It may seem impossible, given climate change and ISIS, mass shootings and growing inequality and disregard for Black life, sexual assault and Russian hacking and the opioid epidemic, to worry about any other single thing, but history too is in trouble. I do not mean history as content. Beloved television shows and films take place in the past. Books about the founding fathers and the Civil War sell. Football coaches teach history to bored high school students. And some people actually get tickets to Hamilton. No, the problem is not content. The problem is form. Grand linear stories—those no longer tenable narratives of progress and decline—play now as fantasy fiction: Star Wars films, Game of Thrones episodes, and the stories alt-right guys tell to justify their anger. There are simply too many strands, too many pasts, and too many peoples and places to understand history as moving in unison. Alternately, the flatness of our always present digital backlist of sounds, images, stories, and styles pulled from multiple places and eras makes it hard to experience history as the feeling of being alive within the stream of time. History—the change we are living through and making—is working against history as historians understand the term, the meaning that emerges from context, contingency, and causation. Or, to put this another way, our content is erasing our form. Marveling at alternate worlds, we forget that history can be a mode of analysis, a tool for revealing complex webs of cause and effect.

And this is why we need art more than ever now, because artists make us think deeply about form. Qualities like light and color, mass and volume, composition and line, shape our perception of how the parts relate to the whole. They influence our understanding of content. And they invite thinking about the relationship of representation and reality.

We understand the South as a major site of U.S. history, a landscape littered with evidence of the past, from plantation slavery and the Civil War to the Civil Rights Movement. What fewer people know is that the region is also an essential location in the history of photography. For photographers making work in the world rather than the studio, the South has been a rich place to make images. At odds with the grand story of America as expanding freedoms, the region has been understood as both the national reservoir of cultural authenticity and the national cesspool of white supremacy. The contradictions give artists a lot to look at. An admittedly partial list of photographers who have done important work in and about the U.S. South might start with Doris Ulmann and Walker Evans, Marion Post Wolcott and Arthur Rothstein, Clarence John Laughlin and Ralph Meatyard, Eudora Welty and Gordon Parks, Emmet Gowin and William Christenberry, William Eggleston and Dawoud Bey, Sally Mann and Carrie Mae Weems, Deborah Luster and Susan Lipper.

In much of this work, artists render the forms of history visible by returning to photograph the same place, people, or subjects at different times. They restage old images or revisit places photographed by others. They employ old photographic processes, formats, and materials. And they consciously go back to former histories, to older Souths and to the relationships people have constructed with these pasts. In their work, return as a practice, a process, a subject, and an aesthetic structures time and, in this way, marks and makes history. How we understand and give form and meaning to change over time becomes as much the subject of this work as what exists on the other side of the lens.

Artists render the forms of history visible by returning to photograph the same place, people, or subjects at different times. They restage old images or revisit places photographed by others. They employ old photographic processes, formats, and materials.

Photography, of course, always shows us history as content: every image is in some sense a representation of a moment in the past. But photography can also show us history as form—how the past gives rise to the present and sets up the possibility of the future. Alone, a single photograph cannot tell us much about this kind of history. A photograph needs context. That context can be indexicality—the relationship of the photograph to the world; or that context can be visual culture—the photograph’s relation to other images, including other photographs. Context enables comparison. “History” is one of the meanings that can be produced by the gap between a photograph and its subject or a photograph and another image.

Yet even a single photograph can help us practice a conceptual skill essential in learning to think historically. To understand the relationship between past and present, we have to imagine both sameness and difference simultaneously, how people in a different place and time are both like and unlike us. As with history, photography as a medium asks us to think with rather than through a contradictory sameness and difference. The photograph has a documentary function in registering a material world outside the camera. And yet, the photograph is also always a representation—it is not a piece of the world, like a fossil, but a reference of reflected light. History is one of the meanings that can be produced at this juncture of difference and sameness.

Part I: A Circular Opening

Return means coming back to a place that grounds you. It means rooting yourself in a geography and a community. It means to say or put or send or feel or give back your attention or your presence or your affection or your verdict. It means to yield or to make. In his attention to the cycles of life, to the circle as a form, and to his favorite subject, his wife Edith, the Virginia photographer Emmet Gowin has made return a central theme of his art.

I’ve been to Emmet and Edith Gowin’s place about half a dozen times now, the road-end cluster of white wooden houses in Danville, Virginia, my own version of return. After an almost twenty-year career deconstructing romanticisms in the name of history—perhaps the single most important thread through all of my intellectual work—I come back like the moths drawn to the light behind the bedsheet, the insects that Emmet Gowin catches and pins in his current body of work. When I visit, the Gowins are always there, and some shifting configuration of Edith’s family stops by, the sisters Mae and Helen and Ruth and their husbands and children and grandchildren. The web of the Danville family is complicated, rich, and deep. Almost half a century after Emmet began making serious photographs of his wife Edith’s family, this tangle of people and houses remains the place where Emmet makes his art, even when he is photographing other subjects, the place that inspires him. Together, he and Edith and their family and this place have returned a body of photographs that have something to tell us about not just the history of photography but about how photography can help us think about history.1

The Gowins’ hometown of Danville is a small southern city known more for its factories and its history of civil rights violence than its art. While Emmet’s father was a Methodist minister, Edith’s mother went to work at the Dan River Mills after Edith’s father died. Many of her relatives worked at the mill too or at related businesses. In 1960, as the southern student sit-in movement spread across the South, protests in Danville came to a head over segregation at the Memorial Library, a public facility that doubled as a site of Confederate remembrance. Three years later, mass demonstrations emerged again, this time over African Americans’ lack of representation in municipal government and unequal access to city services. Police officers and deputized garbage collectors armed with fire hoses and clubs attacked a prayer vigil, injuring almost fifty participants. Home from Richmond, where he was studying design and photography at the Richmond Professional Institute, Emmet took his camera into the streets. A young white man who knew the town well could slip through the crowds of demonstrators and law enforcement officials. Naïve and ambitious, he packaged up his prints and his negatives and sent them off to Life magazine. He never got a reply. Instead, Gowin made his career with a different set of pictures, a series of intimate images of the white working-class family life at the center of his own emotional and domestic life.2

