“‘I would say the average age of most people that buy spot now is probably sixty. Nobody young comes in this door and buys a box of fish.'”

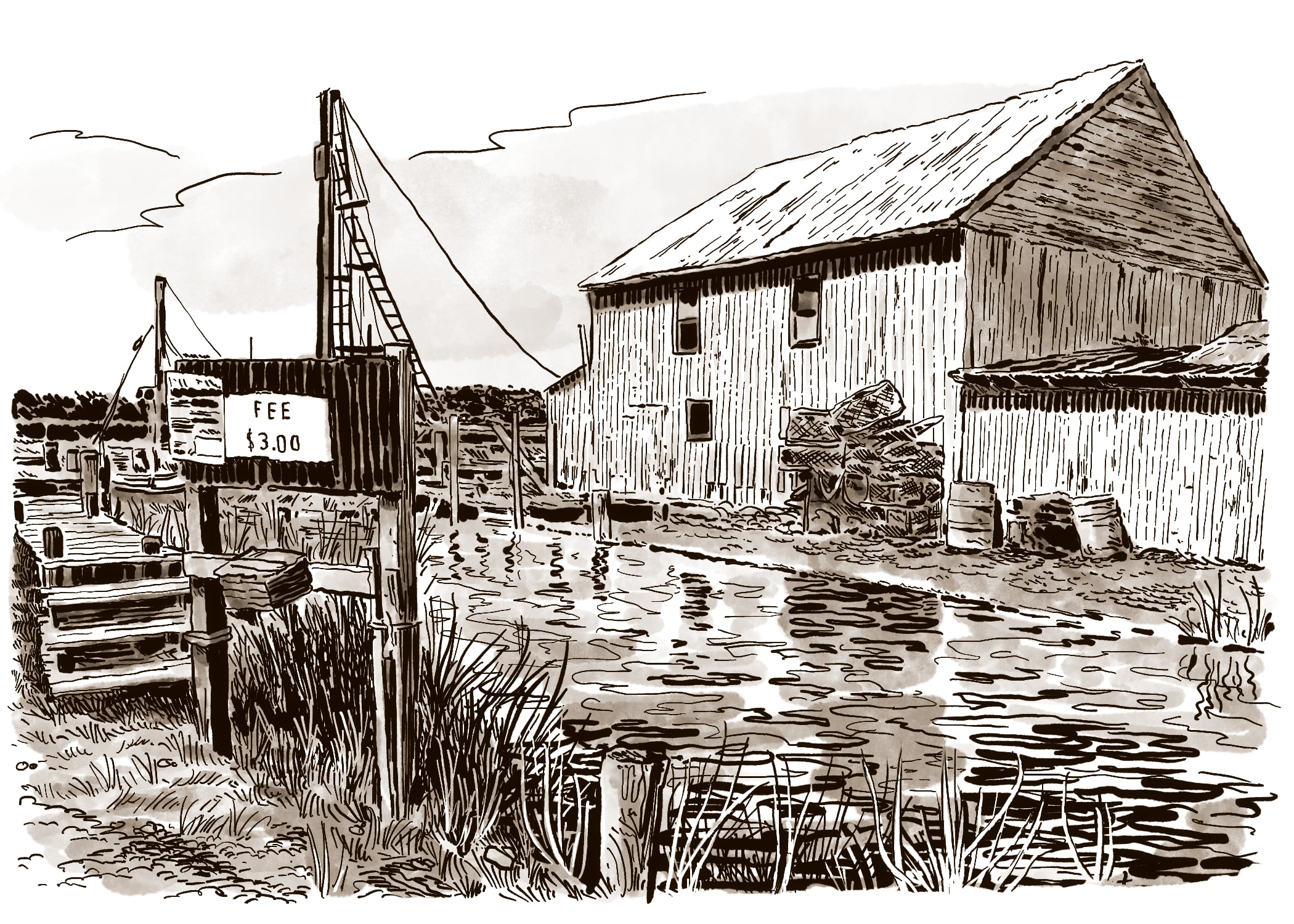

Late summer the phone rings in the Bayford Oyster House on the Eastern Shore of Virginia. “Bayford,” H. M. Arnold answers. “Yes ma’am,” he says a few seconds into the conversation, “I don’t have any spot today. They don’t seem to be running. Nobody I know has them. I have some hardheads though, if you want to drive down and get them. Thank you.” H. M. shakes his head and sits down in his plastic chair by the stainless steel counter where he shucks oysters for the winter trade from Thanksgiving to New Years. The afternoon steams August hot, a bit of breeze ruffles the water on Nassawadox Creek outside the door. The tide is rising and soon enough will seep under the sills and into the dock end of the venerable shucking house, sheeting over the old concrete floors, compelling H. M. and his visitors first to walk on boards and then to slosh their way past the soft-shell crab shedding tanks now all but closed down for the season. Tank, the monumental Chesapeake Bay retriever who lives up the hill, stands in the boat launch with a chunk of pine branch clenched in his jaws, waiting for someone—anyone will do—to seize the wood and pitch it into the water. Strangers shy away from the massive dog; regulars ignore him. Tank perseveres. And so do the callers seeking spot, a panfish deeply savored in this corner of the world. The phone rings. “Bayford,” H. M. answers.

Spot, it seems, have diminished in their numbers since 1890, when a fish census noted: “Large numbers of young spot from 3 to 4 inches in length were seined in the bay at Cape Charles City. They were present in abundance, numerous schools being seen … As a pan fish, the spot is the most highly prized of all fishes sold in the Norfolk market.”1 Writing from North Carolina, Hugh M. Smith reported in 1907, “The spot, which gets its name from the round mark on its shoulder, inhabits the east coast of the United States from Massachusetts to Texas, and is one of the most abundant and best known of our food fishes.” Smith concludes, “The spot ranks high as a food and is by many persons regarded as the best of the pan fishes. There is a good demand for North Carolina spots in Baltimore, Washington, and other markets of the Chesapeake region, and the fish is also rated high as a salt fish for local consumption.”2 Spot, another observer reported, “are the smallest members of the croaker family that are sold with any regularity. Most specimens weigh only about ¼ pound. Spots are easy to recognize by their spot right behind the gill opening.”3 The spot’s distinguishing markings, Pooh Johnson, oysterman and cook in Onancock, Virginia, asserts are the marks of Christ’s fingertips imprinted when He divided the loaves and fishes for the multitude in Mark 6:41.4 Communion of a different variety causes H. M.’s phone to ring.

