On a September evening in 1934, Dr. J. Max Bond, the highest ranking African American official of the Tennessee Valley Authority, delivered an address to the Personnel Division Conference of the TVA. The federally owned TVA had launched the previous year, promising to bring social planning and electricity to the many rural and impoverished residents of parts of Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky. Bond discussed the TVA‘s wage disparities between Black and white workers, and asserted that the lower wages paid to African American laborers resulted in lower corresponding wages paid to whites who had previously done the same jobs. He further stated that if Black workers received higher wages, their buying power would increase, further stimulating the region’s economy. Bond then turned his attention to the crafts made by African American women in the TVA community:

The ladies in our village have struck upon the idea of developing [Black] art. They are securing the services of some of the [Black] women who know rug and quilt making. The designs on the quilts are depicting different phases of [Black life]. . . . One of our artists is studying the type of work that is being done on the job. . . . It is modernistic. . . . It will be something to indicate that we are proud of [African American] . . . art . . . 1

Why would a TVA official discuss quilts in recorded remarks about the “racial problem” at an official meeting of administrators? Max Bond perceived this proposed craft project as a potential source of empowerment to the TVA staff and their families, and as a signal to his federal higher-ups that Black workers had much to offer the community and nation and deserved better treatment than the federal program was providing.

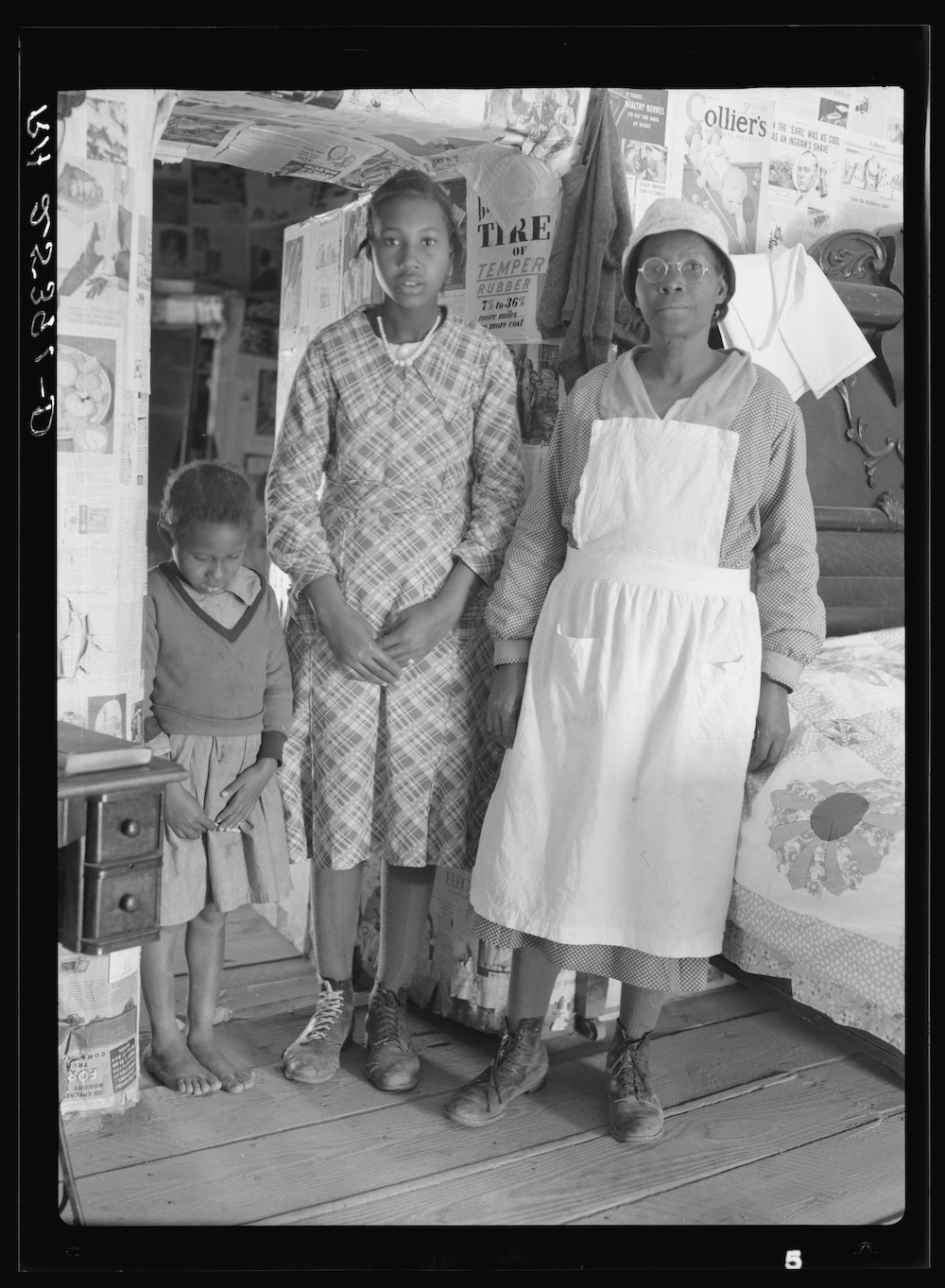

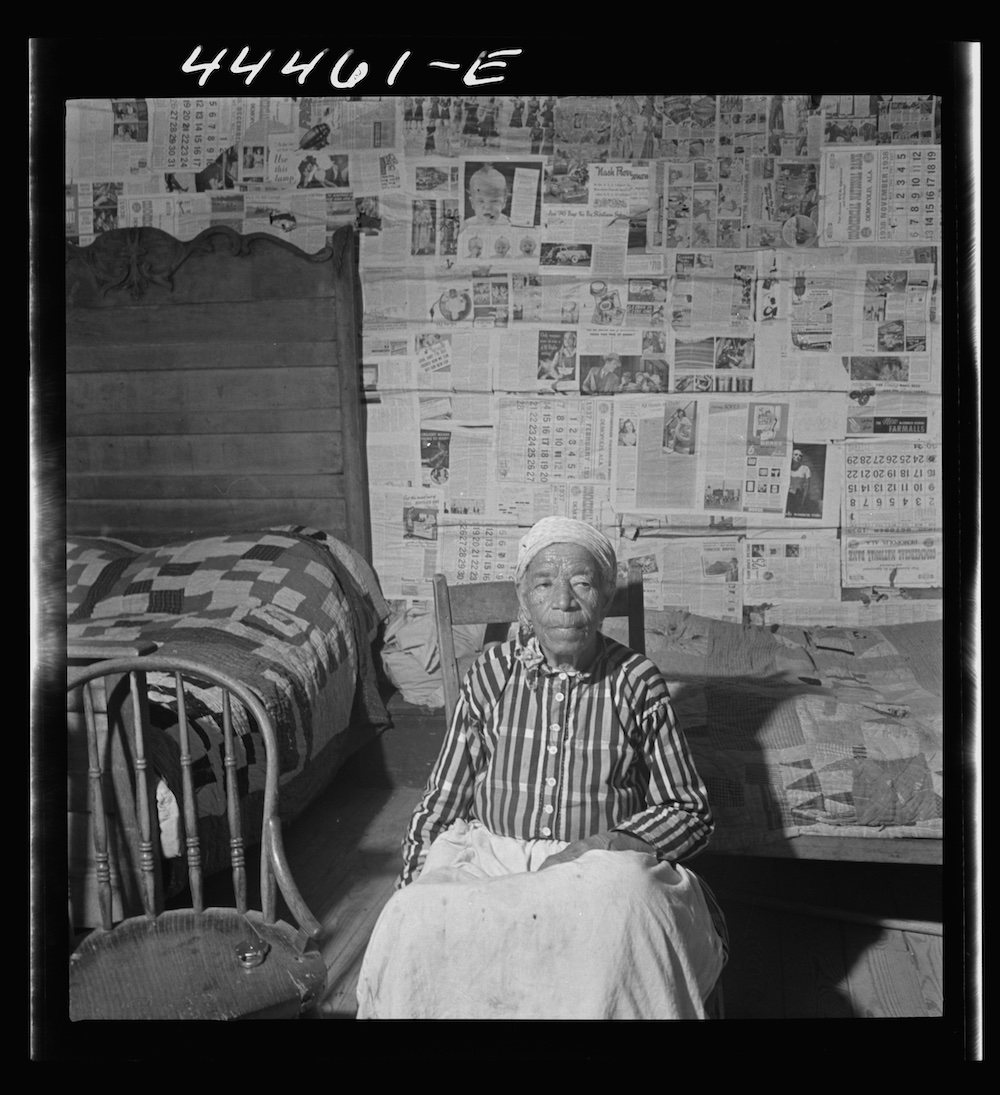

Bond also had a personal investment in the quilts and related crafts made by the wives of TVA workers. His own wife, Ruth Clement Bond, had orchestrated the project. She conceived of the quilts as part of what she called a “home beautification” initiative aimed at sprucing up the low-grade government-issued housing of the African American families associated with the project. Like most of the South, the TVA project workforce was segregated, as was the village with housing for workers building Wheeler Dam where the Bonds lived. Ruth imagined an alternative to papering the walls of cottages with Sears catalog pages, as many of the transplanted African American women who relocated from sharecropping farms to the construction villages did. She proposed that each cottage have what she called a “TVA room” that the women could decorate with furnishings from local resources, including curtains made from flour sacks donated by the TVA commissary cook, rugs woven from dyed corn husks, and furniture made from local willow trees. Ruth herself created modernist quilt designs, drafting patterns on brown paper that she shared with other Black women in the various TVA workers’ villages so that they could make empowering quilts for TVA rooms of their own.2

