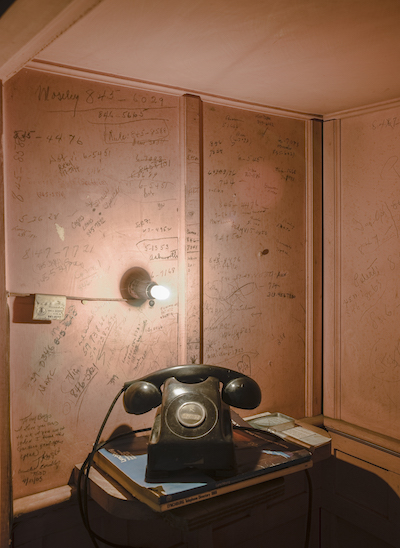

Poet, librarian, and activist Anne Spencer was the first African American woman to be featured in the Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry. Much of her poetry focuses on her beloved home and garden. Tended for over fifty years and lovingly restored after her death, the garden is described in one poem as “half of my world” and is now maintained with support from the Garden Club of Virginia. In his biography of the poet, J. Lee Greene writes that when Spencer walked through her home, she would often “recall a person, an incident, a memory, an object that . . . made the room and space seem sacred to her.” These sacred spaces were a refuge from the Jim Crow South, where the Spencers celebrated beauty and hosted a remarkable collection of guests. She once noted, “We have a lovely home—one that money did not buy—it was born and evolved slowly out of our passionate, poverty-stricken agony to own our own home.”

Few people know that the Harlem Renaissance had a vibrant outpost in the South, but Anne and Edward Spencer’s Lynchburg, Virginia home became a frequent stop for Black scholars and artists as they traveled up and down the East Coast. Due in part to Spencer’s poetry and the force of her personality, the home became a salon of sorts, a protectorate in the South of the cultural, political, and social advancements slowly being made across the country. Among their visitors and overnight guests were Gwendolyn Brooks, George Washington Carver, Countee Cullen, W.E.B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes, Mary McLeod Bethune, James Weldon Johnson, Martin Luther King Jr., Thurgood Marshall, Marian Anderson, Adam Clayton Powell Jr., and Paul Robeson. The home represents civil rights history, the founding of the NAACP, a rich vein of African American literature, and the hard-fought gains of America’s Black middle class.

About her poetry, Spencer said, “I write about some of the things I love. But I have no civilized articulation for the things I hate.” It wasn’t only racism that she hated but any kind of discrimination—against people of color, women, or the poor. From 1923 to 1945, Spencer served as the first librarian at Lynchburg’s all-Black Dunbar High School. During this period, she helped establish the local chapter of the NAACP, led a campaign to hire Black teachers, and served on various committees to advocate for racial justice.

I write about some of the things I love. But I have no civilized articulation for the things I hate.

As an assistant librarian in UNC’s Couch Botanical Library, I first became aware of Anne Spencer in 1987, when American Horticulturist published an article about the restoration of her garden. A poet and gardener myself, I was intrigued to learn about another poet’s garden and hoped to visit it someday. The Spencer home is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and has been designated a Virginia Historic Landmark. In 2012, my friend John Hall arrived in Chapel Hill with a portfolio of photographs after visiting Lynchburg to meet Shaun Spencer-Hester, Anne’s granddaughter, who now curates the House and Garden Museum. John has a long and distinguished career as a photographer of interiors and gardens, and his photographs here, so richly evocative of Anne and Edward’s vision, and of Shaun’s equally resourceful guardianship of her family’s legacy, are a door into a vivid world like no other.

John M. Hall grew up in rural North Carolina and was educated at North Carolina State University and the North Carolina School of the Arts. A scholarship to American Ballet Theater brought him to New York City, where he trained and performed in ballet and worked for architect Paul Rudolph before moving to Europe, where he worked as a fashion model and first developed an interest in photography. His fascination with the visual world and facility with the camera led to a wide-ranging career as a photographer of architecture, interior décor, and gardens for magazines, newspapers, architects, and private clients. He is the author of numerous books on photography and architecture and his photography has been featured in the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Architectural Digest, Elle Décor, Veranda, and other leading publications. His fine art photographs are represented in museums as well as private and corporate collections, and are exhibited frequently.

Retired UNC botanical librarian Jeffery Beam‘s works include The Broken Flower, Gospel Earth, Visions of Dame Kind, An Elizabethan Bestiary, The New Beautiful Tendons, Jonathan Williams: Lord of Orchards, and Spectral Pegasus, the latter a collaboration with painter Clive Hicks-Jenkins. His song-cycle The Life of the Bee (composed by Lee Hoiby) premiered at Carnegie Hall and can be heard on New Growth along with Beam reading. Steven Serpa also continues to compose with his poems.