Uncommonly common in the lower Chesapeake and in North Carolina’s sounds, the spot (also known regionally as Jimmy, chub, roach, Goddy, and Lafayette) lives inshore from late spring through autumn and winters in deeper offshore waters during the cold months: “The waters of the Chesapeake Bay off Norfolk, Virginia, are such prime spot fishing grounds that out-of-town menus often list this small, sweet fish as ‘Norfolk Spot’ … Prior to spawning season in the fall, the spot takes on a golden color much like its cousin the croaker. At that time the fish are often referred to as ‘Ocean View Yellow Bellies’ because they congregate to feed off Ocean View, a Norfolk neighborhood on the Chesapeake Bay.”5 When spot run, H. M.’s phone rings with unmistakable urgency.

Fresh or Fried: A Southern Cultures Seafood Reader

Twelve fish(ish) tales from the archives (with accompaniments). Read the whole platter here.

The spot’s culinary associations are tightly knit into the history of place, but over time its connections with class have become more generous. A late 1880s survey of the diets of African American families in the Virginia Tidewater recorded spot (identified as roach) along with other fish including croaker (or hardhead), and salt or smoked herring. Along with sturgeon heads (used for fish chowders) and snapping turtles (also cooked in stews or soups), the spot lacked an august historical pedigree. Danny Doughty, whose family ran a fish store on the highway near the railroad town of Painter, spoke to the close associations the fish held with the less affluent community: “Spot was one of the staple fish, one of the cheaper fish.” When it came to eating spot, waste was a sin: “If you were a real fish eater, you knew how to get to all the good meat, and just leave the bones. It was kind of frowned upon if you were to fillet or waste any of the fish, if you didn’t eat every bit of it and didn’t clean it to its full potential to get the most out of it.”6

Charles Amory of Amory’s fish wholesaler across the Chesapeake Bay in Hampton, remembered one of the few instances in which spot successfully climbed the social ladder. A Washington, D.C. fishmonger, he recollected, “called me one day and he said, ‘I’ve got a special order. I need to … go to the White House.’ He said, ‘I want you to handpick them, mark the box so I know which one it is.’ And we did it, and sent them up there … That was the only high-dollar, white tablecloth that I knew directly about. And, you know, years ago, I’d send spot over to the yacht club, and they’d cook them for lunch. We didn’t usually send very many because there weren’t that many of us that would eat them. We didn’t even try that this year. The cooks that graduated from the culinary institute in Norfolk didn’t know how to cook them.”7 Over a century later, the spot plays a leading role in a culinary social imaginary centered on nostalgia and authenticity.