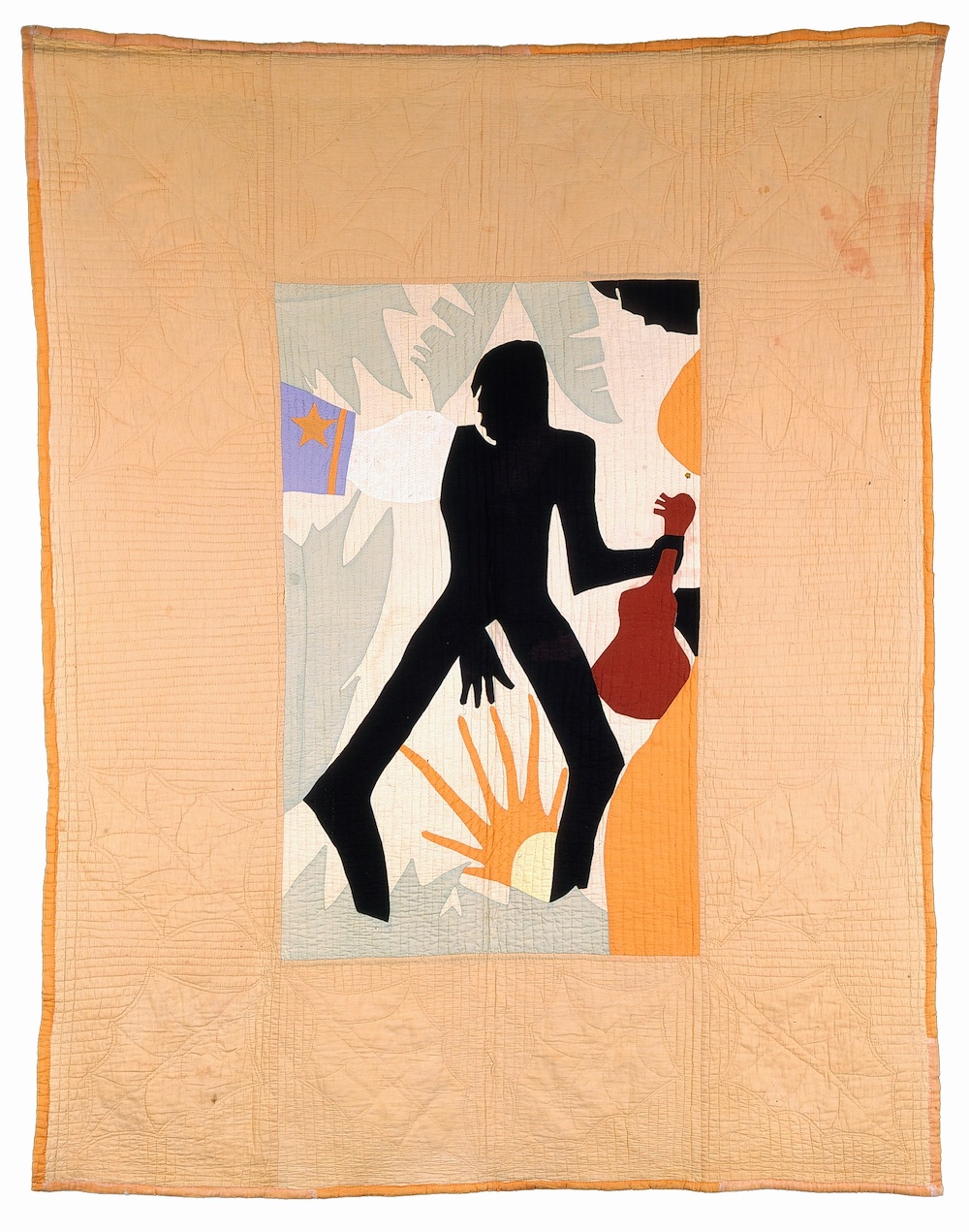

Ruth Bond designed at least three quilts, all of which have at least one extant example, and a fourth which she described in a 1992 oral history. One quilt, which has at least five known copies, features an appliqué of a silhouetted man holding a musical instrument in his left hand. A Black hand from a woman’s body reaches toward him and a white fist sticks out of a blue sleeve with starred cuff to touch his right shoulder. Surrounding the figure are leaves and vegetation, with a sun rising from beneath his legs. Exemplary of the quilts’ shifting status and interpretation, this design goes by several names; some of the wives of TVA workers dubbed it “Lazy Man,” but years later the TVA preferred the name “Uncle Sam’s Helping Hand.” Ruth Bond used neither title in the oral histories she gave decades later.3

