“‘Running this old printing press / with a woman on my mind / it jammed up tight eight times today / and I think this might make nine.'”

In the inaugural 1976 issue of the journal Sinister Wisdom, founders Harriet Desmoines and Catherine Nicholson wrote, “We’re lesbians living in the South. We’re white; sometimes unemployed, sometimes working part-time. We’re a generation apart.” Based in Charlotte, North Carolina, the women pledged “political action” to “think . . . keenly and imaginatively” about how to develop lesbian-feminist consciousness and emphasized that they were “using the remnants of our class and race privilege to construct a force that we hope will ultimately destroy privilege.” Many lesbian-feminists around the United States recognized Sinister Wisdom as a vital entry into the landscape of lesbian print culture, particularly after the demise of Amazon Quarterly, a national journal headquartered in Oakland, California, that ceased publication in 1975.1

We’re lesbians living in the South. We’re white; sometimes unemployed, sometimes working part-time.

During the 1970s and 1980s, lesbian-feminist books, shorter chapbooks, journals, periodicals, newspapers, posters, and broadsides were distributed across the United States through social networks, community organizations, and businesses. Locally, writers and publishers often circulated their goods hand-to-hand—selling, swapping, and sharing publications. The intent, as Desmoines and Nicholson expressed for Sinister Wisdom, was to challenge public consciousness and create materials for a lesbian-feminist revolution. Journals and zines proposed visions of a new world—one absent of sexism and homophobia where women and lesbians could live full, open lives, unencumbered by the oppression of hetero-normative patriarchy.2

Lesbian-feminism, as an ideology, was both a visionary and a practical expression of the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM), and lesbian print culture helped mobilize other women to share in its vision, philosophy, and activism. Although narratives of the WLM often focus on major urban centers, the movement flourished across the nation. In the early 1970s, for example, feminists in North Carolina organized a number of initiatives including the Durham Women’s Center (a project of the Durham YWCA), the Durham’s Women’s Health Collective, Peer Information Service for Counseling and Education in Sexuality (PISCES), and Triangle Area Lesbian Feminists. The burgeoning feminist community prompted a group, including Elizabeth Knowlton, to publish 3,000 copies of the Whole Women Carologue: A Guide to Resources for Women in North Carolina. Emphasizing women’s liberation, the guide included resources for health, athletics, law, and politics, among other things, and sold to women in North Carolina for $3.3

From this culture of organizing grew two lesbian-feminist journals: Sinister Wisdom and Feminary—the latter having begun in 1969 as a newsletter of the Research Triangle Women’s Liberation. The founding of these two journals in North Carolina demonstrates the vitality of local lesbian-feminist communities to launch and sustain projects of national significance. In addition to Feminary and Sinister Wisdom, three small publishers made their home in the Tar Heel State. Judy Hogan founded Carolina Wren Press in 1976 in Chapel Hill. While not solely a lesbian-feminist press, Carolina Wren illustrates the creative and artistic vibrancy of the region. Hogan was also a member of the collective that founded Chapel Hill’s Lollipop Power in 1969. This publisher and print shop issued non-sexist and non-racist children’s books. By the mid-1970s, it was a major operation, doing its own typesetting, printing, and design, and in 1975, Lollipop Power sold 1,500 books per month. Down the road in Durham, Night Heron Press emerged in 1981 as a vibrant cultural expression of lesbian-feminism, as well as a strategy to transform the material conditions of lesbians’ lives.4

Print culture was not the only thriving expression of feminism or lesbian-feminism in North Carolina. In 1976, three women started Ladyslipper, a mail order music distribution business in Durham. Ladyslipper was one of the two primary distributors of womyn’s music throughout the 1980s and 1990s and continues to operate today. These journals and businesses reveal vibrant lesbian-feminist communities in North Carolina, which enabled women to imagine and implement cultural projects that expressed the movement’s values.5