Commentaries on spot tend to be notably incisive. “The spot,” one source notes, “is generally similar in appearance to the Atlantic croaker, but the body is shorter and deeper and there are no barbels on its lower jaw,” concluding, “there is no commercial fishery for this species, but considerable quantities are utilized as panfish by sport fishermen.”8 “Spot,” another writer observed with equal concision, achieves a “maximum length about 35 cm; common length 15 to 25 cm. This fish is blue-grey above, with golden gleams, and silvery below. Its range is from Texas to Cape Cod. It frequents sheltered bays and estuaries and is of some commercial importance in the Chesapeake Bay area. Cuisine: A good pan fish.”9 And with greatest rapture, a spot fan succinctly enthused, “Though small, rarely over a pound in size, the spot is considered the best pan fish around. Many Tidewater Virginians salt the tiny fillets down in crocks for later eating during the winter months. Nothing, however, quite beats a spot fresh from the water and into the pan. Rolled in cornmeal and quickly fried in hot fat is the traditional way of cooking them.”10

Panfish, something of a dismissive term, is defined as “fish suitable for frying whole in a pan, especially one caught by an angler rather than bought.”11 Still, pan-fish could be purchased in seafood markets throughout the South, for example at Young’s Fish Market, far from the Atlantic Coast in the mountain town of Asheville, North Carolina, where the proprietors advertised in 1900: “For Frying [-] Smelts, Small Trout, Croakers, Perch, and Panfish.”12 The designation, linked to the “amateur” fisherman, carries connotations of a “simple” preparation lacking the status of a recipe and outside the scope of a cuisine. P. G. Ross of the Virginia Institute for Marine Science and a decoy carver, after inspecting a stretch of oyster ground, leaned over the back of his truck and recalled fishing for spot as a boy. It was the one fish he could count on catching. Carrying spot home to his grandmother made him feel as if he were contributing to the family larder in a meaningful way.

On the Eastern Shore of Virginia, “panfish” simply refers to a host of small fish that include spot, croaker, sand mullet, jumping mullet, hogfish, swelling toads, and more. The idea of the panfish relies on four characteristics: size (they fit whole into a skillet), status (they tend to be associated with less desirable fish—often linked to qualities of oiliness or boniness), procurement (although netted, seined, or trapped commercially, panfish are commonly associated with amateur angling), and preparation (largely fried). In essence, panfish, spot in particular, are notable for their everydayness, remarkable only in the moments of their absence. When folks call H. M. Arnold for spot, it’s about layers of memory and longing that transcend the culinary specifics of the fish they eat. Spot are an acquired taste, a learned delicacy about place and identity.

When it comes to spot, nobody knows the history of the market like father and son Charlie and Meade Amory. Meade, who runs the family fish and trucking company, sits between “a hundred years of experience” with his father Charlie on one side and general manager Richard Coughenour on the other. A single shared desk runs the length of the room, fronting a picture window that looks out onto the loading docks where workers navigate small forklifts, rocketing around pallets of seafood, loading orders into refrigerated trucks destined for the Midwest. The open-timber framed structure smells of brine, fresh fish, and the chill of refrigeration. In the distance the warehouse ends at the water where fishing boats dock and deckhands offload their catch. Amory’s workers, well gloved, work through the fish piled on sorting tables, distributing them quickly onto beds of crushed ice packed in waxed cartons. The fish arrive clear-eyed, pink-gilled, and scented only with seawater. They are so fresh that Meade boasts, “They’re still kicking.” Iced, a portion of the haul goes directly onto the waiting trucks and to market; the remainder are hauled across the wet concrete floors and into a walk-in freezer where they await demand.

