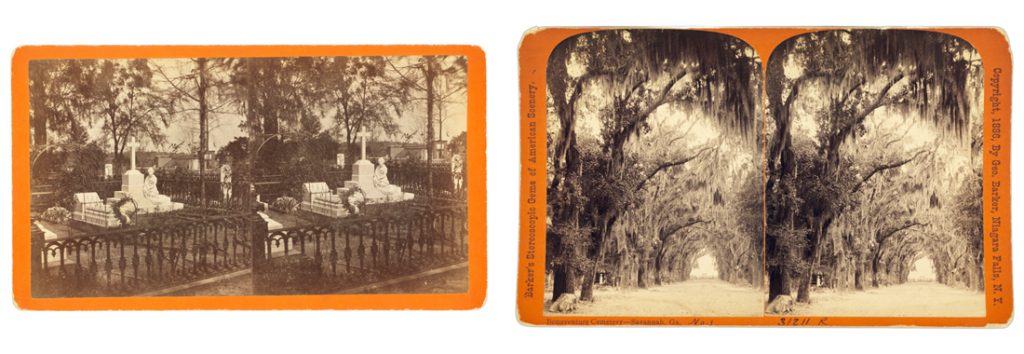

In 1869, twenty-nine-year-old John Muir left his home in Indianapolis and began to walk south. With Florida as his goal, Muir botanized his way through Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Georgia, before stopping in Savannah. There, he ran out of money and had to spend almost a week “camping among the tombs” in Bonaventure Cemetery, a private cemetery just a few miles outside the city. Muir marveled at Bonaventure’s landscape, and declared it “one of the most impressive assemblages of animal and plant creatures I ever met”—high praise from the future founder of the Sierra Club. Although intended for the dead, the cemetery was a living ecosystem replete with Spanish moss, bald eagles, “large flocks of butterflies, [and] all kinds of happy insects,” and he observed that “the few graves are powerless in such a depth of life.” For Muir, Bonaventure showed that humans were only a small part of nature’s cycles of life and death, and he took pleasure in watching the efforts of humans fade into the timeless processes of nature. Where several owners had attempted to ornament their plots with landscaping, Muir noted “how assiduously Nature seeks to remedy these labored art blunders” by “corrod[ing] the iron and marble, and gradually level[ing] the hill,” erasing these human marks on the landscape with “strong evergreen arms laden with fern and tillandsia drapery . . . spread all over.” Muir’s final impression was of Bonaventure as a place where life was “at work everywhere, obliterating all memory of the confusion of man.”

At the time of Muir’s visit, Bonaventure was one of the most popular tourist sites in the nation. Thousands of middle- and upper-class visitors filed through the cemetery’s gates in the mid nineteenth century, and Bonaventure was featured in countless travelogues, poems, short stories, and novels circulated in literary magazines, tourist guidebooks, and newspapers. By the late nineteenth century, the oak-shaded grounds had even attracted notable visitors like Millard Fillmore, Ulysses S. Grant, and William McKinley. Just five years after Muir camped there, Harriet Beecher Stowe—herself one of the cemetery’s many visitors—wrote that “the thing that every stranger in Savannah goes to see, as a matter of course, is Bonaventure.”2

Few tourist sites in the South ever achieved this much fame, especially in the nineteenth century. Yet Bonaventure captivated tourists because it featured a landscape that could not be found in any other rural cemetery in the United States. Even at the beginning of the twentieth century, unpaved walkways meandered through overgrown avenues of live oaks draped with Spanish moss, surrounded on each side by dense foliage. Because cemetery officials were often stymied in their efforts to “improve” the grounds, nineteenth-century visitors watched as vegetation swallowed up ruins, tombs, plots, and avenues. This set it apart from the manicured pastoral scenery of popular rural cemeteries like Mount Auburn in Boston and Laurel Hill in Philadelphia, and it softened the edges between nature and human artifice in a way that few other tourist sites could. While it may seem counterintuitive to view a cemetery as “wild” terrain, nineteenth-century visitors concluded that despite human designs, nature reigned supreme at Bonaventure.3

Even at the beginning of the twentieth century, unpaved walkways meandered through overgrown avenues of live oaks draped with Spanish moss, surrounded on each side by dense foliage.

