A stumppocked scene of profound and peaceful desolation, unplowed, untilled, gutting slowly into red and choked ravines. —William Faulkner, Light in August, 1932

In late spring 2016, Louisiana artist Monique Verdin arrived in the Netherlands for the annual shareholders’ meeting of Royal Dutch Shell armed with an impassioned message and a collection of her black-and-white photographs. The images, displayed as individual large-scale banners, revealed petrochemical plants looming over the wasted landscape, seasonal floods inundating impoverished neighborhoods, and denuded trees suffering the effects of toxic soils. A descendant of the indigenous United Houma Nation, Verdin had captured the scenes over a twenty-year period while documenting the oil and gas industry’s ruinous impact on her ancestral homeland in southeast Louisiana. The contamination of the state’s coastal waters and dredging of the fragile wetlands, she discovered, had left the tribal communities living along the Gulf of Mexico particularly vulnerable. With the rapid erosion of barrier marshes and encroachment of oil-slicked water upon homes, schools, and businesses, residents—including the artist herself—now confront the possibility of forced relocation and a dissolution of their way of life. Verdin’s graphic images may ultimately come to offer the last material evidence of the land’s existence.1

Yet her work is not without precedent. Southern artists nearly a century earlier faced their own ecological crisis, which they recorded on paper and canvas. Their images told of similar environmental degradation resulting from exploitation of the region’s natural resources, but by way of staple agriculture rather than fossil fuels. The eco-commentaries of these New Deal–era compositions have largely been overlooked; indeed, the artists themselves rarely articulated the societal impact of the scenes they observed. Contemporary viewers should nonetheless see in these landscapes an early failure of stewardship facilitated by lax governmental regulation, cheap labor, and poverty—conditions many southerners have continued to accept, if not encourage. While conservation initiatives implemented by federal agencies during the 1930s eventually ameliorated the land’s woes, these period works endure as a cautionary tale of environmental disregard and, anticipating the new millennial visual commentaries of Verdin and other artists, raise questions about the region’s longstanding fealty to extraction economies. The survey that follows demonstrates that the South has repeatedly conceded to the plunder of its resources, a tragic pattern that arguably lies at the heart of its identity.

The significance of depleted southern landscapes must be understood within the much longer narrative of the region’s environmental history. Early settlers wrote poetically of the South’s fertile soil and abundant vegetation, evoking a New World Arcadia that promised the Jeffersonian ideal of yeoman prosperity. The opening of the Mississippi Territory in 1798 and the forced removal of Native Americans in the 1830s saw a rush of opportunistic homesteaders who, lured by virgin lands, left the eastern seaboard en masse to partake of the country’s burgeoning cotton economy. Within a few short decades, their overzealous deforestation and imprudent farming practices depleted the southwestern frontier’s soils and created devastating widespread erosion. A New England visitor to the region lamented as early as the 1880s:

Much damage has been done to the agricultural interests of the country by washing away of the surface soil. Over thousands of acres this process has gone on so long that nothing is left but the inert and unproductive clay, and this is cut up by gullies and chasms so wide and deep that they often have to be bridged like rivers.

Nonetheless, another fifty years of land mismanagement would follow, and by the 1930s more than 150 million acres—roughly half of the lower South—revealed acute signs of soil degradation.2

The South’s ecological woes were well documented in the popular press, geological field guides, and works of literature penned by local authors. William Faulkner, for instance, wrote evocatively of his “postage stamp of native soil,” indigenous terrain scarred by nearly a century of abuse. In novels such as The Hamlet, his mythological Yoknapatawpha County encompassed “old fields where not even a trace of furrow showed any more . . . and crumbling ravines striated red and white with alternate sand and clay.” Students of the interdisciplinary field of ecocriticism have found in the texts of Faulkner—along with those of Erskine Caldwell, Zora Neale Hurston, and other writers of the Southern Renaissance—a sort of cultural reckoning with the region’s natural environment but have had little to say about the period’s visual arts. An examination of works from the Cotton Belt states of Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia reveals, however, that for a select number of native sons and daughters, the wasted southern landscape offered a subject worthy of contemplation.3