Amory’s Seafood is the last business of its kind along a waterfront increasingly confronted with urban renewal schemes, new houses, condominiums, and acres of recreational boats. Only Cooper’s, the equally venerable marine supply store on the opposite side of King Street, keeps it company, remembering the vitality of the seafood trade when a remarkable variety of fish were readily available, including a number of species long out of gustatory favor. Spot, according to Meade Amory, who surveys the packing room bustle, have always been a seasonal staple:

Spot run out of the bay in the fall, and that’s the big run of fish, and that’s when everybody catches them in gillnets, haul seines, pound nets, for the most part … People will set up anywhere along the shore with gillnets, mostly. It can start as early as the middle of August or as late as the first or second week of October, and when it starts, it usually lasts for anywhere from four to six weeks. Sometimes it can last as long as eight weeks. The fish leave the Bay, and that’s when you catch them … They get ready to run, something signals them—Mother Nature—usually a good north wind gets them moving … The fish are white all summer, and then, when they go to start running, they are gold—shiny, pretty gold. Gold belly, the fins are bright, shiny gold, and the customers know that’s what they’re looking for and that’s what they’re asking for. They used to call them Norfolk Spot, and I don’t know if it has to do with when they leave the Chesapeake Bay, as they go around Cape Henry and come through Ocean View area and out and down the beach—that’s when they’re the prettiest color.

Meade Amory continues as his father listens: “There’s a very small market for spot. It’s pretty much just east coast, and pretty much just the middle states. We do send some to Boston, and some to Miami, but mostly New York to Atlanta, and, probably, I’d say 60 or 70 [percent] of it is Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina.” The spot once landed were tallied by weight and number and boxed for shipping: “Everything used to be weighed in wooden fish boxes, and they were 100 pounds. One hundred pounds of fish; put ice in the bottom and ice on top—that’s 100 pounds. When you hear people talk about a count, particularly with spot or croaker, they talk about a head count to the hundred pound. A 200-count spot is a half a pound spot.”

An autumn-like blue-sky July early morning, the sun lighting up the quiet surface of Nassawadox Creek, H. M. in oilskins and I in a heavy rubber apron push off from the Bayford Oyster House dock in search of spot. His dog Mick curled in the bow dreams to the rhythmic slap of water and the outboard’s grrr. We skim past lines of crab pots, deep green marsh, and staked clam and oyster grounds where growers are already at work culling their crop, heading toward the deep hole where H. M. set his nets in pre-dawn darkness. A black flag fashioned from a ruined plastic trash bag flutters above the cork that marks one end of the hundred fathom net. A red float marks its terminus in the distance. H. M. idles the motor, sets out two baskets for sorting the fish, and deftly hooks the marker, hauling it into the boat. “You pull the cork line, Cap’n,” he says to me, and I jump to. Hand-over-hand, we haul the net. The fish are scarce, but they are here. “Bluefish,” H. M. remarks, slipping one from the mesh and dropping it into the orange basket. “Croaker,” flipping the grunting fish into the blue basket. More croakers. More blues. We encounter a handful of menhaden: “Carolina spot,” H. M. smiles at the insult, tossing the fish back into the creek. More croakers and bluefish—and then we begin to pull in a few spot. They are beginning to show some size after a summer of foraging the creeks and bay; a couple show the first golden tones of the fall run on their underbellies. We’re done. Two hauls of the net yield fifty pounds of croakers, maybe two-dozen bluefish, a sea trout, and perhaps a dozen spot. “It’s not like it was,” H. M. observes as he revs the engine and we head back to the dock.

Casual fishermen go after spot with rod and reel outfitted with a bottom rig baited with bloodworms. Inshore commercial fishermen, on the other hand, generally pursue three approaches: haul seines, gill nets, and traps or pound nets. Haul seines consist of large nets run out from shore and then circled back to capture fish running parallel to the shoreline. Haul seines are rare now, but in the 1950s and ‘60s news of a seine traveled in the community and folks turned out with burlap bags to retrieve the by-catch when the fishermen’s labors were done. The dark rolls of the snake-like net lay on the silver bright sand of a moonlit beach, the doomed fish gasped wrapped in its folds, the bystanders gleaned its length. Pound nets consist of a line of heavy wooden stakes planted at right angles to shore that extend into a pen-like enclosure. Nets are hung from the poles in a configuration that leads the fish into the pen and a trap known as the heart. The fish migrating along the shoreline hit the net and follow it out to get around the barrier only to find themselves entrapped in the heart. Gill nets are run laid out with the tides and marked at either end with a buoy. Following the turn of the tide, the fisherman hauls the net onboard, wresting the fish out of its mesh and into the baskets.