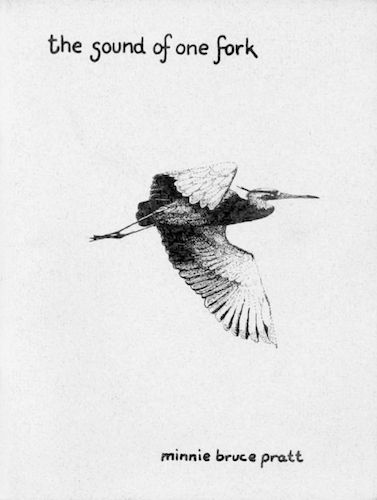

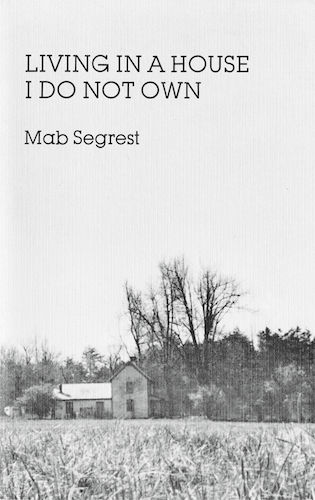

Night Heron Press: Two Chapbooks

Minnie Bruce Pratt, Cris South (a printer and Pratt’s lover), and Mab Segrest—who worked together as a part of the Feminary Collective—came together to launch Night Heron Press. Under that banner they published two chapbooks (small, inexpensively produced booklets, often bound with staples or hand stitching): Pratt’s The Sound of One Fork (hereafter Sound) in 1981 and Segrest’s Living in a House I Do Not Own (hereafter Living) in 1982. Both Sound and Living illustrate literary critic Alicia Ostriker’s observation that a “central project” of women’s poetry is “a quest for autonomous self-definition” and an exploration of “the conditions of marginality.” In their respective works, Pratt and Segrest explore these terms in two registers: as women and as lesbians. Living and Sound are similar in content and tone, considering lesbian domesticity and intimacy between women with particular emphasis on the authors’ experiences as southern lesbian writers.6

Sound opens on a river that Pratt knew well from her childhood in Alabama:

On the banks of the Cahaba

Black walnuts are scattered

With their smooth skins split

Down through convolutions

To the kernel fat within.7

With these lines, Pratt lays out her intention for the book: to expose the core of her life as a southern lesbian. To explore this terrain, Pratt grounds her poetry in imagery and language from the South, while simultaneously locating lesbian sexuality and desire in the poems. Pratt writes in “Occoneechee Mountain” about the “red-shouldered hawk” and “watching the ferns uncurl” and “the unfolding elm and trillium.” These images from nature operate as a metaphor of Pratt’s sexuality, particularly as a feminist and as a lesbian. Then married, she writes, “I conjugated only with Ovid and my husband,” but on the North Carolina mountain, isolated from friends and family, she “masturbated as unselfconsciously as Eve.” Pratt locates her poems in specific southern locations, simultaneously aligning these locations with classical references and imbuing them with lesbian-feminist sensibilities.8

In the poem “My Mother Loves Women,” Pratt connects her own woman-loving as a lesbian with the affectionate and friendly ties her mother builds with women through cooking, walking, and knitting. Pratt confides, “My mother loves women but she’s afraid / to ask me about my life. She thinks / that I might love women too.” In “Southern Gothic,” Pratt likens herself to two other “strange” women in her town who “wandered / like wolves in its streets hunting for the wildness / hung between the starched clothes stiff on the line.” She concludes by suggesting that the neighbors murmur, “how particular, how queer.” Pratt gestures ideologically to the lesbian-feminist manifesto, “The Woman-Identified Woman,” and to Adrienne Rich’s essay, “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence.” Pratt identifies her mother’s community of women as “woman-identified” and love for and relationships with women as part of Rich’s “lesbian continuum.” Through poetry, writers like Pratt engaged in a broader theoretical and ideological dialogue within lesbian-feminism. The poems in Sound also demonstrate Pratt’s increasing commitment to social justice issues, particularly anti-racism. Pratt expresses this commitment more fully in her later essay, “Identity: Skin Blood Heart,” from a collection titled Yours In Struggle.9

Through poetry, writers like Pratt engaged in a broader theoretical and ideological dialogue within lesbian-feminism.

Segrest’s chapbook similarly evokes the southern landscape of the area surrounding Durham as a space to explore feminism and lesbianism. Living employs two central tropes—the house and nature—as metaphors for her life as a lesbian. Segrest composed these poems over a year while living in a rented house on the outskirts of Durham. Living opens with a description of the beauty of the natural world and Segrest’s desire to connect with it:

One morning last summer spiders spun dew.

They decked the tree in webs.