To better understand the particular vulnerability of the region’s terrain, a brief lesson in pedology, or the study of soils, is first needed. The characteristic red clay soils stretching from the Piedmont to the Gulf Coast evolved millennia ago, a composite of intensely weathered minerals forged amid humid temperate conditions. While the discrete Mississippi floodplain and Alabama Blackland prairie comprised rich alluvial deposits optimal for agriculture, the majority of the South offered farmers only a modest layer of nutrient-poor topsoil atop a highly acidic substratum. The explosion of the cotton economy triggered by Eli Whitney’s 1793 invention saw the cultivation of large swaths of ill-suited earth with farmers tilling the land to exhaustion and then seeking unspoiled territory to begin the cycle anew. After the Civil War, market volatility and a diminishing frontier curbed this migratory practice, and growers confronted a new reality of stationary long-term monoculture. Governmental agencies and chemical companies alike promised that commercial fertilizers would ease the transition by replenishing the depleted southern soils, and initial harvests indeed proved bountiful. Such fertilizers, however, were regrettably finite as the additives lacked the necessary minerals, particularly nitrogen, to support long-term growth. As yields steadily diminished, farmers responded by using even more fertilizer, a measure that only worsened the soil’s chemistry. The practice of planting cotton in clean-tilled rows further contributed to the soil’s exposure by creating unimpeded conduits for heavy rainfalls, and within a few short decades, crevasses—some measuring more than a hundred feet deep and several hundred feet wide—split open across the region. The devastation reached an epidemic in the early 1900s South, roughly three decades before the ecological woes of the Dust Bowl and a worldwide economic collapse captured the country’s attention.

Fortunately, one of the first New Deal relief programs engineered by President Franklin D. Roosevelt was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), part of a comprehensive resource management initiative for rural America. Stationed at CCC work camps across the county, young unmarried men took part in reforesting public lands, constructing national parks, and, under the directives of early environmentalist Hugh Hammond Bennett, mitigating soil erosion. The Chapel Hill graduate and author of Soil Erosion: A National Menace had assumed leadership of the newly created Soil Erosion Service in 1933, driven in part by his upbringing amid the weathered terrain of Wadesboro, North Carolina, fifty miles southeast of Charlotte. The Great Plains’ epic dust storms, amply chronicled by historians and journalists, expedited the critical passing of the Soil Conservation Act two years later. But as environmental historian Paul Sutter has argued, it was ultimately the eroded southern landscape of Bennett’s childhood that provided the necessary foundation for the legislation. The government’s attendant media campaign, including feature films, radio shows, and a flurry of press releases, encouraged the public to help restore the local landscapes, and by the mid-1930s, schools across the country had incorporated studies of soil erosion into classroom curricula. In the South—described by Roosevelt as “the Nation’s No. 1 economic problem”—the CCC contoured and terraced farmland to minimize the deleterious effects of heavy wind and rain in addition to planting erosion-resistant crops and ground cover. Justification for such efforts reached East Coast policymakers through the documentary images of Walker Evans, Marion Post Wolcott, and Arthur Rothstein, photographers in the employ of the New Deal’s Resettlement Administration, later the Farm Security Administration. Purely aesthetic renderings would soon follow, encouraged in part by another Roosevelt relief initiative.4

FDR created the $4.8 billion Works Progress Administration (WPA) by executive order on May 6, 1935, to offer work relief to the nation’s unemployed. Within four months, the Federal Arts Project (FAP), a dedicated program within the agency, was established to provide paychecks to painters, sculptors, and photographers. More than ten thousand artists received FAP commissions during its nine-year existence, not only creating new works but also teaching classes and documenting material culture artifacts. The country’s largest ever program of government arts patronage, the FAP was also critical to the development of regionalism, an indigenous idiom that agency administrators encouraged due to its patriotic celebration of traditional folk values and rejection of European modernism. The native genre, also known as the American Scene, first arose within a cohort of midwestern artists who championed the depiction of local subject matter in an unassuming representational manner. It was within this particular nexus of eco-consciousness and regionalist expression that artistic depictions of the South’s depleted terrain emerged.