H. M. Arnold reprised gill netting for spot on the Eastern Shore: “The boys that really gill netted years ago, they would at the end of the season, like [the] end of August, if they knew a northeaster was coming, they would grab their gear and go to the Western Shore and anchor their nets out because northeast [winds] blew them up against the shore over there. And, they’d have big catches … And they’d catch them in fish traps over there, too. I mean, by the tons. Over here [on the Eastern Shore], you don’t.” He continued, noting that spot tend to segregate themselves from another favored panfish, the croaker. “When they mingled, though,” he began, “you’d go to one net, and it would be nothing but croakers, and you could have a net by that barge [nearby], and it would be nothing but spot. And that’s what I wanted—spot. You can have them croakers.” He laughs and then recalls how another Bayford waterman needed help on one memorable occasion: “[O]ne day, I had fished and come in. I mean, everyone was catching them. I had probably 1500, 2000 pounds. Of course, they were fishing a lot more nets. And I came in, went up to Ches-Atlantic [a seafood wholesaler in the railroad town of Painter and now closed] and unloaded and brought my ice back and everything.” Steve Bunce, H. M. smiles,

was on VHF [radio] and we’re sitting in the store, and he called, and goes, “What’re you doing?” “Nothing.” And he said, “Man, I got so many fish, can you come out here and take one?” And, I mean, just out here. Not two miles off … And I said, “Well, we got a couple of them in here. We’ll come out and take one.” So, we went on out, and I pull up to him. And he had a load of croaker or spot in that one. I think it was croakers. I said, “Which one you want me to take?” And he goes, “Well, I got two of them. There’s one here and one there.” I said, “OK, I’ll take that one.” So, we’re getting ready—we’re getting our oilskins on and everything—and we pull that net. It had all spot in it. He got through that one and went to the next one, and it had all croakers in it again. In about three hours we were done, man. We probably had about 1500 pounds in that net. It was a load!

Spot, H. M. explains, could also be netted through a technique known as “sounding” that fished the space between offshore sandbars and the shoreline: “Inside the shoreline there used to be two or three sloughs. They were about four foot deep. And we’d go out there on the flood tide, just take one net—about fifty fathoms, three inch, three-and-a-quarter [mesh] back then because they were nice spot—and run the net out. Of course, we didn’t have a big boat then. A little old scow was all we had. And we’d go around the net, maybe ten yards from the net, and as we did it, we’d take a pole—and it was hard sand, and there was some grass out there then, too. Ain’t too much grass out there now. [We’d] go around that baby two or three times, fish the net, and you’d have yourself a basket of nice spot. And you’d run it back again, or if you didn’t even take it up [and] you just ran it over the boat, you could do that most of the flood tide … Just run the motor and the boat and somebody would be up front there hitting it, sounding it with a pole unless you were by yourself, then you did it. Go around it maybe two or three times. I’ve tried it two or three times, but it hasn’t worked like it used to. We’d catch two or three hundred pounds of them.”13

The taste for spot is linked to time and place, as H. M. muses, “the old generation is gone,” adding the current market wants “round or square fish.” “It used to be,” he concludes, “I could make a living selling them here and not even going to Ches-Atlantic.” The home consumer market, Meade Amory agrees, has aged, “I would say the average age of most people that buy spot now is probably sixty. Nobody young comes in this door and buys a box of fish. We don’t sell retail, we sell wholesale, so it would only be a fifty-pound box as the smallest amount, generally, other than maybe frozen twenty-five-pound boxes of spot. People don’t come in and buy that anymore. The older people—fifty, sixty-year-old people—still do, but no young people.” Meade Amory adds, “There are a few grocery chains that still carry them. I don’t think you’ll see them at your high-end chains. It’s the old-timers. People come in here and buy fifty pounds at a time in the fall when they know. They’ll buy them and take them and split them up with their neighbors and salt them or have a fish fry for their church or that sort of thing. A lot of people used to salt them. That was before freezing. We still do a little bit, because it’s tradition and we’re used to having a breakfast like that. My grandmother used to make it, a breakfast for my dad and uncle and I.” Besides spot, Eastern Shore folk also salted croaker, mullet, and blue fish.