I wanted to break off the branches

and bring them inside.

Like the branches that she wants to bring inside, Segrest brings lesbian experience into public consciousness. Segrest concludes the poem, “How to capture this glisten this quiver / carry light in a sieve / when I live in a house I do not own.” The central image of the house functions as a metaphor for Segrest’s life in the world as a lesbian. She lives in the world but does not own it; as a lesbian she is a tenant, not granted full rights of property ownership in a system that privileges heterosexuality.10

The emotions of Living are restrained. In “Plans for a Summer Garden,” she writes:

I will grow anger—

sweet and acid as tomatoes,

cool as cucumber,

sliced as thin.

Prickly as poke greens,

slick as okra.

I will give it in basketsto friends—

pickled, preserved,

with relish.11

Segrest uses the language of gardening and canning as a metaphor for anger, but the target of the anger is undefined. The emotion is diffused, even subsumed, through the omission of the referent and through the assignation of anger to vegetables in the garden. The natural world operates as both a veil and a platform for Segrest’s political vision. In “The Strawberry Capitol of the World,” Segrest writes, “I want to learn to live with fullness, / unafraid of summertime.” This couplet captures one of the intentions of both Segrest and Pratt: to live with fullness—to be open and unafraid of publicly expressing their lesbianism.12

Night Heron Press: Material Implications

In a grant application, Pratt wrote that Night Heron Press’s purpose was “to publish the work of Lesbian women, living in or linked to the South in some way, who have been denied access to more traditional means of publication because of their sexuality, race, class, ethnicity, or political point of view.” With this statement, Pratt situates the press as a part of a larger political agenda; as feminists, Pratt, South, and Segrest were committed to examining the interconnections of sexism, racism, and homophobia, particularly in the South.13

When the Press began, Pratt explained, it “[o]perat[ed] with the volunteer labor of three women, some donated use of equipment, no advertising budget, and cash spent only for the cost of materials.” Like other small lesbian-feminist presses, Pratt and South managed Night Heron on a shoestring, nurturing it more with time and commitment than money. Regardless of its size, however, Night Heron Press was doing well in 1982, having sold 2,000 copies of the two poetry chapbooks with “a third book in production.” Pratt wrote to her friend Elizabeth Knowlton in Atlanta that she hoped Night Heron Press would be integrated into “Cris’ business / copy center when / if that gets going.” For Pratt, Night Heron was one aspect of an imagined economic future with book publishing offering some revenue to support creative and political work. This never happened; Night Heron published and distributed only the two chapbooks, then ceased operations when the women moved on to other projects.14

Pratt describes publishing Sound “with a minimum of fuss and muss.” The entire process took about two months between early April and late May 1981, which included the time she spent selecting and ordering the final manuscript. Pratt says of her process that she put the poems “in a story / chronological order,” then Segrest “re-ordered them somewhat.” This process helped reveal some of the weaker poems in the collection. Pratt notes, “when I read them in her sequence it was clear that those three [poems] didn’t hold up to the rest. (I knew this but tried to hide them in chronological order.)” With the changes suggested by Segrest, Pratt edited the book and finalized it for typesetting.15

Pratt’s chapbook was a family affair. She writes to Knowlton, “When Ransom and Benjamin [her sons] were here they helped me finish the remaining 350 copies—folded covers, stapled and trimmed. They were wonderful—and so excited to be helping me and to be making books. Ransom said, ‘Lots of people read books, but not many people make them.’” In 1981, Pratt was a non-custodial mother; she documents the saga of losing custody of her sons to her ex-husband in her later collection, Crime Against Nature. Pratt’s delight in engaging her sons in producing the book is compounded when she finds Ransom reading the poems as he is stapling the finished books. He said, “Did you really drown a turtle? Why did he say no? Why were the rotten oranges in the refrigerator? Whose refrigerator was it? Is this the Anne I met last summer?” Pratt confides to Knowlton, “I almost wept with joy.” Ransom and Benjamin Weaver’s labor on Pratt’s chapbook brought the family closer together, literally enacting one of the visions of lesbian-feminism: enabling lesbians to be open about their lives. After the books had been trimmed, collated, and stapled, both Ransom and Benjamin wanted autographed copies and an extra copy to share “with selected teacher/friends.” This story demonstrates the powerful currency of books: they entice readers with their material incarnation and travel from reader to reader with their message safely printed inside.16

[Books] entice readers with their material incarnation and travel from reader to reader with their message safely printed inside.

