Zora Neale Hurston, Margaret Walker, Flannery O’Connor, Beth Henley, Alice Walker, Mary Karr, Jesmyn Ward. Women writers in every generation have left southern states in search of opportunities and in defiance of racial, economic, sexual, and gender-based oppression. Within the decades-long Great Migration of African Americans out of the region (and now back into it), there is a less storied tradition of women joining the “southern diaspora.” In the wake of the Civil Rights and Women’s Liberation Movements, many southern women writers left the South to escape its intersectional injuries, and even more recently, some writers have returned. These literal and literary migrations have enabled women writers to address regional inequities in their texts and, for those who return, in their southern communities. Leaving, for some, has been the price of their work; returning, for others, is a personal and political act that has become a part of their writing and a means for understanding the region, their concepts of home, and themselves.1

While women writers have been leaving the South for generations, this journey became an explicit subject of examination in the early 1980s. A manifesto of the out-migration came in 1982, in the final issue of Feminary, a North Carolina feminist journal, which was dedicated to “The South as Home: Staying or Leaving.” Feminary was a major voice for southern queer women who, instead of fleeing repression, chose to stay “to work in our home for more inclusive and just cultures,” in the words of one of the journal’s founders. The contributors to “Staying or Leaving” describe the various forms of discrimination faced by women in the region, elucidating the patriarchal abuses of the rigid sociocultural system that punished women based on sexual orientation, sexual identity, race, and class. “The South is our home,” mused a longtime editor in the introduction to the issue. “What about all of the other women, women who are here, women who have left, and women who have returned?” The contributors offered some answers to this question. One anonymous essayist wrote simply, “By the third grade, I knew I would have to leave. I was too queer to stay.” Anita Cornwell, a Black lesbian author and activist, wrote of experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder as she and family members drove across rural South Carolina. Thinking of her ancestors, she wondered if she and her companions would make it across “this rebel land” alive. Cornwell was not alone in suffering from these historical terrors. Most of the members of the Feminary publishing collective left the South soon after the issue was published, as did Feminary itself, which moved to San Francisco under a new group of editors shortly thereafter. Despite the ambivalence of a few of the contributors, the answer to the question of “staying or leaving” seemed overwhelmingly to be the latter.2

The authors and activists of Feminary were representative of other homegrown writers wrestling with the region. The year after the journal relocated from the South, Alice Walker published her influential essay collection In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens (1983), in which geographical ambivalence was a major theme. Growing up in Georgia, Walker knew that she “would have to leave all this. Take my memories and run north.” Like her muse Zora Neale Hurston, Walker left for school elsewhere, just as, “one by one,” her seven brothers and sisters before her had left the South. “Abandonment, except for memories,” was the usual course for those who had the means, however meager, to get away, and Black writers were no exception. Despite the rural South’s “enormous richness and beauty,” which offered a natural gift to regional writers, Walker observed that “Black writers had generally left the South as soon as possible.” Other writers did not have the benefit of experiencing “the magnificent quiet of a summer day when the heat is intense and one is so very thirsty, as one moves across the dusty cotton fields, that one learns forever that water is the essence of all life.” The humidity, the rain, the very dirt of the South were precious to Walker and to her writing.3

This love meant that, like Hurston, Walker “left the South only to return to look at it again.” Although she had the opportunity to go abroad on a scholarship, she was inspired by Dr. King’s entreaty to “go back to the South,” even though, she wrote, “no black person I knew had ever encouraged anybody to ‘Go back to Mississippi.’” Reversing the usual trajectory, Walker went even deeper into the South beyond her native Georgia, to Jackson, Mississippi, resolving that “in order to be able to live at all in America I must be unafraid to live anywhere in it.” While there, one of Walker’s missions was to investigate Black women writers. “The past,” she explained, “is studded with sisters who, in their time, shone like gold,” women that the poet Jean Toomer, a favorite of Walker’s, saw as “exquisite butterflies trapped in an evil honey.” Along with working for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and the Head Start Program, Walker’s resurrection of southern Black female writers was crucial to her mission in the South.4

“In order to be able to live at all in America I must be unafraid to live anywhere in it.”