Such works were not wholly original. Artists a century prior had utilized ravaged landscapes to explore formal concerns of light and line as well as to offer trenchant social commentary. The earliest landscapes in the western tradition, those that elevated the natural world beyond mere background scenery, notably contained no such environmental destruction. Instead, the seventeenth-century works of French artists Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin presented carefully ordered pastoral scenes in which ancient temples and other monuments of antiquity suggested a kind of nostalgic ruin. Painters of the nineteenth century, considered the golden age of landscapes, rendered more complex works in which scenes of nature inspired both fear and reverence. Termed romanticism, the movement found its fullest expression in America within the Hudson River School, so named for its adherents’ favored locale in upstate New York. Its unofficial founder, Thomas Cole, employed both conventions, the pastoral and the sublime. At the same time, he developed an anti-pastoral visual rhetoric of moralizing scenes that warned against the encroachments of economic progress. Subsequent artists such as George Inness offered even more pointed critiques of the country’s ethos of Manifest Destiny but in more intimate compositions influenced by the French Barbizon School of the late 1800s.

Landscape painting in the Old Southwest followed a similar trajectory, yet its evolution in the region lagged behind Europe and the East Coast by several decades. Not only did inadequate roadways and a dispersed population limit most antebellum artistic activity to port cities like Natchez, New Orleans, and Mobile, but patrons consistently preferred portraits of themselves, their family members, and even their estates. The majority of landscapes from the early nineteenth century were thus typically journalistic with topographic illustrations serving as historical documentation of the frontier terrain. Indeed, as the Hudson River School flourished among a second generation of artists, including Albert Bierstadt, Jasper Francis Cropsey, and Frederic Edwin Church, Georgia painter T. Addison Richards bemoaned, “Little has yet been said, either in picture or story, of the natural scenery of the Southern States.” This quiescence continued throughout the Civil War as both patronage and basic supplies evaporated for the region’s artists. Only the dramatic battlescapes of Charleston Harbor executed by Confederates John Ross Key and Conrad Wise Chapman endure as notable depictions of the wartime terrain. Not until the Reconstruction period did the landscape genre finally take hold with practitioners Richard Clague, William Henry Buck, and George David Coulon. Their tranquil, light-filled scenes of moss-laden live oaks offered weary southerners a welcome respite from the graphic images of destruction captured through the emerging medium of photography. By the early 1900s, the next generation of artists had forgone this “moonlight and magnolias” trope, but their landscapes still betrayed elements of Lost Cause romanticism that rampant erosion of the rural interior would complicate.5

Mississippi native John McCrady yielded what is perhaps the period’s most vivid pictorial record of southern soil erosion. His compositions—revealing the influence of Thomas Hart Benton, who himself recorded the region during a 1928 driving tour—primarily depicted genre scenes of north-central Mississippi’s Lafayette County, where the artist had spent his adolescence. Straddling the fertile, silt-covered Loess Hills and red clay Upper Coastal Plain, the countryside had been cultivated for cotton since the 1830s. But when McCrady’s father assumed an Episcopalian rectorship in the county seat of Oxford roughly a century later, much of the scarred terrain lay fallow—as potently documented by FSA photographer Walker Evans during a 1936 visit. McCrady, an alumnus of New York’s Art Students League, frequently rendered the environmental depredation in paintings that demonstrated his religious upbringing as well as his fluency in the western tradition, especially works by the old masters. His Oxford on the Hill from 1939, for example, depicts the town upon a denuded, dramatically furrowed hilltop patently in the manner of El Greco’s late sixteenth-century View of Toledo. While dark, sinuous clouds cast shadows upon the landscape, faint streams of light illuminate the proverbial “city on a hill.” In McCrady’s 1940 Sic Transit, from the Latin recitation sic transit gloria mundi or “thus passes the glory of the world,” an aging Victorian home stands alone on the deeply crevassed red earth, visualizing on canvas a scene penned just two years earlier in the government-funded travel book Mississippi: A Guide to the Magnolia State:

A great many crumbling mansions, built during the flush times of the 1830s and 1840s, desolately face the encroaching gullies. These houses, gradually mouldering away as the earth slides from beneath them, are unpainted with sagging porches and rotting pillars.6

Our Daily Bread, also from 1940, presents a more charming vista employing the pastoral conventions of Claude Lorrain: a lone foregrounded tree, a meandering body of water, crepuscular light from a setting sun, and a narrative of peasant life. Alluding to the venerated Christian prayer, the title suggests the earth’s bounty even while a defoliated tree appears destined for the adjacent woodpile and a corrugated gully slowly drains the land’s precious water supply. The receding terrain foretells the displacement of its few inhabitants, but McCrady’s warm palette and soft curvilinear forms render a scene of comfort and serenity.7