Initially, Pratt distributed Sound herself with support from the local and national network of lesbian-feminists. Pratt sent a flyer out with the humor issue of Feminary in the fall of 1981. She noted that bookstores already ordering Feminary would receive it and “hopefully they’ll pick me up.” Pratt also sent out “publicity to women’s bookstores cross-country, and [tried] to get library journals to review it—so librarians will order.” Sound reached readers through the dint of Pratt’s labor: she traveled around the country doing readings and events in women’s bookstores, homes, and other feminist and lesbian-feminist spaces. Pratt recalls selling books out of the trunk of her car to readers, one by one.17

The first print run of Sound was 490 copies; Pratt distributed twenty to friends and a small number of review copies. Between 1981 and 1984, Night Heron Press printed 2,000 copies of Sound and sold them all. Pratt only printed 500 copies at a time because that is all she had enough money for—“even bartering with Cris.” The final printing of 500 copies cost “$600 for paper printing, collating, stapling, and trimming.” In 1982, The Crossing Press based in Trumansburg, New York, agreed to distribute both books from Night Heron Press; when The Crossing Press stopped distributing books, Sound was distributed by Inland. Distribution is a time-consuming business with a small profit margin, but publishers in the vibrant small press community of the 1970s and 1980s supported one another through distribution agreements like this collaboration.18

Although Pratt characterizes her circulation of review copies as judicious, Sound was reviewed widely in both the United States and Canada, demonstrating the extensive lesbian print culture networks in North America. Reviews appeared in Sinister Wisdom, off our backs, and Gay Community News. In a piece for the Canadian lesbian/gay newspaper Body Politic, Joy Parks wrote, “The poems in this small volume speak directly and, telling their story simply (the way one would tell a friend), bring truth and delight to the reader in the stark but moving language of women’s bodies and the Southern landscape.” Parks echoes the overall sentiment of lesbian-feminist poetry as confessional conversations between friends, and Parks’s review highlights the general reception of Sound: lauding Pratt as a poet who unites feminism with southern experiences. Pratt’s location in North Carolina and the contents of her poems marked Sound as an important elaboration of lesbian-feminism from a southern perspective, but the wide range of reviews indicates that Pratt’s perspective was important to lesbian-feminists in a variety of geographic locations.19

Jewelle L. Gomez began her review in the Brooklyn-based Conditions, “One reason for my lasting attention to a good writer is her subjective, unstinting use of facts and fantasies of her life in her work and the ability to create a kinship between them and my own. Minnie Bruce Pratt is such a poet.” Gomez reads Pratt’s work in a nuanced way. By noting that writers use both fact and fantasy, she subtly challenges the idea that lesbian-feminist poetry is only confessional. In addition, Gomez highlights a kinship between herself as an African American writer and Pratt as a white writer. Gomez continues, “[S]he writes from within a distinctive experience of oneness with her world, the American South, and at the same time conveys her sense of estrangement from its pervasive tradition of separate and unequal.” Gomez deems Pratt’s work significant because it emerges from the American South and challenges the history of racial oppression. The experience of both “oneness” with the world and “estrangement” provided a metaphor for lesbians living in a patriarchal culture as well as a metaphor for the broader issues of oppression as a source of struggle within lesbian-feminist communities. Projects like Sound served as a vehicle to elaborate the contours of lesbian-feminist identity in different locations; Pratt’s emerging antiracism in Sound provided a model for thinking about those issues within lesbian-feminist communities. Gomez’s choice to frame the review in relationship to questions about racial justice demonstrates not only insight into Pratt’s poetry, but also the publishing commitments of Conditions, which had just transitioned from the all-white founding editors to a new multiracial editorial collective.20

In the end, Night Heron Press only published Sound and Living, both of which are now out of print. Pratt selected a few of the poems from Sound for The Dirt She Ate: Selected and New Poems. Segrest hasn’t published poetry since Living, though her collection of essays, My Mama’s Dead Squirrel, narratively picks up on many of the themes of that work. Considering these two chapbooks as artifacts of Night Heron Press reveals opportunities that publishing offered lesbian-feminists. It provided a platform for Segrest and Pratt to promote their work and activism. In addition, the chapbooks enabled Pratt and Segrest, who both had recently completed PhDs in English Literature, to assert an intellectual life for themselves outside the academy. When Sound was published, Pratt was trying to organize her life in a way that provided her time and space to write without the demands of teaching as a lecturer at local universities; Pratt lived, in part, on the money from the sale of the chapbooks. Sound was a tool for her to do readings and lectures, which became an important source of personal income for her.21