Like all activists in the Civil Rights Movement, Walker bore her share of physical and psychological traumas. Future generations, she believed, would enjoy life in the Deep South as a “natural right,” but, for her generation, memories “sour[ed] the sweetness of what has been accomplished in the South.” She and her siblings purchased the woods around her mother’s birthplace, a hopeful gesture that echoed the trickling in-migration of Black Americans to the South in the 1970s, signs of the coming reversal of the Great Migration. Bucking this trend, Walker moved out of the South in the early 1970s, claiming she had “freed” herself to go.5

Yet Walker continued to return, not just to visit her family but to fulfill her mission of reclamation. In 1974, Walker journeyed to Georgia to visit her childhood home and the final home of one of her favorite white southern writers, Flannery O’Connor, both of which were just outside of Milledgeville, Georgia. In search of their old tenant house, Walker and her mother came upon a familiar barn, where they saw that her mother’s daffodils had multiplied over the years to cover the entire yard. The abandoned bulbs were in full bloom in front of the ruined remains of their old house. “The only pleasant thing,” Walker recalled, was a bucolic field nearby, and as they drove away in search of O’Connor’s farm, she realized that it was, in fact, “Flannery’s field.” Like Walker, O’Connor left the South to be a writer in New York, but illness forced her return. Back home in Georgia, she wrote much of her best-known work in the house that Walker and her mother visited. It was large, white, and “neatly kept,” gleaming on a hill overlooking a lake; peacocks milled around the yard, and in the back, there was a “shabbier” house for “the help,” “within calling distance from the back door.” Walker considered how the antebellum homes in the South were built by forced labor, wondering if perhaps O’Connor’s childhood home in Milledgeville had been constructed by some of her own enslaved ancestors.6

As she stood in front of the house in which O’Connor spent the end of her life, Walker compared it to the ruins of her own former home. O’Connor returned to her antebellum house, a former cotton plantation, to produce the work that earned her respect as one of the South’s foremost writers. Walker, on her mission of reclamation, recognized this disparity not only as one of racial and class privilege but also of geographical barriers. Her former home was not a site of longevity and productivity but a decrepit shack that she had to leave to write much of the southern fiction for which she would be known. Standing there with her mother, Walker thought about how William Faulkner’s house in Mississippi was well-maintained by a “Black caretaker,” while no one seemed to remember where Richard Wright lived, and she began to feel “Faulkner’s house, O’Connor’s house, crushing” her.7

As Walker and her mother returned to their car to leave O’Connor’s house, one of the peacocks spread his tail, temporarily blocking their exit. Walker admired him, but her mother warned that peacocks “will eat up every bloom you have, if you don’t watch out,” a dual metaphor for the exploitation of Black women’s creative labor and for the white supremacist canonical system that recognized O’Connor as a major southern author, while Zora Neale Hurston’s overgrown grave would have continued to languish had Walker not tracked it down and marked it herself. The beautiful but threatening peacocks, and her mother’s abandoned but flourishing flowers, made Walker’s process of reclamation a crucial part of her work.8

Just as leaving the South was about more than opportunity, Walker’s visits were about more than family and roots. Over lunch on the visit to their former home and O’Connor’s farm, Walker’s mother asked her why she came back to the South: “Just what is it exactly that you’re looking for?” Walker replied that she was looking for “a wholeness,” and that these visits were in some ways a pilgrimage: “I believe that the truth about any subject only comes when all the sides of the story are put together, and all their different meanings make one new one. Each writer writes the missing parts to the other writer’s story. And the whole story is what I’m after.” And yet the whole story rarely came to Walker in the South. To write about it—and to write about it very successfully, to the tune of a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award—she needed to be away, first in New York, then in San Francisco, and ultimately in rural Northern California, where, finally, Celie, the heroine of The Color Purple, “began haltingly, to speak.” “And no wonder,” Walker later explained: the land where she settled in to write the novel “looked a lot like the town in Georgia most of [her characters] were from,” where in fact Walker was from, “only it was more beautiful and the local swimming hole was not segregated.” Walker’s best writing about the South, that “beloved but brutal place,” blossomed while she was away. Since then, she has lived in many places, including Hawaii and Mexico, and Walker connects this movement, this leaving, to historical experiences in the South: “It’s as if I got all of this energy from ancestors who were not permitted to leave the plantations for 400 years and I got all of their desire to be part of the world.” Leaving, then, was a reparative prerequisite for Walker and her writing, as was the ability to return, reclaim, and leave again at will.9

