aiken-one-of-the-most-contaminated-places-on-earth/article_d325f494-12ff-11e7-9579-6b0721ccae53.html; Gene Aloise, Securing U.S. Nuclear Materials: DOE Needs to Take Action to Safely Consolidate Plutonium, GAO-05-665 (Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office, 2005), 7; Robert Alvarez, “Plutonium Wastes from the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Complex,” Science & Global Security 19, no. 1 (2011): 17–18.

- Richard Shone, “Rachel Whiteread’s ‘House’. London,” Burlington Magazine 135, no. 1089 (December 1993): 837.

- Lucie Anne Genay, “The Scientific Conquest of New Mexico: Local Legacies of the Manhattan Project 1942–2015” (PhD diss., Université Stendhal Grenoble, 2015), 133.

- Joseph Masco, “Mutant Ecologies: Radioactive Life in Post–Cold War New Mexico,” Cultural Anthropology 19, no. 4 (November 2004): 530.

- Pardue, “Deadly Legacy”; “Barnwell County, South Carolina; South Carolina,” United States Census Bureau, July 1, 2019, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/barnwellcountysouthcarolina,SC/PST045219.

- Charles Pinderhughes, “Toward a New Theory of Internal Colonialism,” Socialism and Democracy 25, no. 1 (March 2011): 244.

- Kari Frederickson, “Creating a ‘Respectable Area’: Southerners and the Cold War,” Diplomatic History 36, no. 3 (June 2012): 488.

- Frederickson, “Creating a ‘Respectable Area,’” 488–489.

- Janice Harper, “Secrets Revealed, Revelations Concealed: A Secret City Confronts Its Environmental Legacy of Weapons Production,” Anthropological Quarterly 80, no. 1 (Winter 2007): 44–46.

- Richard Seymour, “Cold War Anticommunism and the Defence of White Supremacy in the Southern United States” (PhD diss., London School of Economics and Political Science, 2016), 131.

- Seymour, “Cold War Anticommunism,” 10, 235, 8.

- Thomas A. Sebeok, “Pandora’s Box: How and Why to Communicate 10,000 Years into the Future,” Media Arts and Technology, University of California Santa Barbara, accessed April 10, 2021, https://www.mat.ucsb.edu/~g.legrady/academic/courses/01sp200a/students/enricaLovaglio/pandora/Pandora.html.

- Kathleen M. Trauth, Stephen C. Hora, and Robert V. Guzowski, Expert Judgement on Markers to Deter Inadvertent Human Intrusion into the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, US Department of Energy & Sandia National Laboratories (Albuquerque, NM: US Department of Energy, 1993), F-57.

- Masco, “Mutant Ecologies,” 523.

- Kate Brown, “Chernobyl Mono-Cropped,” RCC Perspectives, no. 9 (2012): 53.

- Loka Ashwood and Steve Wing, “Worker Alienation and Compensation at the Savannah River Site,” New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy 26, no. 1 (2016): 60.

- Kim A. Angelon-Gaetz, David B. Richardson, and Steve Wing, “Inequalities in the Nuclear Age: Impact of Race and Gender on Radiation Exposure at the Savannah River Site (1951–1999),” New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy 20, no. 2 (2010): 195.

- Peter Coates, Tim Cole, Marianna Dudley, and Chris Pearson, “Defending Nation, Defending Nature? Militarized Landscapes and Military Environmentalism in Britain, France, and the United States,” Environmental History 16, no. 3 (July 2011): 465–469

- “Par Pond, Upper 3 Runs Creek–Savannah River Site, South Carolina,” SCIWAY, May 2009, https://www.sciway.net/srs-savannah-river-site/par-pond.html; Jennifer Gibbons, “Ecological Biodiversity on Savannah River Site Continues to Thrive,” Odum School of Ecology, University of Georgia, July 18, 2011, https://www.ecology.uga.edu/ecological-biodiversity-on-savannah-river-site-continues-to-thrive/; NPL Site Narrative for Savannah River Site (USDOE) (Aiken, SC: US Department of Energy, 1991), 2.

- Gibbons, “Ecological Biodiversity”; Andreas Huyssen, Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory, Cultural Memory in the Present (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003), 28.

- The first statewide programs to erect roadside historical markers began in the late 1920s, but the largest number of state-sponsored programs developed after World War II. In the decades following the war, American families took to highways on vacations, which had as much to do with recreation as it did with a desire to explore historic sites that reflected a patriotic national identity and forged a sense of good citizenship at the dawn of the Cold War. At the peak of America’s cultural and political struggle against the Soviet Union, heritage tourism propagated narratives that catered to middle-class white America. The vast majority of historical markers reinforce themes of all-knowing Founding Fathers, American exceptionalism, brilliant and strategic soldiers, and brave settlers on a local level by foregrounding residents (mostly white and male) and events that point to shared values with these midtwentieth-century, white, middle-class travelers. In 1954 alone, around forty-nine million Americans set out on heritage tours of the United States. Kevin M. Levin, “When It Comes to Historical Markers, Every Word Matters,” Smithsonian Magazine, July 6, 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/when-it-comes-historical-markers-everyword-matters-180963973/.

- “SRS History Highlights,” Savannah River Site, US Department of Energy, accessed March 2, 2021, https://www.srs.gov/general/about/history1.htm.

- “Discover Aiken: 10 S.C. Historical Markers to Know in Aiken County,” Aiken Standard, last updated November 9, 2020, https://www.postandcourier.com/aikenstandard/news/discover/discoveraiken-10-s-c-historical-markers-to-know-in-aiken-county/article_27830560-0cb0-11eb-a4c5-4bb-13bc1c415.html.

- Paul Sauerborn, “Cold War Historic Preservation Program,” Savannah River Nuclear Solutions, LLC (PowerPoint presentation, SRS Citizens Advisory Board Strategic and Legacy Management Committee, June 14, 2011), https://cab.srs.gov/library/meetings/2011/slm/20110614_historicpreservation.pdf.

- Samuel Ritchie, “That Others May Live: The Cold War Sacrifice of Ellenton, South Carolina” (master’s thesis, Clemson University, 2009), 78.

- Trauth, Hora, and Guzowski, Expert Judgement on Markers, F-57.

- Karen Barad, “No Small Matter: Mushroom Clouds, Ecologies of Nothingness, and Strange Topologies of Spacetimemattering,” in Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, ed. Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), G106–G109.