Ruth Bond’s design for Lazy Man speaks to the dual purposes of New Deal programs—reliance on government and self-reliance, with the African American man torn between taking government assistance and enjoying his leisure. Her figurative motifs conveyed those qualities by symbolically representing the two meanings of power: the empowerment of a community acting with agency and the actual power provided by the federal dams. Quilts already had a clear connection to self-reliance, widely celebrated in popular culture as exemplars of creative reuse and thrift. Both the government and American quiltmakers symbolically drew on myths of colonial-era fortitude and self-sufficiency as a means of overcoming poverty. Quilts and quiltmaking were having a heyday in the 1930s, due in part to a nostalgia-fueled colonial revival spurring thousands of commercially available patterns, quilting columns published in local newspapers and ladies’ magazines, and widespread fascination with mythologized quiltmaking practices of previous generations. The colonial revival, sparked in part by the American Centennial in 1876, and its subset quilt revival, may have originated with white middle-upper class interest in colonial America, but by the time of the Depression, quiltmaking had become democratized and accessible, with widespread availability of patterns and creative scrap quiltmaking out of necessity. With the economic conditions of the Great Depression, many women ingeniously repurposed cloth from their scrap bags, combining bits of old clothes with recycled cotton sacks that packaged sugar, flour, or feed into bedcovers. American quiltmakers—whether educated women like Ruth Bond who drew on modernist design, makers who created quilts based on patterns featured in syndicated newspaper columns, or grassroots quilters who turned to their scrap bags to piece together innovative bedcovers to keep their family members warm—imagined in the quilts and quiltmakers of early America an ingenuity of making do to create something beautiful and functional. Quiltmaking became a popular Depression-era hobby as it kept hands busy while drawing on the mythology of colonial America and acting out 1930s values of thrift and perseverance.4

These clear symbolic connections between quiltmaking and the values the federal government promoted as part of its agenda resulted in recurring uses of quilts in New Deal initiatives. Some Works Progress Administration (WPA) sewing rooms employed women to make quilts. Hundreds of Farm Security Administration photographs, which the government used to cultivate empathy for its programs, feature women posed making quilts or quilts in use in domestic spaces. Women created blue eagle–themed National Recovery Act quilts in support of these laws protecting workers. And projects under the umbrella of the larger Federal Art Project—the Index of American Design, the Museum Extension Project, and various Federal Writers Project endeavors—documented historical quilts and quiltmaking practices. It is no coincidence that quilts’ popularity increased during the economic downturn and the federal response to it. In an era of scrimping and saving, American culture’s nostalgia for the craft of quiltmaking made sense, and New Deal programs capitalized on this as well.5

Ruth Bond’s quilt designs, however, shared little in common with the cheery scrap quilts in patterns such as Double Wedding Ring and Grandmother’s Flower Garden that were popular among Depression Era quiltmakers. Bond recalled that her first design—sadly with no known examples—featured a full-length Black worker holding a lightning bolt in his hands. Another of the quilts similarly portrayed the symbolic power of electricity through a lightning bolt, this one with a fist reaching out of the ground, similar to the TVA‘s early logo, which appeared with the motto, “Electricity for All.” Supposedly, some of the quiltmakers as well as college interns working for the TVA called it the “Black Power Quilt,” with late twentieth-century observers speculating that these quilts introduced the phrase “Black power” to the American lexicon. The final design of the series depicted a man working with a crane overhead, representing African American workers building a dam. Bond gave women in the TVA‘s “Negro Villages” the pattern, drawn on brown paper, and suggested the colors for the design. It’s unknown how many women made how many quilts, but a few now reside in museum collections and have identified makers.6

According to the TVA, in 1935 Max Bond presented one of these quilts to TVA chairman Arthur Morgan, one of the three white male members of the board of directors. This was one of two TVA quilts that African American administrators in the TVA gave to their white federal TVA superiors, with a Black women’s group presenting a third quilt. The gift of these modernist quilts with clear African American motifs to white federal TVA administrators was a symbolic gesture intended to evoke the empowerment and economic potential of the Black residents in the South, in order to encourage executives to support efforts of integration and equality. TVA records state that in presenting the quilt to Morgan, Bond wrote:

As you know, the wives of the workers in the Muscle Shoals area are organized into clubs, into what we call TVA clubs, seven in number. One of their projects is an attempt to revive the arts and crafts that were known to [African Americans] during slavery. They further are attempting to use their handicraft to express the part that [Black people are] playing in changing the South.7

Ruth and Max Bond were well-educated, came from affluent families, and had lived and attended integrated universities in Chicago and Los Angeles. After working in Kentucky for the Julius Rosenwald Foundation—a philanthropic organization focused on civil rights—the TVA recruited Max to serve as a supervisor, with a job description to “plan and promote useful training programs based on the specific needs of [Black] employees.” The Bonds relocated from Los Angeles, where Max was finishing his doctorate at the University of Southern California, to Wheeler Dam in Jim Crow Alabama. His job became liaising between Black TVA workers and the federal agency employing them. As a civil rights advocate, he navigated a delicate path, publicly showing support for TVA policies while internally critiquing the agency’s discriminatory practices, including the exclusion of African American workers from its Norris Model Community (a construction town at the Norris Dam site designed as one of many New Deal planned communities) and other sites, separate pay scales for Black and white workers, and segregated housing and services that were nothing close to “separate but equal” in quality.8