According to the Amorys, there is only one way to cook salted spot. Meade spoke for the family, “My whole life I only had it one way, and that was the way my grandmother cooked it.” He explains, “You take them out of the water the afternoon before you’re going to cook them and you soak them in fresh water, let some of that salt come out of them. You can rinse them off before you go to bed and put fresh water in them, and then rinse them off again. Put them in a pot of water and boil them. Fry some bacon. When you take the spot out of the water, lay them in a platter with just a little bit of the juice from the pot, and then pour your warm bacon drippings over the top of them. It’s a lot of sodium and a lot of bacon fat; it’s a miracle we’re still here talking about it.” Tom Walker, whose family has run a clam and oyster business in Willis Wharf since 1889, declares the spot the tastiest of the inshore fish, noting that they are bony, possess a strong, rich flavor, and are “a little irregular.” In quest of a more healthful outcome, he cooks them on the grill: “I’m still trying to find a way to keep the damn things from sticking on the grill … you have to start them on a cold grill and bring the heat up.” Salting the fish, he adds, helps keep the skin from coming off. When the spot is done and the side pricked with a fork, clear oil from the fish runs out. Still, he acknowledges that there is work to be done on refining his technique.14

H. M. Arnold speaks with authority, “The only way to cook a spot is fry them.” Danny Doughty, seconds this point of view, remembering how African American women would have their purchase scaled, gutted, and cleaned before frying:

We would prepare them, clean them in the fish market, like, everywhere you could think of. And, most of the black culture there would have them cleaned—the older women especially—with the head left on and split down the back, which you took a sous knife … And, you would cut right down the back of the head after you scale it, and slice all the way through the head, the eyes, and everything, the gills all the way down the backbone to the tail. Then, you’d open it up, just like butterflied it wide open. And then we’d take the knife and scrape from the inside of the head—leaving the eyes in because they loved to eat the eyes—scrape the gills, and then all the insides out of them. Once that was done, then you’d rinse some off, and usually for the most part they would fry them in lard, most of them in a cast iron frying pan at a really high temperature, and they were really, really good.15

Although spot can be cleaned by gutting the belly, most Eastern Shore diners prefer their fish split down the back—and more often than not with the head and tail left attached. Tracey Rasmussen cleans spot to order in her seafood shop by the highway in Keller, Virginia. She scales the fish and then, pressing the fish with her palm against the cutting board and wielding a flexible fillet knife, she makes an incision along the top of the dorsal fin. Gently working the point of the blade into the body, she delicately rides its edge along the curvature of the rib cage, being careful not to pierce the abdomen. With the cut complete, she stands the fish upright and brings the steel down through the skull neatly bisecting the fish the entirety of its length. She completes the operation, laying the spot open, extracting its viscera, and cleaning out the black body fat (the last step being anathema to some old-school gourmands). H. M. dresses his spot in the same manner but with the head off. Both techniques produce a fish that can be laid flat in a pan of sizzling oil and fried to order.

As far as size and flavor go, H. M. notes: “A pound is big … Really, when he gets that big, he’s not as good as a twelve or fourteen-ouncer. Kind of gets a little stronger … The thing with them is, if you really cook them right, you eat this side of them and all you have to do is pull the backbone out—and there’s no bones anywhere else, so it’s like pulling them all out—and then you eat the other side. That’s how we always did it. Of course, most of them like the tail fried crispy. They like that.” He adds, “When people cook a big spot, they strike him about three times with a knife on each side, so he can go ahead and cook quicker.”

Danny, who also operated a restaurant associated with the family fish store, expanded on the basic preparation: “We would just wash them off, salt and pepper, and usually use pancake flour because … pancake flour has a little more sugar content in it. It makes it brown a lot more even and quicker. Because fish doesn’t take that long to cook at a higher temperature, quicker time, that’s the way you cook good fish. It sears the outside of them.” He notes, “we use a lot of cast iron, especially if we’re doing … a reunion or something. Then we get a fifty pound box of spot, or a bushel basket of spot or whatever, and clean them all and put them in—wash them off and clean them in some salt water, and then salt and pepper and a little bit of flour, pancake—or mix the two together was a good way to do it because you get a little bit of the sweetness of the pancake flour and then the regular flour mixed in with it.”

When you get right down to the nub of the matter, though, people fry spot, and frying spot (or any other fish) is so elemental that it receives scant mention. Bessie Gunter, whose Housekeeper’s Companion is the first published Eastern Shore of Virginia cookbook, wrote only: “To Fry Fish. Have a hot pan and some boiling lard in it or the drippings of fat meat (equally good). After the fish have been properly prepared, dredge them in flour and put them in the pan to fry.”16 Within those simple instructions resides a universe of variation and personal preference. The greatest distinctions are between spot fried hard or soft and spot fried head on or head off.

