I grew up in a house full of books, three of which belonged to my dad. They were his wellworn Bible; How I Made a Million Dollars in Mail Order, and You Can Too; and The Foxfire Book.

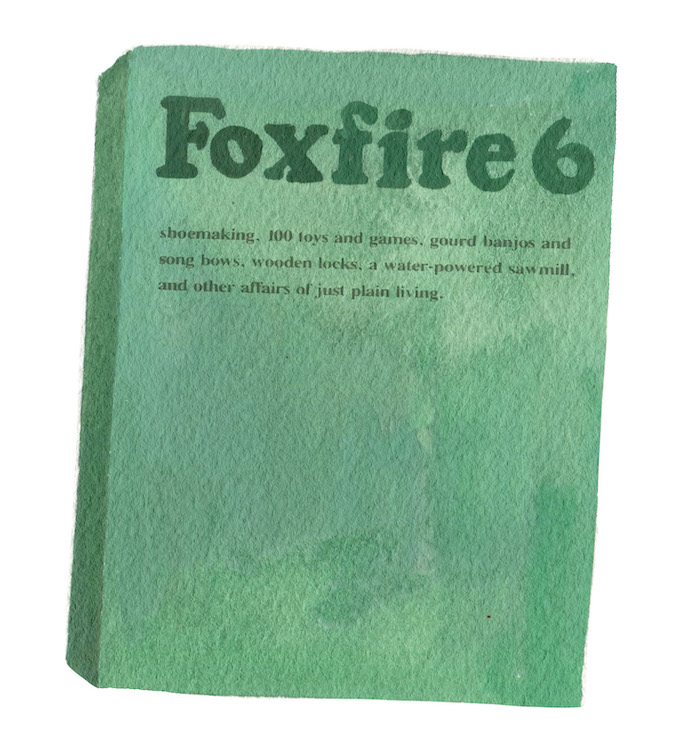

Published in 1972, The Foxfire Book carried the reader into the mountains of North Georgia, near the East Tennessee hills where my parents grew up and where I was raised. In 1966, thirty or so tenth-grade students from Rabun County, Georgia (population about eight thousand), set out to document the lives of elders in their community. They did so as part of a school project their teacher Eliot Wigginton started. He helped them edit and publish the interviews in the Foxfire Magazine, and it became a local hit. Wigginton had connections to a New York publishing house that found the project appealing and published The Foxfire Book, the first in a series of twelve that quickly became a bestseller, selling more than two million copies over a decade. It has also been adapted into a Broadway production and television movie.1

The book collated the articles from the student-run magazine, a literary project begun in 1966 following a discussion in Wigginton’s English class. The students voted to call the work “foxfire” after the bioluminescent fungi that grows on decaying trees and emits a blue-green light in the dark. Together, they decided that the magazine would focus on stories based on interviews with their grandparents and other elders in the community. Wigginton encouraged this approach because, as he wrote in the introduction of the first book, traditions practiced by older rural people—like planting by the signs—were soon to pass from collective memory. The students traveled to remote areas, carrying their notepads, microphones, cameras, and recorders. Their task was to document a skill or craft. While some students recorded the interviews, others joined in whatever skill was being demonstrated, like how to make soap or how to use a broad axe. Their project would illuminate rural Appalachian traditions and, as it expanded, augment the creation of a pioneer myth of Appalachia.2

Memorably, The Foxfire Book featured students conversing with Aunt Arie Carpenter, an eighty-four-year-old woman who lived alone in a cabin in the woods. Aunt Arie instructed her visitors how to clean the head of a hog. She explained, “Now see if you can take your fingers and pull that eyeball up and cut it.” Once the eyeball was free, she tossed it out the back door.3