Buell Whitehead’s Erosion offers a stark juxtaposition to McCrady’s representation and to his own collection of light-filled lithographs inspired by the abundant flora and fauna of his native Florida. During visits with family members across the state line in southeast Alabama’s Geneva County, he observed foreboding, eviscerated landscapes that plagued many areas of the East Gulf Coastal Plain, an expanse of roughly forty-two million acres stretching from southwest Georgia to the eastern portion of Louisiana. In Whitehead’s 1940 painting, a cleft bisects the county’s characteristic red clay soils, allowing engorged earthen bowels to spill out into a murky pool of bluegray water. On either side of the chasm, a modest two-story farmhouse and cluster of severed tree stumps make clear that the erosion is man-made. The homestead itself leans precipitously on a sloped embankment with only a post-and-wire fence preventing its subsidence into the deep laceration below. In Alabama Road, his 1946 lithographic reinterpretation of the painting, the foregrounded signpost reads “Dothan” and “Black,” confirming the composition’s Geneva County origins.

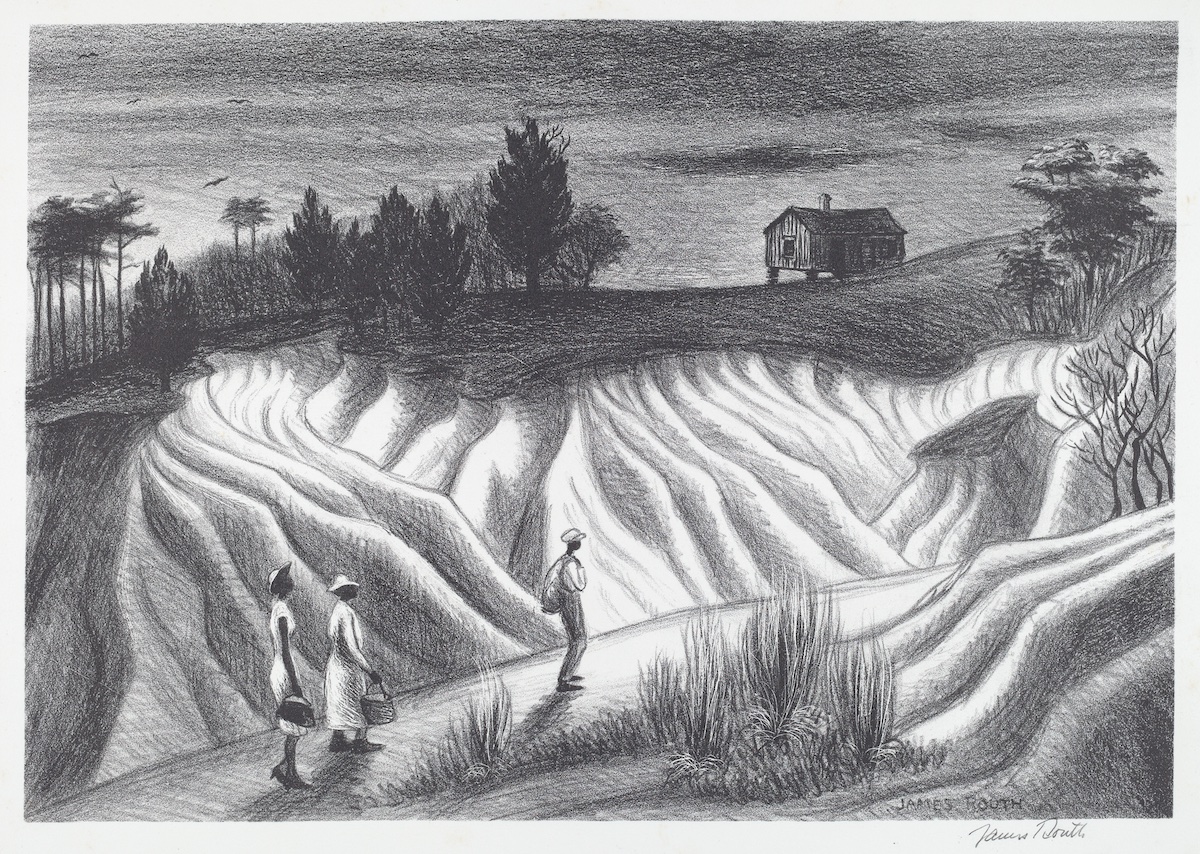

Atlanta artist James Routh also used the title Erosion for his 1940–1941 lithograph based on sketches from a year touring the region with support from the Rosenwald Foundation, a Chicago-based philanthropy that distributed monies to black artists, writers, and scholars plus whites like Routh whose work demonstrated a concern for issues of race. The $1,500 stipend supported, according to an organizational report, “creative work . . . especially to depict [the] Negro and rural scenes in the South.” Unlike Whitehead’s intensely colored painting, Routh presents a calming monochromatic lithograph in which the severely eroded terrain appears to softly undulate. A humble raised cabin sits atop the swath of vanishing hillside and three diminutive African American figures quietly traverse the dirt road, perhaps en route to church or town. Similar to the artist’s other works from the period, the landscape dominates the composition, suggesting impoverished southerners’ relative powerlessness in curtailing the environmental damage. More dramatically, Routh’s Chimney, also from 1940, presents only the remnants of human life: a desolate smokestack long bereft of its attendant dwelling. Photographer Marion Post Wolcott had captured a nearly identical scene the previous year while working for the Farm Security Administration in Greene County, Georgia, just seventy miles east of Atlanta; but in aesthetic terms, Routh’s print recalls the work of early nineteenth-century German Romanticist Caspar David Friedrich. For both artists, growing vegetation evoked a return to nature and even rebirth, but the extensive soil erosion rendered in Chimney cuts short this promising visual narrative.8

