This story first appeared in the 21c Fiction Issue (vol. 23, no. 3: Fall 2016).

I left Render early and hitched all morning. Five rides. Proselytizers and moralizers every one, each with a warning about the evils of hitchhiking, the evils of teenage girls out in the world alone, the evils of cigarette smoking and lipstick wearing. Each of them with a great big warning against going up to the work camp at the new Cornstalk Dam.

My last ride was with an egg salad-smelling woman who drove her Cutlass Ciera slow around the switchback curves. She wanted to know what I wanted to do up there anyhow.

“I’ve got to see somebody,” I said, concentrating on a scab on my wrist. I picked at the brown bump to see if it was dry enough to come off without bleeding too much.

“Honey, ain’t nobody up there right now, I don’t think,” the woman said. “I saw on TV where the governor said something about that accident. You heard about that poor boy, didn’t you?”

I yanked the scab off and flicked it onto the floorboard. A trail of blood dribbled down toward my elbow.

“You got a boyfriend working up there?”

“No,” I said, and dabbed the blood onto my jean skirt.

Out the window the Cornstalk Regional Dam service road curved off to the right. The woman pulled to the edge of the blacktop.

“They’re forever thinking they can control this place,” she said, pointing to the hillside of poplars and locusts. “Dam that river. Chop these mountains up into usable pieces.”

I unpeeled my sweaty legs from the vinyl seat.

“How you getting back to town?” the woman asked.

I shrugged and tugged on the handle.

“Honey, are you sure—”

I slammed the car door and waved bye, flashing my fingernails painted half-orange, half-pink, chewed all down to the quick.

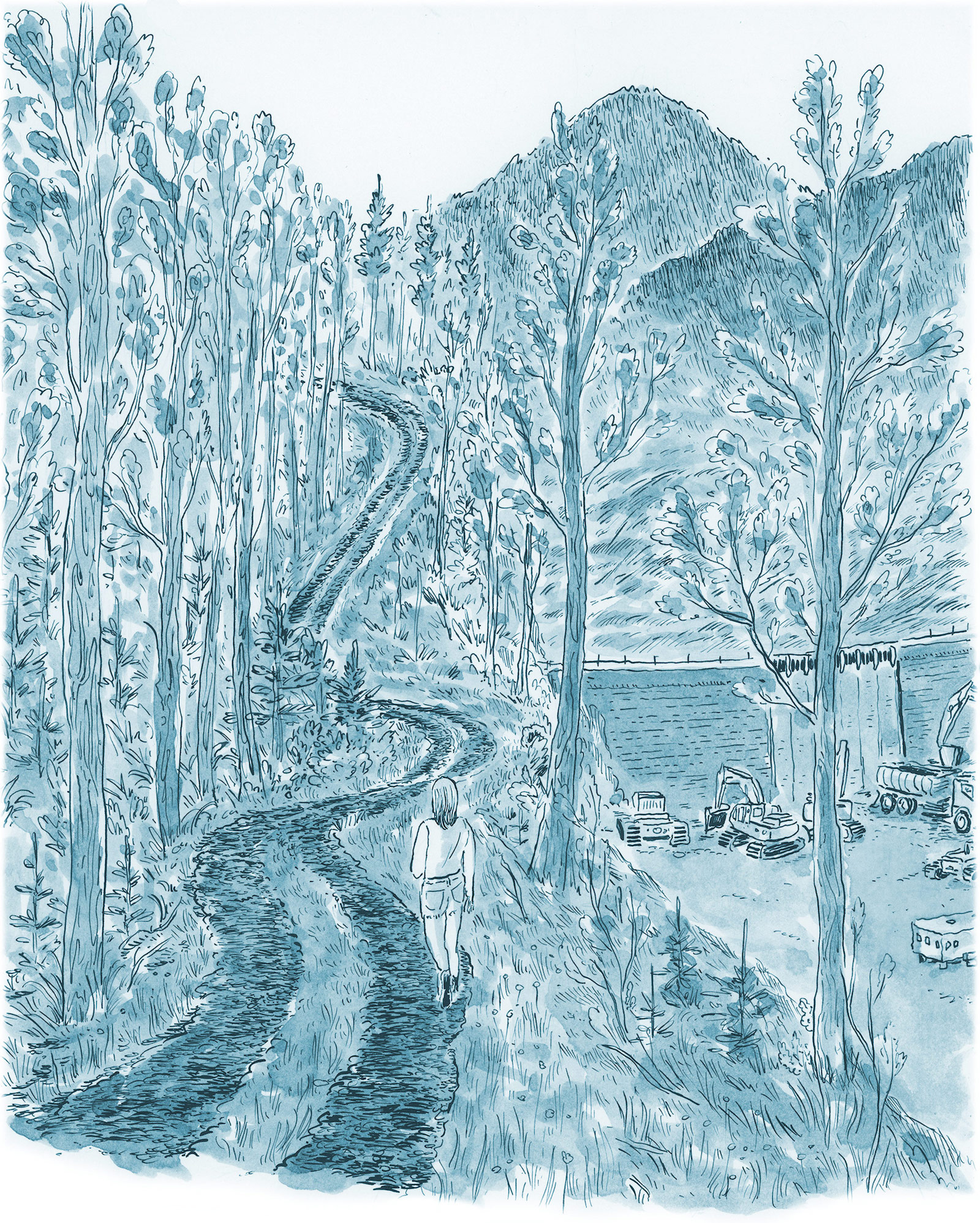

The Cutlass took off, leaving nothing but the whoosh of wind in the trees and a woodpecker tapping. I turned toward the service road and followed it up into the poplars, their leaves shivering in the breeze, covered with dust and curled into crinkled palms from the deep drought. The trunks of the ones along the edge of the road were splattered with shreds of paper and red paint.