The same year that Walker wrote of leaving and returning to the South, Shirley Abbott published her meditation on growing up in the region, Womenfolks (1983). Abbott saw herself as “part of a vast northward exodus,” one of the “quota of travelin’ women” who did the math on “the high cost of living and dying in Dixie” and fled. This flight had “special meanings for women,” who left a “past rooted back in the hard earth” and in the intolerable regional mythologies of gender, sex, and race. While historians of this era were writing more scholarly critiques of the so-called southern lady, Abbott’s recounting of her struggles with the prescriptions of white southern womanhood was personal and evocative, and it left enough of an impression on the young writer Dorothy Allison that a copy of Abbott’s chapter “Why Southern Women Leave Home,” reprinted in the Boston Review, can be found in Allison’s papers and personal correspondence in the archives at Duke University. In the early 1980s, Allison, an expatriate South Carolinian, was a struggling graduate student and poet in New York, and a primary question in her work centered on the tensions of leaving. She later called this “the geographic solution,” one which her poverty-stricken family had tried when she was thirteen, running from South Carolina to Florida to avoid debt. Self-described “trash,” Allison endured the regional caste system as well as intensely violent encounters with southern patriarchy in the form of her abusive stepfather. The “geographic solution” saved her life and enabled her career as an author. She explained:

I wanted to start over completely. . . . I wanted to run away from who we had been seen to be, who we had been. . . . It’s the first thing I think of when trouble comes. . . . What hides behind that impulse is the conviction that the life you have lived, the person you are, is valueless, better off abandoned, that running away is easier than trying to change things, that change itself is not possible.10

Yet, for Allison, once she got away, change was possible. She left the South for many reasons: to pursue a master’s degree in anthropology, to escape from her violent stepfather, to explore her sexuality, to develop the feminism she had discovered in a Tallahassee consciousness-raising group. Allison joined existing feminist organizations and helped to form new ones, including an epistolary community of southern women expats. While she maintained these literary connections to home, the seven-hundred-plus miles between her hometown of Greenville, South Carolina, and New York City offered Allison enough distance to take a hard look backward and to write about not just her own experiences, but also those of the paradoxically powerful and abused women in her family.11

“Having those wrapped packages in the freezer reassures me almost as much as money in the bank.”

Allison rarely visited her family in the South, despite her beloved mama’s “completely obsessive need” for her to do so, because being around her abusive stepfather made her physically ill. But she could no more escape the South than she could forget the trauma, and her complicated relationship with her history played out in the most tangible of ways. Emotional hunger is a frequent theme in her writing, and it’s one she connects to the physical hunger of growing up poor in the South. In New York, she wrote, she dreamed of homemade biscuits, of beans cooked with pork fat and onions, of all kinds of greens, which she searched for in cramped urban bodegas. Trying to recreate southern food became a means of keeping the demons at bay, of sustaining her troubled connection to the South from which she had run. In “A Lesbian Appetite,” she writes of waking up “desperate for the taste of greens,” searching for an open deli in the middle of the night “that still has a can of spinach and half a pound of bacon.” She tearfully eats the makeshift southern cuisine, even though “it doesn’t taste like anything I really wanted to have.” But she keeps trying, squirreling away bags of frozen collards when she finds them at the grocery store, and begging the butcher for neck bones: “Having those wrapped packages in the freezer reassures me almost as much as money in the bank. If I wake up with bad dreams, there will at least be something I want to eat.”12