Gowin calls the image Nancy, Danville, Virginia (1965) his first real photograph. He was three weeks into grad school in photography at the Rhode Island School of Design when he received military induction papers and had to return to Danville to talk to his draft board. While he was home, his four-year-old niece Nancy “assigned him” to take a photograph of her lying on the ground with her seven favorite dolls. Thinking about Vietnam and not even sure his borrowed film holders were loaded, he made this image.3

In it, the sun is low in the fall sky. Nancy lies on a tarp of dark plastic whose folds reflect the light, her dolls, naked and in various states of dress, tumbled about her, their legs and sometimes bellies exposed, their moveable eyes closed, their painted eyes staring up or, in one case, at the camera. The long, black shadows of the tripod and Gowin’s legs cut diagonally upward from Nancy’s cowboy boots across the lower frame. The ground is a tracery of sticks and vines. Nancy’s eyes, like many of the dolls, are closed against the sun, and she covers her brow, one eye, and part of her cheek with her hand. Her uplifted elbows pull up her dress.

Nancy, Danville, Virginia offers an alternative reality to Vietnam: another kind of flesh on the ground, bodies touching the black plastic of bags, limbs tumbled about, eyes closed or staring, clothes askew. At Gowin’s meeting with his draft board afterward, officials suggested he ask for conscientious objector status. He succeeded.

Two years later, Gowin made the photograph Edith, Danville, Virginia (1967) at Edith’s grandmother’s house where he, Edith, and their baby son Elijah were spending Christmas with family. Hoping to capture something about what his domestic life was like then, Gowin returned to his favorite subject. In a story the artist has often told, a student at Princeton, where he later taught, asked him how many photographs of Edith he had made. He answered, “Not enough.”4

In this 1967 Edith portrait, return is subtly visible everywhere—in the ritual of visiting family, holiday cards received each year and taped to the doorframe, the baby bottle on the mantle that suggests the presence of the couple’s child and the cycle of life, even the cases of returnable Coke bottles stacked on the kitchen floor. Yet, like the picture of Nancy and her dolls, this image of intimacy and domesticity, too, in Gowin’s words, “lived with Vietnam.” In the Danville family images, Gowin created an intimate alternative to an American history of escalating global war.5

Around this time, Gowin began using a lens too small for his 8 × 10 view camera. In order to create standard-shaped images, he cut the rectangle out of the circle. By 1970, he began thinking about the dark edges outside the circle as interesting, as a space of transition. The circle transformed these edges into a concave, curved space that pulled the viewer into intimate, interior scenes or, alternately, pushed exterior scenes like landscapes out into the world. The circle echoed the eye and provided a portal, a window into the matriarchal family circle and the grouping of Danville houses. And the vignette effect made the photographs look instantly old, pushing against any easy comparison of them with family snapshots.

In Gowin’s photograph Edith, Christmas Morning, Danville, Virginia (1971), it’s Edith again, Christmas again, and Danville again—the rituals of going “home” for the holidays and putting up the tree and the decorations and selecting and wrapping and unwrapping the gifts. The circle suggests a peep hole, a view inside a sheltered and yet also subtly erotic space. The outline of Edith’s body is visible through the white nightgown as she stands in front of the window, her hair overexposed, her body on the right melting into light. On the floor, among the ripped paper, little Elijah makes the cars on his new race track go around and around.6

Two years later, Gowin hauled his camera into the kids’ treehouse and shot the photograph View of Rennie Booher’s House, Danville, Virginia (1973) from afar. In the South, where snow is rare, taking these kinds of photographs is a ritual. This practice makes these kinds of landscapes paradoxically common. In this image, Gowin’s circle becomes a telescope we use to peer through the tree limbs and across the field returning to scrub and the little house and outbuildings in the distance. From the treehouse, Gowin remembers feeling “how beautiful the place was. The family’s lives had been poured into that piece of land, and the land was what was left” as the older generation died. Taking this photograph changed his idea of what an intimate picture could be and formed “a natural end” of the Danville project.7 As a form, the circle pulled him outward in widening rings away from close-up shots of people into the yard and woods, up into the trees, and, in later bodies of work, into the sky, where he shot the round, curved forms of pivot irrigation systems, water treatment plants, and the craters left by bomb tests.8

The circle of Gowin’s Danville family images creates a different kind of public history. Coming back, revisiting, reimagining, and repeating become ways to register the history of this family and its relation to the larger history of the United States in the late 1960s and 1970s and to the history of art. Gowin’s images coexist with widely circulated documentary photographs of the civil rights movement that often present white working-class southerners as the enemy, the people publicly fighting to keep segregation. Many of them did. Activists and journalists were certainly not wrong to use photographs to condemn white supremacy and violent attacks on protestors. But not all working-class white people in the South shared these segregationist politics.9

Gowin’s family pictures show us something else, something rarely seen in art in the late sixties and seventies—an intimate, inside view of white working-class southerners, not as grotesque or romanticized others or as political enemies but as members of a close, extended family. He gives us children and older folks, people with time to pose for his slow camera. He reveals the loving relationships that will be severed when young men without his middle-class options go off and die in Vietnam. And he asks us to think about the photographs he cannot take, parallel images of Vietnamese families enjoying holidays and picnics, Vietnamese children with their games and toys.