With its location in the rural South, where most African Americans still lived at that time, the TVA had one of the worst records on race compared to other New Deal initiatives. Many former sharecroppers found work with the TVA, sometimes earning cash for the first time. Despite becoming the largest employer in the region, the TVA placed most of its Black employees in menial and temporary jobs, and it struggled to live up to its 1934 promise of employing African Americans in proportion to their population percentages in the region. Yet the structural racism that defined the era and most federal programs resulted in segregated and often substandard housing for TVA‘s African American workers, with many Black residents in the region not benefitting from its amenities, such as recreational facilities. Furthermore, the quarter million rural African Americans living in the region did not benefit from the social planning promised by TVA in the form of a “planned and rational economy,” with many white landlords initially refusing to wire Black tenants’ homes despite the newly implemented policies of rural electrification. As the Crisis, the magazine of the naacp, reported in 1935, “These men are used to segregation and to prejudice. But they are not used to [it] at the hands of the federal government.”9

At Wheeler Dam, where the Bonds were based, the village housing African Americans was comprised of a dormitory for Black male workers and ten separate houses for Black families. In contrast to the white village, located on a scenic bluff overlooking the dam, the Black workers lived in swampy woods. White families had access to a school, library, theater, park, and tennis courts, while Black families could use one tennis court and a combined dining and recreation hall. Similar disparities existed at Wilson Dam. Housing conditions were somewhat better at Pickwick Dam, but the village for Black families was in a location prone to flooding, accessible only through a road that ran through a squatter village with brothels, gambling houses, and speakeasies.10

As Ruth Bond drove from village to village, visiting the homes of other TVA families, she became fascinated by the quilts the wives made. In a 1992 interview, she noted that these women, previously sharecroppers and now transplanted to the TVA workers’ villages, had learned quilt-making from their enslaved ancestors, who told stories through their quilts. The quilts that she saw likely fell into one of two categories: quilts like those that Grace Tyler, a prolific and skilled quiltmaker, made in the popular and widely circulated patterns of the day (Double Wedding Ring, Grandmother’s Flower Garden, Dresden Plate); or inventive scrap quilts pieced in simple graphic shapes, often from recycled fabrics. Ruth Bond, who earned her BA and MA in English, had never made a quilt herself. But she had the idea that quilts could represent the story of rural electrification and African American empowerment. She did not draft conventional or easy-to-execute patterns; rather, she designed challenging appliqué motifs drawing on the community’s relationship to the TVA.11

In design, content, and construction, these quilts are more akin to the works of contemporary African American artist Aaron Douglas than quilts made with the numerous commercially available patterns. Grace Tyler recalled that a painting that hung at Fisk University by an African American artist inspired Ruth Bond’s design, likely part of Aaron Douglas’s mural series depicting the historical stages of African and African American life. In her interview with Merikay Waldvogel, Bond did not recall using Douglas’s work as a model, although she admitted that the figure holding the musical instrument in Lazy Man“does have certain Douglasesque elements” including treatment of the silhouetted man with slits for his eyes. Bond’s male figure on Lazy Man also has angular shoulders and knees with lush vegetation framing the composition, both elements found in Douglas’s Fisk murals. Bond noted that her quilt designs also share similarity with Henri Matisse’s flattened abstract human figures, which also influenced Douglas. In addition to this visual resemblance, Bond’s quilt designs shared some of Douglas’s goals, such as his celebration of Black music and labor. In many ways, it is no surprise that her patterns resemble these modernist paintings more than contemporaneous quilts; these were designs by a civil rights activist and educator with advanced degrees, who was familiar with cutting-edge African American art, rather than someone well-versed in needle and thread. Despite Bond’s reluctance to directly credit Douglas as inspiration, she most likely was familiar with his famous murals at Fisk University, which received acclaim upon their completion. Douglas produced this series of paintings in 1930, when the Bonds were living in Los Angeles, and while Max’s brother Horace Mann Bond worked in the sociology department at Fisk. One of the TVA quilts—its whereabouts now unknown—was even pictured in the Crisis with the caption “Rugs made by wives of TVA workers in Muscle Shoals area. Motif from Aaron Douglas.”12

In addition to the quilt Max Bond presented to Arthur Morgan, Grace Tyler recalled that in 1934 her husband, Harry Winston Tyler, who served as the junior personnel representative reporting to Max, gave one of her quilts with the fist gripping the lightning bolt to the young progressive TVA board member David Lilienthal, who later served as its director in 1941. Grace Tyler recalled being upset when her husband returned home without the quilt. Like Arthur Morgan, Lilienthal carried out TVA‘s discriminatory policies in hiring and housing, although he couched these practices in the organization’s emphasis on grassroots participation, which to him included the Jim Crow practices of southern white workers and labor unions that would not admit African Americans as members. He perceived the TVA‘s segregationist policies as merely part of the culture of the region, rather than something the agency could effectively sweep away through policy.13

