In her series (Untitled) Kitchen Table (1990), photographer Carrie Mae Weems explores and questions perceived notions of racial and racially gendered identity, using the familiar, everyday experience of a woman seated at a domestic kitchen table. Alternating between images of herself alone and with a male lover, child, or with other women, she figures the kitchen table as an architectural space within which to present ideas about tradition, family, monogamy, and relationships. The beautiful, clear-eyed, and complex images in this series established Weems as a photographer politically engaged in critiques of how power is expressed in social space. Yet, Weems has received little attention, to date, for how her photographs of architecture—including antebellum plantation houses (the Louisiana Project, 2003), classical buildings in Rome (Roaming, 2006), and dwelling structures in western Africa (Africa, 1993)—comment on racial subjectivity. In the Louisiana Project, Weems highlights the potential of buildings and landscapes to engage discourses of power, identity, gender, and race. By emphasizing architectural space, Weems’s black-and-white photographs in the Louisiana Project reveal how architectural and preservation practices emerge from and, in turn, influence cultural beliefs about identity and race.

Weems undertook the Louisiana Project in response to an invitation from Tulane University’s Newcomb Art Gallery and New Orleans officials to contribute to the city’s bicentennial commemoration of the Louisiana Purchase (1803), which marked a critical moment in North American history. It added well over eight hundred thousand square miles of territory to the United States, while also assuring an aggressive push westward that resulted in the deaths of thousands of Native Americans, the near destruction of many aspects of Indigenous life and culture, and effectively extended the practice of enslavement into new territories. For her contribution to the bicentennial, Weems identified architecture as a critical component in shaping African American cultural identity. In her photographs, she used her own figure to bear witness, standing as a vivid, living symbol for the cultural history of colonization and its continuing impact on Black communities. Clothed in period costume, Weems’s figure is spectral and suggests the force of cultural haunting. For Weems, history inheres in architectural forms and in the bodies of living human beings who descend from and inherit the as yet unresolved terms of settler colonialism. The Louisiana Project juxtaposes antebellum buildings that have been kept pristine into the twenty-first century with industrial spaces—landscapes scarred by rusting gas tanks, railroads, and mass-produced housing for impoverished and African American residents. Her photographs transform our way of seeing, challenging conventions of architectural photography by inserting her own body as witness figure. She observes these architectures from the implied perspective of a ghost, her gaze a critique of longstanding structures of racism.

Dressed in nineteenth-century calico garb, Weems presents herself in A Distant View seated in the lengthy shadow of a large tree, the leafy canopy of which frames a view of an antebellum mansion. The photograph’s formal composition, with its soft focus and shadowy framing, emphasizes the stark white forms of an elegant building set against a lush landscape and bright sky. In view is the René Beauregard House, so named for its later owner—a high court judge and son of prominent Confederate army officer Pierre Gustave Tourant Beauregard. Situated on the banks of the Mississippi River two miles south of New Orleans, the house was originally designed in the French Colonial style around 1832 and remodeled by architect James Gallier Sr. in the late 1950s.1

The structure included elaborate, decorative trappings of classical Greek architecture with eight double-height Doric columns forming front and rear galleries that lent expanded space and height to the body of the building. There were four symmetrically placed double-height French windows with fine details, such as pedimented dormers and a decorative entablature connecting columns to a steeply pitched roof. This classical architectural vocabulary served to advertise what the patrons considered their rightful place in the crucible of civilization: ancient Greece. The popular Greek Revival style, combined with the choice of architect (Gallier went on to design the much-admired New Orleans City Hall), symbolized the taste, sophistication, and social status to which Louisiana’s antebellum elite aspired. To sustain this ambition, large numbers of enslaved people toiled in households and distant fields. These individuals lived in separate quarters or in the lofts of outbuildings like kitchens and washhouses. Whether laboring indoors or out, enslaved people remained unseen by white landowners, but as folklorist John Michael Vlach has asserted, “Beyond the white master’s residence, back of and beyond the Big House, was a world of work dominated by Black people. The inhabitants of this world knew it intimately and they gave to it, by thought and deed, their own definition of place.”2

In a caption, Weems gives one of these unseen, unheard women a voice:

I was not amongst the gentle crowd of ragged negroes gathered together in the evening to stand under the old oak tree and sing sad spirituals, while the gentleman of the house and his guests reflected with glee, the naturalness of their privilege. No, I was the chambermaid, the whore and the witness.