‘They’re forever thinking they can control this place,’ she said, pointing to the hillside of poplars and locusts. ‘Dam that river. Chop these mountains up into usable pieces.’

In his first few letters, my brother, Blake, had written to me about how the protesters came here and stayed. They camped in the ditches with their signs about “Keep the Wild in Wild and Wonderful West Virginia” and “Dam You, No Government Control Over Our Rivers.” Blake said that when the boys came down from the work camp and into town on the weekends the protesters had crept out of the trees and hurled words and even stones sometimes. The workers threw back, especially on their way home from the bars. Empty Pabst bottles and pool hall darts, a dollar for every commie you hit. Pretty soon the protesters ran out of steam and slunk off. One Friday night the boys headed down to Diesel Dave’s and when they came up the last hill, the woods at the head of the road were quiet, spooky. They rolled down the windows and hollered at those goddamn pussy-whipped sons of communist bitches, but no sound came back except the peep of early tree frogs.

The woods were quiet now too and as I walked up over the hill the trees fell away and the Cornstalk Regional Dam rose in front of me. Amongst a jumble of raw earth and bent trees, the concrete walls spread smooth and clean. Half a dozen bulldozers and excavators were parked, frozen mid-dig at the base of the dam. And though the gray walls were as dry as a hot July road, they had a movement to them, a swooping glide where the white wave would someday topple over the cement crest. Even in all that dust-dry drought I swore I could hear the water thundering.

The road split, winding one way down to the dam and the other way off towards a huddle of tin trailers scattered about in a clearing of white pines. The trailers were empty, but as I came down the hill I imagined the boys at the windows, all the buddies Blake had talked about. I chewed on my thumbnail and shuffled my flip-flopped feet in the deep tire tracks, wondering how I looked out there against the brown hillside and the oversized Tonka trucks. The reflection that the full-length mirror in my mama’s bathroom threw back at me was nothing to get too excited about. A gangly, chigger-bit string bean. Hair too frizzy to do much with. Barely a whisper of tits below my cotton tank top.

The door to the first trailer hung open but no noise came from inside.

“Hello?” I called as I walked into the maze of tin buildings, past a drooping clothesline with one pair of stained boxer shorts and an orange bath towel.

A door slammed somewhere back towards the end of the camp, and I jumped and called out again.

The boy came around the edge of the trailer with a smile already tickling his lips. Built small, like Blake, but with brown curls and full, pink lips.

“Hey, girl.” He tipped his head back to finish the last drops of a can of Miller High Life. “What brings you out this way?”

I tried not to bite my nails but I couldn’t figure out what to do with my hands so I brought them to my mouth anyways and sucked on my knuckle.

“I’m . . .” I stuttered and swallowed. It felt funny trying to talk out loud about Blake. When the news had arrived, Mama had paraded her sadness like a brand new dress, but me, I’d curled mine into a ball and slipped it down my throat.

“Blake,” I said, “Blake Cole was my brother.”

The boy was staring at the ground when I said it, but he glanced up quick and didn’t look away. His eyes shone a soft blue.

“Shit,” he said. “I’m sorry. I mean, I ain’t sorry he’s your brother—” He turned and headed back towards the end of the camp. “You want a beer?”

“You knew him?” I stumbled, trying to catch up, chewing hard on my thumbnail again.

“Shit, knew him? Him and me and Jake shared the trailer. His bed’s still there right across the room from me, staring me in the eye like, ‘Hell, buddy, it could have been you.’”

I couldn’t tell if I hated this boy for his casual closeness to Blake or loved him for it. Blake never told me he missed me, but from the fact that he wrote me so much, I knew he must have. We were only four years apart and when I was little it hadn’t mattered much to me that Mama was never home or that the kids at school didn’t want me around after I had my head shaved for lice, because I had Blake. Had him all to myself till the summer he got a girlfriend. Then he was gone more evenings than not. He begged until Daddy broke down and let him use the car to take Monica Arbaugh out on drives. After he left, I would slip into his bedroom, sit in the corner where we used to build pillow forts and listen to the car tires out on the main road, the creaks of the house as it settled empty without him. When he pulled up in the yard, I ran back to my bed and lay there waiting to hear him come up the hall, whistling.

“Sorry about the mess,” the boy said, walking up the cinderblock steps to the trailer.

Inside it was stifling hot, full of yellow afternoon light through plastic blinds. Airless, like a sickbed slept in too long.

“Electricity got shut off when they put us on break, but I don’t have nowhere else to go right now.” The boy pulled the door to the fridge open and grabbed two cans. “I was keeping these babies cold down in the creek, but I got lazy.” He smiled a full lip smile, cracked a beer and handed it to me. Slightly cooler than the air around it.