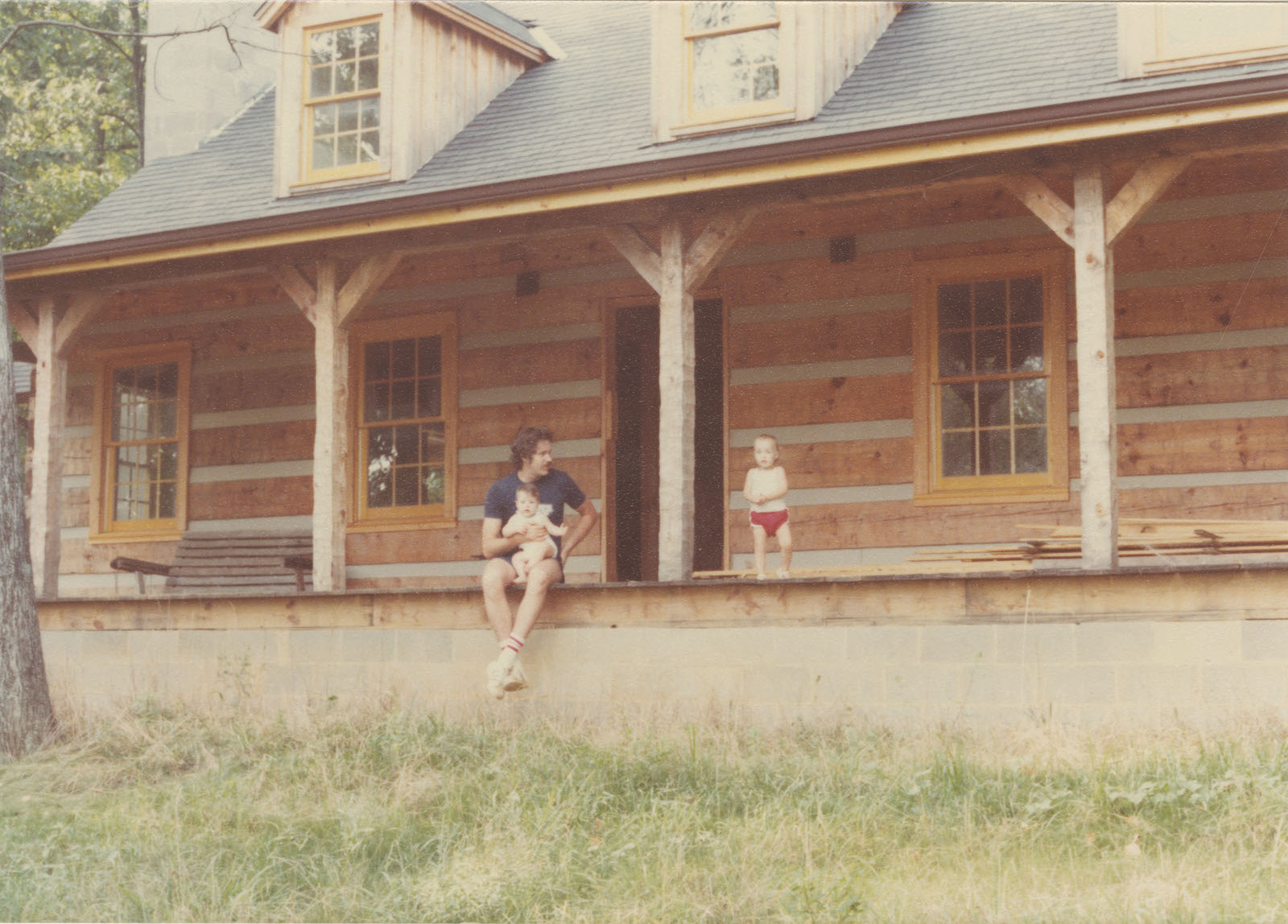

Other narrators tell us how to weave baskets, cane chairs, read nature, churn butter, and preserve vegetables. In the largest section of the book, local craftsmen provide step-by-step instructions on how to build a log cabin. That topic is why the book landed in my dad’s small collection. In the late 1970s, my parents decided to build a log house on my maternal grandparents’ land, which the family had farmed for several generations. In that era, there was a whole industry devoted to helping people build their own log homes, so my dad didn’t exactly need the instruction manual, but no doubt The Foxfire Book, gifted to him by a friend, gave him a sense of tradition. My parents cut down trees on the ridge where they would live, sparing as many dogwoods as possible so that their blossoms framed the house each spring. They sent the timber to a company that produced “log home kits” of hand-hewn logs. My dad built the house after work and on weekends over a couple of years. His father and brother pitched in when they could, and friends helped him when he needed to lift something heavy. My parents moved in right before Christmas 1982 with cast-off furniture from family members and two baby beds for me and my brother.