As Pratt told Knowlton, Night Heron Press was part of a broader vision of a livelihood for South as a tradeswoman in printing. For South, as for Pratt and Segrest, the material conditions of printing intersect intimately with the ideals of lesbian-feminism. In a 1984 novel by South, Clenched Fists, Burning Crosses, the protagonist, Jessie, owns a print shop. The central plot revolves around printing materials for an anti-Klan protest; a subplot of the novel involves a battered woman in a shelter. These two storylines animate the actions of feminists to provide personal safety and security to individual women and to bring broader safety to the community through protesting the Klan. The mingling of South’s fictive narratives with polemical, feminist stories and her lived experiences in producing lesbian-feminist culture connects the material conditions between producing books and generating lesbian-feminist theories in the WLM. The theoretical was not abstracted from the material, nor was the material separate from the theoretical; the two were intertwined and co-constitutive.22

Sound and Living are representative chapbooks of lesbian print culture in the early 1980s. The poems within them, as well as their publication and distribution, tell a common story: lesbian print culture emphasized the empowerment of writers to publish their own work and asserted poetry as a medium of the movement.23

Lesbian print culture emphasized the empowerment of writers to publish their own work and asserted poetry as a medium of the movement.

While printing Sound, South wrote lyrics about being a lesbian-feminist printer. Her song begins,

Running this old printing press

with a woman on my mind

it jammed up tight eight times today

and I think this might make nine

there’s paper in the rollers

and solution down my sleeve

I just got here but I think it’s time to leave.24

By the mid-1980s, Minnie Bruce Pratt relocated to Washington, D.C., and Mab Segrest focused less on literary pursuits and more on her political work with North Carolinians Against Racist and Religious Violence (NCARRV), a progressive organization active during the 1980s and 1990s with broad national influence. Night Heron Press ceased to be.25

The energy that had coalesced around lesbian-feminism in the 1970s and early 1980s dispersed. Many lesbian-feminist activists directed their time and attention to other political movements with similar values and aspirations, including Central American solidarity work, a newly coalescing lesbian and gay movement, street-level activism to address and eradicate HIV/AIDS, health care activism benefiting both gay men and lesbians, and new and different struggles for women’s liberation and equality. Some feminist cultural production and distribution organizations shuttered while others continued, adapting to changes in the political, social, and cultural landscapes locally and nationally and responding to new and emergent needs of lesbian-feminists.

But over the past decade—building on the foundation created by folks like Pratt, Segrest, and South—North Carolina has continued to be an important site for the production of feminist and lesbian-feminist culture. Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s work as a cultural activist, particularly her publishing with Broken Beautiful Press and organizing through the Mobile Homecoming Project reconfigures and reworks visions of lesbian-feminism in a contemporary context. In 2011, Carolina Wren Press published Minnie Bruce Pratt’s poetry collection, Inside the Money Machine, featuring poems about working men and women facing contemporary challenges under aggressive commodity capitalism. Inside the Money Machine, Pratt’s fifth full-length collection, joined Shirlette Ammons’s debut collection, Matching Skin, published by Carolina Wren in 2008. Generational transformations continue to stoke the fires of lesbian-feminist print culture in North Carolina, connecting lesbians’ lives and livelihoods to poetry, art, and revolution.26

This article first appeared as “Night Heron Press and Lesbian Print Culture in North Carolina, 1976–1983” in the Summer 2015 Issue. Header image is taken from the inaugural issue of Feminary.

Julie R. Enszer is working on a book manuscript, A Fine Bind: Lesbian-Feminist Publishing from 1969 through 1989, that examines the cultural and political significance of lesbian-feminist print culture. Her scholarly work has appeared or is forthcoming in Frontiers, Journal of Lesbian Studies, WSQ, and Feminist Studies. Enszer is also the editor and publisher of Sinister Wisdom and curator of the Lesbian Poetry Archive, www.LesbianPoetryArchive.org.NOTES

- Harriet Desmoines and Catherine Nicholson, “Notes to a Magazine,” Sinister Wisdom, [July 1], 1976, 1; Ibid.