But recreating home cooking with subpar northern ingredients did not diminish the bad dreams that haunted her nights, and Allison kept running. By the end of the decade, she had moved even further away from the South, to Northern California, “literally,” she confessed to a southern feminist expat friend, “to save my life.” Like Walker a few years earlier, this “geographic solution” enabled Allison to truly delve into the novel she wanted to write about the South. Out West, she wrote a friend, “I am holding my inner doors open, trying to heal myself and to write out my rage and sense of injustice, and that means I have been carefully reaching out to all I ran away from in the past.” While leaving enabled Walker to reassess, reclaim, and rewrite the subjugated lives of her foremothers, Allison’s departure from and infrequent returns to the South allowed her to look safely inward at the traumas wrought by classism, homophobia, and misogyny that characterized her experiences there.13

For Allison, as for Walker, writing was a therapeutic measure, a safe outlet. “Write I did, night and day, something, and it was not even a choice,” Walker explained. “When I didn’t write I thought of making bombs and throwing them. . . . Writing saved me from the sin and inconvenience of violence.” When she wasn’t writing, Walker fantasized about “shooting racists” and of “doing away” with herself—of attacking both the dehumanizing system and its target. The acts of leaving and writing protected her, as the story/essay title “Saving the Life That Is Your Own” denotes. The title is a take on O’Connor’s famed short story “The Life You Save May Be Your Own,” which is about transience and the search for meaning. But Walker was not simply on an individual rescue mission. Her work has also had the effect of exposing the lies of white supremacist patriarchy, particularly through her resilient, resourceful, and resistant Black female characters, some of whom were based on Walker’s own ancestors. Like Walker, writing from outside of the South, Allison also struggled with representations of her past and her region, finding few models for white, working-class women writers. In Trash (1988), naming her painful childhood and peopling it with characters who were composites of her “trashy” relatives was for Allison a powerful act of southern working-class reparation: “[T]o say that there is something good and valuable in that heritage is an act of rebellion, and almost revolutionary.” She “wrote out the rage,” and began to process the intimate, gendered violence of southern poverty that would characterize her first novel four years later.14

It took Allison a decade and dozens of revisions to fictionalize her southern memories until they became the National Book Award–nominated bestseller Bastard Out of Carolina (1992). In Bastard, Allison shed the shackles of autobiography and focused on emotional rather than historical truth; it was a way of confronting her past without actually returning to the southern scene of the crimes. This truth-telling through fiction both made Allison famous and reinvigorated her relationships to and within the region. Eventually, Bastard “provoked necessary conversations that people had been avoiding for decades,” and it gave Allison and her sisters a “language to talk about things that we had avoided talking about,” a way of examining their past and “put[ting] in place some protection.” The result, then, was both the redemption of working-class southern white women in her fiction and the renewal of regional relationships damaged by socially enforced silences.15