Georgia Red Clay, a 1946 painting by native daughter Nell Choate Jones, presents a vibrant Van Gogh-esque expanse of striated, copper terrain intermittently framed by a derelict rail fence and segmented by a pair of twisted, ropelike trees. The daughter of a former officer in the Confederate Army, the artist hailed from Pulaski County on the edge of Georgia’s fertile Black Belt but, following her father’s death in 1887, moved with her mother to Brooklyn, New York. Jones began periodic journeys home beginning in the 1930s, by which time widespread cotton tenant farming had left deep scars in the county’s red and yellow sandy clay soils. While figurative renderings and genre scenes of southern African American life characterize her work from the period, Georgia Red Clay conspicuously omits the human form from the rural scene’s environs. It appears no less lively, however, as the artist’s animated brushwork allays the exhaustion of the rust-hued earth. Like McCrady, Jones saw erosion in pictorial, not moralistic, terms, leading an ARTNews critic to write in April 1945, “It is the picturesqueness of the South . . . rather than the import of its social conditions, which concerns her.”9

The works of Hale Aspacio Woodruff, in contrast, unapologetically assert a social critique with fraught landscapes and charged compositional elements. Raised in the historically Black working-class community of East Nashville, Woodruff attended school at the Herron Art Institute in Indianapolis and then moved to Paris for four years, where he became immersed in the groundbreaking early modernist idioms of Paul Cézanne. Woodruff joined the faculty of Atlanta University (now Clark Atlanta) in 1931, finding ample inspiration in his new surroundings. “There is much rich material in Atlanta, and the Georgia landscapes are as fine as could be desired by any painter seeking subjects for his work,” he genially commented in 1934. He realized such observations in paintings including Southland, a surrealistic depiction reminiscent of Routh’s Chimney, in which the skeletal remains of a house stand amid a postapocalyptic landscape of barren red soil, jutting rock formations, and dead trees. His 1936 Untitled comparatively offers a less savage composition of gently undulating hills and a placid cloud-strewn sky, but the expanse of furrowed red earth, pockmarked grazing pen, and tombstone-like scattering of tree stumps—the latter recalling George Inness’s The Lackawanna Valley from 1855—suggest the land’s overuse.10