- For more about lesbian-feminist print culture, see Alisa Klinger, “Writing Civil Rights: The Political Aspirations of Lesbian Activist-Writers” in Inventing Lesbian Cultures in America, ed. Ellen Lewin (Boston: Beacon Press, 1996), Kate Adams, “Built Out of Books—Lesbian Energy and Feminist Ideology in Alternative Publishing,” Journal of Homosexuality 34, no. 3 (1998), and Trysh Travis, “The Women in Print Movement: History and Implications,” Book History 11 (2008): 275–300.

- Alice Echols’s history of radical feminism, Daring to Be Bad, frames the focus of the WLM as New York City, as do recent popular histories by journalist Gail Collins (When Everything Changed) and journalist and historian Ruth Rosen (The World Split Open). For works that document WLM histories outside of New York City, see Anne Valk’s Radical Sisters: Second-Wave Feminism and Black Liberation in Washington, DC (2008), Anne Enke’s Finding the Movement: Sexuality, Contested Space, and Feminist Activism (2007), Judith Ezekiel’s Feminism in the Heartland (2002), and Nancy Whittier’s Feminist Generations: The Persistence of the Radical Women’s Movement (1995). Katarina Keane’s dissertation, Second-Wave Feminism in the American South, 1965–1980 (University of Maryland, 2009), and La Shonda Mims’s dissertation, Lesbian History in Charlotte and Atlanta (University of Georgia, 2012); Jennifer L. Gilbert, “Feminary” of Durham-Chapel Hill: Building Community Through a Feminist Press (Master’s Thesis, Duke University, 1993); “1970s North Carolina Feminisms,” an online exhibition, accessed August 19, 2012, http://sites.duke.edu/docst110s_01_s2011_bec15/.

- Tamara M. Powell’s article, “Look What Happened Here: North Carolina’s Feminary Collective” (North Carolina Literary Review no. 9 [2000]: 95–98), provides an excellent history of Feminary; the same issue of the North Carolina Literary Review also contains Cherry Wynn’s “Hearing Me Into Speech: Lesbian Feminist Publishing in North Carolina,” which discusses Feminary and the careers of Minnie Bruce Pratt, Mab Segrest, and Dorothy Allison; Research Triangle Women’s Liberation published its first newsletter in 1969. In 1975, the newsletter was retitled A Feminary, after a concept in Monique Wittig’s Les Guérillères. In 1976, the energy behind the Feminary Collective waned and the journal became moribund. Two years later, at the Southeastern Gay and Lesbian Conference, Susan Ballinger, Mab Segrest, Minnie Bruce Pratt, and Cris South agreed to revitalize Femi-nary and turn it into a lesbian journal. Feminary thrived for five years between 1978 and 1983. Then a strong collective of lesbian-feminists, including Pratt, Segrest, South, Ballinger, Helen Langa, Deborah Giddens, and others, produced Feminary. Within the pages of Feminary, the collective articulated “contemporary southern lesbian feminist theory” (Powell, 91); For Hogan’s account of the history of Carolina Wren Press, see http://carolinawrenpress.org/about/supporters; Kathi Gallagher, “Lollipop Power,” in off our backs 12 (June 1982): 15, 17. Lollipop Power continued publishing through 1986, although the volume of sales decreased dramatically during the late 1970s and early 1980s. In 1986, Carolina Wren Press assumed the titles from Lollipop Power when the organization folded.

- The alternate spelling, womyn, was embraced by many lesbian-feminists to express a consciousness of women autonomous from men. The other womyn’s music distributor, Goldenrod, was founded in 1975.

- Facsimile copies of Sound and Living are housed online at the Lesbian Poetry Archive, www.LesbianPoetryArchive.org; Alicia Ostriker, Stealing the Language (Boston: Beacon Press, 1986), 10.

- Minnie Bruce Pratt, The Sound of One Fork (Durham, NC: Night Heron Press, 1981), 9.

- Ibid., 12.