Employing a timer to create the Louisiana Project photos, Weems directs her view toward buildings and landscapes, away from viewers, so that we see her back in every image and, rarely, a trace of her profile. Seldom does Weems turn to face us. In posing as a silent observer engaging with the cultural landscape before her, she characterizes this environment as something that must be faced. This stance implicates the audience. As photographer Deborah Willis notes, Weems’s use of her own figure in her photographs doubles the gaze implied in the image: as she witnesses, we are also privy to the relationship of this figure to the buildings and landscapes before which she stands. The witness figure testifies to the presence of enslaved African Americans in those historic antebellum scenes, forcing a consideration of the built environment through her eyes. By positioning her body in this way and wearing nineteenth-century clothing, Weems appears as a ghostly survivor of enslavement.3

In Passageway II, Weems photographs herself framed by the columns of the Beauregard House, looking out to the landscape beyond. She suggests that the viewer reflect on the position of Black bodies in antebellum Louisiana, framed within the architecture yet within sight of a horizon unconstrained by built forms. The figure’s back is turned and her body is centered in the structure’s heavy-columned frame. The deceptively beautiful neoclassical columns of the Old South impose a heavy weight upon African Americans yearning for the unburdened, liberated horizon. In contrast to the frame’s depth and darkness, the plantation beyond it appears vast, a domain of colonized space that holds tragic histories. Weems, the observer, remains steady, her gaze directed determinedly outward, unerring. The photograph suggests a passage through this architecture and a way beyond its oppressive historical constraints to the hopeful possibilities of northern cities where Black people could imagine living as free people.

When Weems photographs herself standing before antebellum mansions around New Orleans, she confronts architecture built with the white supremacist dream of oppressing Blackness—oppressing knowledge of Africa, and African forms, languages, and culture. Constructed as a French port city, and briefly managed by the Spanish monarchy, the city expanded its identity with the Louisiana Purchase to become increasingly diverse demographically, economically, and culturally. During the early years of settlement, the French established a unique but nevertheless exploitative caste (or plaçage) system, legally recognizing the “mistress” relationship between a white man and a woman of African descent. These women and the descendants of their unions were classified as mixed-race, creating a third caste, or group known as gens de couleur, or free people of color, who, because of their acknowledged familial relationship to the dominant white class, complicated the racialized landscape, laying claim to privileges and social activities unique to New Orleans, such as annual Mardi Gras balls. Although free women of color were granted some recognition as the bearers of white French or Spanish settler children, they were never fully accepted into the ruling class nor did they identify with the enslaved people of color. Excluded from the true world of white privilege, and self-segregated from the enslaved community, this mixed-race group of free people of color made its own spaces of relative freedom that were nevertheless separate.4

Weems seems to refer to the women of this third caste in a triptych of images, A Single’s Waltz in Time. Framed within the luxurious interior space of another plantation mansion and once again dressed in calico, Weems dances barefoot with mournful grace. For once, she faces the viewer, then spins around, defiantly commanding the room, and intensifies this gesture of claiming the space by capturing it in the lens of her camera. The parlor was a fraught area in traditional southern society. It bespoke class privilege and was the particular site wherein white women demonstrated their social power over Black bodies.