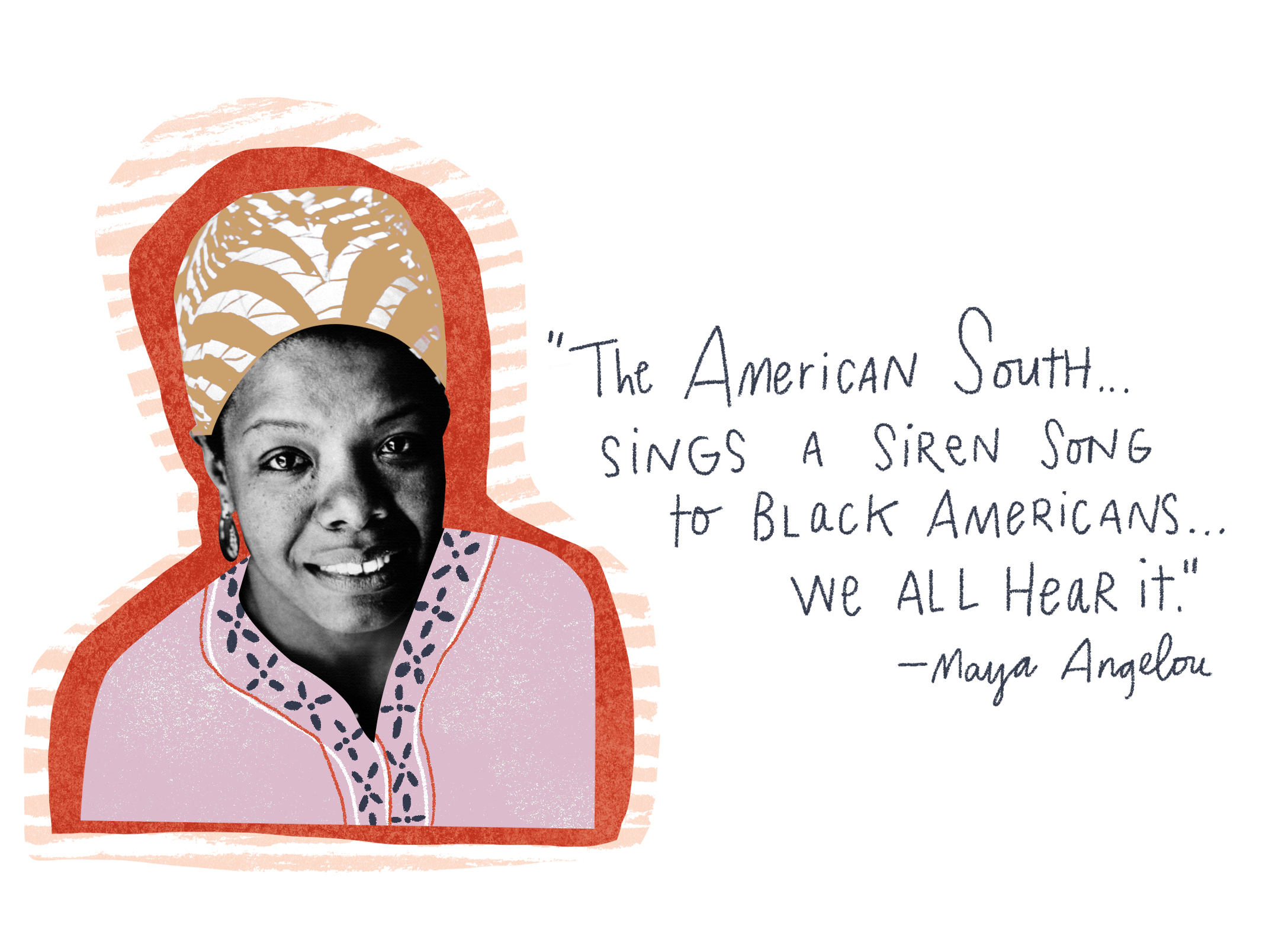

Walker and Allison are part of a larger feminist migration of women writers who left the South during and after the Women’s Liberation Movement. Like the Great Migration, which reversed, with about half a million African Americans moving back into the South after 1970, something similar has happened with this smaller exodus of southern women writers that fled the various and compounding oppressions of the region. Rita Mae Brown, a feminist activist and writer who grew up in Florida, abandoned Los Angeles for a Charlottesville, Virginia horse farm in the late 1970s. Maya Angelou returned not to Stamps, Arkansas, the hamlet she “left forever” four decades before, but to Winston-Salem, North Carolina. “The American South,” she explained in Ebony magazine, “sings a siren song to Black Americans.” While some choose not to follow its dictates, she wrote, “we all hear it.”16

The old ambivalence is still there, but the in-migrants return to ever-changing southern communities. Tayari Jones, fresh off of her much-celebrated fourth novel, An American Marriage (2018), recently returned to her hometown of Atlanta to teach at Emory University. Like many writers, Jones moved to New York to be closer to the publishing industry, but after years of New Yorkers treating her like she “came to Brooklyn on the Underground Railroad,” she headed back to Georgia to put her “roots in the ground.” Jones has returned to a vastly changed Atlanta, where old neighborhoods are unrecognizably gentrified, yet she still runs into people like her kindergarten teacher at the grocery store. “There’s more to coming home than you might think,” she explains, and her next project will grapple with this “unique experience” of “having gone north and then coming back south.” For some southern women writers, then, moving back home brings up complex emotions. The ambivalence does not disappear when they traverse the Magnolia Curtain with their U-Hauls. Returning as a feminist writer to a region that is still known as a bastion of white supremacist patriarchy is not simply a personal move; for those who do so in the early twenty-first century, it can also be a political reckoning.17

The ambivalence does not disappear when they traverse the Magnolia Curtain with their U-Hauls.