I walked down to the end of the kitchen and into the bedroom Blake had shared with this boy. A pile of clothes and ripped magazines spread across the floor, one mattress was covered in rumpled blue sheets and the other one stripped bare. The company officials had mailed Blake’s belongings to Mama and Daddy after the accident. A humble little package with his wallet, two pairs of Dickies, three flannel shirts, and a letter he’d meant to mail to me. He’d written the letter the morning before he died, excited about the days to come when they were going to open the gates and bring the water from the diversion channels into the dredged riverbed. He joked about how the drought had stolen their thunder and no one would be very impressed with their work till flood season came in the spring.

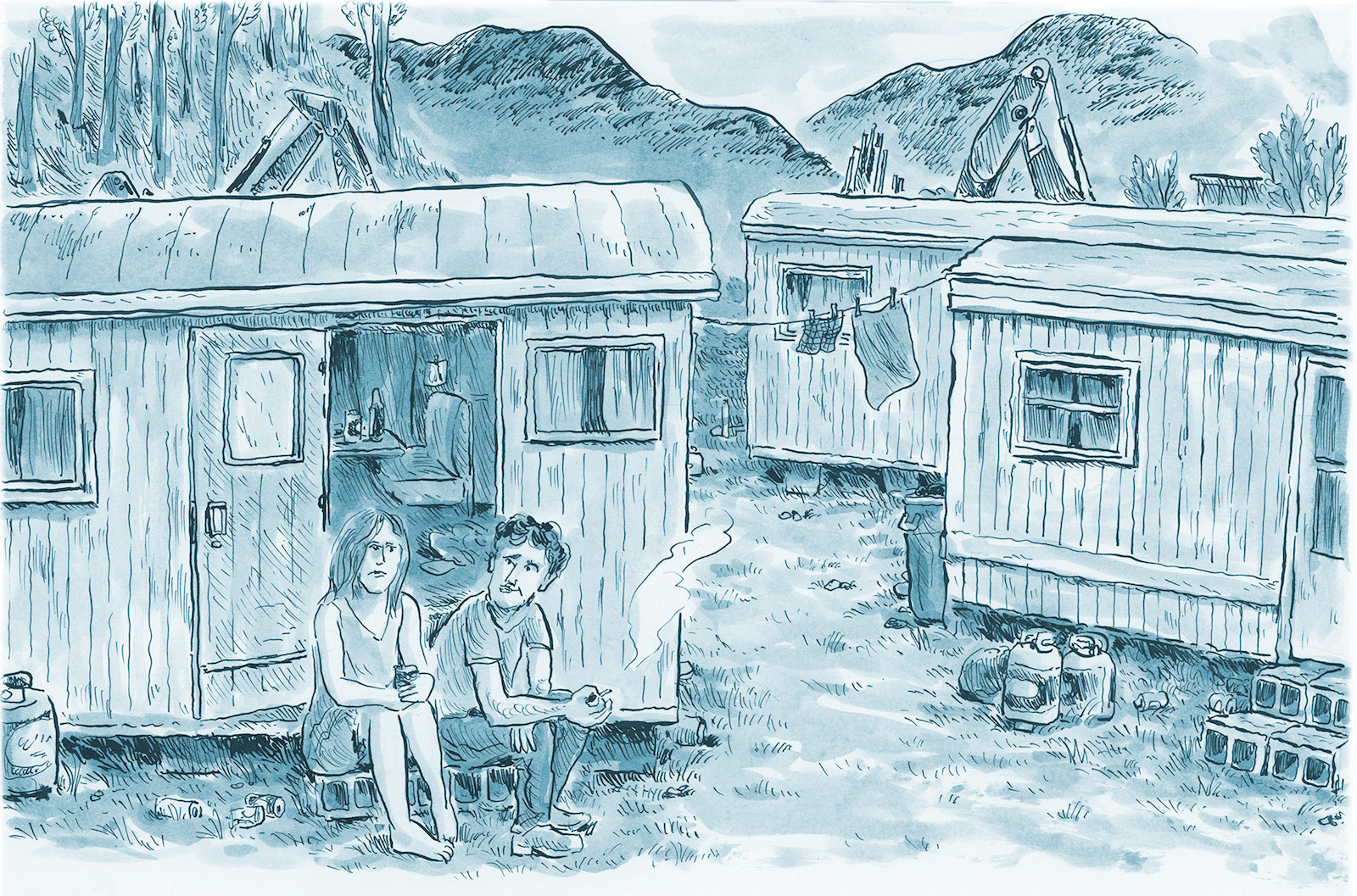

“Hey, come on out here, it’s too hot in there.” The boy sat down on the cinderblock steps. “I’m Billy Layner,” he said, “and you’re Charlene?”

“Charley.” I settled myself beside him and took a sip from the can of beer.

He nodded and pulled out a tiny hand-rolled cigarette. The damp stink of weed smoke filled the air between us. He held it out to me. I took a hit then passed it back and leaning against the steps, I closed my eyes and felt the wooziness and the wind blowing down off the mountain. This must have been what Blake did most evenings here.