- Ibid., 29; Ibid., 35; Ibid., 36; “The Woman-Identified Woman” by Radicalesbians was initially published and circulated by women in New York in 1970. Know, Inc. of Pittsburgh, PA published it as a small pamphlet in 1970. The full text of “The Woman-Identified Woman” is available online at http://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/wlmpc_wlmms01011/; Adrienne Rich, “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence,” Signs 5 (Summer 1980): 631–60; Elly Bulkin, Minnie Bruce Pratt, and Barbara Smith, Yours In Struggle: Three Feminist Perspectives on Anti-Semitism and Racism (Brooklyn, NY: Long Haul Press, 1984).

- Mab Segrest, “I Live in a House,” in Living in a House I Do Not Own (Durham, NC: Night Heron Press), unpaginated.

- Segrest, Living, 11.

- Ibid., 2.

- “Grant application,” folder “Fund for Southern Communities application for Night Heron Press, 1982–1983, Box 36, Minnie Bruce Pratt Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.

- Ibid.; Ibid. The third book was never published. Saralyn Chesnut and Amanda C. Gable, [End Page 55] “‘Women Ran It’: Charis Books and More and Atlanta’s Lesbian-feminist Community 1971–1981,” in Carryin’ on in the Lesbian and Gay South (New York: New York University Press, 1997); “July 9, 1981 letter to Elizabeth Knowlton,” folder “Knowlton, Elizabeth, 1979–1994,” Box 55, Minnie Bruce Pratt Papers, Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University; Minnie Bruce Pratt moved to the Washington, DC area in 1983; she continued to write and publish poetry, notably winning The Lamont Prize in 1989 for her second collection, Crime Against Nature (Ithaca, NY: Firebrand Books, 1990). Mab Segrest worked with North Carolinians Against Racist and Religious Violence from 1983 until 1990; her book Memoir of a Race Traitor (Boston: South End Press, 1994) documents this experience.

- Letter to Elizabeth Knowlton, folder “Knowlton, Elizabeth, 1979–1994,” Box 55, Minnie Bruce Pratt Papers, Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University; Ibid; Ibid.

- Ibid.; Ibid.

- Ibid.; August 10, 1981, letter to Ben Weaver, folder “1981 (1 of 2),” Box 61, Minnie Bruce Pratt Papers, Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.

- January 20, 1986, letter to Sheila, Folder, “1986–1988 2 of 2,” Box 62, Minnie Bruce Pratt Papers. Correspondence between Pratt and South indicates that South produced at least 500 copies as a way to pay off a debt that she owed Pratt (Folders 1–5 “South, Cris, 1978–1979, 1982–1986,” Box 57 & 58, Minnie Bruce Pratt Papers, Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University); Sound sold for $2.00. I estimate that 1,800 copies sold with total revenue of $3,600 and net revenue of $1,200 (September 15, 1982, letter to Nancy Bereano of The Crossing Press, folder “Correspondence 1981–1985 2 of 4,” Box 12, Minnie Bruce Pratt Papers, Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University); Folder “Correspondence 1981–1985 2 of 4,” Box 12, Minnie Bruce Pratt Papers, Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.

- Joy Parks, “The Southern Column,” in Body Politic 97 (October 1983): 36.

- Jewell L. Gomez, “Review of The Sound of One Fork,” in Conditions: Nine (1983): 173–75; “To Our Readers,” Conditions: Nine (1983): 1.

- Segrest’s later collection, Memoir of a Race Traitor, explores her work against racist and religious violence, two themes that are important to both Segrest and Pratt at the time the chapbooks are published, but are muted in their treatments in the collections of poems.

- Cris South, Clenched Fists, Burning Crosses: A Novel of Resistance (Trumansburg, NY: The Crossing Press, 1984).

- Beth Hodges described print as the “medium of our movement” in her address to the Lesbian Writers Conference in Chicago on September 17, 1976; Jan Clausen uses the phrase in her chapbook, “A Movement of Poets” (Brooklyn, NY: Long Haul Press, 1981). Critics Katie King, T.V. Reed, and Kim Whitehead also discuss this idea in their work.

- “Running this old printing press,” folder “Cris South 1978–1979, 1982–1986,” Box 57, Minnie Bruce Pratt Papers, Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University. At the bottom of the page, South typed, “Dedicated to Minnie Bruce” and then in handwritten text wrote, “I love you! Chuckle—Cris.”Mab Segrest, Memoir of a Race Traitor (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1994).

- Mab Segrest, Memoir of a Race Traitor (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1994).

- For more on Gumbs, see http://alexispauline.com/.