A third TVA administrator, Maurice Seay, also received a quilt as a gift, but not from a Black male TVA employee who gave away a prized quilt without permission from his wife. Seay, director of the TVA‘s educational programs, recounted that the president of the Negro Women’s Association at Pickwick Dam Village presented him with the quilt to mark that “for the first time in the history of Mississippi, so far as she knew . . . black people and white people had studied and played together in an integrated educational and recreational program built and supported by public money.” Seay recalled that although workers lived in segregated villages on opposite sides of a ridge, the integrated facilities were a novel and unifying feature of the Pickwick community, with activities and training for residents of both races, and that the women had presented the “specially designed, homemade quilt” in gratitude for his role in directing these programs. He explained what he understood of the symbolism of the quilt: “A black boy being urged as indicated by the governmental arm of a white man to work hard and obey the law, while at the same time the guitar held in his left hand, symbolic of fun, leisure, and frivolity, was suddenly urging him to a life of frivolous living.” Seay’s dichotomy between the “black boy” and the “governmental arm of a white man” implies the clear hierarchy among races and the power Seay perceived the federal administrators had over TVA employees. Of this same quilt design, Rose Marie Thomas, the only identified Pickwick quilter, said, “It tells the story of what was happening for the black man on the TVA dam construction sites. . . . He is between the hand of the government and the hand of a woman. He must choose between the government job and the life he has known.” Both Seay and Thomas recognized that the quilt represented a choice that Black workers made by joining TVA work crews, but Seay’s interpretation gives much more agency to the white hand of government in directing African Americans to the path of hard work and lawfulness. In contrast, Ruth Bond described the significance of this pattern as a positive and empowering message: “Things were getting better, and the black worker had a part in it.” Of the white hand, she noted, “It represents the black man moving away from the hand of the law. In spite of the law, he is moving to become independent and to become an important part of society.” Each individual offered an interpretation decades after the completion of the quilt, and no doubt their analyses were colored by the known successes of the New Deal and the Civil Rights Movement, as much as the realities of what it felt like to live in a segregated construction village in the 1930s.14

Despite Seay’s recollections of integrated facilities at Pickwick Village, further documentation reveals that much of life here remained segregated, suggesting that Seay did not fully appreciate the reality Black families at Pickwick experienced, and perhaps misunderstood the purpose of the quilt as gratitude, rather than as a gift intended to persuade white administrators that the Black families of the TVA deserved more than segregated Jim Crow facilities. The naacp reported in 1935 that Pickwick had a “Jim Crow” section in its movie theater and doors to the personnel office marked “white” and “colored.” TVA officials stated that there would be “racial outbreaks” if African Americans and whites lived together at Pickwick. The “Negro Village” was inferior in a number of ways, with few temporary houses compared to the mix of permanent and temporary in the white village. A segregated combined cafeteria and community center was available for Black workers’ families, although the food was prepared in the white cafeteria and delivered to the Black village. The hospital had a separate ward for Black patients. A Pickwick resident recalled that, upon Eleanor Roosevelt’s 1937 visit to Pickwick Dam, she was overheard saying, “The signs on these rest rooms will surely be changed soon,” in response to the “colored” and “white” labels. White residents could participate in a variety of recreational activities in the white community building, including basketball, chess, volleyball, and boxing, and join various clubs and attend weekly dances. Residents in the Black village had a few similar options, like ping-pong, checkers, and dominos, but did not participate in team sports as white residents did, because there were too few of them to field teams and they were not allowed to play with their white counterparts. As was the custom in this region, Pickwick schools remained segregated, with the school for Black children ending at eighth grade, while white children could attend through high school. “We have the tragic picture of officials of the federal government, sworn to uphold the Constitution, teaching white citizens that [Black people] are unfit to live in any but segregated communities,” wrote John Davis of TVA‘s segregationist policies in the Crisis.15

Rose Marie Philips Thomas lived with her husband Wesley Marion Thomas at the Pickwick Village during construction of the dam. While it is unknown if Rose Thomas was a member of the Negro Women’s Association, with Pickwick’s small population of Black families—only twenty-five temporary houses were available for Black families compared to fifteen permanent and eighty-five temporary homes for whites—it is likely that she participated. We do know that despite having no experience with quilting, Thomas executed three small cloth appliqué blocks using Ruth Bond’s designs. She also made her one and only full-size quilt in the Lazy Man pattern, quite a feat for a novice quiltmaker due to the irregular shapes and figurative elements. Perhaps Thomas was part of the women’s group that presented Seay with a quilt that acknowledged the struggles Black federal workers in the Jim Crow South faced.16

Quiltmakers have long deemed their handiwork appropriate gifts to commemorate relationships and mark special occasions, including gratitude toward elected officials. Ordinary Americans sent thousands of gifts to Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt for their efforts at fighting the Depression and uplifting the national spirit. Among the items were many quilts, like the one the Romeo sisters, from California, sent in May 1933 to Eleanor Roosevelt, or the Blue Eagle National Recovery Act quilts that Ella Martin of West Virginia and Mrs. J. A. D. Robinson of Texas presented to the Roosevelts. Sometimes, women sent letters of gratitude, along with their quilts, to the presidential couple, thanking them for their support during those trying times.17

But the TVA quilts were more than expressions of gratitude; they were intended to persuade officials that the Black community living in the Tennessee Valley was worthy of the jobs, education, training, facilities, services, and electricity the TVA provided. Particularly for the quilts African American staffers presented to Morgan and Lilienthal—both men critiqued by the naacp for upholding the agency’s discriminatory policies—these objects were not gifts of gratitude but gifts intended to influence policy and practice, given the unequal conditions of Black life in the dam villages.18