Danny Doughty, like many others, savored spot fried hard and head on: “Fried hard, yeah, that’s the way cause they were so crisp on the outside, and then … it would steam the inside. [S]pot has got a real kind of sweet, nice, moist consistency. It isn’t dry fish. And the fat in it would just really go through the meat. You wanted to get them in a hot temperature and back out. [E]arly on in my life, [we] fried everything in lard and then Crisco. Then using a cast iron frying pan, you get a hot temperature and roll them in there. You usually cook seventy-five percent on one side, flip it, the other side the other twenty-five percent, flip it out, it’s done.” Mary Onley, artist and minister, described much the same practice, comparing the spot to its cousin the croaker or hardhead: “They taste better to me than croakers. But they have a little bit more bones, little small bones in it. But they’re good. And so what I do, I make me a batter … and in my batter I don’t put nothing but salt and pepper and flour, and I put them in plenty of hot grease and let them fry, and I get them after a good ten minutes in that hot grease and … eat it. I fry them hard. I love them hard. I love to hear the crunch in them.”17

Danny Doughty rhapsodized that the delectability of spot fried hard lay in total consumption: “Oh my gosh, it was so good … I can just see it now, taste it now. Like, when they were crisp, just chomping the tail right off, eating the tail, every bit of it, all the fins, the eyeballs, the gills—even though we didn’t eat the part that we throw away, the outer sides of the gills. There was nothing thrown away but the actual bone that run through the core of the fish and the outer bones that come off from it. Everything was eaten. That was one of the beauty parts of it being real fried hard, because you could eat everything.”

When Addie Sue Smith of Exmore says that she savors her spot “fried soft,” and adds, “there’s a certain taste in that head if you want to go in and fool around with it,” she reveals discernment.18 Danny Doughty spoke to the positive qualities of spot fried soft, “It was a thing—and if you had children in a family, they’d say, ‘Cook one of them soft,’ ‘I’m going to fix the baby some fish,’ or whatever. So, they would kind of pull the skin off real easy, and then kind of slide the meat off the bone onto a little plate to itself so they wouldn’t get choked on a bone.” Spot fried soft, he noted, also appealed to “some of the older folks, if they didn’t have teeth or if their teeth weren’t very good. They’d say ‘Fry them soft! I don’t want them hard. They’re too hard on my gums, my teeth!’ You know, it was kind of funny, but it was so true. I mean, they were telling the truth. Their teeth weren’t good, and they didn’t want to be crunching on spot.”

Fairy Mapp White, author of the Foolproof Cookbook (1958), which was often presented to Eastern Shore brides as a trousseau gift, offers little direct commentary on the spot, simply grouping it with other local fish, but she did introduce the importance of side dishes. After frying the fish in bacon fat, she garnished them with “strips of fried out bacon or salt pork” and then instructed the cook, “Serve at once on hot plates with meal cakes, cornbread, or hot rolls, with plenty of good coffee.”19 Danny Doughty, who always speaks lovingly of spot, associates it with favorite sides: “Fried apples—they were unbelievable!” He then described their preparation: “Cut up, leave some of the peeling on, take the core out, and tons of sugar and butter, and fry them in cast iron frying pan on top of the stove until they cook down into almost an applesauce consistency, a little bit of the body of the apple left, but just a little bit of tart and sweet and kind of a golden brown. I mean, that combination of that little bit of saltiness of the spot and you slip a little bit of the apple on that and then take a bite. That salty sweet mixture, mmm, that was really unbelievable.” “Also, sweet potato, great with it, too,” he enthused, “Then, of course, you had to have fried white potatoes. Either fried white potatoes usually with onions, you know, peeled, of course, a little salt and pepper, little bit of Crisco fried up, and that was a staple. You lived off of potatoes quite a bit. Then to have the spot and the apple and the potato together was the real deal, you know … we had fried sweet potato too, which was just a sweet potato sliced in slices about a quarter inch thick, and just fried in a frying pan with a little bit of oil or shortening, and then sprinkle a little bit of sugar over top of them.” Other diners cited greens, stewed tomatoes, and spoon bread as favored sides for spot.