A ghost figure dances through the parlor at Nottoway Plantation. The mansion was built for the Virginia-born sugar planter John Hampden Randolph, an interloper who installed himself among the wealthiest of New Orleans, intent, after the Louisiana Purchase, on forging a new American identity in the formerly French colonial landscape. In 1857, Randolph engaged Henry Howard, an Irish craftsman who apprenticed with architecture firms in New York and New Orleans to become a leading local architect (and, as such, exemplary of how white labor functioned in the plantation economy). Howard partnered with another immigrant, Albert Diettel, a German mason and engineer, who also worked his way from New York to New Orleans. The two made drawings and plans according to Randolph’s specifications, resulting in a massively proportioned Greek-Revival-Italianate design to compete with John Andrews’s neighboring mansion Belle Grove, completed that same year. Randolph’s highly ornate double parlor, known as “the ballroom,” staged debutante dances and served as the venue for the weddings of his five daughters.5

Is Weems’s barefoot, dancing form the unacknowledged Black Creole mistress, the “chambermaid, the whore” of A Distant View, who now stakes her claim to a place within the house? Here, Weems is suggesting the subtle and not-so-subtle social bondage of the systems of plaçage and enslavement. The “chambermaid, the whore” is specifically she who, by dint of race and class, cannot have social privilege in the public domestic sphere of the parlor. Her exclusion from this social space is made tangible by a structure emphasizing the white supremacist vision of so-called Western cultural superiority. These are architectural spaces of grief where women of African descent inhabit a realm entrapped within the white cultural dream of a life free from toil and care. Wealthy white women do not labor in parlors; they preside. The parlor signifies heavily in southern cultural practices where young white women were celebrated, and introduced to their peers and potential suitors, for example. The parlor is the space of utmost entertainment, where white families showed their wealth and dominion in a space they in fact shared with laboring Black enslaved people. Weems’s period garment places her in the realm of the woman of African descent whose body is constrained and unfree in white-dominated architectural spaces. Her witness figure here portrays both the enslaved woman of African descent and the Creole mistress.6

The dance, in this triptych, is a mournful declaration of freedom, the freedom of a Black female body to move to its own rhythm and desire, to lay claim to the space of the parlor that is a showpiece of white supremacy. The figure in the mantel painting, its head occluded by the sumptuous chandelier, stands blindly. And though that figure cannot see Weems’s dance, Weems nonetheless commandeers the hearth space in the sight line of the camera. The high ceilings and ornate molding convey the building’s impassive neoclassical aesthetic in contrast to the dancer’s expressive posture.

In further photographs, Weems compares the antebellum architectures pristinely preserved in twenty-first-century New Orleans with constructions from other periods in the city’s history. In In the Abyss, she faces a housing project built in the late 1930s as a federally funded response to homelessness and unsanitary Depression-era living conditions. These low-rise brick superblocks were initially intended for whites but were opened up to African Americans after passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The hope they signaled for better accommodation dissolved rapidly into the racialized categories of segregation, discrimination, poverty, crime, and neglect, disenfranchising and trapping African Americans once again.7

In the Abyss depicts Weems as the enigmatic nineteenth-century spectral figure engaging this building head on. Its three-storied brick facade towers above her. Folding chairs, a small BBQ grill, and other material artifacts of a hot and humid quotidian South spill out and clutter the narrow, shared balcony that runs the length of the building. The housing project fills the frame of vision so that we, the audience, see no escape from the abyss. The Louisiana Project photographs work by implicit comparison, as Weems shows antebellum mansions and contrasting hardscrabble industrial neighborhoods. In the Abyss stands in stark contrast to Weems’s photograph of the Beauregard House, which is shown in its totality with sky and lawn and trees softly framing the image, emphasizing the totalizing effect of white supremacy. The housing project, strikingly, is fragmented, cut off and tightly contained by the photograph’s frame. Laid bare in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, the city’s quarters reveal racist social patterns wherein substandard housing in predominantly Black neighborhoods, impacted by decades of redlining, was exceedingly vulnerable to devastation.8

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Standing on the Tracks), 2003. Gelatin silver print, 20 × 20 in. Photograph from the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. © Carrie Mae Weems; Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Woman Facing Industrial Landscape), 2003. Gelatin silver print, 20 × 20 in. Photograph from the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. © Carrie Mae Weems.