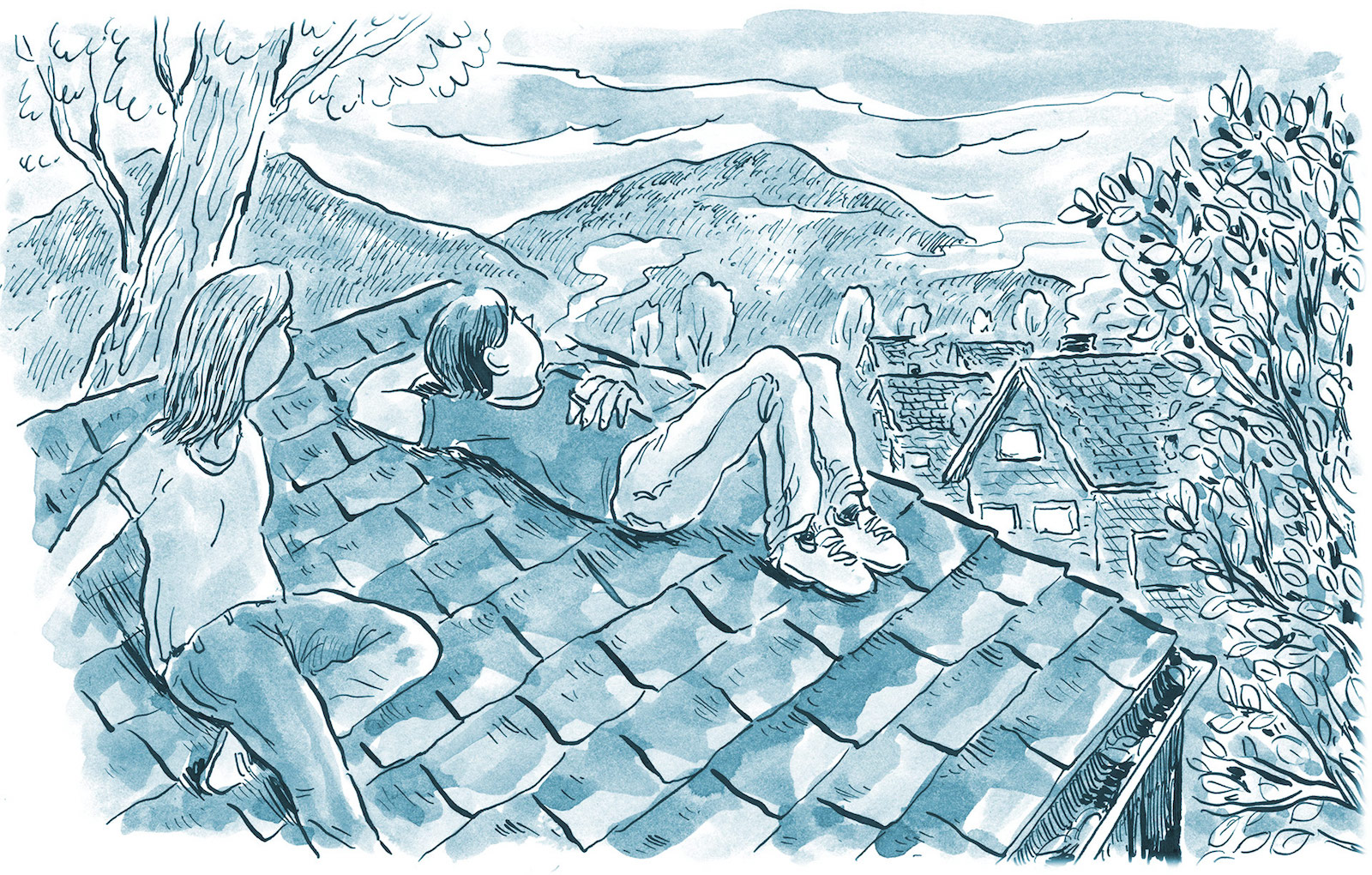

After I caught him smoking out on the roof last summer, Blake had shared his stash with me. In the evenings, once Mama and Daddy got settled in bed, we’d climb through Blake’s bedroom window and out onto the rough green shingles where we passed the joint back and forth until it burnt our fingertips. I’d talked too much and Blake had reached out, held his hand over my lips. His hair fell down across his forehead and his eyes had shone, crinkling at the corners as he smiled.

“Shush, calm down,” he said. “Feel that wind on your skin?”

He took his fingers from my mouth and what I’d felt was their absence. I wanted to reach out and touch him, but he stood up and walked to the edge of the roof.

“You feel that, Charley?”

The night breeze blew in from the river, carrying with it the sweet-sour scent of raspberries ripening and damp cut grass.

“I can’t believe this place.” Blake stretched his arms wide, the pale outline of his body silhouetted against the purple evening air and the black folds of Bethlehem Mountain. “I can’t imagine anywhere more perfect,” he said as he lay down on the roof. I watched him, laid out there, eyes closed, chest rising and falling, and I’d wanted that moment to stretch on forever, wanted my life to be one looped track of that instant there.

“You need another beer?” Billy stood up and headed inside.

I nodded and swallowed the last of my can.

“Charley, I heard all about you,” he said as he came back out the door, passing me a fresh beer. “Blake was always talking about you.”