Increasingly attuned to environmental racism, Woodruff soon sought vistas beyond central Georgia in order to study the deleterious effects of soil erosion on rural-dwelling African Americans. He reflected in a 1943 application to the Rosenwald Fund, his second monetary request to the philanthropic organization, “The southern landscape is romantically picturesque, but more significant is the state of the land with its erosions and sterility and their effects on the Negro peasants.” Initially rejected by the foundation due to his modernist leanings, Woodruff found success with his later proposal, receiving a two-year fellowship to document impoverished African American tenant farmers. The artist moved to New York with his stipend but spent the summer of 1944 in Mississippi working from a studio on the campus of Jackson’s Tougaloo College. Two notable landscapes resulted from this southern sojourn: Mississippi Wilderness and Erosion in Mississippi. The former presents a richly hued yet uninhabitable environment of craggy bluffs and bowed inert trees. That the land can no longer support life is indicated by an African American child who flees the scene carrying a gardening tool; a sun-bleached skull from a long-expired beast of burden underscores the aura of death. Erosion in Mississippi presents a hallucinatory composition of churning bluffs and denuded arboreal forms that appear to careen and topple into the ravine below. The more muted pastel on paper serves as an ostensible sequel to Mississippi Wilderness, as it bears no trace of human activity. The following year, Art Digest aptly wrote of Woodruff, “The southern land, twisted by erosion into fantastic, tortured shapes, has been his subject for many years and continues to interest him … [His paintings] make use of the soil’s revolt against misuse.” Woodruff ultimately executed his own personal revolt against the South, long twisted and tortured by racism, by permanently relocating to New York in 1946.11

Woodruff, more than his white artistic counterparts, understood that the region’s starkly eroded landscapes disproportionately burdened rural African Americans, but the ubiquity of the battered terrain made it a compelling subject for individuals on both sides of the color line. Artists like John McCrady, Buell Whitehead, James Routh, and Nell Choate Jones made good use of the furrowed ground, creating moving compositions that laid bare the severity of the land’s woes, making the Arcadian live oak landscapes of previous generations seem trite and anachronistic. Yet their stylized, often sentimental renderings and selective deployment of Black figures masked the desperation of many tenant farmers. Ultimately, the conventional genres of the western canon fell short as neither the devices of the Claudian pastoral nor the conceits of Hudson River School romanticism, both at play in the white southerners’ works, provided an adequate visual vocabulary for representing the humanitarian crisis.

Only Hale Woodruff—an African American artist raised in the South and schooled in the then-radical aesthetic of Paul Cézanne—began to capture “the soil’s revolt against misuse.” His lived experience made clear the unsustainability of the region’s environmental and societal ills, and he deftly employed a revolutionary pictorial idiom to record his observations. Marred by the ecological ruin and racial injustices of its agrarian past, the twentieth-century South struggled to find its way in the face of industrialization and the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement. For individuals like Woodruff, however, the topographical and psychological scars were too deep and, to employ an apt colloquialism, “greener pastures” elsewhere beckoned. The South’s slow acceptance of modernism further accelerated the exodus with artists seeking proximity to more cosmopolitan environs—in particular New York, which had surpassed Paris as the epicenter of the art world following World War II. Those who remained loyal to more traditional representational modes of expression attracted local viewers, but outside of the South their works appeared quaint and outmoded. Only a notable few like Charleston’s William Melton Halsey and New Orleans’s Paul Ninas fully embraced the new aesthetic. Others experimented, albeit reluctantly, with abstraction; some gave up their practice altogether. Such was the case for John McCrady, who, rather than appease East Coast audiences, immersed himself in teaching at his eponymous French Quarter art school while like-minded James Routh left his studio to become a commercial artist for an Atlanta advertising agency. Whatever their chosen path, southern artists, like their peers across the nation, abandoned the regionalist idioms of earlier decades.

Postwar landscapes also changed in subject matter partially due to the successful initiatives of the New Deal. The Soil Conservation Service made expansive scenes of gully erosion a thing of the past with the implementation of science-based farming techniques and the widespread planting of kudzu. The creeping perennial vine from Asia promised to restore nitrogen to depleted soils while also providing much needed ground cover. With no natural predators to thwart its growth, however, the invasive species soon blanketed the region to become an environmental nuisance in its own right. Amorphous, leafy forms—built upon an irregular scaffolding of vacant buildings, discarded appliances, and conquered telephone poles—quickly veiled the southern landscape, making the plant an appealing subject for artists. Of these, photographer William Christenberry created the most significant body of work with chromogenic prints recording the plant’s inexorable growth in his native Alabama. Like those who depicted the South’s catastrophically furrowed terrain in the thirties and forties, Christenberry and his late twentieth-century peers found visual poignancy in nature’s beauteous ruin.