When you live in a log house, you’re close to the outdoors. I once got a two-inch long splinter stuck in my foot as I came running from my bedroom down the rough-cut log steps. Critters found their way inside, most often flying squirrels and bats. My mom would send us to my parents’ bedroom and let our cat Squeaky inside to catch the intruders. On top of a hill and surrounded by woods, the house encouraged one to commune with nature in ways that I imagined were unique to us, not the experience of my friends who lived in subdivisions a few miles away. During the summer, I fell asleep to the emphatic chanting calls of a whip-poor-will that sounded as though it was perched on my pillow, and the howls of dogs led me into dreams that featured packs of wolves.

I grew up in an invented Appalachia, of which Foxfire is part. I learned about an imagined Appalachia of independent and industrious mountaineers, a place of hardworking, rooted people in which my family felt pride. My grandmother took us regularly to the Museum of Appalachia in Norris, Tennessee. Founded by her cousin, the museum preserved the history of my family’s ancestors, white settlers who displaced Cherokee people in the Tennessee Valley in 1790. My grandmother was born near that first settlement and grew up on a farm there until the federal government’s Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) displaced her family and community in the 1930s to build the Norris Dam and flood the valley. This is how I learned about Appalachia: it was something in the past, something that could disappear if we did not put effort into preserving what was left of the story. It was old ways and old times, rarely about our contemporary lives.4

In our log home, I was surrounded by the stuff upon which people once relied for living. My mom collected artifacts to decorate the house—quilts that my great-grandmother sewed with her female kin; my Granny Clapp’s egg basket; an old butter churn. Although I paid little attention to these objects when I was growing up, their existence meant that the names of ancestors, and sometimes their stories, were part of my family’s collective memory. My grandmother and great aunt would pull out old quilts form the chest, unfold them, and trace their fingers over the names embroidered on squares, recalling people and times past—including the women who had sat and quilted together. I now keep some of the objects in my own home. But I realize that these anchors to the past, unmoored from people and place, could just as easily become traps of nostalgia or commodities.

We can’t really understand The Foxfire Book without understanding the world that produced it. The Foxfire Book is an artifact of a particular time and place, and like any other artifact it tells multiple and conflicting stories all at once. It beckons us to read its pages as authentic, unfiltered renderings of everyday Appalachian living. In fact, its contents—instructions in how to live a semisubsistence lifestyle—were becoming ever more extraordinary by the time it was published in 1972. The gap between young and old is evident, for instance, in the story of how the Foxfire crew came to be introduced to Aunt Arie. A student named Patsy told Eliot Wigginton in the early years of the project: “You know, since you’re interested in old people, and what they used to do around here, you might be interested in my great aunt. She still lives in a log house and does a lot of that old stuff.”5

This is our point of departure. We know who wrote the book, who the authors interviewed, but that’s merely a fraction of the story. The Foxfire Book communicates ideas about real people’s lives while also selling an imagined Appalachia, and it emerged from relationships that were both life-giving and destructive.

Rabun County, Georgia, where Foxfire originated, is a place of lush landscapes and breathtaking beauty. The Chattooga River forms the eastern border, and the Blue Ridge Mountains rise up in the west. For thousands of years, it was the ancestral land of the Cherokee people. Following a treaty in 1819, the United States forced the Cherokee Nation to give up four million acres that encompassed what would become Rabun County, and in the 1820s and ’30s, white settlers rushed into the territory searching for gold. They found some but more so fertile land, which they claimed as their own, forcing the Cherokees out. Many settlers eventually started farms, and some of them brought enslaved men and women with them. Following the Civil War, the first railroad reached the county, and two industries emerged: logging and tourism.6