Blood tingled in my face. I lifted the can up and took in a big mouthful of warm beer.

“Look at you blushing.” Billy laughed. “You and Blake was weird like that, huh?”

I tried to swallow the beer but my throat closed up, so I held it in my cheeks and let it leak down slow. “Weird like what?” I edged the fingers of my left hand under my butt so I wouldn’t chew them.

“You know what I’m talking about.” He smiled. “I ain’t saying y’all did anything, just saying you were real close, seems like you must have looked at each other that way sometimes.”

Billy tilted his head for a drink and I watched the way he moved, confident, smiling like he knew things about me that I couldn’t even put into words. Rage rose up over my slow, dumb sadness. I reached my arm back and threw my nearly full Miller can straight at his face. It hit with a thunk. He squawked and I leapt up from the steps and took off behind the trailer. I ran past tipped-over trashcans and abandoned gas cylinders, kept going until I hit the edge of an embankment that tumbled down into an empty channel. The water was all gone but the current was still visible in the swirled patterns of sticks and leaves.

I hadn’t cried when we got the news, or at the funeral, but the feeling of it had stuck right there in my throat, gave me the sensation that I was all the time moving underwater. The house had filled with Mama’s kin and the ladies she worked with over at the Riverside Café. Their dumpy kids settled down in front of the TV, kicking each other and picking pimples. The ladies brought casseroles, cornbread, cobbler, and fried chicken. Their dishes covered every inch of the counter and in the lulls between conversations they took turns organizing and reorganizing the fridge. They crowded close to Mama, refilling her glass of tea, cigarette smoke a blue haze, knitting needles clacking. Their voices ran constant, up and down, the Lord shall provide.

Norfolk Southern had found someone to temporarily take over the trains Daddy usually drove out of Clifton Forge. When I passed him in the hallway he touched my face and smiled. He stood for long minutes in the doorway to the living room, watching Mama and her ladies watch the TV, but most of the time he stayed in the bedroom, radio playing Johnny Cash and the sweet smoke from his pipe curling out from under the door.

I had avoided everyone. I lay on the foam mattress in Blake’s bedroom and counted the squares in the moldy ceiling. Sixty-five. I counted them over and over again. In the front room the voices pitched high.

“Oh, Trisha,” Mama’s ladies said, “Trisha, I can’t even imagine how you must feel.”

“No, no, honey,” Mama responded. “I hope you never know how it feels.”

I couldn’t feel enough. I pinched my arms. Counted the squares again, felt nothing. I cut into my wrists, drawing intricate blood bracelets with the razors I found in Blake’s top dresser drawer, but the pain felt like nothing more than the scratches Blake and I got from picking blackberries up on Bethlehem Mountain.

I found a pack of Marlboros, wedged between the bed and the wall, and I smoked slow, crushing them out into the bottom of a jelly jar when they were half gone, to revisit them later. The smoke made my head spin but other than that I still felt nothing. I lay on the carpet between Blake’s bed and his dresser for so long that my legs fell asleep and when the need to pee overcame me, I let it slip out warm through my shorts. I’d tried to care that I was fourteen years old laying on the floor in my own piss but none of it felt real and eventually I fell asleep.

“Hey, Charley.” Billy climbed down into the dry channel behind me.

I could have run but my chest had drawn tight again and I didn’t much care if Billy was angry. He stood so close I could hear him breathe. I braced my body for the blow but when he touched me it was soft, firm hands on my bony shoulders, hugging me close. He smelled of sweat and weed smoke. I leaned into him and closed my eyes as he ran his hands across my stomach and up my chest, his callused fingers catching against the thin cotton fabric. My nipples hardened under his touch and I shivered despite the heat.

“Take me to the river,” I said.

Billy lifted his hands off me and stepped away.

When I spun around to face him I saw the shadow of a new bruise across his cheek and brought my hand up to it. “I want to see the river,” I repeated.

He brushed my hand off his face and kicked at the dirt with the toe of his boot. “There ain’t no river right now.”

“Fine,” I said, “then take me to the channel.”

He looked up at me. “Your brother drowned in that channel.”

I nodded.

“I ain’t taking you down there.”

“I’ll find it myself.” I walked past him, but Billy grabbed my hand.

“When I was twelve,” he said, “my daddy died, over at the Frazier mine.”

I glanced away across the bare ground. I hated it when people pulled out their own sorrows and laid them there like maybe more sadness would make everything okay. I freed my hand from his and walked on, but Billy moved ahead of me before I’d taken two steps.

He walked all easy through the strange, torn-up landscape. I liked the look of him out there and I was tired of not liking the look of anything. When the breeze blew through my shirt I remembered the brush of his hands on my nipples. Above us, the dam leaned like a row of smooth, carved teeth. Billy stepped off the road and headed out amongst the pine stumps. I hung back; craned my neck and squinted up at the high walls of the dam. I felt the weight of it pressing against the hot blue sky, the crush of cement pushing the mountains apart.

I don’t give a flying fuck about those commie protesters and all their reasons against this dam, Blake had written to me, but there’s this thing the old timers down at Diesel Dave’s are always saying and it gives me the creeps. They’re forever talking about the Curse of Cornstalk and how we shouldn’t go around naming the dam after that poor backstabbed injun, cause his blood was bad, turned this land sour when he died. They tell stories about our reservoir in Render too, how before the government filled it with water, Skinner’s Valley was the prettiest place around.