What power can a quilt ultimately have? Ruth Bond wanted the quilts she designed to be objects for home beautification and statements about the positive effects of the TVA on African Americans and vice versa. She wanted members of the Black TVA community to feel pride in their work and pride in their heritage, despite the many challenges in their way. With scant documentation from the women who made the quilts, other than what they remembered decades later in oral history interviews, it is challenging to assess whether these quilts did in fact empower the Black communities associated with the TVA. Both Ruth Bond and Rose Thomas recalled these pieces as exemplars of their “Black Power” as a community, in the face of ongoing discrimination and limited opportunities. When interviewed in the late 1980s, Bond said of the Black Power quilt, “We were pushing up through obstacles—through objections. We were coming up out of the Depression, and we were going to live a better life through our efforts. The opposition wasn’t going to stop us.” Thomas similarly recalled in a late 1980s interview that “the women were excited about the new opportunities, and they wanted to show them in their quilt designs. . . . It is a hopeful message.” Was this message of empowerment and uplift heard by the white federal administrators? We only have Maurice Seay’s recollections of the gifted quilt from forty years later and the gratitude he presumed of the Black TVA families, which suggest more about aspirational social planning and its limitations. When we look at these quilts today, we continue to sense their power as artifacts. A group of women attempted to disrupt the customs and traditions of the rural South by crafting quilts with equally radical aesthetics and messages. In that sense, the quiltmakers achieved another outcome: a legacy of empowerment through craft.19

This essay first appeared in the Crafted Issue (vol. 28, no. 1: Spring 2022).

Janneken Smucker is professor of history at West Chester University. She serves as coeditor of the Oral History Review. Author of Amish Quilts: Crafting an American Icon (Johns Hopkins, 2013), Smucker lectures and writes about quilts for popular and academic audiences. This essay draws from her current project, A New Deal for Quilts.NOTES

- Max Bond, “Tennessee Valley Authority Office Memorandum,” November 1, 1934, personal collection of Merikay Waldvogel. Rather than use the period term, “Negro,” Southern Cultures replaces the outdated descriptor with terms in use today. Bond referred with pride to quilts and other crafts as “art of the Negro.”

- Merikay Waldvogel, Soft Covers for Hard Times: Quiltmaking and the Great Depression (Nashville, TN: Rutledge Hill, 1990), 78; Ruth Clement Bond, interview by Jewell Fenzi, November 12, 1992, Foreign Service Spouse Series, Foreign Affairs Oral History Program, Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training.

- It’s unclear who coined the names “Lazy Man” and “Uncle Sam’s Helping Hand” for the quilt. Ruth Clement Bond did not use “Lazy Man” in either her interview with Waldvogel or interview with Fenzi. Grace Tyler, one of the quiltmakers, did use this name in her interview with Waldvogel. When TVA purchased its quilt in this pattern made by Rose Lee Cooper, it named it “Uncle Sam’s Helping Hand.” In the summer of 2020, a previously unidentified version of the quilt given to TVA administrator Maurice Seay came up for public auction and is now in the collection of the High Museum of Art. Maurice F. Seay, “TVA Quilt Correspondence,” Quilt Index, September 10, 1976, https://quiltindex.org//view/?type=correspondence&kid=45-124-6. The location of the version Grace Tyler made, pictured in Waldvogel, Soft Covers for Hard Times, 79, is currently unknown. The TVA purchased another copy Rose Lee Cooper made. “The TVA Quilt,” Built for the People: Wheeler Dam, Tennessee Valley Authority, accessed September 3, 2020, https://www.tva.com/about-tva/our-history/built-for-the-people/the-tva-quilt. A fifth version is pictured in black and white in John P. Davis, “The Plight of the Negro in the Tennessee Valley,” Crisis, October 1935.

- Ruth E. Finley, Old Patchwork Quilts and the Women Who Made Them (Philadelphia; London: J. B. Lippincott, 1929); Lydia Le Baron Walker, “Revival of Old-Fashioned Thrift,” Evening Star, April 12, 1933; Marjorie Lawrence, “The Revival of an American Craft,” American Home, July 1929; “Here’s Thrift – Scottie Quilt in Easy Laura Wheeler Applique,” Daily Independent (Elizabeth City, NC), June 30, 1937. For more on governmental uses of quilts and quiltmaking during the New Deal, see Janneken Smucker, “A New Deal for Quilts – How the US Government and Depression Era Quiltmakers Pieced Together Their World,” 2021, https://newdealquilts.janneken.org/. For more on the colonial revival’s impact on quiltmaking during the Depression, see Waldvogel, Soft Covers for Hard Times, 2–23; and Shaw, American Quilts, 221–251.

- For more on the various ways the federal government used quilts in its New Deal programs, see Smucker, “A New Deal for Quilts.”

- Angelik Vizcarrondo-Laboy, “Fabric of Change: The Quilt Art of Ruth Clement Bond,” Museum of Arts and Design, February 22, 2017, https://madmuseum.org/views/fabric-change-quilt-artruth-clement-bond; Waldvogel, Soft Covers for Hard Times, 78; Bond, interview.