Bonaventure’s landscape appealed to tourists, but allowing nature to reclaim expensive tombs and monuments was difficult to justify to plot owners, who joined with municipal officials to express a different vision for the cemetery. Rather than maintaining the natural elements that drew tourists, these groups wanted to remake Bonaventure into a pastoral space more reminiscent of mainstream rural cemeteries. For more than six decades, these competing uses of the landscape were in tension. Was Bonaventure a tourist site or was it working cemetery? The changing ways that businesspeople, city residents, public officials, and tourists answered this question had important implications for the complex history of this celebrated site. Their efforts to define the landscape also shed light on broad shifts in how southerners viewed their natural environment and the best paths for economic development.

Historians have written a great deal about the nation’s rural cemeteries, which played key roles in the evolution of American landscape design and shaped popular ideas about nature well into the twentieth century. Yet Bonaventure suggests that rural cemeteries could be more than just “middle landscapes” designed to strike a balance between the wilderness and the city. Scholars focus almost exclusively on northeastern cemeteries, but the history of Bonaventure also helps to write the South back into this important movement. Indeed, physical changes to Bonaventure’s landscape and different ways of imagining the cemetery’s function can reveal a lot about the unique southern experience with rural cemeteries, which were not always popular for the same reasons as in other places. Even if they wanted to mirror the popular manicured landscape of Mount Auburn, southern cemetery officials had to contend with natural, ideological, and political forces specific to their region that often thwarted their hopes of recreating pastoral landscapes.4

Right: Bonaventure Cemetery, Savannah, Georgia, Detroit Photographic Co., 1901, courtesy the Library of Congress.

Even today, Bonaventure is one of the South’s most iconic places.

Conflicts over the future of Bonaventure also suggest how tourism placed southern boosters in a bind. By the twentieth century, tourism was a profitable big business, but early sites often prioritized aesthetic or “romanticized” uses of nature that clashed with other developmental priorities. Wild landscapes may have been good for nineteenth-century tourism, but in Savannah, as elsewhere, they were frequently deemed to be incompatible with pressing economic or public health concerns. Struggles over the landscape of Bonaventure sheds light on how southern boosters worked to balance tourism and other civic needs, and how they navigated these conflicting developmental paths—in the process reshaping southern landscapes.5

Even today, Bonaventure is one of the South’s most iconic places. Yet this label has obscured the complex changes to its landscape over two centuries. Writing Bonaventure’s oaks and tillandsia back into historical narratives can tell us a lot about the evolution of tourism in the South, how memories of the past are intertwined with the landscape, and it can make us more aware of our own assumptions about what is “wild.”

Conflicts over the future of Bonaventure also suggest how tourism placed southern boosters in a bind. By the twentieth century, tourism was a profitable big business, but early sites often prioritized aesthetic or “romanticized” uses of nature that clashed with other developmental priorities. Wild landscapes may have been good for nineteenth-century tourism, but in Savannah, as elsewhere, they were frequently deemed to be incompatible with pressing economic or public health concerns. Struggles over the landscape of Bonaventure sheds light on how southern boosters worked to balance tourism and other civic needs, and how they navigated these conflicting developmental paths—in the process reshaping southern landscapes.5

Even today, Bonaventure is one of the South’s most iconic places. Yet this label has obscured the complex changes to its landscape over two centuries. Writing Bonaventure’s oaks and tillandsia back into historical narratives can tell us a lot about the evolution of tourism in the South, how memories of the past are intertwined with the landscape, and it can make us more aware of our own assumptions about what is “wild.”

Read the full essay in the Summer 2017 issue (vol. 23, no. 2).

William D. Bryan is an environmental historian, and he teaches at Georgia State University. He is completing his first book, The Price of Permanence: Nature and Business in the New South (forthcoming, University of Georgia Press), which explores how nature conservation shaped the American South after the Civil War.