Gowin’s care—both his emotional connection and his craft—elevates what critics at first panned as a “snapshot aesthetic” into a vision of what remains of beauty and goodness in a world at war, of the transcendence on offer through everyday human intimacy. His practice of making art with his extended family, in turn, transforms their private world into something monumental, something to value, something, in his words, on par with the biblical and mythic subjects of Renaissance art. From this perspective, Edith alternately looks like a Madonna, her skin radiant with light, or a Venus, holding the fertility of the world in her curves. Her older female relatives who run this world project the craggy dignity of burghers’ wives. The split watermelon and turkeys appear transported from Dutch still life paintings. Gowin’s photographs make this working-class southern family into the subject both of art and of history.10

Part II: The Place That Grounds You

In powerful ways, most photographs of southern people and places exist in a more or less explicit conversation with the images shot by photographers working for the federal government during the 1930s and 1940s. New Deal officials understood the region as a problem during the Depression, a “poor” and “backward” place in need of federal intervention. The Farm Security Administration’s Roy Stryker sent photographers out to gather the evidence. Marion Post Wolcott, Dorothea Lange, Ben Shahn, Arthur Rothstein, Jack Delano, Walker Evans, and others made work there that taught viewers to see the South as at least partially outside of contemporary time, a place where the past coexisted with the present. In a 1936 Evans photograph of a country store near Selma, Alabama, contemporary advertisements for Coke and other products jostle for space on the worn façade of an already old-fashioned wooden building with a false front. In another 1936 Evans photograph of a street in Vicksburg, Mississippi, electricity meters and signs pushing Coke, Camel cigarettes, and 666 cold preparation adorn the unpainted wood siding of an old warehouse or shed converted into a Black barbershop.11

Working in the South and elsewhere, FSA photographers shaped a documentary practice that dominated American photography for decades. Sharp black and white photographs of poor people, rural places, and vernacular architecture produced a set of codes about what counted as real that retained its power through the second half of the twentieth century. The contradictions—the coexistence of old and new buildings and technologies, rich and poor people, the products of industrial mass production and traditional craftsmanship—created visual interest. The tonal range worked as a metaphor for race. And the crisp focus embodied the presence of the photographer with her deep and discerning vision. Unintentionally, fsa photographers made parts of the rural South, like the Appalachian counties of Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia; the Mississippi Delta; and Hale County, Alabama, into sites that photographers would return to for decades. Over time, these places became de facto open-air museums where poverty, vernacular culture, and a material sense of the past in the present seemed to be permanently on display, even if as time went on you had to crop the Dollar General out of the frame.

My own experience of return began in a place far from this kind of famous: Jefferson Davis County, Mississippi. There, my Mississippi grandfather’s stories about the past transformed the buggy cow pastures and swampy woods of Jefferson Davis County into a dense and magical landscape layered with traces of the people, buildings, and relationships that had come before. Driving the backroads, he would point out the open window of his GMC truck to a spot where the jonquils bloomed in a line in an empty field and conjure the now vanished farm with his words. Or he would stop suddenly and pull onto the sandy shoulder of a dirt road and say, “I think this is it.” Bushwhacking through tangles of blackberry bushes and scrub, he would uncover a choked spring he remembered from his youth. Miraculously—to this city girl at least—we would kneel and drink the clear and cool and delicious water straight from that muddy ground.

The next summer, when I left my parents’ house in suburban Atlanta and visited again, we would drive the same circuit. We would return. By holding place still—revisiting a spot in the present and telling me stories about its multiple pasts—my grandfather opened up the layers of history like an archeologist at a dig. He taught me to see passing time.

I first understood that the artist William Christenberry, too, had these grandparent summers when I took my twin daughters, then about seven, to see the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s show of the artist’s photographs, paintings, and constructions, aptly titled Passing Time. A single parent, I had a brilliant strategy for viewing art: the free Smithsonian, plus bribery. The girls would consent to look at those “boring” pictures on the walls for exactly twenty-eight minutes if rewarded with trips to see the dinosaurs, gems, and airplanes and rides on the carousel. But when we entered the Christenberry exhibit, they literally waved their hands in glee. In their own young way, they seemed to sense that the sculptures, photographs, paintings, and drawings of the same buildings presented both sameness and difference. The way they talked about what made this art magical reminded me of summer drives with my Mississippi grandfather. This art helped them see history, too.

Much of Christenberry’s art is about Hale County, Alabama, a place he fell in love with as a child spending summers on his grandparents’ farms. From 1968, when he took a job teaching at the Corcoran College of Art and Design in Washington, D.C., until his health began to decline in the early 2000s (he died in 2016), he made regular trips back to Alabama. There, he photographed vernacular structures he loved. Back in D.C., he printed his images and produced sculptures and paintings of these buildings as well. Though he worked in multiple mediums, returning to this area was his photographic practice, the only place he made serious pictures.12

Hale County, of course, was already famous in photography circles for the work Walker Evans made there in his collaboration with the writer James Agee, later published in the book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. In 1935, Evans shot a general store at a crossroads town in Sprott, Alabama, in Perry County, next door to Hale. In 1936, he took a photograph of a nearby church. In Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Agee described the moment the two artists first saw St. James Missionary Baptist: “It was a good enough church from the moment the curve opened and we saw it that I slowed a little and we kept our eyes on it. But as we came even with it the light so held that it shocked us with its goodness straight through the body, so that at the same instant we said Jesus.” About a quarter of a century later, Christenberry met Walker Evans, and the older photographer became the younger man’s mentor and friend.13