In the early twentieth century, the federal government began to enclose and regulate the commons—or the forests from which people freely took materials and sustenance. The Forest Service bought huge tracts of land, pushing farmers out of the area; limited the numbers of cattle that farmers could graze; and decided who could log and when, giving preference to large companies. Georgia Railway and Power Company dammed the Tallulah River, destroying the Talullah Falls, known as the “Niagara Falls of the South.” The dam generated hydroelectric power, with the vast majority of kilowatts sent to Atlanta to power the New South city. Many residents gave up farms for wage work in the textile mills that sprouted up in northern Georgia and throughout the North and South Carolina Piedmont. By the 1950s, textile mills had opened in Rabun County, as well. The parents of the children who collected the Foxfire stories probably worked in factories or in the service industry, which catered to tourists visiting the area’s national parks, forests, and lakes. This was their Appalachia. In the rapidly modernizing postwar world of industrial work and store-bought goods, few people required the skills of the past. Canning, preserving, sewing quilts, gathering herbs and nuts, weaving baskets, curing hog meat—what once had been common practice began to fade from living memory.7

As the students interviewed elders, they formed and strengthened a shared connection to a fraught geographical place—Appalachia and, more specifically, the Blue Ridge Mountains that straddle the boundaries of North Georgia and Western North Carolina. The students of Foxfire set out to document the daily activities of their aging kin and neighbors before the knowledge they possessed disappeared. We can only dimly imagine what happened in the space of those interviews when adolescent youth sat with elderly women and men and asked them about their lives. What happens when that very intimate practice of sitting with and listening to a person becomes unmoored from place?

Foxfire‘s positive portrayal of people who lived in the Georgia mountains countered the grossest, most negative stereotypes, also sold to the masses in the same era, principal, perhaps, the 1972 blockbuster film Deliverance. James Dickey, author of the best-selling 1970 novel of the same title, claimed to depict the place and people of Rabun County. Deliverance told the story of four businessmen from the suburbs who head to the mountains for a weekend of adventure. They face instead what literary scholar Emily Satterwhite describes as “an Appalachia that served as the site of a collective ‘nightmare.’” The plot revolves around the rape of one of the men by a reprehensible hillbilly, and it follows that the narrator must avenge his friend’s rape, prove his masculinity, and conquer the untamed wilderness.8

Through Foxfire, the real-life youth of Rabun County responded with stories of smart, witty, industrious people. They refused stories that claimed people in Appalachia were naturally violent and products of a culture of poverty. Foxfire emerged at a moment when the predominant images of the region were filtered through black-and-white photography that portrayed people as “white, deprived, and spiritless.” In the late 1960s and 1970s, many young people in Appalachia participated in new cultural movements to define Appalachia on their own terms, creating new media outlets and documenting in greater complexity the lives of people who lived in their communities.9

The idea of Appalachia communicated in Foxfire had the capacity to counter the harmful portrayals in media like Deliverance, but it also functioned in potentially more sinister ways within a broader political landscape, what historian Matthew Frye Jacobson has called the “evasions of whiteness.” The adult editors (all of them very likely white) demonstrated for the students an imagined past. Not unlike some of the most popular books on Appalachia then and now, Wigginton, the editor of the books, mourned that industriousness and hard work was on the wane. To study and preserve traditions of rural white people was good not just for the sake of history, but because that history contained lessons for people in the present. In such a rendering, the elders of Foxfire look more like mythic pioneers than 1970s Americans amid social upheavals, and we learn that those pioneers were consistently wholesome, good, and self-reliant. Foxfiresold a white ethnic identity that separated white Appalachians from skin privilege and the centuries-long history of American racism and domination, under renewed scrutiny in the crucible of the Black freedom struggle and 1970s liberation movements. While the early Foxfire books include an occasional story about a Black or Indigenous person, the story of white pioneer history remains intact. The presence of Black and Indigenous historical actors function as well to emphasize a parallel white ethnic identity of Appalachians.In countering Deliverance, the Foxfire project offered another form of deliverance.10

But in avoiding a complex and less-than-celebratory history, the books contributed to the history of settler colonialism in the nineteenth century, the violent clash as white settlers stole land from Indigenous people. We hear nothing of the six racial terror lynchings that occurred in the neighboring county or the dozens of others in North Georgia. We fail to learn how the Appalachian South came to be dominated by and identified with white people. The Foxfire project is largely silent on how midtwentieth-century liberation movements touched and transformed Appalachia. To sidestep those fuller stories, and to fail to account for past and ongoing harms, cuts short possibilities of building solidarity with oppressed people, one staked on a “sense of belonging” as described by Black feminist bell hooks in her poetry collection Appalachian Elegy. When detached from a complex past, Foxfire contributes to the construction of an imagined and static white Appalachia.11