In one untitled photograph, Weems looks down the length of a railroad line. In another, she faces a sign painted on the edge of a building that advertises alcoholic beverages, a solution often sought to alleviate the despair and demoralization of those trapped in a cycle of unemployment and few resources. Both images connect to a broader history of segregation, longing, rootlessness, and despondency. The African diaspora created a people in constant motion, as enslaved labor shifted across antebellum plantation landscapes and as people sought freedom and opportunity after (and sometimes during) enslavement. Many people of African descent in the Americas would eventually join northbound trains to more hopeful, yet always uncertain, places, where they were often met with forms of structural racism promulgated beyond the traditional South.

Weems’s photographs depict a cultural landscape, dominated by white supremacy, that has denigrated African Americans, excluding visual clues of their positive contributions and reducing them to stereotypes, a situation that shockingly persists even where communities of color predominate. The architectures of white supremacy create ghettoization. When Weems includes herself in images of architecture, she creates tableaux that tell more complete and deeply troubling stories. Putting woman front and center as director of the gaze disrupts long-held and accepted narratives. In a recent interview about her work, Weems acknowledged her drive to be “a critically engaged woman” rather than the “social activist” she is often considered. Consistently using her own female Black body, Weems draws on James Baldwin’s stance that the artist’s job is to illuminate, insisting on this demystifying gaze from a woman’s perspective. In reenvisioning the habitation of architectural spaces that were built to hold hierarchy in place, she subversively reinserts her body as a critical tool to pose the deep question of “who we are as humans” and for Weems the artist, this always begins with herself as a moral force up against the dominating power in whatever form it may take, expressed here in the surrounding structures. As architectural critic Sarah Williams Goldhagen argues, “A change in a visual axis, or spatial sequence, or the way solids are massed and volumes composed could ignite very different cognitions.” In challenging the hierarchical force of the architectures of white supremacy, Weems opens not only new ways but also new visual spaces for seeing. Through her witnessing gaze, the oppressive history of New Orleans’s built environment is revealed and also revitalized as social space ripe for negotiation. She makes a claim on that space as a Black woman artist—a claim that extends through the Louisiana Project‘s image field to all people of the African diaspora.9