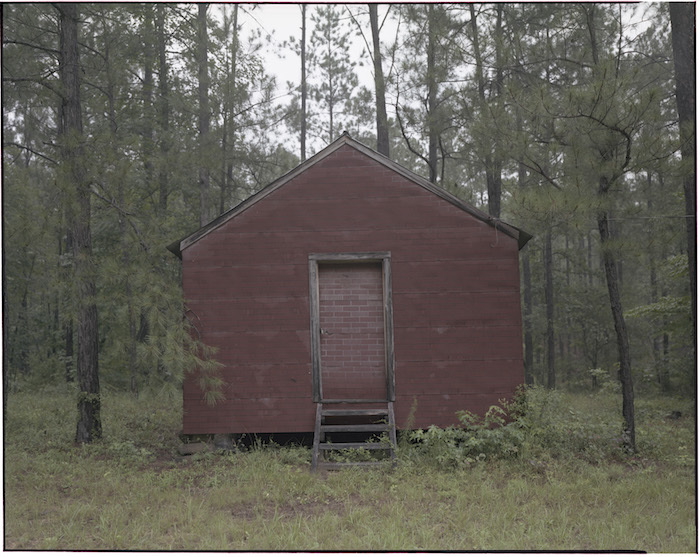

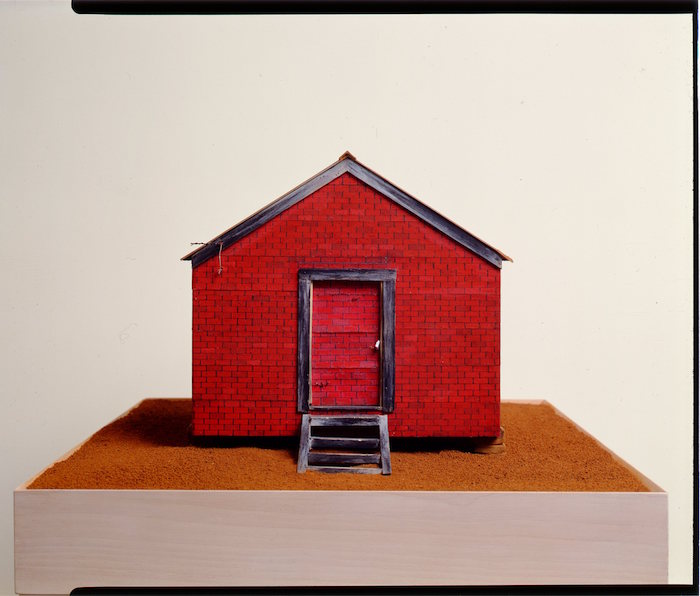

Around 1974, Christenberry discovered a building standing alone in the woods of the Talladega National Forest in Hale County. Christenberry loved the way someone had put artificial brick siding on the door of the house as well as the walls. He used his Brownie camera to make a photograph he dropped off at a drug store for development. Almost a decade later, he made another photograph, Red Building in Forest, Hale County, Alabama, 1983. In 1984 and 1985, he used his photographs and his memory to construct a sculpture of the building. In 2000, he made a painting of the structure. He made these bodies of work about other buildings, too, including Green Warehouse, Newbern, Alabama (1973–2004).14

Christenberry even returned to places Evans photographed. That Sprott church, in particular, drew his attention. In an interview, he describes discovering the church while driving in his VW from D.C. to his parents’ house in Alabama with his wife and their baby. In a photograph he made in 1971, the dry air of winter produced a deep blue sky. In 1974 and 1975, he made a sculpture of the Sprott church, using his photographs and thumbnail sketches he drew of the back and sides. He also continued to return to make photographs, including an image shot in 1981. Christenberry described in an interview how he loved the way this building sat isolated and proud in the landscape and the rare symmetry of the two towers. Sprott church, he asserted, was simply “the most beautiful piece of vernacular church architecture” he had ever seen. By the time he took a 1990 photograph, the towers he loved so much were gone. He then made another sculpture, Sprott Church Memory, in 2005.15

In these and related bodies of work, Christenberry explores, in his words, the effects of “time, mankind, and the elements” on the vernacular structures he loves. Like the annual pictures of school kids, his photographs reveal his subjects aging. Paint fades, cracks, and peels or disappears entirely under a new coat. Rafters sag and roofs give way. Window glass cracks and falls out of frames. Siding rots. Trees and vines grow over structures or are beaten back. Walls fall in. Time passes. Christenberry comes back and documents what is there. “The place is so much a part of me. I can’t escape it and have no desire to escape it,” he tells an interviewer. His work, in his words, is “a love affair—a lifetime of involvement with a place. The place is my muse.”16

Over time, as the trips continued, the act of return became as much Christenberry’s subject as the structures themselves. Retracing his own paths in and around Hale County began to function as a ritual practice, a way to give his attachment to place a concrete form. The photographs in this sense function as evidence of this act of worship, of this pilgrimage.

For some viewers, Christenberry’s work suggests Mircea Eliade’s concept of “eternal return.” The repeated gestures of religious rituals dissolve everyday human or “profane” time and catapult participants instead into “mythical” or sacred time. From this perspective, Christenberry’s returns represent Hale County, Alabama, as a sacred space outside history.17

In important respects, all ambitious artists want their art to escape the time in which they work and live outside history. But to see Christenberry’s multiple series as exercises that pull Hale County out of the flow of time is to miss his careful attention to materiality and form. Christenberry tells us that things that exist in the world—even long romanticized vernacular artifacts of the rural South—do not stand still. But as they change, some formal traces remain; even a building in ruins suggests its former footprint and volume. His series of photographs makes visible the sameness and difference that is the very material of history. Circling back may seem like a contradiction but it is this return, in fact, that makes our awareness of the passage of time possible.

It is worth remembering that Christenberry, like Evans and Agee, was a white man enthralled by the Black church and other physical traces of Black vernacular culture. For white southerners, knowing about and appreciating the past could and often did coincide with a belief in white supremacy, even when we disqualify the fake history of the Lost Cause. The Mississippi grandfather that taught me to love history was also at times a Mississippi sheriff. Doing this job meant enforcing white power, often with a gun. At least once, he participated in the killing of an African American man that was at best a case of using excessive force and at worst a lynching.