- “TVA Quilt.”

- Nancy L. Grant, TVA and Black Americans: Planning for the Status Quo (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990), 109; Bond, “Tennessee Valley Authority Office Memorandum,” November 1, 1934. For a detailed account of the ways Max Bond navigated his role at TVA, see Grant, 109–114. For more on Norris as a model community, see Charles Hamilton Houston and John P. Davis, “TVA: Lily White Construction,” Crisis, October 1934, 209–210, 311; and Tennessee Valley Authority, “Norris: An American Ideal,” accessed November 17, 2021, https://www.tva.com/about-tva/our-history/tva-heritage/norris-an-american-ideal.

- Cheryl Lynn Greenberg, To Ask for an Equal Chance: African Americans in the Great Depression (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2009), 52–53, ProQuest; Davis, “Plight of the Negro in the Tennessee Valley,” 294, 314, 315.

- Grant, TVA and Black Americans, 53. A harsh critique of the segregated living conditions for African Americans appears in Davis, “Plight of the Negro in the Tennessee Valley,” 295. Also see Steve Killingsworth, “Regional Planning on a Local Scale: The Brief Life of Pickwick Village,” West Tennessee Historical Society Papers 51 (January 1997): 54–55.

- Bond, interview; Merikay Waldvogel, “Regarding Quilts Made at Wheeler Dam Village (1930s),” undated, 9.1.b2.f38 Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) Quilts, WPA, Cuesta Benberry Papers, Michigan State University Museum.

- Waldvogel, Soft Covers for Hard Times, 82; Libbie Morrow, “Progress of Negro Race Told in Fisk Library Mural Decorations,” Nashville Banner, September 21, 1930; “Dr. Horace Bond, Educator, 68, Dies,” New York Times, December 22, 1972, https://www.nytimes.com/1972/12/22/archives/dr-horce-bond-educator-68-dies-led-social-research-unit-at-atlanta.html; Grant, TVA and Black Americans, 109; Davis, “Plight of the Negro in the Tennessee Valley,” 314. For discussion and images of Douglas’s Fisk murals, see Amy Helene Kirschke, “The Fisk Murals Revealed: Memories of Africa, Hope for the Future,” in Aaron Douglas: African American Modernist, ed. Susan Earle (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007), 115–135. Later in the 1930s, Horace Mann Bond directed Fisk’s Department of Education.

- Waldvogel, “Regarding Quilts Made at Wheeler Dam Village (1930s)”; Waldvogel, Soft Covers for Hard Times, 81; Grant, TVA and Black Americans, 42–44.

- Seay, “TVA Quilt Correspondence”; Waldvogel interviewed Rose Thomas for Soft Covers for Hard Times, 80; Ruth Bond quoted in Waldvogel, Soft Covers for Hard Times, 80–81. Seay recounted the gift in a document dated 1976, written upon loaning his quilt in the “Lazy Man” pattern to a folk art exhibit in Kalamazoo, Michigan. The document was published when the quilt came up for public auction in the summer of 2020.

- Davis, “Plight of the Negro in the Tennessee Valley,” 295; Russell Roberts, Pickwick People and TVA, 1935–1985 (Pickwick Dam, TN: R. R. Roberts, 1985), 53, 50; Killingsworth, “Regional Planning on a Local Scale,” 54–57.

- Waldvogel, Soft Covers for Hard Times, 79–80. The three small panels by Thomas are now in the collection of the Museum of Art and Design. Vizcarrondo-Laboy, “Fabric of Change.” The full-size quilt is in the collection of Michigan State University Museum. “TVA or ‘Lazy Man’ Quilt,” Trials, Triumphs, and Transformation | Middle Tennessee State University Digital Collections, accessed April 23, 2021, https://cdm15838.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15838coll7/id/205.

- For more on quilts given to or commemorating American presidents, see Sue Reich, Quilts Presidential and Patriotic (Atglen, PA: Schiffer, 2016). For an overview of quilts given to the Roosevelts, see Kyra E. Hicks, Franklin Roosevelt’s Postage Stamp Quilt: The Story of Estella Weaver Nukes’ Presidential Gift (Arlington, VA: Black Threads, 2012). For other examples of quilts given to FDR, see “Roosevelt Quilt,” Pasadena Post, May 22, 1933; “The N. R. A. Quilt,” Bluefield Daily Telegraph, May 10, 1936, http://www.newspapers.com/image/14974176; and “New Deal for Wintry Nights,” San Antonio Light, September 10, 1933.

- On critiques of the TVA’s racial practices and Morgan’s and Lilienthal’s perspectives on race, see Davis, “Plight of the Negro in the Tennessee Valley,” 314; and Grant, TVA and Black Americans, 33–35, 42–43.

- Ruth Bond quoted in Waldvogel, Soft Covers for Hard Times, 81; Rose Thomas quoted in Waldvogel, Soft Covers for Hard Times, 80.