For Jesmyn Ward, perhaps the foremost southern writer of this century, home is the Mississippi Gulf Coast. In Ward’s memoir, Men We Reaped (2013), the theme of leaving, of both escaping and forced removal, is palpable: survivors relocating after Hurricanes Camille and Katrina, Ward’s family moving around the Gulf Coast in search of affordable housing and better jobs, Ward herself fleeing the South to get an education. Her family lived in California when she was very young, but “for all of us,” Ward writes, “the pull home is an inexorable thing.” Her mother Norine, however, did not miss the Deep South from out West; being away was a form of liberation for her. Unlike the oppressive landscape of Mississippi, with its “dense thickets of trees all around” and heavy rain clouds creating a low ceiling that blocked the stars, Norine “liked the freedom of [California], the vista of the cities rolling themselves out over the hills.” But they returned at her husband’s insistence, and Ward writes that her mother “buried her dreams on that long ride from California to Mississippi.” Returning home, coming back to the South, was both a physical and a historical journey, something like going back in time to a previous generation, as Norine realized that “her mother’s story would be hers.” Ward’s grandmother raised seven children on her own after her husband left, and Norine “felt smothered” having to relive this history.18

For Ward, like Walker and Allison before her, the escape hatch from this gendered cycle was education. As a teenager, she contemplated applying to boarding schools to get out of Mississippi as soon as she could, but her mother flatly refused, saying she needed help raising Ward’s siblings. Ward felt this acutely as a historical burden: “When she said that, I felt all the weight of the South pressing down on me, and it was then that I resolved to leave the region for college.” She left in 1995 to attend school at Stanford, but she was plagued by that southern “siren song.” Debilitated by a “crippling case of homesickness,” she always went back to Mississippi during breaks. She had nightmares about devastation at home, dreaming of fires in the “woods surrounding my mother’s house, that they were being razed and burned,” and she cried often, wondering, “How do I get back? ”19

“How could I know then that this would be my life: yearning to leave the South and doing so again and again, but perpetually called back to home by a love so thick it choked me?”

And so she returned. After earning her BA and MA at Stanford, Ward drove back to Mississippi, simply “tired of being away.” But her journeys did not end there. There were no jobs for Ward on the Gulf Coast, and she had to expand her search wider and wider until she found herself interviewing in New York. Tragedy abounded—five sudden deaths in four years—and after the death of her brother at the hands of a drunk driver, Ward went to the University of Michigan to work on her MFA, where the old ambivalence returned with physical manifestations, and she had difficulty breathing due to a combination of homesickness and grief. As she and her cousin drove south one summer, her congestion dissipated and then disappeared completely as they edged into the region: “By the time we crossed the Ohio River over to Kentucky’s rolling green hills, I could inhale and exhale through my nose.” Although home for Ward was “more populated by ghosts than by the living,” so, too, was her life away from the South haunted. “How could I know then,” she asked, “that this would be my life: yearning to leave the South and doing so again and again, but perpetually called back to home by a love so thick it choked me?”20

Finally, in 2010, Ward succumbed to this smothering love, embraced her ambivalence, and returned home to coastal Mississippi. In 2018, she wrote that she understands the confusion about why she would choose Mississippi, of all places, with its history of slavery, lynching, Jim Crow, fire hoses, and guns, and its present-day racism and systemic inequality. But Mississippi for Ward is also seafood boils on the Fourth of July, and her sister swaying to Al Green on a hot summer night, and her grandmother on a porch swing, telling stories to the children. It’s also the place where Ward wrote her most recent novel, Sing, Unburied, Sing (2017), in which, as National Book Award judges explain, “the living and the dead confront racism, hope, and the everlasting handprint of history.” That reckoning is not limited to the pages of her fiction. In Ward’s small town of Pass Christian, the local library has chosen The Fire This Time (2016), a book Ward edited about what it’s like to be Black in twenty-first-century America, for its reading program. She now envisions community dialogues on race, days filled with family, a hurricane-proof home “in a clearing of piney Southern wood,” a small garden, and neighbors who look after each other. And she hopes that, after her death, her children will see it as their “refuge,” as well. “I hope,” she wrote in Time recently, “that at least one of them will want to remain here in this place that I love more than I loathe, and I hope the work that I have done to make Mississippi a place worth living is enough.”21