What happens when highly constructed tales of Appalachia become a portal for voyeurs who want to cling to idealized American spaces? Something similar occurred in the early twentieth century, when white social reformers saw in Appalachia a preserve of Anglo-Saxon tradition, a keystone in the creation of new forms of white supremacist ideology. We might also ask how and why Appalachian food and culture become novelties today. How do we get from Aunt Arie living on her plot of land, preparing a hog’s head and declaring her love of jowl meat, to my eating a $25 plate of hog jowls for the first time at a white table cloth restaurant in Oxford, Mississippi? (I loved them.) The stories in the Foxfire books, facsimiles of exchanges between old and young people in very specific places in Rabun County and surrounding areas, become something else when bound and sold as an authentic Appalachian experience. Capitalism distorts the archive of stories. As Appalachian studies scholar Erica Abrams Locklear explains, we risk dulling “the edge of complex food stories” when once-derided foods—in particular, those eaten by poor and rural people—become venerated. And when people sell and consume ideas of white Appalachia, for ideological reasons or for profit, I must wonder where that gets people who actually live in Appalachia.12

Artifacts—including books—tell us about social relations. They tell us about class, race, gender, sexuality, and power, who has it and who does not. Power often silences the less powerful. In our reading, we can explore the unstated, as well as the unspeakable.

The world of the Foxfire elders was becoming ever more distant when the youth set out to interview them. The elders understood a different kind of economy, no doubt imperfect, and possible only through settler colonialism—the process by which European and American settlers sought to overcome the obstacle of Indian claims to land, through wars, disease, dispossession, and legal maneuvers. Nonetheless, it was an economy in which households could sustain themselves without the aid of capital. When the Foxfire narrators instruct on how to grow and preserve food, we can hear lessons also about the necessary buffers to the horrors of industrial and environmental destruction that so frequently shook Appalachia in the twentieth century. We can imagine the stories of striking workers, who shared food and squared off against capital for another day, such as when textile workers in North Georgia joined the Great Textile Strike of 1934. In the celebrations of women’s vital labor, I also hear the churning of twentieth-century markets. Industrial capitalism relied upon women’s unpaid labor—gardening, cooking, sewing, managing households, and taking care of children and the elderly—while making that labor more difficult to perform.

The Foxfire stories are artifacts of capitalism that, as historian Steven Stoll argues, “increased in cultural value as industrial capitalism undermined their environmental and social basis.” Curing hog meat becomes a revered skill in the culture only once ham is readily available at the supermarket. Curing hog meat—and all manner of food production—symbolizes what was lost in a transitioning economy. But it wasn’t just the skills, according to Foxfire. It was a way of being. Foxfire purports to educate on how to live plain and to be independent, like those hardy ancestors. Yet, as the young interviewers gathered stories, another form of capitalism was taking shape, one that would dismantle the textile manufacturing base of their community. The mothers and fathers of those Foxfire students would work harder for less pay in the decades to come. I imagine they would look upon the work of their children with pride but also worry about their future, not because their children lacked traditional skills, but because the future is always dark. Try as we might, we cannot fathom what skills the next generation will need to cope.13

These worries about capitalism’s ravages were not the only ones concerning power and exploitation, however. Eliot Wigginton—the Cornell-educated teacher who started the Foxfire educational program, edited its volumes, was named Georgia “Teacher of the Year,” won a MacArthur grant, and lambasted James Dickey’s dark and sexually violent portrayal of Appalachia—is alleged to have sexually abused at least twenty boys in his charge. The first reports came forward in 1986, although police dropped investigations. In 1992, a ten-year-old boy told his parents what his teacher had done to him. Wigginton denied the charges, but one by one Foxfire alumni came forward, defended the boy, and told their own stories of shame, denial, and survival. Wigginton then pled guilty to one charge of child molestation and spent one year in jail and nineteen years on probation as a registered sex offender in Florida, where he lives. This, too, is a Foxfire story.14