“Here you go, here’s your river.” Billy waved his hand as we reached the edge of the clearing where the ground dropped down.

Blake had told me how the Sipsipica River had been diverted when they first began construction, shunted out of its banks and into side channels so that the riverbed could be cleared of silt and sediment. In the channel, the water was a thick red-brown, smooth as if unmoving, the current only visible along the edges where branches broke the surface.

I kicked my flip-flops off and climbed down the dusty bank.

“That ain’t good swimming water,” Billy called.

“No shit.”

As I reached the water’s edge, the air grew cooler. I squatted down, closed my eyes, and pictured Blake waiting there at the end of the channel, hand on the lever, waiting for the signal to raise the gate, waiting as the wall of water leapt up and crashed over him, sluiced on down, down, down, gravity-drunk.

I glanced over my shoulder and squinted up the bank at Billy. Dirty white t-shirt, brown curls shining in the sun. I could still feel his hands on my skin. This man, who for his slight build and loose charm could have been my brother or my brother’s twin, this man who could have been the one to die.

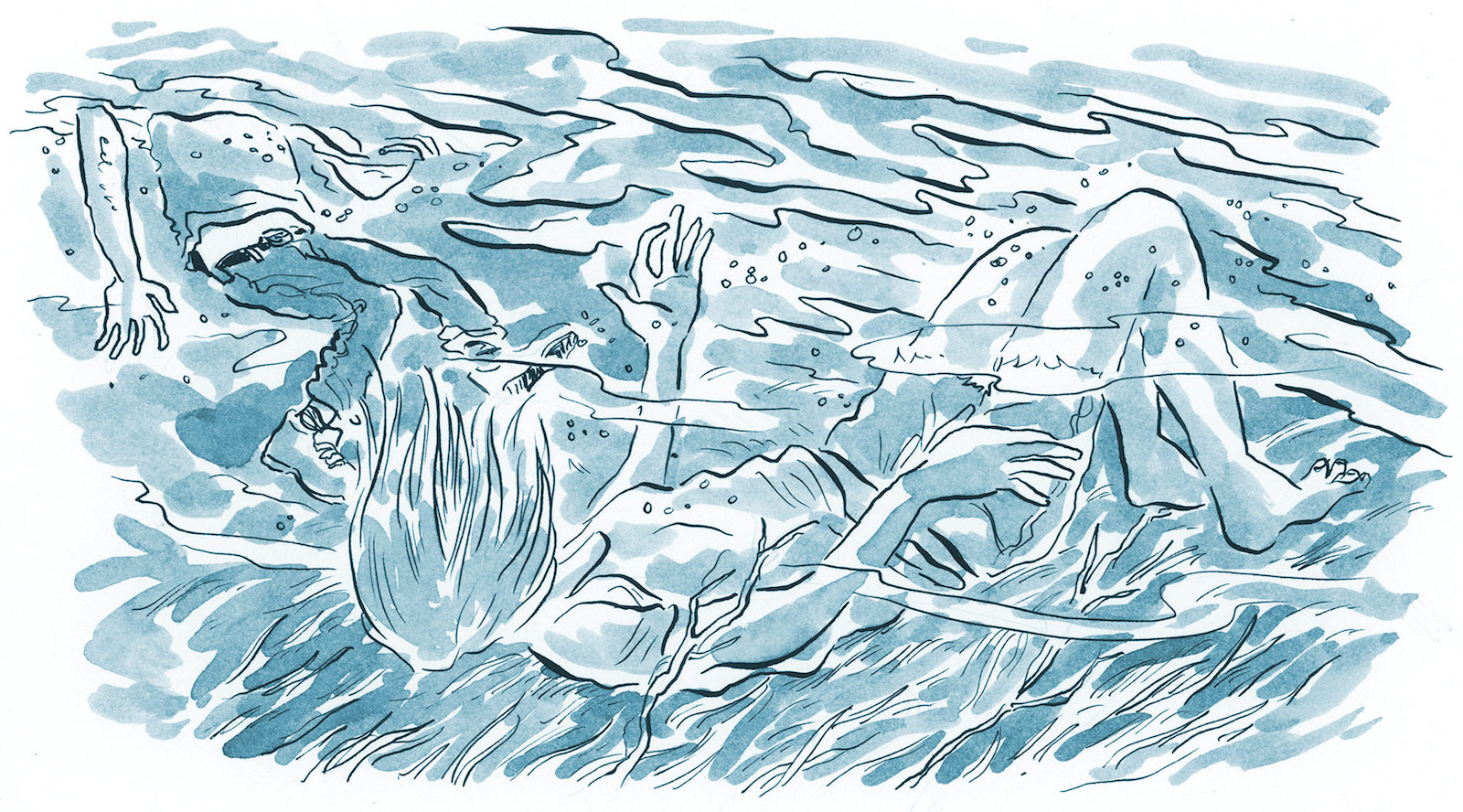

I bent and dangled my hands in the channel. You feel that, Charley? The water was colder than I expected, stinging my half-healed wrists. Tipping forward and back on the edge of the bank, I felt the pull of the current. That water that whispered its own name. Sipsipica. Sipsipica. This was the ditch Blake had dug, the last place where he lived: these trees, this air, the red-orange mud squishing between my toes, glittering with chips of mica. I reached deeper into the water, leaned out, and let myself tumble into the brown surge.