But William Christenberry was not this kind of white southerner, and he did not love his particular southern place blindly. He faced his region’s violent white supremacy in another body of work he circled back to repeatedly in his career, his Klan Room Tableau. In this complex and changing installation, Christenberry explores the intersection between boys playing with war toys, fraternal organizations, a love of uniforms, and violent white male entitlement. The form and materiality of Christenberry’s work reproduces the Klan’s graphic brilliance, smirking silliness, and nauseating violence. As the alt-right engages in its own form of return, a fascist cosplay we only wish were past, Christenberry’s Klan Room looks horribly, brilliantly new again.18

Part III: Myth and Southern History

Southern artists have long used return as a concept and a practice and an aesthetic to wrestle with the issues of family and place, the region’s terrible beauty, and the burden of history. Like many people, I discovered Sally Mann’s work when she published Immediate Family in 1992. More than twenty years later, I made my own pilgrimage to the farm on the Maury River outside Lexington, the same property where Mann made this earlier work and where she lives today and has her studio. A 1993 photograph called Virginia, Untitled (Blue Hills) captures the beauty of this place with its velvet pastures rolling out to vistas filled with the stacked and pleated foothills and the small mountains of the Blue Ridge. The one-story house shaded by a circling veranda that Sally and Larry Mann built on a hill above the river could not be more different from Emmet and Edith Gowin’s white, wood-framed Danville house and still occupy the same state. But these are the places where these important artists are grounded. They are the places these artists return. And in that way they are also connected to Christenberry’s Hale County.19

Early in her career, Mann was deeply influenced by Emmet Gowin, and a journalist who visited Mann in Lexington around the time she published Immediate Family found one of the older Virginia photographer’s prints hanging in the house she lived in then, closer to town. Like Gowin’s Danville and Edith images, Mann’s photographs of her three children and other family members and friends combine the intimacy of family photos with the formal rigor of art. Occasionally, Mann seems to revisit Gowin like Christenberry revisits Evans. Her photograph of Virginia with grass clippings stuck all over her moist skin, Fallen Child, 1989, is not a literal return. In relation to Gowin’s Nancy and Dwayne, Danville, Virginia (1971), Mann’s subject is a different child, different grass, a different decade, and immediate rather than extended family. But this reworking of Gowin’s subject makes us look past the content of the image to its form, its existence as art. Like Gowin’s family pictures, Mann’s Immediate Family images are about the history of art as much as they are about family. She tackles mythmaking—a troubled tradition in southern history—on an intimate and personal scale, the world she as a mother and as an artist made with her children during summers by the river.20

As the artist confessed to a journalist in a 1992 interview, “I don’t remember the things that other people remember from their childhood … Sometimes I think the only memories I have are those that I’ve created around photographs of me as a child. Maybe I’m creating my own life.” As a mother, she makes this process more self-conscious and deliberate, collaborating with her children Emmett, Jessie, and Virginia in “spinning the story.” Using a shallow focus, sometimes placing a tube around the lens to produce a vignette effect, and directing her children’s gestures and expressions, Mann “fictionalizes” family photographs and distances her art from documentary’s more direct relationship with the world. In the most powerful of these images, like “The Ditch,” the mythical and the documentary coexist. We see the cycle of life and also her son Emmett and his friends playing at the river’s edge in the heat and sand of summer.21

In place of Gowin’s alternate history in relation to Vietnam, Mann gives us an alternate history of parents and children. All mothers, her work suggests, are artists of sorts, with access to a ferocious power to make the world of their children that we use sentimentalism to deny. Yet despite this power, mothers do not have complete control. Kids have their own bodies and minds. The world is out there. Injuries happen. Magic alternates with danger.

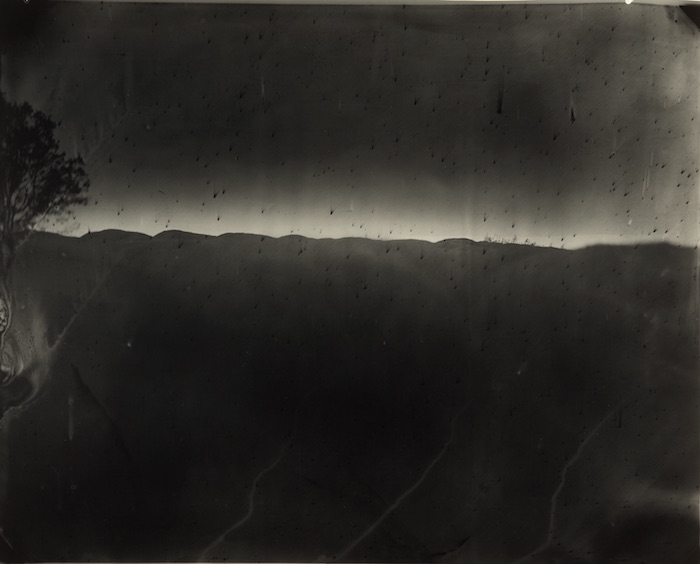

Like Gowin, Mann eventually backed away from her family scenes and out into the landscape that surrounded them, tackling more explicitly the politically and racially charged history of representations of her native region. Along with many other contemporary artists, she also began experimenting with what photographers call alternative processes—the use of old or non-commercial technologies, equipment, and papers and other materials. In bodies of work originally titled Deep South and Last Measure, Mann’s use of alternative processes make myth and history—not just what happened in the past but what is remembered as important and the effect of those memories on the present—as much the subject of her work as the people and places on the other side of her lens. When Mann turned in the mid-1990s to landscapes, she began to experiment with alternative film types and technologies. In the late nineties, she learned a nineteenth-century process, coating glass plates with sticky collodion to hold light-sensitive chemicals in order to produce negatives that must be exposed and developed in the ten or so minutes before the material dries. Photographers like Alexander Gardner and George Barnard used this same wet plate process to make their now famous images of Civil War battlefields. “Shooting with collodion,” Mann has said, enabled her to create photographs with “the appearance of having been torn from time itself.”22

While newer papers and the large size of the prints make clear Mann’s work is not historical reenactment, the photographs the artist makes from this process look instantly old. When she begins to invite the kind of flaws and accidents that nineteenth-century photographers considered failures, she adds yet another layer of history, a look that suggests her negatives too have been ravaged by the past. These effects replicate the way the passage of time increases the distance between all photographs and their subjects by erasing the indexical effect, the sense that a photograph presents a slice of the world. In these ways, Mann highlights the hand of the artist, the intermediate set of decisions and actions between the world and the camera. She expands the autonomy of her images as art. And she makes clear that this work is materially and formally about the history of photography as well as the history of the South.23

In her 2018 National Gallery exhibition, a section titled The Land collects images of Virginia farmland and other southern scenes originally part of the series Motherland and Deep South. Landscapes on which antebellum plantations have left their marks have been shot by Walker Evans, Eudora Welty, Clarence John Laughlin, Carrie Mae Weems, and others. Mann’s doubling—old subjects and old processes—works as a metaphor here for the history of history. Change over time is not just something that happens to people and societies and photographs but also to accounts of the past. Romanticism is not so much the effect and the affect here but the subject.