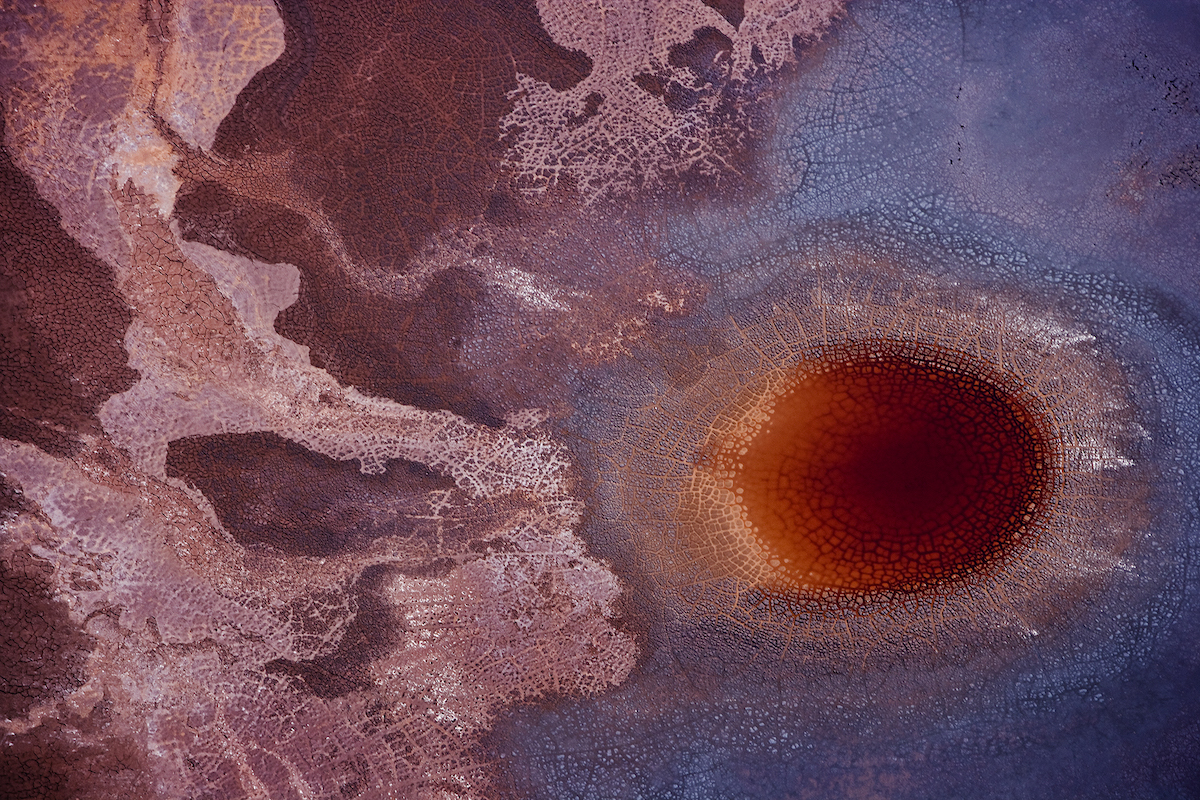

The rightful heirs to the South’s anti-pastoral landscape tradition, however, are found among artists such as Monique Verdin, who have begun to aggressively document the negative environmental impact of industry in the region. An examination of the pictorial record even reveals that this particular focus has precedent: James Routh interspersed his depictions of soil erosion with somber lithographs of the towering smokestacks of Atlanta’s Dixie Steel, and Georgia native Lamar Dodd included in his regionalist output foreboding scenes of copper mining in Tennessee. More recently, Mississippian William Dunlap created his Agrarian Industrial Complex series showing chemical plant cooling towers set uneasily amid the placid topography of Old Dominion. Today, however, a growing number of artists like Verdin have resolutely put ecological destruction at the forefront of their creative practice. Charleston native J. Henry Fair, for example, has yielded an expansive body of aerial photographs showing environmental damage in intensely colored compositions that recall abstract expressionist paintings from the previous century. Since capturing the pollution of the Mississippi Delta in 2001, Fair has gone on to record the toxic waste of south Louisiana’s petrochemical plants, the devastation of the Deepwater Horizon spill in the Gulf of Mexico, and the toll of the coal industry in Appalachia, among other sites worldwide. Similarly, New Orleans artist Dawn DeDeaux addresses nature’s precarious condition in works such as Project Mutants, The Goddess Fortuna, and The MotherShip Series. Her Lostscapes: The Killing Fields specifically explores the rapidly disappearing coastline of her home state in a multimedia installation of large panoramic panels. With the crisis of global warming and its attendant rise of ocean waters and increase of extreme weather patterns, more southern artists will undoubtedly find cause to comment on the earth’s dramatically changing physical landscape.