The shock of the wet slapped my face and water gushed up my nose and mouth. My body arched. I stretched my fingers and toes wide, clawed and grasped but the current kept me down and pulled me towards the floodgate. Rocks and sand and sun through mud-thick water. I hadn’t known what it was that I’d wanted when I pitched myself into that stream, but now I had it: nothingness. I was not a sister, daughter, friend. I did not feel loneliness, just my heartbeat throbbing in my head and my chest tightening. I blinked my eyes open and closed, searching for top or bottom, but it all got jumbled up.

The current flipped me and I surfaced, choking in a mouthful of silt water. Above me Billy ran along the bank, hollering my name. The world was so bright, the trees behind him green beyond green and the sun bleaching hot. I still did not know what I wanted but my body, all on its own, was determined to reach land. It kicked, flailed, and pitched against the water and when I got to the edge, Billy bent, frantic to help. I caught hold of his hand, strong and dry, but he shifted then and as I leapt up, he came splashing into the water on top of me.

We streamed down together. I let go of Billy’s arm and pushed away but his legs tangled around me. In the dark water we struggled, lungs screaming, hands reaching out for anything, until finally, weak and breathless, I quit moving. There was nothing but the push of the current, all one way now without the struggling.

I was timeless, weightless, there in the heavy holding-me of the river full against my skin until something brushed my fingers—roots first, then leafless limbs and I heaved to the surface again. The light was shattering, the water lapping as I pulled my wet weight up onto the safety of the red clay bank.

On his own Billy floated easier. Grabbing a low branch, he bobbed and inched his way to shore. I vomited up a pool of mud-water and lay down, my wet clothes sticking to my back, head spinning like a million sparkling kaleidoscopes. As Billy crawled up the bank, I watched him and all those days of no crying, no talking, shook up inside me like a bad cough and came out as laughter. I sat up, laughing. Billy squeezed the water out of his hair and stripped his t-shirt off.

“You’re fucked up, girlie,” he said, but he didn’t sound angry, just tired and confused.

He pulled his legs out of his muddy boots and grimy pants, turning away from me as he stripped naked. I smiled at his modesty. Without his clothes on, he looked more muscled, like a larger man who’d been compressed somehow, a small workhorse. He wrung his jeans out, splashing the water onto the orange clay, then tugged them back on.

“Fucking crazy.” He shook his head again and sat down beside me.

The sun threw hazy shade across our bodies. Under the wet fabric of my tank top, my tits looked much larger than they did at home in my bathtub. I wondered if Billy had noticed, but he was tracing my hand with his fingers, pausing at my scabbed wrist. When he glanced up at me, I turned my face. He rested his head against my hip and closed his eyes. In the trees the cicadas droned, a cyclical call that built and ebbed. I stared down at Billy’s face, laid my hand against his breastbone and felt the calm there. I moved my hand to my own chest, leveled my breath and matched it to his, in and out, under my ribs, simple and strong as bedrock.