Deep South, Untitled (Valentine Windsor), a 1998 Mann photograph, revisits the ruin of a plantation house previously photographed by Clarence John Laughlin in 1941 and Eudora Welty in 1942. In Mann’s image, ghostly, heart-shaped leaves bleached out by the haunting heart-shaped light flutter between bare-brick columns. The ruined negative—the crack that runs through the right column, the emulsion that peels around the edges, and the drops and puddles made by wayward chemicals—echoes the broken houses and ruinous dreams of real-life versions of William Faulkner’s character Thomas Sutpen.24

In not titling these Deep South images, Mann refuses any documentary function. What she is after here is myth. Still, without specifics like the parenthetical (Emmett Till Riverbank) attached to another image called Deep South, Untitled, we would have no way to know that this overexposed (in terms of the film, the erosion, and the past) rut leading into a murky river is a site where some people believe the lynched boy’s body was found. And we have to know this detail as well as additional information provided by the catalog about Deep South, Untitled (Bridge on Tallahatchie), a related image of the rusty bridge where Till’s body was probably heaved into the river. Romanticism alone is too risky. Telling us what these sites are in the world makes visible African Americans killed to achieve southern whites’ dreams of mastery. In giving landscapes of Black loss an aesthetic treatment traditionally reserved for white nostalgia, Mann suggests a kind of artistic reparations. Yet most African American and many white viewers will not need to be reminded of white southern violence. Mann’s Till images seem to do the opposite of what she intends. Rather than “integrating” her Deep South history, they suggest instead a startling lack of attention to African American history and the central place within that past of struggles over the politics of representation.25

In a section of her National Gallery show called Last Measure, Mann turns to another important subject in both southern history and the history of photography, Civil War battlefields. In the early 2000s, Mann visited sites like Antietam and Cold Harbor, landscapes in which thousands of Americans lost their lives. Evoking the wartime images made by Gardner and others, she made a series of photographs that extend her experimentation with collodion almost into abstraction.

In these pictures, specks of dust and damage to the glass surface of her negatives create drips, puddles, and comets that evoke smoke, the heat and screams of battle, and flying bullets. Old equipment allows light flares and leaks. Often, the perspective seems almost ground-level, as if the earth itself is telling us what it felt like to be the site of so much horror and death. In Battlefields, Manassas (Veins), dark spots on a thin strip of glowing horizon suggest the rising spirits of the dead. Battlefields, Antietam (Last Light) beckons with painterly abstraction as drifts of ghostly smoke hint at a faint sky above a dark and marred earth, and bare branches like skeletal hands reach into the top of the frame to gesture at the place where they lost their flesh. There is beauty but not glory here, in Mann’s dark and elemental conjuring of scarred fields and groves and blood-soaked earth.26

Part IV: Sacred Circles

Small southern churches are everywhere in American photography—wooden churches with peeling or fresh white paint, country churches, churches squeezed between city buildings or taking over storefronts, churches for whites and churches for Blacks. Farm Security photographers shot them often, including Jack Delano, who photographed an example near Greensboro, Alabama, in 1941. Evans could not resist their vernacular architecture and made photographs of churches in multiple southern states.27

Eudora Welty photographed African American churches around the same time Walker Evans was working for the FSA. Somehow, she managed to get her camera inside a Black sanctuary and entice people to pose. She even got pictures of services in progress, including one called “Speaking in the Unknown Tongue.” All these years later, I still cannot fathom the contradictory combination of audacity and sympathy, given Welty’s whiteness, that the act of making these sensitive pictures must have required. Emmet Gowin, too, made photographs of Black churches in both the countryside and in Richmond between 1963 and 1965 for his undergraduate thesis at RPIRPI. Like Welty, Gowin shows us the buildings and the people. While other photographers like Evans, Christenberry, and more recently Mann have focused on the structures, Welty and Gowin present these churches not as aesthetic forms but as living spaces of Black life.28

What is it about white southern photographers and Black churches? What makes photographers return again and again to this subject? Churches were rare Black-controlled sites in the segregated South, and many churches founded then still survive, as buildings and as active congregations. Churches have been and remain the center of much rural southern life. For white photographers, they are visible and accessible sites of past and sometimes contemporary Black thriving.29

Churches themselves are places of return. Going to church produces its own set of routines, bathing and dressing up and traveling to the sanctuary. Services revolve around rituals and repetitions—an ordering of prayers and songs and Bible readings and sermons. Christian theology, too, takes shape around return: God returning to earth, Jesus arising from the dead, and believers returning to heaven. Churches are also the sites of dinners on the grounds, homecomings and reunions, weddings and funerals. All this ritual and repetition links a collective of people in the present to those in the past and projects the outline of their social, collective existence into the future. Churches are an essential place where people make and mark history.