When women writers flee the South, they often dedicate their life’s work to coming to terms with the simultaneously systemic and intensely personal traumas of being raised there. Writing from far away, they might offer the South the solution of woman-centered, self-sufficient Black communities, like Walker in The Color Purple. They might use the brutally honest retellings of trauma as therapy for the queer white working class, as Allison does in both her fiction and nonfiction. In their writing, they face down the wrongs wrought by the compounding, oppressive forces of white supremacy, socioeconomic discrimination, poverty, heteronormativity, and, as a common denominator of these varied experiences, the intergenerational demands that white southern patriarchy placed on these authors and their mothers and grandmothers. Ward’s recent relocation is a kind of “circulation,” a return to the South with the hopes of making good on the political promise of Walker’s itinerant process of reclamation begun in the early 1970s. While authors of previous generations had to leave to write about the South, Ward and others, decades later and with the migratory experiences of the previous generation as their guides, are returning to reckon with, redefine, and write from within the region in an attempt to make it a place of liberation rather than confinement. At the end of her memoir, Ward envisions a place after death that looks like her “true South”: a hot, sunny road lined with pine trees, along which her brother drives to pick her up, entreating her to “come take a ride” with him the way they used to cruise the coastal backroads. Ward writes of her profound grief, and of her mother’s hard lessons. Her narrative, her mother’s narrative, is both personal and historical; their individual stories reflect the broader intersectional contexts of women’s experiences in the region. They are the stories of women’s moves to and from the South, riven with hopes and tensions and loves and traumas. Women writers have long fled the various oppressions of the South, but many were called back, determined, as Tayari Jones put it, to “write about home from home.” “Hello,” Ward pleads plainly at the end of her memoir. “We are here. Listen.”22

This essay first appeared in the Women’s Issue (vol. 26, no. 3: Fall 2020).

Keira V. Williams is an expat southerner and a senior lecturer of history at Queen’s University Belfast. She is the author of Gendered Politics in the Modern South (Louisiana State University Press, 2012) and Amazons in America (Louisiana State University Press, 2019).NOTES

- Paula J. Giddings, When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America (New York: Bantam, 1985), 296; James N. Gregory, The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 11; Mary Weaks-Baxter, Leaving the South: Border Crossing Narratives and the Remaking of Southern Identity (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2018), 104, 58; Alice Walker, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Prose (Open Road Integrated Media, 2011), Kindle.

- “‘The Radical South,’ Presented by Dr. Mab Segrest,” English Department at Ole Miss, April 12, 2017, https://olemissenglish.com/2017/04/12/the-radical-south-presented-by-dr-mab-segrest/; Cris South, Feminary 12 (Spring 1982): n.p.; Anonymous, Feminary 12 (Spring 1982): n.p.; Anita Cornwall, “Backward Journey,” Feminary 12 (Spring 1982): n.p.; Jennifer L. Gilbert, “Feminary of Durham-Chapel Hill: Building Community through a Feminist Press” (master’s thesis, Duke University, 1993), 74–75.

- Walker, Gardens, 161, 253, 143, 164, 21.

- Walker, Gardens, 11, 160, 269, 37, 231, 35; Deborah G. Plant, Alice Walker: A Woman for Our Times, Women Writers of Color (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2017), 50, 51.

- Walker, Gardens, 248, 254, 317, 167, 166, 170; Plant, Woman for Our Times, 50.

- Walker, Gardens, 44, 45, 57

- Walker, Gardens, 57, 58.

- Walker, Gardens, 59, 93–115.