The New Deal–era artists may have been comparatively less self-conscious in their environmentalism, but their creations nonetheless bear witness, providing an enduring record of humans’ misuse of the land. Like the oft-reproduced images of the 1930s Dust Bowl, the works poignantly conjure the past to offer an immediacy that written texts alone often lack. Renderings of southern soil erosion deserve greater consideration as they tell an important story of ecological woe that, predating the Great Plains’ barren fields by decades, nearly paralyzed a region still recovering from the devastation of the Civil War. The works also add to our present understanding of the South’s intergenerational poverty as most tenant farmers lacked the means to leave or the knowledge to rehabilitate the depleted terrain. Their offspring have received a sad inheritance of conservation ignorance and limited opportunity exploited by today’s extractive industries. With environmental justice eluding many of the region’s disadvantaged inhabitants, the need for incisive and innovative visual commentary—along with CCC-style governmental intervention—becomes more urgent. Just as Eudora Welty’s protagonist in Death of a Traveling Salesman “saw that he was on the edge of a ravine that fell away, a red erosion, and that this was indeed the road’s end,” a growing number of southern artists understand that the region is rapidly approaching an environmental precipice. We must hope that their compositions awaken a broad eco-consciousness that demands new avenues of sustainability.12

This essay first appeared in the Backward/Forward Issue (vol. 25, no. 1).

Teresa Parker Farris is an interdisciplinary scholar at Tulane University, where her research focuses on the history and art history of the American South. The former deputy director of the Newcomb Art Museum, she writes regularly about the South’s visual arts, both folk and fine, as well as its vernacular cultural traditions.NOTES

- Deirdre Fulton, “Gulf Coast Activist Crashes Shell Meeting to Decry Destruction of Her Home,” Common Dreams, May 24, 2016, commondreams.org/news/2016/05/24/gulf-coast-activist-crashes-shell-meeting-decry-destruction-her-home.

- Jonathan Baxter Harrison, “Studies in the South,” Atlantic Monthly, June 1882, 743–744.

- William Faulkner, “The Art of Fiction XII: William Faulkner,” interview by Jean Stein, Paris Review, no. 12 (Spring 1956): 52; William Faulkner, The Hamlet(New York: Vintage Books, 1991), 190.

- Paul Sutter, “The Southern Origins of Soil Conservation,” We’re History, April 27, 2016, werehistory.org/soil; Franklin D. Roosevelt, “The President’s Letter,” in Report on Economic Conditions of the South, ed. The National Emergency Council (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1938), 1.

- T. Addison Richards, “The Landscape of the South,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, May 1853, 721.

- Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration, Mississippi: A Guide to the Magnolia State (New York: The Viking Press, 1938), 440.

- Works Progress Administration, Mississippi: A Guide to the Magnolia State (New York: Viking Press, 1938), 440.

- Edwin R. Embree, Julius Rosenwald Fund: Review for the Two-Year Period, 1938–1940 (Chicago: The Fund, 1940), 32.

- “The Passing Shows,” ARTNews, April 15, 1945, 6.

- Ralph McGill, “Hale Woodruff,” Atlanta Constitution, December 18, 1934.

- Hale Woodruff Fellowship Application and Statement of Plan of Work, 1943, Julius Rosenwald Fund Archives, Special Collections, Fisk University Library; and Judith Kaye Reed, “Hale Woodruff,” Art Digest, April 15, 1945, 15.

- Eudora Welty, “Death of a Traveling Salesman,” The Collected Stories of Eudora Welty (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1982), 120.