In her most recent body of work on Black sanctuary—grids of photographs of African American churches and tintypes of swamps and riverbanks—Mann grapples with Black southern life, with what places and pasts look like from the other side of the color line. Like wet plate collodion, tintypes are a nineteenth-century photographic process revived by contemporary artists. In Mann’s tintypes, the reflective surfaces characteristic of the medium turn swamps and riverbanks where trees meet water into mirrored silhouettes whose multiplying images include saplings, vines, and the very faces of viewers. These watery places seem to float in that blurry space between myth and the world, as wall text reveals that she has made the images along the Blackwater and Nottoway Rivers, Nat Turner’s old territory, and in the Dismal Swamp, long a place of refuge for enslaved people hiding from their owners. What whites saw as wastelands of scrub and mud, Blacks saw as a haven. In the past, Black and white oppression and freedom stood as mirrored images—slavery and segregation meant that one side’s loss was the other side’s gain. This work pushes viewers to think about how much we still live with and in these historical forms. But like Mann’s representations of the Till lynching sites, these tintypes also raise questions about more recent history, about what it means in the twenty-first century for white artists to take on the project of representing Black sacred spaces.30

In making Black history visible on the landscape, Mann, like many white artists, leaves unexamined the Black presence in the history of art and, more specifically, the history of photography, topics of central importance to her own work. What would it look like to make this history visible? To make art that grappled with the history of Black image-making and Black artists’ historic engagement with the politics of representation?

The circle takes us back. “Time is mainly pictures,” the southern writer Reynolds Price has said. “After a while it is only pictures.” The linear narratives are dead. Return suggests another shape for historical narratives, another form. The circle enables us to go back and unravel the web of events to get to the decisive moment, a concept photography itself taught us to see.

The act of return is powerful. By going back and looking at something again, maybe we can see where it all went wrong. Maybe we can unwind it. Maybe we can pinpoint that one essential and probably photographed moment, return to it, and then move forward again in a different path. Maybe we can keep troubling the past until we figure out a new future. Alternately, by going back and looking at something again, maybe we can see where things went aesthetically right—the Gowin family, Christenberry’s building series, and Sally Mann’s spirits of the Civil War dead. In these bodies of work, the formal qualities of the art help us understand something we need to know about context, contingency, and causation. They help us see history.

This essay appears in the Backward/Forward Issue (vol. 25, no. 1: Spring 2019).

Grace Elizabeth Hale is Commonwealth Professor of American Studies and History at the University of Virginia and a 2018–2019 Carnegie Fellow. She is the author, most recently, of Cool Town: Music, Art, and the Promise of Alternative Culture in Athens, Georgia (University of North Carolina Press, forthcoming 2019). She has written for the New York Times, Washington Post, American Scholar, and Southern Cultures. She is currently working on “The Lyncher in the Family,” a book about her grandfather, a Mississippi sheriff, and white Americans’ inability to reckon with the history of white supremacy. Hale is codirector, with Lauren Tilton, of Participatory Media, a digital public humanities project on collaborative media-making in the 1960s and 1970s, and a collaborator in the University of Georgia’s Athens Music Project.NOTES

- Edith Gowin, remarks at the dedication ceremony for the inclusion of Emmet and Edith Gowin into the Danville Hall of Fame, Danville Museum, July 17, 2015: “This is where Emmet makes his photographs. This is home.” Newtown, Pennsylvania, where the Gowins live when not in Danville, is, in her telling, for “darkroom work.” Sources on the Gowins include the author’s multiple interviews with Emmet and Edith Gowin; Emmett Gowin, Emmet Gowin: Photographs (1976, reprinted, Gottingen, Germany: Steidl, Pace/MacGill Gallery, 2009); Emmet Gowin: Photographs by Emmet Gowin (New York: Aperture, 2013); and Jonathan Green, ed., The Snap-Shot (Millerton, New York: Aperture, 1974); Sally Gall, “Emmet Gowin,” Bomb 58 (Winter, 1997): 21; and Merrell Noden, “Finding a Place: Emmet Gowin,” Princeton Alumni Weekly (October 21, 2009), https://paw.princeton.edu/article/finding-place-emmet-gowin, accessed December 9, 2018. Sometimes I use first names to distinguish Emmet and Edith.

- On the Civil Rights Movement in Danville, see Emma Edmonds, “Danville Civil Rights Demonstrations of 1963,” https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Danville_Civil_Rights_Demonstrations_of_1963#start_entry; the Danville Civil Rights Movement, part of the Virginia Center for Digital History’s Mapping Local Knowledge Project, http://www.vcdh.virginia.edu/cslk/danville/interviews.html; and SNCC, “Danville, Virginia,” a 1963 pamphlet available https://www.crmvet.org/docs/danville63.pdf, accessed December 9, 2018.

- Gowin, Emmet Gowin: Photographs, 7.

- Gowin, Emmet Gowin: Photographs, 19.

- The quote is from Emmet Gowin’s talk at an event called “Terrible Beauty” at the Morgan Library and Museum, New York, New York, on September 10, 2015. This event coincided with an exhibition called Hidden Likeness (May 22–September 20, 2015) that Gowin curated that paired his own work with works from the Morgan’s collection.

- Gowin, Emmet Gowin: Photographs, 43.

- The quote is from a wall text for Gowin, Hidden Likeness, Morgan Library.

- Gowin, Emmet Gowin: Photographs, 77.

- Some of the best-known images of working-class segregationists were taken by SNCC’s Danny Lyon. See Lyon, Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992).

- See the special issue “The Snapshot Aesthetic,” Aperture 19, no. 1 (1974), in which the editor Jonathan Green transforms “snapshot” from a negative to a positive attribute. The first photographer included in the issue is Gowin, 8–15.

- Walker Evans, “Store with false front, vicinity of Selma, Alabama,” 1936, LC-USF342- 001139-A [P&P] LOT 1604; and “Vicksburg Negros and Shop Fronts. Mississippi,” 1936, LC-USF342- 008074-A [P&P] LOT 1634, both in Farm Security Administration–Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. On FSA photography, see James Curtis, Mind’s Eye, Mind’s Truth: Farm Security Administration Photography Reconsidered (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1989); Nicholas Natanson, The Black Image in the New Deal: The Politics of FSA Photography (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1992); Edward Steichen, ed., The Bitter Years: 1935–1941 (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1962); John Raeburn, A Staggering Revolution: A Cultural History of Thirties Photography (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2006); and Scott L. Matthews, Capturing the South: Imagining America’s Most Documented Region (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018). On Evans, see Walker Evans, American Photographs (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1938); and Maria Morris Hamburg, et al., Walker Evans (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, in association with Princeton University Press, 2000). Before the advent of the FSA photography program, Doris Ulmann and other photographers, influenced by modernism’s interest in “folk culture” and traditional crafts understood as threatened by industrial production, began to make serious images in rural parts of the South, especially Appalachia. See John Jacob Niles, The Appalachian Photographs of Doris Ulmann (Highlands, NC: The Jargon Society, 1971); David Featherstone, Doris Ulmann: American Portraits (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1985); and Philip Walker Jacobs, The Life and Photography of Doris Ulmann (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2001).