Whatever side dishes may have been preferred, Danny Doughty distilled the essence of the experience: “Spot is that old school staple food that was cheap, good, available, and it was just a great tasting fish. People enjoyed the art of eating fish, which is not conducive [to] today’s culture. To see some of the older people do it, it was like—you learn from them how to pick and separate and be able to lift a part up just right and then a hint of the apple, a little bit of potato, whatever. It was just really more like a little symphony you’re kind of playing with over the plate.” Danny stopped, a thoughtful, wistful hungry look in his eyes.

Bernard L. Herman is the George B. Tindall Distinguished Professor of American Studies and Folklore at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His books include Thornton Dial: Thoughts on Paper (2011), Town House: Architecture and Material Life in the Early American City, 1780–1830 (2005), and The Stolen House (1992). He has published essays, lectured, and offered courses on visual and material culture, architectural history, self-taught and vernacular art, foodways, culture-based economic development, and seventeenth and eighteenth-century material life.

1. Barton A. Bean, “Fishes Collected by William P. Seal in Chesapeake Bay, At Cape Charles City, Virginia, September 16 to October 3, 1890,” Proceedings of the National Museum, XIV (1891), 89.

2. Hugh M. Smith, The Fishes of North Carolina, in Joseph Hyde Pratt, ed., North Carolina Geological and Economic Survey, vol. II (Raleigh: E.M. Uzzell & Co., 1907), 316–317.

3. James Peterson, Fish & Shellfish (New York: William Morrow, 1996), 351.

4. Pooh Johnson interview with Bernard L. Herman, December 16, 2012; http://www.kingjamesbibleonline.org/Mark-6-41/.

5. Mary Reid Barrow with Robyn Browder, “Spot: Norfolk, Virginia’s Claim to Piscatorial Fame,” The Great Taste of Virginia Seafood: A Cookbook and Guide to Virginia Waters (Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing, 1984), 84.

6. H. B. Frissell and Isabel Bevier, Dietary Studies of Negroes in Eastern Virginia in 1897 and 1898, Bulletin No. 71, U.S. Department of Agriculture (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1899), 11.

7. Charles and Meade Amory interview with Bernard L. Herman, December 28, 2011.

8. A. J. McCalne, The Encyclopedia of Fish Cookery (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1977), 124. Extended discussion of family Sciaenidae and the spot in context of the drum, 121–125: “They occur chiefly on the Continental Shelf, often over shallow sandy bottoms near estuaries and in the surf. Drums are so named because of their specialized ‘drumming muscle’ which by rapid and repeated contraction against the gas bladder, produces a distinctive sound that can be heard on land. Among some the smaller sciaenids this is more of a grunting or croaking sound, hence the common name distinction between drums and croakers” (121). Other Chesapeake sciaenids include Atlantic croaker, banded drum, black drum, kingfish, red drum, and silver perch—all fished commercially and recreationally. Note as well that otoliths (ear bones) are common to this family and that they are used to determine age, always a detrimental inquiry for the fish.

9. Alan Davidson, North Atlantic Seafood (New York: Viking Press, 1979), 112.

10. Mary Reid Barrow with Robyn Browder, “Spot: Norfolk, Virginia’s Claim to Piscatorial Fame,” The Great Taste of Virginia Seafood: A Cookbook and Guide to Virginia Waters (Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing, 1984), 84.

11. Google search result for “what is a panfish?” (July 9, 2014). Google ngrams charting the usage of the term reveal that it did not gain general circulation until after World War II, spiking in the 1980s. See Google Books.

12. Asheville Daily Gazette, Sunday, April 1, 1900, 8. www.newspapers.com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/image/58451905/terms=panfish.

13. H. M. Arnold interview with Bernard L. Herman, Bayford, Virginia, July 30, 2014.

14. Tom Walker, personal communication to Bernard L. Herman, March 8, 2012. See also, http://www.jcwalkerbrosclams.com.

15. Danny Doughty interview with Bernard L. Herman, February 18, 2013., Elizabeth A. Thompson transcriber.

16. Bessie Gunter, Housekeeper’s Companion (New York: John B. Alden, 1889), 47.

17. Mary Onley interview with Bernard L. Herman, Fearrington Folk Art Show, North Carolina, February 18, 2012.

18. Addie Sue Smith conversation with Bernard L. Herman, Exmore, Virginia, December 16, 2011.

19. Fairy Mapp White, Foolproof Cook Book (Baltimore: Monumental Press, 1958), 183–184. White’s cookbook updated and expanded Bessie E. Ginter’s work of the 1880s, a collection compiled from local cooks and a larger regional network of family and friends.