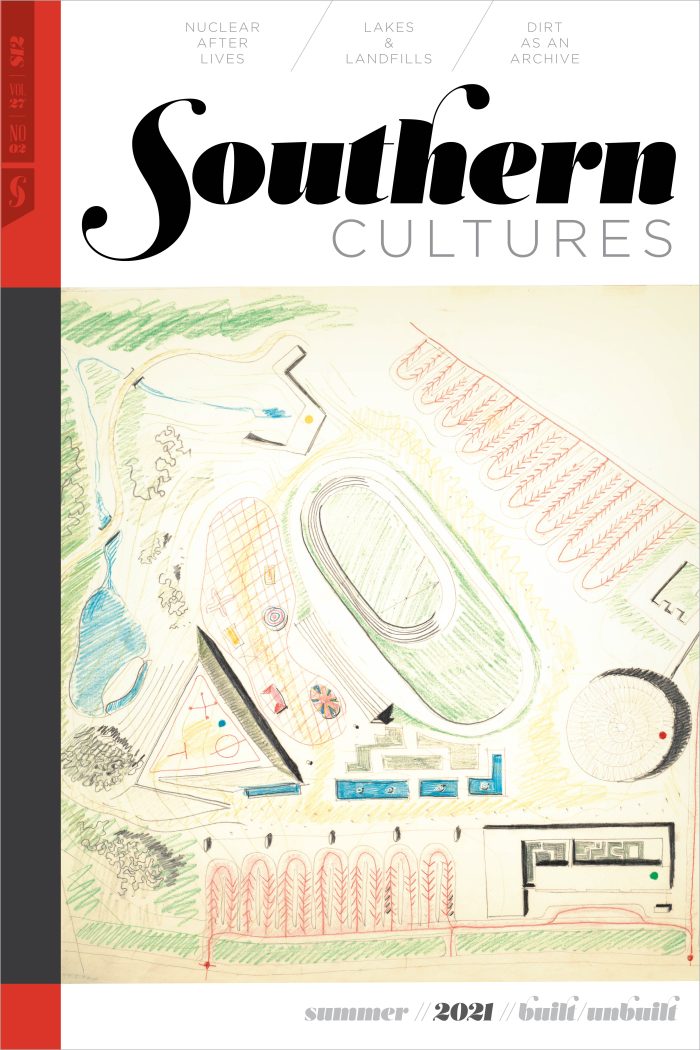

This essay first appeared in the Built/Unbuilt Issue (vol. 27, no. 2: Summer 2021).

CLAIRE RAYMOND is the author of eight books of critical theory examining feminism and race, including The Photographic Uncanny: Photography, Homelessness, and Homesickness (Palgrave, 2019) and The Selfie, Temporality, and Contemporary Photography (Routledge, 2021). She was a faculty member at the University of Virginia for many years and is now a visiting research collaborator at Princeton University.

JACQUELINE TAYLOR is an architectural and art historian working at the intersection of race, gender, and the urban environment. She received her MA and PhD from the University of Virginia, where she also studied historic preservation. She has taught and published widely on modernism and the Black experience.NOTES

- Kevin Risk, “Chalmette Battlefield and Chalmette National Cemetery Cultural Landscape Report,” NPS, 1999; “The Rene Beauregard House,” Historic Resource Study (Chalmette Unit) NPS, 2004.

- Catherine Clinton, The Plantation Mistress: Woman’s World in the Old South (New York: Pantheon, 1982); John Michael Vlach, Back of the Big House: The Architecture of Plantation Slavery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 1–2.

- Carrie Mae Weems, Susan Cahan, and Pamela R. Metzger, Carrie Mae Weems: The Louisiana Project (New Orleans: Newcomb Art Gallery, 2005); Deborah Willis, “Translating Black Power and Beauty: Carrie Mae Weems,” Callaloo 35, no. 4 (Fall 2012): 993–996.

- Lisa Ze Winters, The Mulatta Concubine: Terror, Intimacy, Freedom, and Desire in the Black Transatlantic (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018); Amy R. Sumpter, “Segregation of the Free People of Color and the Construction of Race in Antebellum New Orleans,” Southeastern Geographer 48, no. 1 (May 2008): 19–37.

- Robert S. Brantley, Henry Howard: Louisiana’s Architect (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2015).

- Weems, Caban, and Metzger, Carrie Mae Weems; Justin A. Nystrom, New Orleans after the Civil War: Race, Politics, and a New Birth of Freedom (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010).

- Susan Caban, “Carrie Mae Weems: Reflecting Louisiana,” in Carrie Mae Weems, The Louisiana Project (New Orleans: Newcomb Art Gallery, Tulane University, 2003); Karen Kingsley and Lake Douglas, Bienville Basin Apartments (Iberville Housing Development), Society of Architectural Historians Archipedia, https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/LA-02-OR33.

- Rebecca Solnit, A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster (New York: Penguin, 2010).

- “Art and Activism: A Conversation with Carrie Mae Weems and Khary Lazarre-White at NeueHouse,” The Brotherhood/Sister Sol, July 22, 2020, July 22, 2020, https://brotherhood-sistersol.org/psafrom-carrie-mae-weems/; Sarah Williams Goldhagen, Welcome to Your World: How the Built Environment Shapes Our Lives (New York: HarperCollins, 2017), 92.