- On Christenberry, see William Christenberry, Southern Photographs (Millerton, NY: Aperture, 1983); William Christenberry (New York: Aperture and Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2006), a comprehensive survey of his photographs along with accompanying essays, published in conjunction with his 2006 exhibition William Christenberry Photographs, 1961–2005 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum; and Kodachromes (New York: Aperture, 2010).

- On Christenberry’s life, in addition to the sources above, see Terry Gross’s 1997 interview with William Christenberry on the NPR program Fresh Air, http://freshairnpr.npr.libsynfusion.com/photographer-william-christenberry-country-singer-charlie-rich; “Oral history interview with William Christenberry, 2010 March 3–31,” Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-william-christenberry-15884#overview; and “Interview: William Christenberry,” lensculture, https://www.lensculture.com/articles/william-christenberry-william-christenberry, all accessed April 2, 2018. Walker Evans, Crossroads Store, Sprott, Alabama, 1935 or 1936, “Church Sprott, Alabama, 1936,” LC-USF342- 008158-A [P&P] LOT 1604; and “[Church, Southeastern U.S.],” [1936], LC-USF342- 008260-A [P&P], both in Farm Security Administration Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. James Agee and Walker Evans, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2001), photograph of the Sprott store, no title or page number, and quote, 35.

- William Christenberry, Red Building in Forest, Hale County, Alabama, 1983, Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/55172; and Green Warehouse, Newbern, Alabama (1973–2004), J. M. Cohen Family Foundation, https://www.jmcohen.com/artist/William_Christenberry/works/44/#!44, both accessed January 21, 2019.

- Christenberry interview with Gross.

- Christenberry interview with Gross.

- Mircea Eliade, The Myth of Eternal Return, Or, Cosmos and History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1971).

- Christenberry talks about his evolving installation “Klan Room Tableau” in his interview with Gross. I saw a version of this piece at the University of Virginia Art Museum (now the Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia) in 2007.

- Sally Mann, Immediate Family (New York: Aperture, 1992); and Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossings, eds. Sarah Greenough and Sarah Kennel (New York: Abrams, 2018), 111.

- Richard B. Woodward, “The Disturbing Photography of Sally Mann,” New York Times Magazine, September 27, 1992, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/19/magazine/the-disturbing-photography-of-sally-mann.html. Fallen Child, 1989 is included in Mann, Immediate Family, n.p. Nancy and Dwayne, Danville, Virginia, 1970, is included in Gowin, Emmet Gowin Photographs (New York: Knopf, 1976), 33.

- Woodward, “The Disturbing Photography of Sally Mann.” Over the years, Mann has attributed her son Emmett’s name to the photographer Emmet Gowin, a relative, and to Emmett Till.

- Sally Mann, Deep South (New York: Bulfinch Press, 2005) includes photographs from three bodies of work, Deep South, Last Measure, and Motherland. For early explorations of the use of these processes, see Jan Arnow, Handbook of Alternative Photographic Processes (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1982; and The Alternative Image: An Aesthetic and Technical Exploration of Nonconventional Photographic Printing Processes (Sheboygan, WI: John Michael Kohler Arts Center, 1983). Mann was one of many contemporary artists experimenting with this process in the 1990s. For the artist’s own account of her turn toward landscape and alternative processes, see Sally Mann, Hold Still: A Memoir with Photographs (New York: Little, Brown, 2015), 208–240, quote 224.

- See Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossing for the images included in and a series of essays produced for Mann’s 2018 exhibition at the National Gallery of Art.

- Greenough and Kennel, eds., Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossings, 115. Eudora Welty’s photograph “Ruins of Windsor/Port Gibson/1942,” is included in Eudora Welty, Eudora Welty Photographs (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1989), plate 119, n.p. Clarence John Laughlin’s most famous book, Ghosts Along the Mississippi: An Essay in the Poetic Interpretation of Louisiana’s Plantation Architecture, (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1948), does not include his shot of Windsor. “The Enigma” (1941) is http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/44563/clarence-john-laughlin-the-enigma-american-negative-1941-print-december-30-1953/.

- Greenough and Kennel, A Thousand Crossings, 123, 121. This paradoxical move—the evocation of African American history that reveals as well its opposite, a lack knowledge of African American history—is on display in Mann’s memoir Hold Still as well. There are interesting parallels here with William Faulkner’s conception of the racial politics of his works of literature like Go Down, Moses.

- Greenough and Kennel, A Thousand Crossings, 143, 155.

- Search for Walker Evans and churches on the Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs Online Catalog at http://www.loc.gov/pictures/ to see many of these photographs. Jack Delano, “Negro Church near Greensboro, AL, July 1941,” in FSA/OWI Collection, Library of Congress, LC-USF342-045073-A [P&P] LOT 1624, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017795461/, accessed April 1, 2018.

- See Welty’s images of black churches made in 1939 in Welty, Eudora Welty Photographs. Emmet Gowin shared with me photographs of black churches he made in Clover, VA, in 1963 and Richmond in 1965 that became part of his thesis show at RPI.

- On photographing churches, see Colleen McDannell, Picturing Faith: Photography and the Great Depression (New Haven: Yale University Press), 2004.

- These images are reproduced, along with Mann’s recent photographs of black men and older images of her daughter Virginia and her housekeeper and babysitter Virginia Carter, in Greenough and Kennel, A Thousand Crossings, 172–241.