Young Appalachians preserved the stories of elders and made those connections to their community in spite of the teacher who abused and ultimately silenced them, while claiming to bring salvation to this Appalachian hamlet. He chided those who caricatured the region at the same time he manipulated and abused its citizens. In retrospectives, writers and researchers tell us that despite Wigginton’s downfall, he gave Rabun County a reason to feel pride and paved the way for students to recognize what was important in their own community. There is no doubt a seed of truth in this telling, and it makes it all the more painful. But I refuse a story that implies, as some do, that we simply must take the good with the bad. To gloss over Wigginton’s violent exploits, to describe them as an isolated “dark period” in Foxfire’s history, is to fail to consider how others were implicated in, and how our society creates the conditions for, abuse.It renders Wigginton’s victims a necessary sacrifice. And it cuts off the possibility of imagining how to repair decades of harm and coming to terms with how a program that celebrated Appalachian traditions also created conditions to perpetuate violence.15

In his own writing and in that of others, Wigginton is rendered as a central figure, a charismatic teacher willing to buck tradition and inspire his students, revealing to them the beauty of their own culture, invisible to them before his leadership. Therein lies a profound deception. The truth is Foxfire could never have existed without the students’ labor and vision, without their relationships with grandparents, their neighbors, and the elderly women and men who lived by the rules of a makeshift economy.

Perhaps the best of the Foxfire program—the truest and most admirable of the Foxfire stories—emerged in the relationships between students across time and space. As Wigginton denied allegations of abuse and the organization was slow to respond, adult alumni garnered the courage to defend one another and the most recent victim and to tell the truth, despite the risks it posed to the organization. Because of students and their commitments to one another, the program has continued to inform and inspire thirty years after Wigginton’s downfall.16

The Foxfire students and writers saw and heard people without fetishizing them, even if their audience often did. In that first story about Aunt Arie, student interviewer Paul Gillespie informs the reader: “She was proud of what she had done and what she had accomplished, but there was no need in her mind to try to make me feel that I should be in awe of what she said.” Hers was a life and experience that he respected and valued. Paul Gillespie and his fellow interviewers preserved stories of elders because they were real people and honored members of their community. These were the stories they knew and valued, the histories they shared, the humanity they recognized, only a fraction of which we are privy to.17

I love the house my dad built for my family and the things that fill it. And I value many of the Foxfire stories. I do so not because they transport me back in time, or for what they teach me about pioneer skills or, even, Appalachia, but for the mystery that they often inspired in me, the expansive backdrop of narrative interpretations they offered. I imagine my father alone on a hillside, at work on a house on cold winter nights, preparing for a future with his wife and two babies, another soon on the way. I wonder about the people who warmed up and dreamed under scraps turned into beautiful quilts that sit in my cedar chest more than a century later. At the same time, I recognize that objects threaten, as Virginia Woolf once wrote, to “enforce the memories of our own experience.” Even more so when we encase those things with uncomplicated histories, drained of the uncertain and fraught human relationships that gave rise to them in the first place. That’s why it’s so important that the Foxfire students interviewed elders; in listening to them, they formed new bonds, and they resisted oppressive political narratives in their present. In hearing all those voices, they refused a single story of Appalachia—be it the nightmare of Deliverance or the idealized rendering curated by Wigginton. Storytelling is, as scholar Della Pollock explains, an “action on and in the particular world that bore” the stories; to tell stories is to participate in the “continual re-creation of the world.” When students in Rabun County created the conditions for storytelling, others’ and their own—something that could never be rendered easily on the page—they gained a little more room to imagine their own futures, of their own making.18

This essay first appeared in the Crafted Issue (vol. 28, no. 1: Spring 2022).

Jessica Wilkerson is the Stuart and Joyce Robbins Associate Professor of History at West Virginia University. She is the author of To Live Here, You Have to Fight: How Women Led Appalachian Movements for Social Justice (University of Illinois Press, 2019).NOTES

- Adrienn Mendonca, “Foxfire,” New Georgia Encyclopedia, last modified November 2, 2015, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/education/foxfire/.

- Eliot Wigginton, The Foxfire Book (New York: Anchor Books, 1972), 9–14.

- Wigginton, The Foxfire Book, 20.

- On archetypal images of Appalachia and their political purposes, see Allen W. Batteau, The Invention of Appalachia (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1990), 10–18, 190–193.