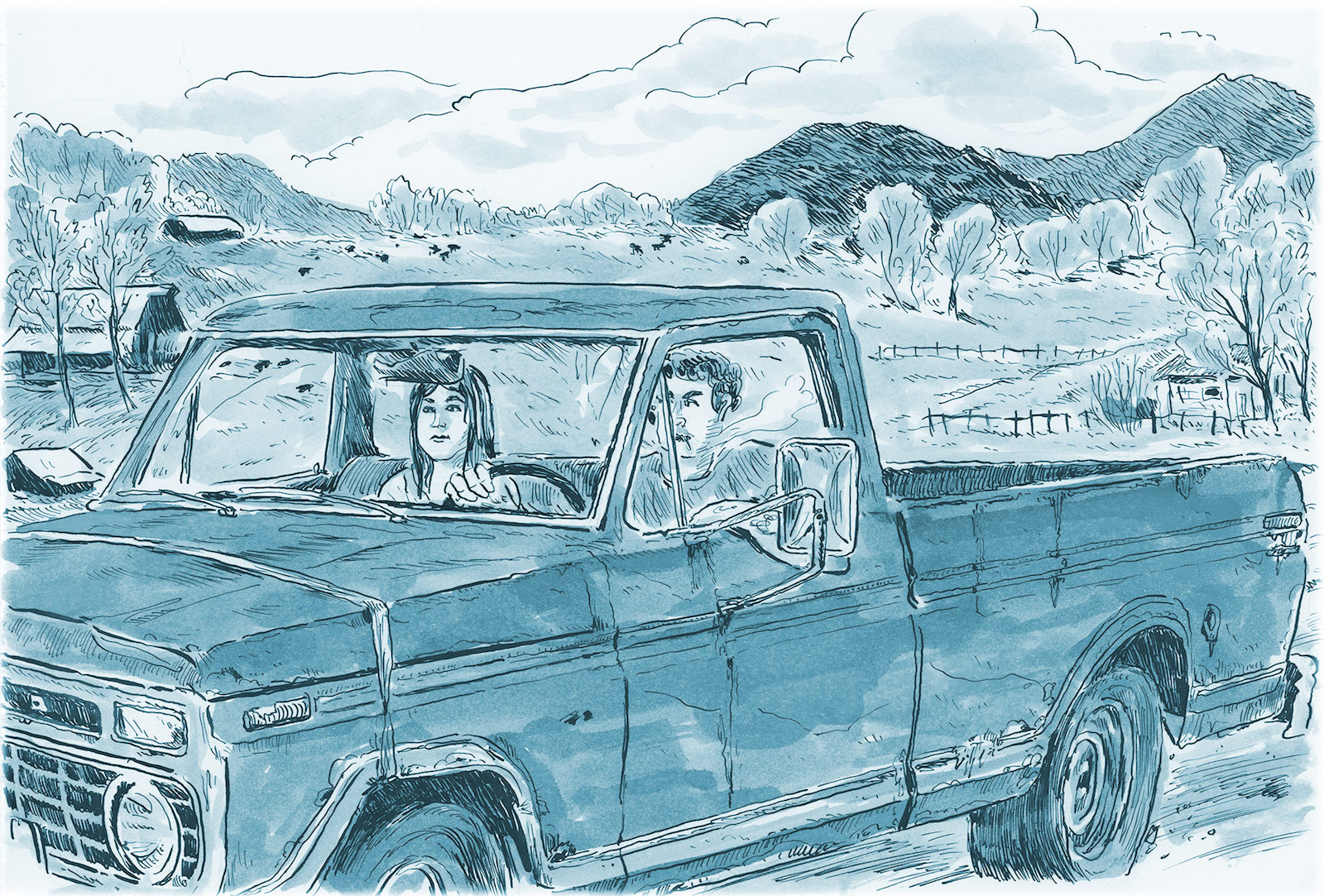

Billy drove me home in a pickup truck with a baseball-sized hole in the floorboard. I situated my feet far away from the hole and watched the dam grow small in the dirt-streaked rear windshield. The mountain peaks pressed down on the cement walls from each side until it looked like nothing more than a scab, a tiny imperfection in the ancient chain.

The water from my hair dripped all down my back and gathered in a pool at my tailbone. Billy drove with his window down, cigarette clenched between his teeth.

“You doing alright?” he asked.

“Yeah, I’m good.” I nodded.

He bent to retrieve his lighter and I felt the heat of his body against my legs. Out the window, the drought-dry fields sped by, splotchy cattle crowded together in the shade, wading up to their knees in scum-green ponds. Brown-eyed Susans grew in clumps beside mailboxes, petals curled around their stubby centers, leaves stiff and burnt.

When we pulled up outside my house, the driveway was empty. Not a single cousin’s Oldsmobile or coworker’s Chevy. I had thought I’d feel relieved when they were gone, but all the emptiness seemed sad now.

“You think your mama’s home?” Billy asked.

I nodded and climbed down, the hot asphalt soft under my flip-flops.

“I’ll see you,” I said, turning away.

“Hey,” Billy said, “I’m gonna try to come down and visit, maybe even before the job’s done if they give us a day off.”

I squinted against the bright sun, smiled and pushed the truck door closed.

I knew that he’d wait there till I got inside and the knowledge of it curled warm in my gut as I walked up the drive. From the porch I could hear Mama’s radio, playing her spiritual songs . . . I’m going there to see my mother, she said she’d meet me on that shore, I’m only going over Jordan, I’m only going over home . . .

I pulled open the screen and stood in the doorway, blinking against the cool darkness of the kitchen, the yellow heat of the day still clinging to my back. As my eyes adjusted I saw Mama standing at the counter, turned away from me, radio on so loud she hadn’t heard my arrival yet. The kitchen counters were cleared of all the covered dishes and Mama stood alone beside the sink, chopping potatoes and dumping them into a silver-handled pot.

She wore her work clothes, a white smock of a dress with a red collar. The other waitresses down at the Riverside Café had taken over her shifts for the past two weeks, pooled tips to give to her and kept her up on the gossip, but I guessed the break had to end eventually. Mama lifted one leg and flexed the foot. Her calves were swollen with purple veins like thick tributaries from the hem of her skirt down to her ankles. I could feel how her feet must ache from the hours at work and the long walk home. I’m going there to see my Savior, the radio sang, he said he’d meet me on that shore.

Without looking, I knew that Billy was still waiting at the end of the drive.

“Here,” I said, stepping up beside Mama. “Let me see that knife.”

This story first appeared in the 21c Fiction issue (vol. 23, no. 3: Fall 2016).

Mesha Maren’s short stories and essays have appeared in Tin House, Oxford American, Hobart, The Barcelona Review, Forty Stories: New Writing from Harper Perennial, and other literary journals. She was chosen by Lee Smith as winner of the 2015 Thomas Wolfe Fiction Prize and is the recipient of a 2014 Elizabeth George Foundation Grant, an Appalachian Writing Fellowship from Lincoln Memorial University, and residency fellowships from the MacDowell Colony, the Ucross Foundation, and the Vermont Studio Center. Her debut novel, Sugar Run, was published by Algonquin Books earlier this year.