- Walker, Gardens, 49, 356, 143; Alex Clark, “Alice Walker: ‘I Feel Dedicated to the Whole of Humanity,’” Guardian, March 9, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/mar/09/alice-walker-beauty-in-truth-interview.

- Shirley Abbott, Womenfolks: Growing Up Down South (Ticknor and Fields, 1983), 189, 190.

- Shirley Abbott, “Travelin’ Women with a Travelin’ Mind: Why Southern Women Leave Home,” Boston Review, February 1983, 7–12, Shirley Abbott folder, Dorothy Allison Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University; Dorothy Allison, Skin: Talking About Sex, Class, and Literature (Ann Arbor: Firebrand Books, 1994), 19.

- Carolyn E. Megan, “Moving Toward Truth: An Interview with Dorothy Allison,” Kenyon Review 16, no. 4 (Autumn 1994): 73; Cris South to Dorothy Allison, October 1, 1988, “Correspondence, Mar. 88–Jan. 89” folder, box 38, Allison Papers.

- Allison to Nancy Bereano, July 13, 1990, “Correspondence, Mar. 90-1/9” folder, box 38, Allison Papers; Megan, “Moving Toward Truth,” 77; Joan Nestle to Dorothy Allison, January 13, 1989, “Correspondence, Mar. 88–Jan. 89” folder, Allison Papers.

- Walker, Gardens, 378–379, 3; Flannery O’Connor, “The Life You Save May Be Your Own,” in A Good Man Is Hard to Find and Other Stories (New York: Harcourt, 1955), 51–66; Mary Helen Washington, “An Essay on Alice Walker,” in Alice Walker: Critical Perspectives Past and Present, ed. Henry Louis Gates Jr. and K. A. Appiah (New York: Amistad, 1993), 39; Allison to Minnie Bruce Pratt, May 3, 1989, “Correspondence, Jan. 88–Jan. 89” folder, box 38, Allison Papers.

- Kate Brandt, Happy Endings: Lesbian Writers Talk about Their Lives and Work (Tallahassee, FL: Naiad Press, 1993), 11; Dorothy Allison, Trash (Ann Arbor: Firebrand Books, 1988), 15.

- Dana Hull, “Dorothy Allison, Rebel Belle,” Washington Post, November 24, 1995.

- Weaks-Baxter, Leaving the South, 175, 131; Carol B. Stack, Call to Home: African Americans Reclaim the Rural South (London: Little, Brown, 1996), 6–7; Martha Chew, “Rita Mae Brown: Feminist Theorist and Southern Novelist,” in Women Writers of the Contemporary South, ed. Peggy Whitman Prenshaw (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1984), 200; Melanie Kembrey, “Barbara Kingsolver: Her Life Is Quiet, Her Fiction Is Loud,” Sydney Morning Herald, February 12, 2018; Maya Angelou, “Why Blacks Are Returning to Their Southern Roots,” Ebony, April 1990, 44, 46; Walker, Gardens, 52; Caroline Cox, “Author Tayari Jones on Moving Home to Atlanta and Getting a Phone Call from Oprah,” Atlanta Magazine, October 10, 2018; Ryan Pait, “Tayari Jones Updates Us on Her Year of Oprah,” Houstonian Magazine, April 19, 2019. Credit for the phrase “Magnolia Curtain” goes to my mother, Joyce Williams, a lifelong teacher of southern literature, who passed away a few years ago but would have had a lot to say about this article.

- Jesmyn Ward, Men We Reaped: A Memoir (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), 9, 16, 49, 17, 47, 70, 146, 60, 83, 131, 129.

- Ward, Men We Reaped, 195, 213, 21, 22, 214.

- Ward, Men We Reaped, 213, 6, 21, 23, 67, 195.

- Jesmyn Ward, “My True South: Why I Decided to Return Home, Time, July 26, 2018; “Sing, Unburied, Sing: Winner, National Book Awards 2017 for Fiction,” National Book Foundation, accessed March 3, 2019, https://www.nationalbook.org/books/sing-unburied-sing/.

- Ward, “My True South”; Cox, “Author Tayari Jones on Moving Home”; Ward, Men We Reaped, 252.