- Linda Garland Page and Eliot Wigginton, eds., Aunt Arie: A Foxfire Portrait (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992), xii.

- On the history of the Cherokee Nation, treaties, and white settlement in North Georgia, see Tiya Miles, Ties that Bind: The Story of an Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and Freedom (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2006). On the history of Rabun County, see Richard Cinquina, “Rabun County: The First 200 Years,” Rabun County Historical Society, accessed November 30, 2021, https://rabunhistory.org/articles/rabun-county-the-first-200-years/.

- Cinquina, “Rabun County”; Andrew McCallister, “Tallulah Falls and Gorge,” New Georgia Encyclopedia, last modified November 2, 2018, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/geography-environment/tallulah-falls-and-gorge/. Foxfire texts published over the years reference memory of past traditions and lifestyles as under constant threat of fading and being forgotten in a modern world. For example, see Joyce Green, Casi Best, and Foxfire Students, eds., Singin’, Praisin’, Raisin’:The Foxfire 45th Anniversary Book (New York: Anchor Books, 2011), xix.

- Emily Satterwhite, Dear Appalachia: Readers, Identity, and Popular Culture Since 1878 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2011), 149.

- Elizabeth Catte, “Passive, Poor, and White? What People Keep Getting Wrong about Appalachia,” Guardian, February 6, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/feb/06/what-youregetting-wrong-about-appalachia; Jessica Wilkerson, “The Appalachian Presence in the Poor People’s Campaign,” Rewire News, June 21, 2018, https://rewirenewsgroup.com/article/2018/06/21/appalachian-presence-poor-peoples-campaign/; Edward D. Smith, Black Power Comes to Appalachia: Bereans Create the Black Appalachian Commission, A Documentary History, 1969–1970 (self-pub., 2019); “Appalshop 50,” accessed November 30, 2021, https://appalshop.org/story.

- Matthew Frye Jacobsen, Roots Too: White Ethnic Revival in Post-Civil Rights America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), 2. On Appalachian identity politics, see Batteau, Invention of Appalachia, 186–189.

- “Lynching in America,” Equal Justice Initiative, accessed November 30, 2021, https://lynchinginamerica.eji.org/explore/georgia; William Fitzhugh Brundage, Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 1880–1930 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993); bell hooks, Appalachian Elegy: Poetry and Place (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2021), 4.

- Erica Abrams Locklear, “Setting Tobacco, Banquet-Style,” in The Food We Eat, The Stories We Tell: Contemporary Appalachian Tables, ed. Elizabeth S. D. Engelhardt and Lora E. Smith (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2019), 36.

- Steven Stoll, Ramp Hollow: The Ordeal of Appalachia (New York: Hill and Wang, 2017), 242.

- Debra Viadero, “Fall from Grace,” EducationWeek, January 1, 1994, https://www.edweek.org/education/fall-from-grace/1994/01; Ronald Smothers, “‘Foxfire Book’ Teacher Admits Molestation,” New York Times, November 13, 1992; Steve Walburn, “Sometimes a Shining Lie,” Atlanta Magazine, accessed November 30, 2021, https://stevewalburn.com/sometimes-a-shining-lie/.

- Charles Bethea, “Where Foxfire Still Grows,” Youth Today, December 28, 2021, https://youthtoday.org/2012/12/where-foxfire-still-glows/; J. Cynthia McDermott and Hilton Smith, “Eliot Wigginton—No Inert Ideas Allowed Here,” Sourcebook of Experiential Education: Key Thinkers and Their Contributions, ed. Thomas E. Smith and Clifford E. Knapp (London: Taylor and Francis Group, 2010), 262–271; Tove Danovich, “The Foxfire Book Series That Preserved Appalachian Foodways,” NPR, March 17, 2017, https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/03/17/520038859/the-foxfire-book-series-that-preserved-appalachian-foodways; Mariam Kaba, We Do This ‘Til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transforming Justice (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2021), 197–296.

- Viadero, “Fall from Grace.”

- Wigginton, The Foxfire Book, 20.

- Virginia Woolf, “Street Haunting: A London Adventure” (London: Symonds, 2013); Della Pollock, “Telling the Told: Performing Like a Family,” Oral History Review 13 no. 2 (Fall 1990): 1–36, 5, 10.